“THE MOST TERRIBLE BOMB IN THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD”

By August 1945, only a handful of Japanese cities had escaped the B-29s and their rain of fire from the sky. Such apparent good fortune was misleading. While U.S. target selection in Japan as in Europe had been left largely to planners in the military theaters, there was one great exception in the air war against the Japanese homeland. Following instructions from Washington, General LeMay’s command left several cities off its lengthy list of “secondary” targets. These were to be held in reserve for a qualitatively new level of terror.

The new level of terror was the atomic bomb, and the cities selected as potential targets by the top-secret “Interim Committee” that decided whether and how to use the new weapon were Kyoto, Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and, belatedly, Nagasaki. Kyoto—Japan’s ancient capital and the site of many of its greatest religious, cultural, and architectural treasures—was later dropped from the list at the urging of Secretary of War Henry Stimson. Stimson had visited and been charmed by the old capital in the 1920s, and also feared that attacking a city that held such a hallowed place in Japanese consciousness would prove counterproductive, stiffening resistance and hardening anti-American sentiments. Against strenuous opposition, he won his case for removing Kyoto from the target list in late July by taking it directly to President Truman.59

The United States successfully tested the world’s first nuclear weapon in the desert in Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16. Truman received the news in Potsdam, Germany, where he was meeting with the leaders of England and the Soviet Union to discuss the future of postwar Europe and conduct of the ongoing war against Japan. By the beginning of August, the U.S. military possessed two nuclear bombs based on the fission of two significantly different isotopes (uranium 235 and plutonium 239). The uranium bomb, nicknamed “Little Boy,” was dropped by parachute directly over Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. on August 6—coinciding with a time of day when many people were outdoors on their way to work or other morning activities, and timed to explode some 1,900 feet above ground so that the blast would wreak the most havoc. The thermal heat released at the hypocenter was between 5,400 to 7,200 degrees Fahrenheit (3,000 to 4,000 degrees Centigrade). Apart from tens of thousands of victims who were immediately incinerated, serious flash burns were experienced by unshielded individuals within a radius of 1.9 miles (3 kilometers), while lesser burns were incurred as far away as 2.8 miles (4.5 kilometers). The simultaneous eruption of fires all over the stricken area caused an inrush of “fire wind” that over the next few hours attained velocities of thirty to forty miles per hour, creating a firestorm comparable to that which devastated Tokyo in the March 9 incendiary raid.

Three days later, after heavy cloud cover forced Kokura to be abandoned as the target of the second bomb (nicknamed “Fat Man” because of its bulbous shape, and apparently also with the jocular innuendo of resembling England’s portly Prime Minister Churchill), Nagasaki was bombed. In this case, the bomb was dropped at 11:02 a.m. and fell approximately two miles northwest of the planned hypocenter. Fat Man exploded at an altitude of some 1,500 feet above a section of Nagasaki called Urakami, and the scope of the blast and ensuing conflagration were confined by surrounding hills. The fires were less intense than in Hiroshima, and the radius of utter destruction was smaller. It is possible, at least for those so inclined, to see a certain symbolism in the fact that the Nagasaki bomb exploded close to the imposing Catholic cathedral in Urakami, and the Hiroshima bomb directly above a large hospital.60

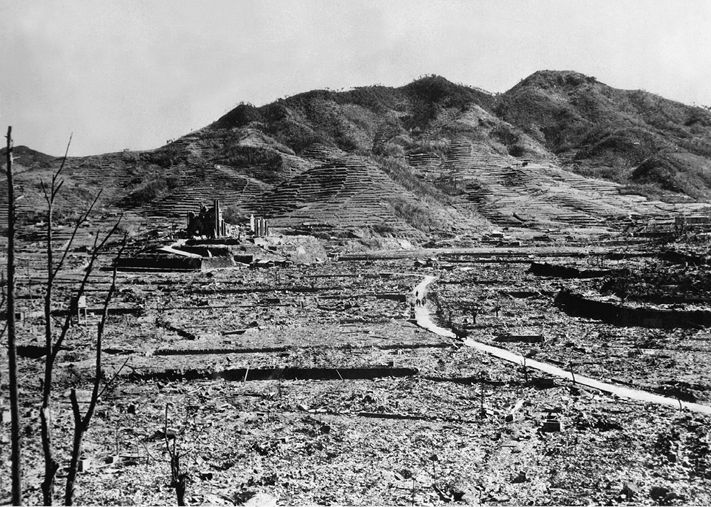

Early postwar estimates of the damage inflicted by the two nuclear weapons were accurate when it came to the extent of devastation in the “zero area” of each target: approximately 4.4 square miles in Hiroshima and 1.8 square miles in Nagasaki were obliterated. Fatalities, however, were greatly understated. Relying on data provided by the Japanese, the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey reported in June 1946 that it “believes the dead at Hiroshima to have been between 70,000 and 80,000, with an equal number injured; at Nagasaki over 35,000 dead and somewhat more than that injured seems the most plausible estimate.” These early calculations, recycled in innumerable subsequent publications, lie behind the persistent but misleading argument that the first incendiary air raid on Tokyo killed more people than the atomic bombs. More recent and generally accepted estimates put the probable number of fatalities at around 130,000 to 140,000 in Hiroshima and 75,000 in Nagasaki, with most deaths occurring by the end of 1945. Some generally responsible (but less persuasive) sources place the total number of deaths from the two bombs as high as 250,000 in Hiroshima and 140,000 in Nagasaki. These latter exceptionally high fatality estimates amount to roughly 50 percent of the populations in the two cities.61

