The drawing into the workforce of immigrants (the global reserve army of labor), particularly in lower-paid jobs in the last thirty years or so, like the absorption of women with children into wage labor that accelerated in the 1950s, is a consequence of the process of expanded reproduction or accumulation in the United States and abroad, on the one hand, and the consequent dispossession abroad, on the other.1 Here most immigrant workers join many native-born African American, Latino, and women workers in the lower-paid ranks of the workforce, where often productivity is lower and more labor required. Both foreign and domestically born Blacks, Asians, and Latinos composed over a third of the US population in 2010, compared to 20 percent in 1980, with the Latino and, on a smaller scale, Asian populations growing fast due to immigration.2

These racial and ethnic groups now make up a large and growing proportion of working-class occupations. Blacks, Latinos, and Asians, including immigrants, composed about 15–16 percent of the workers in production, transportation, and material moving occupations as well as in service occupations in 1981 and now make up close to 40 percent of each of these broad occupational groups. Furthermore, these groups are spread throughout these occupational categories to a much larger degree than in the past. In construction trades, for example, workers of color composed 37 percent in 2010, compared to 15–16 percent in 1981. Below we will see that Blacks, Asians, and Latinos together composed about 35 percent of the employed working class, compared to 22 percent for the middle class and 11 percent for the capitalist class.3 It is also the case that these groups of workers are disproportionately concentrated in urban areas. As shown below, they are central to the logistics clusters, with African Americans making up almost half of the warehouse workforce in the Chicago area and Latinos likewise in the Los Angeles and New York–New Jersey clusters, as well as to the commodified labor of social reproduction and capital maintenance.

To a certain extent, these increases in the proportion of workers of color have been reflected in the unions. In terms of union density, the percentage of workers in employment who belong to unions, men, women, and every racial and ethnic group lost ground after the early 1980s. Yet among those who do join unions it is women, Blacks, Latinos, and Asians who are more likely to win an NLRB representation election, thus bringing growth. Women, women of color in particular, are more likely to become union members than any other group.4 Women now compose 46 percent of all union members. The proportion of Blacks, Asians, and Latinos in union membership also rose from about 23 percent in 1994 to 33 percent in 2014, about 13 percent of total membership being immigrants.5 While Blacks are more likely to be union members than white workers, the biggest growth, after women in general, has been among Latinos, many of them immigrants. Between 2011 and 2014 alone some two hundred thousand Latino workers joined unions. While the rate of unionization among foreign-born workers who are not citizens is only half the national rate of 12 percent, for those who are citizens it is 13 percent. Furthermore, the longer immigrant workers are in the United States, the higher the rate of unionization, eventually surpassing the rate among whites and pointing toward large-scale future growth among the foreign-born.6

To some extent this rapid growth in unionization among immigrants and Latinos probably reflects the growing activism in the Latino community, much of it around immigrants’ rights and organization. Asians and Pacific Islanders, however, also saw a leap in union membership by ninety-six thousand in one year from 2013 to 2014.7 Black workers have remained about 13–15 percent of union membership since the early 1980s and unable to increase as a proportion largely due to the loss of manufacturing jobs that hit African American communities particularly hard. Yet in the last decade or so there has been an increase in community-based Black worker organization and more recently mobilizations around the Black Lives Matter movement. It seems likely that just as activism in the Latino community contributed to increased union membership, this new Black activism may also lead to a growth in union membership and organization among Black workers.8

It seems clear that these workers are central to organizing in areas such as warehousing, hotels, hospitals, building services, meatpacking, and others where they form a growing proportion of the workforce—indeed, those sections of the workforce that are actually growing. For such organizing to be successful, however, it must address the enormous inequalities within the working class as well as those in society in general. To argue that today’s working class is far more diverse than that of three or so decades ago is not to say that inequalities of gender and race have disappeared. Even for full-time workers median weekly earnings differ by gender and race. As of 2010, male full-time workers earned $824 a week, compared to $669 for women. Whites took home $765 a week in wages, compared to $611 for African Americans and $535 for Latinos.9 In 2011, 23.4 percent of white workers’ earnings were below the poverty line, while 36 percent of Blacks and 43.3 percent of Latinos fell below that line. The difference between men and women was 24.3 percent.10 Race and gender lines remain major fault lines in the structure of the changing working class.

While many unions have made efforts to incorporate more workers of color, immigrants in particular, the perpetuation of business union norms and institutions continue to make it difficult to confront racism in the ranks and in society. A focus on organizing these low-paid industries and occupations can begin to address this, but internal challenges will also be needed to transform “diversity” into interracial unity.

