OCCUPIED JAPAN

AND OCCUPIED IRAQ

Winning the War, Losing the Peace

Shortly after Japan’s surrender, Shigeru Yoshida, who would eventually serve as prime minister for more than six years between 1946 and 1954, attempted to put an optimistic gloss on his country’s predicament. History provides examples of losing in war but winning the peace, he reminded his compatriots, and that is what the nation had to set its collective will to accomplishing. Years later, after Japan emerged as an economic power in the 1970s, many commentators concluded this had happened. The occupation of the defeated nation ended with a conservative government firmly in power. A capitalist phoenix rose from the ashes, staunchly allied with the United States. And the crusty Yoshida became, in retrospect, a minor prophet.1

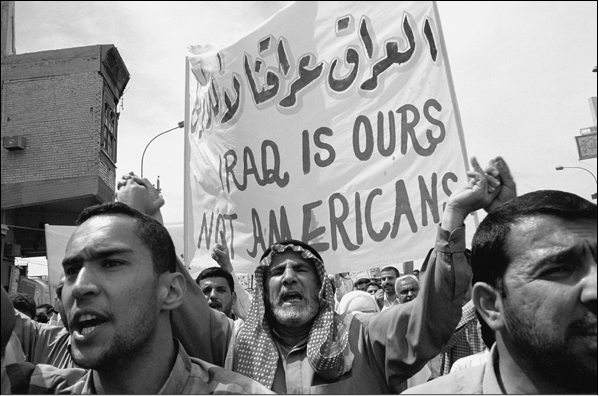

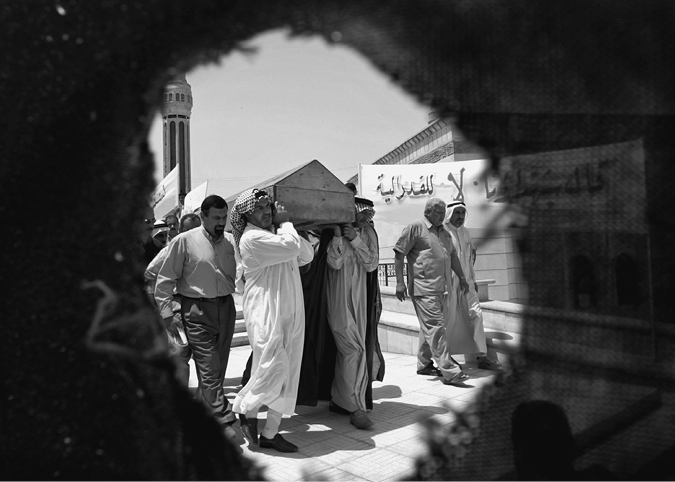

In the spring of 2007, close to the fourth anniversary of President Bush’s “Mission Accomplished” performance announcing that “major combat operations in Iraq have ended,” Ali Allawi, a longtime exile in London who returned to Iraq to hold several ministerial positions after the invasion, delivered a speech in the United States titled “The Occupation of Iraq: Winning the War, Losing the Peace.” He was promoting his insightful and mournful book of the same title. Iraq had long since plunged into chaos, the occupation had become one of the most disgraceful overseas failures in U.S. history, and mere mention of “victory” evoked sorrow, cynicism, and scorn. Iraq had become hell of a different kind than under Saddam Hussein, with no good exit in sight. No more striking contrast to the U.S.-Japan precedent of war and occupation could be imagined.2

There are few rhetorical old saws more timeworn than winning the war but losing the peace; and although precisely this warning was issued with some urgency in government circles in the months preceding the Iraq invasion, it was not taken seriously at top levels.3 Nor were the real lessons of post–World War II occupations taken seriously. Although few critics anticipated the quotidian incompetence of U.S. post-invasion planning and performance in Iraq, it was clear before war was launched that occupied Japan should have been a red light. To think otherwise—to evoke Japan as some sort of assurance that the United States could easily win the peace once it had been victorious in the combat phase of Operation Iraqi Freedom, and that “democracy” would follow fairly naturally in another land that was neither Western nor Christian nor largely Caucasian—was to engage in false analogy and magical thinking.

Beginning in the second week of October 2002—as a small piece in the propaganda campaign about weapons of mass destruction, “mushroom clouds,” and Saddam’s alleged support of Al Qaeda that mobilized American sentiment behind the impending war—the White House ventured to strengthen its case by floating the putative success stories of postwar Japan and Germany. From the outset Japan was the more attractive model of the two, since Germany had been divided into U.S., British, French, and Soviet zones of occupation and ended up in the Cold War partition known as West and East Germany. By contrast, although occupied Japan was nominally under the control of the victorious Allied powers, in practice the United States ran the show. Even years later, as violence continued to consume Iraq, the “postwar Japan” analogy remained cherished by the White House. When a surge in troop numbers was introduced to stave off outright defeat in the summer of 2007, for example, the president’s speechwriters still deemed it effective to cite defeated Japan as reason for maintaining hope in the emergence of a democratic Iraq.4

Where discrepancy between labels and realities is concerned, occupied Iraq followed the pattern established in Japan. “Coalition” replaced “Allied” as the nominal cover of the undertaking, while for all practical purposes the United States exercised unilateral authority. There were other points of similarity or partial congruity as well, many of them highly suggestive, as will be seen; but fundamentally the two occupations were as different as night and day. Both the victors and losers in World War II won the peace in Japan. In Iraq, there was no peace.5

Using defeated Japan to paint a positive picture of what to anticipate in Iraq was perverse, for the two nations differed enormously and so did the wars and occupations being addressed. Beyond this, the U.S. government in the opening years of the twenty-first century bore only shadow resemblance to that of 1945—not merely in ideological orientation (beneath a deceptive common rhetoric of “freedom and democracy”) but also in operational procedures. Even the most rudimentary checklist of why the occupation of Japan unfolded without violence and jump-started a functional postwar democracy provided a sobering reminder of what would not be present in any imaginable post-hostilities Iraq. Evocation of postwar Japan as a reassuring precedent was not simply a misreading of the past. It was bowdlerization: another example of wishful thinking compounded by delusory “cherry-picking”—in this case, ransacking not raw intelligence data but history itself.

Occupied Japan and the Eye of the Beholder

Defeated Japan did not regain sovereignty until April 1952, making the period of U.S. control almost three years longer than the Pacific War itself. The world order was tumultuous during this period, and by 1949 Asia had become a cauldron of Cold War tensions. The Soviet Union tested its first nuclear weapon that year; the Chinese Communists took Beijing and extended their control over the entire country; Southeast Asia was aflame with anticolonial revolutions (ignited by imperial Japan’s rout of the European powers). War erupted in Korea in June 1950. In this tumult, occupation policy in Japan passed through several stages, beginning with a radical agenda of “demilitarization and democratization” and ending in a “reverse-course” campaign to crush the political left, reconstruct a “self-sufficient” export-oriented economy, promote Japanese rearmament, ensure the indefinite retention of U.S. military bases on Japanese soil, detach Okinawa from the rest of Japan as a major strategic (and nuclear) garrison, and lock Japan economically and diplomatically as well as strategically into the “containment” of communism, particularly vis-à-vis China. (This last policy lasted until the Nixon-Kissinger rapprochement with China in 1972.) Seen whole, start to finish, the occupation reveals a certain schizophrenia.

Problems rooted in these years plagued Japan into the twenty-first century, when the occupation was being singled out as an encouraging beacon for Iraq. Okinawa remained a grotesquely militarized U.S. outpost. Electoral politics remained warped by a canny and corrupt conservative hegemony that traced back to a decisive electoral victory under Prime Minister Yoshida in early 1949 and was not seriously upended until 2009, after the Bush presidency ended. Economic growth was hindered by entrenched practices of government intervention that had roots in the war years and had been reinforced during the occupation. Ideologically, conservative and right-wing attempts to sanitize imperial Japan’s war crimes were stronger than ever a half century after the defeat, reflecting both festering resentment at the “victor’s justice” aspects of the postwar war-crimes trials conducted by the Allied powers and chagrin at still being constrained by a postwar constitution that prohibited Japan from dispatching military forces overseas—to Afghanistan and Iraq, for example—like a “normal” nation.6