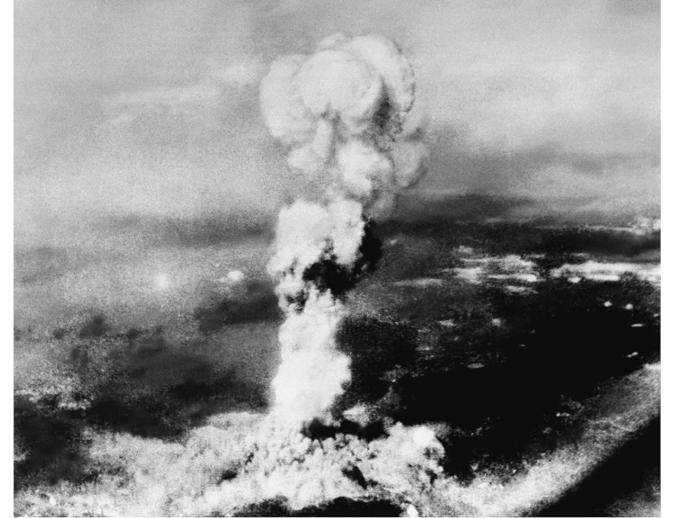

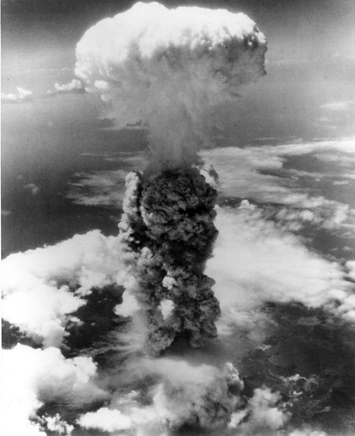

GROUND ZEROES, AUGUST 1945

The Hiroshima bomb, dropped on August 6, probably killed around 140,000 people. The death toll from the Nagasaki bomb three days later—which exploded some distance off target over the Catholic cathedral in the Urakami district—was around 75,000.

57. The mushroom cloud over Hiroshima.

58. Crossroad in the Hiroshima wasteland.

59. The mushroom cloud over Nagasaki.

60. The nuclear wasteland near the Urakami Cathedral in Nagasaki.

We will never know for certain how many men, women, and children were killed. Given the turmoil of the times, with people evacuating cities and troops moving into or passing through them, the population actually resident in the two targets in early August is unclear. Entire neighborhoods and residential areas were totally destroyed, including the paper records that might enable survivors to reconstruct who might once have lived there. To prevent spread of disease, corpses had to be disposed of quickly. Some survivors cremated their dead spouses, children, neighbors, and co-workers on their own; schoolchildren gathered a few days after the explosions to see dead classmates consumed in this eerie rekindling of fires; massive pyres of unidentified victims were hastily constructed and set aflame. Years later, some survivors remained haunted by the sight of this second round of deliberate fires, where in Hiroshima in particular the devastated nighttime landscape seen from a distance was pinpricked with the orange-red glow of cremations everywhere. Afterwards, people continued to die without necessarily being identified as bomb victims. For some survivors, and some kin of those who perished, to have been singled out for such a horrendous fate was a stigma to be concealed.

Most fatalities were caused by flash burns from the nuclear explosions, “secondary blast effects” including falling debris, and burns suffered in the ensuing fires. In the clinical language of the Strategic Bombing Survey, “many of these people undoubtedly died several times over, theoretically, since each was subjected to several injuries, any one of which would have been fatal.” The majority of deaths occurred immediately or within a few hours, but many victims lingered in agony for days, weeks, and months before perishing. There was virtually no medical care or even ointments, medicines, or painkillers initially (most doctors and nurses had been killed, and most medical facilities destroyed), and woefully inadequate care in the prolonged aftermath of the bombings. Deaths from atomic bomb–related injuries and diseases continued to occur over the course of ensuing years and even decades.

