5

5

FRANÇOIS QUESNAY (1694–1774)

The origins of “laissez-faire”

Even the minority of people today who have heard of the “physiocrats” tend to regard them as little more than a historical curiosity. This group of French thinkers (they called themselves “philosophes économistes”) was active for only a short period in the mid-18th century, and are mainly known for their odd argument that agriculture was the only true source of a country’s wealth. In their opinion, stuff like manufacturing or industry did not matter at all.

Yet the physiocrats–and especially their leader, François Quesnay1–have more to offer than strange theories about farming. In their writings we find perhaps the first attempt to view the economy as a scientific, mathematical system, most famously with the publication of Quesnay’s “economic table” (Tableau Economique). The physiocrats’ work is intimately associated with the notion of “laissez-faire”, the approach to economic management that emphasises minimal governmental intervention. And understanding what the physiocrats were trying to do is a way of understanding 18th-century French politics more broadly.

The practice of grouping thinkers together under a common name is often rejected by the grouped. The mercantilists were not really a cohesive group, for instance. The physiocrats were different, though. They embraced the term, using it in their writings and considering themselves as belonging to a “school”. (Indeed, some people at the time accused them of being part of a sect.) Their undisputed leader was François Quesnay. “No member of this group”, writes Thomas Neill, a historian, “made any pretention [sic] to originality; each professed only to be popularising Quesnay’s ideas.”

Born in 1694 in Montfort-l’Amaury, not far from Paris, Quesnay was first and foremost a medical doctor. When Adam Smith (1723–90) visited France with his tutee, the Duke of Buccleuch, and the duke fell ill, Quesnay was sent for. He was one of four physicians to Louis XV (1710–74), as well as the doctor of Madame de Pompadour (1721–64), Louis’s official mistress (in the words of one biographer, he was “discreet” in his medical service). Despite living in France, Quesnay was a fellow of the Royal Society in London, and was responsible for some important medical advances. He wrote an important book on the subject of bloodletting, a common medical practice at the time. When the Académie royale de chirurgie was founded in 1731, Quesnay was selected as its secretary.

The lay of the land

In his sixties Quesnay turned his attention to economic problems. The core of the physiocrats’ economic beliefs was that agriculture was the only source of value. In a lecture given in 1897 Henry Higgs of the London School of Economics tried to explain what this meant in simple terms. It boils down to this: “If the owners of land shut off their property and allowed no one to labour on the soil, there would be neither food nor clothing available. Every inhabitant of a state is therefore, in a sense, dependent upon the landowner.”

In other words, all economic activity begins with the agricultural sector. Another way of thinking of it is to say: if people cannot eat, nothing else happens. What the physiocrats called the “sterile” sector of the economy (ie, industry and manufacturing) depended on the “productive” (ie, agriculture) sector not only for its raw materials but also in the sense that agriculture put money in the pockets of farm workers who could then buy chairs, tables and clothes.2 It followed that to improve overall economic prosperity, having a thriving agricultural sector was essential.

Quesnay made another argument in favour of a strong agricultural sector. Demand for agricultural produce was pretty reliable, he noted–in modern jargon, he would have said that demand was highly “inelastic” with regard to price. Whatever happens, people need to eat–and they will cut spending on almost everything else before they cut spending on food. So he reckoned that, if a country faced the choice between exporting food and exporting, say, luxury goods, the former option was always the better one. As he put it, “when times are bad, trade in luxury goods slackens, and the workers find themselves without bread and without work”.

The physiocrats’ obsession with agriculture may strike you as daft. Many rich countries got rich without farming. It forms precisely 0% of Singaporean GDP, for example. In 18th-century France, however, the agriculture-is-best argument would have sounded perfectly reasonable. It would not even have struck people as a “physiocratic” theory, as it was a central part of the primitive economic thought of antiquity and the Middle Ages. Adam Smith, who knew Quesnay, appeared to have similar views. According to Tony Wrigley, Smith “insisted that investment to improve the agricultural capacity of a country must always constitute the most beneficial use of capital”.

Missing the point

The thing you have to ask yourself, though, is this: did the physiocrats truly believe their own theory? The crucial context for these theories is that, at the time, France had been living through decades of mercantilism (see Chapter 1). The physiocrats noticed the damage mercantilism was doing and wanted to rid it from their country. They needed an extreme theory in order to convince the powers that be that something had to change.

In the 1750s and 1760s, the French establishment worried about how weak their country had become. The War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48) had been a complete failure. The Seven Years War (1756–63), often considered to be the first global war, had been even worse. In part because of these misadventures, the French state was perpetually on the verge of bankruptcy (indeed, the government repeatedly defaulted on its debt obligations during the 18th century). The mercantilist policies of Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–83) surely compounded these problems. French economic growth per person during the 17th century was practically zero; by one estimate, French GDP halved in the 30 years to 1700. The French enviously looked over the Channel to England, which seemed to be doing pretty well. England’s navy was gradually assuming global dominance. Its economy was booming.

