INSECTS AND ARACHNIDS

Insects and arachnids are both arthropods or “jointed-leg” animals. Other arthropods include crabs, shrimps, millipedes, centipedes, and the extinct trilobites. Arthropods make up about 85 percent of all animal life in terms of number of different species. The class Insecta makes up 90 percent of all arthropods. This includes earwigs, bedbugs, spittlebugs, and boll weevils, along with beetles and butterflies, to name just a few of the more than 100,000 insect species in the United States.

The smaller group, class Arachnida, which includes spiders, ticks, mites, harvestmen, and scorpions, is characterized by animals with eight legs and two body regions, the abdomen and the cephalothorax, and no antennae. They grow by molting their exoskeleton. They were one of the first groups of animals to colonize land roughly 400 million years ago. Most species are terrestrial.

Insects have six legs, three distinct body regions (a moveable head, a rigid thorax, and a flexible abdomen), a pair of antennae, and, in most species, two pairs of wings. All insects go through a metamorphosis from egg to adult. The grasshoppers, true bugs, and lice, to name a few, have a nymph stage between egg and adult. The nymph looks similar to an adult but is sexually immature and usually lacks wings. They grow by molting their exoskeleton. With each molt the wing pads increase in size. Dragonfly, mayfly, and stonefly nymphs, however, differ from adults more than most other insects that mature through this process, which is known as “simple” metamorphosis.

About 80 percent of all insect species develop through complex or complete metamorphosis. Their four-stage life consists of egg; larva or grub, when they are active and feeding and look nothing like the adult; pupa, when they are encased in a mummy-like cocoon or chrysalis; and adult, when the wings unfold. Caterpillars are the larval stage of butterflies and moths, while maggots eventually become flies, and grubs metamorphose into beetles.

Canyon country insects and arachnids range in size from microscopic mites to 5-inch-long scorpions. They live from several days to 15 to 20 years. They live underwater; underground; and in plants, burrows, and nests. While a few damage crops and bother animals, including humans, most are beneficial. Bees and other flower-visiting insects are essential for pollination of many plants. In addition, little decomposition would occur without insects.

Despite some people’s perception that a vast bug conspiracy exists, no insect or arachnid is waiting for a tasty human to come along. They evolved long before humans. The best defense is rather simple; leave them alone and they will leave you alone. You can help yourself by not putting your fingers in cracks or prodding webs or nests, by checking your shoes before putting them on if you left them outside at night, and by remaining calm if you encounter one.

In regard to venom and poison: These terms have different meanings. Venom must be injected via fangs, spurs, spines, or harpoons. Poison, in contrast, is absorbed or ingested; you must touch or eat the animal or plant to feel the effects of the toxin.

If you are stung or bitten, however, do not panic. Try to positively identify your assailant. If it was a wasp, bee, black widow spider, or scorpion, or if you develop allergic reactions, go to a hospital. Otherwise most bites are more painful than life threatening. If you are unsure or uncomfortable, seek professional help.

This section describes a few of the colorful, common, or controversial insects and arachnids found in the Southwest.

Butterflies and a Moth

Beloved yet often overlooked, butterflies are one of the few types of insects that people universally seem to like. They are beautiful, do not bite or sting, and are graceful in flight. They are also diverse and abundant with around 200 species in Utah and more than 330 in Arizona. Butterflies can be found throughout canyon country from riparian zones to open desert to mountaintops. They are one small part of the order of insects known as Lepidoptera, or “scaly wing.” These scales, or modified hairs, are what give lepidopterans color, either through pigments or by reflecting color.

Moths make up the much larger part of the order, outnumbering butterflies at least fifteen to one. They are easy to tell apart. Butterflies have clubbed antennae, fly strictly during the day, and are brightly colored. Moths usually fly at night, lack clubbed antennae, and are typically drab in color. They also tend not to hold their wings vertically over their bodies.

Both pass through a complete metamorphosis from egg to larvae to pupae to adult. Eggs are typically less than a millimeter wide but if looked at under a magnifying lens reveal a complicated architecture. They are generally laid singly on a host plant, which the larvae, or caterpillar, can consume. Larvae have two goals: eat and don’t get eaten. During the several weeks of life as a caterpillar, they can grow a hundredfold in size, passing through several molts, known as instars. To protect themselves, many larvae have hairs that can be painful to birds, and even to humans.

After reaching its full size, the caterpillar will use silk to secure itself in a secluded spot where it forms the pupa. As a pupa, it is essentially dormant and has little to no interaction with its surroundings. Unfortunately, there is no easy way to distinguish butterfly and moth caterpillars and pupae from each other.

This cycle of life takes weeks to years to accomplish. Butterflies can enter into a state called diapause, where they basically turn off all life functions. They can diapause as eggs, larvae, pupae, or adults. This phase is weather dependent. Most butterflies, though, live less than a year and spend only a few weeks as an adult. Names and use of capitalization of common names conforms with A Catalogue of the Butterflies of the United States and Canada by Jonathan Pelham.

TWO-TAILED SWALLOWTAIL

Papilio multicaudata

Papilionidae family

Wingspan 3.5–4.5 in.

One of a number of large yellow butterflies, the Two-Tailed is the biggest in the region and characterized by the twin tails on each hind wing. Other swallowtails include the Anise (P. zelicaon) and Western Tiger (P. rutulus), both predominately yellow, and the Indra (P. indra) and Black (P. polyxenes), both black. Two-Taileds are canyon denizens, where their strong and active flight grabs one’s attention. When you do see one, it is probably a male out in search of a female. Also look for them nectaring at damp spots.

Larvae are Granny-Smith-apple green with yellow eye spots rimmed in black. This fake face may help deter predators. Caterpillars can further discourage attackers by everting an orange prong, or horn, from behind their head, which emits a citrus smell.

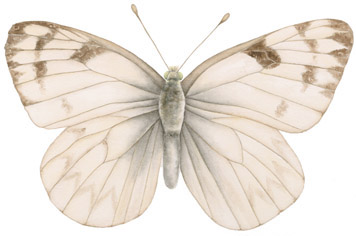

BECKER’S WHITE

Pontia beckeri

Pieridae family

Wingspan less than 2 in.

Lepidopterists understand naming animals. Those with the name white have white wings, those with sulphur in their name are yellow, and those with blue have blue wings. There are even a couple called commas because of the white punctuation mark on their wings. Of course distinguishing these bugs down to species level can be taxing, but at least you often have a head start.

