20

20

ALFRED MARSHALL (1842–1924)

An optimistic ending

He was the stereotype of the avuncular Cambridge don. His best pupil, John Maynard Keynes, recalled that from his study in a house close to the Backs, Alfred Marshall held “innumerable tête-à-têtes with pupils, who would be furnished as the afternoon wore on with a cup of tea and a slice of cake on an adjacent stool or shelf”. Marshall enjoyed strolling in the Alps–walking for a few hours, then sitting down on a glacier to have “a long pull at some book–Goethe or Hegel or Kant”, as his wife, Mary, put it. The legend went that when he was at St John’s College, he did his best thinking between 10am and 2pm, and 10pm and 2am.

Robert Heilbroner offers a memorable description: “Merely to look at Alfred Marshall’s portrait is already to see the stereotype of the teacher: white moustache, white wispy hair, kind bright eyes–an eminently professorial countenance.” Marshall founded the Cambridge economics department. A university education in economics, he reckoned, should involve “three years’ scientific training of the same character and on the same general lines as that given to physicists, to physiologists or engineers”. As well as being an influential university administrator Marshall’s published works exerted enormous influence over his students. Joan Robinson (1903–83), a contemporary of Keynes and a formidable economist in her own right, recalled that Marshall’s Principles of Economics, published in 1890, “was the Bible, and we knew little beyond it. Jevons, Cournot, even Ricardo, were figures in the footnotes… Marshall was economics”.

From that apparently unassailable position Marshall’s influence has waned. David Colander, an economist, writing in 1995, outlined received opinion: “Marshall is passé–at most a pedagogical stepping stone for undergraduate students, but otherwise quite irrelevant to modern economics.” Among economists it is generally agreed that Marshall did little more than sweep up pre-existing theories and put them into an easily digestible textbook form. So-called “real economists”, the thinking goes, study Léon Walras, who actually said novel stuff. Some writers have even expressed bafflement as to why Marshall was the most famous economist of his day. The theory runs that during Marshall’s time economics was going through some lean years; there were practically no good economists back then. “The relevant question,” writes one critic, “is not ‘Why Marshall?’ but ‘Who else?’”

Leave Alfred alone

That is unfair. Marshall more than deserved his fame. Yes, he did believe that his role involved systematising and improving the theories that had come before him. In that sense he had no pretensions that he was leading a revolution. Yet Marshall also introduced some entirely new economic theories. And like Jevons, Marshall recognised that incorporating mathematics would broaden the scope and precision of economic inquiry (he was an economist, not a writer on political economy).

Most important of all, Marshall was much more than a theorist. Like John Stuart Mill, Marshall put his intellectual efforts into improving society, especially for the poor. He was constantly thinking about how people in positions of political power could use his theories to influence government policy. But Marshall went beyond Mill in that he took empirical data extremely seriously, thus allowing him to go further in his policy recommendations. Marshall was an ivory-tower academic in the most glorious sense, but he was also deeply concerned for the downtrodden of Victorian and Edwardian England.

Alfred Marshall was born in 1842. His father, a cashier at the Bank of England, was a bit of a tyrant. He overworked his son, rather as John Stuart Mill’s father did him (though Alfred was at least allowed holidays). Like most of the people in this book, he was also a big nerd. When at school, a friend’s brother gave him a copy of Mill’s Logic–he would discuss it over dinner at the monitors’ table. For Alfred, mathematics was an escape: he very much liked that his father could not understand it. He was so good at maths, in fact, that in 1865 he was Second Wrangler at Cambridge–meaning that he was the person with the second-highest score in the maths exams. (John Strutt, who would win the 1904 Nobel Prize in physics, came top.)

Marshall began to earn a living teaching maths at the university–at which point he came across another of Mill’s books, Principles of Political Economy (1848). He spent many happy hours “translating his [Mill’s] doctrines into differential equations as far as they would go; and, as a rule, rejecting those which would not go”. He also glanced over Ricardo. Marshall took up a role as a lecturer in “moral sciences” (in effect, philosophy) in 1868, and from the early 1870s began to focus on economics.

