THE FAILURE OF

INTELLIGENCE

By all conventional measures of power and peril, the Japanese threat in 1941 and that of Al Qaeda and Islamist terror in 2001 had very little in common. Imperial Japan was a nation-state with a huge, highly mechanized army and navy. Beginning in 1933 it had increasingly isolated itself from the international community after being condemned by the League of Nations for seizing Manchuria and, in angry response, withdrawing from that world organization. Since 1937, it had been mired in all-out war with China—occupying that country’s vast, populous seaboard while tied down by Nationalist and Communist forces in the interior. Japan’s decision to “move south” and take over colonized Southeast Asia (French Indochina, the Dutch East Indies, British Hong Kong, Malaya and Burma, the U.S.-controlled Philippines)—the fatal decision that prompted the preemptive attack on Pearl Harbor—was motivated primarily by a need for guaranteed access to strategic resources necessary to carry on the war in China.

Initially, Japan’s aggression against China relied heavily on imports of steel, fuel, and the like from the United States. (Japan rather than China was America’s major Asian market.) As the war dragged on and pro-Chinese domestic pressures forced the Roosevelt administration, in conjunction with other colonial powers, to incrementally tighten restrictions on such exports, the Japanese responded with cries of “economic strangulation” and “ABCD encirclement” (American, British, Chinese, and Dutch). While it might seem the epitome of perversity to argue that China was encircling Japan, this notion seemed plausible in Japanese eyes—where the “C” in ABCD could just as well have stood for “communism.” Much Japanese war propaganda in the 1930s focused on the rise of communist influence in China. Where Americans and Europeans placed Japanese expansion in the context of a “Yellow Peril,” Japanese ideologues were fixated not merely on the “White Peril” of European and American imperialism, but also the “Red Peril” of Soviet-led international communism.

Even after the outbreak of open war between Japan and China, the anticommunist exhortation had considerable appeal among Western diplomats and policy makers. Ambassador Grew in Tokyo was so insistent in stressing the importance of Japan as a “stabilizing power” in Asia, for example, that he was eventually forced to defend himself against accusations of appeasement. China—still saddled in 1941 with unequal treaties and foreign concessions associated with nineteenth-century European, American, and Japanese imperialism—was unstable and in turmoil when all-out war broke out in 1937. Revolutionary change was in the air, and antiforeign sentiment animated both Communist forces under Mao Zedong and the Guomindang (Kuomintang) under Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek). In this turbulent ideological struggle, virtually all parties in China rallied support under the flag of “liberation.”

Although Japan’s relations with the United States were severely strained and worsening by 1941, on the eve of Pearl Harbor the two nations were still talking in Washington in an attempt to resolve their differences. From the U.S. perspective, the most critical issues were Japan’s aggression in China, its expansionist ambitions in Southeast Asia, and its alliance with Germany and Italy, dating from September 1940. The Japanese, on their part, demanded that the United States abandon its embargoes on strategic exports and stop supporting the Chinese resistance led by the Nationalist regime operating out of Chongqing (Chungking), deep in China’s unconquered interior.21

By late November, both sides concluded that these negotiations had failed. In a soon-famous diary entry on November 27, Secretary of War Henry Stimson recorded that Secretary of State Cordell Hull informed him he had broken off talks with Japan. “I have washed my hands of it,” he quoted Hull saying, “and it is now in the hands of you and [Secretary of the Navy Frank] Knox—the Army and the Navy.”22 Two days earlier, the Japanese attack force had already set out for Pearl Harbor from its secret training base in the Kurile Islands. The armada numbered some sixty warships, including six aircraft carriers, and maintained strict radio silence—a ghost fleet embarked on a mission U.S. war planners had long talked about and even planned for but no one actually took seriously.