The moss green venation coloring on the ventral wings of these medium-size flyers is not technically green but consists of black and yellow scales. One study found that Becker’s Whites fluoresce under UV light, which may aid in species recognition. They produce multiple broods during their summer flight season. Mustards are the preferred host plants.

Ludwig Becker was a German naturalist who died on an expedition in Australia.

CABBAGE WHITE

Pieris rapae

Pieridae family

Wingspan less than 2 in.

One of most common butterflies of the urban environment, Cabbage Whites are native to Europe. Called “ravenous and destructive,” they were first collected in Quebec in 1860 and quickly spread across the entire continent. The main concern was that they outcompeted native species of Pieris and that they ate crops such as cabbages. They also eat kale, broccoli, and Brussels sprouts.

Cabbage Whites fly year-round and can produce multiple broods across several seasons. Their wing tips look to be dipped in ink, which then left dots on the dorsal forewing, two on females and one on males. The ventral surfaces are light yellow.

CHECKERED WHITE

Pontia protodice

Pieridae family

Wingspan less than 2 in.

A resident species of warmer climates and one able to fly during the hotter parts of the day, Checkered Whites inhabit open areas, often in disturbed habitat. They, and other white butterflies, have evolved a novel thermoregulatory posture called reflectance basking, in which the wings act as solar reflectors bouncing heat to the butterfly’s body. This helps provide enough warmth to allow flight.

Like other whites, their larval food plants are predominately mustards, including domestic and native, such as tansy mustard and pepperweed. The scientific name protodice comes from the Latin for “first season” in reference to their early season appearance. The closely related and very similar-looking Western Whites (P. occidentalis) may also be seen in canyon country.

ORANGE SULPHUR

Colias eurytheme

Pieridae family

Wingspan less than 2 in.

Lepidopterist and writer Bob Pyle says that another member of this genus, the Pale Clouded Sulfur, “is the best candidate for the Original Butterfly: a ubiquitous, butter-colored European insect much like this one that suggested the name butterfloege in Old English.” The sulphurs are indeed butter hued and extremely hard to tell apart without a careful inspection, though the Orange Sulphur is distinctly more orange than other species.

Also known as alfalfa sulphur, they can form dense swarms on alfalfa, clover, and locoweeds. Like other sulphurs, they fold their wings over their backs when they land so seeing one with wings spread is a rare sight. They have been known to hybridize with Eriphyle’s Sulphurs (C. eriphyle), though the Orange’s ability to fluoresce in UV light generally helps females distinguish their true mates.

PAINTED LADY

Vanessa cardui

Nymphalidae family

Wingspan less than 3 in.

A truly cosmopolitan species, found on all the continents except Antarctica, Painted Ladies have a wider distribution than any other butterfly. They are one of three species of lady butterflies that have colorful and similar markings and that occur in the region. The others are the American Lady (V. virginiensis) and the West Coast Lady (V. annabella). The name “lady” comes from an early name for the species, belladonna, or “pretty lady.”

Painted Ladies are an irruptive species, meaning they can appear by the millions in certain years. All of these are migrants coming out of the south as they do not overwinter in colder climates. When they arrive, they can cover rabbitbrush and thistle in great patches of salmon and blotchy brown and white beauty. Look for them hilltopping or around taller trees, catching the late evening sun. They occur in all habitats throughout canyon country.

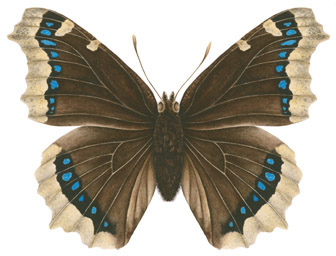

MOURNING CLOAK

Nymphalis antiopa

Nymphalidae family

Wingspan more than 3 in.

Big and beautiful, Mourning Cloaks are one of the easiest butterflies to recognize. No other species looks like it and it is the only native species that may be seen year-round. They are velvety black with a yellow border, which fades to white over time. Unlike most butterflies, Mourning Cloaks can overwinter as adults.

Look for them nectaring on the sap of poplars or on fruit trees in orchards. They also have a very conspicuous caterpillar, black with a row of orange spots on their back, as well as black spines. Large groupings of larvae on willows or cottonwoods are common.

WEIDEMEYER’S ADMIRAL

Limenitis weidemeyerii

Nymphalidae family

Wingspan less than 3½ in.

Often found in the mountains of canyon country, Weidemeyer’s Admirals also occur along streams and in open woodlands. At rest, their black wings with one continuous line of white form a stark contrast to most any place they stop. The common name may refer to this singular band, which suggests a military stripe of rank, or it may allude to the male’s propensity to have a favorite perch from which he defends his territory. Some compare this to an admiral defending a harbor.

Larvae overwinter in a hibernaculum, which they form by wrapping themselves in a leaf and silk. They emerge in spring to become adults. Look for them on aspen or willows. They may also be found sipping mud, or other less tasteful items, such as dung. They are probably in search of sodium.

John William Weidemeyer made the first official collection of this species in the middle 1800s.

VARIEGATED FRITILLARY

Euptoieta claudia

Nymphalidae family

Wingspan less than 2½ in.

One of many fritillary butterflies, most of which present challenges to distinguish, the Variegated has a wide habitat tolerance from urban to desert to mountain. They have the characteristic pattern of yellowish to orange wings above peppered with black bars and dots. This is the only species in the genus in the area; most others are classified as Speyeria, the greater fritillaries, and characterized by being larger and having silvery metallic spots below. Variegateds do not overwinter in areas of hard frost so often are migrants into this region and certainly farther north. Look for them and other frits wherever violets grow.

The Nymphalidae, or brush-foot family, gets its name from the front two legs, which are about half the size of the back four. In addition, hairs cover the legs so that they look like wee brushes. Bob Pyle writes that “lepidopterists know the brush-foots as ‘smart’ butterflies—perceptive, highly responsive, agile, and adaptable.”

SATYR ANGLEWING

Polygonia satyrus

Nymphalidae family

Wingspan less than 2¼ in.

This is a butterfly of great contrast with golden orange and black splotched upper wings and muted undersides that look like bark. The common name “anglewing” describes the wings, which look almost as if someone has taken bites out of them. “Satyr” refers to their preference for forested environments, though they are more often found along riparian areas. Another common name, “comma,” alludes to a small, white crescent on the underside. Satyr Anglewings are the most common desert member of this genus. Look for them in areas of nettles, but when they land, they may disappear into the background.

JUBA SKIPPER

Hesperia juba

Hesperidae family

Wingspan less than 1¼ in.

