Masculine Gender Identity in Jack

Benny’s Humor

Jack Benny’s radio comedy played with gender identity, continually blurring the boundaries of what were at the time very narrow definitions of masculinity and femininity and strictly divided models for appropriate gendered behavior in society. Benny’s humor complicated and questioned what scholar Carole Vance terms the “implicit cultural ideology of fixed sexual categories.”1 His character explored varieties of masculinity that ranged from demanding patriarchal employer to insufficiently virile heterosexual male, to assimilated Jew, and from a straight man with a predilection for cross-dressing to a person of indeterminate sexual identity who impishly performed with effeminate and homosexual mannerisms.

As Jack Benny’s radio character transformed from a self-deprecating but suave master of ceremonies into the “Fall Guy,” the unfortunate soul to whom ridiculous and frustrating incidents happened, he became the target of an increasing number of humorous insults lobbed at him by his cast members. The show’s narrative world expanded to incorporate Benny’s frustrated attempts to rule over his home and his workplace, his painfully awkward dealings with Hollywood celebrities, and his exasperating experiences with shop clerks, waitresses, railroad station ticket sellers, and cab drivers. In the process of devising ever more ways in which Benny’s character could be vexed and scoffed at, his writers seized on nearly every possible way to belittle his masculine identity as an employer, a celebrity, and a heterosexual male. At times this escalated in the postwar years. While the move to television, during an era of hardening ideals of appropriate gender roles, brought new scrutiny of visual displays of identity, Jack appeared on TV as a nattily dressed, handsome, upper-middle-class man who looked years younger than his age. Despite losing the imaginative radio wordplay with which his cast could describe his lack of heterosexual physique and mannerisms, Benny and his writers in the visual arena of TV still occasionally engaged boundary-questioning humor, particularly in 1952 and 1954 episodes featuring Jack’s uncannily accurate impersonation of comedienne Gracie Allen.

Benny’s representations of masculinity have been the focus of academic inquiries (by McFadden, Doty, Balcerzak, and others) who have explored an archeology of possibilities for queer representation embedded in historical mainstream media. They have made insightful analysis of how Benny’s character can be read across a variety of audience interpretations.2 Their studies have detailed Jack’s comic involvement in homosocial relationships and his failures of heterosexual prowess. His effeminate characteristics and humorous suggestions of homosexual activities could have been enjoyed by some listeners in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, while they could have been abhorred by others, and understood by many as just another way to demonstrate Jack’s failure as a heterosexual patriarch. At the same time, Jack’s slyly incorporated outré sexual references possibly sailed right many some listeners’ heads, while they were acknowledged and enjoyed by some, and shocked and angered others.

The masculine gender identity of Jack’s character contained complexities and contradictions. Sometimes he made jokes that played with expressing gay preferences, other times he stood up for a heterosexual patriarchal authority to which his wealth and fame gave gives him access, and sometimes he titillated the audience with mentions of his enjoyment of feminine ways of behaving.3 Jack could more often be characterized as lacking in sexual desire or energy, rather than filled with sexual drive, more often asexual than overtly homosexual or heterosexual. Instead of focusing only on one moment, an examination of the complications inherent in gender identity that encompasses the breadth of Benny’s radio career over thirty years can help further explain Benny’s popularity with audiences across the sexual-political spectrum. It will also gain Benny even greater credit for his fearlessness, self-confidence, and wit.

Representations of female identity in radio and television have garnered the lion’s share of feminist analysis, as media scholar Rebecca Feasey notes, because these mediums were consumer oriented and geared to female viewers, or otherwise feminized.4 However, “masculinity and male heterosexuality continued to be understood as fixed, stable, unalterable and therefore beyond inquiry.”5 As Judith Butler and other scholars have argued, gender is not biologically innate but is performative and culturally created, and there have always been many types, varieties, alternatives, and levels of masculinity that men and women can perform. When Jack Benny created his comedy in mid-twentieth-century U.S. culture, the dominant stereotypes of masculine identity were narrow, and the differences between men and women were considered to be extremely wide.

Feasey suggests that popular culture provided models of gendered identity that formed “a hierarchy of acceptable, unacceptable and marginalized models for the male,”6 with a hegemonic masculinity as the desired ideal. “The hegemonic male was said to be a strong, successful, capable and authoritative man who derives his reputation from the workplace and his self-esteem from the public sphere,” writes Feasey.7 Even though very few people might reach it, it was a standard measuring stick “to which men are supposed to aspire.” Some lived in tension with it (such as minorities and “effeminate men”) and thus “command[ed] less power,” but most were, as Michael Kimmel says, “still complicit in sustaining this hierarchic model.”8 The Benny show narrative explored how the immutable, fixed categories of proper masculinity could crack to reveal possibilities of multiple forms of masculinity. While in other areas of popular culture, boundaries of gender representation were hardening, on Benny’s program, they were continually blurred.9

How did Benny’s gender-themed humor over the airwaves make up for limitations of listeners not being able to see the visual cues that constructed gender identities? On radio, as scholar Lori Kendall similarly suggests of computer-mediated online discussions, “the bodies of others may remain hidden and inaccessible, but this if anything gives references to such bodies even more social importance.”10 Gender characteristics of disembodied radio voices could be fluid and uncertain; hints were given by the tone and pitch of the performers’ voices. From Mary’s throaty laugh to Mrs. Day’s intimidating growl to Frank Nelson’s snideness, performers’ voices on the Benny show played with stereotypes. Benny and his radio writers also lavished attention in scripted dialogue on visible gender differences. To fill in the spaces of listeners’ imaginations, Benny show dialogue often described what the characters were wearing, especially if it was different from heterosexual, white middle-class norms. After his appearance in the film Charley’s Aunt (20th Century Fox, 1941), Jack’s adventures in cross-dressing costumes were added to the radio show, and the Benny gang joked about what Jack looked like in female clothing, or how he did not fill out the shoulders of his suits. Jack ribbed Phil Harris and Rochester about the loudly colored jackets they wore that aligned them with zoot suit culture. Mary and Jack made merciless fun of the overalls Babe wore to work on her construction jobs. Explorations of gender identity, and humor based on upending listeners’ expectations of how male and female characters would look and behave, was central to Jack Benny’s comedy.

FRUSTRATED WORKPLACE PATRIARCH

Jack’s character was at its most hegemonically masculine in his role as the star and producer of his radio show, and employer of his cast members at work and of Rochester at his home. Jack became depicted over the years as a demanding and churlish boss, traditionally patriarchal, paying his workers little, and trying to squeeze much work from them. He criticized Don’s weight, Phil’s drunkenness, the band’s lack of musical ability and slovenly habits, and Dennis’s craziness and stupidity (earlier, it was Kenny Baker’s craziness and stupidity). He attempted to fire the Sportsmen Quartet numerous times. His one retort to Mary’s insults was to threaten to send her back to work at the May Company department store. “The Mean Old Man,” a parody radio soap opera referenced on the show, took Benny as its model of a heartless landlord.

