NATION BUILDING AND

MARKET FUNDAMENTALISM

Apart from law and justice, there are other areas where rough similarities tell us something more complicated about wars and occupations than emerges in the usual perception of Japan and Iraq as antipodean examples of success and failure. Although there was little violence in occupied Japan, and none against the occupation forces, for example, crime and corruption were serious problems. Largely forgotten today, looting took place on a massive scale prior to the arrival of U.S. forces. The difference from the plunder and vandalism that followed Saddam Hussein’s fall was qualitative: in Japan, the looting was quasi-official, clandestine, and almost fastidious—the work of efficient thieves in the night who did not dream of sacking ministries and museums.

In a different direction, seemingly draconian policies that proved disastrous in Iraq—particularly the elimination of the military establishment and categorical purge of former officeholders—were also integral to the policy of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers. What differed was the outcome: in Japan, these policies caused personal distress, but not chaos. As in Iraq, too, many policies central to the early occupation agenda—like reparations and drastic economic deconcentration in Japan’s case—amounted to false starts. On the other hand, certain policies of lasting influence—most famously constitutional revision—came about as a result of essentially ad hoc initiatives on the part of MacArthur and his Tokyo headquarters, rather than careful planning in Washington.92

“Ad hoc” was the name of the game in Iraq, given the fact that prior planning for occupation and nation building was nil; and constitutional revision also became part of the reformist agenda hastily introduced by the Coalition Provisional Authority. For all the reasons that made defeated Japan a vastly different society than post-Saddam Iraq, however—social cohesion, a pervasive secular outlook, deep identity as a culture and country, and meaningful experience as a pluralistic civil society—“democracy” did not find the same solid constituency in Iraq.

Two of the most striking points of partial convergence in conduct of the occupations were simultaneously the most telling points of divergence. One was the usurpation of Japanese and later Iraqi sovereignty and imposition of near-absolute U.S. control. The second involved promoting capitalism. Taken together, these illuminate how greatly the American conduct of war and peace changed over the decades that followed World War II.

MacArthur exercised authority in Japan for almost six years (he was relieved of his command in April 1951), as opposed to Bremer and his traumatic “year in Iraq” (the title of his memoir). The differences, however, went far beyond this. MacArthur operated within a clear chain of command and exercised control over both security and civil affairs. Nonmilitary personnel helped staff his General Headquarters (GHQ) in Tokyo, but the sort of ideological litmus tests that took place in staffing the CPA in Iraq—where party affiliation and even religious convictions influenced recruitment—did not take place in the critical early years. On the contrary, eclecticism and bipartisanship gave GHQ much of its early vitality. (Bias against liberals and leftists entered the picture around 1947–48, with the intensification of the Cold War and introduction of the reverse course.) MacArthur welcomed civilian task forces to investigate matters requiring technical expertise, both before and after the reverse course, but legions of private contractors did not invade the defeated country alongside his victorious forces.

The post–1945 task forces reflected an old-fashioned sense of public duty on the part of the experts recruited that had all but disappeared by the twenty-first century. By much the same measure, the old military operated under a broader definition of responsibilities and obligations, which extended to engaging in civil affairs in occupied lands and taking care of the daily needs of its troops. In the process, it maintained the appearance and in large measure reality of not merely discipline and control, but also integrity and accountability. No one will ever associate discipline, control, integrity, or accountability with the occupation of Iraq, either during or after the short life of the CPA.

Just as in Iraq, creating a sound capitalist economy was always a goal in Japan. What was understood as “capitalism” (and “sound” as well) was another matter entirely. Land reform, encouragement of organized labor, and trust busting were central to SCAP’s early reforms aimed at “economic democratization.” Even after projections for Japan changed with the Cold War, moreover, it was taken for granted that the state had to play a major role in promoting economic development. This meant not only the U.S. state as the occupying power, but the Japanese state as an essential player in establishing and enforcing economic priorities and, where deemed necessary, protecting vulnerable industries and enterprises against foreign exploitation.

By contrast, once the Americans found themselves plunged willy-nilly into reconstructing Iraq, they pursued this with a zealotry that reflected the reigning dogmas of market fundamentalism. “Privatization” became the catechism of these latecomers to nation building. At one critical early point, much of occupied Iraq’s economy appeared to have been put up for sale. At every point, an immense portion of the tasks and functions involved in planning and directing civil affairs in a shattered nation were outsourced to private and largely American contractors—even “civil affairs,” even intelligence gathering, even security, even reconstruction endeavors that in Japan had been left to the Japanese and could have been done by Iraqis with greater efficiency and far less expense. The result was a level of confusion, cronyism, non-transparency, and corruption that had no counterpart in Japan.93

In the interlude between the emperor’s announcement of capitulation in mid-August and the arrival of U.S. forces two weeks later, Japanese military and civilian officials hastened to destroy as much as possible of the paper record of their war. As a popular hyperbole had it, smoke from the air raids was replaced by smoke from burning documents. More devastating—although not publicly exposed and investigated until well over a year later—politicians, national and local officials, military officers, local police, entrepreneurs, and gangsters throughout the nation managed to spirit away gigantic quantities of finished products and raw industrial goods that had been accumulated for the ongoing war effort.

In Iraq, the counterpart to burning documents was plundering or destroying government computers and entire ministry buildings, while the counterpart to sacking the warehouses was riotous looting and vandalism in broad daylight, extending even to Baghdad’s great museums. Near the end of 2003, it was estimated that the economic cost of this pillage probably amounted to around $12 billion. The scale and impact of Japan’s “hoarded goods scandal” was surely no less in relative terms, and probably much greater. Most of the stolen or concealed stockpiles, which ranged from everyday essentials like blankets, utensils, and medicines to machinery to industrial raw materials and precious metals, were funneled into a black market that spurred inflation and crippled industrial reconstruction for several years. Other, more conventional scandals also were exposed later, including the diversion of funds earmarked for economic recovery through the Japanese Reconstruction Finance Bank.94

Where the looting in the two countries differed markedly was in the realm of public performance. In Iraq, this coincided with the arrival of U.S. forces and signaled a breakdown of public order. The failure of the Americans to even venture to suppress this was disastrous but predictable, given the absence of contingency planning. “Stuff happens” was Defense Secretary Rumsfeld’s response at a Pentagon briefing early on (on April 11, 2003). Months later (August 9), he dismissed mounting violence and chaos in Iraq with similar impassiveness: “Democracy is untidy. Freedom is untidy. Liberation is untidy.” Much of the mainstream U.S. media found press conferences of this sort entertaining. Such theater of the absurd was the beginning of the end of American credibility.

In Japan, on the other hand, the looting was quick and extraordinarily tidy, undertaken almost overnight with broad official complicity and negligible public notice. For all practical purposes, it ceased when the Allied forces arrived with their overwhelming show of might and MacArthur proceeded to make unmistakably clear who was in charge. Only a miniscule portion of the stolen or concealed goods, however, was ever recovered. Thereafter disruptive activity took other forms, such as stonewalling or heel dragging by Japanese politicians, bureaucrats, and capitalists when they could get away with it. (The phrase among students of the occupation for such practices, which were particularly conspicuous in economic affairs, is “negative sabotage.”) This happened frequently, but less frequently than counterexamples of constructive collaboration—and, in the final analysis, it was the latter that made the difference.

Combined with the extensive physical destruction of the war and inevitable disorder that followed, the diverted stockpiles and “negative sabotage” fed both a ravenous hyperinflation and nationwide black market that dominated the Japanese economic scene into 1949. In theory, the black market was illegal. In practice, it amounted to the “real” economy and almost no one could avoid participating in it as seller or buyer or both. As both cynics and appalled observers noted at the time, virtually every adult Japanese became a lawbreaker out of necessity.95

LAWLESSNESS ON THE part of the occupation forces also occurred in Japan, although nowhere near the extent to which this took place in defeated Germany and elsewhere in postwar Europe. The iconic photographs portraying friendly GIs with lively Japanese children and courteous if cautious adults were an accurate reflection of the speed with which both sides placed a human face on yesterday’s despised enemy. By both official fiat and the personal choice of conquerors with cameras in their hands, however, no one recorded crimes by the victorious forces. These were inevitable given the size of the foreign presence: the total number of U.S.-led Allied personnel in Japan was close to a half million when the occupation began, and still over a hundred thousand before the Korean War erupted almost five years later. Occupation censorship coupled with self-censorship, however, ensured that such transgressions were airbrushed out of the picture of a thoroughly benign exercise in reconciliation.

