CONVERGENCE OF A SORT: LAW, JUSTICE, AND TRANSGRESSION

Almost exactly two years after the invasion of Iraq, the Defense Department released a major document—The National Defense Strategy of the United States of America—that contained a striking statement about U.S. “vulnerabilities” in the “changing security environment.” “Our strength as a nation,” this declared, “will continue to be challenged by those who employ a strategy of the weak using international fora, judicial processes, and terrorism.”47

At first glance, international forums and judicial processes may seem to be odd bedfellows to pair with terrorism. In fact, this pairing reflected concerns that troubled conservatives long before September 11—challenges sometimes addressed in and outside the Pentagon under the rubric of “lawfare.” After the Watergate scandal and Vietnam War, the lawfare argument maintained, political leaders, intelligence agencies, and military forces had become increasingly entangled in a web of laws promoted both domestically and internationally by human-rights groups and lawyers devoted to (as the critics saw it) the “criminalization of warfare.” Law itself had become a battleground.

The fervent endeavors to strengthen presidential powers under the name of a “unitary executive” that peaked in the Bush administration reflected this gnawing perception of becoming “strangled by law.” Predictably, 9-11 and the threat of future terrorist attacks propelled these concerns to almost frantic levels. The response—as expedited by the informal “War Council” of ultraconservative lawyers who secretly drafted the initial Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) opinions subsequently known as “torture memos”—was extreme, and ultimately left an indelible stain on both the presidency and the reputation of the United States. When Jack Goldsmith, a conservative lawyer who supported strengthening presidential power and endorsed declaring “war” on terror and denying “POW” status to prisoners, became head of the OLC in October 2003, he was distraught to find that these classified opinions were “deeply flawed: sloppily reasoned, overbroad, and incautious in asserting extraordinary constitutional authorities on behalf of the President.” Two months after assuming his post, Goldsmith recommended that the critical memos governing interrogation be withdrawn and reframed, but before this was done the ground shifted. The notorious photographs from Abu Ghraib prison made their way onto the Internet (in April 2004); the denial of habeas corpus to prisoners held at Guantánamo became a global scandal; “rendition” of terror suspects to countries where they would be brutally interrogated likewise became a scandal, as did the revelation of invasive electronic surveillance domestically; and some of the secret torture memos were leaked to the public (beginning in June 2004). It was too late to repair the damage; and, indeed, mostly too late to reel in the practices themselves.48

Jiggering the law is hardly new under the sun, and also took place at various levels in American and Allied conduct in World War II and its immediate aftermath. Legal constraints were looser then. Such manipulations and abuses received little negative publicity, and perhaps most decisively, thoroughgoing victory over atrocious enemies all but erased such transgressions from memory. By contrast, the many miscarriages of the war on terror made the Bush administration vulnerable to criticism of the sort that victors escape. So did the uncontrollable digital world of exposé, scandal, propaganda, polemics, and principled dissent. And so did the particularly arrogant swagger with which the Bush White House pursued its “unitary executive” vision of an imperial presidency free from external restraints, especially where national security and international affairs were concerned.

President Bush’s coarse manner of expressing himself only served to deepen the impression of contempt for the law. Typical was his exclamation to staff gathered in the White House emergency operations center on the evening of the September 11 attacks, as recounted by the NSC’s counterterrorism expert Richard Clarke: “I don’t care what the international lawyers say, we are going to kick some ass.” However precisely accurate this quotation may be, it was pitch-perfect in capturing the scorn for international treaties and the like that already had preceded 9-11, and the disdain for legal restraints that became even more intense thereafter. It was also pitch-perfect in capturing a disturbingly sophomoric response to an extraordinarily complex challenge.49

Even among a growing chorus of domestic critics, it usually was taken for granted that such reckless regard for the law was aberrant—a departure from the respect for rule of law that is supposedly a bedrock of American democracy. The perception of egregiousness was accurate, but it was not accurate to assume that America and its allies had been scrupulous in respecting human rights, civil rights, and international law in earlier conflicts. It took over four decades, for example, for Congress and the executive branch to acknowledge that the incarceration of some 110,000 Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor was a perversion of justice. (President Reagan signed the legislation apologizing for this in 1988.) Other areas in which established law was disregarded, circumvented, bent, or arbitrarily and substantially revised in conjunction with World War II remain largely ignored.

Like the legally questionable occupation of Iraq, the sweeping reform agendas imposed earlier on Germany and Japan disregarded existing conventions governing post-conflict occupations. What became an example of successful “demilitarization and democratization” for many observers, then and decades later, had no precedent in law or practice.

Similarly, the war-crimes trials conducted in Nuremberg and Tokyo and at scores of little-remembered military proceedings against thousands of less prominent former Axis enemies involved charges and procedures that have left a contested legacy. On the one hand, these trials introduced idealistic norms of war responsibility and accountability—in ways, indeed, that have returned to haunt the United States. At the same time, the war-crimes tribunals were riddled with procedural flaws and vulnerable to the accusation that they amounted to hypocritical exercises in “victor’s justice.”

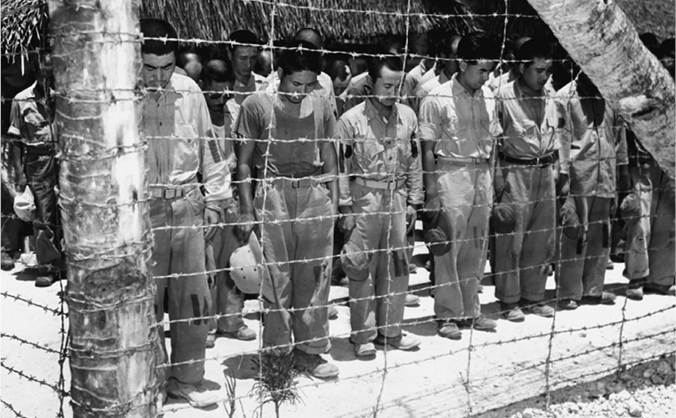

In yet another direction, in this instance remotely comparable to the Bush administration’s legalistic subterfuges and subsequent maltreatment of prisoners, the leading nations that claimed victory in Asia in 1945—including France, the Netherlands, and the Soviet Union along with the United States, United Kingdom, and China—all engaged in one form or another of abuse of surrendered forces. Hundreds of thousands of Japanese were denied swift repatriation, often for extended periods and sometimes fatally. Many were forced to perform labor for the victors, and tens of thousands were enlisted to participate in China’s civil war or the colonial struggles against indigenous independence movements that followed the collapse of Japan’s short-lived occupation of Southeast Asia.

These earlier abuses do not replicate the Bush administration’s evasions of the law, or mitigate them, but rather help place such transgression in a larger historical frame—and a larger, confounding milieu in which cynicism, pragmatism, “realism,” and even professed idealism may politicize the law and obstruct just practices.