Be celibate or get out

A few years later Marshall was involved in his greatest scandal. As he was giving lectures at the university, he came across Mary Paley, who was studying at the newly formed Newnham College. In 1877 they married–which forced them to leave Cambridge, since at that time fellows had to take a vow of celibacy. In leaving Cambridge, Marshall was taking a great risk with his career. By 1882, however, the rules on celibacy were changed and the couple were back. “In that first age of married society in Cambridge,” Keynes recalled, “several of the most notable Dons, particularly in the School of Moral Science, married students of Newnham.” By that point, too, Marshall and Paley were working together on academic projects. Keynes notes that Marshall’s father had “implanted [a] masterfulness towards womankind”, yet also acknowledged the “deep affection and admiration which he [Alfred] bore to his own wife”. (Paul Samuelson is less generous, finding that Alfred treated Mary “very badly”.)

The simplest interpretation of Marshall’s work is to see it as extending the thought of writers who had come before. As G. F. Shove, an economist, puts it, “the analytical backbone of Marshall’s Principles is nothing more or less than a completion and generalisation, by means of a mathematical apparatus, of Ricardo’s theory of value and distribution as expounded by J.S. Mill”. Who better than a Second Wrangler to put the theories of the great political economists into abstract mathematical language?

In this endeavour Marshall tried to clear up a number of confusions. Some bits of this work were more interesting than others. Historians have squabbled over how much Marshall was influenced by Jevons, for instance, without a great deal of progress being made. Marshall appears not to bother treating “price” and “value” separately, as most economists before him had done. Instead, like Jevons, he focuses just on price, which he sees as the same thing as value. But unlike with the popular understanding of Jevons’s theory, which emphasises that all that matters is how useful an object is, Marshall showed that the cost of producing something also influences its eventual price.

He also had some strong words for David Ricardo. Following Malthus, the classical political economist had argued that wages tended to reach a level which maintained workers at subsistence level–but no more. Any temporary increase in population would cause the working class to breed like rabbits, prompting the supply of labour to rise and wages to fall back down again. In the early 19th century this was just about a defensible viewpoint.1 Average real-wage growth per year during Ricardo’s adulthood was some 0.4%–pitiful, in other words.

By Marshall’s time things looked quite different. During his adult life real-wage growth per year was close to 1%.2 The average daily number of calories consumed by the average Briton increased each year twice as fast as it did during Ricardo’s time (by 1910 the average Briton was consuming around 3,000 calories a day, about what a young man needs, up from around 2,200 in the year in which Ricardo was born). Improvements in agriculture and industry had shown Ricardo’s theory to be invalid. “Our growing power over nature,” Marshall asserted, “makes her yield an ever larger surplus above necessaries; and this is not absorbed by an unlimited increase of the population.”

Marshall, in other words, did not share Ricardo’s pessimism. It turned out that wages did not always fall back to subsistence level. Instead Marshall argued that “the wages of every class of labour tend to be equal to the net product due to the additional labour of the marginal labourer of that class”–an explanation that corresponds closely with the modern theory of what determines wages. That underlay his fundamentally optimistic vision of society’s development. “The hope that poverty and ignorance may gradually be extinguished, derives indeed much support from the steady progress of the working classes during the nineteenth century,” he said in the 1890s.

Geography matters

That was not the only way in which Marshall changed economics. Geographers find in Marshall the first detailed exposition of what are today known as “economic clusters”. (As we saw in Chapter 4, Richard Cantillon had murmured on this phenomenon but no more than that.) Marshall referred to this as “an industry concentrated in certain localities”. Britain’s City of London financial district is a cluster, as is Silicon Valley–lots of similar businesses grouped together in a particular place. In his writings Marshall focused on the case of Sheffield, a big centre for the manufacture of cutlery. Marshall visited the city–“[b]lack but picturesque”, in his words–and toured the factories. It led him to ask the question, why do similar businesses group together?