While high U.S. officials recognized that war was imminent, they expected it to take the form of an invasion of Western colonies in Southeast Asia—particularly the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), probably British holdings in Malaya including Singapore, and possibly America’s own Asian enclave, the Philippines. Within Japanese officialdom, the Pearl Harbor attack plan itself was a well-guarded secret but not—as made clear by Gordon Prange, who devoted several decades to historical study of the attack—a “supersecret.” As the actual date of attack drew near, an increasing number of naval officers on the task force itself had to be brought in on the secret. So did navy and army officers engaged in planning the complex and simultaneous “Southern Operation” aimed at seizing all of Southeast Asia, including the Philippines. In the cabinet, the highest organ in Japan’s executive branch, on the other hand, knowledge of the Pearl Harbor plan was highly restricted. Although Prime Minister Hideki Tojo (an army general who served simultaneously as minister of war) knew of it, he later claimed he was not privy to the actual operational details. The emperor was briefed beforehand. The Foreign Ministry was not, nor by extension were the envoys negotiating with the State Department in Washington.23

It was Japan’s intention to inform the United States that it was breaking off relations moments before the attack. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, who conceived and oversaw the Pearl Harbor operation, insisted on this as a matter of honor. With this in mind, the negotiators in Washington were given strict instructions about exactly when this final message should be delivered. As fate would have it, with its propensity for mixing small mischief with great catastrophes, clerical ineptitude in the Japanese embassy delayed the decryption, translation, and delivery of this note. It was conveyed to Secretary of State Hull shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack was underway. While announcing termination of relations, the note said nothing about war.

In practice, this bungled communication did not matter. The United States had cracked Japan’s diplomatic code in August 1940 (but, prior to December 7, 1941, not its basic army and navy codes).24 Top-level officials thus already knew that relations were being broken off and Japan was poised to embark on a new stage of military expansion. Precisely where the next attacks would come was the question; and on this—on who in the top ranks of U.S. civilian and military leadership really knew or should have known what, and why the military was caught so disastrously unprepared—oceans of ink would be spilled in the years and decades to come.

Japan’s objective in the Pearl Harbor attack was to cripple the U.S. Pacific Fleet and thereby thwart an immediate response to the advance into Southeast Asia. This was but one of many offensive actions in a breathtakingly complex, “phase one” coordinated strike on some twenty-nine separate targets with an initial force of two thousand aircraft, 160 surface ships, and over sixty submarines.25 Any psychological considerations of how the Americans might be expected to respond usually emerged as marginal afterthoughts. Thus, in a letter dated January 7, 1941—when he was still urging adoption of his audacious proposal to attack Pearl Harbor, well before any concrete planning had been initiated—Admiral Yamamoto put his case to the navy minister in these terms:

The most important thing we have to do first of all in a war with the U.S., I firmly believe, is to fiercely attack and destroy the U.S. main fleet at the outset of the war, so that the morale of the U.S. Navy and her people goes down to such an extent that it can not be recovered.

Casual and shallow as such thinking may have been, it became enshrined in basic planning. The major document outlining projections for “hastening the end of the war,” approved a few weeks before Pearl Harbor (on November 15), expressed hope that Japan’s early military successes would “destroy the will of the United States to continue the war.” What Samuel Eliot Morison later ridiculed as the “strategic imbecility” of the Pearl Harbor attack was thus present start to finish in this blissful retreat into wishful thinking.26

Personally, Yamamoto opposed initiating hostilities with the United States. A charismatic veteran of the old navy (as a young officer, he was wounded in the celebrated Battle of Tsushima in 1905, when Japan destroyed the Russian fleet in the Russo-Japanese War), he had spent time at Harvard after World War I and two terms as a naval attaché in Washington in the 1920s. He opposed tightening Japan’s relations with Germany between 1936 and 1940 on the grounds that this would lead to war with America, and as late as October 1941 was still writing privately that the decision for war “was entirely against my private opinion.” On more than one occasion, Yamamoto made it clear that the best one could hope for was to keep U.S. forces at bay for six months or a year while Japan consolidated control over the southern region.27

As an officer and a loyal subject of the emperor, however, Yamamoto accepted the decision to launch war if diplomacy failed—and devoted himself to making that war a success. Against strong internal opposition (particularly from the old-guard “battleship admirals”), he persuaded his superiors that a preemptive strike against the U.S. fleet from aircraft carriers was not only essential to buy time, but also feasible; and, on the latter score, the stunning tactical success at Pearl Harbor proved him correct. In war games conducted in September 1941, the Japanese navy had concluded that they might well lose two or three of their six carriers. Seamen and pilots in the attack force anticipated dying and wrote wills and farewell messages to kin and loved ones on shipboard on the eve of the attack. As it turned out, Japanese losses amounted to only twenty-nine aircraft, five midget submarines, and sixty-four men (fifty-five pilots and nine submariners), who were killed in action.28

Tactically brilliant as it may have been, Yamamoto’s brainchild was a psychological blunder of fatal proportions. Contrary to weakening American morale, it mobilized the country under the “Remember Pearl Harbor—Keep ’em Dying” war cry that resonated until Japan’s navy had been sunk, its great cadre of experienced pilots killed, its army destroyed or simply stranded to starve on isolated Pacific islands, and its homeland torched, first with firebombs and finally with nuclear weapons.