Before World War II entered its endgame, the United States and Britain declared that the enormity of Axis crimes was sufficient justification for imposing sweeping changes within the enemy nations once they had been defeated. This was the rationale behind the concept of unconditional surrender announced by Roosevelt and Churchill in 1943 and adhered to in the German and Japanese surrenders. Briefly put, unconditional surrender had no legal precedent, and the extensive reform imposed in the Allied occupations that followed likewise had (in the words of an American scholar writing in 1949) “no place in accepted law on the subject and was strictly forbidden.” A standard text on occupation law published several decades later concurs that the acceptance of unconditional surrender “was critical to the Allies because it was generally accepted that the law of occupation did not condone the measures the Allies intended to implement in both Germany and Japan.”50

The central provision in accepted law in this regard was Article 43 in the Hague Regulations of 1907, which reads in full as follows: “The authority of the legitimate power having in fact passed into the hands of the occupant, the latter shall take all the measures in his power to restore, and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety, while respecting, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country.” In practice, “the laws in force” in defeated Japan, including the constitution as well as civil and penal codes, were subjected to wholesale revision, while the reform agenda in its entirety went far beyond anything previously deemed permissible to a foreign occupant—and certainly far beyond what was required to ensure public order and safety. The Hague Regulations also stipulated that property must be respected by the occupant—a provision that was severely challenged in occupied Japan by the land reform, dissolution of family-held zaibatsu holding companies, confiscation of property owned by organizations deemed to have been militaristic or ultranationalistic, termination of pensions to individuals purged as militarists, and the requisitioning of private residences and office buildings for use by occupation personnel.51

The legal basis of the occupation of Japan was, in fact, addressed confidentially in some detail within the U.S. government, and the legal limbo of the draconian policies initially adopted was, if not publicly broadcast, at least publicly acknowledged. An unusually frank two-volume tome on the “political reorientation of Japan” prepared by MacArthur’s staff and published by the U.S. government in 1949, while the occupation was still underway, observed that the occupation “presented a new problem in international law”: the surrender was “total”; the Japanese government remained in power; the goal was to “ensure a peaceful Japan” once foreign forces were withdrawn; and—here frankly acknowledged and fully quoted—Article 43 of the “Hague rules” explicitly prohibited altering the basic domestic laws of the occupied nation. “It has very generally been accepted that the military occupant exercises military authority over the occupied country but does not have full rights of sovereignty,” this analysis continued. “How far the total surrender, made with full knowledge of the intentions of the victors, would operate to change this rule has never been established.”52

In Japan, as in Iraq decades later, establishing respect for “rule of law” was a cardinal tenet in rationalizing democratic reform. This extended, insofar as public relations was concerned, to international law. Thus, in mid-December 1945, four months into the occupation, the Public Relations Office of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers assured the Japanese that “the civilian population will be kept free from all unwarranted interference with their individual liberty and property rights. . . . The occupation forces will observe the obligations imposed upon them by international law and the rules of land warfare.” When push came to shove in the exercise of actual authority, however, the latter piety in particular was really honored only in the breach. As previously noted, the decisive instructions in this regard had been submitted to MacArthur by Truman three months earlier, on September 6, and explicitly affirmed that “our relations with Japan do not rest on a contractual basis, but on an unconditional surrender. Since your sovereignty is supreme, you will not entertain any question on the part of the Japanese as to its scope.”53

THERE WAS NO precise counterpart in Iraq to the wartime pronouncements and post-hostilities documents the Americans used to legitimize their nation building in Japan: no principle of unconditional surrender, no formal terms and signed understandings equivalent to the Potsdam Declaration and Instrument of Surrender. In the weeks after Operation Iraqi Freedom was launched, U.S. authorities still refused to acknowledge they were engaged in a “military occupation”; and even when the United States and United Kingdom designated themselves the Coalition Provisional Authority and solicited the support of the UN Security Council (on May 8, 2003), they avoided speaking of themselves explicitly as “occupying powers.”

It was not until the Security Council responded with the enabling Resolution 1483 on May 22, two full months after the invasion, that the “occupying powers” phrase was first formally used—and, as shepherded through the United Nations by the two powers, the resolution only served to make the legal waters more rather than less opaque and problematic. It began by “reaffirming the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Iraq,” and then proceeded—astonishingly and foolishly in the view of some legal scholars—to emphasize that occupation authorities must “comply fully with their obligations under international law including in particular the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the Hague Regulations of 1907.”54

In the appraisal of Eyal Benvenisti, author of a major text on the international law of occupation, Resolution 1483 awakened “from its slumber” a body of laws that had been formulated in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, and “required that politicians and lawyers revive an old doctrine that in the last half century almost reached the state of desuetude.” In the view of David Scheffer, who served as the Clinton administration’s first ambassador-at-large for war-crimes issues, this ill-conceived attempt to use the United Nations to essentially confirm Anglo-American dominance over that international body where Iraq was concerned invited legal blowback. Scheffer, who supported the need for “bold and transformational control” over post-Saddam Iraq, concluded that by assigning the responsibilities of being “occupying powers” to the United States and Britain while affirming the applicability of the Hague and Geneva laws, Resolution 1483 actually laid the two occupying powers open to no less than twelve different areas of potential “civil liability or criminal culpability under occupation laws.”55

Scheffer, focusing purely on legal issues, was taken aback by the carelessness with which these consequential matters had been “left on the shelf” during the long period of U.S. war planning—and then, like so much else pertinent to post-invasion order and security, and post-Saddam “nation building,” were belatedly addressed so incompetently. This sort of criticism never arose in a public way when the American-led occupiers in Japan were gliding over the “Hague rules” like skaters. Still, the cavalier ethos of seizing sovereign power even while affirming respect for existing law including the Hague Regulations was comparable. Thus, despite Resolution 1483’s reassuring opening words about respecting the sovereignty of Iraq, when CPA head Paul Bremer convened his first meeting with newly appointed Iraqi ministers four months later (on September 16), he more or less reprised Truman’s message to MacArthur almost sixty years earlier. “Like it or not,” he told the new ministers, “the Coalition is still the sovereign power here.” And so it remained, with crippling political and psychological consequences, for another nine months.56

War Crimes and the Ricochet of Victor’s Justice

In Japan, as later in Iraq, the legality of the occupation was at best of passing interest, since disregard of the Hague Regulations quickly became a fait accompli and the defeated nation eventually did regain sovereignty. More controversial was the prosecution of so-called Class A war criminals in Tokyo—the counterpart to Nuremberg formally known as the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. These celebrated trials of German and Japanese civilian and military leaders had several goals, apart from simply punishing men who had unleashed horrendous aggression and atrocity. One long-term objective concerned the historical record: the trials provided a vehicle for assembling a documentary and testimonial record of such breadth and detail that future nationalists and apologists would be hard pressed to deny the transgressions committed by Nazi Germany and imperial Japan.

The second, more compelling goal was nothing less than to establish a new realm of international law that would hold individual leaders accountable for egregious acts of state—and, thus, ideally deter future acts of aggression. Such “deterrence” thinking amounted to a nonviolent complement to the earlier argument among strategic planners that using the atomic bombs would help stimulate postwar arms control and prevent future wars. Like unconditional surrender, this activist conception of the war-crimes trials entailed ignoring precedent—and, it followed, indicting defendants for transgressions that did not exist as crimes when they were allegedly committed. Holding individual leaders accountable for acts of state before an international tribunal was itself precedent-setting. The German and Japanese trials also introduced two new categories of war crimes—against “peace” and against “humanity.” For obvious reasons, the specific itemization of Axis war crimes, including violation of established regulations and conventions, excluded acts such as the deliberate bombardment of civilian populations.57

“Crimes against humanity” was introduced at Nuremberg primarily to address the Holocaust, and did not play a significant role in the Tokyo tribunal. “Crimes against peace,” on the other hand, was translated into conspiracy to wage aggressive war and applied to everything the Japanese had done abroad militarily since 1928. The “conspiracy” charge also was unprecedented in international law, and amounted to a grossly simplistic explanation of the upheaval in Asia (and within Japan itself) from just before the Great Depression to the end of the war seventeen years later. No serious historian of prewar and wartime Japan today would endorse this argument.

Like Nuremberg, the Tokyo tribunal involved a great deal of juridical idealism. This trial of twenty-eight high-ranking defendants (twenty-five by the trial’s end) dragged on from mid-1946 to the end of 1948, and the defense actually was allowed to take more time than the prosecution to present its case. Nonetheless, these proceedings predictably opened the door to charges of illegality, double standards, and victor’s justice that never have ceased to outrage Japanese conservatives and nationalists. Imperial Japan’s military operations were undertaken in response to Western imperialism as well as to “chaos and Communism” in China that threatened Japan’s essential economic interests there, these critics insist, employing the argument of self-defense common to defenders of aggression everywhere. The rallying cries of liberating Asia from Western imperialism and colonialism were sincere, and not merely propaganda masking naked self-interest. And where atrocities occurred, these largely reflected the unplanned excesses that take place on all sides in all wars. They were—again in a formulaic argument familiar to most zealots and patriots when explaining away their own crimes—aberrations.

