Introduction

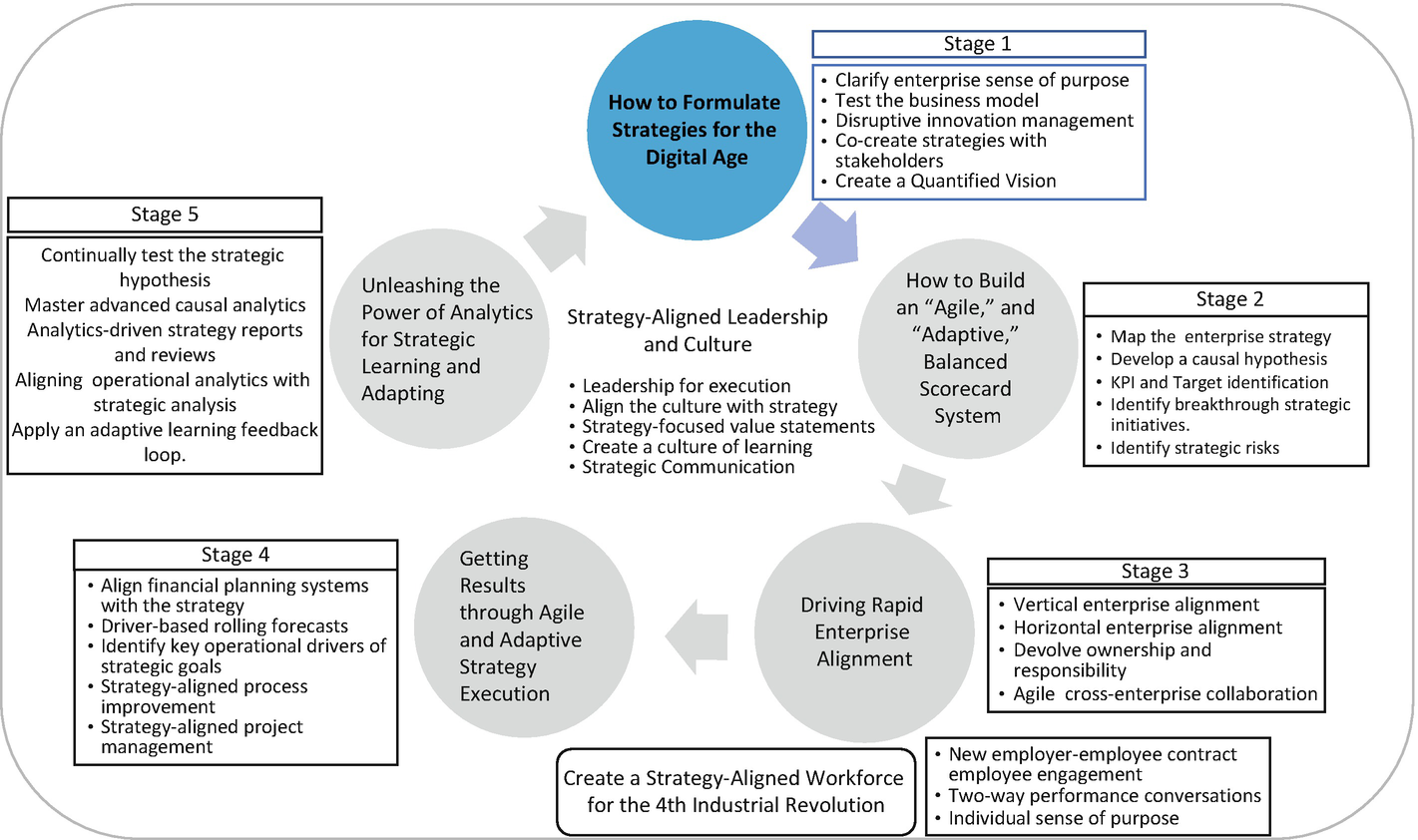

Stage 1: How to formulate strategies for the digital age

Crafting a Vision Statement

Where strategy starts to become more agile is in the setting of shorter-term and medium-term goals and their delivery mechanisms. Here, being able to respond quickly to opportunities and threats becomes a competitive differentiator. The first step is to craft the vision of the organization. As with a mission statement, organizations often fail to capture the power of the vision as a strategic steer.

Not Visions: Advertising Slogans

A trawl through the recent vision statements of Fortune Global 100 companies uncovers some real gems: “To be the best consumer products and services company in the world,” (Procter and Gamble); “To become a leading global energy company,” (Lukoil); “Enel is the Leading producer and distributor of gas” (Enel); “To be the most competitive and productive service organization in the world,” (Sociate General); and a real beauty, “No 1 LG” (LG).

Note that we are not picking on these companies specifically. Most of the vision statements that we reviewed are similarly vague and, to be blunt, of limited value. Such statements tell the reader nothing about what the organization wants to achieve over the timeline of the strategy, what success will look like, or how that will be achieved. What exactly does “a leading” company mean? Or to be “the best,” and the mind simply boggles at trying to make sense of No 1 (in what exactly?). They are not visions—they are advertising slogans.

