2

The SL – born on the track

The Mercedes-Benz racing team had attained legendary status in the 1930s, with its silver cars hitting the headlines in virtually every country they appeared in. But the war had broken up the equipe, and it wasn’t until March 1952 that Mercedes returned to the racing world with a purpose-built factory-backed car. This development marked the birth of the SL ...

With the cessation of hostilities and a gradual return to normality in the industrial nations of the world, Alfred Neubauer wanted to return to Grand Prix racing as quickly as possible with new versions of the pre-war W165 voiturettes, but almost as soon as the production order was granted, it was withdrawn again. A meeting of the hierarchy in Stuttgart concluded that if Neubauer wanted to go racing in 1952, it would have to be with sports cars representing the marque, and any plans to enter a GP machine should be delayed until 1954, when a new formula was set to be introduced.

With classic events like Le Mans, the Mille Miglia and Targa Florio revived, sports car racing was extremely popular following the war, as it was a perfect way of promoting a brand in a manner that allowed enthusiasts to readily relate a victorious machine with a showroom model they could buy, or at least dream about. The need for Europe to export led to an explosion of LWS models, with England leading the way, supplying an American market that was taking as many cars as the ships crossing the Atlantic could carry.

Sports car racing also appealed to those looking after company finances, as road vehicle technology could be developed and tested within the competition department budget – killing two birds with one stone, so to speak. For instance, the C-type Jaguar that had won Le Mans in 1951 was based on XK120 components, and lessons learnt during the 24 hours could then be applied to produce a better road car. In the case of the Mercedes-Benz team, the three-litre W186 II chassis was deemed to provide a suitable starting point for a new kind of sports-racer.

W194: The first SL

The W194 concept was much the same as that of the Jaguar C-type, using as many proven XK120 parts as possible in a custom-made, lightweight frame, and enhancing power output largely via modifications to the cylinder head and carburetion. The model selected as the donor car by Daimler-Benz was the new, upmarket Type 300. It may seem an unlikely vehicle, but it was the powertrain that appealed, and one has to remember that the XK engine also powered limousines, not just sports cars, so the parallel between the Coventry and Stuttgart companies is still valid.

One of the first press pictures of the new 300SL (or 300SS as it was nearly called), with the shut line on the ‘gullwing’ doors finishing on the top of the vehicle’s waistline. Note also the bolt-on wheels, finished with hubcaps – remarkable detailing for a racing car!

The three-litre engine – considered the main component to work around – and the Mercedes-Benz 300 model it powered were introduced at the 1951 Frankfurt Show, which opened on 19 April. The short-wheelbase 300S coupes and convertibles made their debut at the Paris Salon six months later, but already plans were at an advanced stage for a sports-racer built around the luxury saloon’s straight-six – the engineers in the racing shop, under the direction of Rudy Uhlenhaut, didn’t have to wait for the more sporting variant (which came with a tuned powerplant delivering 35bhp more than the regular unit) before embarking on their project.

The sohc M186 base six had a 2996cc displacement (85 x 88mm bore and stroke), and with a pair of Solex carburettors and a modest 6.4:1 compression ratio, produced a lazy 115bhp at 4600rpm. Endowing the unit with three downdraught Solexes, a freer exhaust system, and a hotter camshaft, then hiking the c/r up to 8.0:1 (via special heads and pistons), released an extra 60 horses according to official data, while maximum torque stood at 188lbft.

Rather than sitting atop a backbone chassis, as used on the 300 saloons, the straight-six and its modified, all-synchromesh four-speed transmission was placed within a purpose-built tubular spaceframe, produced in steel and designed using the most up-to-date racing car practices. For the 300SL project, the power-unit was tilted over at a steep angle in order to allow a low body-line, despite the height of the engine.

A dry-sump lubrication system was added at an early stage after testing proved the regular system inadequate for the rigours of competition work, and the sparkplugs were moved to a new location to allow quicker changes to be carried out. As such, a different block was made for the W194 project, although it was still made in cast-iron. With all of the modifications in place, the racing unit was given the M194 moniker.

As for the chassis components, steering came courtesy of the familiar Daimler-Benz recirculating-ball system found on the other 300 series models, while the all-round suspension was also similar to that of the 300 road car, with double-wishbones and hydraulic dampers placed inside coil springs at the front, and a swing-axle arrangement at the rear, which employed separate springs and telescopic tube shocks.

Rudy Uhlenhaut checking progress on a 300SL. Note the spaceframe and the way the engine was angled over to keep the bonnet line as low as possible.