There was no real counterpart in Iraq to the war-crimes trials of Germans and Japanese—and no corresponding attempt to use such a platform to subpoena documents and assemble testimony that would help establish a dense and optimally comprehensive record of the transgressions of the regime now placed in the dock. The disorderly trial and execution of Saddam Hussein focused on a fragment of the dictator’s crimes and amounted, in the end, to little more than political theater.58

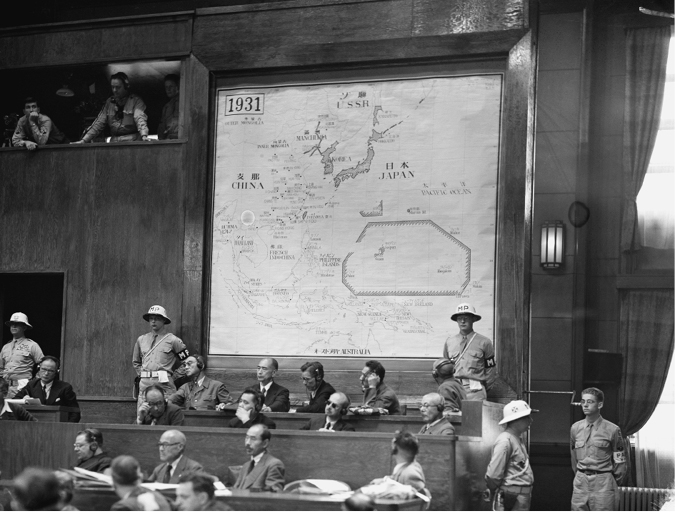

103. Defendants at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East sit in front of a rotating display of huge maps depicting the Japanese empire between 1928 and the surrender. Beyond introducing new standards for prosecuting war crimes, another objective of these elaborate proceedings was to compile a detailed documentary and testimonial record of Japan’s military expansion and “crimes against peace.”

At the same time, however, there was another side to the Tokyo-trial proceedings that did resonate, however obliquely, in the wake of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq—namely, the ricochet effect of the premise that individual leaders can be held responsible for conspiring to engage in aggression. Many U.S. military officers in Japan, like MacArthur’s intelligence chief Major General Charles Willoughby, privately opposed the Class A trials as “hypocrisy” and pointed out that the United States would have to make sure it won all its future wars. MacArthur himself was not so categorical, but also opposed the general indictment of Japan’s leaders for “responsibility for war” and confidentially confided that he would have preferred a short trial focusing on the Pearl Harbor attack. In the Iraq invasion, as with the Vietnam War earlier, these broad charges that the American-led prosecution promoted so vigorously in Tokyo—conspiracy, aggression, holding individual leaders to account for unprovoked wars of choice—came home to Washington. So did other postwar trials of the Germans and Japanese that involved atrocities and conventional war crimes like the abuse of prisoners.59

104. The trial of Saddam Hussein and a small number of codefendants, conducted by the Iraqi Interim Government beginning in October 2005, ended in Saddam’s execution on December 30, 2006. Proceedings focused on a few charges, most notably a massacre that took place in 1982. By contrast to the elaborate postwar trials of German and Japanese leaders, Saddam’s trial was exceedingly modest in both setting and substance. It neither set nor confirmed high standards in jurisprudence, nor did it make the slightest pretense at establishing a thoroughgoing record of the dictator’s deeds.

APART FROM THE showcase Class A trials, and long consigned to the black hole of memory, well over five thousand other Japanese officers and enlisted men were prosecuted for war crimes in “Class B” and “Class C” military tribunals conducted by the Allied victors in scores of locales throughout Asia. (The British, French, Dutch, and Americans all held such local trials in their restored or former colonial possessions.) Although Class C trials involved a relatively small number of high-ranking officers charged with responsibility for atrocities committed by troops under their command, they left an enduring mark on postwar military law. This derived primarily from the earliest and most famous of these military commissions, convened by the Americans in Manila and ending in the conviction of General Tomoyuki Yamashita. Yamashita was charged with having “unlawfully disregarded and failed to discharge his duty as commander to control the operations of the members of his command, permitting them to commit brutal atrocities and other high crimes against people of the United States and its allies and dependencies, particularly the Philippines.” He was found guilty on December 7, 1945, and sentenced to death—the month and day could hardly have been serendipitous—and both General MacArthur and the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the correctness of the Manila proceedings, the latter by a majority rather than unanimous vote.60

Yamashita, who earned the sobriquet “Tiger of Malaya” after leading Japanese forces to victory against a numerically superior British force in Singapore in the opening months of the war, had been assigned command of the beleaguered Japanese military in the Philippines in early October 1944, only weeks before the Americans launched their offensive to retake the islands. The atrocities perpetuated against Filipino “guerrillas” and civilians between then and June 1945—the period covered in the Manila trial—were indisputably appalling. Some 25,000 civilians were slaughtered in Batangas province; 8,000 in Laguna province; and another 8,000 men, women, and children in Manila. More disputable, and the focus of the military trial, was Yamashita’s responsibility for these crimes, which he claimed to have neither sanctioned nor even known about—a defense that prosecutors challenged with an indictment covering 123 particular charges. The prosecution argued, among other things, that while he was not personally present where the bulk of atrocities took place, Yamashita’s communications with Manila remained intact until June 1945; that he personally endorsed the summary execution of some two thousand “guerrillas”; and that he actually resided for a period in close proximity to some of the notorious camps holding Allied POWs.

None of the five U.S. officers who comprised the military commission that sat in judgment in Manila was a lawyer, and legal critics argue that this “lay court” produced a misleading and “ill-worded opinion” that required clarification in subsequent war-crimes trials conducted by the Allied powers. Still, the judgment in the Yamashita trial was reasonably clear in summation. “The Commission concludes,” it read, “(1) that a series of atrocities and other high crimes have been committed by members of the Japanese armed forces under your command against people of the United States, their allies and dependencies throughout the Philippine Islands; that they were not sporadic in nature but in many cases were methodically supervised by Japanese officers and noncommissioned officers; (2) that during the period in question you failed to provide effective control of your troops as was required by the circumstances.” Where later critics found this opinion wanting was its failure to make explicit that there was ample evidence that, contrary to his defense, Yamashita had knowledge of the high crimes that took place during his many months as military governor of the Philippines as well as commander of Japanese forces there.61

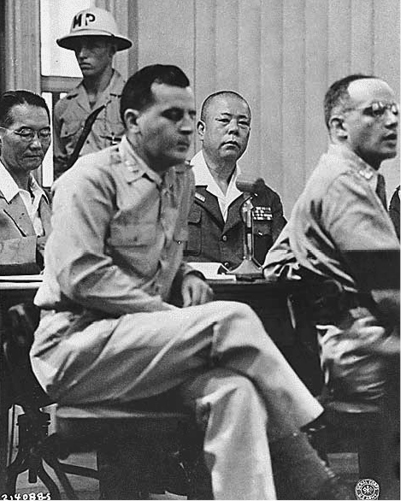

105. General Tomoyuki Yamashita, with his American defense attorneys, at the Manila military tribunal where he was found guilty of responsibility for atrocities committed by troops under his command. Yamashita was executed on February 23, 1946.

