Introduction

In the previous chapter, we explained that the millennial and post-Millennial Generations are imbued with a sense of demanding that organizations (and governments) be more socially and environmentally aware. Increasingly, we are witnessing how an organization’s performance as corporate citizens is impacting their reputation and from that consumers’ purchasing behaviour. Of course, through social media any perceived breach of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) can be broadcast globally in seconds. There’s no hiding place, and the ensuing damage to reputation (and from that earnings) can be considerable.

However, the possession of a strong sense of social and environmental responsibility is not the creation of Millennials, neither is it particularly new to how many organizations do business. Many firms were notably charitable in the nineteenth, and early decades of the 20th, centuries (although often viewed negatively, as it was seen as giving away shareholder funds without their consent), but we can see the idea of CSR emerging more formally post-World War II.

Corporate Social Responsibility

As early as 1946, Fortune Magazine polled business executives asking them about their social responsibilities. As academic Archie Carroll explained in A History of Corporate Social Responsibility: Concepts and Practices, “The results of this survey suggest what was developing in the minds of business people in the 1940s. One question asked the businessmen whether they were responsible for the consequences of their actions in a sphere wider than that covered by their profit and loss statements. Of those polled, 93.5% said yes. Second, they were asked ‘about what proportion of the businessmen you know would you rate as having a social consciousness of this sort?’ The most frequent responses were in the categories of ‘about a half’ and ‘about three quarters.’ These results seem to support the idea that the concept of trusteeship or stewardship was a growing phenomenon among business leaders.” [1]

The 1950s saw the wider acceptance of such ideas, driven somewhat by the 1953 publication of Howard Bowen’s landmark book Social Responsibilities of the Businessman [2]. This was the first comprehensive discussion of business ethics and social responsibility and created a foundation by which business executives and academics could consider the subjects as part of strategic planning and managerial decision making. But clearly, as the title suggests, as does the questions in the previous example, the idea of businesswomen had yet to take root!

Triple Bottom Line

The next major development came in 1994, when John Elkington coined the term, “Triple Bottom Line”—a concept that encourages the assessment of overall business performance based on three important areas: profit, people, and planet. Importantly, key to the model was that each of these areas would be rigorously measured.

The Triple Bottom Line idea emerged around the same time as the Balanced Scorecard, and with both aiming to more formally “balance” financials and non-financials, we witnessed early examples of the models merging and, as a result, starting to position CSR as more directly impacting strategy execution. As with many of the “non-traditional” approaches to management (such as abandoning the budget: see the Statoil example in Chap. 7: Aligning the Financial and Operational Drivers of Strategic Success) Scandinavia provided the pioneers.

Nova Nordisk Case Illustration

Headquartered in Bagsværd, Denmark, multinational pharmaceutical company Nova Nordisk introduced a Balanced Scorecard in 1995 that was based on the principles of the Triple Bottom Line. In a 2001 report written by one of the authors of this book, Peter Moeller, then Novo Nordisk’s Vice President, Organizational Development, explained that utilizing the Balanced Scorecard framework provided a vehicle for focusing on the critical few performance objectives and targets that would make a difference. “It is an excellent way to systemize the company’s tradition of focusing on much more than financial measures,” he said [3].

Within the scorecard, the learning and growth perspective included an objective on “equal opportunity.” The company decided to focus on this as a critical objective because of its obligations to social responsibility and, over the following three years, worked to ensure that equal opportunities were fully ingrained into the policies and practices of the company. Therefore, equal opportunity objectives, KPIs, and targets were captured on the corporate scorecard and mandated onto scorecards throughout the company. Note that this particular area was chosen partly as a result of the organization recognizing that, although environmental performance standards and measures were well embedded into the company, those for social responsibility were much less so.

More than 20 years later, this integrated model is still in place within the organization: indeed, The Triple Bottom Line principle is now Novo Nordisk’s business approach and was included in the Articles of Association in 2004 [4].