The first pictures released showed bolt-on wheels (complete with hubcaps!), although knock-off hubs were adopted to allow for quicker wheel changes. A 15-inch wheel and tyre combination was specified, with alloy rims playing host to Continental racing rubber. Beyond the wheels, there were drum brakes on all four corners, finned for enhanced cooling, while those fitted at the front of the car had a greater friction material area than the 300 saloon’s brakes due to their extra width.

As for the body, in addition to the obvious aerodynamic concerns, assuming there was adequate ventilation, a closed coupe configuration also improved driver comfort and concentration, as sports car races tended to be long, and were often held in awful weather – buffeting from an open car at high speeds can be tiring, and no driver could be expected to give his best performance whilst cold and soaked through either.

Novel ‘gullwing’ doors were introduced to keep the spaceframe as stiff as possible, as regular doors require a large cut-out in an area that is critical in retaining chassis strength. It was an ingenious idea, typical of the Daimler-Benz competitions department, with the original doors being no more than windows that tilted upward to allow the driver access to the well-trimmed and beautifully prepared cockpit. However, the design was modified in time for the Le Mans race, with slightly deeper doors that pleased the folk at the ACO but lost little in the way of structural rigidity.

The wheelbase was set at 2400mm (94.5in), as opposed to 2900mm (114.2in) for a production 300S, while the height, at 1265mm (49.8in), was some 245mm (9.6in) lower, helping reduce the car’s centre of gravity by a large amount. The front track was narrow to keep as much of the front wheels underneath the aluminium bodywork as possible, aiding aerodynamics, while the rear track was wider to allow the swing-axle to work efficiently at high cornering speeds.

The two spare wheels and fuel tank were placed in the tail of the car to provide better traction, and provide a balance for at least some of the weight of the powerplant up front. The aluminium-bodied 300SL was hardly lightweight by absolute standards, but, at 870kg (1914lb), it was half the bulk of a regular 300S coupé.

The first prototype was ready for testing in November 1951. Neubauer wasn’t happy, demanding more power, a five-speed transmission, and bigger brakes behind a 16-inch wheel and tyre combination. However, budget and time restrictions ruled out any further changes.

March 1952 witnessed the press presentation of the new car, with motoring scribes leaving Neubauer out in the cold. As an enthusiastic John Whitten wrote in Road & Track at the time: “The three-litre car, according to its specifications alone, should be a winner; but when you couple it with the name of the team which is to drive it in competition, it sounds like an unbeatable combination: Rudolf Carraciola! Hermann Lang! Karl Kling!”

Whitten obviously still had lucid memories of the men that handled the Silver Arrows in the heyday of pre-war racing. But there’s little doubt that the Mercedes-Benz team had strength in depth, and the advantage of Alfred Neubauer running things from the pits. Neubauer may not have given the 300SL project his full support, but he was not a man to let personal reservations dampen his determination to win.

The first race for the 300SL was the Mille Miglia, held in the first week of May, and taking in almost 1000 miles (1564km, as it happens) of Italian roads on a return trip to Brescia via Rome. Naturally, the three works cars were painted silver! The Lang/Grupp machine was forced into early retirement, but the Kling/Klenk pairing was second, less than five minutes down on the winning Ferrari, whilst the Caracciola/Kurrle SL came home in fourth.

The next event, the sports car race before the Grand Prix in Switzerland, was basically a shakedown for Le Mans, and a chance to try a new door arrangement on the fourth works entry. Sadly, Caracciola had an accident that brought his career to an end, but the remaining cars all finished on the podium, much to the chagrin of the Ferrari contingent, and the deeper doors were approved for the 24-hour race at the same time.

Three works cars were entered for the 1952 Mille Miglia. This is the 300SL of Karl Kling (right) and Hans Klenk.

The modified car used in Berne (chassis 006/52) was rolled out as a spare at Le Mans, joined by three brand new cars with the deeper ‘gullwing’ doors. The spare car was used in practice to try an experimental, roof-mounted air brake, and, whilst it wasn’t used in the race (more work was definitely needed on the design), the concept was good, and it would be seen again on later Mercedes-Benz sports-racers.

Although the Kling/Klenk SL dropped out with electrical problems, the Jaguar threat soon disappeared when the new streamlined bodies presented unforeseen cooling difficulties, and the Ferraris buckled under the fast early pace. The engine in Pierre Levegh’s Talbot-Lago gave way whilst he was in the lead, leaving Neubauer’s team to take the spoils, with the Lang/Riess car taking the flag, and the Helfrich/Niedermayr machine coming second, 14 laps ahead of its nearest rival. In the process, the 300SL duly became the first closed car to win Le Mans.

