THE CALIFORNIA SUN wakes me up after only three hours. I squeeze my eyes shut and bury my head in my arms. I had that dream about Alex again, the one I’ve had several nights in a row. We’re at a costume party and he pretends he doesn’t know me, even when I take off my elaborate feathery mask. My mouth is dry, my jaw hurts, and I’m sweating through my T-shirt. I unzip the sleeping bag and stretch out on top of it, hoping I can get at least another hour, but it’s no use.

The apartment is wide-awake, flooded with buttery mid-morning sunshine. Outside birds are singing, a truck beeps as it backs up, a leaf blower roars, and someone coaches her dog to go potty in baby talk. The Backstage lays disheveled and exposed next to me like a one-night stand, the kind I’ve only seen in movies. I push it aside, sit up, and rub my eyes.

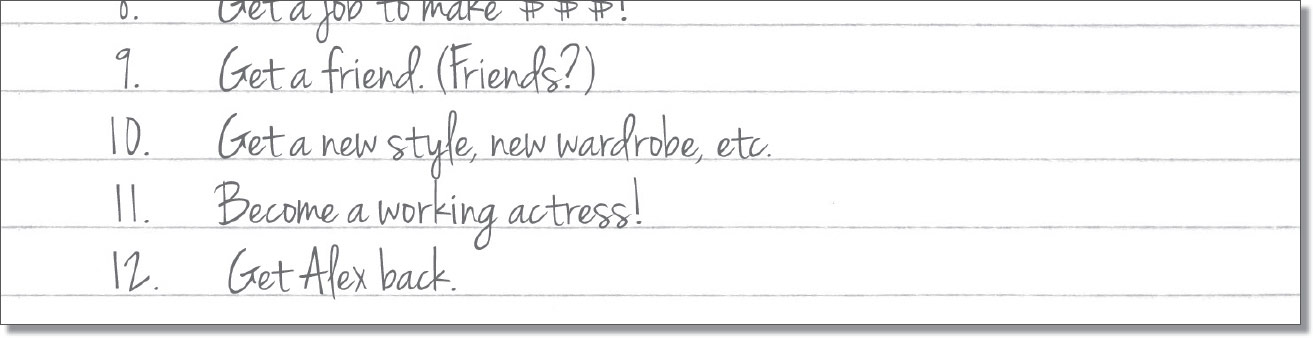

The day in front of me seems gaping and enormous. I think about my friends—and of course Alex—starting college. They probably have orientations and class schedules and planned-out days. They’re decorating dorm rooms and becoming instant best friends with their roommates. I wish someone would orient me, but I’m going to have to do it myself. Mom once told me that happiness can be as simple as creating goals. The important thing is to keep them realistic and achievable. I grab my notebook, prop myself against the wall, and start my list.

The list veers so quickly out of the realm of the realistically achievable that I feel nauseous, but before I can stop myself I have to add one more thing.

My autonomic nervous system is about to accelerate into full panic when there’s a knock at my door. I tense up and lean forward. Who is it? The Scientologists? The landlord? Raj? The knocker knocks again, this time a little more firmly. I leap to my feet and pull on my jeans. Maybe it’s 1-800-GET-A-BED, running ahead of schedule.

“Hello?” I ask from behind the safety of the locked door.

“Hi,” a girl’s voice answers.

With the chain still fastened, I open the door a crack and peek outside. Standing there is a girl with brown eyes as big as a cartoon princess’s. Her dark hair falls around her shoulders in loose, fresh-from-the-beach curls. She’s wearing a short white dress and cowboy boots.

“I’m Marisol,” she says. “I live in number nine. I need some help.”

“I’m Becca,” I say, unlocking the chain and opening the door. “What’s wrong?”

“You are not going to believe this shit, but I just locked myself out of my apartment. And literally seconds later, I started my period. I have an audition in exactly twenty-eight minutes in…Wait for it.” She holds up her hand and purses her lips. “Culver City.”

“Oh my God,” I say, though I have no idea where Culver City is.

“I know, right? I have about five more seconds before I ruin my dress and ten seconds until I’m officially late. If I could have a tampon and use your bathroom, I will love you for life.”