Today’s working class does not look like that of half a century ago. Using Hal Draper’s representation of the working class as concentric circles from an industrial “core” to outer rings of workers presumably less concentrated or less likely to be direct producers of surplus value, we can see the differences from the beginning of the era of transition in the 1980s.11 The employed working-class private industrial core, consisting of production and nonsupervisory workers in mining, manufacturing, construction, utilities, transportation and warehousing, and information numbered 22.9 million in 2007 before the impact of the Great Recession, compared to 20.2 million in 1983. In relative terms, of course, it has shrunk. This industrial core accounted for 24.3 percent of the total production and nonsupervisory workforce in 2007, down from 33.2 percent in 1983.

Furthermore, the composition of the core has also changed with the number of mine, mill, and factory workers shrinking from 64 percent in 1983 to 47 percent of the core in 2007. On the other hand, those in transportation and warehousing, at the center of logistics, whose numbers grew by 68 percent over this period, increased from 12 percent to 17 percent of the core, while those in the information sector increased by over half, rising to 11 percent of the core.12 As we shall see, logistics workers are part of the overall production process of goods output, including even that of many imports. It is fair to say that these logistics workers have at least as much leverage in the economy of today as autoworkers did in the 1970s. Naturally, the Great Recession had a severe impact on manufacturing in particular, so that the core shrank to 20 percent of the private workforce. The degree to which it grows again remains to be seen.

In the minds of many this core is the domain of the white male worker. Gender segregation in employment, like that of race, is, of course, still a reality, and the majority of women workers, now almost half the workforce, are found in service, sales, and office work. But the proportions have changed. In 2010 in manufacturing, women composed 28 percent of the core workforce. In transportation and warehousing, women are almost a quarter of the workforce, while in utilities they are 22 percent of the workforce. Construction has the smallest percentage at only 9 percent. On the other hand, women compose 41 percent of the information sector. If construction is excluded, women are almost a third of the core. Together with minority workers, even allowing for considerable overlap, nonwhite male workers probably account for about 40 percent of the core and are certainly likely to increase in the coming decade or so.

At the same time, as we will see below, millions of workers beyond the traditional core are employed by companies that are larger than they were a quarter of a century ago, work in more capital-intensive situations, work and live in large urban concentrations, and are even more diverse. Workers in call centers, hospitals, hotels, many large retail stores, and Internet retailers that are basically warehouses plus call centers work in numbers and under conditions that might well qualify them as part of today’s core as much as many factory workers. This is not just the case for workers directly involved in logistics and vulnerable supply chains. The growing number of workers employed to maintain and clean capital’s fixed assets, including not only factories and warehouses but its office buildings, airports, bus and railroad stations, hotels, hospitals, schools, universities, and so on have power not only by virtue of the embeddedness of these facilities but also as a result of the massive and constant reproduction of waste and filth such agglomerations create when profit is more important than the prevention of waste and pollution. The same is true of much of the labor of reproduction now performed in capitalist institutions, many of them having large concentrations of workers. The relative success in recent years in organizing building cleaners, hotel workers, and hospital employees gives testimony to this power. Indeed, some of the most militant strikes have been conducted and led by women outside the core in the proletarianizing professions, such as the monthlong strike by 1,500 members of the Pennsylvania Association of Staff Nurses and Allied Professionals against Temple University Hospital and the nine-day 2012 strike of the 30,000-member Chicago Teachers Union.