All this stands in sharp contrast to 9-11. Japan was a major power engaged in conventional warfare. Its targets were purely military, and psychological considerations at best an afterthought—in contrast to their central place in the terrorist agenda. Hawaii itself was marginal in American consciousness at the time: a remote, exotic territory annexed in 1898 that did not become a U.S. state until 1959. It was not until the spring of 1940 that Pearl Harbor even became the major base of the Pacific Fleet, which until then had been berthed in San Diego.

“Weapons of mass destruction” were certainly available in superabundance to the protagonists in World War II. One need only consider the toll of the war globally—at least sixty million dead—to be reminded that mass slaughter did not require nuclear weapons. But arsenals of the time were nonetheless rudimentary when compared to the aircraft, warships, missiles, “smart weapons,” nuclear devices, and chemical and biological weapons of the twenty-first century. Similarly, codes and code breaking did play an important role in intelligence gathering prior to Pearl Harbor, and much more so during the war that followed—but, again, at levels that seem elemental when compared to the technological sophistication of present-day intelligence gathering and the gargantuan security agencies that have grown like dark forests around this. It was in considerable part the debacle of December 7 that focused attention on elevating the collection and analysis of foreign intelligence after World War II. As William Casey, director of the Central Intelligence Agency in the 1980s, put it, the CIA was created in 1947 “to ensure there will never be another Pearl Harbor.”29

Unlike imperial Japan with its racial homogeneity, fierce nationalism, and ponderous war machine, Al Qaeda was a loose network that crossed national and ethnic boundaries. Although its base in Afghanistan was important for training terrorists, the organization did not rely on state sponsorship. Possessing neither army nor navy nor massive firepower, its warriors were volunteers driven by the political and religious fervor of jihad, or holy war. Operating out of remote and hidden places, Osama bin Laden exploited satellite television and cyberspace to convey his messages not merely to terrorist operatives, but also to the Arabic-speaking world at large. He issued his first “Declaration of Jihad against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Sanctuaries” (Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia) in August 1996, and in February 1998 joined four other Islamist radicals in declaring a second fatwa against “the soldiers of Satan, the Americans, and whichever devil’s supporters are allied with them.”30

Since 1991, the 1998 screed charged, “America has occupied the holiest parts of the Islamic lands, the Arabian peninsula, plundering its wealth, dictating to its leaders, humiliating its people, terrorizing its neighbors and turning its bases there into a spearhead with which to fight the neighboring Muslim people.” The fatwa singled out Iraq, where “over one million” had already died as a consequence of U.S.-led economic sanctions imposed through the United Nations after the first Gulf War, as the major target of future U.S. aggression. Predictably, this declaration of war went on to declare that the religious and economic objectives of the Americans also served “the interests of the petty Jewish state, diverting attention from its occupation of Jerusalem and its murder of Muslims there.”

Following the February 1998 fatwa, bin Laden elaborated on why the United States had been singled out for attack and told an ABC television reporter, “We anticipate a black future for America.” Shortly after this, on August 7, Al Qaeda directed simultaneous suicide-bombing attacks on the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, killing over two hundred people. These were the first anti-American atrocities unequivocally connected to Al Qaeda, and the Clinton administration retaliated by launching cruise missiles against a training camp in Afghanistan where bin Laden was thought to be, and subsequently offering a $5 million reward for information leading to his capture. The code name of the unsuccessful missile strike was, in retrospect, a fair reflection of superpower hubris in a new world of asymmetric conflict: “Operation Infinite Reach.” Two years later, in October 2000, suicide bombers in a small boat severely damaged the destroyer USS Cole berthed in Aden, Yemen, killing seventeen American seamen.31