The insults swapped back and forth between Benny and his employees fit the traditions of workplace comedy, especially of the humor made in male-dominated factories and workshops. As Susan Douglas argues, radio comedy’s insult humor established a pecking order, and reminded the workers that Benny was the paternalistic boss.11 But the employees nearly always gave back worse than they got. Benny once explained the sources of comedy on the program from the point of view of an employer: “The humor of Phil Harris is, how can a man that is supposed to be working for me go on getting drunk, chasing women, insulting me, and still I don’t fire him? The humor of Rochester is—how can he get away with it? If Rochester and I share a bedroom on a Pullman he rushes in first and grabs the lower, and I have to sleep in the upper berth.”12

For all his petty power in the radio studio and at home, Jack nevertheless was terrified of his own bosses. Jack quaked in his boots every year when it came time for the sponsor to pick up the show’s option. From the earliest episodes in which Jack made outrageous ads for Canada Dry and wondered if his sponsor would fire him, Jack’s fear of his sponsor continued throughout his years on the radio. The sponsor was rarely an executive visiting the studio, but more often an unheard voice on the other end of a telephone, whom Jack begged for another chance (helplessly remonstrating against the sponsor’s unheard accusations “But . . . but . . . but . . . but!”)

While the stereotypical male authority figure was expected to remain in control of rationality and reason, keeping his emotions in check, Jack frequently lost his temper and yelled at annoying underlings—especially the Sportsmen Quartet, who often spun out of control while singing the program’s middle commercials. Benny and his writers orchestrated Jack’s “slow burn” build ups of infuriated responses (“Wait a minute . . . wait a minute! . . .WAIT A MINUTE!” and “Now cut that out!”) into crescendos of yelling voices, demonstrating that his leadership was always on the verge of collapsing into chaos.

Race as well as gender entered the picture of employer–employee relations in Jack’s management of Rochester. Jack as the employer of a household servant was a despot. He not only paid Rochester next to nothing but constantly ordered his servant to perform mountains of labor. Rochester could complain but could not say “no.” In the earliest years, Rochester was supposedly lazy and even stole from his employer. As Benny and the writers removed those stereotypes to make the character less offensive to African American critics, Rochester became a bit more feminized, a very diligent and selfless employee, despite his miniscule income. Jack could order Rochester to do anything, such as to spend all night searching for a lost golf ball. Despite how much Jack abused him, Rochester never considered quitting. The frustration of Rochester’s impossible work situation would inspire a violently imagined conclusion in Amiri Baraka’s short play “JELLO” (1970).13 To the credit of Anderson, Benny, and the show writers, although Rochester the housekeeper was stuck obeying Jack’s imperious demands, Rochester’s ability to talk back to Jack and to criticize him through humorous putdowns of the boss’s cheapness, vanity, and lack of virility created the sharpest humor on the radio program.

To add another deflating comic twist on Jack’s patriarchal authority, Benny’s writers began to make Jack parsimonious, unwilling to play his proper role in consumer culture. Accusing someone else of being cheap had a very long history; it was a staple of Italian commedia dell’arte conflicts between the employer and his servants, and vaudeville routines poking endless fun at thrifty Scotsmen. Jack eventually became rich as a prominent radio star, and he had money in every bank in town, plus a massively fortified vault in his basement, but he was increasingly loathe to spend a dime. As Mary commented in a 1950 pre-Christmas episode, whenever Jack went out to purchase something, there was trouble.14 He was the nation’s worst consumer. The clerks always gave him grief, and Jack balked at the price of everything. Frank Nelson confronted him everywhere as a belittling department store floorwalker or obstreperous railroad station ticket seller. Mel Blanc, as a department store clerk, was annually driven to insanity by Jack’s impossible demands made while purchasing the cheapest possible Christmas present for Don Wilson.

The blurring of real-life persona and fictional character in Jack Benny’s quest for patriarchal authority on his radio program occurred, most fascinatingly, in those fleeting moments live on the air in which Benny the performer let it slip that he indeed was the exacting director of his own show. Although Benny had a very limited ability to ad lib in response to other people’s jokes in real life, while in the middle of a radio broadcast, he was lightning fast to complain about a flubbed line of dialogue, or a missed ring of a telephone sound effect. He made sharp, cutting, fabulous ad libs that took the miscreants to task. Cast members hooted with delight the few times they caught the boss himself botching a line. Her microphone-fright increasing after the war, Mary began making more mistakes in reading her dialogue lines. As wide a berth as Jack otherwise took in criticizing her in their dialogue, when Mary flubbed a line, Jack immediately leapt on these mistakes and barked at her, to terrific comic effect. Those moments were the one time he could really “punish” her and put her in her place, to make up for all the insults she tossed at him.

The Jack Benny–Fred Allen radio feud of 1937 drew its spirit from the traditions of insult talk that are a central part of male interaction in workplaces and social situations. From gangs of boys who learn to fight as “play,” to Shakespearian insults hurled by gifted actors at one another, exchanges of ritualized insults in many cultures have enabled the players to duel, establish pecking order, show off their skills, and form mutual bonds with the audiences that cheered them on. Scholar Elijah Wald quotes jazz musician Mezz Mezzrow linking the African-American tradition of “the dozens” to an improvised jazz performance:

The idea right smack in the middle of every cat’s mind all the time was this: he had to sharpen his wits every way he could, make himself smarter and keener, better able to handle himself, more “hip.” . . . On the Corner the idea of a kind of mutual needling held sway, each guy spurring the other guy on to think faster and be more nimble-witted.15

Communal events like a contest of the dozens could hold a variety of meanings, suggests Wald. “One person’s bitter insult was another’s comic masterpiece, and what one observer interpreted as predatory bullying another might interpret as the fascinating survival” of old traditions.16 Women could toss the insults, but traditionally this has been a masculine endeavor (which undoubtedly added to the sting of Mary’s insults of Jack, as a woman was not supposed to be as adept at this game as men). The insults themselves needed to be wildly exaggerated, their absurdity providing the insurance that it would not be personally hurtful, but also making them humorous. While philosopher Jerome Neu suggests that too-truthful personal insults could result in the opponent swinging punches, if the insultee launched a reciprocal insult back in return, the incident became a game. Neu argues that insult games are ways of claiming superiority. They are all about asserting masculinity and cultural identity, claiming honor and defining the self, in shows of verbal and intellectual skill and dexterity.17

After the ten-week Benny-Allen feud climaxed in a hugely promoted meeting in a Manhattan ball room on March 14, 1937, instead of ending, the conflict continued and took on a life of its own. Fan magazine Radio Mirror published an adapted script of “The Mighty Benny-Allen Feud” in July 1938, and fans wrote to say that they had reenacted the skit as a party game.18 GIs on the battlefronts of World War II greeted Benny’s USO appearances with signs that said “Welcome, Fred Allen.” When Allen appeared as a guest on the erudite radio quiz sho, Information Please, host Clifton Fadiman focused mostly on jokes about how much Allen must hate Benny.

After the war, Benny continued the fun in several radio episodes with “Benny’s Boulevard,” sketches in which he parodied Allen’s Alley, with a clothespin affixed to his nose.19 In others, Benny and Allen swapped tall tales of their earliest encounters backstage on the hinterlands vaudeville circuit. These sketches were opportunities to mix playful boasting, insults, and accusations of plagiarizing each other’s acts with delightful reminiscences about acts like Fink’s Mules and Japanese flash acrobats (jugglers who tossed wooden barrels with their feet), which gave Fred and Jack the chance to work the word “bunghole” into the script.