The incidence of GI (and Australian and British) crimes against Japanese nationals is impossible to quantify for several reasons. Many victims remained silent; the Japanese government had no jurisdiction over crimes by the foreigners; occupation authorities covered up incidents reported to them; and the victors rarely prosecuted such crimes. In the first two weeks of occupation, before formal censorship was imposed on September 10, hundreds of crimes and misdemeanors involving occupation forces were reported in the Japanese press. The incidence remained high for weeks to follow and ranged from drunken brawling and vandalism to theft, armed robbery, assault, and rape. Some postwar Japanese sources argue that rapes by occupation forces became more frequent as time passed.96

Criminal activity on the Japanese side increased following surrender, but in conventional ways incomparable with the bombings and ethnic cleansings that ravaged Iraq. Crime rates rose, most conspicuously in robbery, theft, and the handling of stolen goods. Unsurprisingly, many perpetrators were demobilized soldiers who returned home to find themselves unemployed and, in the burned-out cities, sometimes without homes or surviving kin. One provocative epithet—Tokkotai kuzure, or “degenerate Special Forces”—even stigmatized repatriated members of the superpatriotic kamikaze units as behaving with particularly lawless swagger. It became fashionable to speak of a breakdown of public morality, and nothing symbolized this more than the rapacious black market and emergence of prostitutes called panpan who catered specifically to the occupation forces. To Japanese conservatives, the rise of a militant labor movement was another sign of the decay of law and order, although in fact violence did not taint the movement until 1948 and even then such incidents were isolated.97

After Japan returned to prosperity beginning in the 1960s, the hardship, turmoil, and uncertainty of these early postwar years receded from view. People were dying of malnutrition; gangs controlled the black market; unemployment was high, and daily subsistence precarious for huge numbers of urban residents. Unlike later in Iraq, however, zealots were not running wild and no one was placing improvised explosives by the roadsides. Overall, order prevailed. Japanese comedians and cartoonists even ventured to find lame humor in the rise in burglary and petty theft. (Says a cartoon housewife to a burglar in her home: Everything’s been stolen from the bureau already. You might as well take the bureau itself.) It was even possible to look at the black market and the brazen panpan as possessing a resilience and vigor that, however decadent, reflected the feisty opposite of despair—and that clearly would, and did, soon end. No comparable humor or optimism found expression in Iraq.

Successful and Disastrous Demilitarization

The contrast between public order in Japan and disorder in Iraq calls attention to the most conspicuous policy area in which seemingly similar directives had vastly different outcomes: enactment of a categorical purge and dissolution of the military. On May 16, 2003, four days after arriving in Baghdad, Bremer issued “Order No. 1,” titled “De-Baathification of Iraqi Society.” This purge affected scores of thousands of mostly Sunni members at the top level of the Baath Party, including bureaucrats, managers of government-owned corporations, schoolteachers, and medical personnel. “Order No. 2,” which followed on May 23 under the imprecise heading “Dissolution of Entities,” abolished the defense ministry, related security ministries and agencies, and all existing military formations. It was promised that a new multiethnic, nonpolitical army would be established.

Estimates vary concerning how many individuals these directives made jobless (and in some cases deprived of pensions as well as salaries), but several hundreds of thousands of men, most of them possessing military skills and weapons, became part of a labor force already running at over 50 percent unemployment. Insurrectionary violence and open anti-Americanism increased thereafter, and it was in these circumstances that (on July 2) President Bush responded with taunting. “There are some who feel like—that the conditions are such that they can attack us there,” he declared. “My answer is, bring ’em on. We’ve got the force necessary to deal with the security situation.” Pugnacious rhetoric took the place of serious policy reevaluation, and wishful thinking again prevailed even as things fell apart.98

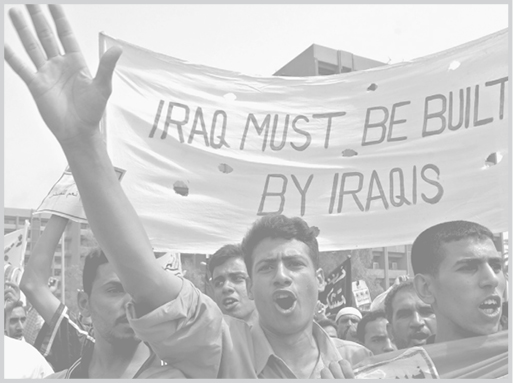

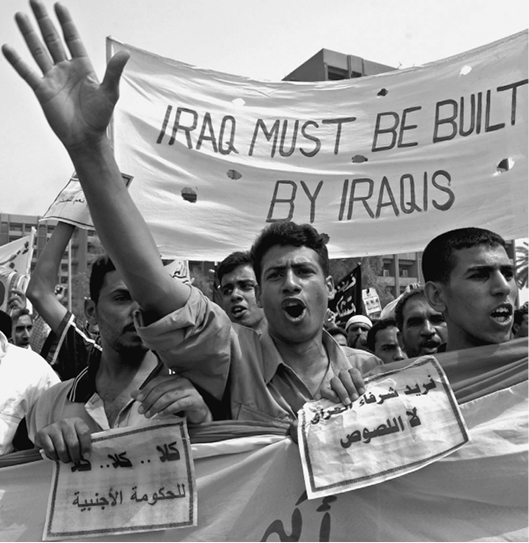

112. Shiite Muslims in Baghdad protest American intervention in the selection of post-Saddam political leaders on May 15, 2003, just days after L. Paul Bremer III arrived to assume command of the Coalition Provisional Authority. The small sign on the left reads, “No No No to the foreign government.”

In Japan, MacArthur also oversaw introduction of a political purge and the dismantling of the military. The former was not given immediate priority, and the lengthy directive ordering it—titled “Removal and Elimination of Undesirable Personnel from Public Office”—was only issued in the first week of 1946. The purge unfolded in stages thereafter, and eventually denied public employment to slightly over two hundred thousand individuals who had held positions defined by the victors as militaristic or ultranationalistic. (Allied purges in occupied Germany affected twice that number.) Although the purge in Japan resembled that imposed in Iraq in its categorical nature, as well as in offering a cumbersome appeal process, the differences were significant. Bremer described the objective of his first two orders as being to “reassure Iraqis that we are determined to eradicate Saddamism,” and his explicit model derived from the occupation of Germany rather than Japan. The Baath Party was seen as analogous to the Nazi Party, and “de-Baathification” a counterpart to “de-Nazification.”99

Policy in occupied Japan took a different direction, for there was no counterpart to the Nazi or Baath parties. The closest ideological analogue to “Nazism” or “Saddamism” was the more amorphous cult of emperor worship—the “Way of the Emperor” or “Imperial Way” (Kodo) that played so central a role in wartime indoctrination. Rather than eradicate this, the Americans early on resolved to utilize it by wooing Emperor Hirohito to their side and divesting him of some of his more spiritual ornamentation. The contradiction between exonerating the emperor while purging his most fervid and loyal servants (and indicting some as war criminals) was ignored, and what prevailed instead was a cool political cynicism. In the emperor and imperial institution, the Americans possessed—and adroitly manipulated—a potent symbol of unity, continuity, and stability. In the process, they also endorsed and perpetuated a potent symbol of paternalism, patriarchy, and blood nationalism.

While generally regarded in retrospect as riding roughshod over many individuals whose major transgression had been patriotism, the categorical Japanese purge was not socially disruptive. Career military officers constituted roughly three-quarters of those denied public positions. Around six hundred conservative politicians were banned from running for office in the first postwar general election in April 1946, which pained them more than it did the voting public. Although over eight thousand members of the economic elite were purged—including “1,535 captains of industry, finance and commerce”—capable managerial talent was available to assume their functions. Purges within the bureaucracy were small and had negligible influence. There was no schismatic impact comparable to Iraq, where “de-Baathification” translated into eliminating the Sunni technocrats and officials who dominated the party that had run the government.100

Dissolution of the Iraqi military essentially capped the disestablishment of the Sunnis, who had also dominated the officer corps, and made the prospect of Sunni-Sh’ia conflict all the more inevitable. In Japan, by contrast, the dissolution of the military establishment was a truly sweeping act that, surprisingly at first glance, was carried out without causing domestic turbulence. This radical demilitarization had rhetorical roots in the war years. Beginning in 1943, the United States and United Kingdom declared the complete and permanent disarmament of Germany and Japan to be a major war aim of the Allied coalition, and this was reiterated in the instructions sent MacArthur before his arrival in Japan, which stated that “Japan will be completely disarmed and demilitarized.” This was implemented incrementally, with the downgraded and renamed war and navy ministries handling demobilization as well as narrow tasks like minesweeping before being swept away themselves under the new constitution.101

At war’s end, Japan had slightly over seven million men under arms. The task of demobilization was formidable, and carried over into 1947. Unlike in Iraq later, it was understood that no reconstructed military establishment was in the offing. Complementary directives prohibited Japanese industry from engaging in military-related production. In a stunning symbolic stroke that caught MacArthur’s superiors in Washington by surprise, this severe antimilitary ethos was enshrined in the draft constitution that was pressed on the Japanese government by MacArthur’s headquarters in February 1946 and became law in November, after lengthy deliberation in the Diet. The new charter came into effect in May 1947.