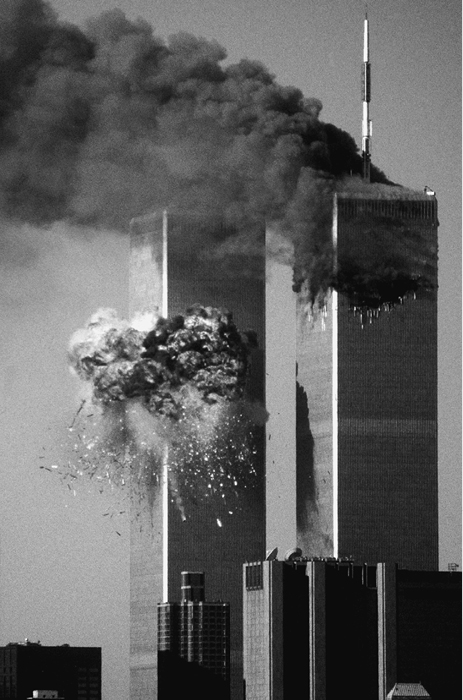

12. September 11: Flight 175, the second hijacked plane, approaches the burning World Trade Center.

U.S. counterterrorism analysts, collaborating with Saudi Arabia, first discovered the size, shape, and name of bin Laden’s operation in the spring of 1996, shortly before the first fatwa. As Richard Clarke, head of the National Security Council’s interagency Counterterrorism Security Group from 1992, later wrote, this network was perceived by its organizers to be “the necessary base for the edifice that would become a global theocracy, the great Caliphate.”32 With the 1998 fatwa, bin Laden and his confederates publicly turned their focus onto America as the primary enemy, and U.S. intelligence in turn placed Al Qaeda’s leader clearly in its sights.

13. The flaming moment of impact at the south tower of the World Trade Center.

Even Al Qaeda’s subsequent flamboyant attacks on the U.S. diplomatic and military presence overseas, however, offer scant analogy to imperial Japan and its road through China to Pearl Harbor. Al Qaeda remained organizationally fragile and torn by internal disagreements as the millennium approached and passed. And the theocratic empire bin Laden vaguely imagined, and modes of violence at his command, differed in almost every way from Japan’s territorial objectives and war-making capabilities. The stunning, almost freakish success of the 9-11 attacks changed all this, giving the bin Laden network both notoriety and an appeal among many disaffected Muslims and Arabs that it never previously possessed. Where Pearl Harbor marked the beginning of the end for imperial Japan, September 11 signaled the end of the beginning for Al Qaeda.

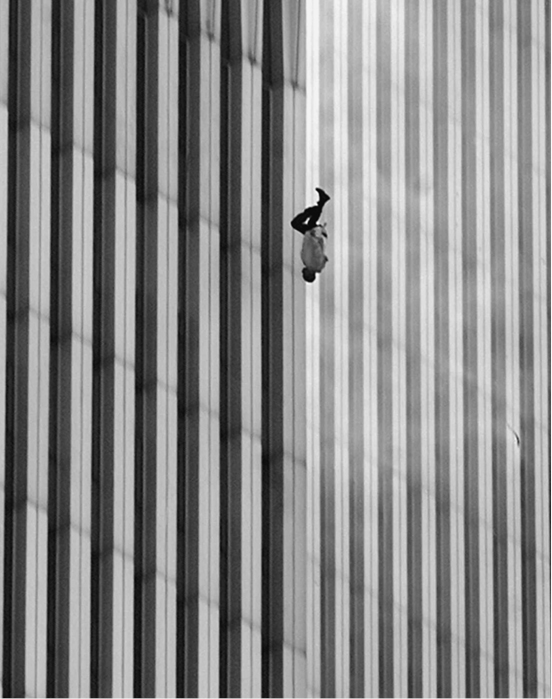

14. Richard Drew’s “Falling Man” photograph captured the double shock of seeing people throw themselves from the burning towers to escape the inferno.

Unlike Pearl Harbor, the targets of the terrorists—the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and probably the White House or Congress (by the fourth, unsuccessful hijacked plane)—were not conventional military targets. Although the numbers killed in 1941 and 2001 were fairly close (some twenty-four hundred at Pearl Harbor and slightly more than three thousand on September 11), those who perished in 2001 were largely civilians and represented, as Lawrence Wright has reminded us, some sixty-two countries and “nearly every ethnic group and religion in the world.”33

15. A fireman in the ruins of the World Trade Center on September 15 signals for ten more rescue workers.

Although Al Qaeda’s war of choice was as audacious in its way as that of the Japanese aggressors six decades earlier, it was not preemptive in a strict military sense and had nothing to do with buying time. The September 11 attack was an unprecedented exercise in psychological warfare that struck not at the periphery of the United States, but at its heartbeat in New York and Washington. It targeted not only the symbolic institutional essence of the American state—finance, the military establishment, and democratic government—but the nation’s core values as well. Bin Laden, always chillingly direct, made this clear in interviews shortly after September 11, in which he predictably placed the attacks in the context of “self-defense,” of revenge, and of overthrowing the secular values of the infidel West itself.