Moreover, some of the Fortune vision statements confused setting a goal and direction with values. For instance, “The continued success of Costco depends on how well each of Costco’s employees adheres to the highest standards mandated by the company’s code of ethics?” Applaudable, but hardly a vision.

Executable Visions

When crafting a vision statement, a critical question is “how will an employee (tasked with implementing the vision) understand what they are supposed to do differently to deliver success?” In our training workshops, we typically ask participants to state their organization’s vision: most get on their smartphone to look it up. Hardly a sign that they find the words inspirational. Of course, it also means they are not being aligned to the vision.

The shaping of the vision statement is the most important step in the strategy planning process (and planning is different from the strategy setting steps described in the previous chapter). The vision is the anchor for all subsequent thinking—up to the identification of the strategic objectives, measures, targets, and initiatives that appear within a Balanced Scorecard system and throughout execution. The vision should precisely describe what the organization wishes to achieve through its strategy: the end goal.

A Quantified Vision

A well-crafted vision statement should be inspirational, aspirational, and, crucially, measurable (to capture whether, or not, the strategy has been successful). A “quantified” vision helps here.

Case Illustrations

Early scorecard adopter CIGNA Property and Casualty shaped a quantified vision to drive a major transformation exercise, which included a significant shift in market positioning and to turnaround horrendous financial losses. The vision simply and succinctly read, “To be a top-quartile [in profitability] specialist within five years.” Thet were previously a generalist, so played in most insurance spaces.

The vision triggered, among other interventions, significant organizational restructuring. The firm, which had lost over a $1 billion over a three-year period, returned to profitability just two years post defining the new vision and implementing a scorecard [1].

As a further example, from the public sector (a University), “By 2015, our distinctive ability to integrate world class research, scholarship and education will have secured us a place among the top 50 universities in the world.” Again, success indicator, niche, and timeframe are specified.

Mid-Term Visions

In short, a quantified statement moves the vision from a simple outcome statement (“to become the preferred supplier”) to a more comprehensive picture of the enabling factors with which to achieve the vision. It provides clarity of focus and priorities.

A quantified vision is set for the lifetime of the strategy, so perhaps five years. Although appropriate, given the speed of change these days and the requirement for more agile and adaptive strategic manoeuvres it is often sensible to quantify a supporting vision over the mid-term: say, two years. This is consistent with the practice of mid-term planning, in which the mid-term plan provides more implementation details than the longer-term strategic plan and acts as connector to the annual plan. Typically, strategic initiatives are set over the mid-term, so this aligns well the Balanced Scorecard approach. It is over the shorter term that strategy comes alive, without losing sight of the guiding star that are the longer-term goals.

Moreover, five years is typically too extended a timeframe for employees to take particularly seriously: increasingly, a large percentage would have departed the organization by then and/or will believe that something will happen to completely change the organization before the years have elapsed (which is not uncommon these days).

Mid-term goals are more tangible and provide a greater sense of urgency. Furthermore, if the organization has a major transformational strategy, perhaps with very stretching financial goals that require significant organizational restructuring, geographical shifts in market focus, and new capability building, then the five-year vision runs the danger of simply being overwhelming.

Advice Snippet

- 1.

A quantified success indicator (such as Cigna’s top quartile in profitability)

- 2.

A definition of one’s niche (switching from generalist to specialist)

- 3.

A designated timeframe (within five years).

Identifying the Value Gap

The quantified vision provides the base for identifying the “value gap,” which is the difference between the organization’s current performance and the quantified targets. Again, this can be done both over the lifetime of the strategy as well as over the mid-term.

The value gap becomes a powerful steer for planning and subsequent prioritization and resource allocation. For instance, say an organization wishes to “double EBITDA within five years,” this might represent a $2 billion difference. The organization then needs to consider how to close the gap: via productivity or revenue growth interventions. It can then put a figure to each financial measure. As an illustration, for productivity improve cost structure by $750 million and improve asset utilization by $250 million, while for revenue growth expand revenue opportunities by and increase customer value by $500 million each. With the financial targets in place, attention switches to non-financial drivers and the interventions required to deliver these targets (Customer, process, learning and growth).

As a note of warning, from our experience, the early conversations around closing the value gap often centre on productivity goals rather than revenue, as the former requires considerably less creative thinking. Care must be taken to strike a sensible balance. Downsizing, and so on, are oftentimes too casually implemented.

Crucially, the value gap serves as the steer for setting KPI targets and defining the “performance gap,”—the difference between current KPI performance and the target, for both financial and non-financial metrics. Closing performance gaps ultimately closes the value gap and this, as we explain in Chap. 8, is primarily about developing “strategy-aligned” project management capabilities and implementing the identified interventions.

The quantified vision is also a key input into the Strategic Change Agenda, which we describe later in this chapter. However, there are important steps before this.