In the 2016 Annual Report, Lars Fruergaard Jørgensenn, Nova Nordisk’s President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) said this in his CEO letter, which neatly summarized the organizations sense of purpose and how this aligns with that of the individual and the role that Triple Bottom Line plays in this [5].

“It is not just what we do, but also how we do it that makes Novo Nordisk a special company. The ‘Novo Nordisk Way,’ describes who we are, where we want to go and the values that characterize our company.”

He added that, “Over the years, it has become clear to me that the Novo Nordisk Way is the reason why many of our employees are working here and not somewhere else. It is about always having patients’ interests in mind, about always doing what is best in the long run and about doing business in accordance with the Triple Bottom Line business principle, which means that we always consider the financial, environmental and social impacts of our decisions.”

Sustainability Strategy Map

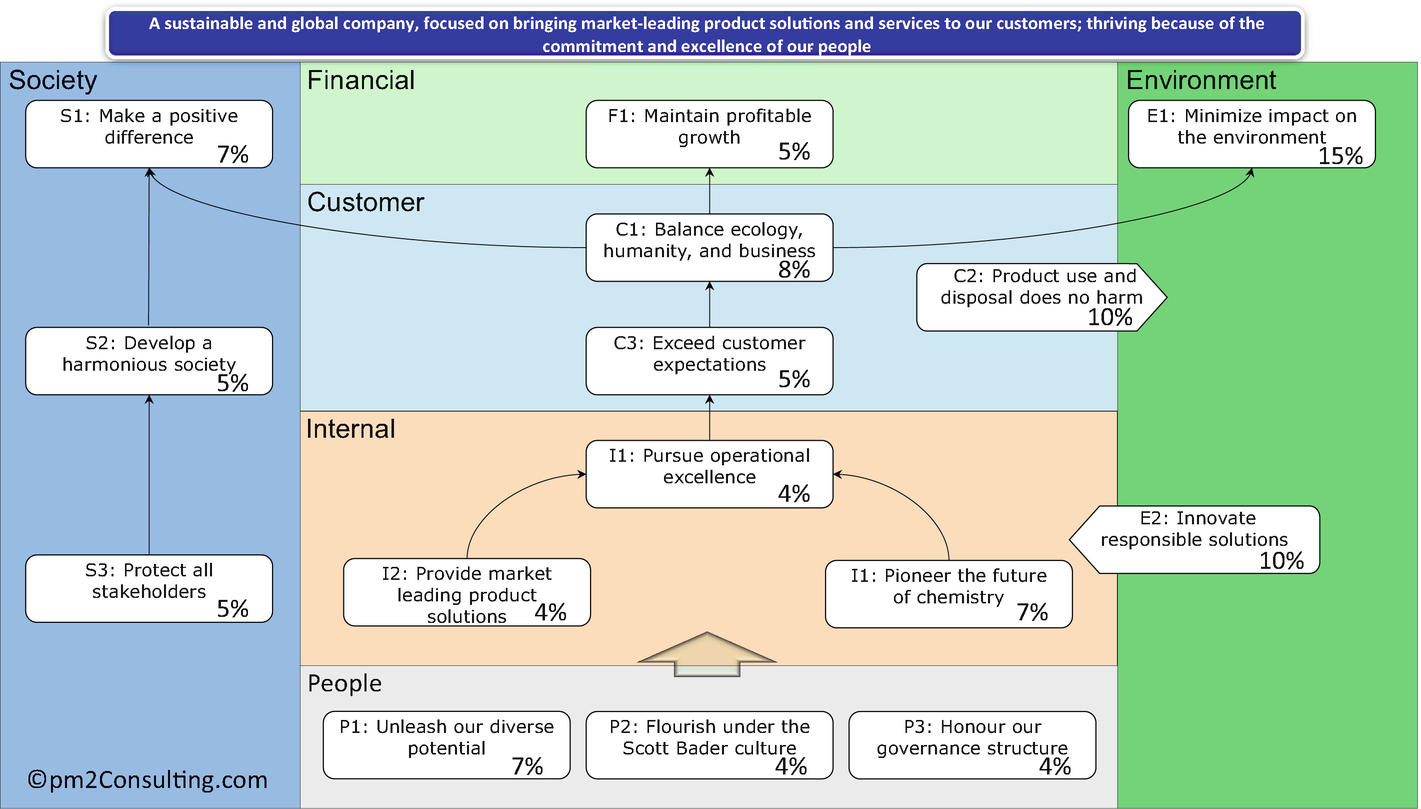

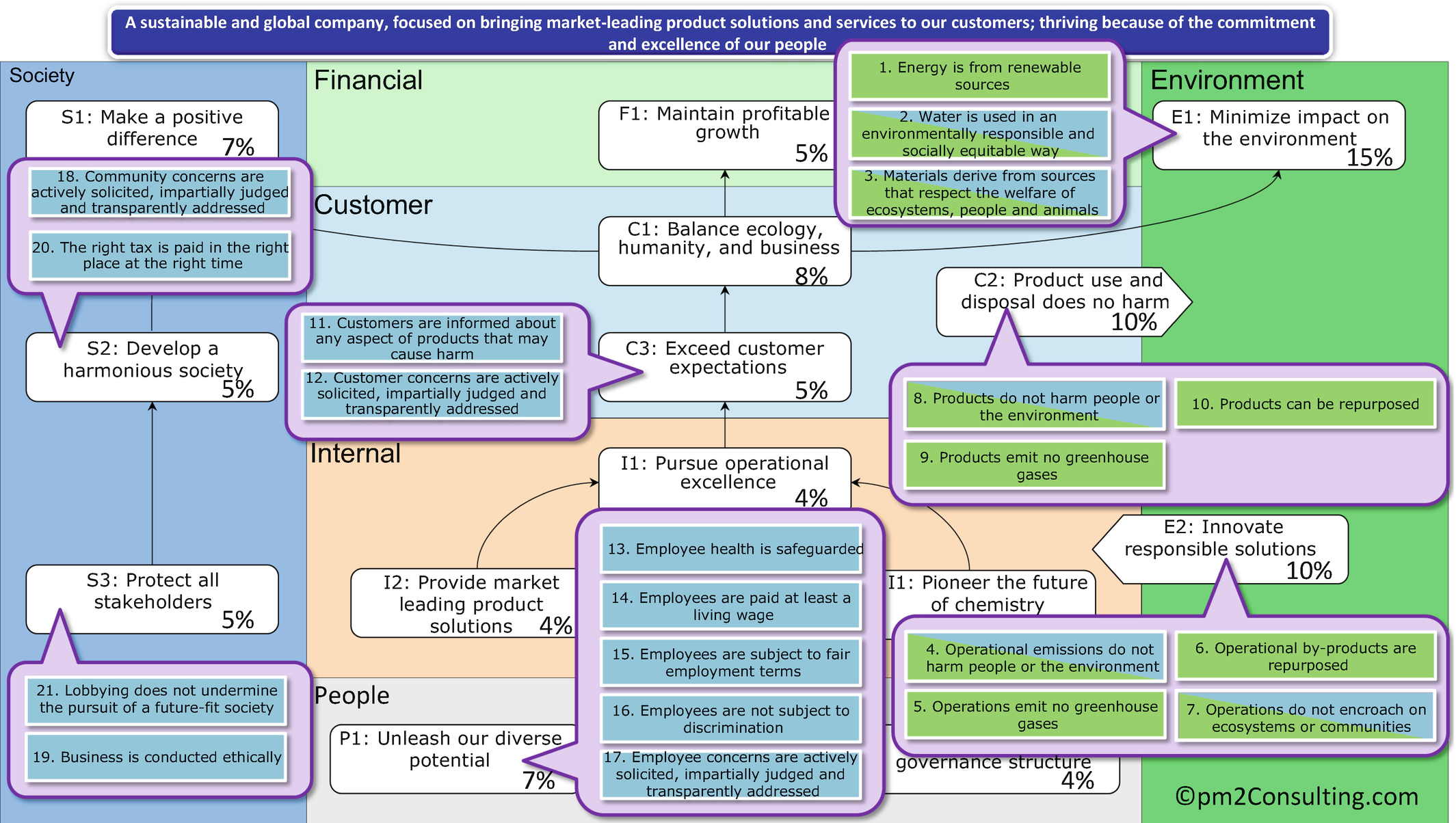

Over the past couple of decades, there have been numerous other examples of organizations utilizing the Balanced Scorecard system to drive CSR and developing frameworks to do this. One useful recent spin is the Sustainability Strategy Map, developed by Canada-headquartered consulting firm Pm2Consulting (Performance Measurement & Management). In a May 2017 LinkedIn article, founder and CEO Brett Knowles, stated that, “We now need to integrate this new best-practice around measuring environmental and societal business impacts with the third ‘bottom-line’… business success.”

