When Blood Makes Way For Honey

New Albanian vocabulary: gjakmarrje (blood feud), pajtim (reconcil- iation), ahër (stable), shilte (foam mattress), me bujtë (stay the night)

Following bewildering directions in a midwinter late afternoon gloom, the tyres of our 4x4 span on the muddy streets of Dranoc. All around us were kullas built of stone, with as few windows as possible – some- times none – on the walls that face onto the street or other people’s land. Gazi had told me that kulla is actually a Turkish word meaning simply ‘tower’. The fact that it’s used for these old houses reminds you that in a period before Manhattan, when most things were single-storey, a building on three floors must have seemed dizzyingly high. But it’s no longer the height that strikes you when you arrive among a village of kullas; the book written by Norwegian anthropologist Berit Backer about her experiences living near Dranoc in the 1970s was called Behind Stone Walls – it’s these bleak, blank faces that stare you down as soon as you enter the village. The single feature relieving these walls are small holes, just large enough for the muzzle of a gun to be poked through.

So we had a sense of being watched, though no-one was about, as we drew up at the large wooden gates with some misgivings. We had come to stay the night in a kulla that had been restored by the Swedish NGO, Cultural Heritage without Borders, who were now offering it as bed and breakfast accommodation. Fear subsided slightly as the custodian opened up, welcomed us in, and took us through the low doorway (so that visitors have no choice but to bow respectfully as they enter) to the ground floor of the kulla. This would originally have been used as a stable, but now there were tables laid out for a seminar, with a PowerPoint screen covering one wall.

There was a power cut, so we made our way by torchlight up the stairs to the oda on the kulla’s top floor. It was bitterly cold, and we hurried through the wonky door. It opened onto an enchantingly cosy scene. A wooden stove had warmed the room seductively and candles were lit on a huge round table. I wanted immediately to sink down on one of the covered foam mattresses around the edge of the room, and watch the soft light flicker over mellow woodwork, the special little built-in cupboard for keeping coffee and sugar in, the bright woven cushion covers and rugs.

That’s pretty much what we did. We laid the low sofra table and cooked a simple meal with a bottle of wine. Then we lolled and chatted and relaxed in the oda’s simple luxury. I knew that I wanted to come back, and I thought of all the people I wanted to share this discovery with. The kulla in Dranoc is a unique opportunity to get a sense of a style of architecture that has otherwise almost completely disappeared. The kullas suffered in the 1990s because they were, and were suspected to be, places where KLA supplies could be safely piled. As such, they were targeted by Serbian forces and largely destroyed.

But after Serb forces withdrew from Kosovo following the NATO bombing campaign in 1999, Kosovo’s remaining kullas were still not safe. They continued to be at risk but now it was from poverty – families without enough money to mend a roof or rebuild a wall found it cheaper either to let the building disintegrate, or to knock it down and build something from concrete in its place. And ironically, the kullas that didn’t fall prey to poverty instead fell prey to wealth – specifically the dollars, deutschmarks, pounds and francs sent back by the diaspora or families’ improved economic situation resulting from the investment which followed the NATO, UN and foreign NGO arrival in Kosovo. It was now possible to buy the Slovenian roof, the modern plastic front door, the fancy balcony that kulla owners had been unable to afford previously. I could see the importance of Cultural Heritage without Borders’ work in saving this building, holding on to one small reminder of a Kosovo that was being forgotten.

We returned to Dranoc a few weeks later with Shpresa; it was in the kulla’s new fitted kitchen that she taught me to make llokuma. In February we arranged Rob’s birthday party in the kulla. Fifty people came for lunch that day, and twelve stayed the night with us, playing games in the candlelit oda until late.

But each time I checked the visitors’ book, I was depressed to see my own name as the previous entry. No presentations had been screened in the stable, and from talking to the custodian it was clear that what could have been a living, income-generating flagship for sustainable tourism in Kosovo was instead just a cold old house.

I asked the custodian for the email address of head office and contacted Cultural Heritage without Borders, suggesting that a friend and I could work as volunteers to promote the kulla. The head of the NGO, a good-looking young Albanian architect, was enthusiastic about the idea. So then I rang my friend, Cindy. Recently arrived in Kosovo from Washington DC, when she and I had had coffee together a few weeks before, she’d told me that she was looking for a project.

Was there something slightly paradoxical about a Brit and an American working to promote Kosovo’s culture like this? Well, yes, but as I had realised at Adem and Xhezide’s the day of the mushroom hunting, you can still be passionate about beekeeping and honey even if you are rarely allowed to get on with the business of beekeeping yourself. And I was increasingly passionate about Kosovo, without being a Kosovar.