Although the charge of “command responsibility” was not unprecedented, it was rare in war-related legal practice until this time, making the “Yamashita precedent” noteworthy as a template for subsequent war-crimes proceedings against accused German as well as Japanese officers. In the Tokyo war-crimes trials, which did not get underway until four months after Yamashita’s execution, “count 54” in the prosecution’s indictment involved having “ordered, authorized, and permitted” conventional war crimes, while “count 55” picked up the Yamashita indictment of “deliberately and recklessly” disregarding “their legal duty to take adequate steps to secure the observance and prevent breaches” of the recognized laws and customs of war. Five “Class A” Japanese defendants were found guilty of the former count, and seven of the latter.62

Whatever the shortcomings of the loosely crafted Manila opinion, the “Yamashita precedent” became postwar shorthand for the basic legal principle of command responsibility. This received renewed media attention after the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and the incarceration without trial or redress of “unlawful enemy combatants” following 9-11, and vastly greater attention after the exposure of abuses in Abu Ghraib prison was accompanied by accusations (and, subsequently, clear documentation) that responsibility extended all the way up the line of command to the White House, Justice Department, Pentagon, and Central Intelligence Agency. The Yamashita case also calls attention to some of the same provisions in the 1907 Hague Regulations that are pertinent to legal debates concerning the occupations of Japan in 1945 and Iraq in 2003—for as military governor of the Japan-occupied Philippines, Yamashita was found derelict and criminally negligent in having failed to maintain public order and safety in the territory over which his authority as occupant extended. Abuses that took place under his command also violated the Geneva Conventions pertaining to prisoners of war.63

THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS pertinent when the war in Asia ended dated from 1929. The Japanese government had signed these provisions at the time, but in 1934—under the influence of the military establishment—the Japanese parliament refused to ratify them. Humane and solicitous treatment of prisoners, the argument went, was at variance with the military codes and discipline the Imperial Army and Navy imposed on their own fighting men where the disgrace of capture or surrender was concerned. Japanese officials subsequently offered assurance that, although not formally bound by the 1929 convention, the government “would apply it, mutatis mutandis, to all American, Australian, British, Canadian and New Zealand prisoners of war”—but this was mere verbiage. In the eyes of Japan’s Caucasian antagonists, nothing was more revealing of the barbarity of the Japanese than their abuse of Anglo POWs—and, framed legally, nothing made this clearer than their disdain for the spirit as well as letter of the Geneva provisions governing humane treatment of prisoners.64

The most extensive and least remembered postwar trials of Japanese addressed conventional (Class B) war crimes, and a large percentage of these cases involved abuse of Caucasian prisoners. All told, the total number of individuals indicted for B and C crimes combined was around 5,700, of whom an estimated 920 were executed (including a number of Korean and Formosan prison guards). It is indisputable that the Japanese military behaved atrociously and that POWs in certain camps were treated abominably. It is also clear that many of these local trials were hasty and arbitrary. Low-level prison guards were convicted, while their higher-ups escaped; defendants faced hearings conducted in languages other than Japanese; as in all military trials, evidence was admitted that would not be acceptable in civilian courts. On the other hand, just as in the Tokyo tribunal and lower-level command-responsibility trials, defendants were provided counsel. Unlike in the Class A trials or Yamashita case, moreover, a number of convictions were overturned on appeal.

Miscarriages of justice occurred, just as with individuals arrested as terrorists or “unlawful enemy combatants” in the wake of September 11—but the stronger impression that still comes through from the B and C trials is the gruesomeness of Japanese atrocities and the dehumanization that did take place in the war theaters, occupied areas, and prison camps. These were war crimes plain and simple, and as appalling to contemplate as the atrocities perpetuated by Al Qaeda and other terrorists, as well as in the insurgency, religious violence, and plain thuggery that took place in post-invasion Iraq and Afghanistan.

As so often, however, there is another side to this. After it became unmistakably clear how the Bush administration was actually treating prisoners under the euphemisms of “unlawful enemy combatants,” “enhanced interrogation,” “rendition,” and the like, the U.S. and Allied prosecution of Japanese crimes against POWs in particular took on a haunting, sometimes taunting aspect. Once again, current events drew attention to Japan’s wartime past. Again—as with the boomerang of “Pearl Harbor” as code for a war of choice—this cast unwelcome light on the conduct of the war on terror and the American practice, more generally, of double standards.

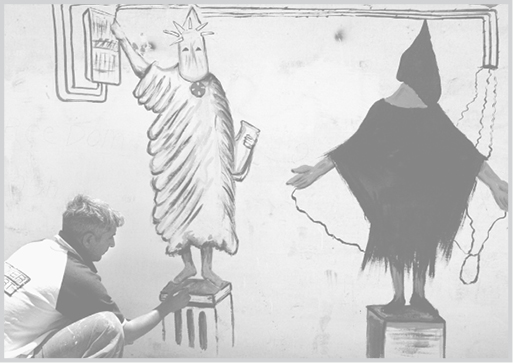

106. The release of photographs of U.S. torture at Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib prison in the spring of 2004 prompted this wall painting by the Iraqi artist Salah Edine Sallat. His hooded Statue of Liberty with her hand on an electrical switchbox stands alongside the most famous of the torture images, of a hooded prisoner connected to electric wires.

There are obvious differences: Japanese atrocities took place overall on a greater scale, and many prisoners abused and killed by the Japanese were not regarded as potential sources of critical information. But torture and other inhumane treatment of prisoners then, unlike later when it became Americans and their supporters flagrantly engaged in such acts, were called by their names and denounced unequivocally. “Water torture” aimed at obtaining information was one of these practices, and a very small number of Japanese were indicted and convicted for this. The moral outrage provoked by brutal treatment of prisoners was much more general in nature, however, as conveyed in Truman’s statement after Hiroshima and Nagasaki that the atomic bombs were used “against those who have starved and beaten and executed American prisoners of war.” This, it was argued at the time, was integral to what distinguished civilized people from barbarians, and the democratic nations from their Axis adversaries.65

SOME FORTY-FIVE YEARS after the World War II war-crimes trials ended, the Dutch jurist B. V. A. Röling, who sat on the bench in Tokyo as its youngest and perhaps most thoughtful member, acknowledged that “it is true that both trials [in Nuremberg and Tokyo] had sinister origins; that they were misused for political purposes; and that they were somewhat unfair. But they also made a very constructive contribution to the outlawing of war and the world is badly in need of a fundamental change in the political and legal position of war in international relations.” The Tokyo trial was thus “a kind of milestone in legal development, and the attitude on which the judgments were based is absolutely necessary in an atomic age.”66

107. An Iranian couple walks past giant murals on a highway near Tehran reproducing two of the most notorious Abu Ghraib torture photographs. The Persian script reads, “Today Iraq.”

Much the same attitude was reflected in the emphasis on command responsibility highlighted by the Yamashita trial and refined in a small number of subsequent trials of German and Japanese officers. A lengthy analysis published in the U.S. Army’s Military Law Review in 1973 thus closes with the summary observation that “out of the ashes of World War II there rose a desire to further define the responsibility of a commander for war crimes committed by his subordinates, a responsibility recognized by the earliest military scholars.” The principle is complex, as this detailed analysis demonstrates—but also severe and exacting where “wanton, immoral disregard” of the acts of subordinates is demonstrable. Military law makes clear that a nation’s leaders must be held to the highest standards of duty and responsibility; and where this is wanting and reckless acquiescence in such behavior prevails, “criminal responsibility” must be attached to such disregard.67

The 1973 study was published after the My Lai massacre in Vietnam drew renewed attention to the issue of command responsibility. (My Lai involved the mass murder of hundreds of South Vietnamese civilians by U.S. troops in 1968, and provoked worldwide outrage when exposed in 1969.) Viewed in retrospect, this judicious analysis by a military lawyer stands chronologically roughly halfway between General Willoughby’s whispered criticism of the war-crimes trials of Japanese and the war on terror that followed September 11; and it resonates with both.

Willoughby warned that the United States had to make sure it won all its future wars, which it failed to do in Vietnam and again in Iraq. “My Lai” became a graphic metaphor or trope for infamous, criminal behavior in the Vietnam War—much as “Nanking,” “Pearl Harbor,” and “Bataan” or “our prisoners of war” did vis-à-vis the Japanese in the earlier war, and “Guantánamo,” “Abu Ghraib,” and “waterboarding” did vis-à-vis U.S. war conduct after 9-11. When Willoughby called attention to Allied “hypocrisy,” he was able to keep such heretical thoughts private. Such controls began to disappear in the 1960s and 1970s, when television reportage came of age, and by the twenty-first century had been almost completely blown away by the revolution in cyber-communication—and, as the conservative critics would emphasize, by the rising influence of international law and the human-rights and civil-rights movements.