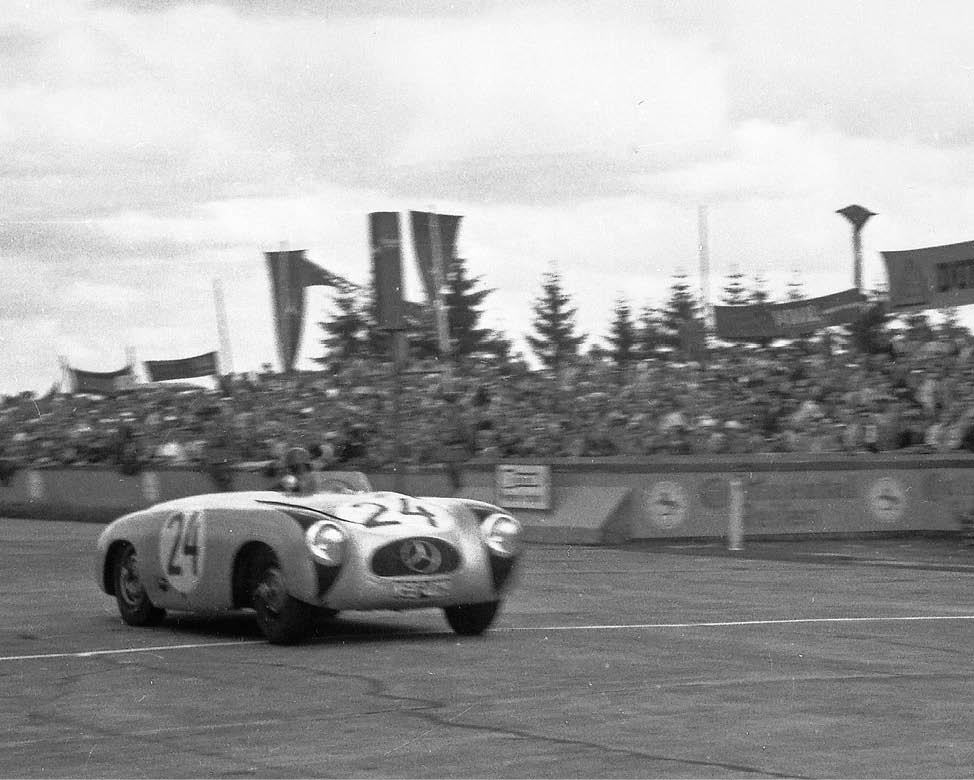

Action from the sports car race held in Bern, Switzerland, on 18 May 1952. The 300SL of Rudolf Caracciola can be seen leading two of the three sister cars entered in the event. Victory ultimately went to Karl Kling in the number 18 machine.

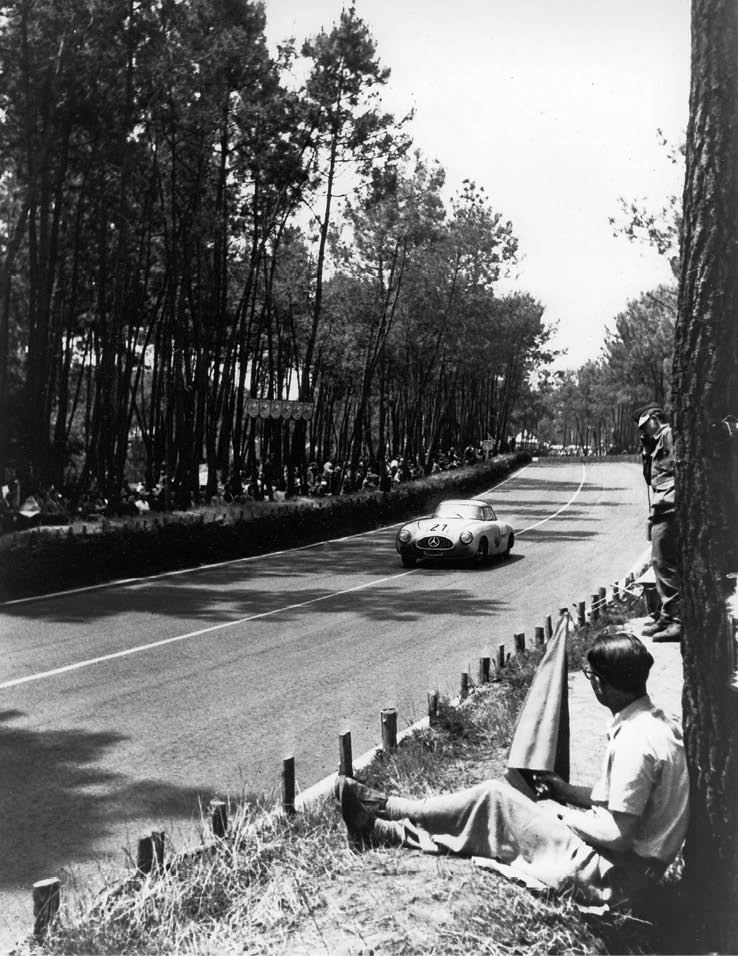

Three brand new 300SLs were built for the 1952 Le Mans 24-hour race, each incorporating an extended door, and a new fuel filler arrangement.