In a video scheduled for broadcast on Al Jazeera television on October 7, when retaliatory U.S. bombardment of Al Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan commenced, for example, bin Laden declared that “what America is tasting today is but a fraction of what we have tasted for decades. For over eighty years our umma [Islamic nation or community] has endured this humiliation and contempt. Its sons have been killed, its blood has been shed, its holy sanctuaries have been violated, all in a manner contrary to that revealed by God, without anyone listening or responding.” Several weeks later, he gave a long interview to Al Jazeera (not aired until January 2002) in which his scorn for “this Western civilization, which is backed by America” was filtered through the ruins of the World Trade Center: “The immense materialistic towers, which preach Freedom, Human Rights, and Equality, were destroyed.”34

In almost every imaginable way, 9-11 shocked, mesmerized, and electrified the world—abetted by technologies of mass communication that were undreamed of in 1941. Apart from a few photographs of dark clouds of smoke billowing from crippled warships, no one outside Pearl Harbor itself really “saw” the attack. Even later “documentary” film footage, such as in John Ford’s 1943 Academy Award–winning December 7th, was mostly contrived. By contrast, almost everyone in the developed world was able to bear eyewitness—over and over and over again—to September 11.

Despite such substantive differences, Pearl Harbor and September 11 pose the same question: why was the United States caught by surprise? The hostility of both adversaries was amply clear beforehand, and had deep roots. In each instance, codes had been broken and intelligence experts were reading secret communications. It was obvious in both cases that something spectacular was going to happen, and soon. The only question was, where?

The most persuasive explanations as to why the United States was so woefully unprepared in both cases turn out to be similar. They involve, first, bureaucratic structures and procedures that abetted human error, and, second, a profound failure of imagination.

In the wake of Pearl Harbor, Americans did what people usually do in response to man-made catastrophes. They focused on the immediate disaster (rather than the deeper causes that drove events to this pass), singled out scapegoats, played partisan politics to a greater or lesser degree, launched official investigations, drew largely predictable conclusions, and proposed bureaucratic reorganization.

Between December 1941 and July 1946, the United States conducted no less than nine investigations aimed at determining responsibility for the intelligence failure. Seven were initiated by the executive branch during the war and one just afterwards; these inquiries were conducted by or in close collaboration with the military. The most extensive investigation involved hearings sponsored by both houses of Congress after Japan’s surrender. Running from November 15, 1945, to July 15, 1946, the hearings resulted in a transcript that totaled roughly a million words and was issued in forty parts. The final report, well over five hundred pages long, included a majority opinion endorsed by eight committee members and a minority report submitted by two members. These documents quickly became a basic source for subsequent commentaries.35

The first and last investigations involved scapegoating of a particularly harsh nature. In January 1942, the navy and army commanders in Pearl Harbor, Admiral Husband Kimmel and Lieutenant General Walter Short, were found guilty of “dereliction of duty”—a grievous charge that momentarily deflected scrutiny away from personal and procedural failures in Washington. (General MacArthur, who let his air force in the Philippines be caught on the ground nine hours after Pearl Harbor, unaccountably escaped such disgrace and went on to command the Army’s Pacific campaigns.)36 Although the charge against Kimmel and Short was tempered in the majority report of the postwar hearings, which found them guilty of “errors of judgment and not derelictions of duty,” their careers and reputations were ruined.