Despite the revolution in communications, however, and despite “lawfare” and the legions of lawyers the military and federal bureaucracy have enlisted to address this, it is still sobering to observe how much did not change between the 1970s and the war on terror. For all practical purposes, the legal precedents and principles the United States itself promoted after World War II were repudiated almost as soon as the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials wound down. It was acceptable that the United States and its allies sit in judgment of others, naïve to expect them to hold themselves to the same standards, and inconceivable that Americans would ever allow themselves to be called legally to account by non-Americans. Even putting aside larger questions concerning just war (jus ad bellum) and just practice in war (jus in bello), there was no serious command responsibility for conventional atrocities in Vietnam—or in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Unaccountability consistently trumped “lawfare”—to the point where “international fora” and “judicial processes” could be officially aligned with “terrorism” as simply additional weapons of the weak.

Spheres of Influence and the Limbo of Defeated Armies

Both the dubious legality of root-and-branch reform in occupied Japan and the convoluted legacies of the Japanese war-crimes trials are neglected in most accounts, since so much else in the way of constructive accomplishments was taking place in that defeated and isolated nation. Also neglected is the degree to which Allied victory and the putative end of a horrendous global conflagration was followed, almost seamlessly, by betrayals of wartime promises, insurrections, and new conflicts and crimes throughout Asia.

In theory, Japan’s defeat liberated hundreds of millions of Asians who had been invaded, occupied, and oppressed by the emperor’s men. In actuality, it paved the way for wars and occupations that involved the Allied victors themselves—and that hold a murky mirror, in their own way, to the invasion of Iraq and aspects of that later tragedy that are less unique than often claimed. Here the mirror reflects not only promises of liberation that were betrayed with terrible consequences, but also other persistent cultures of war as well: myopic “realism”; abuse of surrendered forces, and the legal contrivances that may abet this; lawlessness, terror, insurrection, and nationalisms capable of paralyzing materially superior military forces.

In his “message to the American people” delivered on September 2, 1945, MacArthur had declared that “today the guns are silent. . . . Men everywhere walk upright in the sunlight. The entire world lies quietly at peace.”68 For millions of war survivors in Asia, as in Europe, this was fiction: false light rather than sunlight, a fleeting lull at best. Suffering did not end for them, just as it did not end for the people of Iraq after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein; and much of this suffering involved callousness on the part of the victors. In place after place, country after country, men who did now walk tall in the sunlight often did not hesitate to hold others down, be they surrendered Japanese or Japan’s former Asian victims. For those consigned to this fate, it was cruel to speak of the world lying quietly at peace—much as, in comparable ways, it was bitter for Iraqis decades later to have to listen to the American invaders constantly speaking about “liberation” and how they should be grateful to the United States as their country fell under foreign control and their personal lives became caught in a vortex of violence.

Japan’s militaristic rise and fall rang the knell for old-style colonialism in Asia. The death throes were protracted, however, and the disconnect between rhetoric and reality remained little changed after MacArthur declared that the world at last lay quietly at peace. In 1941 and early 1942, Japan had usurped the place of the British, French, Dutch, and U.S. colonial powers in Southeast Asia and the Philippines in the name of “coexistence and coprosperity,” proclaiming the dawn of a new era in which Great Nippon would serve as “the Leader of Asia . . . the Protector of Asia . . . the Light of Asia.”69 Many natives in this vast “southern region,” extending across an area of over a million square miles, initially embraced these proclaimed anti-imperialist goals. They observed the rout of the Western colonial powers with astonishment, and in many instances welcomed the emperor’s men as liberators; but the embrace rarely lasted. Economic exploitation and political oppression eclipsed initial hopes and promises, and outside the ranks of close collaborators no one mourned Japan’s demise.

The American and British counter-proclamation of a new dawn for Asia and, indeed, the world was articulated early on in the “Atlantic Charter” jointly issued by Roosevelt and Churchill on August 14, 1941. This pledged, among other things, to “respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live.” Although issued before Pearl Harbor and U.S. entry into the war, with Germany’s aggression uppermost in mind, these ideals were reaffirmed in a “Declaration by the United Nations” (at that date, the term referred to the Allied powers) issued on January 1, 1942, in the name of twenty-six anti-Axis nations. Signatories included the four governments that would assume responsibility for overseeing Japanese military surrenders in the field throughout Asia: the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and China. The declaration began by citing the Atlantic Charter, and then rephrased this as a conviction “that complete victory over their enemies is essential to defend life, liberty, independence and religious freedom, and to preserve human rights and justice in their own lands as well as in other lands.” It was for this reason that they were “now engaged in a common struggle against savage and brutal forces seeking to subjugate the world.”

Nationalists throughout Asia took such declarations seriously as a promise that a victorious United States would take the lead in promoting a postcolonial world. From the moment Japan surrendered, these hopes and expectations were expressed with an intensity that caught Washington and London (and Paris and The Hague as well) by surprise. The phrasemakers obviously had not really paid much mind to their real-world audiences in distant and culturally alien lands. A British officer in the first contingent of U.K. troops that arrived to take the Japanese surrender in Java in September 1945, for example, later wrote with some wonder about the fervor for independence that greeted them. All around, when they entered Batavia, they beheld “huge slogans daubed in sprawling characters on the sides of vehicles and carriages. ‘Atlantic Charter means freedom from Dutch Imperialism,’ shouted one. ‘America for the Americans—Monroe. Indonesia for the Indonesians,’ screamed another. Everywhere the signs of rampant nationalism abounded. A caller lifting up a telephone receiver would be greeted by a bark of ‘Merdeka’ (Freedom) from the exchange.”70

Some former colonies of the Western powers did gain independence soon after Japan’s defeat, the Philippines and India notable among them. For millions of Asian nationalists elsewhere, however, wartime rhetoric about self-determination had little more substance than Japan’s posturing as the Protector and Light of Asia. Throughout the length and breadth of Japan’s crumbling empire, moreover, the assignment of responsibility for taking military surrenders in the field amounted to confirmation of Allied spheres of influence: the Soviet Union in Manchuria and half of Korea; Chiang Kai-shek’s corrupt Nationalist regime throughout China, thoroughly dependent on U.S. military support; the United States in the Philippines, Japan, southern half of Korea, and entire Pacific Ocean area (newly christened an “American Lake” by some U.S. planners and pundits at the time); and the United Kingdom in Southeast Asia, where it was understood the British would reestablish their former territorial domination while also paving the way for the return of French and Dutch colonial authority. When forces led by the United Kingdom followed Japan’s formal surrender in Tokyo Bay with their own ceremony in Singapore on September 12, accepting the surrender of all Japanese troops in Southeast Asia, the massed bands of the fleet captured the hubris of the moment with a spirited rendering of “Rule, Britannia!”71

108. Allied POWs liberated at Japan’s Aomori prison wave U.S., British, and Dutch flags, August 29, 1945.

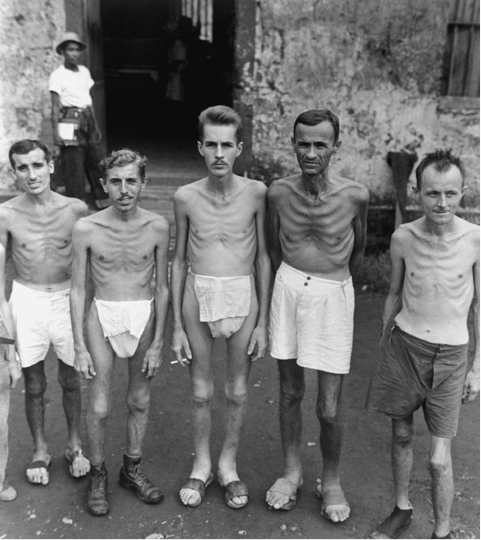

109. Emaciated American POWs liberated at Manila’s Bilibid prison, February 1945.

110. Japanese POWs in Guam listen to the emperor’s announcement of Japan’s capitulation. Over six million Japanese awaited repatriation from overseas at war’s end, and the return of scores of thousands was delayed for months and even a year or more.