On one reading of economic theory, it does not make sense. If companies instead decided to spread evenly across a country, they could reduce transport costs (Sheffield cutlery-makers had to incur hefty fees to supply, for example, Cornish consumers). But these downsides were outweighed by other factors. In clusters, Marshall argues, there was an “industrial atmosphere” conducive to higher productivity. As he put it, “the mysteries of the trade become no mysteries; but are as it were in the air, and children learn many of them unconsciously”. In other words, someone born and raised in Sheffield would acquire knowledge about cutlery, almost by osmosis. An industrial atmosphere was also conducive to innovation: “If one man starts a new idea, it is taken up by others and combined with suggestions of their own; and thus it becomes the source of further new ideas.” Marshall’s thinking on clusters was to become immensely influential in the late 20th century, in particular with the work of Michael Porter.

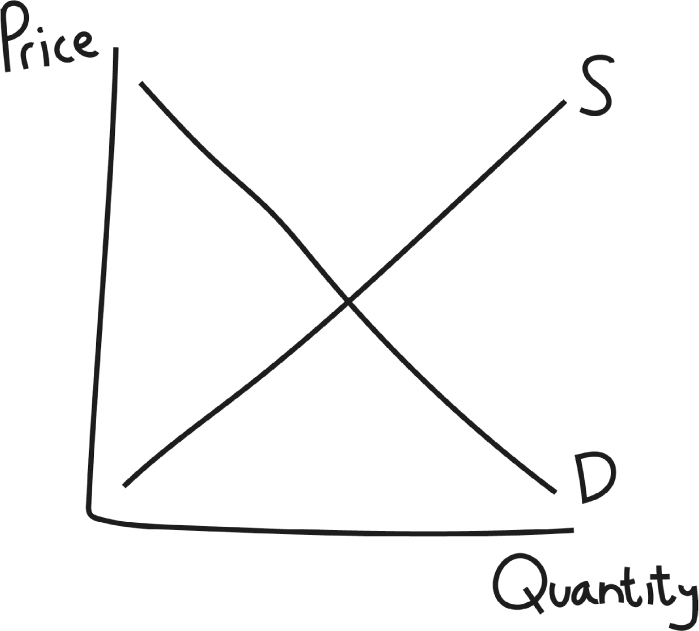

Keynes also attributes all sorts of other economic concepts to Marshall. One is the tricky statistical idea of “chain-linking”, which today is used by statistical offices all around the world to construct measures of inflation (among other things). Another is “purchasing-power parity”, which refers to the notion that some countries are cheaper to live in than others. And last but not least, Keynes argues that “I do not think that Marshall did economists any greater service than by the explicit introduction of the idea of ‘elasticity’,” the notion that changes in the price of things will lead to disproportionate changes in demand or supply for those things. And that is before you get to the most recognisable motif in economics, shown below: the supply-and-demand diagram. In fact, the famous chart is often called the “Marshallian cross diagram”.

Debate has raged over whether Marshall truly is the “creator” of such a curve.3 Keynes called Marshall the “founder of modern diagrammatic economics”. The Economist has argued that “Marshall’s book established the use of diagrams to illustrate economic phenomena, inventing the demand and supply curves familiar to fledgling economists ever since.”

Historians quibble. Joseph Schumpeter criticised the “uncritical habit of attributing to Marshall what should, in the ‘objective’ sense, be attributed to others (even the ‘Marshallian’ demand curve!).” In a detailed study Thomas Humphrey notes that at least five economists, including Auguste Cournot, used the cross diagram before Marshall. Nonetheless, the diagram probably does deserve the adjective “Marshallian” because, in Humphrey’s words, Marshall “gave it its most complete, systematic, and persuasive statement”. Even Schumpeter admitted that “practically all the useful ones [graphs] we owe to Marshall.”

In sum, Marshall’s contribution amounts to more than just the words of the classical political economists, tarted up with mathematical theories and diagrams. He had lots of interesting ideas of his own. But even that is not Marshall’s true contribution to economics. He turned the discipline from a pessimistic, arrogant subject into one that was more sceptical and pragmatic.