WITHIN A FEW years, as the Cold War intensified and Japan became identified as a potential strategic ally, Washington came to regret this thoroughgoing demilitarization. Both then and afterwards, however, the Japanese populace proved unwilling to simply jettison these early antiwar ideals. The constitution still remained unrevised when the invasion of Iraq took place over a half century later; and while Japan had built substantial “self-defense” forces in the interim, their function and acceptable overseas missions remained constrained and contested. This greatly restricted Japan’s military role in the Bush administration’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq—and at the same time helps illuminate why elimination of the army and navy after the war did not prove disruptive. The nation was exhausted after its long war, which for the Japanese dated back to 1937. Sixty-six cities lay in ruins; around ten million people were homeless; the national death toll came to some two million fighting men and over a half-million civilians; and it was calculated that somewhere around 80 percent of the millions of servicemen being repatriated from overseas were injured or ill. In the wake of disastrous defeat, the once-revered imperial military had no constituency.

The pervasiveness of cynicism vis-à-vis the military and militarists was captured in a phrase that became popular after the surrender: damasareta, “we were deceived.” The military had become ascendant in the 1930s in a society that was not inherently and incorrigibly militaristic, and its demise had little bearing on maintaining domestic law and order. Millions of demobilized servicemen returned to their homes in the largely unscathed countryside; several million joined the ranks of the burgeoning labor movement; and most officers found their technical and administrative skills adaptable to the tasks and challenges of reconstruction. The human resources hitherto devoted to war service and war production were agnostic and primed—both technically and psychologically—for redirection into nonmilitary pursuits.

Abolition of the war and navy ministries—and of many of the economic controls they had assumed in the process of mobilizing for “total war”—was also welcomed by most capitalists and had a profound effect on the central bureaucracy. After years of kowtowing to the militarists, civilian ministries assumed command, led initially by the Ministry of Finance. In this somewhat unexpected manner, MacArthur’s version of the “dissolution of entities” strengthened the indigenous administrative structures through which the Americans promoted their agenda.

“Generalists” versus “Area Experts”

One of the more popular canards about the U.S. failure in Iraq is that most of the Americans who planned or manned the post-invasion occupation knew little beforehand about that country or the Middle East more generally. This is exaggerated but largely true. It is also something of a red herring. Hundreds of articulate Iraqi exiles and Middle East specialists participated in the private as well as public discussions and debates that preceded the invasion. It can even be argued that their factionalism and disagreements should have been yet another clear warning of the problems that lay ahead. This never occurred in the case of planning for postwar Japan, primarily because there was no politically energized Japanese exile community.

The larger red herring, in any case, is revealed by the fact that the same criticism can be directed at most of the Americans later praised for promoting the reformist agenda in defeated Japan. Few spoke Japanese or knew anything about Japan beforehand, and “generalists” and technical specialists were the prized recruits. To a considerable degree, this reflected deliberate bias and not just the exceedingly small number of Westerners who could even qualify as knowledgeable about Japan. When the legal expert Alfred Oppler, born and educated in Germany, was recruited to take a leading role in revising Japan’s entire legal system, his experience was the rule rather than an exception. Upon reporting to Tokyo (in February 1946), Oppler confessed that he “did not have any knowledge of things Japanese.” “Oh that is quite all right,” the colonel who greeted him replied. “If you knew too much about Japan, you might be prejudiced. We do not like old Japan hands.”102

Martin Bronfenbrenner, who served as a young economist in the occupation and went on to a distinguished academic career, made much the same observation for his own area of expertise. “The American Occupation forces were ill prepared to deal with Japan’s economic problems,” he later wrote. “Most of its civilian and military personnel were temporary employees, with little prior training or interest in things Japanese. As the Occupation progressed, they were also subject to adverse selection, with many of the best and most promising people taking more permanent or prestigious ‘stateside’ jobs, or going into private trade or professional practice in Japan when permitted to do so.”

“At the outset,” Bronfenbrenner went on, “most SCAP employees had but vague notions of the workings of the Japanese economy, and these were colored by wartime propaganda. Two extremes were in evidence: one saw the Japanese as backward ‘Asiatics’ in need of the charity and enlightenment of the West; the other saw the country capable of high productivity and economic advance if freed from the ‘exploitation’ of the zaibatsu, large landlords, and the government bureaucracy. Early policy was guided by an amalgamation of these views, coupled with political considerations, punitive attitudes (sometimes racist), and incomplete or inaccurate knowledge.”103

Area specialists—and Japan specialists in particular—were regarded with suspicion by occupation planners on the often plausible grounds that they were biased by their cultural fixations and frequently insensitive to the more universal aspirations people share in common. An “old Asia hand” of World War II vintage, that is, would often argue that for cultural or historical reasons democracy or meaningful popular self-governance could not be expected to take root in Japan or anywhere else in Asia for that matter. Joseph Grew and the wartime coterie of State Department specialists known as the “Japan Crowd” exemplified this, as Grew made clear on many occasions. Just weeks after Japan’s surrender, for example, he wrote to an acquaintance (and later reproduced the letter in his memoirs) that “any attempt to impose an outright democracy on the Japanese would result in political chaos and would simply leave the field wide open for would-be dictators to get control. One can’t live in a country for ten years without knowing these things.”104

George Sansom, a British diplomat and widely admired cultural historian who was first posted to Japan in 1904 and spent many years preparing internal reports on Japan’s economy, was even more disdainful of SCAP’s early reformist agenda. In December 1948, more than three years after the surrender, he contributed a foreword that bristled with scorn to a book on the Japanese economy in war and reconstruction. “This is not the place for a discussion of the policy of democratization which has been energetically, if at times unrealistically, pursued,” Sansom wrote, “but it is pertinent to observe that parliamentary democracy was born and nourished in the West in relatively favorable economic conditions. It may be that hungry, ill-clothed and worried men in some countries will pour their energies into a struggle for political freedoms; but it is extremely doubtful whether Japan is one of those countries.”105

A liberal New Dealer, on the other hand, as well as a traditional Republican champion of petite entrepreneurship like MacArthur, would argue otherwise. Colonel Charles Kades, the highly respected Government Section lawyer who had been a New Dealer and led the team that drafted the new constitution, made this philosophy amply clear—drawing on principles of universal human rights and aspirations that were then finding expression in the fledging United Nations. MacArthur, on his part, expounded at one point that “history will clearly show that the entire human race, irrespective of geographical limitations or cultural tradition, is capable of absorbing, cherishing and defending liberty, tolerance and justice, and will have maximum strength and progress when so blessed.”106

This was a provocative divide in which “generalists” on both the political left and right tended to argue the universal applicability of fundamental rights and principles, while the putative “area experts” were inclined to focus on historical and cultural peculiarities that made non-Western societies inhospitable to values like “democracy.” Often this attitude reflected not merely the inclination of area specialists to zero in on ostensibly incompatible differences, but also the class consciousness and arrogance of a diplomatic cohort that spent its career associating professionally and socially with foreign elites who regarded the lower classes in their own countries as ignorant and incapable of governing themselves. No matter how incompetent, autocratic, or militaristic those native elites might prove to be, at least they had received higher schooling, attended the right clubs, and in most cases spoke English. (Grew’s meticulous private diary covering his ten years in Japan is, among other things, a chronicle of upper-class snobbery, with many of his most admired Japanese acquaintances and informants associated in one way or another with court circles.)