The French establishment thought about how to put its country back on track. As Thomas Neill points out, in the 1760s “a number of new journals were established, and licenced by the government, for the express purpose of carrying articles on economic and financial subjects”. The Gazette du commerce, d’agriculture et des finances was established in 1763, “the prospectus of which announced that it had been given the exclusive privilege of treating economic subjects for thirty years”. (No one appeared to recognise the irony of giving a monopoly to a journal that advocated free trade.)

The physiocrats were a big part of this debate. They had a definite idea of what had gone wrong. France, the argument went, had forgotten the lessons of earlier thinkers, such as John Locke, which held that agriculture was the foundation of all wealth. Under the malign influence of Jean-Baptiste Colbert the government had instead imbibed mercantilist doctrine. According to that doctrine, wealth was really measured by how much bullion had been accumulated. That implied subsidies to manufacturers, who could export lots of items to get lots of bullion from abroad. It also implied restrictions on the export of grain,3 in order to push down its price and reduce the costs for bosses in the manufacturing industry. France began to produce a wealth of pointless luxuries. But development in the agricultural sector had been stymied by the imposition of artificially low prices. In sum, the “moneyed” interest, represented by manufacturers, had won out at the expense of the landed interest, represented by farmers. And this had led to France’s ruin.

An issue of the Farmer’s Magazine, published around the same time, showed how far French agriculture had fallen: “In 1621 the English complained that we [France] sent them wheat in such quantities, and at so low a price, that their own produce could not support the competition… Our agriculture continued to prosper [until] Louis XIV, when a system commenced, by which the exportation of grain was prohibited.” That was not the only problem with French agriculture. Quesnay loathed the “métayer” system of agriculture, a form of smallholder sharecropping dominant in pre-Revolutionary France that was highly inefficient, largely because tenure was insecure and thus farmers had little incentive to invest in more productive methods. Taxes, meanwhile, were heavy: “at the peasant’s own door”, says Henry Higgs, “were the innumerable fees… due to his feudal lord.”

Something had to change. France, the physiocrats argued, had geographical advantages that could make it an agricultural powerhouse once again. Quesnay referred to France’s “navigable rivers [and] its very extensive and fertile territory”. As A. L. Mueller puts it, “the physiocrats agreed that in spite of the dismal conditions prevailing in agriculture, caused largely by misplaced mercantilistic policies, the country was clearly one whose advantage lay in the field of agricultural production”. The Encyclopaedia of Agriculture, published in 1821, noted that “France is the most favourable country in Europe for agriculture; its soils are not less varied than its climates.”

Quesnay saw no reason why French agriculture could not rescale the dizzy heights of 1621. Once again France would force the English to complain about the cheapness of their exports. For one thing the métayer system had to go, with large-scale agriculture taking its place. And France had to embrace free trade in food. Foreign sales, according to Quesnay, would “support the price of foodstuffs”–the world price could be higher than the domestic price that farmers could get for their produce but was unlikely to be lower. Free trade was a pre-condition for a successful agricultural sector, since it would in his words “lead to more stable and generally higher prices for agricultural products, which would permit increases in production, higher profits, and a greater reinvestment than before”, says Mueller.

In that sense, to argue that “the physiocrats only valued agriculture and therefore the physiocrats were stupid” is to miss the point. Quesnay and his followers had a clear political objective: trying to bounce French administrators into helping a sector that was clearly struggling, with a view to improving the overall French economy.4 Adam Smith believed that the rise of the physiocrats was an almost emotional reaction to Colbertism, which in part explains why it is such an extreme theory:

If the rod be bent too much one way… in order to make it straight you must bend it as much the other. The French philosophers, who have proposed the system which represents agriculture as the sole source of the revenue and wealth of every country, seem to have adopted this proverbial maxim; and as in the plan of Mr. Colbert the industry of the towns was certainly over-valued in comparison with the country; so in their system it seems to be as certainly under-valued.

Quesnay had decided, long before he sat down to write about economics, that French agriculture needed to be given a boost. The theory he devised fitted the conclusions that he had already reached.