Usually acerbic radio critic Harriet Van Horne commended Benny and Allen on the extended feud in 1947:

By professing to hate each other they have instigated more humorous situations and basked in more free publicity than any other would be haters in show business. By this time you might think that the situation was arid of humor. That neither could find in the other a single attribute to insult. But no. Mr. Benny finds new terms of derision for Allen’s program and the bags under his eyes. Fred, on his part, had endless variations on the theme of Jack’s stinginess, stupidity, conceit and clumsiness with the violin.20

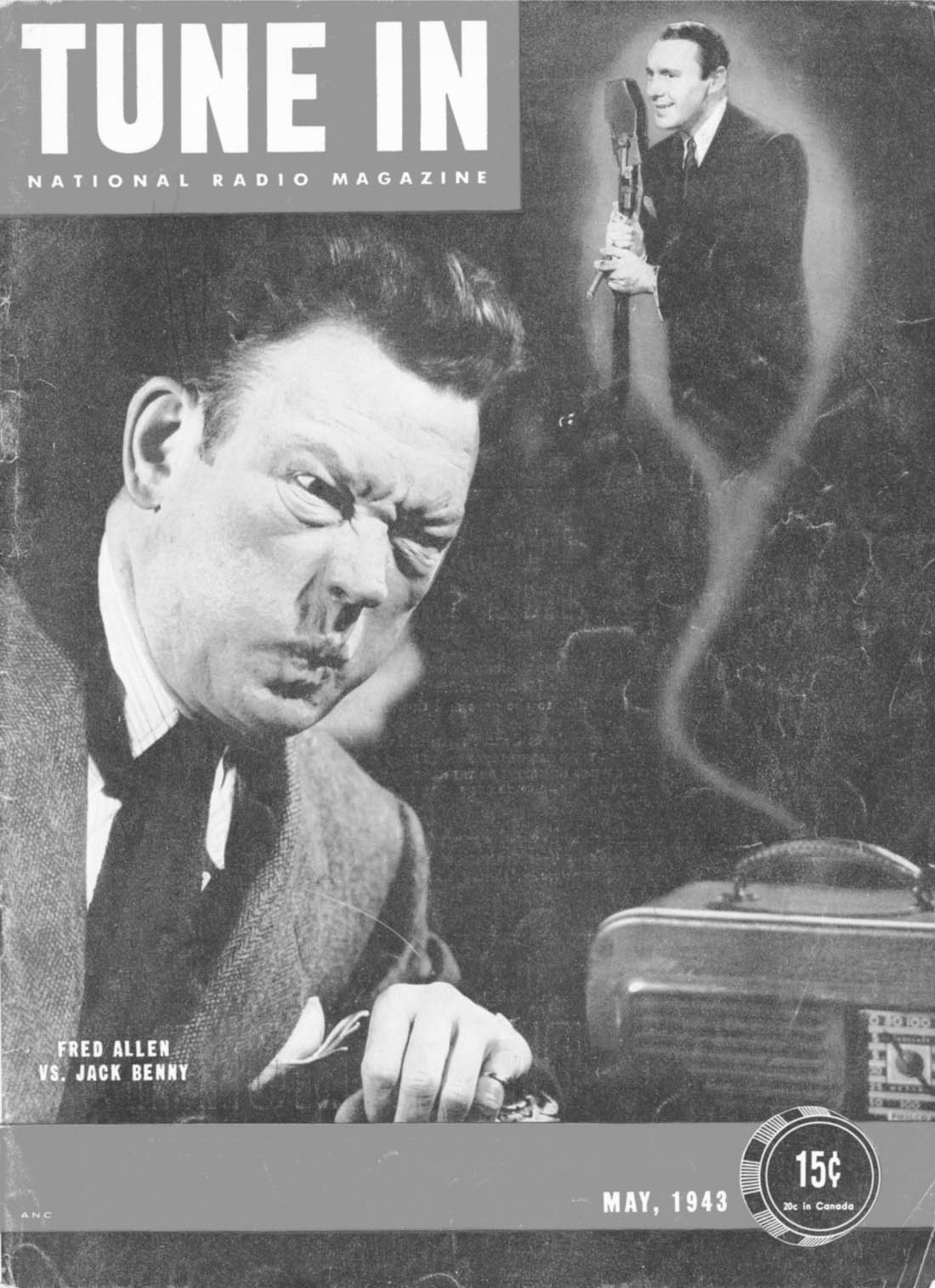

FIGURE 7. Fred Allen and Jack Benny cleverly extended their feud long after its 1937 beginnings. Here in 1943, Fred reacts to the supposed rotten smell of Jack’s poor jokes. Tune In, May 1943. Author’s collection.

A classic feud exchange occurred that year in live performance onstage at a New York City movie theater, as Variety’s review noted:

Jack Benny, according to Fred Allen during the historic tete-a-tete during Benny’s opening show at the Roxy, killed vaudeville 15 years ago, and now has returned to the scene of his crime . . . The Allen intrusion was one of the historic moments in vaudeville, wherein two top radio personalities on a friendly feuding basis had a chance to exchange insults. . . . Allen started the business by demanding a refund on his admission. After all, he argued, it was guaranteed that he’d die laughing, and inasmuch as he was still alive, he felt that he had his dough coming back. Benny argued that the Sportsmen should be worth 15 cents. Marjorie Reynolds was worth a quarter, and Rochester should be worth 20 cents. There was some disagreement on Phil Harris’ value, and after an initial demand of 10 cents, price was pared down two cents lower. They tossed for the balance, with Benny winning, and Benny shielded a dime for personal expenses.21

Critic John Crosby recalled another escapade as the feud’s best example of Allen’s triumphant, insulting wit. “Once Benny was appearing on the Paramount stage and Allen sat in the front row and fueled one witty insult after another at his old friend. After one quip, Benny, nonplussed, waved a twenty dollar bill at the audience and offered it to anyone who could top Allen’s last gag. Instantly Allen was on his feet, topped his own gag with a better one, and walked up and claimed the twenty dollars.”22

BENNY AND JEWISH MALE IDENTITY

To what extent was Jack Benny identified by audiences and critics as a Jewish male comic? Benny did not want to be pinned down to one stringently defined identity. “The humor of my program is this,” Benny explained in a 1948 interview, “I’m a big shot, see? I’m fast talking. I’m a smart guy. I’m boasting about how marvelous I am. I’m a marvelous lover. I’m a marvelous fiddle player. Then, five minutes after I start shooting off my mouth, my cast makes a shmo out of me.”23 “Shmo,” noted Leo Rosten, in The Joys of Yiddish, was a Yiddish term coined in America that meant idiot or cuckold, a lighter form of the more pejorative term “schmuck.” A shmo was a dull, stupid, obnoxious, or boring person, a shnook, a schlemiel, a hapless, clumsy, unlucky jerk who was the butt of other people’s jokes.24 Benny internally defined his character in terms of Jewish humor, but put him in an outwardly assimilationist package.