At a superficial level, somewhat the same sort of disagreement played out in the Bush administration’s war of choice against Iraq. On the one hand, a chorus of neoconservative ideologues in particular—as well as solo performers such as President Bush and Prime Minister Blair—argued not only that Iraq was ripe for democracy but also that bringing this about there by violent regime change would have a ripple or domino effect throughout the Middle East. Blair, for example, channeled the MacArthur-like language of universality in a much-applauded speech before a joint session of Congress on July 17, 2003, when the bloom was fading rapidly from Operation Iraq Freedom and it was clear “democracy” would have to replace nonexistent weapons of mass destruction as the major rationale for the invasion. “Ours are not Western values,” Blair declared, “they are the universal values of the human spirit. And anywhere . . . anywhere, anytime ordinary people are given the chance to choose, the choice is the same: freedom, not tyranny; democracy, not dictatorship; the rule of law, not the rule of the secret police.” Those who criticized the invasion were dismissed as being guilty of old-fashioned racism and ethnocentrism, and guiltiest of all in this polemic were “Arabists” in and outside the State Department.107

The disdain of White House and Pentagon planners for Middle East experts apart from those who endorsed the neoconservative argument runs as a leitmotif through much (not all) insider and investigative writing on the Iraq war. Timothy Carney, who served under Jay Garner in the short-lived Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, for example, later emphasized how lacking in critical personnel this office was when it arrived in Baghdad. “There were scarcely any Arabists in ORHA in the beginning” at a senior level, he observed. “Some of us had served in the Arab world, but we were not experts, or fluent Arabic speakers.” This was deliberate in his view, for Pentagon officials “said that Arabists weren’t welcome because they didn’t think Iraq could be democratic.”108

This approximated, almost to the word, what Alfred Oppler and other recruits in the occupation of Japan had been told about the “old Japan hands.” Sometimes, however, the area experts do have knowledge and insights worth being heeded.

Early in 2004, some months after the ORHA had been replaced by Bremer’s Coalition Provisional Authority, Jay Garner told an interviewer that when the ORHA found itself facing an enormous array of postwar challenges, with no blueprint in hand, it immediately concluded there was no alternative but to “bring in contractor teams, as fast we could do it.” This was not merely a desperate makeshift reaction, but a modus operandi already being promoted in Washington. “Outsourcing” was the magic word—and perhaps the closest the government really came to having a “plan” for post-conflict Iraq. Whatever nation building took place would be privatized.109

In early occupied Japan, the counterpart economic mantra was very different: “economic democratization.” As formulated in the Initial Post-Surrender Policy for Japan, and frequently repeated, this reflected a consensus that stability, prosperity, and future peace were best assured by promoting the reorganization of industry, finance, commerce, labor, and agriculture in ways that would “permit a wide distribution of income and of the ownership of the means of production and trade.” Both land reform and a strong labor movement were rationalized as forms of liberation that would create a more dynamic domestic market—and, in the process, thwart any possible threat of communistic revolution from below while simultaneously eliminating future need to capture markets abroad. In a similar vein, MacArthur denounced the huge family-controlled zaibatsu conglomerates as both vestiges of “feudal lineage” and a perverse form of socialism in private hands—“a standing bid for State ownership,” in his alarmist words, “and a fruitful target for Communist propaganda and collectivist purposes.” Both the Republican supreme commander and his New Dealer trust busters believed that breaking up these great conglomerates would stimulate competition and hasten the emergence of a dynamic middle class.110

At the same time, MacArthur’s reformers tolerated and even promoted the visible hand of the state. Certain measures and mechanisms that the Japanese government had introduced to stimulate the wartime economy were retained; ministries responsible for finance and industry were strengthened; new planning agencies and eventually (in 1949) an entirely new Ministry of International Trade and Industry were introduced. Particularly after 1948, SCAP’s own bureaucracy became deeply involved in economic planning aimed at stimulating recovery and making Japan “self-sufficient” by giving priority to an export-oriented manufacturing sector. After war erupted in Korea in 1950, this intervention extended to introducing legislation that would continue to protect the economy from foreign carpetbaggers after Japan regained sovereignty. The other side of endorsing “self-sufficiency” was thus a consensus that capitalist economies require reasonable protection from international as well as domestic predators, particularly at early and vulnerable stages of development.111

Even after the Cold War prompted retreat from radical policies regarding capital and labor and the redistribution of wealth, Americans engaged in Japan policy would have found remarkable the free-market fundamentalism that saturated U.S. policy in Iraq—the notion, that is, that an unregulated marketplace is fundamentally rational, let alone invariably beneficial to societies or the global economy more generally. They would surely have been appalled at the notion of turning over basic reconstruction tasks to foreign, profit-driven private interests. Beyond an old-fashioned moral aversion to letting greed run rampant, this earlier generation was sensitive to the social disruptiveness and political blowback of unregulated capitalism. Where Japan in particular was concerned, they also were keenly aware of the necessity of maintaining the trust essential to stable long-term relations by avoiding even the appearance of exploitation or economic imperialism.

The practical benefits of adhering to such economic prescriptions in the crisis situation of the time were considerable. On the U.S. side, the occupation escaped becoming a host to mercenaries or feeding trough for profiteers, and the United States emerged with its reputation for integrity intact. Japan regained sovereignty as a capitalist democracy with a mixed economy and a level of protectionism that gave both the ruling groups and general populace a certain sense of security. And the nation was set on a path of reconstruction that ended, three decades later, in Japan’s emergence as the second most powerful capitalist state in the world, with the great majority of its citizens identifying themselves as “middle class.”

THERE WAS MORE than a little hypocrisy in the fanfare about “privatization” that became associated with the occupation of Iraq, for on the U.S. side the state and private sector became as close as hand and glove. Nation building was turned over to entrepreneurs, with contractors usually guaranteed cost-plus profits funded with taxpayers’ money. In an article published on July 1, 2004, coincidental with the termination of the CPA, a Washington-based journal catering to civilian and military officials framed the contradiction succinctly: “From the outset, the only plan appears to have been to let the private sector manage nation-building, mostly on their own.” Once this door was opened, effective governmental monitoring and oversight virtually disappeared. What was left was essentially an American-style version of security-focused state capitalism, dominated by the rough equivalent of what Japanese in the 1930s and early 1940s had called “national policy companies.”112

In practice, this reliance on the private sector to carry out post-combat responsibilities probably came as close to a preinvasion “plan” as existed. Because war planning was conducted in supersecrecy, however, and because this was accompanied by elaborate public-relations manipulation (including denying that the decision to go to war had been made), it was difficult to set such activity in motion. Interagency discussions about recruiting contractors for reconstruction tasks began around September 2002, but it was not until the following January that the first few contracts were awarded under the auspices of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). On February 13, the agency produced a thirteen-page document titled “Vision for Post-Conflict Iraq” that was made available to the Wall Street Journal, which publicized its contents in detail on March 10.

The Journal article drew wide attention. It reported that contracts totaling $900 million had been extended to five U.S. infrastructure engineering firms whose work was projected to be completed in eighteen months, creating “a new framework for economic and governance institutions.” The key reconstruction problems to be addressed were identified as water systems, roadways, seaports and airports, health services, schools, and electrical generation. (The oil industry was not mentioned, although this received close attention in other preinvasion reports and commentaries.) Other contractors were still being sought, and required security clearance to be eligible. Even before the U.S. military had set foot in Iraq, the target nation’s own skilled workforce was obviously deemed incapable of handling such engineering projects. As one Iraqi businessman observed bitterly some months later, when these contracting arrangements were in full flood, “They claimed that we were smart enough to build weapons of mass destruction capable of threatening the world, but now they treat us like red Indians on a reservation at the end of the 19th century.”113

The Journal described the USAID project as harbinger of “the largest government reconstruction effort since Americans helped to rebuild Germany and Japan after World War II”—a description that quickly became a golden fleece dangled by business lobbies, with visions of billions rather than hundreds of millions of dollars in the offing. On May 1, the same newspaper drew even greater attention to the privatization agenda, this time with a front-page article headlined “Bush Officials Draft Broad Plan for Free-Market Economy in Iraq.” The basic source for this piece was a hundred-page document drafted largely under the Treasury Department titled “Moving the Iraqi Economy from Recovery to Sustainable Growth,” which had been circulated among financial consultants in February, prior to the invasion. This text was quoted as promoting “a broad-based Mass Privatization Program”—and the Journal’s lead paragraph did away with any possible lingering notion that Iraq really belonged to the Iraqis, as Rumsfeld had declared to applause in his “Beyond Nation Building” speech, or that the United States really intended to leave quickly. The article began as follows: “The Bush administration has drafted sweeping plans to remake Iraq’s economy in the U.S. image.”114