Politically, the postwar hearings offered the out-of-power Republican Party a conspicuous opportunity to repudiate the bipartisanship that had lasted until near the end of the war and to argue that President Roosevelt (who died in April 1945, four months before Japan’s defeat) and his “war cabinet” bore heavy responsibility for the disaster. In magnified form, these arguments have persisted to the present day. In the early postwar years they inspired a body of writings identified as Pearl Harbor “revisionism,” or the “backdoor to war” thesis, arguing that Roosevelt desired war in order to come to the aid of England against Nazi Germany. To this end, the argument proceeds, he deliberately provoked the Japanese and ignored their overtures to work out some sort of modus vivendi. In 1982, the popular author John Toland published a bestseller titled Infamy that turned Roosevelt’s famous phrase on its head by elaborating on this revisionist thesis and suggesting that the United States had possessed hitherto neglected intelligence explicitly pointing to Pearl Harbor. More than Japan, in Toland’s view, it was America’s behavior in 1941 that was shameful.37

The backdoor-to-war thesis is a dense and contentious subject and deserves attention, but such conspiracy theories are not persuasive. Despite their partisan undercurrents, even the congressional hearings identified the larger problem to be one of institutional structures and procedures, within which individual failures took place. This argument has been embellished at length in the writings of academics such as Roberta Wohlstetter and Gordon Prange, the latter of whom conducted prodigious bilingual research on the attack. As Prange’s research associates summed it up (Prange died in 1980 before his exhaustive studies saw the light of publication), his conclusion after decades of research was this: “There were no Pearl Harbor villains; there were no Pearl Harbor scapegoats. No one directly concerned was without blame, from Roosevelt on down the line. They all made mistakes.” Wohlstetter, whose dry approach focused more tightly on systems analysis, argued that these mistakes occurred because the entire apparatus of intelligence gathering, analysis, and dissemination was flawed.38

One of Wohlstetter’s key concepts in explaining the difficulties inherent in making order out of a torrent of competing intelligence signals was “noise.” (One chapter in her influential 1962 study is titled “Noise in Hawaii” and another “Signals and Noise at Home.”) At one point she borrows someone else’s phrase to describe the cacophony of ambiguous signals as “buzzing and blooming confusion.” In current discourse the essentially synonymous buzzword for noise is “chatter.” Condoleezza Rice, serving as the national security adviser in 2001, for example, blamed the failure to identify warnings of the 9-11 attacks partly on the fact that there was “a lot of chatter in the system.” We founder in words; and the more words intercepted, the greater the prospects of being overwhelmed.39

Monday-morning quarterbacking, the noise argument holds, enables us to revisit collected intelligence and single out signals or messages belatedly known to be significant. It certainly enables us to ignore the fact that in the weeks leading up to Pearl Harbor, “almost everyone” in the U.S. government from Roosevelt down was primarily absorbed in developments “in the Atlantic and European battle areas”—just as in the weeks and months prior to 9-11 the Bush administration was preoccupied with a range of strategic priorities other than terrorism, led by missile defense and relations with China, Russia, Europe, and Eastern Europe.40 Much of the heated debate over responsibility for the failure at Pearl Harbor focused on such exhumed, decoded messages. Why were they not pursued more vigorously? Was it not clear what they portended? (Usually, it was not.)

What impedes effective analysis, absent the benefit of hindsight, however, goes beyond noise in the mere sense of volume per se. In the uncertain and rapidly changing world of 1941, signals often reflected indecision, vacillation, or rapid change in the enemy’s policy process itself, and thus might be inherently contradictory and confusing. Even more problematic, the bureaucratic system through which information was processed in 1941 was not only rigid and compartmentalized, but also riddled with turf wars. The majority report that emerged from the congressional hearings in 1946, for example, called attention to “supervisory, administrative, and organizational deficiencies” in general and focused on the “pitfalls of divided responsibility” within the military in particular. “The whole story of discussions during 1941 with respect to unity of command,” the majority found, “is a picture of jealous adherence to departmental prerogatives and unwillingness to make concessions in the interest of both the Army and Navy.”41

The minority report, which directed its harshest criticism at the president and his top aides, concluded along similar lines that “the failure of Washington authorities to act promptly and consistently in translating intercepts, evaluating information, and sending appropriate instructions to the Hawaiian commanders was in considerable measure due to delays, mismanagement, non-cooperation, unpreparedness, confusion, and negligence on the part of officers in Washington.” “Dysfunction” was not part of the operative jargon of those immediate postwar years, but, as with the majority report, the minority’s summary conclusion was generic and could be applied to the September 11 catastrophe with little change: “The tragedy at Pearl Harbor was primarily a failure of men and not of laws or powers to do the necessary things, and carry out the vested responsibilities. No legislation could have cured such defects of official judgment, management, cooperation, and action as were displayed by authorities and agents of the United States in connection with the events that culminated in the catastrophe at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.”42