Whatever the origins of the theory, it had clear policy implications. From 1763 the French state did, indeed, free up the trade in grain, both nationally and internationally.5 Quesnay died in 1774 a happy man.6

The table of truth

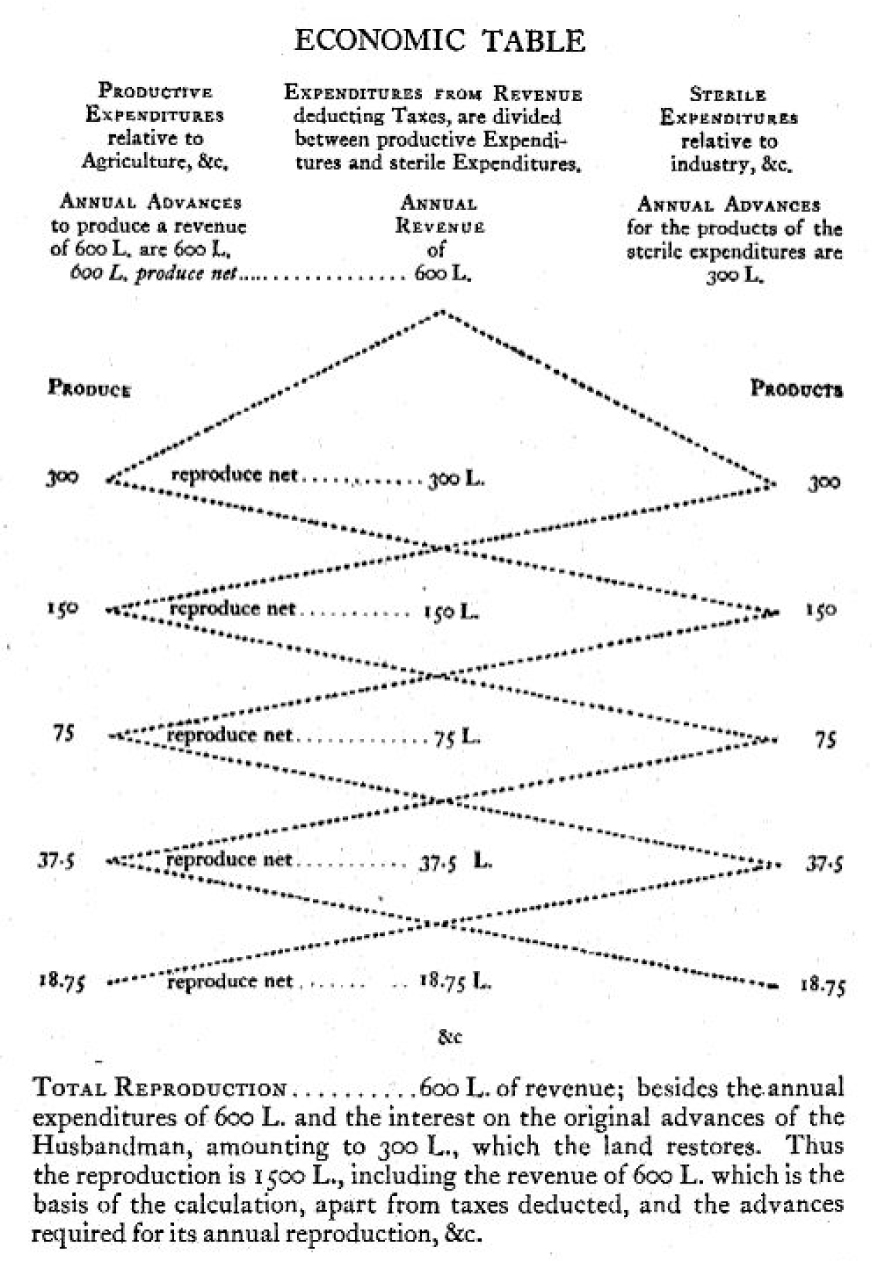

Quesnay, then, was first and foremost an economic activist. But he also enjoyed coming up with theories. His Tableau Economique attempts, in diagrammatic form, to show how money moves around an economy, just as blood moves around the body (see opposite).7 In a word, the Tableau shows how an economy works. A farmer (who remember, is the ultimate source of value in the economy) spends money, which goes into the hands of landlords and manufacturers. They then spend that money, some of which goes back to the farmer. What you end up getting is a circular flow of money around an economy. Putting it as a diagram was intended to make the whole thing intuitive.

Sounds simple? Despite Quesnay’s best efforts it remains exceedingly difficult to get your head around the Tableau. Vast academic papers have been written trying to explain exactly the point it is making, and few of them do a good job. It also does not include things like international trade, which makes it only a partial representation of an economy.

Despite its complexity the Tableau has proved influential. Schumpeter admitted that he struggled to understand it, but nonetheless ended up claiming that Quesnay was one of the four greatest economists of all time.8 Wassily Leontief, an economist who constructed accounts of the American economy in 1941, said he was following Quesnay.