The common name for this very large group of butterflies comes from their skipping flight pattern, as if they are bouncing along through the air. Skippers are generally dull colored, with short, often hooked or curved antennae, and somewhat triangular wings. Most are small, and most cannot hold their wings completely spread out. When they land, the forewings stick up at 45 degrees to their body.

The tiny caterpillars are often found on bunchgrasses such as ricegrass and needle-and-thread, where they make nests of rolled plant and silk. Adults feed on nectar on rabbitbrush and are strongly territorial, at least the males are.

The Juba Skipper name appears to be a corruption of the name of the area where they were first collected, near California’s Yuba River.

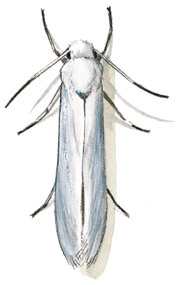

YUCCA MOTH

Tegeticula altiplanella

Prodoxidae family

Wingspan about an inch

Illustration © Todd Telander

Yucca Moths are nifty examples of the beauty of evolution. The females have specially adapted tentacles that allow them to collect the sticky pollen grains of yuccas, which they then fashion into a compact ball and store under their head. The female then flies to another yucca plant and deposits a single egg into the flower’s ovary. Before flying away, she uses her tentacles again, removes a small quantity of pollen, and deposits it on the plant’s stigma. A week or so later, the moth’s eggs hatch and the larvae begin to feed on the seeds maturing in the ovary but not on all of them, thus allowing the plant to benefit, too. Larvae overwinter in silken, subterranean cocoons. No other species pollinate yuccas.

Long thought to be a single species, the Yucca Moth, Tegeticula yuccasella, was recently reclassified into more than a dozen distinct species. Curiously, two don’t pollinate; they are cheater species that simply deposit eggs.

All varieties are white with dark bodies. They rest in the flowers during the day and become active shortly after sunset. Attracted to UV light, they remain mobile for 2 to 4 hours after dark.

Dragonflies and Damselflies

Masters of flight, dragonflies can fly forward and backward, at speeds up to 60 mph. They hover. They nab prey in flight and mate in flight, even escaping from predators while so engaged. Dragonflies are some of the most conspicuous insects in canyon country, active during the day, rarely very far from water.

Dragonflies and damselflies are members of the order Odonata, or “toothed jaw.” They first evolved their four flight wings around 300 million years ago and have remained little changed in the past 200 million years. (The largest dragonflies lived 280 million years ago and had a 29-inch wingspan.) Of the two groups, damselflies have thinner abdomens, a hammer head with eyes wide apart, and hold their wings parallel to their abdomen. Both have colorful bodies and often colorful eyes.

With their excellent flight skills, odonates are also first-rate predators, either sallying forth from a perch to nab a meal or chasing down prey, a practice known as hawking. Hawking dragonflies can often form large groups, flying precise paths. They catch insects and other dragonflies with their legs, which form a scoop.

Larvae are also fierce predators, consuming insects, small fish, and tadpoles. They remain as larvae for a few weeks to a few years. An adult’s life span is generally 5 weeks though some live for 10 weeks.

Perhaps their most infamous skill is mating. There is little polite about it with males swooping in and pouncing on females, sometimes going so far as to knock them to the ground. Males may also inadvertenly attempt to mate with females of a different species. Once he has successfully found the right partner, he uses specially modified parts on the end of his abdomen to grasp the female behind the neck. Once linked he transfers sperm to secondary genitalia under the forward end of his abdomen. She then extends her abdomen under his to receive the sperm.

Known as a wheel, this sexual position is unique in the insect world. While in tandem, they often remain in flight, during which the male typically spends most of his time removing another male’s sperm before depositing his package. Names and use of capitalization of common names conforms with North American Odonata, produced by the Dragonfly Society of the Americas.

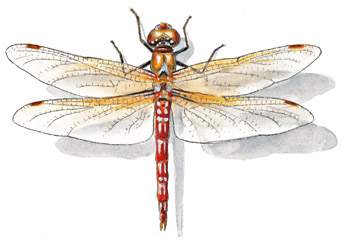

VARIEGATED MEADOWHAWK

Sympetrum corruptum

Libellulidae family

Length 4–4½ in., wingspan 2½–3 in.

Illustration © Todd Telander

As the name implies, this species has a wide range of coloring, from gray to light pink to gold. The key identifying feature is a row of white-rimmed black dots running down the side of the abdomen. Also, look for two diagonal stripes that end in a yellow dot on the thorax. They have a tan to ivory face with light brown eyes.

Variegated Meadowhawks both sally and hawk after insects. They tend to sally out from ground-level perches, often from grass stems, and hawk over ponds. Look for them along slow-moving streams and near ponds. Like several other species in the genus, S. corruptum migrate and can sometimes be found in large numbers during this movement. No one knows the origin of the specific epithet corruptum.

TWELVE-SPOTTED SKIMMER

Libellula pulchella

Libellulidae family

Length 2 in., wingspan 3½ in.

These are easily distinguished by the three black spots found at the leading edge of each wing. Other skimmers have four total spots (L. quadrimaculta) and eight spots (L. forensis). Twelve Spots have a brown body, whitish spots between the black spots, and a yellow-brown face.

Inhabiting open ponds and streams with good sunlight, this is an aggressive species, with males actively defending their territories from other dragonflies and other intruders. They tend to perch higher up in vegetation. Unlike some species, the females will oviposit after breaking out of the wheel mating position. The generic name comes from the Latin for “little book,” in reference to how the open wings are spread. Pulchella means “pretty little one.”

BLUE-EYED DARNER

Rhionaeschna multicolor

Aescnidae family

Length 2½–3 in., wingspan 3½–4 in.

Illustration © Todd Telander

Common and colorful, these are some of the most conspicuous dragonflies of canyon country. They have a classic dragonfly flight pattern of hovering and rapid changing of direction, usually just a few feet above water, though females may forage away from water.

With their pale blue face and bright blue eyes, the males are one of the most beautiful bugs. Females tend to be more drab and can have a multicolored pattern.

The common name darner alludes to a notion that dragonflies could sew your eyes shut, which also led to the folk name “devil’s needle.” Another false belief is that dragonflies have a venomous sting. They cannot sting, and neither larvae nor adults can inflict much of a bite.