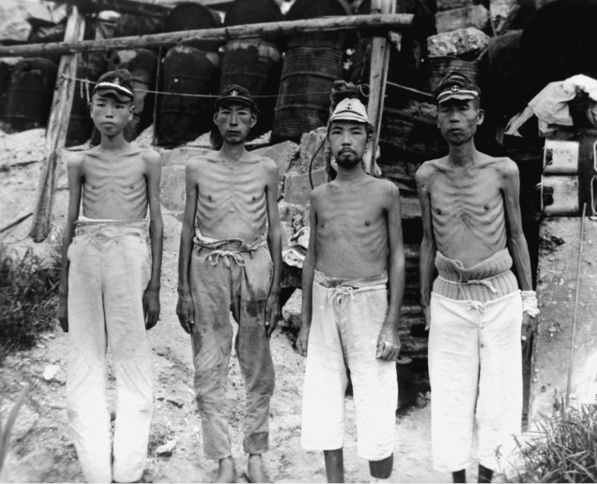

111. Starving Japanese sailors rescued from the Marshall Islands after being stranded by the U.S. island-hopping campaign, September 1945. Much of the strong antimilitary sentiment in postwar Japan derived from the suffering that both military personnel and civilians experienced once the war turned against them.

Much of this division of labor and influence was practical. Some of it was accompanied by intense debates concerning if, when, and how old-style Western imperialism and colonialism could be eliminated or at least gradually phased out (through some sort of international trusteeship, for example, or pledges of eventual independence). The entire grand undertaking of moving from war to a hoped-for peace—a more intractable challenge than driving the great war machines forward had been—was undercut at almost every step by sharp disagreements among the erstwhile American, British, French, and Dutch allies.

The upshot of such complexity and contention, in any case, was fairly simple. Power politics governed postwar policy—and, just as had been the case in the war itself, Europe and the West took priority over Asia in U.S. planning. Why, despite strong public and private condemnations of the evils of the old imperialist system that Japan had uprooted, did U.S. policy makers ultimately extend political and material support to the British, French, and Dutch reoccupation of Southeast Asia? Secretary of State Cordell Hull minced few words about this. “We could not alienate them in the Orient,” he explained in his memoirs, “and expect to work with them in Europe.”72

This Europe-centrism was compounded by the fact that the vast majority of Allied military and civilian planners, both in the capital cities and in the field, had no prior knowledge of the atomic bomb and were caught by surprise by Japan’s sudden surrender. Preoccupation with war strategy far outweighed intelligence gathering and planning for postwar challenges, and almost no one anticipated how formidable nationalistic and revolutionary agitation would prove to be everywhere from Korea through China to Southeast Asia. What in retrospect should have been predictable was not predicted—neither for the first time nor for the last.

The role played by Japan and many Japanese in this immediate postwar confusion and chaos was ironic. The defeated nation itself, instigator of so much death and destruction, was cocooned by the occupation and isolated from this violence and, indeed, from the world at large. Huge numbers of surrendered Japanese overseas, on the other hand, became an unwitting part of the upheavals that now convulsed the continent. Some military units were ordered to retain their weapons and participate actively in maintaining local “law and order,” while other fighting men and technical personnel joined, or were coerced into joining, indigenous nationalist and communist movements. Scores of thousands of the emperor’s loyal men thus found themselves engaged in new wars side by side with yesterday’s adversaries. Hundreds of thousands who were spared this fate, moreover, still found themselves in a limbo of a different sort, as the victors delayed their evacuation and used them as forced labor. Protections conventionally guaranteed prisoners under the laws of war were withdrawn—extensively, arbitrarily, and with little public notice or outcry.

CLOSE TO 6.5 million Japanese fighting men and civilians awaited repatriation from overseas after August 1945, while slightly less than 1.2 million non-Japanese—mostly Koreans—desired repatriation from Japan to their native lands. The logistics were daunting, the process was complex and protracted, and in most cases the speed of return was impressive.

MacArthur’s headquarters in Tokyo, which organized the shipping and domestic processing involved, took pride in its handling of these huge numbers. Roughly 1.5 million Japanese had been returned to the home islands by the end of February 1946, and another 1.6 million followed between March and mid-July. By the end of 1946, SCAP placed the total number repatriated back to Japan at 5.1 million. Before as well as after December 1946, however, it is difficult to trace the exact disposition of large numbers of military personnel and civilians. The Soviet Union engaged in the most notorious and prolonged abuse of surrendered Japanese, but was not alone in delaying the return of many whose only crime was being on the losing side.73

Although the Soviet Union did not enter the war against Japan until its final week, the number of Japanese troops and civilians that fell under its nominal control in Manchuria and northern Korea was huge, possibly in the neighborhood of 1.6 million. Some 293,000 managed to make their own way from northern Korea to the south, and around 625,000 others were repatriated by the Soviets by the end of 1947. The Japanese government calculated that as many as 700,000 were transferred to Siberia and interned as laborers. Although the Soviet Union resumed repatriation in May 1948, by the spring of 1949 Japanese and U.S. officials put the number still detained at over 400,000 and possibly as high as 469,000. They were shocked when the Russians claimed only 95,000 remained.

The last Japanese did not return from Siberia until the early 1950s; and it was not until 1991, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, that Russian records were released giving the names of some 46,000 Japanese who perished in Soviet hands. The precise numbers interned, and deceased, remain uncertain. Those detained the longest in the Soviet Union also were subjected to intense communist and anti-American indoctrination, and some of this was manifested in strident behavior by returning repatriates beginning in 1948. Postwar murder, abuse, and indoctrination by the Russians took place on a much greater scale where captured Germans were concerned; and all this naturally fed the Cold War propaganda machine in as well as outside Japan, where it was offered as one more confirmation of the brutal nature of the Soviet regime.74

IN CHINA, WHICH unlike the Soviet Union had suffered grievously at the hands of the Japanese, mass repatriation generally moved as quickly as could be expected—but with exceptions that were noteworthy in almost counterintuitive ways. For the duration of the long war that followed Japan’s invasion in 1937, China was also at war with itself: an unoccupied interior counterpoised against a vast seaboard administered by collaborators under Japanese control, and a pent-up civil war pitting the Guomindang or Nationalists against Communists that was only superficially suppressed in the name of presenting a united front against Japanese aggression.

With Japan’s capitulation, the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek enlisted U.S. military support to extend their authority nationwide. In fighting this reignited civil war, they not only delayed the evacuation of thousands of skilled Japanese technicians (and their dependents) but also enlisted the support of armed Japanese, particularly in the north where the Communists were strongest. Scores of thousands of Japanese troops remained active under Nationalist command for well over a year after the surrender—in some cases up to the time of the Communist victory in 1949.75

Because these uses and abuses of Japanese troops and technicians were embarrassing for all parties concerned, they received grudging acknowledgment at best. Much of what we rely on to reconstruct what took place thus remains disjointed and anecdotal. In November 1946, fifteen months after the surrender, for example, U.S. General Albert Wedemeyer complained about the slowness of the Nationalists in disarming the Japanese and concluded there were upwards of seventy thousand such troops in and around Beijing. At the very end of January 1947, a seasoned American diplomat in Nanjing calculated that around eighty thousand fully equipped Japanese troops were operating under Chiang’s command in Manchuria. One of Chiang’s closest collaborators in these activities was General Yasuji Okamura, the Japanese commander in chief in China when the war ended. In 1942 and 1943, Okamura had carried out a notorious “kill all, burn all, loot all” scorched-earth offensive against the Communists and their peasant supporters in north China that, by some accounts, killed over two million civilians. Okamura remained in China until 1949 as an adviser to Chiang, who protected him from indictment for war crimes. The Nationalist government also delayed the repatriation of thousands of Japanese administrators and technicians in Japan’s former colony Formosa (Taiwan).76