British advertising making the most of the SL’s success in Switzerland.

The Mercedes-Benz 300SL of Hermann Lang and Fritz Riess in action at Le Mans, en route to a fine victory in the 24-hour classic.

The roadster version of the 300SL, this particular car being chassis 006/52. Several windscreen variations were made – this one, combined with a tonneau cover, being for shorter track races, where no passenger was carried. On longer events, when a co-driver was required, a full-width screen was fitted.

Mercedes-Benz dominated the field at the Nürburgring in August 1952. The works 300SLs filled the first four places in this German Grand Prix support race.

Next up was a German Grand Prix support race at the Nürburgring, and naturally, it was important for Daimler-Benz to put on a good show in front of a home crowd. As a short-distance sprint event, running the cars as light and powerful as possible was the key to success, acknowledgement of which came with the birth of the 300SL roadster.

Due to the spaceframe chassis, it was fairly simple to convert the W194 from a coupe into an open car, and thus reduce weight effectively as additional bracing was hardly necessary to retain rigidity. A one-off shortened version (chassis 010/52) was built, powered by a supercharged M197 engine, but traction (and early reliability) was a real problem, and the four works spiders all ran with normally-aspirated units. Lang won in 007/52 (the Le Mans winner with its new body configuration), followed home by his three team-mates.

A last minute decision was taken to enter the SL in the Mexican road race called the Carrera Panamericana, with two coupes and a roadster handled by top class drivers. The engines were bored out to give a 3105cc displacement, thus releasing a few extra horses, as this was indeed an event in which power was king. Ultimately, John Fitch was disqualified in the open car, but the coupes overcame early tyre problems to finish one-two in a convincing display of German efficiency.

Unfortunately, the 300SL programme was cancelled long before the 1953 season started, but it was certainly a useful exercise, both from a publicity and an engineering point of view. Even the supercharged roadster debacle led to the development of the low-pivot swing-axle, which would later become a signature feature on Mercedes-Benz road cars. As the old saying goes, racing improves the breed ...

A rare contemporary colour shot from the Carrera Panamericana. This is the car shared by Hermann Lang and Erwin Grupp.

Kling and Klenk had a vulture go through the windscreen on the first stage of the Carrera. The vertical bars seen in this picture were fitted soon after to protect the new window glass.

The roadster of John Fitch and Eugen Geiger was running well in Mexico, but was disqualified for accepting assistance outside an authorized service area.