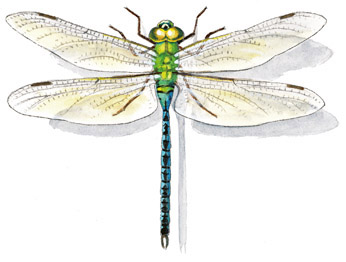

COMMON GREEN DARNER

Anax junius

Aescnidae family

Length 2½–3 in., wingspan 3½–4 in.

Illustration © Todd Telander

A slightly misleading common name as these insects are green only on the thorax; the face is yellow-green and the abdomen sky blue. The closely related A. walsinghami is the largest North American dragonfly. The scientific name Anax refers to the great size of these species. It means “lord” or “master.”

Green Darners are a migratory species, moving out of the south and arriving in spring, often before other species arrive. In Russia, this arrival is reflected in their common name “scout.” There are also resident populations where the larvae overwinter. Look for Green Darners over ponds and in evening swarms.

Males are notorious for their belligerent behavior against other males mating with females. High-speed film footage shows males “ramming, pulling, and biting the escorting male, who tries to defend himself by beating his wings, clinging to plants, vibrating his body in sudden spasms, and biting his attacker in return.”

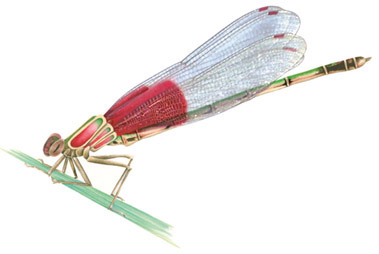

AMERICAN RUBYSPOT

Hetaerina americana

Calopterygidae family

Length 1½ in., wingspan 2½ in.

Part of a genus found primarily in the neo-tropics, American Rubyspots are a typical damselfly with their narrow body and habit of holding their wings directly over their bodies, as opposed to spreading them out like dragonflies. (One group of damselflies, the spreadwings, however, contradicts this general rule. The Great Spreadwing [Archilestes grandis] occurs in canyon country. They can be distinguished from dragonflies by the slender abdomen and yellow line on the thorax.) Other common damselflies are bluets, with their brilliant blue and black bodies.

American Rubyspots look a bit like Christmas time with an iridescent green body and red head and thorax, complemented by the red wing spots. Females have an unusual capacity to oviposit while completely submerged. One study found they can remain underwater for up to an hour, with a male patrolling above her and chasing away potential mates.

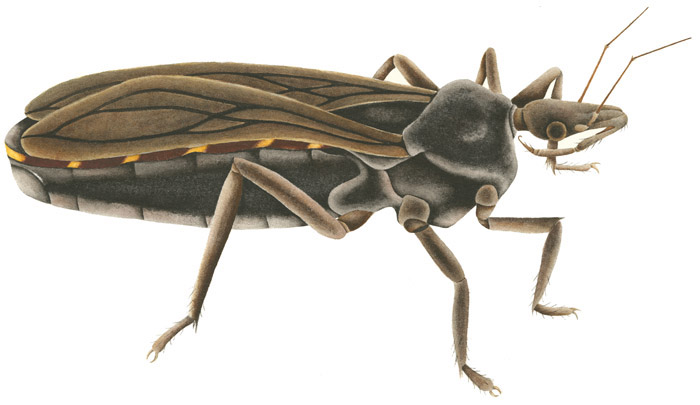

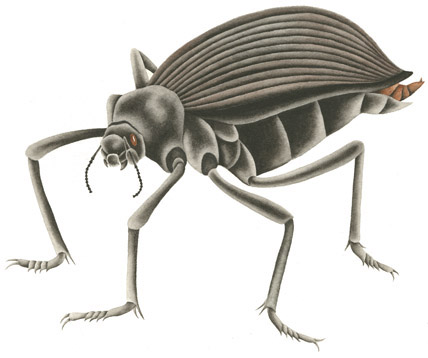

CONE-NOSED KISSING BUG

Triatoma sp.

Reduviidae family

½–1 in., black with elongated cone-shaped head

Commonly known as assassin bugs, Walpai tigers, and kissing bugs, these 1-inch-long bugs are bloodsuckers. They usually live in wood-rat nests, where they have a ready source of blood, but the adults are attracted to light and often end up inside people’s homes. They spend the day out of sight in cracks and crevices and then emerge at night to seek a blood meal. The kissing bug’s common name comes from its propensity to suck blood from a person’s exposed face or neck.

The bite generally forms a large welt (up to 3 inches wide) and can cause swelling or a systemic reaction. A severe reaction leads to anaphylaxis. In South and Central America, Triatoma carry Chagas disease, which affects the nervous system and heart and can be deadly if left untreated. (Many people have speculated that Charles Darwin contacted Chagas disease when he was in Chile. He was bitten by a Triatoma bug, but without exhuming his body there is no way to know if he had the disease.) The disease is spread when the victim rubs the insect’s fecal material, which carries the parasite, into the wound, eye, nose, or mouth. If you are bitten, wash well around the bite and do not smash the insect on your body.

VELVET ANT

Dasymutilla sp.

Mutillidae family

½–1 in. long, females wingless, densely covered with orange, red, yellow, or black hairs

Most of us have been warned not to judge a book by its cover. You should not judge insects that way either. Velvet ants look like hairy, extravagantly colored ants, which might be fun to pick up. Do not be fooled. They are actually wasps that have a particularly painful sting; one common name is “cow-killer.” The orange, yellow, or red wingless females, which are encountered more often than the winged males, are often seen scurrying across the ground.

Velvet ants are active during the day and may be some of the first to hit the trail and last to settle in for the night. They retreat midday by burrowing under debris or climbing into plants. Nectar is the preferred food. If you see a walking velvet ant, you can be assured that it is a female, which is probably searching for other ground-nesting wasps or bees on which to deposit their eggs. When they hatch, the larvae will consume their hosts before pupating into adults.

Over 150 species of velvet ants occur throughout North America, although this is a rough number. Three commonly seen species in this region should be Dasymutilla bioculata (also reddish), D. vestita (red to orange), and Pseudomethoca propinqua (golden). The latter two parasitize bees and are more common on harder packed soil, versus D. bioculta, which prefers sand wasps and open sandy areas. There are probably around ten more diurnal species and about thirty nocturnal species.

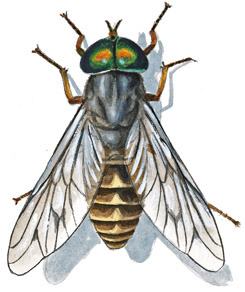

HORSE FLY

Tabanus sp.