“Oh, sure. Come on in,” I say, feeling a little self-conscious as I gesture for her to enter. “It’s a little, um, rustic. I just moved in.”

“Girl, is that where you sleep?” she asks, pointing to my sleeping bag with one hand as she holds her dress away from herself with the other.

“Kind of,” I say. “I just got here yesterday.” I dig through my suitcase until I find the crushed box of tampons that’s traveled with me all the way from Boston. “I didn’t exactly sleep last night. It’s more…where I lie down.” Marisol throws her head back in a genuine laugh, and I feel myself relax. “Take as many as you need.” I present her with a fistful of tampons. “Take them all!”

“I only need a couple,” she says, plucking two from the bunch. She tiptoes over my strewn belongings to the bathroom. The air she’s passed through buzzes with energy and the scent of hair product. She’s going to be my friend. I can just feel it.

“Dude,” she says as she shuts the door. “This shower situation is hard-core. The garbage bag and the duct tape…?”

“I only brought one suitcase,” I say, wondering if she thinks I’m some kind of psycho. Seconds later, I hear her running the water and wish I’d bought hand soap at the Mayfair instead of just the bar of travel-size Dove. At least there’s toilet paper, I think, even if it is painfully cheap. Literally. “And I don’t have a car, so I just had to grab what I could from the Mayfair and make the best of it.”

“No car?” she asks, emerging from the bathroom and flicking the excess water from her hands. I shake my head no. Some mixture of surprise and horror darts across her face before she assumes a neutral expression and says, “That’s probably for the best since there’s no parking here at the Chateau Bronson.” She casts her eyes around the apartment. “But somehow, someway, you need to make an Ikea run stat. I’d take you myself, but I won’t be back until tonight.”

“That’s okay. I can take the bus.”

“How are you going to get the stuff back?”

“A cab?”

“That will cost a fortune! Just wait. I can do it on Friday if you want. I’m free.” She glances in the vanity mirror, scrunches her hair, and swipes on orange lipstick. If I wore that color, people would think I’d lost my mind, but Marisol looks chic as she smiles in the mirror.

“What’s your audition for?”

“Dog food,” she says, swinging her purse over her shoulder and heading for the door. “That’s right, I’m getting all dolled up for one line in a dog food commercial. Just what my grandma dreamed of when she swam here from Cuba.”

“Your grandma swam from Cuba?”

“I’m teasing,” Marisol said. “She had a raft. Anyway, knock on my door tomorrow. I’ll show you my place.”

“You bet,” I say, blushing because I sound just like my mom. I watch Marisol skip down the stairs to her own little rhythm. I go back inside the apartment, pick up my list, and put a faint but hopeful check next to number nine.

After Marisol’s exit, my apartment swells with emptiness. Seeing the place through someone else’s eyes makes me realize how much I have to do to make it livable. I take in the wooden floor, which seems to have acquired another layer of dust in just a few hours, the sleeping bag, the suitcase and rumpled clothes, the open Backstage, the paper shopping bag / trash can from the Mayfair, and of course, the refrigerator. I snap a few pictures with my phone. I left the camera that my mom gave me on the front seat of Alex’s car. As soon as he calls I’m going to ask him to send it. But I couldn’t post those pictures online anyway, and right now that’s what I want to do. I’ll need to capture the “before” of this place so my mom and my forty-nine followers on Instagram can truly appreciate the “after.”

The despair of the apartment catches up with me, and I remember the day I found out I’d been rejected from Juilliard. I’d been holding out hope for my last possibility. It was the only school I hadn’t heard from yet. The letter was late, which I knew was sometimes a good sign. I’d been waiting all day for the mail to arrive and was distracting myself by applying a homemade beauty mask. I watched the clock on the microwave turn to 3:00 p.m. as the avocado-and-cucumber mixture stiffened uncomfortably on my cheeks. Mom was upstairs doing laundry. She’d worked the weekend and had the day off. I was beginning to think the mailman had forgotten us until I heard the sound of the next-door neighbor’s dogs barking. I peeked out the window and there he was, coming up the driveway, his bag possibly containing the key to my future. I froze, my heart pounding in my teeth. Seconds later a thick bundle dropped through the mail slot and landed on the kitchen floor.