From a Japanese perspective, there was an ironic, bitter twist to watching Americans invoke the “success” of occupied Japan to brighten the picture of what might be anticipated in postwar Iraq. While the Japanese government threw wholehearted support behind the Bush administration’s war policy (playing the role, as it were, of the England of Asia), Japan’s own experience of being occupied was regarded by many as a humiliating chapter in the nation’s history—more dishonorable even, some would have it, than the war years. Transcending or escaping “the postwar” was a mantra among Japanese conservatives—and “postwar” (sengo) was code for a litany of negative rather than positive legacies of the occupation era, during which the nation had no sovereignty and was ruled by foreigners. Military emasculation was one such regretted legacy; the one-sided “victor’s justice” judgments of the Tokyo trials another, particularly as regurgitated by liberals and leftists on the one hand and foreigners on the other; lingering suspicion of flag-waving and anthem-singing patriotism another (U.S. occupation authorities had banned both); being constrained in paying official homage to the several million “departed heroes” (eirei) of the Asia-Pacific War who were enshrined in Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine another; still having as the basic law of the land a constitution originally drafted in English yet another.7

Rose-colored invocations of occupied Japan by Americans gearing up for war with Iraq thus fell in place with the other uncomfortable Japan-related images that poured out in the wake of September 11: Pearl Harbor and “infamy”; kamikaze and terror bombing; Japan’s membership alongside Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in the original “Axis” of evil; Ground Zero as transplanted code for American rather than Japanese victimization; all-out war against an Islamist enemy as fanatical as the emperor’s soldiers and sailors had been; the Stars and Stripes triumphantly raised at Iwo Jima; and so on. In theory, evoking Japan’s “American interlude” and postwar rebirth as a democratic and prosperous nation was—certainly in the eyes of Americans—benign and complimentary. In practice, being occupied and dictated to by foreigners, no matter how far in the past, is a wound to pride. In Japan’s case, moreover, reopening this wound called attention to one of the more subtle but malignant legacies of the long-ago occupation—the nation’s lingering image as an American client state.

Despite postwar Japan’s hard-earned status as a major economic power, the unabated fixation of Japanese leaders on currying American goodwill cast a pall of psychological as well as structural dependency over the nation’s accomplishments. Unqualified support of the Iraq war became but the latest manifestation of this. For reasons of its own, postwar Germany escaped such obsequiousness—and the open criticism of the Bush administration’s rush to war with Iraq by German leaders only served to highlight this difference. Nor was dependency and subordination just a slur leveled by cynical foreigners. “Client state” was also a self-disparaging perception in the same conservative constituencies that called for a new nationalism transcending the Americanization of the occupation period—even while simultaneously remaining America’s most deferential supporters through the Cold War and into the so-called war on terror. A half century after the occupation ended in 1952, many Japanese were still wrestling with an identity crisis that traced back to these immediate postwar years. In this situation, casual references to the Japanese precedent in conjunction with invading and occupying Iraq were at best discomforting.8

None of these tangled considerations mattered in Washington, of course, when it came to plucking grand models from recent history. Postwar Japan was peaceful, prosperous, capitalist, and compliant; and advocates of war against Iraq understandably found this useful in embellishing the scenario of a swift overthrow of Saddam’s Baathist regime followed by smooth transition to a democratic nation friendly to the United States. Apparent parallels were, on the surface, quite striking. Imperial Japan had been authoritarian and militaristic, oppressive within its borders and atrocious outside them. Unlike Germany, Japan was a non-Western culture and power that denounced “the West” fiercely when animosity was at its peak, but at the same time—again superficially like Iraq—it also had enjoyed periods of amity and collaboration with the United States and European powers. Who could resist drawing encouraging lessons from Japan’s grand postwar transformation from authoritarianism and aggression to a civil and prosperous society that posed no threat to others—not to mention its role as a secure base for projecting U.S. military power in a strategically critical part of the world? Who could resist the argument—and as time passed this became a particular favorite of President Bush—that Japan was proof positive that “democracy” did not require a Western milieu to take root?

Attentive students of history could resist these arguments, for one, as well as even casual observers looking for insight rather than ammunition. Before the war of choice against Iraq was unleashed, critics pointed out that the occupation of Japan succeeded largely for reasons that were, or would be, almost entirely absent in Iraq.9

Conspicuous among these differences was the virtually uncontested moral legitimacy of the United States venturing to occupy a defeated Japan. Japan had initiated the war, and the emperor himself announced its beginning, announced its end, and gave his full consent to the formal terms of surrender. None of America’s allies questioned the dominant role of the United States in a nominally Allied occupation; even the Soviet Union went along, after initial sputtering. (Stalin regarded U.S. control in Japan as essentially a quid pro quo for Soviet control in Eastern Europe.) Japan’s savaged Asian neighbors and victims, led by China, were happy to see the humbled and ruined nation under America’s iron hand.

Led by their suddenly supremely pragmatic sovereign, the Japanese people themselves by and large also accepted the unconditional nature of the surrender, the legitimacy of the occupation, and the inevitability and even desirability of following the dictates of the victor, however emotionally painful surrender itself might be. In his radio address on August 15 (Japan time) announcing acceptance of the terms of surrender, Emperor Hirohito exhorted his subjects to follow his lead in “enduring the unendurable and bearing the unbearable, to pave the way for a grand peace for all generations to come.” Two days later, he issued a separate rescript to the armed forces praising their gallantry, grieving over their losses, mentioning the entry into the war by the Soviet Union (but not the atomic bombs) as a major reason for laying down arms, and concluding by linking compliance with his August 15 message to the highest form of patriotism. “We charge you, the members of the armed forces,” this August 17 message read, “to comply faithfully with Our intentions, to preserve strong solidarity, to be straightforward in your actions, to overcome every hardship, and to bear the unbearable in order to lay the foundations for the enduring life of Our nation.”10

On August 25—with occupation forces still a few days away from actually setting foot in Japan—yet another imperial message endorsed orders for all army and navy personnel to demobilize in similar terms: “Turn to civilian occupations as good and loyal subjects, and by enduring hardships and overcoming difficulties, exert your full energies in the task of postwar reconstruction.” Two days later the minister of war, who had faced and overcome resistance to the surrender orders by a few small groups of officers, issued a final appeal to the army that also turned capitulation into a demonstration of patriotism. “We must behave prudently, taking into consideration the future of the nation,” he declared. “Do not become excited and conceal or destroy arms which are to be surrendered. This is our opportunity to display the magnificence of our nation.” The emperor’s loyal subjects complied—and a great many of them went on to embrace the surrender and occupation as a liberation from death and a welcome opportunity to eliminate the forces and institutions that had driven them into their disastrous war.11

Given the criticism the Bush administration provoked as it deflected the war against Al Qaeda into plans to attack Iraq, it was obvious that occupying Iraq would find no comparable approbation in the world at large or within the United States or the invaded country itself. The speed, arrogance, and indifference with which Washington dissipated the global sympathy and support that followed September 11 is breathtaking in this regard. Failure to impose control and security following the fall of Baghdad in April 2003, coupled with revelation that Iraq did not possess the arsenals that had been offered as the major reason preemptive war was necessary, precipitated the ultimate shredding of U.S. credibility—but that most critical of intangibles, “legitimacy,” was absent from the start. Critics who raised this issue before the war agreed Saddam was a brutal dictator, but this did not suffice to give the so-called lesser evil of invading and occupying his country legitimacy.12

Also predictably lacking in any projected post-Saddam Iraq was an essential component in the operational efficiency of the occupation of Japan: the carryover of competent administrative machinery. Emperor Hirohito was the most prominent symbol of this institutional continuity and stability, and his disciplined military establishment was retained long enough to carry out an orderly demobilization before being disestablished. Truly essential to the transition from war to peace, however, was the fact that while the military disarmed and demobilized, governing structures remained intact and administrators and technocrats remained at their jobs top to bottom, from Tokyo to the remotest town and village. Even before widely criticized U.S. policies in Iraq such as dissolution of the military and the purge of top-level Baath Party members from public office were introduced, it was clear to critics that the Iraqi state—with its head decapitated and no obvious government capable of maintaining order—would not be remotely comparable to Japan once the dictator and his minions had been overthrown.

Further reason for pessimism in this regard was the impressive social cohesion that held Japan together during the difficult years required to win the peace. Political and ideological differences certainly existed in defeated Japan; early on, they found expression in the emergence of a militant but nonviolent labor and left-wing movement. To anyone who seriously placed the Japan of 1945 side by side with the Iraq targeted by America, however, this third realm of contrast seemed, again, simply enormous. No explosive schisms lurked just beneath the thick skin of the Japanese state. Religion posed no threat whatsoever in this polytheistic culture, apart from how it had been temporarily manipulated in the cause of a militaristic modern nationalism. There was, on the contrary, a compelling and carefully nurtured “Yamato race” history that traced back over a millennium to the earliest written chronicles of the eighth century. Twentieth-century ideologues had turned this sense of racial, cultural, and national solidarity in the direction of militarism and war, but postwar pragmatists like Yoshida could just as easily direct it toward peaceful reconstruction.