Environmental Scanning

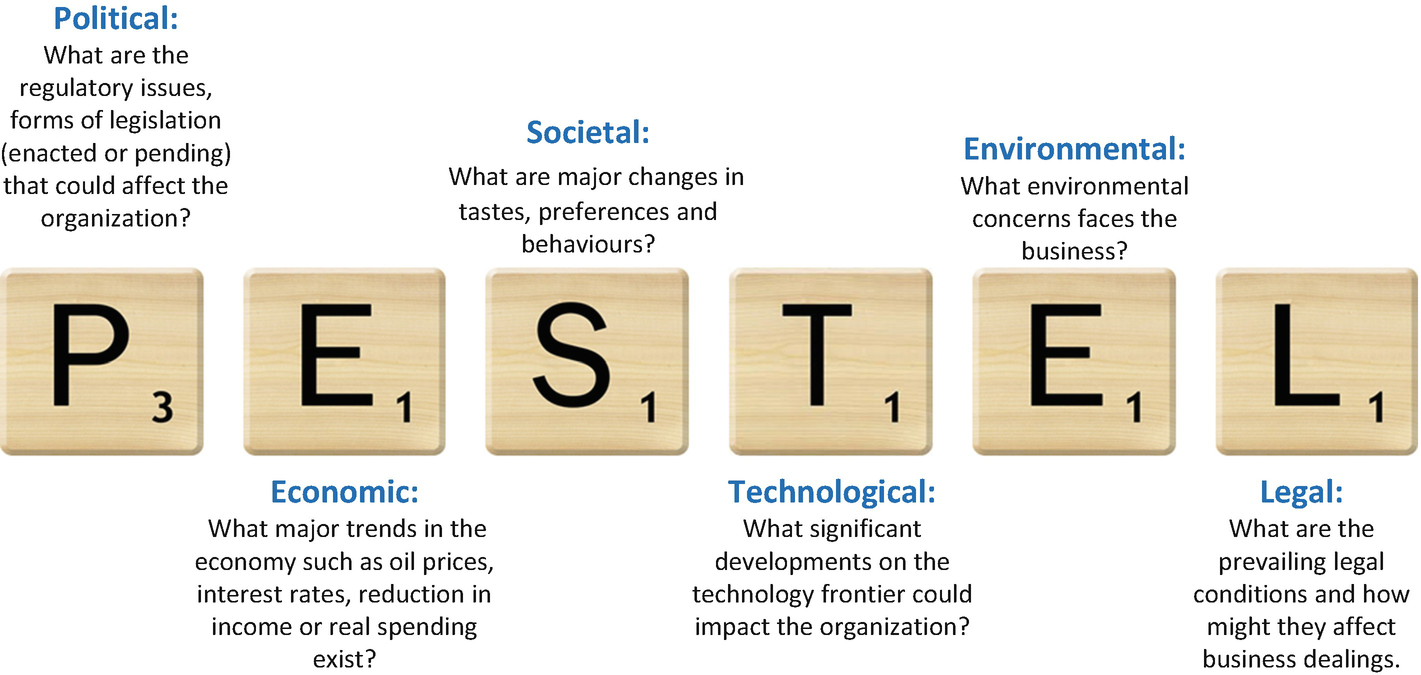

A PESTEL analysis

Porter’s Five Forces framework

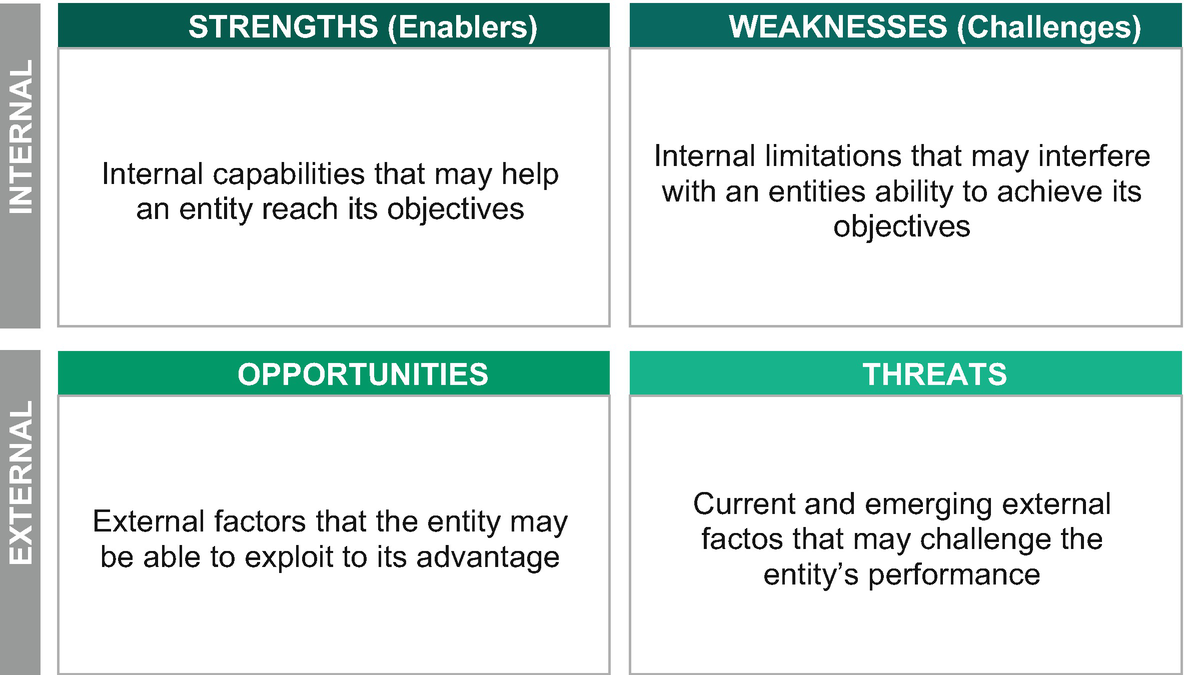

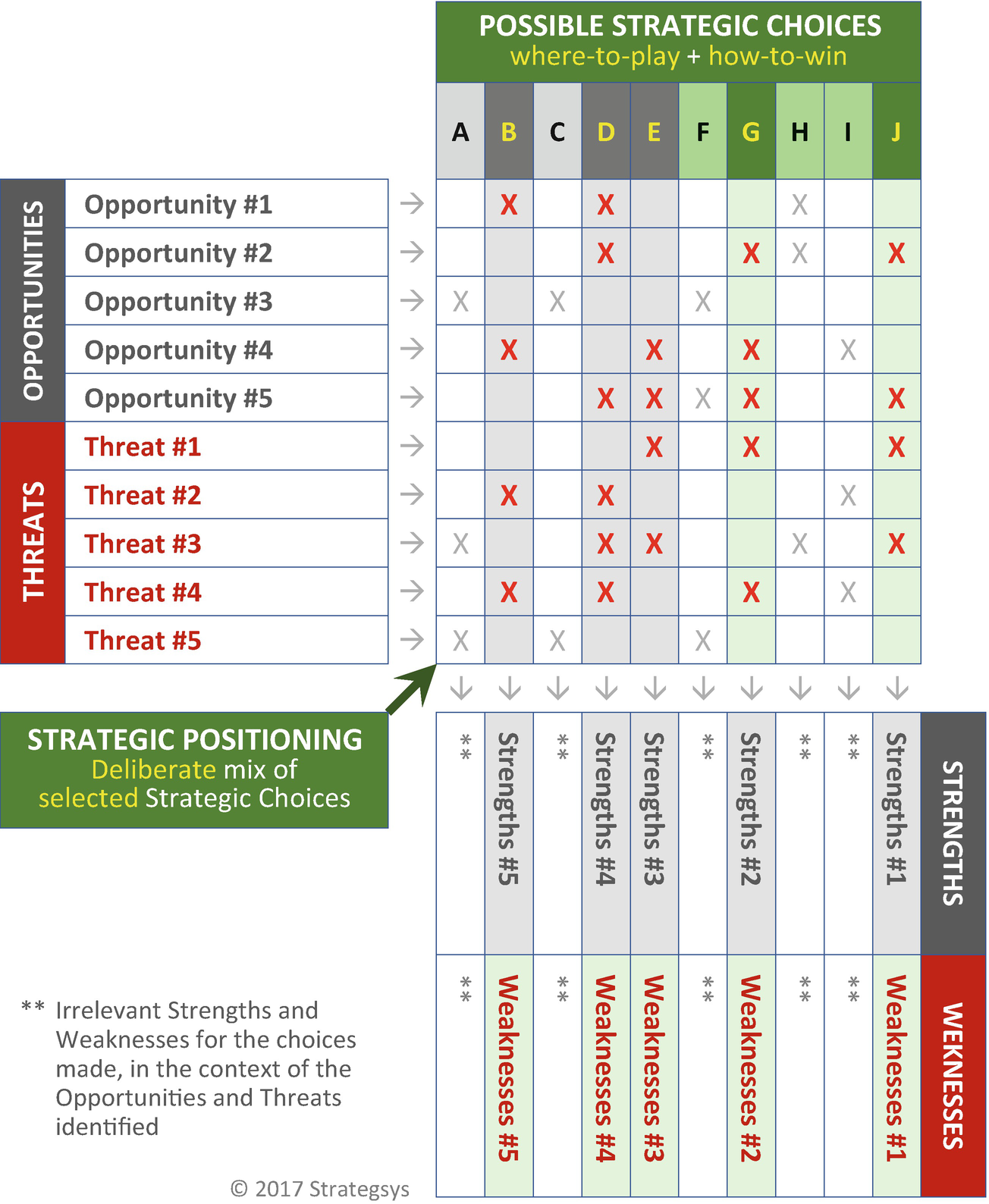

A SWOT analysis template

Strategsys SWOT analysis. (Source: Strategsys)

Many newer tools essentially do the same thing in understanding the linkage between marketplace dynamics and internal delivery models and capabilities. We describe some of the newer tools below, but this certainly not an exhaustive list—rather a flavour of what’s available.

However, whichever tools are used, we must move away from viewing them as once-a-year exercises. Scanning the external environment must be a continuous process.