Tabanidae family

Up to 1 in. long, bodies black, eyes often with green stripes, wings clear, antennae short

Illustration © Todd Telander

The bigger and faster cousin of deer flies, horse flies inflict a painful bite. Larvae, which can be up to 2 inches long, can bite as well. They are also cannibalistic, which may aid humans by reducing the density of individuals.

To aid in their phlebotomous ways, horse flies secrete an anticoagulant into the wound. This prevents clotting and enables them to slurp up to 200 mg of blood in 1 to 3 minutes. They require approximately ten visits to complete one blood meal. Researchers have begun to study the anticoagulant for potential human uses.

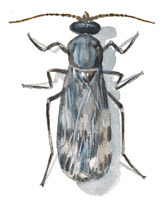

DEER FLY

Chrysops sp. (over 75 species in North America)

Tabanidae family

½ inch long, a common species, C. discalis, has pale yellow and black markings with darkish patches

Illustration © Todd Telander

A notorious biter, and a relatively slow flier, deer flies are an ironically easy pest to swat. Of course, your satisfying kill occurs because the fly, always a female, has taken a nice nip out of you. She does so not by puncturing your skin as a mosquito does but by using her scissorlike mouthparts to cut into you, which facilitates her sucking up the flowing blood. Males cannot bite; they feed on nectar.

Deer flies are about the size of a house fly. After overwintering in wet soil near ponds and streams as larvae, adults emerge in spring and fly through the summer. They are visual bugs, attracted to dark, moving objects, and to carbon dioxide. Warm, low-wind, sunny days are when they are most active, primarily attacking the head, neck, and shoulders. If the situation is dire, some people have turned to various patches and traps, many of which are bright blue and coated in sticky material that prevents flies from escaping.

Deer flies are a principal vector of Francisella tularensis, the bacteria that causes tularemia. The disease, which had an outbreak in Utah in 2007, produces chills, fever, muscle pain, and joint stiffness. Because deer flies can feed on multiple hosts, they can trigger acute outbreaks of tularemia. Tularemia seldom kills but is not pleasant.

BITING MIDGE

Culicoides sp. and Leptoconops sp.

Ceratopogndae family

Less than ¼ inch long

Illustration © Todd Telander

Gnats, no-see-ums, punkies, #*@$ bugs. We know these voracious little biters by many names. Entomologists prefer biting midges, particularly for the main genus, Culicoides, found in southern Utah. More than a dozen genera with over 100 species live throughout the region. All of them require water in some form during the larval stage. Water may be on vegetation, in pools, in wet soil, or springs, to name a few locales.

Most Culicoides are crepuscular or nocturnal feeders but will come out on overcast and/or calm days. Leptoconops, in contrast, come out and bite during the day. Only a handful of experts can tell the different species apart.

While many of us may hate biting midges, we should rejoice that our most common local varieties do not transmit disease. Plus, the most important pollinators of cacao are biting midges. As with all biting midges, only the males are the pollinators; females are the bloodsuckers. And if that doesn’t excite you, one species has the fastest recorded wing beat of any insect, at 1,046 beats per second, and another has been found in 120-million-year-old Lebanese amber. In addition to biting humans, midges attack all varieties of animals from caterpillars to birds.

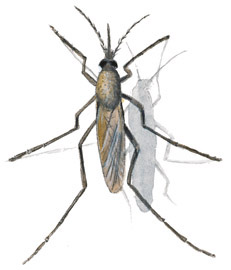

MOSQUITO

Fifty species in the state, including many in the genera Culex, Ochlerotatus, Aëdes, and Anopheles

Culicidae family

Larvae, up to ½ inch long; adults ⅛ to ⅓ in. long, brown to dark brown

Illustration © Todd Telander

Mosquitoes exemplify one of the pleasures of teasing out the meaning of scientific names. Consider two of the genera found in canyon country. Anopheles is the Greek word for “troublesome” and Aëdes is their word for “disagreeable,” two of the best descriptors of mosquitoes. Add to these specific names such as excrucians (tormenting), provocans (provoking), and vexans (annoying) and you can understand that those who study and name mosquitoes recognize the bugs’ aggravating lifestyle. The name of Culex pipiens, or the common house mosquito, comes from the Roman term for piping, in reference to their whining flight.

Mosquitoes have two basic life plans. Some have short lives dependent upon temporary water from rain or flooding. They are typically diurnal and deposit eggs in soil that might not be wet for some time. Some produce a single brood and some as many as ten generations of biters. One species, Aedes vexans, is notorious for their huge, post-flooding numbers. Fortunately, they do not survive long in hot, dry weather.

Other mosquitoes rely on permanent or semi-permanent water sources. These species often hibernate in buildings or under bridges. They become active after sunset and can remain active till dawn. Culex species of mosquito that have this habit are known vectors of West Nile virus and Western and St. Louis encephalitis. They are aggressive biters, though C. pipiens typically favor birds over humans.

The eggs hatch in the water, becoming wiggling larvae. They breathe through a siphon-like tube near their rear ends. After a week or so of feeding, they develop into a nonfeeding pupal stage, characterized by a tumbling movement through the water.

Once out of the water and flying as adults, mosquitoes begin to torment animals. The goal, at least for females, is to acquire sustenance for their eggs. They do this by injecting their proboscis into our skins and sucking our blood. To aid in finding blood, they pump saliva into our bodies. Males do not bite but do have another singular goal; they hang out near us and our warm, carbon dioxide-spewing bodies with the hope of finding a mate. They do so by using their “bottlebrush” antennae to home in on the pitch of her wingbeats. Post-mating, she goes in search of us for our protein-rich blood, and he usually dies.

When not mating or trying to mate, both females and males visit flowers to steal pollen. They are known to pollinate only a few plants including the orchid Platanthera obtusata, which grows in northern Utah.

On a positive note, mosquito larvae and adults feed many animals including bats, birds, dragonflies, tadpoles, and fish. And finally, some claim that the town name Moab is a corruption of a Paiute word—moapa—for mosquito, in reference to the mosquito-rich areas along the Colorado River.

DARKLING BEETLE

Eleodes sp.

Tenebrionidae family

1 in., black

Beetles in the genus Eleodes are known as darkling or pinacate beetles, and colloquially as stinkbugs or clown beetles. Pinacate comes from the Aztec pinacatl, for “black beetle.” Darkling is a common name applied to several genera and over 1,400 species within the family Tenebrionidae. Eleodes, derived from the Greek term for “olivelike” describes the general body shape and jet-black coloration.