In Iraq, shared history was short. The Iraqi nation itself, after all, only dated back to British and French machinations in the wake of World War I. What ran perilously deep, on the other hand, were religious, ethnic, tribal, and regional fault lines. “Iraqi nationalism” was not a myth: the nation’s solidarity through eight years (1980–88) of ferocious war with Iran was proof of this. Such cohesion under Saddam’s police state was, at the same time, misleading. Like India at the time of partition in 1947, and Yugoslavia after Tito, and the Soviet Union in the wake of its fatal incursion into Afghanistan, absent force the center could not hold in Iraq.

The center did more than just hold in post-surrender Japan. It proved receptive to and capable of promoting much of the democratization agenda the Americans promoted in the first few years of occupation. This was possible because a resilient civil society had emerged prior to the rise of the militarists in the 1930s. This was a fourth realm of striking difference that advocates of the Iraq war chose to ignore. Japan’s Meiji Constitution of 1889 established a constitutional monarchy with an elective parliament that had remained in operation through the war years; party-led governments first appeared on the scene in 1918, and universal male suffrage was endorsed by the legislature in 1925. Starting around the turn of the century, and accelerating exponentially during the years Hirohito’s father occupied the throne (1912–26) and into the early 1930s, a variety of social and political developments took place that scholars weigh heavily (under the rubric “Taisho democracy”) in assessing the roots of Japan’s postwar pluralism. Electoral politics flourished; labor and women’s movements emerged; capitalist entrepreneurship took off after World War I; cosmopolitanism penetrated the ever more populous cities and towns that the B-29s would later incinerate; consumerism and “modernity” seeped into the countryside.

All this was fertile soil for the development of a more democratic Japan once the emperor’s holy war failed and the militarists were removed. Nor were the years of mobilization for “total war” that began in the 1930s and continued to 1945 necessarily retrogressive in this regard. Freedom was repressed, but creativity and social transformation flourished in ways that also bore positive legacies for postwar reconstruction. With sixty-six cities bombed, its Asian empire cut off at a stroke, and roughly one-quarter of the national wealth destroyed, Japan was to all outward appearances ruined when the fighting ended in August 1945. Until around 1948 or 1949, most urban dwellers struggled just to survive day to day. What mattered in the longer run, however, was that the human resources essential for reconstruction at both technological and technocratic levels were vastly greater at war’s end than they had been when the militarists gained control over a decade earlier.13

Iraq was a highly literate society that once possessed one of the most developed industrial economies in the Middle East. Many Iraqis, too, were skilled professionals who to one degree or another supported democratic ideals. Again, however, the Japanese case pointed more to deficiencies than similarities. No one could speak with heartfelt assurance of a truly promising experience with the values and practices of civil society prior to Saddam’s police state. The post–Gulf War decade of crippling economic sanctions against Iraq, moreover, compounded by the repression and ineptitude of Saddam’s corrupt rule, had undermined rather than accelerated enhancement of human resources. Much of the Iraqi leadership that war advocates counted on to lead “regime change” after Saddam was eliminated resided in a largely secular community of exiles and expatriates who had lived abroad for most of their adult lives and had no strong constituencies on their native soil. Civil society had been hollowed out in Iraq.14

A fifth seemingly obvious difference also failed to give pause to those who evoked postwar Japan as a heartening example: Japan’s isolation. This was both spatial and temporal. Japan was an archipelago with no porous contiguous borders. Until around 1947, moreover, no one in the larger world cared much about what was taking place there so long as it was not threatening. The nations and peoples of Japan’s short-lived empire—China, Korea, Southeast Asia—were consumed with their own conflicts. Europe and the Soviet Union were preoccupied with reconstruction, and where foreign policy was concerned they and the United States were fixated on nuclear issues and challenges in Eastern and Western Europe. There were no hostile outside forces or supra-state movements gathered around Japan viewing it as a potential prize—no counterparts, that is, to the Islamist fundamentalists and terrorists perched on Iraq’s borders.

Deprived of sovereignty, utterly lacking in critical natural resources, and dismissed for the moment as a fourth-rate power or worse, Japan in defeat was initially, apart from Okinawa, of slight strategic interest. The American reformers ensconced in Tokyo had the luxury of being able to introduce their reform agenda without much outside attention or intervention. Absent this cocoon of place and time, the occupation surely would have unfolded differently—as happened next door in the strategically contested Korean peninsula, for example, as well as in Okinawa. Both of the latter were subjected to militaristic U.S. policies from the outset, and neither has ever been evoked as a model of enlightened and successful occupation.

It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of this early breathing space. In all likelihood postwar Japan would have become democratic and pro-Western without the occupation, but in substance as well as form it would have become a different state with a different collective ethos. When the Cold War intruded and the United States turned against some of the more progressive reforms it originally sponsored, the old-guard conservatives led by Yoshida naturally were pleased. This, after all, was what the old man himself had in mind when he spoke early on about winning the peace. His satisfaction, however, was not unalloyed. Many fait accompli (like land reform, constitutional revision, thoroughgoing demilitarization, and promotion of progressive educational ideals) could not be undone easily. As Yoshida himself later ruefully put it, “There was this idea at the back of my mind that, whatever needed to be revised after we regained our independence could be revised then. But once a thing has been decided on, it is not so easy to have it altered.” The initial reforms may have been ordered by the Americans, but they quickly found a Japanese constituency.15

Landlocked Iraq was not merely the opposite of an island but also, by the Bush administration’s own choice, the bull’s-eye of world attention—central to U.S. strategy for controlling the Middle East and its natural resources, and central to what the present would portend politically for the future (liberalization and U.S. hegemony in theory, violence and accelerated instability in practice). There was neither physical security nor time to spare. At the topmost level where policy was actually formulated, however—or not formulated, as it turned out—very little of this registered.

Japan’s capitulation in the summer of 1945 caught most planners in Washington by surprise. Only a handful of policy makers were aware of the top-secret development of nuclear weapons, and the prevailing assumption was that the war would drag on deep into 1946. Despite this, the transition from war to peace in Japan proceeded smoothly—more so than in Germany and occupied areas of Europe, where national and ethnic rivalries were intense and atrocities were perpetuated on all sides, including by the victorious Allied forces; more so than in China and Southeast Asia, where war carried on in new forms; and vastly more so than in Iraq over a half century later.16

In the refracted darkness of occupied Iraq, it became clearer just how competent the planners who dealt with defeated Japan had been. They initiated serious planning for the war’s aftermath shortly after Pearl Harbor. They articulated U.S. and Allied intentions and objectives for the occupation quickly and clearly, announcing the terms of surrender before the atomic bombs were dropped and outlining the broad agenda of projected reforms within six weeks of the formal surrender on September 2. And they displayed a mature and generally pragmatic and bipartisan ability to bring a range of individuals, agencies, and political outlooks together in constructive ways from 1942 until 1947 or so, when domestic politics and Cold War fixations subjected Japan policy to an ideological litmus test. Throughout the entire period of occupation, moreover, the notion of social engineering—what would later be called nation building—was taken as a given. The state had an important role to play in civil affairs, tailored to the particular circumstances of time and place, and where Japan was concerned this applied to both the occupying power and the nation that was being occupied.17

Almost all of these seemingly straightforward assumptions and procedures became more noteworthy when set against what transpired in Iraq: the necessity of serious prior planning for the period after combat ended, the importance of articulating basic postwar objectives clearly and quickly, the benefits to be derived from engaging diverse opinions and encouraging genuine interagency collaboration, and the recognition that the state had a legitimate and essential role to play in realms beyond making or preventing war. What Iraq revealed was that these were not attitudes or procedures that could be taken for granted. To one degree or another, they were in fact repudiated in the run-up to invading Iraq.

From 1942 until 1947, much of the planning for postwar Japan was conducted under the aegis of “SWNCC,” an acronym for the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee. War and Navy were melded into the newly established Department of Defense in 1947, and thereafter grand policy affecting Japan carried the imprimatur of the also new National Security Council. General MacArthur’s orders were channeled through the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which amplified them, and it was the documents he received from the Joint Chiefs that he took as definitive.

82. August 19, 1945: One of two specially marked Mitsubishi “Bettys” touches down in Ie Shima in the Ryukyu Islands en route to Manila, where the logistics of Japan’s surrender and occupation were worked out at General MacArthur’s headquarters.

83. August 30, 1945: MacArthur—unarmed, dressed in casual summer dress, and smoking his trademark corncob pipe—arrives at Japan’s Atsugi airfield to assume control of the occupation as Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers.

OCCUPIED JAPAN

AND THE TRANSITION TO PEACE

84. September 29, 1945: A sensation at the time and the most famous occupation-era photograph ever since, MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito pose side by side at their cordial, historic first meeting. This single image captured the emperor’s descent from his erstwhile “sacred and inviolable” eminence and MacArthur’s dominance, while at the same time conveying the continuity of Japanese authority and governance that expedited a smooth transition to peace.