Best practices on measuring business success comes, he writes, from the Balanced Scorecard body of knowledge. In the approach pioneered by Pm2Consulting, this is aligned to the 21 Sustainability Business Goals with specific measures and formulas that are found in the Future-Fit Business Benchmark. The goals, as examples Energy is from renewable sources, Products do not harm people or the environment, Employees are paid at least a living wage and Business is conducted ethically.

A Sustainability Strategy Map. (Source: pm2Consulting)

A Sustainability Strategy Map aligned to the 21 Sustainability Business Goals. (Source: pm2Consulting)

Shared Value

Professor Robert Kaplan has been championing the use of the Balanced Scorecard to improve social and environmental performance for some time, but has an issue with the term CSR. He explains, “The problem with CSR is built into its name. ‘Responsibility’ suggests that CSR is a tax on companies, something they should do altruistically or to keep their stakeholder groups at bay. Viewed this way, CSR becomes a cost of doing business” [7].

Kaplan prefers a “shared value” approach which, he says, “encourages companies to think creatively to find new ways of doing business that not only generate financial returns for them but also enable them to be environmentally sustainable and to contribute to communities in which they source, produce, distribute, market, and sell.”

Shared Value Explained

As a brief explanation, Professors Michael Porter and Mark Kramer introduced the shared value concept in the 2011 Harvard Business Review article, Creating Shared Value [8]. Launched in the wake of the financial crisis, shared value was a way to “reinvent capitalism.” As the authors wrote: “In recent years, business has been criticized as a major cause of social, environmental, and economic problems. Companies are widely thought to be prospering at the expense of their communities. Trust in business has fallen to new lows, leading government officials to set policies that undermine competitiveness and sap economic growth. Business is caught in a vicious circle.”

They continued that a big part of the problem lies with companies themselves, “which remain trapped in an outdated, narrow approach to value creation,” Porter and Kramer argue. “Focused on optimizing short-term financial performance, they overlook the greatest unmet needs in the market as well as broader influences on their long-term success. Why else would companies ignore the well-being of their customers, the depletion of natural resources vital to their businesses, the viability of suppliers, and the economic distress of the communities in which they produce and sell?”

In essence, shared value “reinvents capitalism,” by tying business value (profit, etc.) to value for communities and without environmental degradation. According to Porter and Kramer, “firms can do this in three distinct ways: by reconceiving products and markets, redefining productivity in the value chain, and building supportive industry clusters at the company’s location.”

As detailed in Panel 1, Professor Kaplan would like to see many more Strategy Maps and scorecards reflecting environmental and community objectives, but it’s possible to take the shared value philosophy even further and build in the idea of collaboration and networks. Moreover, he explains how this all ties back to a sense of purpose.