Apart from flash burns, the most unique cause of death came from exposure to gamma rays emitted by the fission process. Among survivors of the initial blast who had been near the centers of the explosions, the onset of radiation sickness usually occurred within two or three days. Individuals who had been exposed at greater distances, and who often initially appeared to have survived unscathed, did not show severe symptoms until one to four weeks later. In addition to fever, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting blood, discharging blood from the bowels, and bloody urine, these symptoms included (in the Strategic Bombing Survey’s summation) “loss of hair, inflammation and gangrene of the gums, inflammation of the mouth and pharynx, ulceration of the lower gastro-intestinal tract, small livid spots . . . resulting from escape of blood into the tissues of the skin or mucous membrane, and larger hemorrhages of gums, nose, and skin.” Autopsies “showed remarkable changes in the blood picture—almost complete absence of white blood cells, and deterioration of bone marrow. Mucous membranes of the throat, lungs, stomach, and the intestines showed acute inflammation.”

Years afterwards, a man who survived the Hiroshima bombing drew a picture of the pillowed face of his younger brother on his death bed, dying from the mysterious plague that was only identified as radiation sickness much later. Blood spilled from his nose and mouth, and a bowl filled with blood lay by the pillow. Text written on the picture explained that the brother had been demolishing buildings for firebreaks when the bomb was dropped, and was then recruited to help respond to the catastrophe. “He returned home on August 20, walking and apparently healthy, but around August 25 his nose began bleeding, his hair started falling out, small red spots appeared all over his body. On August 31 he died while vomiting blood.” Many thousands of other survivors could have drawn similar family portraits.62

In the Strategic Bombing Survey’s 1946 estimate, “no less than 15 to 20 percent of the deaths were from radiation,” a calculation that later sources tend to endorse. At the same time, the American researchers also speculated that “if the effects of blast and fire had been entirely absent from the bombing, the number of deaths among people within a radius of one-half mile from ground zero would have been almost as great as the actual figures and the deaths among those within 1 mile would have been only slightly less. The principal difference would have been in the time of the deaths. Instead of being killed outright as were most of these victims, they would have survived for a few days or even 3 or 4 weeks, only to die eventually of radiation sickness.”

The effects of residual radiation are difficult to evaluate, but it is possible that some individuals who entered the stricken cities within a hundred hours after the bombings were exposed to this. Although the weather was clear in Hiroshima and overcast in Nagasaki when the bombs were dropped, the explosions altered the atmosphere, causing moisture that condensed on the rising ash and dust to return as radioactive “black rain” in both cities. In the years that followed, the so-called late effects of radiation poisoning and other atomic bomb–related injuries took the form of statistically abnormal incidences of cataracts, blood cancers such as leukemia and multiple myeloma, and malignant tumors including thyroid cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, stomach cancer, salivary gland cancer, and malignant lymphoma. Burn victims often found their wounds healing in the form of particularly unsightly protuberant scars known as keloids.

Radiation, compounded by other atomic-bomb effects, also affected reproduction among survivors. Shortly after the bombings, sperm counts among males within 5,000 feet of the epicenter of the Hiroshima explosion showed severe reduction. More starkly visible was the harm to pregnant women and their unborn. The Survey summarized this as follows:

Of women in various stages of pregnancy who were within 3,000 feet of ground zero, all known cases have had miscarriages. Even up to 6,500 feet they have had miscarriages or premature infants who died shortly after birth. In the group between 6,500 and 10,000 feet, about one-third have given birth to apparently normal children. Two months after the explosion, the city’s total incidence of miscarriages, abortions, and premature births was 27 percent as compared to a normal rate of 6 percent.

Scores of women who had been in the first eighteen weeks of pregnancy when exposed to the radioactive thermal blasts gave birth to congenitally malformed offspring. Microcephaly, a condition characterized by abnormally small head size and sometimes accompanied by mental retardation, was observed in some sixty children who had been in utero at the time of the bombings. In later years, as these infants grew into adolescents and adults, they became one of many sad symbols of the enduring legacy of the bombs.63

Until more than a decade had passed, the general public in as well as outside Japan rarely asked or cared to see or hear what it was like to be permanently maimed, scarred, or otherwise disfigured; or to live wondering if one’s blood had been poisoned by radiation or, where such poisoning was assumed, if this would be passed on to children and generations yet unborn. The psychological trauma and social stigma of victimization by the atomic bombs—sometimes referred to in the newborn Japanese lexicon of nuclear affliction as “leukemia of the spirit” and “keloids of the heart”—were unquantifiable. Many survivors suffered lasting guilt that they had lived while so many around them, including loved ones, perished without their being able to help them. For many, life after August 1945 entailed what the psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton later characterized as a “permanent encounter with death.”64

Described in this clinical manner, the human effects of the atomic bombs seem almost preternaturally malevolent. They could have been imagined beforehand; and, in certain almost strangely detached ways, they were. The 509th Composite Group that was established in September 1944 to train the air crews selected for the nuclear mission, for example, focused on precision bombing from an exceptionally high altitude (as high as 30,000 feet, or between five to six miles); according to one account, “dropped a hundred and fifty-five Little Boy and Fat Man [non-nuclear] test units in the desert”; and devoted countless hours to perfecting banking sharply after release of a bomb to ensure not being taken down by the anticipated atomic blast. The projected danger area was within five miles of the explosion, and the targeted “distance-away” for the B-29 was double this.