These were dense and reasonably orderly procedures, and before World War II ended, SWNCC had mobilized a great deal of expertise to assemble what was known about Japan and could be expected and accomplished once it was defeated. Interagency collaboration and division of labor were substantial rather than just nominal, with agencies such as the Office of Strategic Services, Office of War Information, and Foreign Economic Administration contributing to the process. Beginning in the fall of 1944, for example, the Research and Analysis Branch of the Office of Strategic Services coordinated the compilation of twenty-five informational “handbooks” about Japan on subjects ranging from government and administration to money and banking to cultural institutions. Between the summer of 1944 and summer of 1945, the Civil Affairs Division of the War Department assumed responsibility for an even more extensive series of “civil affairs guides” aimed at problems likely to be encountered in post-hostilities Japan. Some forty guides (of a projected seventy monographs) had been completed when Japan surrendered, and three in particular are regarded as having an impact on subsequent policy regarding labor, land reform, and local government. “Military government” training schools for both Germany and Japan were introduced under army and navy auspices in various locales in the United States beginning in 1942, and “civil affairs training schools” were established at Harvard, Yale, Chicago, Stanford, Michigan, and Northwestern in the summer of 1944.18

Many of the pre-surrender handbooks and guides did not have great impact, and many of the more than a thousand army and navy personnel who received intensive training in Japanese language, culture, and civil affairs were poorly used after the surrender, or not even deployed to Japan at all. What mattered more was that major branches of the government were seriously engaged in the process. They agreed on MacArthur’s appointment as supreme commander, which was formalized a few days before Japan’s mid-August capitulation. More significantly, despite the abruptness of Japan’s defeat, the state, war, and navy departments were in a position to put together a solid blueprint titled “United States Initial Post-Surrender Policy for Japan.” This was radioed to MacArthur on August 29, the day before he set foot in Japan. Most of the military officers and civilian officials who staffed the occupation’s general headquarters in Tokyo or were assigned to local duties were hastily recruited after the capitulation. At its peak, the staff at General Headquarters numbered around five thousand.

Japanese officials learned what surrender would entail beyond disarmament and demobilization in a series of statements that began with the Potsdam Declaration of July 26, which laid down the terms of surrender under the names of the United States, United Kingdom, and China. The “Byrnes Note” of August 11 concerning the future status of the emperor was the first of these statements—ambiguous enough to hold out promise that the throne would be respected, while at the same time unequivocal in affirming (as previously noted) that the authority of the emperor and Japanese government “shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers who will take such steps as he deems proper to effectuate the surrender terms.” How long would this take? It was impossible to say. On August 19 and 20, a high-level Japanese military team dispatched to Manila was given instructions by MacArthur’s command about disarming the imperial forces and preparing the homeland for arrival of the massive land, sea, and air forces of the victorious Allied powers.19

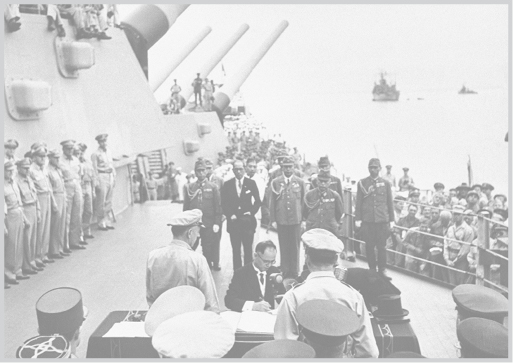

85. A casually attired GI distributing candy from his jeep attracts a lively crowd of children in Yokohama a few weeks after the first occupation forces arrived.

The first small advance contingent of U.S. forces landed in Japan on August 27 (the day the minister of war issued his statement declaring that an orderly surrender was “our opportunity to display the magnificence of our nation”). MacArthur arrived three days later, taking care to be photographed disembarking from his plane at Atsugi airfield unarmed and with his trademark corncob pipe. Three days after that, on September 2, came the celebrated surrender ceremony in Tokyo Bay, which included a stunning display of the might of the forces that had crushed Japan—the sea choked with warships, the sky slashed by endless flyovers of fighter planes. The emperor’s representatives signed the instrument of surrender on this occasion, formally agreeing that the emperor and Japanese government were obliged to comply with the dictates of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.

86. An American sailor on a borrowed bicycle passes a ruined building near Yokosuka naval base in the closing days of August 1945, virtually simultaneously with General MacArthur’s serene arrival.

MacArthur’s “message to the American people” on September 2 was comforting to the Japanese, for it spoke of redirecting “the energy of the Japanese race” and gave assurance that “if the talents of the race are turned into constructive channels, the country can lift itself from its present deplorable state into a position of dignity.” There was, at the same time, neither promise nor expectation of a soft occupation policy. The lengthy “U.S. Initial Post-Surrender Policy for Japan” received on August 29 addressed punitive measures (war-crimes trials, reparations, etc.) but focused greatest attention on spelling out the broad, ambitious objectives of political and economic demilitarization and democratization. This basic policy statement was released to the public by the State Department on September 24, thus enabling the Japanese to read what only a few weeks earlier had been a secret internal U.S. government document.20

87. In this snapshot of an American soldier from the opening days of 1946, the bicycle remains, but the parasol has been exchanged for an attractive young woman.

Almost overnight, “SCAP” became a ubiquitous acronym throughout Japan, signifying both MacArthur personally and the overall military government over which he presided. Prior to the end of the occupation in April 1952, SCAP issued around twenty-two hundred highly specific orders known as SCAPIN (from Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers Index), along with another seven thousand “administrative” directives (known as SCAPIN-A). As rechanneled through the Japanese government, these became transformed into over five hundred “Potsdam orders” (potsudamu meirei). Of particular influence in shaping public understanding early on was a SCAPIN issued on October 4 ordering the Japanese government to undertake “Removal of Restrictions on Political, Civil, and Religious Liberties”; this included itemization of laws to be abrogated. One week later, MacArthur released a concise personal statement to the government concerning rapid implementation of “required reforms.” Soon widely known as the “five fundamental rights” or “five great reforms,” these involved (1) “emancipation of the women of Japan through their enfranchisement”; (2) “encouragement of the unionization of Labor”; (3) liberalization of the educational system; (4) creation of a “system of justice designed to afford the people protection against despotic, arbitrary and unjust methods”; and (5) “democratization of Japanese economic institutions” to ensure wide distribution of income and ownership. This October 11 statement was prefaced with the observation that these reforms would “unquestionably involve a liberalization of the Constitution.”

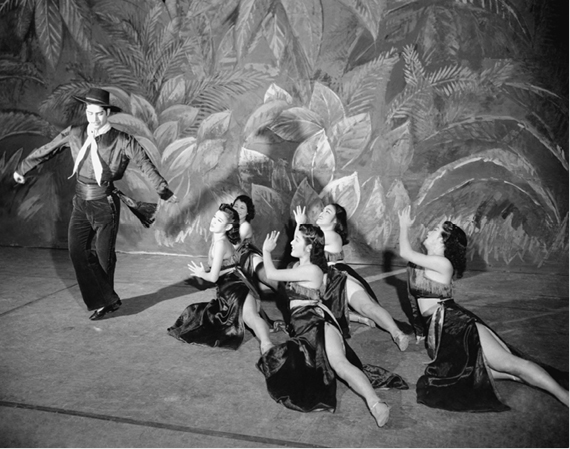

88. An astonished American photographer came upon this Japanese musical revue shortly after New Year’s Day of 1946. Such Western-style productions were prohibited after Pearl Harbor. Their swift reappearance reflected both a sense of liberation and a light form of escapism from the hardships of daily life that continued, for most Japanese, for years after the surrender.

Additional reforms were introduced in the next few months. Holding companies of the great zaibatsu conglomerates were ordered dissolved in November, for example, while December saw directives disestablishing “state religion” (State Shinto) and introducing a sweeping land reform that essentially appropriated property held by large landlords and redistributed it among a rural population that until then had high rates of tenancy and low levels of subsistence. The first postwar general election in April 1946 attracted over three hundred largely new (and ephemeral) political parties and saw the election of thirty-nine women to the lower house of the Diet. The ensuing session of the legislature spent many months discussing and tinkering with the radical constitutional revision that an impatient SCAP headquarters pressed on the Japanese government in February. (The new constitution was promulgated in September, came into effect in February 1947, and remained unrevised when the invasion of Iraq took place fifty-six years later.)