Positive Impact

With a corporate mission to deliver a “Positive Impact”—that is social, economic, and environmental value—The Palladium Group (a firm originally led by Doctors Kaplan and Norton) is building on the shared value ideas by playing the role of a catalyst in “Positive Impact Partnerships.” These partnerships work to share governance mechanisms to ensure transparency, engagement, and alignment, while holding actors to account. Through the Balanced Scorecard concept, it encourages multiple companies to co-create a Strategy Map and scorecard related to a specific partnership, with the goal to promote collaboration, alignment, and commitment among all stakeholders.

Palladium is applying this concept in its work with Syngenta, a large agribusiness, where it is supporting the development of system Strategy Maps with cascading scorecards for each of the actors involved in their good growth plan interventions in Indonesia and Nicaragua. According to Juan Gonzalez-Valero, Head of Public Policy and Sustainability at Syngenta, “If you take agriculture…it’s [about]… understanding what is actually necessary to capture value before the farm, on the farm, and after the farm. If we agree on the Strategy Map overall, we can agree on certain metrics that will help all the players get involved, and I think that holds true for all sectors” [9].

Networked Organizations

Such networked organizations represent an emerging and powerful application of the Balanced Scorecard S ystem. These networks bring together distinct organizations and groups of people to deliver collective outcomes while also achieving the goals of each individual network member. Such networked—and oftentimes virtual—collaborative structures are becoming more commonplace as organizations struggle with the complex challenges of the twenty-first century.

Networked organizations vary widely depending upon their collective goals. They might consist of public sector organizations, private sector organizations, or a combination of both. They might be short term in nature (e.g. delivering a specific innovation project) or longer term (dealing with deeply ingrained socioeconomic challenges). The structure of these collaborations can exaggerate the same issues that organizations face individually. Networked organizations struggle to assign accountabilities, maintain transparency, and measure progress. Further, the looseness of the affiliation between network members creates a culture in which it is easy to assign blame elsewhere.

The Balanced Scorecard system addresses these obstacles by aligning the disparate network members around a common strategy to which they all contribute and by creating a platform through which each partner can understand their progress toward a common goal. The following case example showcases a successful implementation of the Balanced Scorecard system across a large network of partners seeking to drive positive outcomes in their community.

Case Illustration: Thriving Weld

Healthy Eating;

Active Living;

Healthy Mind and Spirit;

Access to Care;

Livelihood;

Education; and

Health Equity.

At the outset, the scorecard system appealed to the Weld County Department of Public Health and Environment because it recognized that no single organization could successfully address all the priority health issues and social determinants of health in their community. Previously, each organization developed its strategy, measurements, reporting, and communication structures independent of one another. As a result, Weld County’s many efforts to improve the health and wellbeing of their community faced problems of fragmentation, wasteful redundancy, and inefficiency.