Chiang’s government was not the only force in China that both cultivated Japanese officers and exploited Japanese fighting men after the surrender. Some fifteen thousand Japanese troops, including officers, were commandeered to serve under the warlord Yan Xishan (Yen Hsi-shan) in Shanxi province in his doomed struggles against the Communists, with somewhere around seven thousand perishing by the time Yan was militarily crushed in 1949. (Their Japanese general, Hosaku Imamura, committed suicide when Yan capitulated.) The Chinese Communists, on their part, also both enticed and coerced many thousands of Japanese soldiers and technicians into joining their side in the civil war—with the result that on a number of occasions “post surrender” Japanese pawns found themselves fighting each other in China’s internecine bloodbath. The numbers concerning surrendered Japanese and delayed evacuation from China are as slippery as for the Soviet Union, but in April 1949, with Chiang and his tattered forces having fled to Taiwan and the Communists poised to declare the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, U.S. intelligence estimated that upwards of sixty thousand Japanese still remained in Manchuria.77

IN SOUTHEAST ASIA, responsibility for taking the Japanese military surrender was delegated to the U.K.-led Southeast Asia Command (SEAC) under Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. Mountbatten’s instructions, received before Emperor Hirohito actually broadcast Japan’s capitulation, made London’s priorities clear: reoccupation of Burma, Singapore, and major parts of Malaya; then Hong Kong, followed by “French Indo-China,” where SEAC would prepare the way for the return of “French forces and civil affairs personnel”; then Siam (Thailand); and finally Java and Sumatra, where the mission was “to accept the surrender of Japanese forces and to prepare for the eventual handing over of this country to the Dutch civil authorities.”

In forcing their return, the British, French, and Dutch received largely unpublicized political, economic, and material support from the United States—and military support from the newly baptized “JSP,” or Japanese Surrendered Personnel. The JSP, as it happened, were not the only Asian military who were enlisted to help suppress local independence movements. Most of the troops in Mountbatten’s SEAC, and most of the casualties that command sustained, came from India.78

With the support of their about-to-be-deposed Japanese overlords, indigenous forces led by Sukarno declared Indonesia’s independence on August 17, while Vietminh forces under Ho Chi Minh in Indochina, having established what appeared to be firm control in both the north and the south, declared an independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam on September 2. These nationalist movements posed formidable challenges to reestablishing European colonial control—and, where Indonesia in particular was concerned, left the British, Americans, and Dutch momentarily thunderstruck. The latter, speaking largely through their colonial officials in exile (mostly in Australia), had assured everyone that their return would be welcomed; and both Mountbatten’s SEAC and planners in Washington took such assurances at face value.

A State Department memorandum shortly after the surrender, for example, paraphrased the Dutch commander in chief of the Netherlands Indies Army as reporting earlier “that the people of the NEI [Netherlands East Indies] except for a few dissidents would generally support the former NEI Government and that it was the general impression that Japanese propaganda in the NEI had influenced about one tenth of 1% of the population.” In June 1945, the State Department itself finalized a major report predicting that “the great mass of the natives will welcome the expulsion of the Japanese and the return of the Dutch to control.”

As the official British military history of these developments put it—in language that easily can be transposed to criticisms directed against the Bush administration’s wishful thinking about Iraq almost sixty years later—it quickly became “quite clear that the situation as described to Mountbatten when he was made responsible for the whole of the Netherlands East Indies had been a supreme example of wishful thinking. Instead of willing co-operation by the Indonesians, there was not only an open threat of war but also a considerable Indonesian force trained and equipped by the Japanese and ready to fight anyone attempting to restore Dutch dominion.”79

Despite Japan’s hasty support for Sukarno’s declaration of independence on August 17, and despite the provision of weapons and supplies to the nationalists and desertion of some Japanese soldiers to their side, the bulk of Japanese forces dutifully complied with SEAC’s orders. And despite Allied denunciations of the “inhuman, bestial practices” (Mountbatten’s words) of the Japanese vis-à-vis their prisoners that the victors were discovering in many different locales, this did not prevent SEAC from ordering the defeated enemy to remain armed and to enforce “law and order” against the native nationalists until Dutch forces arrived and proved capable of taking over.

Some but not all of this was police work. In an eloquent “Christmas Day” letter submitted to President Truman in the closing days of 1945, the prime minister of the contested Republic of Indonesia wrote of air and naval bombardment by the British and went on to note that “the British and the Japanese acting under British orders have put many of our villages to the torch as punitive measures. Surabaya and Semarang are almost in ruins in consequence of the fighting that has taken place there.” He then proceeded to invoke the particular faith that Asian nationalists placed in the United States as the last hope for defending the Atlantic Charter ideals: “We look to you, as the head of a country that has always been in the forefront of the fight for liberty, justice and self-determination, to use the benefit of your influence to stop the present bloodshed in Indonesia.”80

An incisive essay on the SEAC policy of “sleeping with the enemy” puts the number of surrendered Japanese used militarily by the British and Dutch at upwards of 10,000 in Java, and “24,000 crack Japanese troops” (in the May 1946 words of the British Foreign Office) in Sumatra, with the total number of Japanese casualties placed at 717 dead, 387 wounded, and 205 missing in action. The United States followed these developments closely, especially in Sumatra where the primary objective was to defend oil refineries in which the Americans as well as Dutch and British had substantial vested interests. When Dutch forces finally arrived in sufficient force in mid-1946, the British transferred 13,500 surrendered Japanese to them, most of whom were not repatriated until May 1947.81

THE INDONESIAN STRUGGLE for independence continued until late 1949, when the Dutch finally abandoned their dream of a restored empire. (This was a hard dream to let go, since they had been ensconced in the East Indies since the seventeenth century.) In Indochina, the Allied betrayal was more tragic. Under the surrender arrangements agreed upon by the “Big Four” Allied powers at Potsdam in July, the Chinese Nationalists were responsible for taking the Japanese surrender in the northern half of Indochina, with SEAC taking charge in the south. The Chinese eventually acknowledged the sovereignty of the newly declared Republic of Vietnam, while the British, with U.S. support, did not. In facilitating the return of the French to the south, London and Washington ensured civil war and pursued a policy that eventually culminated in the Vietnam War. After the collaborationist disgrace of the wartime Vichy regime, France moved quickly to become, once again, occupier rather than occupied and (as a State Department report predicted even before Japan’s surrender) to “reassert her prestige in the world as a great power.” SEAC turned control over to French authorities in Saigon on December 19, 1945. Until then, however, much of the initial responsibility for maintaining law and order in the south was, again, delegated to the Japanese.82

British representatives did not arrive in Saigon until the last days of August, and upon surveying the scene they ordered the roughly seventy thousand Japanese military in the south to remain armed and garrisoned until SEAC and ultimately the French could take over. The Japanese performed critical logistics operations over the next few months. Their air force flew an estimated one hundred thousand miles under British orders, for example, carrying tens of thousands of pounds of supplies and ferrying some one thousand French and Indian troops. In mid-October, two months after the emperor announced Japan’s capitulation, Japanese forces assisted U.K. and French troops in securing Saigon and its environs.

It was not until mid-November that SEAC finally announced locally that the disarmament of Japanese forces in Vietnam “will now begin,” and not until the final days of November that the formal military surrender was completed and the British began to concentrate Japanese troops for repatriation and prepare for their own departure as sufficient French forces to take over arrived. Around the beginning of December, the Japanese calculated that they had suffered 406 casualties, including 126 killed, in fighting the Vietminh for their new masters.83

Article 6 of the Hague Regulations reads, “The State may utilize the labour of prisoners of war according to their rank and aptitude, officers excepted. The tasks shall not be excessive and shall have no connection with the operations of the war.” The laws of war clearly did not sanction the use of prisoners in new wars entered into by their captors—nor did these regulations and conventions permit using surrendered fighting men as laborers long after the original conflict had ended. Nor, of course, did they condone their neglectful treatment. In one form or another, all of the victors in Asia engaged in such transgressions.