I knelt down and tossed the Pennysaver, the bills, and the triplicate copies of the Pottery Barn catalog aside. There it was. The envelope I’d been waiting for, with the return address printed in the distinctive navy-blue font. My fingers were shaking as I ripped it open and pulled out the letter.

We regret to inform…Unfortunately…Highly competitive…Record number…Talented pool…Wish you luck…

A glop of mask dropped onto the paper, and a scream, high and pure, escaped my lungs.

“Becca?” Mom called from upstairs. “Are you okay?”

I sank to the tile floor. Mom’s footsteps pounded down the stairs as I sat up and reached for an Easter-themed dish towel.

“Jesus H. Christ, what is on your face?” Mom asked.

“A mask,” I said, and handed her the letter. I felt my face crumble again as I wiped the goop from it. “I’m not going to Juilliard.”

Mom put a hand to her heart and let out one of her quiet, breathy gasps. “I’m so sorry. I’m so, so sorry.”

My mother’s sympathetic voice unleashed another wave of tears, and she pulled me in for a hug even though she was wearing an ivory-colored sweater. We sat like that, hugging, Mom stroking my back in even circles until I finally caught my breath.

“It’s official,” I said. “I didn’t get into college.”

“How did this happen?” Mom asked quietly. Then she pursed her lips and, sitting across from me, wiped the places I’d missed: my hairline, my nose, my jaw. She was focused and calm, but I could see her mind working like the gears of a clock.

“Mom?” She steadied my chin with her hand and wiped my eyebrows. “Say something.”

“I’m just…”

“Just what? Say it.”

“I’m not sure what we’re going to do.”

I wanted comfort and reassurance. I wanted her to tell me this was going to be fine, that it was perfectly normal or that we were going to turn it all around. I wanted her to say, “In five years, will you even remember this?” like she had that time Brooke Ashworth was cast as Ophelia when I knew I’d done a better job in the audition, or when I’d gotten a C on the chemistry final.

“What now?” I asked. “Mom?”

“I don’t know,” she said as if I weren’t her baby or her little girl, but a full-blown adult. Just like her. “I really don’t know.”

The whining fridge brings me back to the moment. I’m suddenly ravenous. Luckily, I bought that container of yogurt early this morning. The only problem is that I don’t have a spoon. I fashion the lid of the yogurt container into a scooping mechanism that looks promising. With no chairs, I sit on the floor under the window and try to eat, but it’s not working. I wash my hands with the travel-size Dove, abandon the yogurt lid, and use my fingers to eat it over the sink. I’m an animal, I think, a human-animal. I’m glad that no one can see me until I notice that a lady in the apartment across the street, an old woman in a bathrobe, is watching me. She tilts her head in what I think is curiosity.

“I don’t have a spoon,” I say aloud even though I know she can’t hear me. I look at her and shrug in an exaggerated way. She shuts her curtains. Raj told me he lived in number seven if I needed anything. Well, I think to myself as I wipe the yogurt off my face, I do need something. A fucking spoon.

“Hi!” I say when he opens the door, a coffee mug in hand. I could be wrong, but his eyes light up a little when they see me. “Come on in,” he says. “Becky, right?”

“Becca,” I say, stepping inside. “I’m actually wondering if I could borrow a spoon?”

His apartment is spare and well organized. It has the same basic setup as mine, but actually looks like someone’s home. A neat someone’s home. His bed is made with crisp, folded corners. No clothes on the floor. No piles of papers. I bet I could open any drawer or cupboard at random and everything inside of it would be lined up, purposefully arranged, just so. There are several bookshelves, one dedicated entirely to titles about movies, and another filled with books about everything, from architecture to American history to classic literature. One corner of the room, with a large L-shaped desk and a huge, pristine desktop computer, is clearly what he uses as his office.

“Your place is really nice,” I say.

“Thanks,” he says.