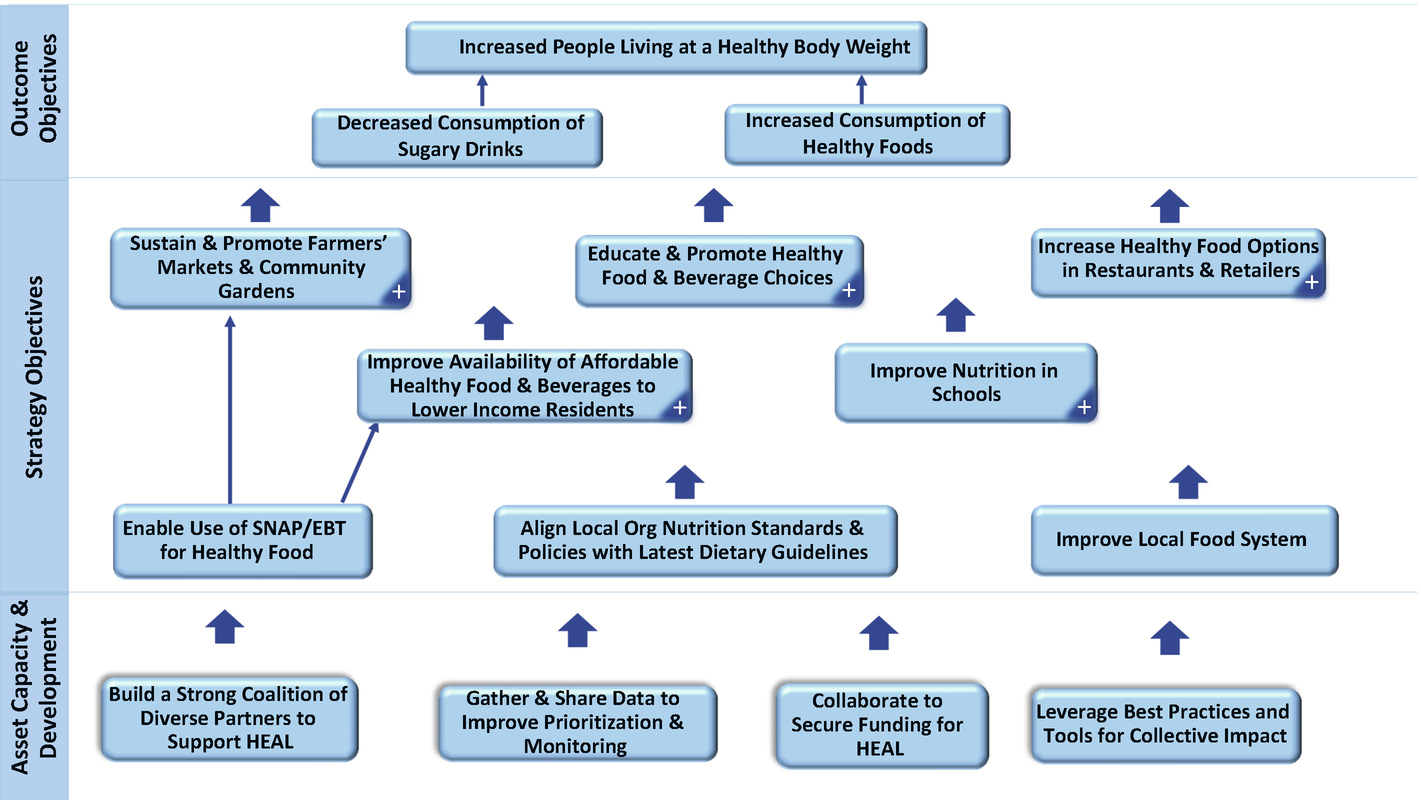

Outcomes are what the multi-agency partnership wishes to achieve collectively. For example, the ultimate outcome in the Healthy Eating focus area is “Increased People Living at a Healthy Body Weight.”

Strategies (such as “Increase Healthy Food Options in Restaurants and Retailers”) deliver the outcomes, essentially combining the conventional customer and process perspectives.

Assets and capacity development capture the prerequisites for achieving the strategies, much as the learning and growth perspective supports the Process perspective in conventional scorecards. Here, we find objectives such as “Gather and Share Data to Improve Prioritization and Monitoring.”

Thriving Weld County Strategy Map. (Source: Insightformation)

As with a conventional strategy map or scorecard, cause and effect build from the bottom to the top.

Zoomable Strategy Maps

High-level focus area Strategy Maps are composed of objectives that are too big for any one organization to be solely accountable. Thriving Weld addressed this issue using technology-enabled Strategy Maps that can zoom in or out to show various levels of detail, like a digital map on a GPS. Stakeholders can view a high-level Strategy Map to understand the big picture, then zoom in and view the details of a given objective, narrowing in on those that are most relevant to them. The zoom feature enables all partners to work towards the focus area outcomes through their own spheres of work, while benefiting from the insights and data provided by the group as a whole.