89. In April 1947, Life ran a five-page photographic feature re-creating scenes from UPI correspondent Earnest Hoberecht’s novel Tokyo Romance, a potboiler about an American journalist and Japanese movie star who fall in love. The book became a bestseller in Japan. In the scene staged here, the woman’s father looks on approvingly as her suitor proposes marriage.

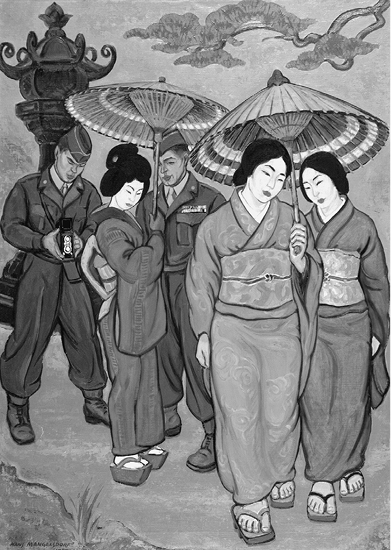

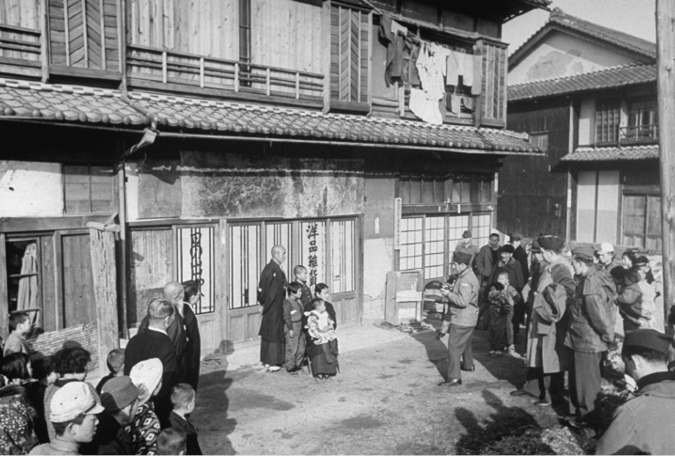

90. In this conspicuously self-referential mise-en-scène from January 1946, Alfred Eisenstaedt photographs a pretender to the imperial throne and his family, posing outside the modest store they ran. The allure of such unthreatening subjects led illustrated magazines like Life to devote almost insatiable attention to picturesque aspects of traditional Japanese culture and society. Geisha, temples and shrines, imperial duck hunts, tea ceremony, flower arranging, ceramics, cultivated pearls, bonsai trees, tattoos, Ainu aborigines, Kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, attractive rural and seaside locales, not to mention charming children and attentive women—all became magnets for media coverage of the erstwhile enemy.

Japan remained confronted by formidable problems and challenges for several years after the occupation began. The armed forces numbered close to seven million men at the time of surrender, for example, most of whom were overseas. Repatriation of these physically and emotionally exhausted individuals, plus hundreds of thousands of civilians, carried into 1947—and for some, even later. People continued to die of malnutrition after the surrender, often in public places like railway stations where the homeless gathered, and the incidence of diseases such as tuberculosis was abnormally high. Unemployment and inflation made making ends meet a struggle for most urban families until at least 1948, and the economy remained extremely precarious through 1949. It took time for the ruins of the burned-out cities to become replaced with new dwellings and workplaces, and dramatic recovery only arrived in the form of a war boom stimulated by the outbreak of conflict in Korea in June 1950 (prompting Yoshida to call the Korean War a “gift from the gods”).

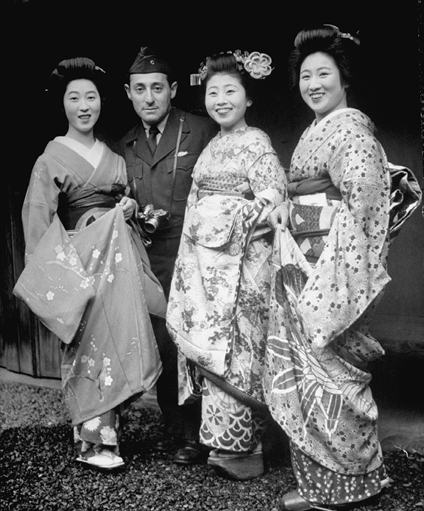

91. This February 1946 self-portrait by Eisenstaedt, posing with three geishas, goes beyond the merely picturesque and exotic to suggest the feminized and often eroticized relationship between victor and vanquished that emerged almost overnight. In the process of “winning the peace,” Japanese women cast a particular spell on non-Japanese males and contributed immeasurably to transforming the image of “Japan” that journalists and photographers transmitted back home. The wartime fixation on brutal Japanese fanatics—in President Truman’s characterization, collective and essentially incorrigible “beasts”—was replaced by fascination with a seductive society steeped in the gentle arts.

Certain reforms announced early on seemed slow to take hold, particularly at grassroots levels, and as time passed some occupation insiders held the democratization agenda up to critical public scrutiny. T. A. Bisson, an articulate left-wing participant in the implementation of economic democratization, addressed the shortcomings as well as accomplishments of the occupation in a 1949 book titled Prospects for Democracy in Japan, for instance, while two years later a more pessimistic American who had been involved in reforms at the local level produced a dour text titled Failure in Japan.21

At the same time, however, journalists churned out colorful and optimistic articles from the moment of MacArthur’s arrival, and before long a parade of anecdotal books hit the market with jaunty titles like The Conqueror Comes to Tea (1946), Star-Spangled Mikado (1947), MacArthur’s Japan (1948), Fallen Sun (1948), Popcorn on the Ginza (1949), Kakemono: A Sketch Book of Postwar Japan (1950), and Over a Bamboo Fence (1951, by the wife of a U.S. officer). Beginning in 1946, Earnest Hoberecht, a young UPI correspondent in Tokyo, became a minor celebrity by producing a few potboilers about love affairs between a Japanese woman and American man. Although written in English, these were immediately translated into Japanese and found an avid audience among female readers, who, it was reported, were particularly interested in his descriptions of kissing. Hoberecht’s best-known offering, titled Tokyo Romance, had sold over two hundred thousand copies by April 1947 when Life magazine—even while describing it as “possibly the worst novel of modern times”—devoted a five-page photo feature to a reenactment of this “tale of interracial romance.” (Tokyo Romance led a male Japanese reviewer to conclude that “the people of America must be intellectual midgets.”)

While these various pleasantries were drawing attention, scores of thousands of postcards and letters from ordinary Japanese were pouring into U.S. occupation headquarters, addressed to MacArthur personally or his command more generally. The vast majority were positive and even effusive in tone, and more than a few were accompanied by small gifts. Japanese admirers assembled daily to see MacArthur stride out of his Tokyo headquarters at noon and walk to his limousine (he was going home for lunch and a nap), and it was only a matter of months after the surrender ceremony before higher-ranking military and civilian personnel were having their families join them for what turned out, for most of them, to be an exotic and warmly remembered interlude. Cordial and productive relations were established early on with a wide range of capable mid-level Japanese bureaucrats, and morale was generally high, at least until the reverse course was introduced. By the end of the first year, there was already a great deal of self-congratulation that the ambitious agenda of social engineering was successfully underway. By the end of the second year, virtually all of the reforms now regarded as central to Japan’s emergence as a postwar democracy were in train—including not only the “five fundamental rights” but also other truly radical measures such as land reform.22

Discipline, moral legitimacy, well-defined and well-articulated objectives, a clear chain of command, tolerance and flexibility in policy formulation and implementation, confidence in the ability of the state to act constructively, the ability to operate abroad free of partisan politics back home, and the existence of a stable, resilient, sophisticated civil society on the receiving end of occupation policies—these political and civic virtues helped make it possible to move decisively during the brief window of a few years when defeated Japan itself was in flux and most receptive to radical change.

Much of this seemed routine and even mundane, until the absence of such attitudes and practices in occupied Iraq suddenly made them seem exceptional.