Later postmortems of the Pearl Harbor attack concurred with this picture of organizational disarray. There was “no single person or agency in Washington,” Wohlstetter concluded, “that had all the signals available at any one time.” Communication between Washington and Hawaii was “rudimentary.” Frequently—most significantly, at the critical moment in late November when the State Department was breaking off negotiations with Japan—Secretary of State Hull acted “without consulting the Army or Navy.” The Army and Navy themselves maintained “respectful and cordial, but empty, communication” between one another, both in Washington and in Hawaii. Such interservice impediments to analysis and communication, moreover, were also to be observed in “intraservice” rivalries.43

Beyond this, secrecy itself was a double problem. On the Japanese side, Pearl Harbor was an ultrasecret operation to which the vast majority of even top-level military officers and civilian officials were not privy. The Foreign Ministry as a whole was out of the loop; and since the only major Japanese code American cryptographers had broken in 1940 was the diplomatic code (known as “Purple”), intercepted materials pertinent to the military’s plans were at best oblique. They involved, that is, instructions to diplomats in Washington, Hawaii, Berlin, or elsewhere that Foreign Ministry officials in Tokyo had been asked to make but did not fully comprehend themselves.

More problematic, however, was the conundrum inherent in handling secret intercepts, for to share such sensitive materials threatened to expose the biggest secret of all: the fact that the United States was reading Japan’s diplomatic traffic. The more the decoded intercepts were disseminated within the government and acted upon, that is, the greater the danger that the Japanese would figure out that “Purple” had been broken—and proceed to change the code. The name of the U.S. code-breaking (and translation) operation was “Magic”—and one did not casually share the fruits of such magic with others. The congressional majority report of 1946 called attention to this with a rare touch of irony. “So closely held and top secret was this intelligence,” the report observed, “that it appears the fact that the Japanese codes had been broken was regarded as of more importance than the information obtained from decoded traffic.” Wohlstetter reached a similar conclusion in noting that “the effect of carefully limiting the reading and discussion of MAGIC, which was necessary to safeguard the secret of our knowledge of the code, was thus to reduce this group of signals to the point where they were scarcely heard.” Secrecy, in an ultra-clandestine world, easily becomes a trap.44

These postmortems of unpreparedness for Pearl Harbor foreshadow the analysis of intelligence failure offered in The 9/11 Commission Report, which was released with fanfare in July 2004. The devil may be in the details, and the details in both cases are engrossing. When it comes to recommended reforms, however, the diagnosis of the September 11 disaster falls back on much the same generic critique of system dysfunction compounded by negligence that runs through the literature on Pearl Harbor.

The 2004 report, which included a table of fifteen major intelligence agencies, commented harshly about inter- and intra-agency rivalries among and within the CIA, FBI, National Security Agency (NSA), and Defense Department “behemoth.” Its indictment touched all the familiar bases associated with bureaucratic compartmentalization: “duplication of effort,” “civilian-military misunderstandings,” administrative “stovepipes” and “turf” wars, “structural barriers to performing joint intelligence work,” “divided management of intelligence analysis.” As with Pearl Harbor, the 9-11 intelligence failure also was attributed to the culture of secrecy. The NSA, for instance, was condemned for “almost obsessive protection of sources and methods,” but the problem again was system-wide—rooted in “the culture of agencies feeling they own the information they gathered”; in the problems posed by “a ‘need-to-know’ culture of information protection”; in “overclassification and excessive compartmentalization of information among agencies”; in “human or systemic resistance to sharing information”; in a milieu in which “security agencies’ personnel and security systems reward protecting information rather than sharing it.”