The bipolarity reflected in this abrupt transformation from being “beyond nation building” to being engaged in “sweeping plans” to create a little America on the Tigris found institutional form in the hastily created Coalition Provisional Authority. It was not until UN Resolution 1483 of May 22 validated the U.S. and British-led CPA that the word “occupation” actually became operative. Almost simultaneously, “nation building” began coursing through conservative circles in unexpected and discordant ways. One of the early technical advisers recruited by the CPA recalled (with some alarm) that “without exception” his fellow passengers on the flight to Baghdad were reading books not about Iraq, but about the occupations of Japan and Germany. Some months later, the conservative intellectual Francis Fukuyama voiced concern that the United States was only engaging in “nation-building ‘lite’ ” (the repudiated State Department language of almost a year earlier) and not going far enough. Other conservatives were concerned for contrary reasons. When Condoleezza Rice belatedly assumed greater responsibility for Iraq (in early October), for example, her trusted adviser Robert Blackwill was assigned to look into the situation and responded in keeping with earlier apprehensions regarding occupation and nation building. “I don’t like the way things are going over there,” he was quoted as saying. “I don’t like the political vibration. I don’t like this idea of occupation.”115

Rendering Iraq “Open for Business”

Like it or not, Iraq was, as Bremer declared a few weeks after arriving, “open for business again.” He might have added: and as never before. The initial occasion for this often-repeated comment was Resolution 1483 and the subsequent lifting of the economic sanctions that had been imposed on Iraq in 1990, but there was no intention to simply return to the status quo ante. Iraq’s protective trade restrictions were abolished as soon as possible, with the import tariff eventually fixed at only 5 percent, paving the way for a flood of foreign imports. Bremer never lost an opportunity to explain the reasoning behind the CPA’s shock program of sweeping privatization. “A free economy and a free people go hand in hand,” he explained, and what this meant more specifically was that “substantial and broadly held resources, protected by private property, private rights, are the best protection of political freedom.” In this context, “de-Baathification” signaled a great deal more than carrying out a political purge of the top levels of Saddam’s police state. It also signified thoroughgoing deregulation of what Bremer referred to as the “Baathist command economy” and Saddam’s “cockeyed socialist economic theory.” Rumsfeld’s parallel phrasing as the CPA came into existence and occupation replaced liberation was “market systems will be favored—not Stalinist command systems.”116

The CPA’s privatization agenda peaked in September 2003, with issuance of several orders. Order No. 37 established a flat tax rate of 15 percent, drastically reducing the burden on corporations and wealthy individuals. (This was another contrast to occupied Japan, where serious tax reform was not even addressed until 1949. The sweeping changes introduced at that time followed recommendations by a mission headed by Carl Shoup, stressed equity, and provided various tax breaks for companies—but at the same time instituted new taxes on capital gains, interest, accessions, and net worth, as well as a value-added tax.)117

Bremer’s Order No. 39, which provoked the most intense responses pro and con, called for privatizing state enterprises, permitting 100 percent foreign ownership of Iraqi firms, tax-free repatriation of all investment profits, and forty-year leases on contracts. Under Order No. 40, privatization was extended to the banking sector in keeping, again, with the goal of “transition from a non-transparent centrally planned economy to a market economy characterized by sustainable economic growth through the establishment of a dynamic private sector.” Rumsfeld praised these reforms in Senate testimony on September 24, 2003, for creating “some of the most enlightened—and inviting—tax and investment laws in the free world.” The Economist described them as “a capitalist dream”—albeit not without cynicism, for this frequently quoted phrase appeared in an article titled “Let’s All Go to the Yard Sale.”

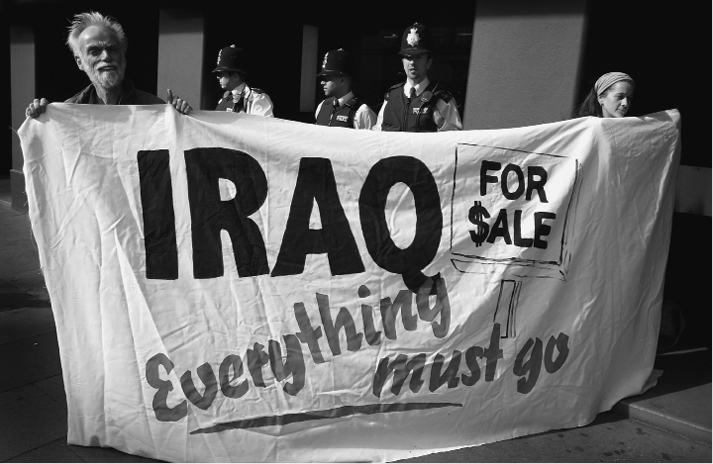

113. Demonstrators protesting occupation policies outside a “Doing Business in Iraq” conference and exhibition in London, October 13, 2003. The “Iraq for Sale” catchphrase became ubiquitous in the wake of CPA announcements of plans to drastically privatize the Iraqi economy and open it to foreign investment.

Such popular perception that Iraq was not merely occupied but now also for sale does not appear to have given pause to the Americans who temporarily exercised sovereignty there. Apart from the rationality or irrationality of the CPA’s orders—and no one denied the inefficiency and corruption of most Baathist economic institutions—what was particularly ill-conceived about this free-market jihad was its disregard of politics, mass psychology, and public appearance. Dreamers and critics alike spoke of a gold rush—and the critics, more precisely, of “blood money,” “a license to loot the land,” “a carpetbaggers’ free-for-all.” Iraqis themselves, blue collar and bourgeois alike, were appalled, and for good reason. As a former State Department official recalled the atmosphere in official Washington, “There was little interest in bringing in governments and companies from countries that had not supported the war. What motivated this view was a sense that to the victor should go the spoils, and that French and Russian firms should not benefit in any way given their opposition. . . . It is extraordinary that many people throughout the U.S. government thought Iraq was a jewel to hoard and not a burden to share. But they did.”118

114. Bilingual banner at a Sunni demonstration in front of the Baghdad headquarters of the Coalition Provisional Government, November 7, 2003. The demand for autonomy is presented as a fatwa, or Islamic religious decree.

The frenzy to get in on the spoils was remarkable. A two-day “Rebuilding Iraq Conference” convened in Virginia that attracted hundreds of potential contractors and investors in late August, just before the key privatization orders were issued, typified this. A former secretary of defense (William Cohen) and former secretary of commerce (Mickey Kantor) were featured speakers. Bremer’s “Iraq is open for business” statement headlined one version of the online advertising for the conference. The Wall Street Journal’s quote about “the largest government reconstruction effort” since Germany and Japan was recycled. The Council on Foreign Relations was cited as estimating “it will cost nearly $100 billion to rebuild Iraq”—and this was immediately trumped by noting that the Center for Strategic Budgetary Assessments “has calculated that the non-military rebuilding costs could near $500 billion.” Iraq was described as “the newest, most lucrative and fastest growing market,” a land with “enormous business potential.”119

By year’s end this euphoria had largely crashed to ground, but warning signs were present from the outset. The Wall Street Journal’s preinvasion article comparing USAID plans for Iraq to rebuilding Japan and Germany quoted a respected international-affairs expert, Anthony Cordesman, cautioning that it was essential to “convince the world that this is not profiteering.” Immediate responses in the foreign press confirmed this would be difficult and probably impossible to do. The Asia Times, for example, summoned the language of a bygone age of turn-of-the-century imperialism vis-à-vis China by observing that “needless to say, the ‘scramble for Iraq’ is on.” Coming from a different direction, politicians as well as businessmen excluded from the initial contracting process decried the “crony capitalism” of secret deals with companies known to have close Republican connections.120

When the Journal later publicized “plans to remake Iraq’s economy in the U.S. image,” its own page-one article again warned that this would be “controversial” and “contentious.” Such plans were likened to the shock policies free-market apostles had introduced a decade previously in Russia and other countries of the former Soviet bloc, which met with decidedly mixed success as, in the Journal’s words, “rapid privatization of state-run enterprises led to sharp disruptions in jobs and services, as well as rampant corruption.” This seemed increasingly prophetic as U.S. contractors began rushing into Iraqi while state-run companies remained in limbo, unemployment increased, and the infrastructure continued to deteriorate—all the more so when the State Department sponsored a conference of “VIPs” in the fortressed Green Zone in Baghdad simultaneously with the September issuance of the CPA’s privatization orders and included Yegor Gaidar, the architect of Russia’s draconian economic reforms, as a featured speaker.121