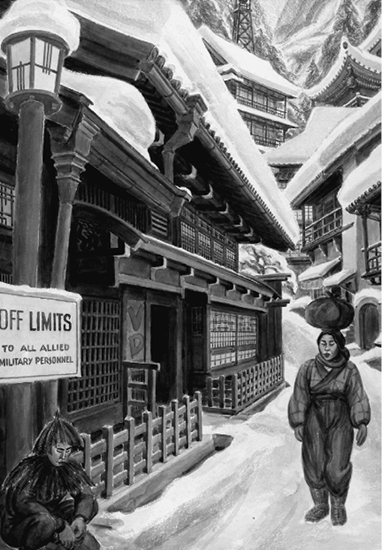

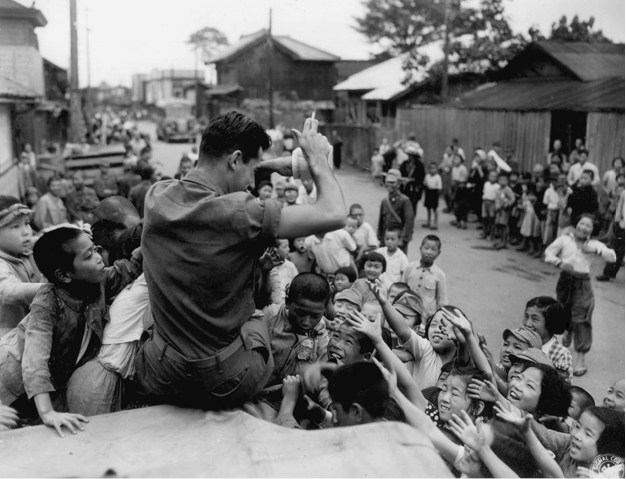

Eyes Wide Shut: Occupying Iraq

Vignettes often epitomize grander circumstances, and in occupied Japan one of the most recurrent of such scenes involved candy. Among the photographs we have of conquerors and conquered encountering each other for the first time is a street scene of children in ragged clothing crowding around an unarmed GI who is passing out sweets, while other Japanese including adults look on from a distance. The date is September 1945 and the place Yokohama.

“Give me chocolate,” one of the first English phrases Japanese children learned, has become indelibly associated with the occupation and still carries a multilayered ambiance. The killing had ended, and for good. Many GIs were friendly and kind. The Japanese were no longer the faceless, fanatical “beasts” that had to be, and deserved to be, indiscriminately incinerated. There was, moreover, more to the picture. Chocolate was also a symbol of the well-being, even the wealth, of the victors. Virtually all the children who clamored for candy and chewing gum then and for years after were malnourished, and sweets had disappeared from their lives. The Americans could (and did) provide what the nation’s leaders and children’s own parents could not.

Photographers accompanying the invasion forces usually dwelled on urban devastation, the awesome evidence of U.S. airborne destruction that had never been seen close-up by the bombers before. Destitute Japanese peopled these ruins, but photos only rarely dwelled on the burned or otherwise maimed; it was as if the bombs had destroyed only physical structures. In this setting, scenes of picture-perfect GIs surrounded by charming youngsters clamoring for candy reassured Americans back home about the innate gentleness of their fighting men—and more. Especially when set alongside another favorite subject of the earliest postwar foreign photographers—Japanese women—yesterday’s enemy abruptly became nonthreatening. In American eyes, such images helped push aside the brutal immediate past and clarify the mission that lay ahead. The children were the future, the adults pliant, the culture exotic but fundamentally effeminate, peaceful, and receptive—and the new role of the victors was clear. They were now called on to be patient and paternalistic, teachers about democracy and agents of sweeping change.

In these resonant ways, the iconic little scene of GIs passing out chocolate was simultaneously sweet and bittersweet, as well as propagandistic. In any case it was peaceful, and in this respect a fair representation of the nation’s interlude under American rule. The proclamations and preparations of Japan’s leaders prior to the arrival of occupation forces were successful, and there was no violence against the foreigners when they moved in. Not a single American was killed, then or later. The street scene photographed in Yokohama just weeks after the first of the victors arrived could and would be taken at numerous other times and places during the long occupation period.23

Sweets also became a kind of synecdoche for occupied Iraq, albeit in this instance in an anecdotal and notorious way. Iraqi exiles assured President Bush that the invading force would be greeted with sweets and flowers, and no one at top levels seriously questioned this. Certainly no one imagined the flowering of improvised explosives instead, eventually in numbers almost beyond counting. There was relief and rejoicing that the dictator had been overthrown, and many Iraqis did extend warm greetings to the military forces that brought this about; but such gratefulness passed quickly. The imagined sweets and flowers survive as a dream, but in an unexpectedly disturbing way: for the Bush administration’s planning—or, more accurately, negligible attention to serious planning—for postwar Iraq reflected the same dreamlike quality writ large. The planners who drafted and executed policy for postwar Japan would have found such almost romantic carelessness astonishing.24

The lessons that should have been drawn from postwar Japan—that occupations aimed at transforming an authoritarian society require not only clear legitimacy and enough space and time to innovate, but also administrative continuity, social cohesion, and experience in the workings of civil society on the part of the occupied—were not arcane or the special province of academic specialists. President Bush may have initially assumed that, like his own former sinful self, Iraq could and would be reborn overnight, but his advisers knew better—and then ignored what they knew. They disregarded not only forbidding social, political, and religious conditions that were taken seriously at the time of the first Gulf War, but also incisive warnings from lower-level officials as well as nongovernmental sources.

Postwar Japan was not really a serious model in anyone’s thinking, but rather another example of the administration’s penchant for using history ideologically. What should have been the red light of the “occupied Japan” example became instead one more green light aimed at speeding up the propaganda traffic; and leaders at the top became dazzled by their own spin.

IN A WORLD of less cognitive dissonance, two occupations that should have drawn attention were cases closer in time and place: the festering wound of territories occupied by Israeli settlers after 1967, and the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan from 1981 to 1989, which precipitated not merely the emergence of the mujahideen and subsequent rise of the Taliban but also the collapse of the Soviet Union. To lightly choose to invade and occupy yet another region in the Middle East in the face of such precedents, and without intense contingency planning, was hubris bordering on madness.

In theory, the war planners finally got around to formalizing thinking about post-combat challenges on January 20, 2003, two months before the invasion, when the president signed a secret directive establishing an “Iraq Postwar Planning Office” within the Defense Department. Retired lieutenant general Jay Garner, to his surprise, was recruited a few weeks earlier to head this unit, which was rechristened Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance (ORHA). Its mission was defined as “to help meet humanitarian, reconstruction, and administration challenges facing the country in the immediate aftermath of the combat operation”; its staffing was left largely to Garner, who prior to his recruitment had been CEO of a private company; and its projected budget was unspecified. There was nothing in these instructions about governance, and it was understood that Garner’s appointment would be for a limited duration. L. Paul Bremer III, who replaced Garner and set up the more authoritative Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) the following May, later characterized the ORHA as “a civilian rapid reaction force, a fire brigade, responsible for meeting immediate needs” that did not in fact immediately materialize, such as epidemics, food shortages, refugee flows, or damage to the oil fields by sabotage.25

One month after the presidential directive, Garner’s team conducted what is known in army parlance as a “rock drill” at the National Defense College, attended by around two hundred individuals. The twenty-page report that emanated from this was not encouraging. “We risk letting much of the country descend into civil unrest [and] chaos whose magnitude may defeat our national strategy of a stable new Iraq,” the report noted. And again: “We risk leaving behind a great unstable mess with potential to become a haven for terrorism.” And again: “The conference did not take up the most basic issue: What sort of future government of Iraq do we have in mind, and how do we plan to get there?” While Garner’s team was conducting its drill, officers in CENTCOM (U.S. Central Command, responsible for the Middle East and Central Asia) stationed in Doha on the Persian Gulf, on whom immediate post-invasion responsibilities would fall, issued a report pointing out that the war plans they were receiving were contradictory. Since the shock-and-awe offensive that preoccupied war planners was designed to “break all control mechanisms of the regime,” they argued, it made no sense to talk about relying on Iraq’s indigenous structures of command and control to ensure post-invasion stability. Absent a concrete U.S. plan for stabilization, Iraq faced the risk of disruptive activity by criminals and former regime members as well as “an influx of terrorists.”26

These problems had been anticipated within the bureaucracy many months earlier, particularly among officials skeptical of the headlong rush to war. In September, for example, the Policy Planning Staff in the State Department finalized a fifteen-page, single-spaced memorandum titled “Reconstruction in Iraq—Lessons of the Past,” based on over twenty cases of post-conflict reconstruction in the twentieth century. Unlike Afghanistan, this report argued, invading Iraq would require (in the retrospective summary words of Policy Planning Staff head Richard Haass) “a large-scale, long-term occupation.” “Reconstruction in Iraq” opened with the timeworn cliché about winning the peace (“If we end up going to war with Iraq, we need to be prepared to win the ensuing peace”); called attention to deep indigenous challenges to national unity, and the need to “prevent a security vacuum after Saddam’s ouster”; and offered a highly cautionary balance sheet of the baseline of “hardware” and “software” Iraq possessed that would be essential for its emergence as a stable and relatively democratic state.