More than 120 species are in the genus in the western United States occurring across ecosystems from open dunes to shrubs to mountains. Many are about 1 inch long, and all eat dead plant material and fungi. None are venomous, although a few varieties can spray a noxious liquid from the end of their abdomen. This leads to their typical defensive pose of head down and rear end pointing up. Most would-be predators leave the darkling beetle alone when threatened with this fearsome stance, but grasshopper mice simply grab the beetle, jam its behind into the sand, and eat the front end. You occasionally find these half-eaten beetles in sandy areas.

Pinacate beetles are one of the great walkers of the beetle world and can be encountered throughout the year. From spring to autumn they are crepuscular and nocturnal, but come fall they revert to a more diurnal lifestyle. Studies have shown that they are probably in search of food, which they can find by odor.

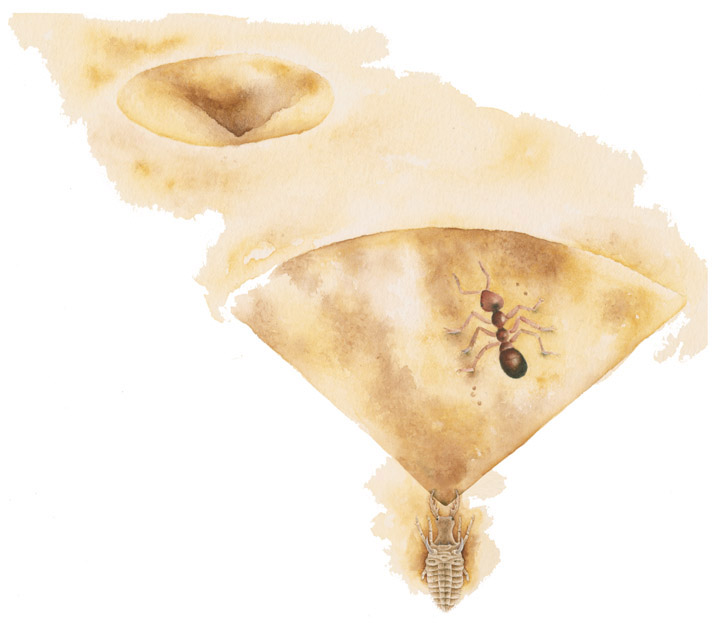

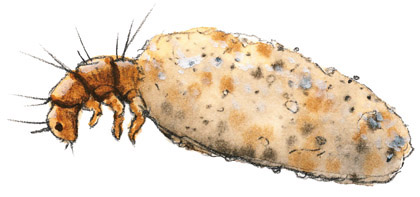

ANTLION

Myrmeleon sp.

Myrmeleontidae family

Larva, ½ in. long, wide abdomen with long, curved jaws; adult, 1½ in., slender wings

Antlions are rarely seen, but their homes are extremely common. The larvae construct conical pits to trap ants. When an ant crawls or stumbles into the pit, it creates an avalanche of sand, sending the victim to its death, for the antlion larva lurks underground at the nadir of the pit. When the ant hits bottom, the larva uses its elongate jaws to grab the ant and pull it underground. Antlions kill their prey by injecting a paralyzing venom and then sucking out the contents of its body. The carcass is then flicked out of the pit.

Antlions are also known as doodle-bugs, because of the path they make when moving to a new burrow. Burrows are made by backing around in ever-tighter circles, pushing out dirt with their jaws.

Except for their clublike antennae, adult antlions resemble drab damselflies. They eat little or nothing at all, are poor fliers, and are active only at night. The goal of their 1-month adult life is reproduction.

CADDISFLY

More than 10,000 described species worldwide

Hydrotilidae family

³/₁₆–1½ in. long larval cases covered in debris; adults ¹/₁₀–¹/₅ in. long of common species

Illustration © Todd Telander

Entomologist Glenn Wiggins has written “caddisflies are remarkable animals close at hand, to be seen and appreciated by any who are interested in the ways the world works.” Few bug larvae build such elaborate homes. Made of plant debris and bits of rock held together by silk secreted from its mouth, the tubular enclosures not only protect the larvae but also have a hydrologic function, altering the flow of water to the benefit of the inhabitant. The enclosures, or cases, may be permanent or toted around by the caterpillar-like larvae. The portable case makers use bits of debris and will add material at one end and trim the other. Permanent cases are usually attached to rocks and can be a variety of shapes from tubes to funnels to cocoonlike. Some are also constructed as a net in cracks or between rocks and catch floating plant and animal debris. Larvae and adults are an important food source for fish, particularly for trout. Adults look a bit like moths and are mostly nocturnal.

One study in the Grand Canyon found that the most abundant caddisflies were in the family Hydroptilidae, or microcaddisflies. The adults are no more than ¹/₁₀ to ¹/₅ inch long. The larvae make what are known as purse cases, which resemble domes. Genera include Ochrotrichia, Hydroptila, and Oxyethira.

There is some confusion over the origin of the common name. Shakespeare referred to caddisses, or a worsted tape or binding, in The Winter’s Tale. Historically, cloth vendors were described as caddice men. The Oxford English Dictionary adds that caddis refers to wool or worsted yarn, but exactly how the term came to be applied to the insects is unclear.

JERUSALEM CRICKET

Stenopelmatus sp.

Stenopelmatidae family

1–2 in. long, straw colored with black stripes on abdomen, spiny legs, large jaws, large bald head

Jerusalem crickets always incite an exclamation in those who see one lumbering across the desert floor. Who would not exclaim when they saw a 2-inch-long “bug” with a head that looks eerily humanlike? Despite its appearance and its large jaws, the Jerusalem cricket is not venomous though it can inflict a painful bite. Nor is it a member of the cricket family but is closely related.

According to entomologist David Weissman, Jerusalem crickets play a central role in desert food webs by serving as meals for bats, skunks, and foxes, and by consuming plants and dead animals. Primarily nocturnal, they may sometimes be encountered during the day. Look for them under rocks, plant debris, and logs. Jerusalem crickets typically take about 20 months to mature from egg to adult with typical adults living another 2 to 6 months. During their larval stage, they molt multiple times, each time eating their cast skin.

Similar to crickets, Jerusalem crickets have a call song tied to temperature. Both sexes produce the call, which is a drumming sound, by beating their abdomen on the ground at up to forty drums per second. They use sensory organs in their legs to detect the impulses, some of which are audible to humans. Each species has its own specific drum pattern, which appears to aid males and females in locating each other.