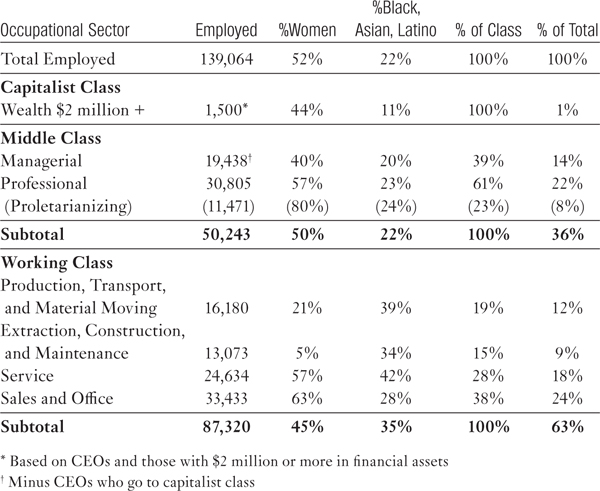

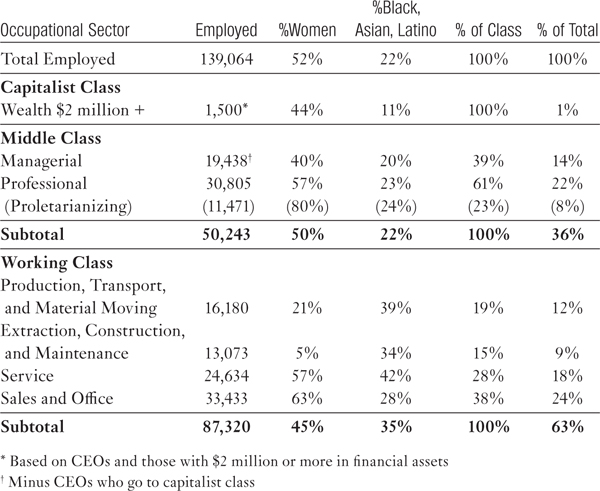

Table III summarizes the shape of US class structure today in very rough terms. Although I have not attempted to track the detailed shifting of some workers from working-class jobs to those in the middle class and vice versa conducted by Michael Zweig, the proportional results are almost the same, at about 63 percent of the workforce, and close enough for our purposes here.13 Counting up the numbers does not tell us much about class relations in itself, but it can help us conceptualize the proportions, demographics, and occupational distribution between and within the three major classes of modern capitalism. Broad occupational categories are used rather than industry figures, in part because they sort out management from labor and give us a fairly good idea of those who must sell their labor power, work under the control of capital, and work longer hours than it takes to produce their own compensation, whether or not they directly produce surplus value. In relation to the core/concentric circles model mentioned above, the twenty-nine million or so workers involved in the production and movement of material commodities represent the core, larger here because these categories cross various industry lines, while service occupations, most of which involve a mixture of material change as well as direct service, reflect the next circle, many of whose members work in large firms and workplaces and possess significant social power. The third circle is composed of the millions of office and sales workers, some of whom are concentrated in large offices, retail outlets, call centers, and so on.

Table III: Rough Guide to Class Structure in the United States, ca. 2010 (in thousands)

Source: US Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012 (Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 2011), 393–97, 467–68.

In table III, the capitalist class is defined not by income but by the ownership of capital, in this case the admittedly somewhat arbitrary net wealth of over $2 million. “Middle class” refers not to those statistically in the middle-income range or all those between the rich and the poor, but those socially located between capital and the working class in terms of the production of society’s wealth. These are mostly managerial and professional people. The working class, of course, comprises those employed directly by and paid from capital. What we see in table III is not only that the working class embraces nearly two-thirds of those employed but is far more racially diverse than the middle class and more than three times that of the capitalist class. In numerical terms, although the working class is still majority white, the vast majority of employed people of color are working class. Workers in traditional goods or extractive producing jobs compose just over a third of the employed working class as it is today. Many of the 28 percent who work in service jobs in fact produce materials goods or results, and many are now concentrated in the large workplaces that reproduce many of the conditions of factories of old and the lean methods of the neoliberal era.

Even many of those among the sales and office workers are now often concentrated in relatively large work settings such as big-box retailers, supermarkets, Internet retailers, call centers, and so on. Given the dynamics of capital’s constant push to control and standardize all forms of work, many in the middle class, who belong in proletarianizing professions such as teaching and nursing, who compose almost a quarter of the middle class, are increasingly approximating the conditions of working-class work and existence. We see this in the successful organizing and many strikes of nurses and teachers in particular. If these two groups and the leaps in consciousness they have displayed in recent years are at all typical, the numerical growth of the working class will be accompanied by increased militancy and class consciousness.

The working class, as opposed simply to the workforce, of course, is composed not only of its employed members but of nonworking spouses, dependents, relatives, the unemployed, and all those who make up the reserve army of labor. If working-class people in employment make up just under two-thirds of the workforce, those in the class amount to at least three-quarters of the population—the overwhelming majority. As teachers, nurses, and other professionals are pushed down into the working class, the majority grows even larger. If the “99 percent” popularized by the Occupy movement is not quite accurate, there being too many middle-class people tied materially and mentally to the capitalist class, the percentage of those whose fundamental interests are opposed to capital nonetheless moves in that direction.

The industrial, occupational, and ethno-racial changes in the demographics of the working class over the past three decades or more tell only half the story of the remaking of the US working class. Equally if not more important are both the new terrain on which class conflict occurs and the new sources of power this brings to many sections of the class formerly thought of as peripheral; closer to the core in their conditions and settings of work and in the leverage they have over capital’s restructured and reorganized processes of production. Millions of service, sales, and even office workers now work in larger, more capital-intensive workplaces, embedded in larger concentrations of capital, and owned by fewer capitalists. They are increasingly linked together in vulnerable technology-driven supply chains, themselves organized around enormous logistics clusters that concentrate tens and even hundreds of thousands of workers in finite geographical sites. It is to this side of class formation that we now turn.