In developing its analysis, the Policy Planning Staff introduced a buzzword that was anathema in the conservative and neoconservative circles that influenced the administration’s planning: nation building. Its country studies ran a gamut of possible post-conflict agendas ranging from “nation building lite” to “full-scale nation building,” with the reconstruction of Europe and Japan after World War II being “examples par excellence” of the latter. In all likelihood, the invasion of Iraq would require “a more ambitious post-conflict reconstruction” than the administration appeared to be envisioning—even, despite obvious differences, something commensurate with what took place in Japan and a few other nation-states, such as South Korea, Greece, Italy, and postwar West Germany. (This thesis also was rendered in diagrammatic form in the report.) Easily imagined negative scenarios in a post-Saddam Iraq—a “chaotic post-conflict environment” domestically; the perils of living in a “troubled neighborhood” geographically; tensions between political players inside the country and a fractious “opposition in exile”; the absence of “recognized national figures—like Emperor Hirohito” who might provide a unifying symbol—all called for careful planning and intensive post-invasion engagement.

In conclusion, the report rejected the “MacArthur model” of occupied Japan as too costly as well as too vulnerable to being “perceived as a crude imperial grab for oil and power in the Middle East.” What it endorsed instead was approaching reconstruction as a genuinely international effort involving nations, international organizations, and nongovernmental organizations—strongly led by the United States, but “operating typically under a UN mandate” and ideally headed by “an experienced and reliable non-American—and preferably non-Westerner”—with a UN title. Instead of one poison pill, the State Department’s planners thus embedded two in their recipe for the occupation and reconstruction of Iraq (“nation building” and “internationalism”). Given the overwhelming fixation in the White House and Pentagon on a quick shock-and-awe, in-and-out war controlled start to finish by the United States, this was a document virtually guaranteed to sink quickly from sight. Secretary of State Colin Powell sent it to his counterparts in the Defense Department, the NSC, and the Office of the Vice President, but it never received a serious hearing in interagency deliberations.27

This was also the case with another, better-known initiative undertaken elsewhere in the State Department in the latter half of 2002: a “Future of Iraq Project” that eventually enlisted around a hundred mostly expatriate Iraqi experts (routinely identified as “free Iraqis”) in various fields. This evolved into seventeen working groups and, by year’s end, over a thousand pages of diffuse reports that might be very loosely compared to the handbooks and civil affairs guides for Japan produced under SWNCC during World War II. One report (by the working group on transitional justice) warned that “the period immediately after regime change might offer . . . criminals an opportunity to engage in acts of killing, plunder, looting, etc.” Another (by the working group on transparency and anti-corruption measures) emphasized that “the people of Iraq are being promised a new future and they will expect immediate results. The credibility of the new regime and the United States will depend on how quickly these promises are translated to reality.”28

Although the Future of Iraq Project mobilized considerable expertise, it did not pretend to offer a blueprint for occupation nor did it even succeed in offering a practical, coherent agenda. In the end, the reports became buried in the turf wars that set the State and Defense Departments in particular at loggerheads. The most “toxic” such fratricidal moment occurred in late February (the adjective is Douglas Feith’s), just weeks before the invasion, when Rumsfeld abruptly rejected Jay Garner’s concrete recommendations of senior U.S. advisers who could be immediately placed in Iraqi ministries to help stabilize and guide the transition to a post-Saddam government. The secretary of defense rejected the list out of hand primarily because it included too many specialists from the State Department. Even after the invasion was launched, Garner was essentially forced to fly blind. “I never knew what our plans were,” he confessed after being replaced by Bremer. An inside joke had it that ORHA actually stood for “Organization of Really Hapless Americans.” Black humor was irresistible, but it failed to capture the tragedy that resulted from such a stunted planning process, riddled by personal agendas and petty peevishness.29

As a consequence of such shortsightedness, post-invasion staffing and funding remained largely unresolved up to and through the point of invasion. Most of the debate on these matters remained in-house, but a few officers and officials—most famously General Eric Shinseki, the Army chief of staff, in late February—publicly challenged the low troop projections and low estimates of how costly the entire operation, including the endgame, would be. They were publicly rebuked for stepping out of line (“outlandish” and “wildly off the mark” was Deputy Defense Secretary Wolfowitz’s response). When Bremer was appointed head of the Coalition Provisional Authority two months later, the RAND Corporation, which had a long track record of providing security studies to the government, handed him a lengthy study of previous occupations (including Japan and Germany) that concluded that ensuring security requires a ratio of twenty U.S. troops for every thousand people in the occupied country. Where Iraq was concerned, this translated into five hundred thousand troops—more than three times the number the White House planners assigned. Bremer passed this on to the president as he was leaving for his new post, and also to the secretary of defense. Although by this date occupied Baghdad was burning, he never received a response.30

Researchers accustomed to sifting through the old-fashioned typescript and carbon-copy documents of the World War II era encounter a conspicuous time warp when it comes to the fragmentary accessible documentation of planning “regime change” in Iraq. There are indeed cogent reports and papers. There is also an addiction to “bullet point” list making that reflects both the technical advances of a PowerPoint age and the scattershot thinking that too often accompanies this, confusing inventories of discrete “points” and queries with careful deliberation and clear conclusions. Lists, memos, working papers, and endless rounds of PowerPoint and slide presentations do not in themselves constitute coherent policy formulation. Nor do “plans” approved at high levels that in practice are ambiguous and even internally contradictory—the “bridging proposals” that Condoleezza Rice often crafted for the National Security Council to preserve an appearance of harmony and consensus. While the planning for combat operations was meticulous, the attention devoted to operational preparation for post-combat stabilization and reconstruction rarely went beyond the bullet-point level.31

The hoped-for scenario that ultimately guided the war-planning process was elemental to a fault: destroy Saddam’s command and control, rely primarily on the Iraqi military and police for security, “bring new leadership . . . but keep the body in place” (in Rice’s phrasing), hope that other nations would volunteer for postwar tasks, and withdraw most U.S. troops within two or three months. In Rumsfeld’s Pentagon, the guiding mantra was to keep a light or small military “footprint” in Iraq—as already had been done in Afghanistan. As more cautious analysts in and outside the government were pointing out, however, if the despotic regime was decapitated, and looting and chaos were predictable, and it was dubious that the infrastructure would be intact, and it was uncertain where exactly new leadership would come from, and the situation in and around Iraq was already a tinderbox—then exactly who was to be primed to do what? No one knew. Garner’s overwhelmed ORHA staff, at their late-February “inter-agency rehearsal and planning conference,” observed that overshadowing questions of staffing and funding and what to do immediately to ensure law and order was the larger “critical issue” of civil administration: “Footprint to be small or large?”32

Virtually all critical accounts of preinvasion thinking about postwar Iraq, by both insiders and investigative journalists, reach the same conclusion: “There is a misconception that we were rehearsing a plan. There was no plan” (Colonel Paul Hughes, a member of the ORHA team). “There was no real plan. The thought was, you didn’t need it. The assumption was that everything would be fine after the war, that they’d be happy they got rid of Saddam” (Lieutenant General Joseph Kellogg Jr., a senior member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff). “The United States government didn’t have something ready to go the day after. It didn’t have a clear-cut concept of how it was going to proceed and that we could put in play immediately” (Edward Walker, assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs at the time). “We did not have a well-developed theory of how best to produce legitimate democracy in Iraq. Indeed, famously, when the war began, we did not even have a plan” (Noah Feldman, senior constitutional adviser to the CPA).33

Viewed from this larger perspective, the “occupied Japan” mirage becomes just another small piece in the jigsaw of delusion and self-delusion that marked the rush to war. Somehow there would simply be a happy landing in Iraq, as there had been in Japan and Germany after World War II—indeed, a happier landing, since the administration’s projections envisioned withdrawing most troops quickly (while at the same time establishing, as in Japan and Germany, essentially permanent military bases). This was not only faith-based policy making but also a reflection of something else: a deep ideological aversion to the concept of social engineering or nation building that lay at the heart of the earlier occupations of Japan and Germany and had been central to the State Department’s disregarded September 2002 report.

The administration was trapped by rhetoric: how could one even use the word, let alone plan the reality of an “occupation” of Iraq when what was taking place was “liberation”? But beyond this, how could an administration whose core philosophy and core constituencies defined “freedom” primarily in terms of unrestrained markets and optimal shrinking of the role of the state commit itself to planning and promoting a reasonably equitable and democratic new Iraq? Noah Feldman, who arrived in Baghdad at almost the same time Bremer did, put it succinctly. “This was an administration that didn’t want to do nation-building,” he told an interviewer after returning. “Immediately on the fall of Saddam, they said, a new government could emerge. Somewhat by magic.”34

One of Rumsfeld’s brusque habits as an administrator involved sending staff and colleagues memos on whatever drew his attention at the moment. These became known as “snowflakes,” and the defense secretary produced between twenty and as many as one hundred of them daily. By the time he resigned following the congressional elections of 2006, the accumulated snowdrift amounted to around twenty thousand memos. One snowflake, dated March 10, 2006, reflected chagrin that opinion polls indicated two-thirds of Americans had concluded that the United States never had a plan for victory in postwar Iraq. “We need a better presentation to respond to this business that ‘The Department of Defense had no plan,’ ” Rumsfeld fumed to his assistant secretary for public affairs. “That is just utter nonsense. We need to knock it down hard.”