Pattern-Based Strategy

The research and consulting firm Gartner has identified four disciplines to successfully adopting what they term a pattern-based strategy: pattern seeking, optempo (operational tempo) advantages, performance-driven culture, and transparency.

Pattern Seeking

Pattern seeking comprises focusing on the competencies, activities, technologies, and resources that expose signals, which may lead to a pattern that will have a positive or negative impact on strategy or operations—focusing on those areas of vulnerability or risk and innovation/opportunity for the business.

Seeking patterns can mean looking inside or outside the organization and involves exploiting the new power of the collective—that is, exploiting collective knowledge with creative activities, and exploiting collective activities as an unexplored source of patterns.

“The collective is made up of individuals, groups, communities, crowds, markets and firms that shape the direction of society and business,” said Tom Austin, Vice President and a Gartner Fellow. “The collective is not new, but technology has made it more powerful – and enabled change to happen more rapidly. The explosion of social software, for example, has enabled groups and individuals to rapidly form and rally to a cause, often resulting in significant societal changes” [2].

Optempo Advantage

Gartner terms optempo advantage as representing the set of coherent guidelines and actions necessary for maximizing the allocation and utilization of enterprise resources as new patterns emerge.

In a pattern-based strategy, an organization excels by adjusting the relative speed of its operations better than its competitors do. However, enterprises must first understand the levers they can control to drive change. These levers are people, processes, and information. Business leaders can think of an optempo advantage as a formal management philosophy for improving their organization’s competitive rhythm, so that it can match pace with purpose consistently and dynamically.

Performance-Driven Culture

A performance-driven culture enables an organization to monitor leading indicators of change. “Most organizations measure performance; they don’t manage it. The traditional focus has been on measuring high-level, financially oriented outcomes after the event. This creates a reactive sense-and-respond mind-set,” Sribar said. “Today’s environment demands looking at leading performance and risk indicators to provide a forward-looking focus that then must permeate all levels of an organization—rather than just providing top-level measures. Changes in business strategy and operations will be reflected in changes in performance metrics, which will then drive change in behaviours and operational tempo” [3].

This component in captured within a Balanced Scorecard System, as we explain in subsequent chapters.

Transparency

In the context of a pattern-based strategy, transparency means both the demonstration of corporate health and the strategic use of transparency for differentiation.

If organizations can proactively evolve transparency from a once-a-quarter financial-results event to using it to set the right expectations of seeking new patterns and responding with consistent results, this proactive use might enable them to enter new markets, gain access to funds that competitors can’t access, and demonstrate differentiation to customers and suppliers.

SCOPE Situational Analysis

Many commentators agree that SWOT (a tool originally developed in the 1960s) is somewhat out of date, although some state is still of some value. A more modern equivalent is SCOPE Situational Analysis.

S – SITUATION: Rear-view—pertaining to conditions that have a relevant and material impact on planning decisions with regards to internal or external environmental factors.

C – CORE COMPETENCIES: Unique abilities or assets of the business that provide the basis for the provision and realization of value to customers and are critical to the creation of competitive advantage.

O – OBSTACLES: Potential issues or threats that could jeopardize the realization of the core competencies and thereby impinge on prospects.

P – PROSPECTS: Opportunities that exist internally or externally to the business that can enhance sales and/or profits, created through leveraging its core competencies and overcoming obstacles.

E – EXPECTATIONS: Future-view—predictions of future internal and external conditions that are likely to materially influence, positively or negatively, the delivery of plans to meet the identified prospects.

The Danger of Being Frozen in Time

The issue with the more static scanning models is that they are descriptive (a snapshot in time) and a once-a-year exercise, and once done, not thought about again until the next strategy review process. Markets, customers, and competitors do not freeze when the external environmental scan is complete, waiting to unfreeze just before the next scan.

Organizations must keep a constant eye on the external world and institutionalize this during execution, ensuring the capabilities are in place to respond to (and, even better, predict) marketplace shifts that might derail the strategic plan by altering the underlying assumptions and so weakening the strategic choices made for implementation. As Simbarashe Tembo, Head, the Strategy Advisory, East Africa, for the consultancy Ernst & Young comments, “the problem is once the analysis has been carried out, most strategists fail to connect the dots from this point onwards. Strategic choices, objectives, initiatives etc., become disconnected from the earlier work, such as the SWOT.”

As we also explain in later chapters (most notably Chap. 9), retaining an external focus does not mean responding to every identified market movement. This will simply become a form of agile strategy firefighting.

There is still a need for a governance structure that allows for a formal review and reflection (but not just once a year). With a quantified vision set and value gap identified, a critical step here is capturing the insights of the leadership team through formal interviews (which provide critical information for the Strategic Change Agenda).

Senior Management Interviews

From our experience and observations, it is common for organizations to create a Strategy Map from scratch in a single senior management workshop and immediately post a SWOT analysis. Although seemingly valuable as it is time-efficient, this approach often leads to inappropriate outcomes. As an example, the map is shaped based on the views of the most dominant and outspoken members of the group. Conversely, the map captures the individual views of the whole team and so represents everything the organization does, not what matters strategically.