As early as mid-May, two months before the new bomb was ready for testing, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific director of the “Manhattan Project” that secretly developed the weapon under Army auspices, addressed the unique peril to the bombing crew from a different direction. The minutes of his presentation to military planners “on the radiological effects of the gadget” summarized its basic recommendations as follows: “(1) for radiological reasons no aircraft should be closer than 2½ miles to the point of detonation (for blast reasons the distance should be greater) and (2) aircraft must avoid the cloud of radio-active materials.” (“Gadget” was the widely used code word for the prototype bomb.) On a later occasion, Oppenheimer informed the Interim Committee that radioactivity in all likelihood “would be dangerous to . . . a radius of at least two-thirds of a mile.”65

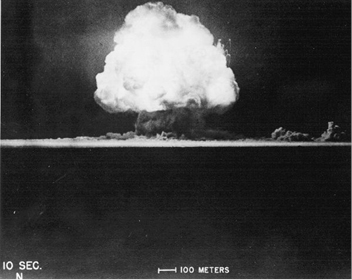

61. The Trinity fireball at .025 second.

TRINITY

62. The fireball at .090 second.

These scrupulous precautions concerning the safety of the bombers themselves extended to the mid-July Trinity test in the desert of New Mexico, where around 150 military officers and scientists viewed the explosion from slit trenches three feet deep, seven feet wide, and twenty-five feet long at a “base camp” located nine miles from Zero. The closest observation points, including the control center, were some 10,000 yards (5.7 miles) from where the bomb was sited on a hundred-foot steel tower, and involved shelters reinforced with cement and buried under thick layers of earth. Even observers positioned as far as twenty miles away were instructed that when a siren signaled “two minutes to zero,” they were to “lie prone on the ground immediately, the face and eyes directed toward the ground and with the head away from Zero.” They were given dark welder’s glass through which to view the spectacle following the blinding initial flash, and told to remain prone for two minutes to avoid harm from flying debris. They also were instructed to make sure car windows were open to avoid being shattered by the blast.

Every living creature within a radius of a mile from the Trinity hypocenter—every reptile, animal, and insect—was exterminated, and the dazzling light from the explosion in the night sky was powerful enough to cause temporary blindness. (When the crews selected to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki were briefed about their actual mission for the first time on Tinian island, they were given special polarized goggles and the alarming warning—as one airman recorded—that “a soldier stationed twenty miles away sitting in a tent was blinded by the flash” during the test of the bomb.) The elite cadre of American, British, and European émigré scientists who planned and carried out the development and use of the bombs, and ushered in a new age of mass destruction in the process, thus did so with eyes protected but wide open—except when it came to imagining precisely whom they were killing, and how casually, and how great the slaughter would actually be. On the latter score, Oppenheimer ventured the modest guess of perhaps twenty thousand Japanese fatalities from one bomb.66

63. Mushroom cloud forming at 2 seconds.

64. The mushroom cloud at 10 seconds.

At the same time, however, American and British leaders, including the scientists, immediately recognized the new weapon’s potential for world-transforming catastrophe. Before Hiroshima and Nagasaki confirmed that a single bomb could now destroy an entire city as thoroughly as the earlier raids against Germany and Japan, which had required hundreds of planes carrying huge bomb loads; before anyone saw aerial photographs of the obliterated “zero areas” of the two pulverized Japanese cities, let alone beheld the destruction firsthand; before the Strategic Bombing Survey produced its influential report on “the effects of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki”; before the technicians produced a “Standardized Casualty Rate” calculation that Little Boy had been 6,500 times more efficient than an ordinary high-explosive bomb in producing death and injury—before any of this, the language of Apocalypse had already been introduced to war talk.67

In an eyewitness report on the July 16 test, for example, Brigadier General Thomas Farrell immediately turned to thoughts of divinity, transgression, and doom. “The strong, sustained, awesome roar,” he wrote, “warned of doomsday and made us feel that we puny things were blasphemous to dare tamper with the forces hitherto reserved to The Almighty.” The Harvard chemist and explosives expert George Kistiakowsky found himself haunted by the same image, describing the Trinity spectacle as “the nearest thing to Doomsday that one could possibly imagine.” “I am sure,” the only journalist at the test recorded Kistiakowsky saying, “that at the end of the world—in the last milli-second of the earth’s existence—the last man will see what we saw!” When news of the successful test reached Potsdam, Churchill characterized the new weapon as “the Second Coming—in wrath.” Truman similarly turned to biblical prophecy to express his thoughts. In a handwritten diary scribbled on loose sheets of paper at Potsdam, the president wrote, on July 25, that “we have discovered the most terrible bomb in the history of the world. It may be the fire destruction prophesied in the Euphrates Valley Era, after Noah and his fabulous Ark.”68