Even as promotion of the free-market reforms was at its peak, moreover, specialists in international law were observing that drastic privatization was probably illegal. This, too, was predictable. On May 22, just as the CPA settled in for business, the British weekly New Statesman leaked a secret memorandum to Prime Minister Blair from Lord Peter Goldsmith, the attorney general (who had previously declared the military invasion itself lawful, given the danger of Saddam’s alleged weapons of mass destruction). Dated March 26, a week after the invasion began, this questioned the legality of the occupation in general and warned in particular that “the imposition of major structural economic reforms would not be authorized by international law.”122

This commotion over economic policy threw particularly harsh and focused light on the general issue of the legality of the occupation. Attorneys representing the U.S. government and CPA maintained that drastically altering the existing economic system had been legitimized by Resolution 1483, since this was necessary to promote “effective administration” and “economic reconstruction and the conditions for sustainable development”—objectives endorsed by the United Nations. Many legal experts, on the other hand, pointed out that the CPA’s privatization orders violated not only the Hague and Geneva provisions cited in the poorly drafted UN resolution, but also the U.S. Army’s own field manual The Law of Land Warfare (which also reiterated the Hague and Geneva guidelines), as well as the Iraqi constitution (which, among other things, declared constitutional revision without the consent of the Iraqi people unlawful, barred private ownership of “national” resources or “the basic means of production,” and explicitly prohibited foreign ownership of real estate or the establishment of companies by non-Arabs).123

This debate quickly became moot, for by the time the CPA closed shop on June 28, 2004, the vision of a gold rush already seemed like an opium dream. The “lucrative and fastest growing market” did not materialize. Chaos prevailed instead. Although the occupation had ended in name, however, it was not over in practice. U.S. forces stayed on, as did the foreign contractors with their lucrative public contracts, but market fundamentalism was dead as a policy prescription for Iraq. Three years later, beginning with the crash of the U.S. economy, it was all but dead worldwide—and the privatization mania in occupied Iraq, so damaging in so many ways, became emblematic of a much broader epoch of ideological wishful thinking.

In September 2003, as these economic controversies regarding Iraq peaked amidst mounting political and social turmoil, President Bush again found it appropriate to offer defeated Japan and Germany as bright mirrors for Iraq. “America has done this kind of work before,” he told the nation on September 7. “Following World War II, we lifted up the defeated nations of Japan and Germany, and stood with them as they built representative governments. We committed years and resources to this cause.” On September 23, speaking before the UN General Assembly, he spoke of approaching Congress for “additional funding for our work in Iraq—the greatest financial commitment of its kind since the Marshall Plan.”

The Marshall Plan comparison was natural, even irresistible—and more or less accurate insofar as eventual ballpark aid figures are concerned. By one careful estimate, U.S. aid allocations appropriated for Iraq from 2003 to 2006 totaled $28.9 billion, out of which $17.6 billion (62 percent) was directed to economic and political reconstruction and the remainder to improving Iraq security. This report, issued in March 2006 by the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress, concluded that “total U.S. assistance to Iraq thus far is roughly equivalent to total assistance (adjusted for inflation) provided to Germany—and almost double that provided to Japan—from 1946–1952.” Converted to 2005 dollars, overall U.S. aid to Germany translated into a total of $29.3 billion, of which the Marshall Plan accounted for $9.3 billion. Over the same 1946–52 period, total assistance to Japan (where the Marshall Plan did not apply) amounted to roughly $15.2 billion in 2005 dollars, although the bulk of this was not directed to rehabilitating the economy.124

Quantitative comparison alone, however, is misleading. As with so many other matters pertaining to World War II and its aftermath, Winston Churchill became the most quoted phrasemaker for the Marshall Plan, famously describing it as “the most unsordid act in history.” This was plausible hyperbole for what amounted to enlightened self-interest. The Marshall Plan, and economic aid programs for Europe and Japan more generally, served America’s interests in several ways—not least, by helping to reconstruct and eventually integrate foreign economies that would provide markets for U.S. exports. This was explicit in the crisis vocabulary of official Washington in those times, which emphasized not only the vulnerability to communism of economically weak states in Europe and Asia, but also looming overproduction in the United States and a “dollar gap” that prevented foreign markets from absorbing this.125

OCCUPIED IRAQ AND THE LONG WAR

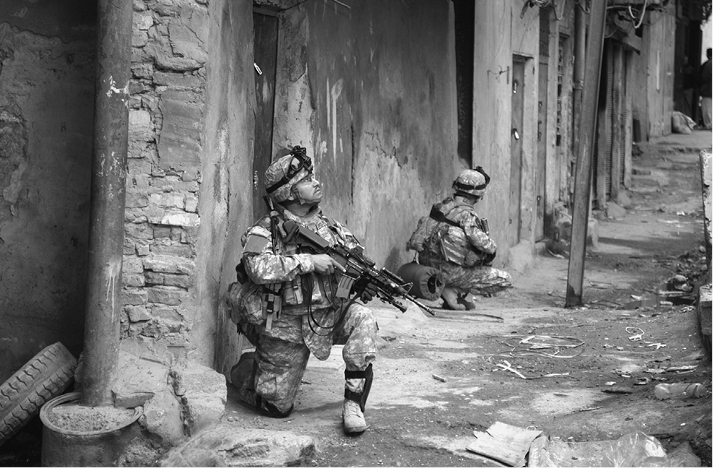

To the end of the Bush presidency in January 2009, the visual record of this long war conveys a terrible stasis—terror, insurgency, ceaseless insecurity on the part of both the occupied and the U.S.-led military forces that occupied and patrolled them. American and British troops remained as tense and combat ready in 2008 as they were during the early weeks of Operation Iraqi Freedom more than five years earlier. The generic snapshots treasured by foreign photographers in occupied Japan some six decades earlier, depicting friendly soldiers interacting with local children, are also present for Iraq—but the soldiers are always armed to the teeth, and the children often injured. There are no counterparts to the soft subjects that attracted Westerners in occupied Japan—no scenes of socialization and fraternization, no discovery of the picturesque, no infatuation with indigenous traditions, no evocation of the feminine, the exotic, the mildly erotic. Year after year, anxiety, pain, trauma, protest, and grief draw the camera’s eye.

115. November 12, 2004: U.S. soldiers rush a wounded comrade to a helicopter during operations in Fallujah.

116. March 5, 2005: A few weeks short of the beginning of the third year of occupation, a GI stands guard over a mother with two children during a routine house search in the northern city of Mosul.

117. January 11, 2007: American soldiers conduct a joint cordon and search operation with Iraqi army personnel in Baghdad.

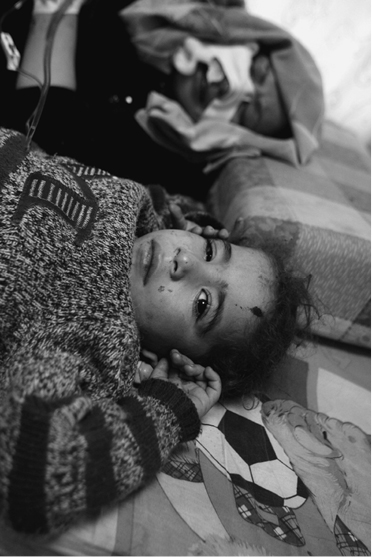

118. December 27, 2008: A mother and her three-year-old daughter lie in a Baghdad hospital after being injured in a car bombing in which twenty-two people were reported killed and fifty-four injured.

119. July 12, 2008: A woman in Baghdad’s Sadr City protests the detention of men seized in a house raid jointly conducted by U.S. and Iraqi forces.