Unsurprisingly, the 9-11 Commission’s investigation itself was impeded by the secrecy game. Bureaucratic “stonewalling” by the White House and others blocked access to critical resources—a problem also encountered by the congressional investigators in 1945–46. The investigation also was constricted by agreement to exclude assessment of individual negligence and accountability in the use of intelligence at the highest levels. From its inception, the commission was committed to producing a unanimous “bipartisan” report, which may have been politically understandable but amounted to a recipe for sanitization.45

Still, even without pursuing the who and why of negligence at top levels, the findings of the bipartisan report were damning. As summarized by Thomas Powers, an incisive analyst of intelligence operations, the commission found that in the nine months preceding September 11, intelligence personnel “had warned the administration as many as forty times of the threat posed by Osama bin Laden, but that is not what the administration wanted to hear, and it did not hear it.”46

Beginning around 2004, a cottage industry of accounts by investigative journalists and angry mid-level officials emerged to supplement the 9-11 Commission’s postmortem and throw sharper light on the distraction and disarray that characterized negligence at the highest levels. Immediately after the Bush administration took office in January 2001, for example, the National Security Council’s counterterror czar Richard Clarke told top incoming officials (including Vice President Dick Cheney, National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, and Secretary of State Colin Powell) that Al Qaeda was at war with the United States, had sleeper cells in the country, and was about to launch a major offensive. On January 25, within a week of the president’s inauguration, Clarke formalized his concern in a letter to his superiors asking “urgently” for a cabinet-level meeting to review this threat. Not until April, however, did the NSC even convene a lower-level “deputies” meeting on the subject—at which Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz dismissed the urgency of the avowed threat. (Clarke quotes Wolfowitz referring to bin Laden as “this little terrorist in Afghanistan.”) The “principals” meeting requested on January 25 did not take place until September 4, exactly a week before the 9-11 attacks, and left Clarke chagrined at what he regarded as “largely a nonevent.”47

Other attempts to focus White House attention on the Al Qaeda threat were similarly stillborn. On July 10, CIA director George Tenet and his counterterrorism chief Cofer Black, alarmed by an increase in intercepts suggesting an approaching “Zero Hour” offensive by Al Qaeda, held an “out of cycle” session with the NSC’s Rice but left this meeting feeling they had not been taken seriously. On August 6, President Bush, vacationing at his ranch in Texas, received a later-notorious President’s Daily Brief from the CIA titled “Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S.” that, again, simply dissolved into the general chatter that held little interest for top officials.48

In the prelude to Pearl Harbor, dysfunction, distraction, and gross negligence at high levels also went hand in hand, but the difference from the Bush administration’s level of inattention is still notable. Roosevelt and his top aides were at least paying attention to intercepted cables and other intelligence pointing to Japan’s war preparations. There was no counterpart in 1941 to the clear signals of impending attack on the United States that were so plentiful in 2001. No alarmed intelligence specialists were begging in vain to be heard in the weeks and months prior to Pearl Harbor, or delivering stark warnings to the president himself. Still, when all is said and done, what remains etched in the historical record is the occurrence of two similar disastrous failures of U.S. intelligence.

THE FINAL CHAPTER of the 9-11 Commission’s report acknowledged resonance between Pearl Harbor and 9-11:

“Surprise, when it happens to a government, is likely to be a complicated, diffuse, bureaucratic thing. It includes neglect of responsibility, but also responsibility so poorly defined or so ambiguously delegated that action gets lost.” That comment was made more than 40 years ago, about Pearl Harbor. We hope another commission, writing in the future about another attack, does not again find this quotation to be so apt.49

Ironically, that quotation was already apt once again when the commission’s report was published, for by July 2004 the United States was mired in a tragedy of its own making in Iraq. Little had been learned from 9-11 about the nature and roots of anti-American grievances and terrorism in the Middle East. “Surprise” had happened again, with a vengeance, as a consequence of this obtuseness. In the aftermath of 9-11, the U.S. government managed to bring about what seemed inconceivable in September 2001: to simultaneously diminish global respect and support for the United States; turn blood-stained bin Laden into a David fighting an armed-to-the-teeth Goliath; inflame Muslim rage throughout the world by precipitating chaos and carnage in Iraq; and, by its extraordinary incompetence, shatter the myth of military invincibility and “infinite reach” that hitherto had buttressed the mystique of American power.

This stupefying accomplishment reflected intensification rather than rectification of the generic intelligence failures that allowed 9-11 to happen in the first place. Turf wars, “stovepiping,” obsessive secrecy, and plain individual arrogance and irresponsibility were only part of the problem, however, and not necessarily the most critical part. Like the unpreparedness of September 11 and December 7, the intelligence fiasco of March 2003 that resulted in tearing apart rather than liberating Iraq also reflected a monumental failure of imagination—a failure that became magnified rather than reduced in the months that followed September 11.