Benny’s complex relationship with Jewish identity, as explored by numerous scholars, seemed dependent on his listeners’ point of view and how they wished to define the man and his comedy. To mainstream Christian radio listeners, Benny presented himself as a highly assimilated Jew. Unlike some other performers from immigrant backgrounds, he did not speak with an ethnic accent or dress in ethnic costumes, and he used almost no Yiddish phrases in his work. Throughout his radio career, his shows celebrated Christmas and Easter as well as Mother’s Day and Halloween, but never touched on Jewish religious holidays.25 Radio listeners occasionally wrote into fan magazines to ask if Benny was indeed Jewish. To some commentators, however, Benny seemed to hide his ethnic identity to the point where it had disappeared.26

Early in his career, Benjamin Kubelsky (like hundreds of other first- and second-generation ethnic performers) changed his birth name to a stage moniker that sounded slicker and more assimilated, first Ben K. Benny, then (when bandleader Ben Bernie objected to the similarity) to Jack Benny. Holly Pearse suggests that Benny’s early years, spent in his hometown of Waukegan, Illinois, a small manufacturing city of 10,000–20,000 people an hour north of Chicago, assisted him in the adoption of an assimilated personality. Instead of being raised in the densely populated Lower East Side of New York City, with its extensive Jewish immigrant communities and rich culture (the backgrounds of Eddie Cantor, George Jessel, and George Burns), there were relatively few Jews in Waukegan. Benjamin Kubelsky learned the flat Midwestern accent shared by his schoolmates.27 As an adult, Benny was apparently not an actively religious person, rarely attending services. His faith was important to him—he married a Jewish woman, he contributed generously to Jewish charities, and he socialized in large part with other Jewish-heritage performers—but it remained a private aspect of his life.

Within the American Jewish community, Jack Benny was acclaimed as a beloved and prominent member of the faith, although certainly not as Jewish-identified to the extent of Eddie Cantor, who made his religious and ethnic identity a central part of his performing identity.28 Benny garnered only a modicum of coverage in the Jewish press over the years, but he cropped up occasionally, such as when an Atlanta-based publication celebrated him in 1948 with a full-page photograph captioned “America’s Greatest Jewish Comedian.” Benny figures prominently in most studies of Jewish performers in American entertainment history, as a prime exemplar of a second-generation immigrant who became prominent in mainstream American popular culture.29 His comic themes and performance style drew on many themes that scholars have typed as Jewish—the self-deprecating humor, the miserliness, the slight stature, the personality of the hapless “schmo,” the violin playing, the effeminate mannerisms.30

Stephen Whitfield characterizes nineteenth-century American humor as “cocksure patrimony”; “frontier humor exalted those who exhibited mastery, those who triumphed over rivals or enemies, those who demonstrated can-do supremacy.” On the other hand, Whitfield notes that Jewish humor centered on “self-deprecation and victimization.” “Jews continued to exhibit a proclivity for humor that underscored failure rather than success, marginality rather than influence and puniness rather than power,” he writes. Whitfield finds Jewish humor in twentieth-century American culture in the character of the antihero who was “self-mocking” and “exposed his own weakness,” and thus he judged Jack Benny to be the comedian to be the most associated with Jewish cultural themes.31

Other scholars have argued, however, that self-deprecating humor is common among many ethnic/marginalized groups, and that it’s not exclusively a Jewish trait.32 Benny was very sensitive about anti-Semitic slurs made against him in public that might damage his career (as exemplified by the horrid examples collected by the FBI at the time of his smuggling prosecution in 1939).33 Racial hatred was also his biggest concern about undertaking of the “I Can’t Stand Jack Benny” contest in late 1945, when he was careful to employ readers to remove any entries that spouted prejudiced attitudes. The identity blurring that Jack Benny was able to accomplish was to appear outwardly to look and sound very assimilated into American culture, but to draw on his Jewish cultural framework for his humor.

Despite Benny’s assimilationist tendencies for his own comic persona, his radio program did include occasional appearances of Jewish-identified characters. In the early 1930s, Harry Conn created a Jewish comic character who became a semifrequent visitor to the Benny radio program—Shlepperman, played by Sam Hearn. Shlepperman was an urban trickster, popping up when he was least expected, announcing himself with, “Hello, Strangzyer.” Shlepperman had a thick Yiddish accent. He was sharp with retorts but otherwise a pleasant fellow. Conn utilized the Shlepperman character as part of his collection of ethnic voices inserted into the end of a skit’s dialogue to surprise listeners. After the Benny show permanently relocated to the West Coast, Shlepperman appeared much less frequently. Hearn himself milked his Shlepperman role for years on the East Coast, putting on performances in theaters and clubs where he would portray the wily character, conversing with a recording of Benny, or telling Benny-related anecdotes.

When the new group of writers joined the Benny program in 1943, they experimented with adding new characters, such as Herman Peabody, the timid insurance salesman; bombastic Belly Laugh Barton, the writer; and brash Steve Bradley, the public relations agent. Mr. Kitzel first appeared on January 6, 1946, when Jack and the gang attended the Rose Bowl football game, and they encountered a funny little man with a Yiddish-inflected voice, selling hotdogs up in the stands. Kitzel was played by Artie Auerbach, a radio actor and photographer. Both Kitzel’s jingle (“Pickle in the middle and the mustard on top!”) and his character were popular with radio listeners. The writers began bringing him back regularly onto the radio show. If Shlepperman had darted in and out of Benny’s program with an urbanized vibe, Mr. Kitzel instead was a gentle greenhorn. Kitzel’s humor rose from his “cultural incompetence” in Michele Hilmes’s term, his confusion and lack of knowledge of American society. Kitzel substituted Jewish names for Anglo-Saxon-named celebrities, events, and objects. His tentative voice and reaction to Jack’s comments, a surprised “hoo hoo HOO,” marked him as an unassimilated immigrant. Fred Allen’s character Pansy Nussbaum made similar types of remarks when she appeared in “Allen’s Alley” skits. Cantor had the Greek Parkykarkas and “Mad Russian” characters on his radio program, and Mrs. Nussbaum was joined in Allen’s Alley by a Yankee farmer, Southern senator, and a drunken Irish lout. Benny, like the other comics, distanced himself from these ethnic personalities by his smooth, superior use of language. There was debate within the Jewish entertainment community in the late 1940s and 1950s as to whether continuation of these broadly stereotyped Jewish ethnic characters like Kitzel stimulated prejudice against the Jewish American community; performers like Sam Levenson argued for ending them.34 Benny incorporated Kitzel into nearly 120 of his radio program episodes in the late 1940s and 1950s. Kitzel also made an appearance on Benny’s first TV episode, and thereafter the character was still used occasionally, until Auerbach’s death in 1957. Kitzel’s numerous radio appearances added to many of the continuing themes of Jack’s humor meant that reminders of Jewish ethnic identity remained embedded around the edges of Benny’s radio program.