Although senior management workshops are critical (to debate and agree on the objectives, etc.), we recommend a preceding step of one-to-one interviews with the senior team, which are conducted post the environmental scanning. Based on the outputs of the previous strategy development work, these facilitated interviews are intended to tease out what each individual believes to be the key strategic outcomes and enablers, and what they personally think the organization does well and not so well.

Case Illustration: Norway-Based Power Company

A Norwegian-based power company realized the benefits of structured interviews (that were conducted by an external facilitator) when building a scorecard system in the mid-2000s. In creating the top-level Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard, the in-house team adhered to the classic scorecard creation process.

The process began with the vision of where the organization wanted to be in the future and an analysis of the strategic plan. Based on structured interviews with senior managers, a draft Strategy Map was then created, comprising objectives for the four perspectives of financial, customer, internal process, and learning and growth. The senior team then debated and refined the draft map. A final map was then created with consensus.

In an interview with one of the authors, the then-CEO described a clear benefit of the structured mapping process. “For the new strategic plan, we created a Strategy Map. However, the senior team’s discipline in discussing and agreeing the drivers of strategic success during the scorecard process meant we ended up with a Strategy Map that was very different from the one inserted in the strategic plan.”

The agreed map then became the basis for a subsequent round of interviews and discussions to create the top-level Balanced Scorecard of KPIs, targets, and strategic initiatives.

Using an External Facilitator

It is possible that this facilitator is an in-house employee, but it is usually advisable (at least in creating the first map and scorecard) that an external facilitator is used. The reasons for recommending external support at the beginning of a scorecard program are myriad.

Firstly, a Balanced Scorecard system appears remarkably simple to construct. After all, it’s basically a collection of strategic objectives with supporting KPIs, targets, and initiatives. (Does not appear that difficult to put together!). As a result, relatively junior staff with little knowledge of or experience in scorecard design and management are oftentimes tasked with its formation. This is a recipe for disaster and is why many scorecard efforts deliver little real value, and either wither and die or are reduced to KPI collection and reporting mechanisms that are effectively divorced from strategy.

An external facilitator should bring deep knowledge and extensive experience (but be careful here as this is not always the case—unfortunately, they too can be seduced by the “how hard can it be” belief).

The facilitator should know how to identify objectives and KPIs, how cause and effect works, as well as understanding how to overcome the significant challenges of rollout. In short, the facilitator should know what works, what doesn’t, and the pitfalls to avoid: something that takes a long time to develop.

Furthermore, an external facilitator should bring independence and neutrality, melding together individual views without getting involved in politics or pushing their own agenda. This is a point that should not be underestimated.

It is rare for internal people to be able to remain completely outside of the politics of the organization. Either they do not have enough perceived authority to challenge the views of the senior team or, if senior, have their own strong interests or agendas. For example, a finance director might have the authority to lead a scorecard effort, but might push their own agenda and make the scorecard too finance-oriented (this is also true of IT or HR directors or even operational directors, as other examples). Moreover, a mid-level finance manager might be very reluctant to challenge the views of his/her boss in public (indeed, might see it as career suicide). Conversely, performance analysts might have the independence but not the authority required to influence the scorecard design process or to challenge senior managers.

Interview Questions

Senior management interviews should contain two or three questions for each perspective (or themes) and take no longer than one hour. Regardless of functional position, leaders answer the same set of questions. It is not the interviewer’s role to enter a debate, but simply to collect, and then synthesize, responses.

Questions should be open and not closed and focus should be on the strategic priorities and capabilities. Crucially, it is important that, in these sessions, there is no discussion on KPIs or even initiatives. The danger here is that what is getting measured now, or what major initiatives are underway, will shape the choice of objectives, which is clearly back to front. This interview is about clarifying strategic priorities and identifying the capabilities that the organization has or must develop, and nothing else.

What are the financial/funder objectives?

Who are the customers, and what are their objectives?

What internal processes support the financial and customer objectives and what capabilities do we need to develop these processes?

What culture, competencies, and technology support the internal objectives and what capabilities do we need to develop these processes?

The collated responses form the key input to the Strategic Change Agenda.

The Benefits of Anonymity

For interviews to be valuable, they typically should be anonymous. This ensures that key personnel can express their views in a safe and confidential environment. They can say what they really think! As one practitioner, interviewed for the book Doing More with less, stated, the individual and anonymous interviews proved, “a great opportunity for them to ‘get things off their chest’ in a safe environment and setting” [4].

Interview Outcomes

What tends to emerge from these interviews is a general, high-level understanding of the critical capabilities and relationships that an organization must master to deliver to the strategy. Where there is usually some divergence is regarding the priority capabilities and relationships—unsurprising, as functional heads typically see their own outcomes as well as processes and learning requirements as taking precedence.

Through one-to-one interviews, the external facilitator gains a clear picture as to how individual senior managers view the drivers of organizational strategic success—what they agree upon and where they differ.