We planned a series of cultural workshops at the kulla to showcase it as a space for events, over six Saturdays in October and November. We arranged an art class run by a local artist, a tasting event for Kosovan wine and raki, an Albanian language class, a lesson in Kosovan lullabies run by a professional soprano. I asked my friends for ideas for what else should be in the series? One subject kept resurfacing: ‘you can’t under- stand Kosovo – you certainly can’t understand Dranoc – if you don’t understand the Kanun.’

For my first birthday in Kosovo, along with the beehive, my presents had included a copy of the laws collected in this Code or Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini. The book’s introduction explained that the laws were only written down in the nineteenth century, but have been in existence for at least 600 years, and possibly hundreds more. Flicking through it, I learned about the rules for every aspect of social life: the correct order of precedence at a wedding, the ways that guests should be cared for – or the compensation due if someone’s bees escape.

If someone’s bees swarm and fly to the orchard or fence of another person and the owner is pursuing it, the swarm belongs to him, and the owner of the orchard or fence may not prevent him from retrieving it. If bees swarm from the hive and fly to the orchard or fence of another person and no-one pursues them, the owner of the orchard or fence has the right not to give them to anyone else and to keep them for himself. Bees that are swarming must be pursued step by step and followed until they settle somewhere, and wherever they stop they are collected by the owner.

The Kanun also specifies the going rates for a variety of commodities. The cost of a beehive with the insects inside is set in the Kanun as fifty grosh. This is the same value as 56 kilos of flour or wine, 19 kilos of meat, 11 kilos of honey, unwashed wool, raki or cheese or six kilos of coffee beans.

Whatever the charming glimpses all this gives into Kosovo’s domestic economy in centuries past, the Kanun makes some more chilling requirements too. ‘Woman,’ it says, ‘is a sack to be hard used.’ And it specifies some of the ways in which this is so, specifying that a girl has no right to be involved in decisions about her marriage, though girls would have had fair cause to be interested in what kind of man they would marry – this husband has, according to the Kanun, the right to ’beat and bind his wife when she scorns his words and orders’. There was no way out for these women: ‘if the girl does not submit and marry her fiancé, she should be handed over to him by force, together with a cartridge; and if the girl tries to flee, her husband may kill her with her parents’ cartridge, and the girl’s blood is unavenged because it was with their cartridge that she was killed.’

The careful specification of the limits of vengeance appears throughout the Kanun. The copy I was given had a blood red cover, and I began to realise more than one reason why this might be so. It is this requirement for vengeance that is the connection between Kanun and kullas. In general the principle is that for any man killed, the life of one of the murderer’s relatives must be taken in exchange. Although this was established as a limiting principle (an eye for an eye, a tooth – and no more – for a tooth) the consequence was that when the murderer’s kinsman (possibly a man who knew little or nothing of his relative’s crime – and in some case didn’t even know that the crime had been committed and that his own life was therefore at risk) was killed, that family were then eager for further retribution. In this way, blood feuds could go back and forth for generations, and each of those generations of boys and men needed a defensible retreat to keep them safe. This was why the kulla walls have holes just big enough to poke your rifle through.

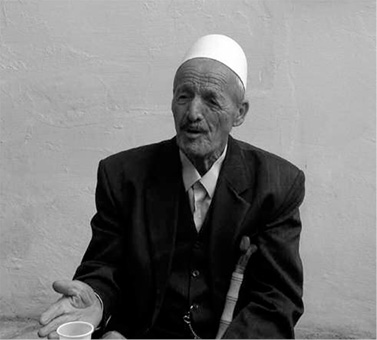

A village elder, who adjudicates on the basis of the Kanun, wearing the traditional plis hat

Cindy and I added a study day on the Kanun to our list of work-shops.

I talked to people more about the Kanun – the way that it continued to inform life in Kosovo, but also the elements that modern Kosovars had left behind. Revenge killings, for example, were almost non-existent in Kosovo now, largely due to a campaign of reconciliation during the 1990s, led by a perhaps incongruous figure – a Kosovan folklorist, Anton Çetta.

Çetta was one of the first characters I had met during my immersion course in Kosovan history; two copies of the same statue of him stand in the front garden of a sculptor in central Pristina. I walked past that house to get to the Ethnological Museum and grew used to seeing the twin men gesturing at me with outstretched palm as I passed, the outlines in their blazer pockets showing that they were men of the book. When winter came, the snow settled on their heads, giving them small white hats just like those that the real life old men wear in the streets of Pristina.

During Çetta’s travels around Kosovo to collect examples of folk- lore, he became aware of how paralysed his country had become because of the blood feuds. While the Albanians of Kosovo were being targeted by the Serbian authorities, Çetta could see the importance of solidarity between themselves, and he set about organising enormous formal ceremonies of reconciliation for hundreds of families ‘in blood’ with each other.