BENNY’S FEMALE IMPERSONATIONS

In Benny’s mid- to late-1930s radio episodes, Jack occasionally requested that his male cast members take female roles in their movie parodies. Their skits drew on the long tradition of male crossdressing in comic stage performances, which had been popular with mainstream entertainment audiences for hundreds of years.35 When the Benny group did a takeoff of the film Girls’ Dormitory (20th Century Fox, 1936), the male cast members made titillating jokes while complaining about having to dress as characters of the opposite sex. Words like “girdles” and “stockings” were worked into the dialogue to add visual humor to the audience’s imagining of the scene. On other occasions they performed skits about a football team or the all-male crew of a submarine, and Mary got to grumble about having to wear shoulder pads and threatened to add lace to her uniforms.

The most prominent occasion of group cross-dressing on the Benny radio show in the 1930s occurred when Jack and the cast performed a parody of the film The Women (MGM, 1939). The film’s publicity had highlighted how unusual it was to have an entirely female cast. Benny and his players performed a wickedly funny sketch, with Jack preening at the opportunity to play Norma Shearer, and Eddie Anderson grouching about having to wear mascara as the maid. Jack, Don, Phil, and Dennis had a high time playing gossipy society women complaining about the faithless men in their lives, while Mary introduced the play’s acts with meowing side-comments. The skit was so popular that the cast was asked to reprise it several times at entertainment industry functions in Hollywood.

Historical case studies of the sexual naiveté and resistance of the 1930s American movie-going public, especially in smaller towns, who when encountering older men in relationships with Shirley Temple in Shirley’s films either could not conceptualize or angrily rejected the possibility of pedophilic inferences, are small but telling examples demonstrating the power of dominant heterosexual ideology. Heterosexual ideology was so strong at midcentury that many people were incredulous about alternative sexual identities or desires, and many were unable to speak of, imagine, or acknowledge them. Others actively refused to.36 Media scholar Karin Quimby has suggested that “straight” audiences could use the concept of “disavowal” to downplay any homosexual content in popular media and understand the program’s humor as being within a normative heterosexual content. Other audience members might understand the scene to represent both straight and gay connotations. Disavowal, Quimby writes, “allows some audience members both to acknowledge gay male difference . . . and to disavow this difference through the heterosexual fantasy” that sees the characters, like themselves, as straight. Quimby argues that this openness of interpretations in media audiences’ reception dynamic allows such programs “to attract and keep audiences who may be somewhat uncomfortable.” Quimby argues that the “dynamic of contradiction or disavowal” can be built into the program’s narrative, through storylines, the visual look or sound of performers, and their understated acting to make them seem as “acceptable” or noncontroversial to straight audiences as possible.37 Benny’s programs, like those of other radio comics, played with outré, unusual, or forbidden sexual humor in this way. In radio performances, dialogue and descriptive language created imaginative worlds that listeners could configure to their own pleasures. Suggestive euphemisms were easier to slyly bypass unsophisticated audiences, although infamous encounters such as Mae West with Charlie McCarthy on the Bergen and McCarthy radio program in 1937 could draw wide criticism and reaction.38

“Male-to-female transvestitism is a complex phenomenon that is often confused with other manifestations of male-to-female cross-dressing, e.g. drag performance,” argues feminist scholar Samantha Allen.39 She notes that although studies have shown that as much as 87 percent of people who wear clothes of another gender identify as heterosexual, it has been widely assumed in American and Western culture that this is a sign of homosexuality. A sharp historical gender divide of clothing and behavior has mandated that “the clothes one wears must match one’s felt sex which must be opposite to the sex one desires.”40 Men have had a variety of reasons over the years for wishing to wear female clothing, both erotic and performative. They have taken pleasure in confusing or shocking the gender-identity distinctions of those who view men in dresses, or a pleasure in performing or inhabiting female identity.

Sexual-themed humor was prominent in radio comedy, as it had been in vaudeville and the stage. Matthew Murray, in his study on radio censorship, argues that radio networks were fully cognizant of its popularity and potency as a ratings-getter and selling tool. Like the interplay between movie producers and the film industry’s censorship organization, radio network administrators attempted to negotiate the tensions between material that titillated some audiences and offended others, and material that reflected “modern” values as well as the maintenance of conservative values of propriety. In 1934, NBC established a Continuity Acceptance Department, headed by Janet MacRorie, to scrutinize the scripts of material that sponsors intended to broadcast over their airwaves.41 Comedians, with their penchant to joke about the forbidden, gave these radio censors headaches. Fred Allen earned their frequent ire over the years for his allusions to barnyard bathroom humor (chickens straining to lay eggs, cows with unruly udders). Eddie Cantor, Bob Hope, Charlie McCarthy/Edgar Bergen, Ed Wynn, Red Skelton, Jack Pearl—all the comics gave the censors trouble at one point or another with questionable humor. Radio authorities did not seek to completely remove instances and themes of transgressive sexuality, but to contain and tame it. They sought to reincorporate taboo topics as much as possible into norms of white middle-class culture and standards of appropriate male and female representation and behavior.42

Not only did Benny’s radio program play with male cross-dressing, but the show likewise occasionally incorporated situations and jokes that could to some listeners be perceived as having gay, queer, or effeminate connotations. Some listeners chuckled at the outré comedy, while conservative straight audiences could explain away the dangerous ideas in this humor as being nonoffensive, a foolish parody of normative heterosexual ideologies. During the May 29, 1938, episode, which took place at Paramount Studios, Jack ordered Rochester to read Joan Bennett’s lines as Jack practiced a love scene for his upcoming film appearance in Artists and Models Abroad (Paramount, 1938). Don, Mary, and Phil listened in from outside the dressing room while the two rehearsed. Jack complained that Rochester was not acting with sufficient emotion:

JACK: Rochester, you’re not giving me anything. How can I be romantic when you won’t put any feeling into your lines? I wish you’d get into the mood of it.

ROCHESTER: Mood? I did everything but kiss you! I started out driving your car, and now I’m your leading lady. . . . Are we on our honeymoon yet?

The lines were greeted with ready laughter from the studio audience. Radio listeners might have complained to the network or sponsor or their local stations, but there is no evidence in the trade papers or archives that this occurred. Because these sexually outré moments were created by Benny and his writers, and performed by his cast with sly humor, mainstream audiences could understand them as just absurdities, grotesque burlesques of behavior appropriate in other situations like movie love scenes. While historians such as George Chauncey have found evidence that gay male radio listeners in the 1930s understood the Benny show’s humor to incorporate homosexual-related humor that they found pleasurable, Benny’s program at the same time could be perceived by mainstream heterosexual listeners to be inoffensive to their ideological beliefs.43

Public reaction to Benny’s comic cross-dressing in radio and film and his flirtations with gay humor changed over time, from the 1930s to the mid-1950s. As Benny’s enjoyment of the roles and the humor he created remained the same, the media form he appeared in made a difference in critical reactions, and the culture kept changing around him. While some critics have interpreted these cross-dressing performances to strongly link Jack the character and Benny the person to homosexual identity, I believe that Benny found pleasure in not choosing any particular identity, in keeping listeners, viewers, and critics titillated, confused, and guessing, wondering about how Jack was blurring the sharp distinctions between male and female behavior and heterosexual and homosexual identities through a variety of comically erotic ways of behaving.