Oppenheimer too summoned ancient doomsday theology, in this case the Hindu tradition, to find adequate expression for what he and his colleagues felt when they opened the door to an unprecedented capacity for mass slaughter. “We knew the world would not be the same,” he famously recalled when asked to describe what it felt like to harness the destructive forces of the atom. “A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty, and to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”69

Despite such visions of Apocalypse, the policy makers, scientists, and military officers who had committed themselves to becoming death managed to dress and soften their doomsday visions with garments of euphemism and cocoons of comforting denial. They never seriously considered not using their devastating new weapon. They did not talk about turning mothers into cinders or irradiating even the unborn. They brushed aside discussion of alternative targets, despite the urging of many lower-echelon scientists that they consider this. They gave little if any serious consideration to whether there should be ample pause after using the first nuclear weapon to give Japan’s frazzled leaders time to respond before a second bomb was dropped. Rather, the theoretical scientists, weapon designers, bomb builders, and war planners adopted the comfortable, dissembling language of destroying military targets that already had been polished to high gloss in the saturation bombing campaign that devastated sixty-four cities prior to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The Interim Committee had established the criteria for being selected as a prospective atomic-bomb target by the end of April. Although this preceded LeMay’s initiation of the incendiary bombing of “secondary” Japanese cities by several months, the priorities for determining desirable nuclear targets were much the same. As recapitulated by General Leslie Groves, the key military coordinator of the Manhattan Project, the “governing factor” in choosing targets was that they “should be places the bombing of which would most adversely affect the will of the Japanese people to continue the war.” Military considerations in the form of command posts, troop concentrations, or war-related industry were secondary to this. Overarching this were the practical provisos of any thoroughgoing experiment: that the target city should have escaped prior bombing and “be of such size that the damage would be confined within it, so that we could more definitely determine the power of the bomb.”70

Secretary of War Stimson, one of Truman’s major links to the military planners and a man widely admired for seriously engaging moral issues, provides an excellent example of this peculiar exercise in evasive ratiocination. On May 31, he recorded that the Interim Committee had reached the decision “that we could not give the Japanese any warning; that we could not concentrate on a civilian area; but that we should seek to make a profound psychological impression on as many of the inhabitants as possible.” Stimson agreed with the suggestion of James Conant, another Interim Committee member and since 1933 the president of Harvard, “that the most desirable target would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ houses.” Boston Brahmins and ivory-tower intellectuals—and every other statesman at the Interim Committee’s planning table—apparently saw no contradiction between targeting a crowded blue-collar residential area with the most deadly weapon ever made and claiming to “not concentrate on a civilian area.”71

It was through such rhetorical gymnastics—through what Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin nicely call “such delicate euphemisms,” and Gerard DeGroot characterizes as “window dressing to assuage the guilt of those who found terror bombing unpalatable”—that the decision was made to obliterate two densely populated cities while denying that this meant deliberately targeting civilians. Stimson’s diary entries and casual observations to others are as tortuous on this score as his more formal public utterances, and the fantasizing he engaged in while planning the destruction of worlds obviously rubbed off on his commander in chief. In the same “Potsdam diary” entry for July 25 in which Truman wrote of possessing “the most terrible bomb in the history of the world,” the president also wrote this:

This weapon is to be used against Japan between now and August 10th. I have told the Sec. of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop this terrible bomb on the old capital or the new [that is, on Kyoto or Tokyo].

He and I are in accord. The target will be a purely military one and we will issue a warning statement asking the Japs to surrender and save lives. I’m sure they will not do that, but we will have given them the chance. It is certainly a good thing for the world that Hitler’s crowd or Stalin’s did not discover this atomic bomb. It seems to be the most terrible thing ever discovered, but it can be made the most useful.72

In the Potsdam Declaration of July 26, the United States, United Kingdom, and China called on the Japanese government to submit to terms amounting to unconditional surrender or face “prompt and utter destruction.” This was the extent of the “warning statement,” and its vagueness amounted in practice to the Interim Committee’s no-warning decision of May 31. More striking, however, is the president’s characterization of the nuclear targets as “purely military” and excluding women and children. In a radio broadcast following the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Truman persisted in describing the target as “a military base . . . because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians,” and in his memoirs he characterized Hiroshima similarly as a “war production center of prime military importance.”

What the diary suggests—along with the table talk of the bomb planners more generally—is that this mythmaking was more than willful misrepresentation. It is better understood in terms of the self-deception, psychological avoidance, and moral evasion that almost necessarily accompanied the so-called strategic air war in general. (Truman’s “Potsdam diary” was a spontaneous record of the president’s daily thoughts, and for decades remained buried among the papers of a minor functionary at the Potsdam conference and unknown to researchers.) Faith in one’s own and one’s nation’s righteous cause, and to some degree personal sanity itself, required closing off any genuinely unblinking and sustained imagination of what modern warfare had come to.73

Like all large Japanese cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were undeniably involved in the military effort. In addition to war-related factories and the presence of troops, Hiroshima in particular was a major command center and point of departure for fighting men embarking for the continent and points south. By August 1945, however—with the Japanese navy and merchant marine at the bottom of the ocean, Okinawa in Allied hands, the nation cut off from outside resources, six major cities and fifty-eight “secondary” cities and towns already pulverized by incendiary bombing, and the Japanese leadership known to be groping for an exit strategy—it was meaningless to speak of these two targets as “military objectives” in any conventional sense. They were psychological-warfare targets—an entirely new level of terror “under other pretexts.”