Unsurprisingly, given this rich history, bookings started coming in for the Kanun workshop as well as the others we’d advertised. Almost everyone due to attend was from Pristina – a mixture of foreigners and Albanian Kosovars, with a disproportionately large number of the former, despite the reduced rates we were offering for people on local salaries. But Cindy and I didn’t want the workshops just to be opportunities for city folk to lumber down to the country in their 4x4s, leaving nothing but tyre tracks in the churned-up mud lanes of the village to show they had been there; we wanted to offer some benefit to the people living in Dranoc.

To talk to the families in the village we didn’t have to do anything more than walk through the streets. We looked conspicuously foreign, and when we passed someone, Cindy smiled and I used an Albanian greeting. Cindy would always draw attention, and Albanians, both male and female, are great appreciators of feminine beauty; where English women might snarl, Albanian girls will admire frankly. It was never long before we would be in conversation about just what we were doing in Dranoc; I was confident enough now in my language skills to strike up these conversations with strangers. Almost without exception we were then invited in for coffee and over our coffees we explained more about why we were here. We presented the workshop as an opportunity for people in Dranoc to sell things (and keep all their takings) – perhaps handcrafts, or home-made cheese, raki... Honey? I suggested.

It was coming up to elections, and one of our hosts told us that people in this village had nothing to sell ‘except their votes’. One wrinkled old man with lively eyes countered that Dranoc might be able to rustle up some women for sale if the people from Pristina were interested. But it wasn’t that kind of honeys I had been hoping for.

On our walk we met Syzana, an 18-year-old who lives with her parents and five brothers and sisters in a plasterboard house near the kulla. She invited us to supper at her home, where we were met at the door by a pinprick of torchlight in the power cut. It threw strange shadows on our faces, as her parents welcomed us in, and we picked our way through the shoes outside the door into the little house.

Syzana’s father apologised for the humble home he was hosting us in. ‘Our house was destroyed during the war, when we were hiding up in the mountains.’ He gestured to the sheer rock face that forms the border with Albania, rising up behind the village. The mountains’ Albanian name means ‘accursed’. I looked round the family, at their pretty little daughter who would have been only a baby in the war, at the son who limps; I imagined them all sheltering out there in the night, cowering, listening, hushing the children.

I used the toilet in their house – a tiny bathroom where you had to step over the plastic water bottles filled when there was water on tap, and stored up for the hours, or whole nights, when there was none in the pipes. There were small stickers on the doorways with Japanese lettering – the temporary shelter had been the gift of a Japanese aid agency. Eight years on, with two additional children, the family was still crowded into it, and no member of the family had work outside the home.

Back in the family sitting room, we were gathered round the only light, a saucer of sunflower oil from which trailed half a dozen short cotton threads that acted as feebly-glowing wicks. After we had eaten, Syzana’s mother handed us chunks of her nettle pite pie wrapped in newspaper to take back with us – in our Landrover to our centrally- heated house, stuffed with its imported luxury food. And Syzana opened up her suitcase of handicrafts – the poorly-lit hours she had woven together evening after evening in the cold front room into endless fine table mats and pretty coffee cup holders. Before we knew it, three little crocheted doilies were being packaged up for us to take home too. But the family wasn’t sure about bringing any of these to sell to our visitors.

The following weekend the first workshop opened at the kulla. Two television crews and a documentary film-maker poked the long noses of their cameras round the door to the oda, and journalists lolled on the mattresses with their notebooks. As each workshop participant arrived I greeted them and escorted them up the stairs to the oda. So I had the chance to relive fifteen separate times that thrill as the door which was hung askew on its hinges swung back to show the room’s elegant simplicity, the old wood and weavings, the warm stove.

But not a single person from the village came offering to sell their honey, or anything else. I talked to one of the Americans who’d come to the workshop. ‘Elizabeth, the concept of selling surplus is very sophisticated – too sophisticated to be grasped by people who live by subsistence farming.’

When the workshop had finished, I went out again around the village, visiting new houses, hoping to generate some interest in bringing things to sell next week. More coffee, conversation, explanation, offers, and still no suggestion that anyone would take up the opportunity the following Saturday.

Six days later we were back, in the company of a young Kosovar who had trained as an oenologist. Over supper the night before his workshop he told us about Kosovo’s previously productive wine industry, despite the vineyards that had been abandoned since the war. He poured us samples from some small vineyards that had been restarted recently – peppery Merlot and a berry-rich Cabernet. The old state- owned vineyard had been privatised recently and we tried some other good red wine (and some less good white) from there. ‘You’ll have drunk this before,’ Albert smiled. ‘Most of it went for export under a Yugoslav label before the war.’