From his start on-air in 1932, Jack Benny had been considered one of the network’s least problematic performers by the NBC Continuity Acceptance Department and the network executives who worried about complaints from offended listeners and special interest groups. Benny made one mild allusion to outré sexuality in an early program in his first three months on the radio, when he read out testimonials from animals at the zoo proclaiming their fondness for Canada Dry Ginger Ale. It was an excuse for terrible puns. Mr. and Mrs. Leopard claimed that Canada Dry “hit the right spot,” and the mountain lion was glad that the soda was sold at all “mountains.” Then Jack reported from the Monkey House, “Dear Mr. Benny, your Canada Dry Ginger Ale is very good. I love it with a dash of orchid ice cream. Signed Jim Pansy.” Benny slyly commented, “Ahh, they even have them in the zoo!” This association of the forbidden with the product, along with Benny’s other outrageous humorous in-program commercials for Canada Dry, led his sponsor to demand that he choose much less controversial paths in which to advertise their ginger ale.

Archival records of NBC’s Continuity Acceptance Department are only partial and can’t provide definitive answers about which radio programs or performers caused them the most concerns. Several documents mention Benny’s program, but network executives usually were quick to note that complaints about his show were rare.44 Listeners who wished to voice complaints about Benny’s show might also have directed their comments to the sponsor or to the advertising agency that produced it. Here too, unfortunately, archival evidence is very scarce, leaving historians with just a few tantalizing clues about censorship problems that the Benny program encountered.

In January 1937, NBC vice president Bertha Brainard complained to West Coast NBC executive John Swallow about her frustration over the network’s lack of control over radio performers when their programs originated from Hollywood, far from the New York–based Continuity Acceptance Department’s oversight:

I listened to the Jack Benny program last night and think there are perhaps certain things which you, in your diplomatic fashion, can suggest to Jack. The line “I think you are nuts” I have never felt belonged in Mr. Benny’s copy. He has always been above reproach and this phrase we have found to be disapproved by a large percentage of our audience. I felt that there was a definite tendency toward effeminate characterizations, particularly by Frank Parker. I feel strongly about this, especially when a tenor with a high voice has the line. I’d like to see anything of the lavender nature all out. Jack doesn’t need this sort of material to get his humor.45

It was the popular tenor, Parker, not Benny, who was giving hints of sexual transgression in his performance, and Parker did it through his delivery (as his written dialogue had been approved by NBC authorities). The only other significant objection about possible homosexual inferences in the Benny program in the archived Continuity Acceptance Department files was a complaint about “effeminate men” lodged about the Benny show in 1939.46 In March 1942 NBC executives had lengthy discussions about their problems with risqué jokes being told on nearly all the comedians’ programs—Allen, Benny, Cantor, Gracie Allen, Skelton. The worst offender, they claimed, was Bob Hope. Network executives were receiving little help from sponsors or ad agencies in toning down the raucous humor, which in Hope’s case was becoming such an issue that several Midwestern stations threatened to band together and refuse to carry his program. These relatively few complaints about offensive humor in Benny’s show were all that appeared to exist in the records in the archival NBC radio collections.47

BENNY PLAYS CHARLEY’S AUNT

Following a successful 1940 Broadway revival of Thomas Brandon’s 1892 frequently performed slapstick, the cross-dressing farce Charley’s Aunt (which had featured a young Jose Ferrer in his first starring role), in August 1941 the 20th Century Fox film studio released a film adaptation, starring Benny. Set at Oxford University in the 1890s, the play’s slight narrative concerned two male undergraduates who convince a third (Fancourt Babberly, played by Benny) to pose as a wealthy old lady, Charley’s Brazilian Aunt Donna Lucia, to chaperone visits of the boys’ girlfriends to their rooms. Complications ensued when Babberly, dressed as the aunt (in long Victorian crinolines and a grey wig), attracted the interest of all the old men on campus, from doddering professors and the girls’ crusty uncle to his classmate’s father. The men were mostly attracted by the aunt’s wealth, but the old professors also appeared to romantically desire the old woman. Pratfalls and rump-kicking abounded, and then pretty Kay Francis (the real aunt) arrived. Eventually the truth of the identity of Charley’s aunt is revealed, the young couples are united, and Babberly falls in love with the “real” aunt.

Fox’s publicity campaign for the film focused on Benny’s gender boundary crossing, featuring tag lines such as “She is the funniest thing in skirts! And most important of all—she is a HE!”48 Broad physical slapstick and cigar chomping were emphasized in photographic and cartooned advertising illustrations to reassure conservatives that nothing about Benny or his performance was actually effeminate. Nearly all newspaper reviews of the film concurred in finding that the film was hilarious simply because Benny wore female clothing. Many delighted in detailing Benny’s costume, underclothes, and wigs. The Chicago Times noted:

Benny makes a very pretty picture indeed as he peeks coyly out from behind a black lace fan, as he toys with the white silk fichu around his neck. Flutters his eyelashes and tosses his curls—a poor copy of Whistler’s mother. His awkwardness in skirts, his coy simpering and mad efforts to escape from a pair of romantic gentlemen who both yearn to make him a bride, provide the picture with considerable hilarity.49

A small number of conservative reviewers claimed to be offended by the film. Family Circle Magazine’s reviewer wrote: “Everybody at the theater laughed fit to bust. Made me feel like an outsider. But I’m the killjoy at the party who doesn’t go into gales when Joe puts on Mabel’s hat.”50 The Albany (New York) Knickerbocker noted,” Now this critic, while no prude, confesses that he has never been able to detect the slighted gleam of humor in such a masquerade of the sexes. . . . There is something fundamentally vulgar about it. But the dear public eats it up.”51 Other reviewers reassured potential moviegoers that the film was purely heterosexual fun, with no exhibition of alternative sexual connotations. The Los Angeles Herald Express reported, “[Benny] plays the part without swish and in almost his natural voice.”52 Howard Barnes of New York Herald Tribune wrote: “He has the wisdom to play the famous part straight. There is never a question of effeminacy in his portrayal. That, I think, makes the difference between an uproarious redaction of the Thomas farce or a dull museum piece.”53 The Los Angeles Times calmed readers’ qualms by claiming that the Babberley character “loathes the masquerade that he has to put over, but the young men, his associates, have him on the rope.”54 On the other hand, for the New York Post reviewer, Benny’s own effeminate tendencies particularly suited him to the part: “As for Jack Benny, his long established screen and radio character, somewhat lacking in the more virile traits, fits snugly into the demands of an aunt role.”55