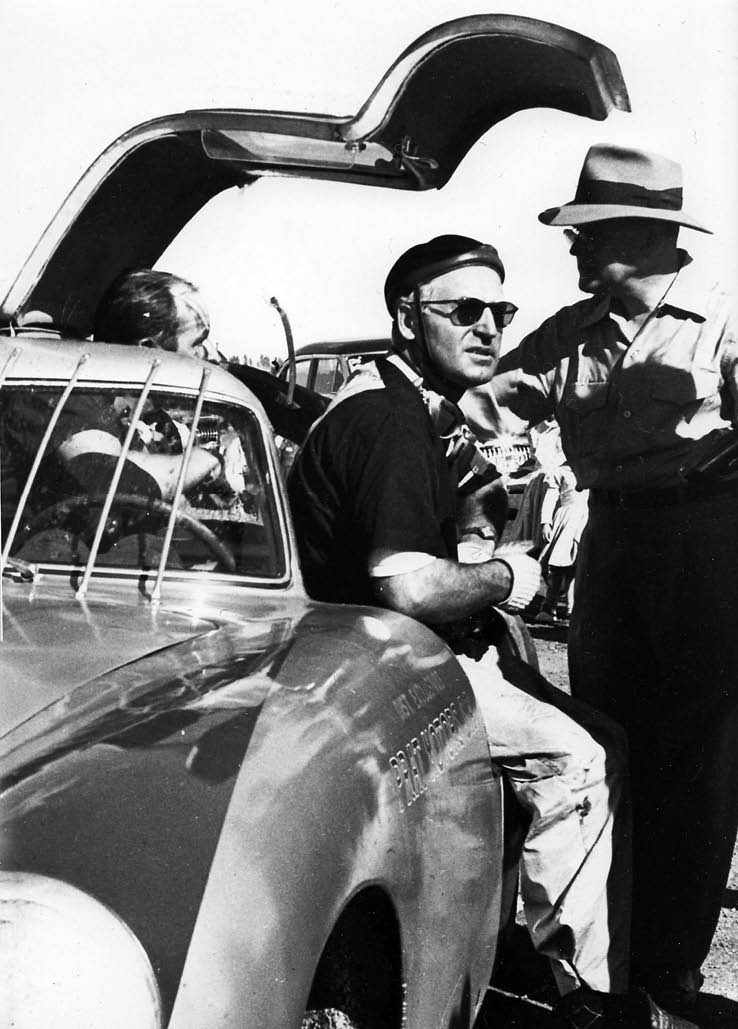

Karl Kling taking a well-earned rest during the Carrera Panamericana, an event he went on to win.

Plans were drawn up for a lighter, narrower car for 1953, complete with a fuel-injected engine, a transaxle at the rear, a modified rear suspension incorporating a low-pivot swing-axle, and a 16-inch wheel and tyre combination. However, the project was cancelled in favour of putting greater effort into the 1954 Grand Prix car and the 300SLR allowed to be based on it. Only one prototype (chassis number 11) was built as a result.

Rudolf Uhlenhaut

A key figure in the birth of the 300SL was Rudolf Uhlenhaut, born in July 1906 to a German father and an English mother. Uhlenhaut was put in charge of the new racing shop at Daimler-Benz, established in 1936 to bridge the gap between Neubauer’s arm of the experimental department and the central design office. It was a huge responsibility for the young man. However, Uhlenhaut quickly proved he had the technical knowledge and enough skill behind the wheel to make him the perfect man for the job. He was able to lap a Grand Prix car on a par with the best of the Mercedes-Benz team members, and his logical mind, combined with his exceptional level of mechanical sympathy and feel, enabled many problems to be ironed out quickly and efficiently.

As Stirling Moss once said: “He could drive any of the cars nearly as fast as we could. In the 1930s, his performances merited a regular place in the team, but he was too valuable as an engineer to be risked in a possible accident. Apart from his great influence on the design of the cars, it was he who would do everything to see that the driver had the sort of car he wanted ...”

Uhlenhaut was responsible for making the Silver Arrows into winning machines in pre-war days, and also for breathing life into the SL series, taking the notes and drawings made in numerous meetings involving management, engineers, designers and drivers, and transforming them into a car that would form the foundation stone for a new generation of Mercedes-Benz legends ...

Rudy Uhlenhaut.

The Silver Arrows

Even today, mention of the Silver Arrows immediately conjures up an image of a golden age in the 1930s when Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union dominated the Grand Prix scene with their highly advanced, but technically quite different, machines. Like Daimler and Benz in the veteran era, there was a healthy rivalry between Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union, with the two forever being inextricably linked.

The Silver Arrows legend was born when the W25 was designed to compete in the new 750kg formula devised for the 1934 Grand Prix season. They started life finished in German racing white, but were stripped of their paint to save enough weight to qualify for their first race, and became silver by default! Silver then became synonymous with the Mercedes works team, as well as that of the rival Auto Union camp.

Rudy Uhlenhaut was responsible for refining the highly-successful W125 that followed, a car that won many of the big races of 1937. When the formula changed again, Mercedes-Benz responded with the W154, powered by a three-litre supercharged V12, and, with the contemporary Auto Unions, German domination of the race tracks unfolded. Even the Italians changing the rules for the 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix couldn’t stop Mercedes winning with a 1.5-litre W165 model, built from scratch in an unbelievably short space of time.

As well as the cars and their heroic drivers, the name of Alfred Neubauer came to the fore as the perfectionist manager of the Mercedes-Benz team. Neubauer had been a racing driver himself, competing in the Porsche-designed Mercédès models of yore. As a matter of interest, there was another link between these Stuttgart neighbours (Porsche and Mercedes, that is), as Daimler-Benz had built some of the early Volkswagen prototypes – the VW Beetle being one of Professor Porsche’s most acclaimed designs.

After the war, the Silver Arrows returned to the track, first via the Mercedes-Benz 300SL, and then more specialized versions of the model. By 1954, Neubauer’s dream of a return to Grand Prix racing had materialized, and another era of domination began ...