As we set up the glasses for his tasting workshop the next morning, there was a knock on the front door. Syzana was standing outside. We asked how she was, was she tired? In answer, she gestured to the plastic bag she had with her, and pulled out some table mats which she and other members of her family had beaded and crocheted. I could have kissed her.

In fact, I did.

Of course, the visitors to the workshop loved her work. Syzana sold almost everything she had brought, and she asked if she could come back the following Saturday. When she returned the next week, Syzana brought her friends with her. They laid out their handmade beading, their ubiquitous table mats. One brought a brother who had walnuts, homemade cheese, corn flour. And someone else brought honey.

The Mazrekaj kulla in Dranoc where our workshops were held and honey sold

The honey was a runaway success and the beekeeper sold out. He was selling it at seven euros a kilogram – cheaper, and definitely tastier, than you can buy it in the Pristina market. If my maths is right, then Lekë Dukagjini would have found it a bargain too: proof, if any were needed, that it’s better to live on local honey than it is to survive on coffee, wine – or unwashed wool. And our sales confirmed that even the beekeepers who don’t get their hands dirty as much as they would like do still have a part to play in supporting honey production.

Putting the pite into hospitality

Although I later returned many times to Syzana’s house and ate more of the excellent pite I never watched it made there from start to finish. One day, on a flight to Pristina, I was discussing with the Albanian woman sitting next to me how I’d like to know how to make the dish. ’Would you, by any chance, know a recipe?’ She was kind enough to dictate one to me as we sat in the clouds a mile above Eastern Europe. Sometimes, when I wasn’t clear about the details of what she was describing, she used her airline meal napkin to demonstrate the layers of the pastry, just how you pinch them together. I apologised for interrupting her journey but she waved away my apology. ‘It’s good,’ she said. ‘I want my daughter to learn too.’ The 23-year-old next to her was her daughter, and it emerged that the reason it would be particularly useful for her to learn the art of good pite-making was that she was on this flight to Kosovo to celebrate her engagement. Two months previously she had been visiting Kosovo from her home in Finland and her grandfather had suggested the son of his next-door neighbour as a suitable husband. The couple and their parents met and confirmed that the match would be a good one (I think he is a very lucky man – Ardita is beautiful and also has ‘papers’ in Finland), so now only weeks later, this plane journey was the beginning of their life together. Ardita will bring her husband back to Helsinki, where she will no doubt, as her mother has taught her, cook exquisite things for this near-stranger. I suggested to her that she was very brave to be starting a new life like this. She shrugged: ‘my grandfather knows his family’ – as if that was all the assurance any girl needed.

When my friend Valbona heard about Ardita’s mother’s recipe she was sceptical. Different areas of Kosovo have very different approaches to pite-making and she offered to share her version with me. What follows is my combination of the two recipes.

Ingredients

For the pastry

900g plain flour

1tsp salt

approx. 550ml warm water

plus 1 tbsp oil to glaze

For the filling

250g nettles – remove stalks

1 small onion

1 egg

125g yoghurt

100ml single cream

salt to taste

Measure out the flour into a deep bowl. Add the salt and water until the dough is the ‘right’ consistency (when I queried what this meant I was given a simple guideline, which I learned later was not of Valbona’s own devising. The mixture should feel like the flesh in your earlobe. Try feeling your earlobe now and you will see what a useful guide this is). Knead the dough on a floured surface (Valbona uses the heel of her right hand while her left spins the ball of dough in a movement I couldn’t reproduce however hard I tried). Cover with a plate to rest.

Chop the nettles finely and wash them twice in hot water then 2 or 3 times in cold water. Drain.

Chop the onion finely, and fry to soften it.

Mix the nettles and onions together. Add the egg, crème fraiche, flour, milk and salt, and mix together.

Return to the dough and form into 25 balls a little larger than golf balls. Gently knead each of these using a motion from the heel of your hand down your thumb, and roll each of them out to 10cm diameter.

Take one of the circles you have made and spread oil on top of it. Place another circle on top and drape these two over the fist of one hand so that the discs begin to distend with their own weight. With your free hand stretch the discs further. Repeat this process with new discs, pulling the pile to increase its diameter with each new addition, until you have a stack of 7 discs of 40cm diameter.

Repeat the process to make another stack from the other 6 balls.

Oil a tepsi and line it with the 7 layers, making sure they go up the sides.

Cover with the filling.

Place the 6-layer stack on top of the filling and pinch and twist the edges together to seal the filling in.

Spread oil on top of the pite. Prick the pie with a fork and place in a200°C oven for 35-40 minutes.

The pite is served in slices like a pizza.

It is often made with spinach and/or the white crumbly cheese, or with pumpkin.