I smell fresh coffee, and my mouth begins to water. My hunger had hardly been satiated by the yogurt. I have to stop myself from running toward the scent.

“You, ah, want some coffee?” he asks, one corner of his mouth turning up in a grin.

“Was I that obvious?” I pull my hair back into a ponytail and tie it with the elastic that’s been around my wrist all night, leaving a red indentation.

“Let’s just say that you look like you could use some coffee. I only made enough for one, but I can brew another pot,” Raj says, leading me to the kitchen nook, where two chairs are tucked under a little table. He hands me a plate with a warm piece of buttered toast on it.

“Thanks,” I say, and take a seat at his kitchen table. I eat the delicious toast in four bites as he scoops coffee into the filter. There are three screenwriting books on the table, all of them marked with color-coded Post-its. “So, you’re a screenwriter?”

“I’m more of a director, but I write some, too. And there’s this screenwriting competition at my school that’s coming up. The winner gets a hundred-thousand-dollar grant to make a movie.”

“A hundred thousand dollars? Wow.”

“I know. And I have this idea that I think is promising, and I really want to win, but there’s not a lot of time.”

“When’s the deadline?”

“December first,” Raj says. “Coming right up.”

“That’s ages away,” I say, thinking of my own promised college deadlines. “You can totally make that.”

“It takes a while to construct a really good screenplay. It’s all in the planning,” he says.

“What do you have to plan?” I ask. I know a lot about putting on a play because I’ve been in so many, but I guess I’ve never thought that much about what goes into making a movie. They just seem to tumble into the world fully formed, though of course I realize that’s not how it works. “Do you outline, like a term paper?”

“Definitely. But I’m nowhere near the outlining phase.” He takes in my confused expression. “I’d like to have a logline by the end of the day and a beat sheet by the end of the week.”

I don’t really know what any of these things are, but I nod as if I do.

“You’ll do it,” I say. “I believe in you.”

“Thanks,” he says. The coffee pot sputters, indicating it’s ready. He smiles as he pours me a mug. “Anyway, how was that nap?”

“I don’t have a bed yet, so I was on the floor…so, not great.”

“No bed? No spoon?”

“No nothing,” I say. As he hands me the coffee, I feel for the briefest second like I might cry. I bring it to my lips and after a few sips, the hot liquid seems to zip through my veins. I’ve never been a coffee drinker, but I become one in this moment. “Oh my God. This is so good! This is like the best coffee I’ve ever had.”

He smiles again, this time with his whole face.

“What?” I ask.

“You’re just very enthusiastic. Where are you from?”

“Boston,” I say as he butters more toast and hands me another piece. I devour it. He laughs. “What now?”

“Nothing,” he says, smiling and shaking his head.

“Do you know how to get to Ikea?” I ask.

“In Burbank?”

“I guess?”

“Take Western to Los Feliz to the Five.”

“Can I do that on a bus?”

“You’re going to take a bus to Burbank?”

“Is that so crazy?” I ask. “I could take a cab back.”

“A bus from Hollywood to Burbank?” he says, topping off my coffee. “Actually. Yes. It’s crazy. You need a car.”

“That’s what everyone keeps saying, but there have to be people who live here without a car. I mean, what am I supposed to do? I can’t buy a car until I get a job. And I can’t get a job until I stop living like a human-animal. And I can’t stop living like a human-animal until I get some furniture and a spoon. But I can’t get furniture until I get a car. But I don’t drive. So that puts me back at the beginning.”

“It really is a vicious cycle, isn’t it?” Raj says.

“Yes, it is,” I say. “I used a sweatshirt stuffed inside another sweatshirt as a pillow last night.”

“Tell you what. I don’t have to be at work until four. I’ll take you to Ikea.”

“Really? You’d do that for me?”

“For the most enthusiastic human-animal I’ve ever met? Sure,” he says, grabbing his keys off a hook.

“What about your logline?”

He hesitates. “Eh, I’ll do it tonight.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, but we have to leave now so we can beat the traffic home. Can you do that?”

“Let me check,” I say, and scroll through an imaginary calendar in my mind. “What do you know? I’m free.”