Consider the context in which Marshall was writing. In the mid-19th century political economy fell into disrepute. Ricardo’s horribly pessimistic viewpoint had helped give political economy the moniker “dismal science”, which has stuck to this day. Charles Dickens published Hard Times in 1854, featuring the relentlessly utilitarian and unfeeling Gradgrind. Only bankers were held in lower regard than political economists. In the mid-1870s Walter Bagehot, to commemorate the 100th birthday of the Wealth of Nations, wrote a rather gloomy essay on political economy. Not one for sentimentality, he reported that the subject “lies rather dead in the public mind. Not only does it not exert the same influence as formerly, but there is not exactly the same confidence in it.” John Stuart Mill was probably the only economist of any eminence, and in certain circles he was a laughing stock.

So the new crop of economic thinkers could hardly just tweak what their forefathers had written and hope for the best. And Marshall did not do that. It is hardly a surprise that, like Jevons, he jettisoned the term “political economy” and chose “economics” instead. Like Jevons, he recognised the benefits that the incorporation of mathematics could bring to economics. Marshall was not able to use the complex statistical tools, such as regressions,4 available to economists today, though he surely would have done.5 But mathematical habit, he said, “compelled a more careful analysis of all the leading conceptions of economics”.

Yet unlike Jevons, Marshall was not a maths nutter. Yes, in many instances maths would help people think more clearly, he believed. On the other hand, he worried that throwing in lots of equations was hardly going to make the general public look upon the discipline more favourably. Open a copy of Marshall’s Principles and the layout looks odd. The equations are relegated to footnotes at the bottom of the page. Marshall knew that ordinary people would not buy his book if they saw it was stuffed with algebra.

Especially as he got older, Marshall started to take a more principled objection to the use of abstract mathematics in economics. He became more interested in understanding the real world. What pushed him in this direction is unclear. It may have been because of the purple patch that biology–the least mathsy of all the natural sciences–was enjoying at Cambridge at the time.6 Charles Darwin had published On the Origin of Species the year after Marshall had become a lecturer at Cambridge. “The Mecca of the economist is economic biology rather than economic dynamics,” Marshall wrote in 1898.

Whatever the reason, over time Marshall became more and more interested in data about the real world, and less interested in theorising. Marshall read plenty of history. “I had some light literature always by my side,” he once said, “and in the breaks I read through more than once nearly the whole of Shakespeare, Boswell’s Life of Johnson, the Agamemnon of Aeschylus.” (Light literature?!) He looked at Karl Marx, and came to accept the historical contingency of economics–what might be true in one time and place might not be true in another. Marshall also vowed to do more to understand the culture and history of his own country, rather than simply relying on data tables. In 1885 he went on a long tour of England, which he thoroughly enjoyed. In Preston he stayed in the “most beautiful hotel we have seen”, and was impressed by the abstemiousness of the residents of Blackpool.

Marshall’s course of self-education changed his outlook on the world. He came to believe that the earlier crop of political economists had been naive in their theorising. Ricardo had proposed “iron laws” of economics, not just on wages but on questions of value, trade and economic development. Marshall himself believed that the “chief fault in English economists at the beginning of the century was that they regarded man as so to speak a constant quantity, and gave themselves little trouble to study his variations”.

That realisation encouraged Marshall to take a new approach to economics. To put it into slightly pretentious language, Marshall became more inclined to rely on a posteriori knowledge–ie, from experience–than a priori knowledge–ie, from pure logic.7 Over time he moved further away from his earlier Jevonian fascination with maths.8 In his early sixties Marshall had an unforgettable line when it came to the use of mathematics, which is worth repeating in full:

I had a growing feeling in the later years of my work at the subject that a good mathematical theorem dealing with economic hypotheses was very unlikely to be good economics: and I went more and more on the rules. (1) Use mathematics as a shorthand language, rather than as an engine of inquiry. (2) Keep to them till you have done. (3) Translate into English. (4) Then illustrate by examples that are important in real life. (5) Burn the mathematics.9