Robust Shared Measurement System

The focus area Strategy Maps provide the structure for a shared measurement system. Each outcome’s objective has one or two measures to monitor the community’s progress.

Because changes at a community level take years to achieve, outcome measures move very slowly. Instead, progress in the short term is evident in the Strategies perspective, which supports the outcome perspective. The Balanced Scorecard methodology emphasizes the importance of leading indicators, which in this case is accomplished with driver measures and associated targets that monitor the progress of objectives in the strategies perspective.

Before launching Thriving Weld, individual organizations would select their own measures for their programs, frustrating collaborative efforts even when organizations were working toward common goals. Today, the process is inverted: organizations make program and funding decisions according to their expected impact on the driver measures, which are shared across the network—providing a powerful incentive for teamwork.

As with a conventional scorecard system, thoughtfully selected initiatives propel progress on objectives—but Weld County uses the term action instead. Community-oriented organizations are accustomed to creating and implementing action plans, so the familiar term “action” resonates better than the more nebulous “initiative.” Language is important for buy-in.

Transparency and visibility, also central to buy-in, are seen as the keys to success. The Strategy Maps and scorecards for dozens of community partners are available for the public to view on Thriving Weld’s website [10]. These pages automatically update with the latest data from the centralized measure collection system.

The Million Dollar Question: Is This Approach Creating the Desired Impact?

When dealing with deeply entrenched community issues like obesity and chronic disease, the time lag between embracing a new approach and seeing the outcome in the community can be considerable. It takes time to change the systems, the environment, and people’s behaviours. It takes time for those changes to impact health outcomes. It takes time to collect and validate data.

Although it is early still to see the kinds of results Thriving Weld eventually intends to produce, there are, however, many encouraging signs of progress that show that this approach is creating alignment, action, and positive movement to implement the strategy.

Improved Communication

We’ve had a lot of energy and activity around becoming a healthy county for quite a few years. But in the past, it was like all the organizations were…people talking in a crowded restaurant. All the different conversations ended up creating a lot of noise. Now, with a shared strategy that is clearly communicated using the strategy maps, it is like being in a theatre with surround sound [11].

Improved Alignment of Funders and Other Stakeholders

Grant makers have a huge impact on how non-profit organizations work in a community. Because of their participation in Thriving Weld’s Balanced Scorecard program, the United Way of Weld County decided to align their funding to the objectives on the Strategy Maps and have grantees report their performance using the shared measurement system. In turn, this decision led to greater interest among community organizations in how Strategy Maps can support improvements to critical goals.

Improved Engagement and New Actions

Having a clear set of shared priority objectives has inspired many community organizations to launch creative actions to address their community’s needs. This list of new efforts is long and varied. For example, in 2015, community partners launched a new initiative to improve active recreation for minority youth by offering “Family Fun Passes” to a nearby funplex. Nearly 1400 families registered and over 3500 passes were used. In 2014, 35 organizations incorporated plans or messaging about active living and reducing the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages into their communication and modelling to youth. While many of these initiatives are small, their collective impact reveals the strength of the community’s engagement in achieving big goals together.

Parting Words

The Thriving Weld experience and other similar ventures (see, as examples, the Insightformation or Palladium websites, [12, 13]), show how collaborative scorecards can address complex social challenges, from improving the quality of life in economically disadvantaged communities to addressing crisis areas such as drug abuse. The potential is far-reaching—by adapting a system developed for the private sector to address the ever-evolving needs of the public sector, organizations spur innovative solutions to truly pressing problems. Such examples provide compelling evidence of delivering positive collective impact through a collaborative, networked structure.

Professor Kaplan provides this powerful statement, which can serve as a call to arms! “In his Gettysburg Address, President Lincoln spoke about democracy as ‘government of the people, by the people and for the people.’ Shared Value strategies today are about delivering value for citizens. A collaborative and co-created Shared Value Strategy can channel Abraham Lincoln by having the shared value created ‘of the people, by the people, and for the people.’”