As the Strategic Bombing Survey put it, “The two raids were all-Japan events and were intended so: The Allied Powers were trying to break the fighting spirit of the Japanese people and their leaders, not just of the residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Oppenheimer came to the same conclusion after the event, and put it in even stronger terms as he contemplated the world his contribution to the Manhattan Project had ushered in. “The pattern of the use of atomic weapons was set at Hiroshima,” he wrote less than four months after the war. “They are weapons of aggression, of surprise, and of terror. If they are ever used again it may well be by the thousands, or perhaps by the tens of thousands; their method of delivery may well be different, and may reflect new possibilities of interception, and the strategy of their use may well be different from what it was against an essentially defeated enemy. But it is a weapon for aggressors and the elements of surprise and terror are as intrinsic to it as are the fissionable nuclei.”74

In the years after his presidency ended, Truman often garnered praise bordering on adulation for his plain speaking and common sense. That such a pragmatic man, placed in the cauldron of war and at the very highest level of authority, could approve targeting densely populated cities on one day, and speak of his terrible new weapon as the fire destruction prophesied in the Old Testament on another, and still imagine “women and children” would be largely excluded from harm is testimony to the extent to which psychological warfare had become inseparable from psychological denial and delusion.

Ending the War and Saving American Lives

Denial and delusion went hand in hand with a clear, concrete concern that understandably dominates mainstream analysis of the decision to obliterate the two Japanese cities: to end the war quickly and save American lives. The analogue to this preoccupation after September 11 was equally compelling, albeit ironic. In August 1945, the professed goal was to save American lives by unleashing the most terrible weapons of mass destruction in the history of the world. The goal after 9-11 was to save American lives by preventing the ghastly spawn of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs from being unleashed by stateless or state-sponsored terrorists.

After Japan’s surrender, the question of how many American lives were saved by dropping the atomic bombs and precipitating Japan’s capitulation without having to invade the home islands became a fiercely contested subject. Truman spoke at one point in his memoirs of anticipating a half-million casualties and at another point a half-million deaths. (Deaths, nonfatal battle injuries of varying severity, and non-battle casualties like illness or psychological disability from combat stress were easily conflated or confused in wartime projections and, much more so, in postwar recollections.) In a public exchange at Columbia University many years later, he typically and defiantly asserted that he had no second thoughts about his decision to drop the atomic bombs, and offered an even larger projection of lives spared: “It was merely another weapon in the arsenal of righteousness,” he declared, and “saved millions of lives. . . . It was a purely military decision to end the war.”75 Churchill retrospectively suggested at one point that the atomic bombs saved 1.2 million Allied lives (1 million of them American), and justified using them with characteristic eloquence in the final volume of his acclaimed history of World War II: “To avert a vast, indefinite butchery, to bring the war to an end, to give peace to the world, to lay healing hands upon its tortured peoples by a manifestation of overwhelming power at the cost of a few explosions, seemed, after all our toils and perils, a miracle of deliverance.”76

Other participants in the decision to use the bombs similarly emphasized their overriding concern with the mounting human cost of the campaign against Japan and the heavy U.S. losses this portended in any projected invasion. No responsible military or civilian leader could possibly have thought otherwise. As Stimson, the always reflective (but not always consistent or forthcoming) former secretary of war put it in a widely discussed article published in Harper’s in 1947, “My chief purpose was to end the war in victory with the least possible cost in the lives of the men in the armies which I had helped to raise.”77 Former Army chief of staff George Marshall, another military leader admired for his moral integrity, similarly recalled the ferocity of Japan’s no-surrender policy as seen in Okinawa, and coupled this with the apparent resilience of Japanese morale even after the devastating Tokyo air raid and all the incendiary urban air attacks that followed this. “So it seemed quite necessary, if we could, to shock them into action” by using the atomic bombs, he recalled. “We had to end the war; we had to save American lives.”78