A 1923 English translation of Quesnay’s Tableau Economique

Quesnay heavily influenced Marx, too, who referred to the Tableau as “incontestably the most brilliant idea for which political economy had up to then been responsible”. Marx ended up creating his own version (hence the “up to then” bit–Marx was not lacking in confidence). Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Count of Mirabeau, an early leader of the French Revolution and truly one of the world’s great suck-ups, claimed Quesnay’s Tableau to be one of the world’s three most important discoveries (the other two were the discovery of money and the invention of printing).

Why is the Tableau considered so influential? The fact that Marx liked it is surely one reason. Another possible explanation is its association with the “economic multiplier”, a core element of Keynesian economics. The naive version of the multiplier goes something like this: if someone spends a dollar, then someone receives a dollar. That person then spends that dollar, so it goes to someone else, who then spends it… and so on. A single dollar, therefore, can have far more than a dollar’s worth of value for society as a whole. This leads to the Keynesian policy recommendation that, during times of slow economic growth, the government can boost overall spending in the economy by loosening its purse strings. The “multiplier” means that the initial extra spending by the government ends up having a larger impact–by some “multiple”. Economists puzzle over how big the multiplier is: what seems clear is that the size of the multiplier varies according to country and time period.

A nascent form of the multiplier is evident in Quesnay’s Tableau Economique. Landlords, peasants and manufacturers–the only three classes in the economy–exchange commodities and money. These exchanges not only satisfy current needs, they also furnish all three classes with enough money in order to produce another round of exchanges the following year.9 Quesnay starts off assuming that there are 1,000 livres of money to spend (the livre was used in France from 781 to 1794). In one version of the tableau he assumes that the landlords spend that 1,000, split half and half between “productive” expenditure and “sterile” expenditure. That process continues, and the result, shows Walter Eltis, a historian, is that “a multiplier of two can be applied to the expenditure of rents”. (The multiplier changes, depending on the assumptions made about the apportionment of spending.) The point is that Quesnay was perhaps the first person to show clearly that spending begets other spending.

But that is not the biggest reason for the Tableau’s outsize influence. It represents a step forward in terms of how people thought about the economy.

The force of nature

Medieval economics had a very narrow focus. The primary purpose of all economic production was to enrich the monarch and, in turn, God. Taxes existed largely to buy the monarch robes and swans, rather than to provide public goods such as education or healthcare for the average Joe. Monarchs cared little about the living standards of their subjects, so long as revolution could be avoided. They regularly defrauded their own people to grab even more for themselves.

Quesnay’s Tableau, by contrast, showed that the world had reached an important turning point. A new conception of the economy, and of the appropriate role for government, had emerged. By drawing his diagram Quesnay is in effect saying, “there is something out there called ‘the economy’, which is subject to its own laws and can be analysed in its own right”.

This vision of the economy also had implications for the government. Its revenues were not simply a function of its tax policies; they depended on the performance of the economy as a whole. And the economy was not something that randomly spewed gold one year and then gave none the next. It was something that, with the right management, could spew gold every year. It was in the monarch’s interests to manage it prudently. Making his subjects richer would make him richer too.

What does “prudently” mean here? Here it is worth recalling that Quesnay was, first and foremost, a medical doctor. Doctor Quesnay believed that the economy was similar to the human body: sometimes it needed fixing, but whenever possible it should be left to do its own thing. It certainly should not be forced into an unnatural shape. Just as being obese is not healthy, neither is it healthy for an economy to be weighed down with taxes and regulations. “Physiocracy”, it is worth noting, literally means “rule by nature”.

Governments could ignore these “laws” if they wanted to. But they would pay the price in the form of worse economic performance. They could try to compel farmers, for instance, to provide food at below-market prices. But farmers would end up producing no food at all. Governments could slap taxes on trade between countries to try to raise tax revenue, but that would make the economy unhealthy, ultimately reducing overall tax revenues. The seductive logic of the Tableau Economique is that, to maximise overall efficiency, governments need to do as little as possible. “Let do and let pass, the world goes on by itself!” argues one of Quesnay’s disciples, Vincent de Gournay.

Not quite a zealot

Quesnay’s system of economic thought left room for some government intervention, but only the most basic sort. Just as a doctor might prescribe a diet of vegetables and exercise to a sickly patient, Quesnay thinks it a good idea that the government should build transport networks that will enable trade to take place more efficiently. “[W]ith a little reflection,” Dupont, one of Quesnay’s followers, asserts, “one can see with certitude that the sovereign laws of nature include the essential principles of the economic order.” Countless free-market economists were to make similar arguments in the years to come. The physiocrats’ views on agriculture were quickly discarded. Their seductive arguments about the benefits of a free-market economy were to prove far more enduring.