Jacob Viner commented that “non-mathematical economists with an inferiority complex–which today includes, I feel certain, very nearly all non-mathematical economists–may be pardoned, perhaps, if they derive a modest measure of unsanctified joy from the spectacle of the great Marshall, a pioneer in mathematical economics himself, disparaging the use of mathematics in economics.” But Marshall was keen not to dispense with theory altogether and rely solely on lived experience. “The most reckless and treacherous of all theorists is he who professes to let facts and figures speak for themselves,” he said. All observation is unavoidably theory-laden. Marshall’s Principles is an exemplary combination of principles and data. In it he expounds on theories at great length, but there is also data on everything from the population of different cities to an estimate of the “wealth of the British empire in 1903”.

What is it good for?

Marshall did not become an economist merely in order to be a successful academic, though he was that. He had a very practical objective in mind. He saw himself as someone who would help governments devise good policy. As Jacob Viner puts it, Marshall was “a Victorian ‘liberal’ in his general orientation toward social problems”. The latter part of the 19th century was one in which politicians, for the first time ever, became genuinely interested in devising good policy. With nearly complete adult male suffrage in Britain in 1867, both political parties had little choice but to court the votes of the working classes. “Social reform through legislation thereafter became respectable political doctrine for both parties,” says Viner. This was the era of Charles Booth and of Seebohm Rowntree. And Marshall was right at the centre of this new debate.

He advised the government on higher education policy and was also involved in debates over tariff reform in the early 1900s. In 1903 Marshall published the Memorandum on Fiscal Policy of International Trade, which began life as a memo for the chancellor arguing in favour of free trade. T. W. Hutchison refers to it as “one of the finest policy documents ever written by an academic economist”.

Above all else Marshall wanted to reduce poverty. He only had to look around him to see that there were plenty of people who still needed help. Despite Britain being 150 years into the industrial revolution, and real wages rising smartly, grinding poverty continued. The political economists–in particular, Ricardo, Malthus and the early Mill–had basically believed that the working classes were destined to live at subsistence level. Efforts to raise their standard of living could even do more harm than good, the thinking went. Marshall, by contrast, had no time for such a lack of ambition. The “end of all production”, as Marshall saw it, was to “raise the tone of human life”, but he believed that up to that point “the bearing of economics on the higher wellbeing of man [had] been overlooked”.

Once, Marshall walked past the window of an art gallery. In the window was a painting of a “down-and-out”, as he put it. He bought the painting at once. “I set it up above the chimney-piece in my room in college and thenceforward called it my patron saint, and devoted myself to trying to fit men like that for heaven.” At the beginning of Principles he pronounced that the purpose of “economic studies” was to ensure that “all should start in the world with a fair chance of leading a cultured life, free from the pains of poverty and the stagnating influences of excessive mechanical toil”.

Eat your greens

At times Marshall’s concern for the poor sounds very Victorian. He intersperses his discussion of economic theory with sanctimonious moralising.10 He considered that some people, the “Residuum”, were “morally incapable of doing a good day’s work with which to earn a good day’s wage”. Parents who did not raise their children appropriately needed to be punished: “The homes might be closed or regulated with some limitation of the freedom of the parents.” As Stigler put it, Marshall believed that “[t]he proper route to the elimination of poverty [was] to educate (in the broadest sense) the unskilled and inefficient workers out of existence.”

But look past the preaching. Marshall believes that policy can help too. This was a step forward from the earlier classical economists, whose only recommendation to the poor was to have fewer children or to pay a visit to a workhouse. Marshall’s instincts, in fact, were socialist. “The world owes much to the socialists,” he stated in a Presidential Address to the Economic Science and Statistics Section of the British Association in 1890, “and many a generous heart has been made more generous by reading their poetic aspirations.” He was to confess that “I was a Socialist before I knew anything of economics.” He believed that the rich squandered their over-large incomes on stuff that was not really of use to them. Overall societal welfare would be much higher if the poor were given more spending power. As he argued, a “vast increase of happiness and elevation of life might be attained if those forms of expenditure which serve no high purpose could be curtailed, and the resources thus set free could be applied for the welfare of the less prosperous members of the working classes”.