These were not rationalizations after the event, nor did they reflect a misreading of Japan’s fanatical no-surrender policies. It was the hope of Japan’s leaders that the suicidal defensive battles that began with Saipan in mid-1944 and extended to Iwo Jima and Okinawa would discourage the Allied powers from pursuing thoroughgoing victory and persuade them to negotiate some sort of compromise peace. Essentially, the warlords in Tokyo were still beguiled by the same sort of wishful thinking about the psychological weakness and irresolution of the American enemy that led them to attack Pearl Harbor in the first place. When Emperor Hirohito ignored advice to end the war in early 1945, he threw his support instead behind the advocates of an all-out defense of Okinawa, which it was hoped would convince the United States that Japan was willing to fight to the bitter end. (This vision of a decisive land battle calls to mind the earlier misguided faith of the Japanese “battleship admirals” that the enemy might be thoroughly demoralized and defeated through a single decisive battle at sea.) The basic plan for a final defense of the homeland, code-named Ketsu-Go (literally, Decisive Operation), was approved and disseminated to field commanders in early April. This called for suicidal resistance beginning with kamikaze attacks against the invading fleet, continuing with intense military resistance at the beachheads, and extending if and when necessary to the active self-sacrifice of all the emperor’s loyal adult subjects, women and men alike. It was reasonable to anticipate that “Okinawa” would have been replicated in mayhem many times over in any projected invasion, and the internal record on the U.S. side confirms how deeply this weighed on the minds of the war planners.79

65. This scene of three dead American soldiers on Buna Beach in Papua, New Guinea, marked a turning point in U.S. media coverage of the Pacific War when it appeared as a full-page picture in the September 20, 1943, issue of Life. The photograph, taken by George Strock seven months earlier, was initially withheld from release under the official U.S. policy of accentuating the positive and not showing graphic images of dead or gravely injured Americans. Publication of this and similar stark images marked the formal end of such censorship and the beginning of a rising crescendo of horror at the human costs of the war and rage at the Japanese responsible for this. Life devoted a long editorial to the Buna Beach photograph, describing the dead men as “three fragments of that life we call American life: three units of freedom.” To the end of the conflict, the faces, names, and unit insignia of photographed American corpses remained concealed. They became emblematic victims, symbols of the war’s terrible toll.

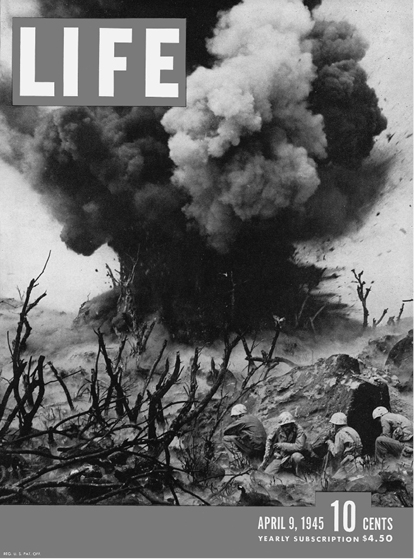

66. Life featured another iconic rendering of the war in the Pacific on the cover of its April 9, 1945, issue—here, a cropped version of W. Eugene Smith’s photograph of a marine demolition team destroying a Japanese blockhouse and fortified cave on “Hill 382” on Iwo Jima. Hill 382, nicknamed “Meat Grinder,” was overrun only after five previous attempts had failed. Iwo Jima “conveyed a sullen sense of evil to all the Americans who saw it for the first time,” Life told its readers, and “seemed like a beachhead on hell.” In its archive of “Great War Photos,” the magazine described this as “one of the most starkly violent cover photos in LIFE’s long history,” and the lengthy cover story itself also included a full-page picture by Smith of a cemetery of white crosses, representing a fraction of the more than 6,800 U.S. fighting men who were killed taking the island. This was the atmosphere in which the U.S. Army Air Forces carried out their campaign of systematically firebombing Japanese cities.

Casualty projections were at best reasoned guesses, and U.S. planning for an invasion of the home islands not only was subject to constant reevaluation but also was a generally compartmentalized procedure, involving many branches and subunits of the military. There was, however, one rough calculation that seems to have generally influenced military thinking from the fall of Saipan in early July 1944 through the spring of 1945. Known as the “Saipan ratio,” this was formulated as follows in a Joint Chiefs of Staff planning document dated August 30, 1944: “In our Saipan operation, it cost approximately one American killed and several wounded to exterminate seven Japanese soldiers. On this basis it might cost us half a million American lives and many times that number wounded . . . in the home islands.” Right up to the dropping of the bombs, most formal military plans anticipated that the conflict, including a projected two-stage invasion, would continue well into 1946.80

Inevitably, these estimates fluctuated over time. U.S. intelligence did not have access to Ketsu-Go, but it did not require code breaking to decipher the thrust of enemy thinking. Japan’s suicidal policies—including the callous sacrifice of civilian populations as well as fighting men on its own side (shockingly displayed on Saipan in mid-1944 and Okinawa in the spring of 1945) and desperate deployment of kamikaze (beginning in October 1944)—meshed with other considerations to heighten U.S. visions of how costly an invasion would be. Knowledge that Japan had reserved army forces several-million strong to defend the home islands was one such consideration. Japanese edicts in the spring of 1945 mobilizing all adult men and women into a ragtag but nonetheless alarming homeland defense force reinforced the prospect of truly tenacious resistance, accompanied as it was by increasingly hysterical rhetoric exhorting the “hundred million” to die gloriously in defense of the nation and its emperor-centered “national polity.” The high human costs of the Allied endgame against Germany also influenced U.S. planners, who among other considerations were well aware that Soviet forces had taken the brunt of these casualties, whereas any invasion of Japan would fall almost entirely on U.S. forces. It was with the war against Japan in mind that the U.S. Selective Service upped its monthly draft quotas in early 1945.81