Another benefit of having already done individual interviews, and cited by another practitioner interviewed for the book Doing More with less, was that, “as the external facilitator presented a consolidated view of the senior managers’ views and not their individual responses, the leaders felt more comfortable in giving full and frank feedback, which strengthened the work” [5].

Based on these interviews, the facilitator prepares a first draft Strategic Change Agenda (see below). But note that, during this phase (and throughout the complete scorecard creation process), a small staff team (perhaps two or three in total drawn from different functions, who should be selected for their commitment to collaborative workings as much as their domain expertise) should be involved. This is particularly important when engaging an external consultancy, as the organization must be able to manage scorecards without external support once the consultancy period is over—this should be a contractual deliverable in any consultancy project.

Devolved Interviews

Purchasing Agency Case Illustration

As well as senior management interviews, it is sensible to secure input and comments from lower-level managers/teams. This is critical for securing buy-in from those that must actually implement the strategy (and thus overcoming the danger of building and mapping a plan and throwing it over the wall for others to execute). A good example of doing this well comes from the North West Collaborative Commercial Agency (NWCCA), which is the collaborative purchasing agency for the UK National Health Service (NHS) trusts in the North West of England (Greater Manchester, Merseyside, Cheshire, Cumbria, and Lancashire).

When building the Strategy Map in 2009, three levels of interviews took place. At the senior manager/director level, focused one-to-one interviews were held to consider the entire strategy and to gauge each manager’s take on why the organization exists, the priority areas in which it must excel, and the underpinning enablers of performance.

Facilitated focus group sessions for functional groups such as finance, operations, IT, and marketing followed. These sessions focused on what the functional areas must do to support the strategy as well as securing their views on mission-critical strategic goals, performance enablers, and so on.

A further interview phase involved selected external stakeholders as well as non-executive board members. Discussions centred on all objectives and outcome targets and not on the internal drivers of performance.

The data from the three interview streams informed the draft Strategy Map, which was finalized at a feedback workshop, attended by most of the interviewees. Those staff members that couldn’t attend the workshops were invited to provide written feedback via e-mail. That said, the composition of the final map was the decision of the executive leadership team. This is right and proper, as they have ultimate responsibility for delivering the organizational strategy [6].

A Strategic Change Agenda

Something we have noticed over the years is that despite the growing number of sophisticated tools now available for strategy management, some of the most useful are the simplest; one of which is the Strategic Change Agenda, for which the senior management interviews are the key input. In our work with organizations, we encourage the spending of more time on shaping the change agenda than on choosing the objectives. From a well thought out Strategic Change Agenda, the objectives just fall out. They become blatantly obvious.

Strategic Change Agenda

Case Illustration: FBI

FBI Strategic Change Agenda

He added that as a key strategic shift, agents had to make the mind-set and cultural switch from being secretive to working outside of traditional operational silos and to become contributors to integrated teams. “In even more of a discontinuity, the FBI had to learn to share information and work collaboratively with other federal agencies to prevent incidents that could harm US citizens.”The change agenda [which the FBI called Strategic Shifts] indicates that the agency would have to undergo a major shift from being a case-driven organization (reacting to crimes already committed) to becoming a threat-driven organization (attempting to prevent a terrorist incident from occurring).

Dr. Robert Kaplan

The change agenda emerged from extensive dialogue throughout the organization, inviting all levels of the FBI to participate in setting the goals for the new strategic direction, which contributed to widespread understanding and support for the new strategy that followed. Kaplan explained that Director Mueller carried a laminated FBI strategic change agenda chart with him whenever he visited a field office. “If agents expressed skepticism about or resistance to the new initiative and structures he reminded them, using the single-page summary, why change was necessary.” [7]

This is one benefit of a Strategic Change Agenda. It is a powerful communication tool, explaining how the strategy will be implemented and how far the organization is away from the desired state.

The Strategic Change Agenda helps the leadership team articulate and communicate the cultural, structural and operating changes necessary to transition from the past to the future.

FBI strategy map

This translated into the objective “enhance relationships with law enforcement and intelligence partners.” The scope shift from domestic to global was captured through “enhance international operations.” As a further example, the as is, for information sharing was “restrict: and share what you must,” while the to be read, “share: and restrict what you must.” This was actualized through the objective, “intelligence dissemination and integration.”

Parting Words

Strategic Change Agenda, arranged from four perspectives

In addition to the value in identifying objectives, the rich conversations that happen here enable an initial understanding of the causal relationship between the perspectives. Also provided is clarity around where work needs to be done (in strategic initiatives and process improvements) to move from the “as is,” to the “to be,” and so close the value gap and deliver to the quantified vision. Indeed, as many participants have said to us—and this applies to this stage, as well as to building the actual Balanced Scorecard System, “the quality of the conversations we have as a senior team are as important as the scorecard we develop.”

In the next chapter, we discuss strategy mapping in detail.

Panel 1: War Games

A tool that is increasingly deployed is war games, which is useful to run when new strategies are being developed and when major strategic reactions need to be made (so a valuable counter to disruption). A war game helps uncovering hidden weaknesses—the organizations and its competitors—and so formulating best-course options.