Panel 1: Co-Created Balanced Scorecard

In a June 2015 edition of Strategically Speaking (which was edited by one of the authors of this book), selected experts were posed the question, “How Can Companies Do More Good for Society and Turn a Profit?” The following is an extract from the reply provided by Professor Robert Kaplan, [7].

A Changing Social Context

With the growth of democracy around the globe during the past 50 years, more people want their voices to be heard. They voice their concerns as to the adverse social and environmental impacts from companies working within their local communities.... people are rebelling against the massive pollution being created by power generation and industrial operations. After not paying attention to these externalities for 200 years, companies should be able to find many opportunities (“low-hanging fruit”) to respond to these concerns without having an adverse effect on their bottom line.

Beyond the spread of democracy, the Internet and social media have given people much more knowledge about standards of living and working practices in various parts of the world. This information causes them to question the practices of companies in their communities and nations.

As people in developed nations move up the Maslovian scale of needs, they no longer worry about basic needs such as food and shelter. Many seek more fulfilling and meaningful lives. They want to work for organizations that can help deliver that higher sense of purpose work that they feel good about and whose mission they believe in and aligns to their own.

Shared value helps companies meet employees’ expectations for work that not only provides employment and income, but also delivers value to all a company’s stakeholders—including, of course, its shareholders. A company creates meaningful employment when it delivers on its mission, defined by how it creates value for customers. The mission statement of the pharmaceutical company Merck, for example, says that medicine is for people, not profits. But, Merck also notes that the better they have gotten at delivering medicine for people, the more profits have followed. Profit is a score of how well a company delivers value to its customers.

The Balanced Scorecard

Dave Norton and I developed the Balanced Scorecard because we recognized that quarterly and annual profit are not a complete metric of whether a company created or destroyed shareholder value in a given period. The way to maximize long-term value is to continue to be innovative in delivering value to customers. Innovation is also central to a good shared value strategy. Companies must search for new and better ways to create value, sustainably, for shareholders, customers, suppliers, employees, and communities throughout their value chain.

Over the past 20 years, we have interacted with many companies that want to quantify their performance in making positive social and environmental impacts. Several have created environmental and community performance strategic objectives on their maps and several have introduced a fifth perspective for environmental and social performance.

This made such performance a core part of the strategy for which the entire executive team would be accountable. In contrast, the CSR approach was often delegated to a separate function or the corporate foundation.

Co-Creation

I would like to see many more strategy maps and scorecards reflecting environmental and community objectives. But, we can take the shared value philosophy even further.

The best shared value strategies should be co-created by companies, NGOs, community representatives, and other key stakeholders. The co-creation creates a consensus as to the value that must be delivered for each group and who will be responsible and accountable for the various objectives.

The co-creation process also creates trust and understanding among the groups. The non-corporate stakeholders will recognize that a corporate commitment to the shared value strategy can only be sustained if the company earns adequate financial returns from the strategy. Even after the shared value strategy map and scorecard have been co-created, the collaboration process continues by inviting the stakeholders to participate in strategy review meetings to discuss performance, accomplishments, shortfalls, and new improvement opportunities. A good measurement system will be critical, and all parties will need to build robust metrics for environmental, social, and community impacts.

Self-Assessment Checklist

The following self-assessment assists the reader in identifying strengths and opportunities for improvement against the key performance dimension that we consider critical for succeeding with strategy management in the digital age.

Self-assessment checklist

Please tick the number that is the closest to the statement with which you agree | ||||||||

7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

My organization has a very strong sense of social and environmental responsibility | My organization has a very weak sense of social and environmental responsibility | |||||||

My organization has very well defined social and environmental strategic objectives | My organization has not defined any social and environmental strategic objectives | |||||||

My organization has a very effective process for managing external networks | My organization has a very ineffective process for managing external networks | |||||||

My organization has a very effective process for managing internal networks | My organization has a very ineffective process for managing internal networks | |||||||