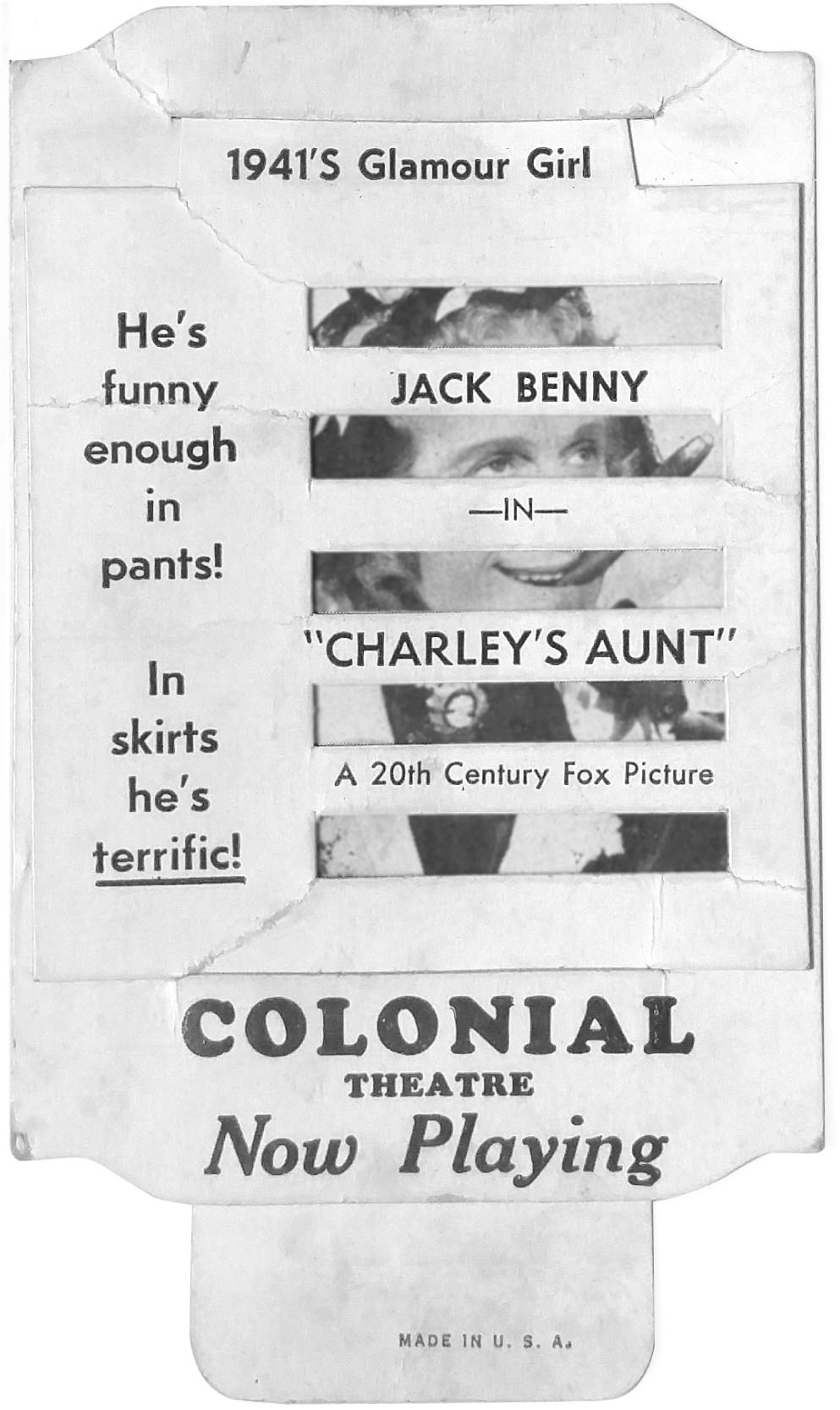

FIGURES 8 AND 9. The humor of Jack Benny’s 1941 film adaptation of the old farce Charley’s Aunt was promoted by local theaters as the surprise of a man dressed in women’s clothing. Colonial Theater (location unknown) souvenir, 1941. Author’s collection.

A few reviewers, nonplussed by the sharp loudness of audience laughter in response to the film, connected its popularity to rampantly accelerating war fears. The New York Morning Telegraph mused over the riotous reaction at the film’s premiere at the Roxy: “There’s no explaining it, no more than there was any explaining the astonishing success of the José Ferrer stage version that took Broadway by storm last Winter. Maybe it has something to do with the current state of the public mind, bordering close on hysteria anyway, maybe it has something to do with the weather.”56 Another paper termed it “a blitzkrieg of furious fun, wordy humor and deep belly laughs.”57

At the Academy Awards ceremony, held in Hollywood in March 1942, Bob Hope presented Jack Benny with a faux award, to “honor” Benny for portraying “the best sweater girl on the screen.” It was a gold-toned Oscar-like statuette, dressed in long skirt and tiny grey wig, with a cigar in its mouth, and was dubbed “Oscarine.”58 The publicity this joke garnered in newspapers and fan magazines demonstrated the growing cultural anxiety over the instability of traditional gender roles. Benny himself quipped:

I should have won the Academy Award for my acting in Charley’s Aunt. But the voters were baffled. In that picture I played the part of a man and the part of a woman. I was exceptional in both parts, but the voters didn’t know whether to elect me best actor or best actress. I don’t know whether to be jealous of Gary Cooper or Joan Fontaine.59

Once or twice a season, during the ensuring wartime years, Benny and his writers incorporated mentions of cross-dressing and sexually outré behavior into Benny’s radio routines. In October 1942 Jack and Rochester were in the kitchen putting up Mother Benny’s Apple Butter to sell. Both wore aprons, and visiting cast member Dennis Day asked, “Why are you wearing dresses?” On the October 24, 1943, show, Jack joked about sharing a train sleeping berth with Don Wilson and Dennis Day. Train travel during wartime was overcrowded, so most listeners found humor in that context of shared inconvenience. Jack’s character was thoroughly defined by his cheapness by this point, so others laughed at the misery caused by Jack refusing to book separate accommodations. Still others might be amused to imagine the corpulent Wilson crammed into the small space with Jack and Dennis. But the suggestion that three men were sleeping together was available to titillate some listeners with a sexual connotation.

On the October 8, 1944, episode, Jack told Mary a story about wearing his Charley’s Aunt dress to enter the Palladium dance hall (a place where men had to pay double the admission price of women). Penurious Jack claimed it was accidental that he’d just left the film set of Charley’s Aunt in costume, and he used it to get in at half price:

JACK: Mary, I’m not dressing up like a girl again. I’ll never forget what happened last time. . . . hmmm. A guy buys you a drink, he thinks he OWNS you.

JACK: (in a girlish voice) What I went through . . .

MARY: (laughs) Jack, Jack it was bad enough being dressed like a girl to get in, but you didn’t have to let a fellow buy you a drink.60

JACK: well for goodness sake Mary I danced with him all evening, I deserved SOMETHING. What a rotten dancer he was . . . Say, Mary, I wonder what he’d have thought if he knew who I really was, especially when he tried to put his arm around me?

MARY: He tried to put his arm around you? Well gosh Jack, why didn’t you tell him?

JACK: I didn’t have the heart to, he was a Marine and he was going overseas in the morning.