- 1.Determine who the key stakeholders are

Identify the key stakeholders

Develop the storyline: What are we going to simulate? What is the plan we want to test? (Alternative scenarios prepared for the war game session).

Detailed research and modelling of the environment and the behaviours of each stakeholder

- 2.

Develop a briefing book for participants

Develop a briefing book with the baseline of information about each stakeholder that will be represented in the game (pre-reading briefing book created and distributed in advance to the participants).- (a)

Industry overview

- (b)

Stakeholders profiles (background, geographical footprint, business segments, market analysis, financial highlights and key indicators, strategy directions, etc.).

- (a)

- 3.Prepare war game session

Select the right people to play the game and brief them extensively on the role they will be play and the storyline.

Identify core questions to be addressed through the game

A war game is run over several rounds and involves teams representing different key stakeholder groups: competitors, customers, regulators, suppliers, media, employees, the media, and so on. In round one, stakeholders are presented with the situation (typically one fact and date, such as “we are launching a new product line on such a date”). All teams prepare their response, then interact with each other to ask questions, lobby, partner, and the like.

Following a debriefing at the end of round one (and after teams have presented on how they will respond) the strategy can be adapted, and further rounds conducted until the most robust strategy is identified—and with alternatives available if things don’t quite work out that way!

This is an important point, in today’s world, in which we have passed through the technology “tipping point.” Accurate predictions of what the future competitive landscape will look like are fraught with challenges. As one telecoms director said to one of the authors, “we struggle to figure what the world will look like six months from now.”

Scenario planning is a similar, well-established tool for painting various “scenarios,” of what the future might look like. To restate a key message of this book—in strategy execution, pay as much as attention to what’s going on in the external world as to what’s happening internally.

Panel 2: The OOLA Loop

In an interview for this book, John A Gelmini, Marketing, Innovation, Strategy and Partnerships Director, OS International Plc. (Consultancy, Innovation and Partnerships Division) described the value of the OOLA Loop as “for gaining future focus, optimize known risks and create temporary, ‘windows of opportunity.’”

Gelmini explains that agility and the ability to metamorphose at speed need to support the unfolding strategy, so to cope with competitive shocks and “Black Swan” events (an event or occurrence that deviates beyond what is normally expected of a situation and is extremely difficult to predict).

“This involves incorporating the military doctrine of the OODA Loop, which emerged from military strategist and United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd’s book ‘A discourse on winning and losing,’ [8], which borrowed heavily from Sun Tzu’s ‘Art of War,’ [9] and Iyamoto Musashi (c. 1584 – June 13, 1645) ‘Book of 5 Rings.’ [10] and was applied in Korea, Vietnam and the 1st Gulf War.”

The phrase OODA loop refers to the decision cycle of observe, orient, decide, and act, which was originally applied to the combat operations process, often at the strategic level in military operations.

It is now also often applied to commercial operations and learning processes. The approach might be powerful for the digital age and the requirement, as we stress throughout this book, to meld strategy management into a single, integrated process and with a continuous learning look. With the OODA Loop, all decisions are based on observations of the evolving situation tempered with implicit filtering of the problem being addressed. The observations are the raw information on which decisions and actions are based and favours agility over power in dealing with human opponents in any endeavour.

Observe—ideally without competitors knowing what you have seen and worked out.

Orienting yourself and your position relative to what competitors are doing, again, without them realizing what your next move might be.

Deploy means assembling your marketing collateral, salesforces, and social media campaigns, and readying them for action without their knowing what you are doing.

Action—swift, precise, and unexpected. “The process is undertaken at speed which is varied to disorient the competitor so that he or she is reacting to events which have already transpired and is repeated again and again so the strategy is executed in a series of hammer blows which cannot be countered fast enough or at all” explains Gelmini.

Self-Assessment Checklist

The following self-assessment assists the reader in identifying strengths and opportunities for improvement against the key performance dimension that we consider critical for succeeding with strategy management in the digital age.

Self-assessment checklist

Please tick the number that is the closest to the statement with which you agree | ||||||||

7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

My organization has a well-quantified, long-term vision statement | My organization does not have a quantified, long-term vision statement | |||||||

My organization has a well-quantified, mid-term vision statement | My organization does not have a quantified, mid-term vision statement | |||||||

We have clear mid-term goals | We do not have clear mid-term goals | |||||||

My organization is very good at external environmental scanning | My organization is very poor at external environmental scanning | |||||||

My organization is very good at internal environmental scanning | My organization is very poor at internal environmental scanning | |||||||

The annual environmental scan is a relatively quick process | The annual environmental scan is a slow process | |||||||

We have clearly defined the “value gap” between present performance and future targets | We have not clearly defined the “value gap” between present performance and future targets | |||||||

When updating the strategy, we gain input through anonymous interviews with senior executives | When updating the strategy, we do not gain input through anonymous interviews with senior executives | |||||||

When updating the strategy, we create a Strategic Change Agenda or similar | When updating the strategy, we do not create a Strategic Change Agenda or similar | |||||||