In a snowflake that fell earlier (in May 2004), Rumsfeld mused over whether terrorism should be redefined as a “worldwide insurgency” and went on to suggest that one of the reasons things were getting out of hand was that Muslims were lazy. Oil wealth often detached them “from the reality of the work, effort, and investment that leads to wealth for the rest of the world,” he wrote. “Too often Muslims are against physical labor, so they bring in Koreans and Palestinians while their young people remain unemployed.” How did this account for rising insurgency? “An unemployed population is easy to recruit to radicalism.”35

Frivolous ideas of the latter sort usually melt before touching paper or the computer screen—but not in an administration unable to contemplate any possible relationship between its own actions and a spiraling incidence of terror and insurrection in Iraq and elsewhere. Rumsfeld’s vexation at hearing the Pentagon accused of having had no postwar plans, on the other hand, is somewhat more understandable: surely there was a plan somewhere in that blizzard. Keeping a small footprint was a plan. So was supporting some sort of “Iraqi Interim Authority” dominated by exiles and “externals.” President Bush actually signed such a plan emanating from the Pentagon on March 10, nine days before the invasion, after it had passed through the NSC—although this was kept secret even after U.S. forces entered Baghdad, and ultimately largely ignored by everyone, including the president, who briefed Bremer in May.36

Certainly, the question of post-hostilities “occupation” had been addressed on many occasions, albeit always with a double edge. On the one hand, the president’s top advisers discussed the perils of foreign occupation. A State Department paper submitted to the NSC on July 25, 2002, under the title “Diplomatic Plan for the Day After,” for example, warned that if the United States became depicted as an “occupying power,” the result “would likely be delegitimized government; instability . . . and possibly terrorist acts—against U.S. forces.” This was recycled shortly afterwards in a paper titled “Liberation Strategy for Iraq” that Rice’s NSC submitted to the Principals Committee. Here the warning became “We do not want the world to view U.S. actions in Iraq as a new colonial occupation.” State’s September warning about the perils of imposing the “MacArthur model” in Iraq echoed this concern about avoiding any appearance of being engaged in an “imperial grab” for power and profits in the Middle East. Months later, when the machinery behind Operation Iraqi Freedom was almost in full train, the CIA raised the same warning, noting that “Iraq’s history of foreign occupation . . . has left Iraqis with a deep dislike of occupiers. An indefinite foreign military occupation, with ultimate power in the hands of a non-Iraqi officer, would be widely unacceptable.”37

MISSIONS ACCOMPLISHED AND UNACCOMPLISHED

On May 1, 2003, some six weeks after launching Operation Iraqi Freedom, the Bush administration celebrated victory on the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln “at sea” off San Diego. The president arrived by helicopter wearing full pilot’s gear, before changing to civilian attire and announcing the end of major combat operations beneath a banner reading “Mission Accomplished.” This celebration was modeled on the ceremony that took place on the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, presided over by General MacArthur, but atmospheric similarities paled before the differences between the two occasions. The Japanese government formally surrendered beneath the Missouri’s big guns, and representatives of all the victorious Allied powers were present. For Japan, the killing and dying was over. For Iraq, a spiral of instability, occupation, terror, and insurgency had just begun.

94. Japanese officials sign the instrument of surrender aboard the USS Missouri, September 2, 1945.

95. The nuclear-powered supercarrier Abraham Lincoln off San Diego, with the “Mission Accomplished” banner displayed on its superstructure.

96. This official group photograph with the carrier’s deck crew nicely captures the Hollywood-style scripting of George W. Bush as a “war president.”

At the same time, however—and often in the same discussions and reports—it was emphasized that once Saddam had been overthrown, the United States might find it necessary to remain deeply engaged in ensuring Iraqi stability, reform, and reconstruction for, not just a few months, but at least a year or more. Thus, the same August NSC paper on “Liberation Strategy for Iraq” that warned about the backlash if the invasion led to perception of the United States as “a new colonial occupation” also stated—without resolving or even highlighting the contradiction—that “the one option for regime change which gives the most confidence in achieving U.S. objectives is the employment of U.S. forces to accomplish regime change, staying in significant numbers for many years to assist in a U.S.-led administration of the country.”38

These were not just practical issues that awaited resolution by pragmatic planners. They were deeply ideological, for ultimately they posed the question of the proper role of the military—and, beyond this, of the state. When Pentagon planners used the “light footprint” shorthand, they had in mind more than just the lean, high-tech military machine that mesmerized proponents of the “revolution in military affairs.” This also was shorthand for avoiding deep engagement in nation building—that is, in the sort of wide-ranging and long-term social engineering that had been undertaken under military auspices in Japan and Germany. Opposition to nation building—with all its connotations of the state playing an enormous role in development, and indeed in political, economic, and social development abroad—was part of the agenda on which Bush ran for the presidency in 2000 (the key speeches were in October), and Condoleezza Rice, his foreign-policy adviser in the campaign, was instrumental in shaping this view.

Repudiation of nation building became one of the several rocks on which post-hostilities planning was wrecked. (Whether to support Iraqi exiles in a transitional government was another.) Two examples—an exchange involving the national security adviser, and an eve-of-invasion speech by the secretary of defense—graphically capture the attitude that ultimately prevailed in ruling circles. In October 2002, several think tanks proposed to Rice, as head of the NSC, that they work together to offer policy options for postwar Iraq. The groups initially proposed—the Council on Foreign Relations, Heritage Foundation, and Center for Strategic and International Studies—brought various political outlooks to the table, and Rice responded positively. (“This is just what we need,” one account quotes her saying. “We’ll be too busy to do it ourselves.”) Rice was not supportive of the Heritage Foundation, which was critical of the Iraq war idea, however, and recommended bringing in the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) instead. The latter was a strong supporter of the pending war.

Representatives of the think tanks met with Rice at her White House office the following month in a meeting that marked the end rather than the beginning of this initiative. After Leslie Gelb of the Council on Foreign Relations presented the case for laying out options for an overall post-conflict policy, the president of the AEI intervened to chastise Rice for even considering this. “Does Karl Rove [Bush’s senior political adviser and liaison to the political right] know about this?” Gelb quotes him saying. “Does the president? Because I don’t think they would approve. It sounds like a nation-building exercise, and they—and you yourself, Condi—have opposed such foolish Clintonesque policies time and again.”

And that was more or less the end of it. As Gelb told a reporter later, “They thought all those things would get in the way of going to war.” The episode survives as a snapshot of the self-proclaimed center of the world as the war clock ran down: an influential conservative lobby that prided itself on combining high ideals with tough-minded pragmatism assumed things would fall into place after a decisive demonstration of military might, and such credulity carried over to the president and his highest advisers. They were not predisposed to acknowledge that, in the real world, things fall apart more easily than they fall into place.39

Rumsfeld brought the administration’s position to the public in an important speech titled “Beyond Nation Building” on February 14, 2003—a telling date in retrospect, for this was precisely when military and civilian officers at many levels were raising alarms about losing the peace. The occasion was an annual “salute to freedom” held at New York City’s Sea, Air & Space Museum, which is housed in the decommissioned World War II battleship Intrepid. Rumsfeld began by unpacking the rhetorical shopping bag of now-familiar interlocking images. The Intrepid played a critical role in the Pacific after Pearl Harbor, he pointed out, and sailors on its deck had looked on in horror as Japanese suicide planes crashed into the U.S. fleet. The link to September 11 followed naturally: “More than a half century later this entire ship once again witnessed heroism and carnage. From the deck on a clear September morning Americans could watch with horror as suicide bombers struck again—this time crashing into the Twin Towers.”

The analogies did not end there, of course. Rumsfeld described how the Americans fought back after Pearl Harbor and then went on and “helped the Japanese people rebuild from the rubble of war and establish institutions of democracy.” The contemporary parallel was fighting-back in Afghanistan after September 11, and here the secretary introduced his “beyond nation building” theme. Without mentioning Japan again, he evoked Afghanistan as a model for behaving “not as a force of occupation but as a force of liberation.” He spelled this out as follows: “The objective is not to engage in what some call nation building. . . . This is an important distinction. In some nation building exercises well-intentioned foreigners arrive on the scene, look at the problems and say let’s fix it. This is well motivated to be sure, but it can really be a disservice . . . because when foreigners come in with international solutions to local problems, if not very careful they can create a dependency.”