Despite this, Marshall the economist was in no way a socialist. Like liberals today, he argued that competition under capitalism was a good thing. He believed that relying on free markets made a lot more sense than relying on the whims of government bureaucrats. As he put it, “experience shows creative ideas and experiments in business technique, and in business organisation, to be very rare in Governmental undertakings.” Marshall had little time for those on the left–most notably Marx–who saw capitalism as consisting only in “the exploiting of labour by capital, of the poor by the wealthy”, and who refused to acknowledge the benefits of the “constant experiment [by] the ablest” in management and entrepreneurship. And of course, he acknowledged time and again the enormous increases in living standards that had taken place in recent decades. So to conclude that Marshall was “a socialist” would not be quite right.

But Marshall did want reform–and substantial reform at that. He recommended higher taxes on the very richest. Modern readers will be unsurprised at that. Anthony Atkinson, an expert on inequality, showed that in the early 20th century, Britain’s top marginal rate of income tax was just 8% (as of 2020 it is 45%). Marshall also thought, like Mill, that it was a good idea to tax inheritances more heavily. Contrary to many of the theorists in this book, such as Condorcet, Marshall had little time for the notion that someone had a “right” to inherit money that they had not earned.

Marshall also favoured more direct means to improve the lot of Britain’s poorest. He was not a full-throated supporter of trade unions in the manner of John Stuart Mill (he may have worried that trade unions were growing too quickly, a reasonable concern: from 1890 to 1920 the share of workers in a trade union rose from 10% to nearly 40%). But he saw that they could serve some useful purpose in providing benefits and security to workers. After all, he clearly recognised the uneven bargaining power which low-skilled workers faced when looking for a job. Sounding almost like Marx, Marshall argued that “when any group of them [unskilled labourers] suspends work, there are large numbers who are capable of filling their place”. Marshall was also interested in the possibility of introducing a minimum wage “fixed by authority of Government below which no man may work”. Theodore Levitt, an economist, in fact shows that Marshall had loads of other ideas for improving capitalism, from smart regulation of large companies to protecting consumer rights. With Marshall we see the stirrings of a programme of liberal social reform that was to take hold over the subsequent half-century.

The end of the line

Marshall is perhaps the strongest bridge between the man who has the best claim to have invented economics, Sir William Petty, and the modern discipline that is so influential today. After Petty’s “political arithmetic” there were 150 years or so of mostly abstract theorising. The classical political economists tried to cram everything they knew into a beautiful, overarching theory that would, in time, benefit from formal mathematical analysis. Marshall, despite being the best mathematician in this book, steered economics back towards its empiricist roots.

Bagehot had remarked in 1876 that political economy “lies rather dead in the public mind”. People were fed up with complex theories that treated humans like automatons and which suggested that a sustained improvement in living standards was impossible. Marshall came along and offered a more positive story. Economists could, he said, help to effect positive social change. They just had to get their hands dirty. “[O]nce Marshall had become the leading British economist”, says Jacob Viner, it was no longer “a common charge against economics that… all that it asked of men ‘is that they should harden their hearts’… the question of whether humane men could be devotees of the dismal science had ceased to be a live one”.

What we see in Marshall is an imprecision, a vagueness, a diffidence–which while less impressive than the abstraction of, say, David Ricardo, feels a lot more modern. He perceived that economic theories were never set in stone, a conclusion that has been resoundingly borne out by what has happened in the economics profession since he died.11 He was a cautious thinker who recognised that to improve the world, economists often had to settle for second-best solutions and imprecise conclusions. In Keynes’s words, Marshall had built “not a body of concrete truth, but an engine for the discovery of concrete truth”. He was, in a word, a very modern economist.