In the western United States, there may be as many as 100 species of Stenopelmatus with at least six in southern Utah. For many years, entomologists described most American Jerusalem crickets as S. fuscus. Weissman’s research has shown this to be incorrect; S. fuscus is limited to northwest New Mexico and northeast Arizona. At this time, the most common Utah species has not been named.

Jerusalem crickets have many common names including skull insect, “child of the earth,” and potato bug. First used scientifically by entomologist Vernon Kellogg in 1905, the name Jerusalem is controversial. One entomologist believes that it “arose from a mixing of Navajo and Christian terminology,” because the Navajo called the bugs “skull insects” and early Franciscan priests in the area knew of a cliff in Jerusalem known as Skull Hill. In contrast, the term may have simply developed because Jerusalem was a common nineteenth-century swear word, leading another entomologist to write about someone “turning over a rock and in surprise, shouting ‘Jerusalem! What a cricket.’ ”

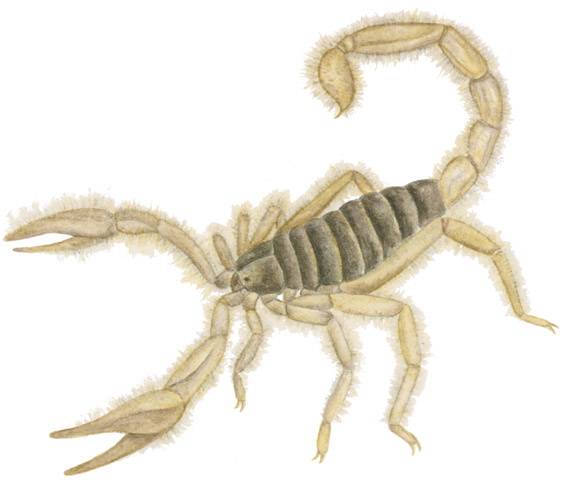

SCORPION

Variety of species

Class Arachnida

½–5 in., generally brown or tan, eight legs, with long tail, and large front appendages that end in a pincer

Scorpions are one of the most feared desert inhabitants. Although many people believe that scorpion stings (scorpions do not bite) can kill a human, most stings are no worse than that of a bee. In the United States only one species, which occurs in southern Arizona, has a venom that can kill a human. Even our largest scorpion, the giant desert hairy scorpion, has a mild sting.

Scorpions began their long adventure on land more than 400 million years ago. Along with spiders, they were one of the first animals to move onto land. Although they have remained practically unchanged in that time, they are an extremely successful group. Scorpions live in forests, grasslands, seashores, and deserts and inhabit all the continents except Antarctica. Only a few insects and spiders (principally tarantulas) reach a greater size in the world of terrestrial arthropods. In addition, their average life span of 2 to 10 years (some species can live for 25 years or longer) is greater than most other insects and arachnids.

Scorpions employ sophisticated sensory capabilities, similar to the methods used by seismologists in locating earthquakes, to locate prey. Hairs and slits on the scorpion’s legs detect subsurface vibrations, and by determining the magnitude and direction of wave propagation, a scorpion can locate its prey. They are opportunistic eaters with liberal tastes that include insects, spiders, and other scorpions.

Unlike most other terrestrial arthropods, scorpions give birth to live young. Mating occurs after an elaborate dance in which the male tries to position the female over a spermatophore that he has deposited on the ground. Gestation times range between 3 and 18 months. Females give birth to an average of 30 young. After birth the newborn climb on the mother’s back, where they remain until their first molt.

People rarely see scorpions because they are nocturnal and spend the majority of their time in burrows or under rocks. Scorpions can be seen quite easily at night, though, because their exoskeleton fluoresces (glows) under black or ultraviolet light. However, one word of caution: Remember that other animals, like rattlesnakes, do not glow and often forage at night as well.

At least six species inhabit southern Utah. The biggest are the two, hard-to-distinguish species of giant desert hairy scorpion (Hadrurus spadix and H. arizonensis) at up to 5½ inches long including tail. They have a dark brown back and live in burrows in a variety of habitats in arroyos and rocky areas. The most common scorpion is the boreal or northern scorpion (Paruroctonus boreus), which ranges from British Columbia to Nebraska. Average adult length is 2 inches. They are mostly found in sandy flats.

TARANTULA

Aphonopelma sp.

Theraphosidae family

Up to 6 in. legspan, eight legs, brown to black, hairy body

In the 1700s in southern Italy, an epidemic known as tarantism spread throughout the populace. The unfortunate people suffered through “grotesque and unnatural gestures and extravagant postures,” ultimately resulting in death. The only cure was music that induced a series of movements known as the tarantella dance. All of this was supposedly brought about by the bite of a tarantula.

Tarantulas, however, do not occur in southern Italy; between 10 and 20 species live in the United States. This much feared spider, with a legspan of up to 6 inches, rarely bites and has a mild venom that does not affect humans. Tarantulas do not employ webs to catch prey; instead they go in search or wait just inside their burrow for a meal to wander by. They eat frogs, lizards, and insects, secreting enzymes that break down soft tissues, allowing the victim’s insides to be sucked dry.

Although they seldom bite, tarantulas can create a cloud of hairs by scraping their abdomen. These urticating hairs are especially irritating to the eyes and nose.

Juvenile males and females are indistinguishable until their final molt, which does not occur until their eighth year. Males do not live long after mating. A female, on the other hand, can live for up to 25 years.

After the final molt, usually in the fall, the male goes in search of a mate. He must be careful because the larger female may eat him instead of mating with him. If mating occurs, the female will deposit roughly 800 eggs on a silk sheet that she then forms into a bag. She may carry the egg bag out of the burrow to warm it. Incubation lasts 2 to 5 months, depending on temperature and humidity. The young leave the burrow a few days after hatching and go in search of a new burrow. Juvenile mortality is high as they make a good meal for rodents, birds, scorpions, and snakes.

Besides humans, the tarantula’s main predator is the tarantula hawk (Pepsis sp.), a large wasp with a metallic blue-black body and orange wings. It can grow up to 3 inches long. The females are the hunters, and after mating, they run about searching for a tarantula who will become the food source for the Pepsis young. When the female Pepsis finds a tarantula, she attacks and stings the spider, paralyzing it. She then drags the immobilized tarantula to a burrow and deposits an egg on it. After hatching, the Pepsis larva eats the still-living tarantula. The tarantula has to be living; a dead tarantula would dry out and not be a food source. All members of this wasp family, Pompilidae, have a similar lifestyle, paralyzing spiders and using them as food for their larvae.