This was the atmosphere in which, in May 1945, former president Herbert Hoover submitted an alarming estimate of projected casualties to Stimson and Truman, suggesting that if peace could be arranged with Japan, “America will save 500,000 to 1,000,000 lives” (which would extrapolate to a total number of casualties of between two and four million). On June 4, the War Department, with General Marshall concurring, dismissed these estimates as “entirely too high.” General MacArthur, who would have commanded the projected invasion, also projected confusing but drastically lower casualty estimates for the first ninety days. By mid-June, the “Saipan ratio” had been supplanted by other models (such as casualties in the Leyte and Luzon campaigns, as well as Iwo Jima and Okinawa), and projections of initial American fatalities lowered to the tens of thousands. Still, the dire grand figures retained their mesmerizing, almost emblematic attraction. After the war, General Dwight D. Eisenhower recalled meeting with Stimson during a break in the Potsdam Conference in late July 1945 and finding the secretary of war “still under the influence of a statement from military sources who figured it would cost 1,000,000 men to invade Japan successfully.”82

While military planners reworked their projections of invasion fatalities and revised them downwards, in some cases to as little as a tenth or twentieth of what the alarmists were predicting, what remained unchanged was the overriding vision of unacceptable potential losses. The “1.2 million,” “million,” “half million” numbers amounted to a kind of numerological shorthand for “huge”—rather like the exaggerated evocation of the “hundred million” that the Japanese used when referring to the emperor’s loyal subjects, and not entirely different from wildly inflated references to “one-million” and possibly “two-million” fatalities in bombed-out Tokyo that the New York Times so casually reported on May 30, 1945, based on what the military was telling it. The fundamental difference, of course, was that American lives were precious.83

Whatever the number might be, it was to be avoided at all costs. On June 16, for example, the top-level “Science Panel” that advised the Interim Committee endorsed immediate use of nuclear weapons on the grounds that “we recognize our obligation to our nation to use the weapons to help save American lives in the Japanese war.”84 At a key meeting at the White House two days later—on June 18, three days before it was announced that the fighting on Okinawa had finally come to an end—General Marshall expressed the common view that an invasion “would be much more difficult than it had been in Germany.” Truman took the occasion to state his hope “that there was a possibility of preventing an Okinawa from one end of Japan to the other.”85 At the Trinity test one month later, General Farrell’s first words to General Groves were, “The war is over,” to which Groves recalled replying, “Yes, after we drop two bombs on Japan.” When Colonel Paul Tibbets, the pilot of the Enola Gay, the B-29 that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, briefed his crew prior to takeoff, he spoke of the honor of being chosen to conduct the raid and predicted it might shorten the war by six months or more. “And you got the feeling,” one of his crew recorded in his diary, “that he really thought this bomb would end the war, period.”86

KAMIKAZE

67. Six kamikaze pilots pose for a group portrait before departing on their missions.

68. A kamikaze about to hit the USS Missouri off Okinawa, April 11, 1945. Less than five months later, Japan’s formal surrender took place on the Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

69. A kamikaze bursts into flame upon hitting the USS Intrepid in the Philippines, November 25, 1944.

70. U.S. sailors killed in a kamikaze attack on the USS Hancock are buried at sea off Okinawa, April 9, 1945.

In a report on the Potsdam Conference broadcast on August 9, Truman concluded with reference to “the tragic significance of the atomic bomb” dropped on Hiroshima and eschewed the exaggerated slaughterhouse projections that later came to dominate postwar rationalizations, including his own, for using it. He stated that the bomb had been used “in order to shorten the agony of war, in order to save the lives of thousands and thousands of young Americans.” In a message to Congress on atomic energy on October 3, he spoke similarly about how the bomb had “saved the lives of untold thousands of American and Allied soldiers who would otherwise have been killed in battle.”87

Thousands and thousands. Untold thousands. This in itself was indicative rhetoric, synonymous with far-too-many. At the same time, it also was indicative of how far American war planners had traveled from moral considerations that preoccupied many of them only a few years earlier—when pre–Pearl Harbor statesmen like Franklin Roosevelt were still able to declare that “ruthless bombing from the air . . . which has resulted in the maiming and in the death of thousands of defenseless men, women, and children, has sickened the hearts of every civilized man and woman, and has profoundly shocked the conscience of humanity”; and when, in the earliest years of the ensuing air war, American advocates of precision bombing still spoke seriously about the moral imperative of avoiding, as much as possible, untold thousands of casualties among enemy noncombatants.

Those days were gone forever. With their passing, and in their stead, a model had been established for future exercises in psychological warfare, terror, reliance on deployment of maximum and virtually indiscriminate force, and the obsessive development of weapons of ever more massive destructive capability.