COSTS OF WAR

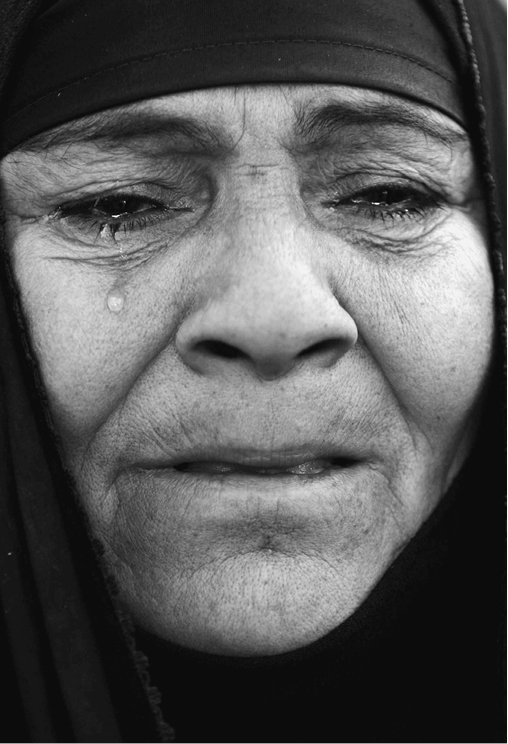

120. November 1, 2008: A woman weeps at a rally in Karbala demanding government aid for those widowed or orphaned following the U.S.-led invasion in 2003. When the Bush presidency ended, the human costs for Iraqis of its war of choice defied exact measurement but were in every respect tragic. The number of documented civilian deaths caused by terror, insurrection, and military operations between the invasion and January 2009 was around a hundred thousand, while serious estimates of violent deaths beyond the official numbers ran into the many hundreds of thousands. Estimates by Iraqi agencies of the number of children who had lost one or both parents ranged from one million to as many as five million, with a report released in January 2008 putting the number of homeless orphans at a half million. Around two million Iraqis, including a significant portion of the middle class, fled abroad after the invasion, mostly to neighboring countries. More than two million additional Iraqis had been internally displaced.

More striking are the temporal, temperamental, and ideological differences between the post–World War II reconstruction agendas and Iraq. Where the first of these—timing—is concerned, economic reconstruction did not become a priority in occupied Germany and Japan until two to three years after the war ended. In both defeated nations, initial U.S. economic objectives were overwhelmingly directed at “economic disarmament” and “permanently” eliminating economic domination of neighboring countries. Accordingly, occupation authorities were explicitly ordered to take no actions aimed at “economic rehabilitation.”

The basic directive to the commander in chief of U.S. forces in occupied Germany (dated April 26, 1945) made this eminently clear. “Germany’s ruthless warfare and the fanatical Nazi resistance have destroyed the German economy and made chaos and suffering inevitable,” this guiding document declared, and “the Germans cannot escape responsibility for what they have brought upon themselves.” The clear and pressing goal was “the industrial disarmament and demilitarization of Germany” through reparations and severe restrictions on industrial production, and to this end, the U.S. commander was told, “You will take no steps (a) looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany, or (b) designed to maintain or strengthen the German economy.” Beyond economic disarmament per se, this severe policy aimed at ensuring that “basic living standards” in Germany did not exceed “that existing in any one of the neighboring United Nations.” This was not rescinded until July 1947, when a new Joint Chiefs of Staff directive (JCS 1779) affirmed that “an orderly and prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany.” Prior to then, a considerable part of German heavy industry was dismantled for reparations, and severe restrictions were placed on production in critical sectors such as steel.126

Economic policy in Japan followed a similar course. Like the precedent directive for Germany, the Initial Post-Surrender Policy for Japan minced no words on this. “The policies of Japan have brought down upon the people great economic destruction and confronted them with the prospect of economic difficulty and suffering,” this guiding document observed, and then immediately proceeded to declare that “the plight of Japan is the direct outcome of its own behavior, and the Allies will not undertake the burden of repairing the damage.” In this same punitive spirit, again following the model for Germany, initial reparations policy envisioned using the dismantling and overseas relocation of factories and the like not merely to compensate Japan’s victims, and not merely to raise standards of living elsewhere in Asia, but also to ensure that such standards within Japan did not exceed those of neighboring countries.127

When one of the most disastrous harvests in decades followed hard on the heels of Japan’s surrender, the United States responded with aid in the form of foodstuffs, fertilizer, and the like; the explicit objective of such humanitarian aid was to prevent social unrest that might imperil the occupation agenda. It was not until 1948 that a series of economic missions from Washington called for suspending reparations, lifting restraints on industrial production, abandoning the economic deconcentration program, curbing labor-union activity, laying off workers in the public sector in particular, and promoting production for export even at the cost of a decline in already precarious living standards. The key document that established economic reconstruction and production for export as the new “prime objective” of the occupation in Japan (NSC 13/2) was approved by the National Security Council that summer and not signed by Truman until October.128

There was no rationale in Iraq for the punitive economic neglect originally mandated in Germany and Japan—and, more critically, no time for such procrastination. The Germans and Japanese could be left for a while to stew in their own juices, as the more vindictive language of the times often put it, but this was not feasible in ostensibly liberated Iraq. By choice, America’s preemptive war placed Iraq at the center of the war on terror and center of global policy, making it a touchstone for what the United States could and would do as a great power politically and economically as well as militarily. There was no time to lose in making Iraq stable in every way—and, in practice, year after year passed with such precious time lost beyond recall.

THE TEMPERAMENTAL DIFFERENCES between economic planners in the early Cold War years and later, in the post–Cold War invasion of Iraq, are as striking as the differing windows of time. The belated decision to become actively engaged in promoting economic reconstruction in Europe in particular was undertaken with scrupulous care to avoid any appearance of impropriety. Probity was taken seriously, and so was the psychological as well as practical necessity of ensuring that recipients of U.S. aid played major roles in prescribing as well as administering the funds involved. Some seventeen nations in Western Europe ultimately benefited from the Marshall Plan (with Germany ranking behind Britain, France, and Italy in total aid received); and the recipients themselves took the lead in determining how the money would be used, with the United States exercising veto power over spending plans. European participation was conducted through the Committee on European Economic Cooperation (later renamed the Organization for European Economic Cooperation), which laid the groundwork for subsequent advances toward European unity.

This multinational structure of policy making and administration proved to be pragmatic, creative, and psychologically shrewd. At the same time, it was flexible and eclectic in catering to a diversity of national, political, and cultural as well as economic circumstances—necessarily and obviously so, administrators would have said at the time, although such distinctions and qualifications would be largely derided by the later believers in one-size-fits-all market fundamentalism. The program was also transparent and accountable. Congress created an independent Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA) that lasted only for the four-year duration of the Marshall Plan and was subjected to annual review before additional funds were appropriated. Staffed throughout its short life by individuals of considerable distinction drawn from both the public and private sectors, the ECA was applauded for avoiding politicization and corruption.129

Economic aid earmarked explicitly for reconstruction in Japan was comparatively modest. Most of the aid directed to Japan between 1946 and 1952 was administered through the U.S. government’s GARIOA (Government Aid and Relief in Occupied Areas) program. This took the form primarily of food, agricultural supplies and equipment, and small amounts of medical supplies and the like, and totaled roughly $1.2 billion in value in then-current dollars ($7.9 billion in 2005 dollars). Infrastructure aid per se did not commence until mid-1948, under the so-called EROA (Economic Rehabilitation in Occupied Areas) program. Consisting primarily of machinery, industrial raw materials, transportation-related aid, and the like, this came to a total value of around $785 million ($5.2 billion in 2005 dollars). Additionally, as a vehicle for increasing the impact of the aid packages, beginning in 1949 the Japanese government directed some $845 million in yen proceeds from the sale of U.S. aid goods into a Counterpart Fund mechanism (also implemented in Europe) that committed the Japanese government to providing matching domestic funds for industrial reconstruction.130

In both Europe and Japan, the bureaucratic promotion of reconstruction was largely disciplined and professional—and, of inestimable importance, involved intimate participation by the recipients. (It did not, at the same time, escape some corruption on the Japanese side.) This is particularly noteworthy when set against, first, the notorious degree to which Iraqis were excluded from serious policy making during the reign of the CPA; and, second, the privatization, cronyism, ideological litmus tests, failures of oversight and auditing, unfulfilled promises, and outright corruption that came to be associated with appropriations for reconstruction in Iraq. The latter practices did not merely make “sordid” rather than “unsordid” a commonplace description of what actually transpired. In the eyes of much of the world, including the Iraqis, they made a mockery of all the high language about the rationality, efficiency, and discipline of economies structured (borrowing the Wall Street Journal’s phrase) “in the U.S. image.”