BLACK WIDOW SPIDER

Latrodectus hesperus

Theridiidae family

Female up to 1½ in., black with red hourglass on abdomen; male ⅓ in., gray with stripes and blotches, no hourglass

Black widow spiders are relatively common in canyon country. To find one, look in protected areas, such as rock cracks and crevices or under logs, for a sprawling web that ends in a more densely made, tubelike opening. Inside the funnel the timid female waits for food and a mate. The jet-black females have the well-known red hourglass on their abdomen, while the much smaller males are grayish with stripes and blotches. Despite their reputation, females do not actively attack males after mating. Instead, males generally crawl away from females and simply go into another part of the web to die. One could view this as a noble sacrifice, for the male provides food to the female and hence to his progeny.

Black widows also have a reputation for their poisonous bite—this one is well deserved. The neurotoxin contains seven different proteins and is one of the most highly toxic of all venoms. The bite does not hurt, but symptoms, which include intense pain, vomiting, and nausea, manifest quickly. Few people die from the bite, but children and the elderly should be cautious. Antivenin is available and hospitalization is highly recommended.

Close-up

Life in Desert Potholes

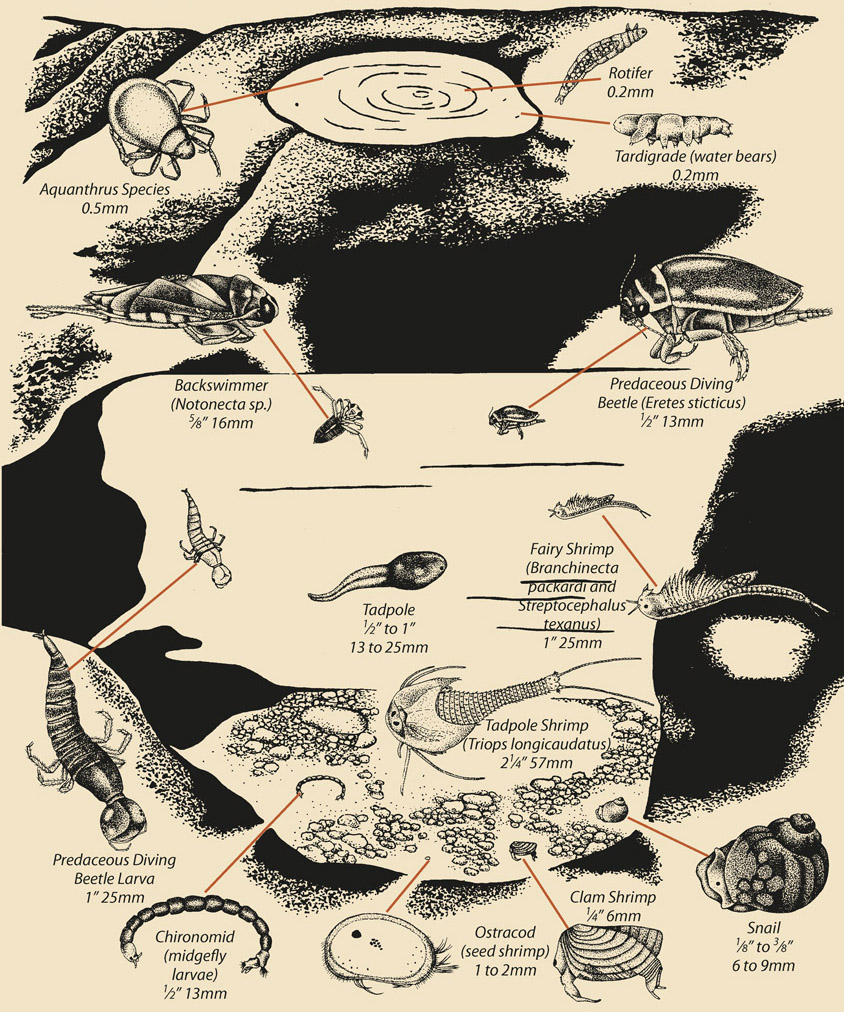

If you spend much time in canyon country, you will begin to notice that a miraculous ecosystem emerges after desert rains. What appeared to be lifeless, dirt-filled pits now begin to teem with activity. Tiny organisms, eggs, and larvae that have lain dormant in the soil burst forth with great exuberance from these potholes. In a few hours to days, crustaceans, beetles, and insect larvae begin to wriggle and squirm in the shallow pools.

Pool size and temperature are the key determining factors in what organisms inhabit a pothole. Even shallow depressions that have only a thin black coating of soil contain algae and rotifers, microscopic animals that eat algae and in turn are eaten by worms and crustaceans. If sediment is present, mites have a home. Gnat larvae and other minute organisms live in slightly larger pools. As the pool size increases, tadpoles, fairy shrimp, clam shrimp, and tadpole shrimp become prevalent. In the largest pools backswimmers, predaceous diving beetles, and midge larvae predominate.

These pothole creatures have adapted to withstand the extremes of a high desert. During the long, dry periods, organisms must be able to withstand soil temperatures that can reach 140°F (60°C) in the summer, and then remain frozen for many weeks during the winter. When there is water, an organism only has a few weeks to complete its life cycle before it dies.

Several lifestyles have evolved to cope with these extremes. Many organisms have a dormant stage in which they can resist the long periods of desiccation. They are protected by an eggshell, exoskeleton, or a coating of waterproof mud. Other organisms can tolerate an almost complete loss of water in their cells, and then rehydrate and regain all body functions in less than 1 hour after a good rainstorm. Some creatures live in more permanent water sources and take advantage of potholes only when water is present.

No matter what method they use to survive, most pothole organisms need to have a short life cycle. Red-spotted and Spadefoot Toad eggs can hatch in less than 24 hours, and take 2 to 3 weeks to develop from tadpole to toad. Compare that with a Bullfrog, which may remain in its tadpole stage for up to 2 years. Fairy shrimp and tadpole shrimp complete their life cycles in less than 2 weeks. Smaller organisms have even shorter life cycles.

The survival of pothole organisms depends upon their ability to make use of the slow, natural water cycle between periods of desiccation. Unexpected changes can kill, so if you need water, take only a little from each pothole and leave the rest. Do not jump into or swim in potholes because body oils, insect repellent, and sun-block damage this fragile ecosystem. The animals’ tenuous grip on life can easily be snuffed out when feet or tires crush them during their dry, dormant period. When that happens, we lose one of the most interesting ecosystems in the desert.

DESERT POTHOLES