Japanese who surrendered to Mountbatten’s SEAC were sometimes concentrated for extended periods in conditions that contributed to malnutrition and illness, for example, while scores of thousands who were physically fit were held back to perform labor tasks. When in mid-1946 MacArthur’s headquarters requested that all Japanese be repatriated by the end of that year, the British announced their intention to retain 113,500 beyond then. As it transpired, they kept over 80,000 JSP for labor in Malaya and Burma into 1947, with the last of them not being returned to Japan until the end of that year—over two years after the war ended.84

The Americans, on their part, made no bones about evacuating “sick and other ineffectives” or “unproductive laborers” as promptly as possible while retaining more able-bodied Japanese as workforces in areas under their military control (“maintenance and repair of essential installations” was one descriptive phrase). This included at least 69,000 prisoners whose return home was delayed until the last three months of 1946—fourteen to sixteen months after the surrender (45,000 in the Philippines, 12,000 or more in Okinawa, 7,000 in the Pacific Ocean Area, and 5,000 in Hawaii). Masaki Kobayashi, who later became one of postwar Japan’s most distinguished film directors, admired for his uncompromising depictions of war and oppression, was among the surrendered soldiers detained to labor in Okinawa until the end of 1946.85

Legalistic and euphemistic manipulations abetted these uses and abuses of surrendered enemy. Before the Allied victory over Germany was consummated, the British government introduced a legal turn of phrase to categorize German military taken prisoner under the unconditional surrender in a way that would remove them from the protection of international law. They were identified as “surrendered enemy persons” or “disarmed enemy persons”—and, as such, consigned to a status that presumably was not covered by the Hague and Geneva provisions, thus allowing them to be exploited as laborers and deprived of other rights and protections such as a guaranteed level of daily nutrition. Much the same linguistic subterfuge—“disarmed military personnel,” “Japanese Surrendered Personnel”—was employed to similar ends in Asia. Seen in the light of such earlier maneuvering around humane laws and conventions, the Bush administration’s later constructions of “unlawful enemy combatants” and the like, together with the abuse of captured individuals this facilitated, seem less exceptional than critics often claim them to be.86

WHILE THE FORMER victims and enemies of the Axis powers were largely indifferent to the fate of surrendered troops, in Southeast Asia the betrayal of promises of liberation was shocking and ultimately tragic. Britain’s unflagging imperial ardor was apparent for all to see. (In more Anglophobe U.S. circles, SEAC was said to stand for “Save England’s Asian Colonies.”) So was the colonial or neocolonial fervor of France and the Netherlands, whose return to Southeast Asia was openly supported by SEAC. The United States was more disingenuous—proclaiming its commitment to the ultimate goal of “self-government” even as it transported French forces from Marseilles to Saigon and urged the Dutch to remove the “U.S.A.” Lend-Lease insignia from the military vehicles and weapons they relied on in reoccupying Indonesia. Without political and material U.S. support, the colonial reoccupations in Southeast Asia would have been impossible.87

As would happen repeatedly in later years and decades, the Western powers undertook these attempts to forcefully impose their authority without appreciating the pride, hope, humiliation, and ultimately rage that lay behind the indigenous movements—and with scant self-reflection about how their white man’s arrogance was perceived. One of the few Westerners who did try to see Asia through Asian eyes was the American journalist Harold Isaacs, who witnessed these tumultuous developments and published his observations in a scathing 1947 book titled No Peace for Asia. In one vignette, Isaacs quoted a Dutch news release in Batavia titled “Collective Amok in Java,” based on an analysis by a Dutch doctor. Indonesians agitating for independence and self-determination, in this diagnosis, were suffering from a bad case of “wish-fulfillment as regards Eastern superiority,” and had been overcome by “a kind of dream life, a trance, a spiritual madness.” He had, the doctor declared—shades of Joseph Grew on the Japanese during World War II, and L. Paul Bremer on Iraqis after the invasion in 2003, and uncountable other Westerners in between—observed this dream life taking “the place of rationalism brought by Western education, yes, even in highly educated individuals.” “The hordes live in a mystic world of makebelieve,” the analysis continued, and “carry on right in front of machine guns and beneath thundering planes. Still, the military answer is the only answer available to these hordes of fanatics.”88

This is the imagined dichotomy between rational Westerners and irrational hordes of people of color that, for most Caucasians, never ceases to be gospel. When the commander in chief of the Dutch colonial forces had a moderately cordial conversation with nationalist leaders, for example, he reported with some surprise that “native delegates showed understanding and common sense.” A few days earlier, his political adviser had informed the U.S. consul in Batavia (as cabled to Washington) that the “Indos” were “living in dream world of their making in which realistic arguments and actual facts are nearly excluded.” These, of course, were the same Western officials that historians look back on as living in untenable dream worlds of their own; and those on the receiving end of such condescension were aware of this from the start.

An Islamic scholar responding to the “Collective Amok in Java” report, for example, politely observed that “it is the Dutch who are much more seriously afflicted with the hysteria of which this doctor writes.” Apart from rare exceptions like Isaacs, the Westerners themselves were rarely capable of such irony, certainly not if it involved self-perception. Thus, hard-nosed negotiating of the sort the Europeans and Americans themselves had perfected became underhanded when proud and assertive non-Westerners practiced it. When the moderate president of the newly proclaimed Republic of Indonesia stated he would deal with a Dutch official as an envoy of a foreign government rather than colonial authority, the U.S. acting secretary of state (Dean Acheson) dismissed this as “typical oriental bargaining.”89

ALTHOUGH IT IS natural and almost irresistible to compare and contrast occupied Iraq with occupied Japan, in many respects the attempt to reimpose Western hegemony in Southeast Asia after Japan’s defeat provides an equally telling analogy. Be that as it may, this panoramic spectacle of a vaster Asia being occupied and reoccupied and torn asunder by foreign intrusion and domestic upheaval casts what took place in occupied Japan in clearer light. Isaacs, for one, was not won over by the hosannas to demilitarization and democratization emanating from MacArthur’s headquarters in Tokyo immediately after the war. He dismissed the occupation as “a preposterous and macabre comedy,” and placed the defeated nation firmly in the context of planning for the next war. “Every correspondent in Tokyo,” he reported, “heard officers of general rank describe Japan as ‘the staging area for the next operation’ ” against Russia or—as he himself anticipated—a Communist China.90

To Asians everywhere (as to Isaacs himself), it looked “very much as if the Americans were ready to allow the hated Japanese more relative self-government, freedom, and independence, than they were willing to see granted to any of Japan’s recent victims”—be they Koreans or Annamites or Javanese, all of whom saw themselves as being at least as capable of running their own affairs as the Japanese. It was the Japanese, after all, who had plundered Asia and plunged it into the agony of war; and it was not other Asians “but the Americans, the British, the Japanese, the French, and the Dutch who had proved incapable of organizing any kind of secure peace in the Far East.” Yet despite all this, Japan was being allowed to retain “not only its national identity but the essence of its old regime, while in the colonies the efforts of subject peoples to achieve their national identities were uniformly frustrated.”

That the victorious powers did not hesitate to use Japanese troops in suppressing the nationalist movements, in Isaacs’s view, could only be seen as “a further shocking and cynical indignity. This was not quite the picture people had of what American victory over Japan would mean in Asia.” Almost overnight, the United States had dissipated “the greatest political asset ever enjoyed by any nation anywhere in our time”—the promise of being a true champion of the Atlantic Charter ideals. For Isaacs, who did not ignore the shortcomings of the independence movements, this could only be regarded as “one of the most extravagant and prodigal examples of conspicuous waste ever recorded in the annals of the nations.”91

Here, from yet another perspective, were more new evils in the world. In the great game of power politics, the occupation of Japan was but a piece in a larger agenda of “staging areas” and spheres of influence strategizing in Asia; the use of surrendered Japanese to maintain law and order became a telling, if unplanned, part of this game; and the paternalistic attentiveness directed toward the defeated Japanese emerged as a sharp contrast to U.S. and Allied policy and practice toward other Asians.

The only place in Asia where the guns were really stilled and peace prevailed was Japan.