THIS TEMPERAMENTAL DISCONNECT between the early Cold War planners and their post–Cold War counterparts went hand in hand with disparate ideological attitudes regarding bureaucratic competence and responsibility on the one hand, and private-sector efficiency and rationality on the other. This is not to deny ideological resonance across the generations. Once the late-1940s planners in Washington concluded that Germany and Japan had to be rehabilitated as the major “workshops” of a noncommunist Europe and Asia, respectively, concerted attention was devoted to increasing their productivity, improving their managerial skills, and integrating them into regional and global market systems capable of resisting and containing Soviet (and, quickly, Chinese) communism. Where Asia in particular was concerned, from 1949 on U.S. planners became fixated on closing off trade with China and developing tight, hierarchical trade relations linking Japan, Southeast Asia, and the United States—a vision of market integration that some planners referred to privately as a little “Marshall Plan for Asia.” Early preoccupation with creating a viable domestic Japanese market by liberating workers and peasants gave way to promoting the interests of capital and coupling production for export with enforcing domestic austerity, while simultaneously undermining the influence of organized labor and the political left.131

These revised policies for the former Axis enemy were explicitly framed in terms of the “serious international situation created by the Soviet Union’s policy of aggressive Communist expansion” (in the opening words of NSC 13/2), and emphasized that in relaxing the earlier focus on reform “private enterprise should be encouraged.” Even while endorsing this vision of a bipolar world pitting capitalism against communism, however, these late-1940s policy makers never came close to embracing the shrink-the-government, privilege-the-private-sector, eliminate-all-barriers-to-foreign-trade-and-investment ideology that had become gospel by the time of the Iraq war. On the contrary, the new agendas of anticommunist economic assistance enlisted the expertise of professionals who usually supported interventionist policies of the sort associated with Keynesian theories and the New Deal, and who consequently tolerated and even encouraged what later free-market fundamentalists would denounce as planned or mixed economies.

An important policy directive introduced in December 1948, two months after NSC 13/2 was adopted, thus emphasized the “urgency that the Supreme Commander require the Japanese Government immediately to put into effect a program of domestic economic stabilization, including measures leading to fiscal, monetary, price, and wage stability, and maximum production for export.” In putting this in play, occupation authorities collaborated with the Japanese government in promoting institutions, laws, and practices that became central to the industrial policy Japan rode to prosperity over the next several decades. These measures went beyond creation of the powerful Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) in 1949 and extended to the passage in 1949 and 1950 of legislation governing trade, foreign exchange, and foreign investment. This was accompanied by the institutionalization of pervasive extralegal bureaucratic practices that eventually became widely known as “administrative guidance” (gyosei shido).132

Creation of the Ministry of International Trade and Industry capped a striking development in Japan’s transition from war to peace. Beginning in the 1930s, central planning became a fixation of leaders intent on mobilizing the nation for “total war.” Consolidation of influence and authority followed in both the public and private sectors, with the military assuming ever greater control over the bureaucracy and top-level cabinet planning. Defeat and occupation eliminated the military establishment, but not the penetrating reach of centralized authority. Civilian ministries and agencies assumed greater autonomy than before, particularly where economic issues were involved—and, by both example and deliberate policy, U.S. occupation authorities strengthened such bureaucratic prestige and authority even further. MacArthur’s headquarters itself was the perfect model of a hierarchical command structure, and by operating indirectly through the Japanese government it bolstered the influence of Japan’s own bureaucrats. By contrast to the experienced administrators and technocrats who honed their skills in the war years and survived the passage through to peace unpurged, Japan’s postwar politicians were a motley and inexperienced crew.

MITI, inaugurated in conjunction with the so-called Dodge line—a severe “disinflation” policy orchestrated by the conservative Detroit banker Joseph Dodge—became the centerpiece in the new agenda of guiding the private sector toward export-oriented production. Its influence extended beyond control over imports and exports to include energy policy, patents and technology transfers, loans and subsidies, strategic allotment of critical resources to designated key sectors (beginning with coal, steel, shipbuilding, and electric power), transfers of capital, and promotion of higher value-added manufactures. MITI worked in close and not always amiable collaboration with the business community, and became the acknowledged master of the art of exerting influence by “administrative guidance”—that is, by recommendations and warnings backed up by powers of persuasion other than the law.

The political scientist Chalmers Johnson later famously described the industrial policy associated with MITI as a “plan-oriented market economy,” and postwar Japan itself as a “capitalist development state.” It was certainly a hybrid; but what is notable in retrospect, particularly when set against the privatization craze associated with market fundamentalism, is that it was American planners alongside sharp Japanese technocrats and businessmen—rather than some sort of peculiar “cultural” or “traditional” Japanese propensity—that established this as a rational model for promoting economic growth in the dire circumstances in which defeated Japan found itself.133

Combating Carpetbagging in an Earlier Time

Apart from serving as midwife to MITI and encouraging “administrative guidance,” U.S. occupation authorities also introduced legislation that reflected thinking antithetical to the CPA’s shock program aimed at opening Iraq’s economy to unrestricted foreign trade and investment. The Americans who helped plan Japan’s recovery endorsed protectionism as essential for moving toward meaningful “self-sufficiency.” Like the later nation builders in Iraq, their ultimate goal was to integrate Japan in a global capitalist system—but with careful attention to indigenous needs and morale, and not overnight.

Protectionism was grounded in two laws: the “Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Control Law” enacted in February 1949, and “Foreign Investment Law” passed the following year. Both laws rested on legislation dating back to the early 1930s, and both survived until 1979, when the former was substantially revised and the latter abolished. Passage of the exchange and trade law enabled Japan to resume private trade for the first time since the occupation began, and endorsed relatively free trade in principle while permitting a high level of government control in practice. A standard reference source on Japan notes that it was “ironic that these ‘reformed’ controls came to resemble the prewar system in its complexity, coverage, and effectiveness,” and then proceeds to summarize the rationale for this neatly: “Given the urgent task of recovery from World War II, the occupation authorities and the Japanese government felt it essential to regulate the flow and distribution of exports, imports, and foreign exchange. Every major resource was critically scarce, and the free market could hardly be relied upon to achieve an optimal allocation of resources for the reconstruction of the country.”134

Where foreign investment was concerned, the contrast to Iraq was striking in ways beyond simple protectionism as opposed to a “capitalist dream” of free and unfettered foreign access. There was no initial “open for business” euphoria as promoted by the CPA and private-sector entrepreneurs, no early “gold rush” frenzy to get in on investment opportunities. Unlike Iraq’s oil, there was nothing in the way of natural as opposed to human resources. On the contrary, Japan’s economic prospects appeared dismal at the time and provoked negligible interest in U.S. business circles. Officials like Under Secretary of the Army William H. Draper Jr., who traveled the chambers-of-commerce circuit in the United States trying to drum up interest in Japan once the reverse course began in 1948, met a tepid response; and even into the mid-1950s, architects of the Cold War U.S.-Japan relationship such as John Foster Dulles had no vision at all of Japan ever producing sophisticated manufactures that might be competitive in the United States or other Western markets.135

Many capital-starved Japanese firms were anxious to attract foreign investors at this time, and U.S. planners deemed it necessary to protect them against themselves, lest they sell out controlling interest for a fraction of their company’s worth. Robert Fearey, a State Department specialist on Japan, spelled out this reasoning in a little book about the new “second phase” of the occupation published in 1950. Investment in Japan required licensing by SCAP, Fearey explained, which took care to ensure that this involved only “projects which would improve Japan’s foreign exchange position or otherwise positively aid Japan’s economic rehabilitation.”

Investment in Japanese enterprises, Fearey went on, “was made subject to the further condition that the investment must include provision of additional assets for the enterprise in contradistinction to the mere purchase of stocks or securities from other investors. Even with observance of these conditions, the depressed prices for Japanese securities since the war have offered opportunities for acquisition of securities at prices so far below their actual worth as to require careful review of each transaction by SCAP and the Japanese Government to avoid carpetbagging.” While the Foreign Investment Law of 1950 was promulgated to facilitate an inflow of foreign capital and guarantee protection for such investments, it thus simultaneously permitted the government to control such investment by overseeing borrowing and prohibiting full or majority foreign ownership. Instead, the Japanese government and its American patrons promoted the purchase of foreign, and mostly American, technologies.136

Mixed Legacies in an Age of Forgetting 137

The mixed economy was not, of course, peculiar to Japan or to the mid-twentieth century or to countries struggling to recover from the ravages of a war that shattered most of the world outside the United States. The role of the state differed from place to place and time to time. It reflected both doctrinaire and pragmatic outlooks, as well as keen historical awareness of the destruction caused by private wealth and power left free to grind less powerful people and countries beneath its wheels.