Network radio programs in the 1940s and 1950s usually depicted the occasional gay character in stereotypical ways, as weaklings with high voices and nervous temperaments. These characters were generally greeted with “horror, laughter, pity or disgust from a mainstream heterosexual audience,” as Feasey notes of later 1960s TV episodes. Straight characters were free to make derogatory jokes about homosexuals—it was considered “entertaining” and appropriate to marginalize them. Feasey notes that homosexuality was still presented for comic value fifty years later on the TV series Friends (NBC, 1994–2004) when its main characters became upset and felt humiliated at being mistaken for gay or encountering gayness. At mid-twentieth century as well as for the rest of the era, most straight white men expressed a great deal of uneasiness around being associated in any way with issues of homosexuality. Thus, it’s all the more remarkable that, on the Benny radio program in the 1940s and early 1950s, while the jokes about cross-dressing, effeminate behavior, and sleeping arrangements were meant to insult and humiliate the characters (mostly Jack), there was no gay bashing or malice shown toward characters who hinted at outré sexual identities. On the program, there was tacit acceptance of “less than” or “different than” heterosexual ideals. Most radio audiences of the day did not outright reject these characters and situations. There were no public boycotts of programs. Mainstream audiences probably assumed that these were the harmless quirks of absurd characters.61

On the Benny radio program, although Mary and Phil constantly insulted Jack about his lack of masculinity, they did not do it with disgust. His activities were presented as just a facet of his character of the schlemiel. Jack’s body was regularly criticized, and sometimes instead of making pronouncements about his weak, thin, or old appearance, the cast members joked about his womanly physique—especially his shapely legs and feminine walk. Jack joined in this humor, explaining the circumstances, and not embarrassed but accepting of his own body and sartorial choices.62 Jack was presented most frequently as asexual or neutered and very rarely as expressing sexual desire. It is likely that most audience members of the day considered Jack harmless. Mary once claimed that embracing Jack was like kissing a dead fish.63

In the late 1940s, the occasions of outré sexual innuendo occasionally rose on Benny’s radio program, even as public attitudes toward appropriate expression of gender identity were hardening. On occasion, however, Benny and his writers took chances and pushed the edge of the acceptability envelope. One of the program’s most outlandish radio program skits based around cross-dressing and sexual desire involved someone other than Jack doing the costumed play, as Jack took a familiar role as the “Fall Guy” who was the victim of the practical joke. At the opening of the radio show on November 2, 1947, Don, Jack, and Mary discussed their past weekend activities:

JACK: I had a lot of fun Friday night, too, Don. You know I went to a Halloween party in Beverly Hills, and I met the most wonderful girl, and she was so cute, you know she came dressed up as Little Bo Peep. . . . Kids, I got to tell you about this girl, she wore a little black mask that seemed to . . . oh I don’t know . . . she was just wonderful . . . I really went nuts about her.

MARY: Well, I’ve never heard you talk like this before.

JACK: I can’t help it . . .when she came through the door, I looked at her, and she looked at me, and I could just feel something run up and down my spine.

[Dennis enters the conversation, and after his usual distractions, he informs Jack that Phil Harris had also attended the party.]

JACK: Phil was there? Gee that’s funny, I didn’t see him. What was he dressed as?

DENNIS: Little Bo Peep.

JACK: Little Bo Peep? . . . Phil!!!

PHIL: Kiss me, Pumpkins!

JACK: No, no wonder he wouldn’t take off his mask.

MARY: Phil, you mean Jack danced with you all evening?

PHIL: Not only that, Livvy, he asked if he could drive me home.

MARY: No!

PHIL: Yeah. Say Livvy, have you ever seen the lights of the city from Mulholland Drive?

JACK: I can’t understand it, how could he shave so close?

MARY: Phil, I think you carried it too far, why didn’t you tell Jack who you were?

PHIL: What, and spoil an old man’s evening?

JACK: Alright Phil, look, you’ve had your joke, now let’s forget it.

PHIL: Forget it? I want those nylons you promised me, Alice could use them.

JACK: Look, you’re not getting those nylons and I’m not putting you in pictures either. Now look we’ve got a show to do.

PHIL: Look Jackson, come here a minute, [takes Jack aside, in low tones] I want to ask you something.

JACK: What is it?

PHIL: (whispers) Come here I want to ask you something. . . . Do my eyes still twinkle like two stars in the summer sky?

JACK: (loudly) Oh boy, do you fall for everything you hear! I really put one over on you, bud! (lower) But I still don’t understand how he could shave so close.

In the recording of the live broadcast of this episode, there were an extraordinary thirteen seconds of studio audience laughter and applause caused by Dennis’s revealing of Phil as being Bo Peep. The loud laughter seems a little more nervous and edgy than usual. Benny, his writers and cast members were perfectly aware of what they were doing in playing with possibly sexually suggestive, queer humor. Writer Milt Josefsberg recalled the times the scriptwriters would put really outrageous jokes into the script just to draw the wrath of the network censors, to distract them from the more slyly subtle joke that got slipped in elsewhere.

In the postwar era of increasingly conservative public attitudes toward appropriate heterosexual gender roles and rising unease, fear, and policing of homosexuality, some media critics, upholding virile masculine standards, disdained the Benny’s shows hints of titillating homosexual humor. John Crosby of the New York Herald Tribune commented in February 1948:

One of the stock characters in radio comedy is what might charitably be described as the male spinster. He is the man who says “Mr. Berle, we are not amused!” He’s the postal inspector on the Dennis Day show who said “Mr. Day, I LOVE you!” He’s the man who sells Jack Benny the ticket to Cukamonga [sic]. . . . He is waspish, supercilious, sarcastic, vaguely effeminate, and he lives in a state of perpetual irritation. He usually occupies a position of minor authority and uses it tyrannically. Invariably he appears when the comedian wants comedy badly and is in a hurry. He gets a sure-fire laugh from the studio audience not for what he says but for how he says it and, in spite of their affection, I’m damn tired of him and I’m sure a great many others are, too.64

Crosby, like the NBC Continuity Acceptance Department administrators thirteen years before, claimed that most inferences of homosexuality came from minor characters on the Jack Benny program, such as Frank Nelson in his “nasty man” roles. Although Crosby’s description could have fit Jack to a significant degree, there may possibly have been repercussions in the industry had Crosby gone so far as to label such a big star as homosexual. I have not yet uncovered a significant number of other public criticisms of Benny radio episodes for their aberrant sexual humor. This perhaps implies that the majority of radio listeners assumed that Benny’s shows were unproblematic family fare. Either radio audiences did not notice these examples that hinted of alternative sexual identities, or they found these characters simply absurd. Certainly other groups were listening closely, such as the African American listeners and critics who paid very close attention to Rochester’s role on the program, but this sexual innuendo did not seem to draw much comment. Given the paucity of complaints in the archives, the increased amount of sexually titillating humor on the Benny radio program in the early 1950s is fascinating to examine. The scandal magazines of the late 1940s and 1950s, like Confidential, would have a field day exploiting photos of Benny in his Gracie Allen costume as purported evidence of his outré sexual behavior. As we will see in the chapter addressing Benny’s challenges of moving his radio program to television, TV critics and TV audiences would begin to complain about the visuality and intrusion of sexual images broadcast into the home. Wouldn’t those concerns and conservative cultural values have created a greater amount of criticism of Benny’s occasional blue humor on the radio airwaves than we have been able yet to find? The imaginative aspects of the unseen radio medium must have allowed for greater latitude for audiences not to complain about things that they heard, that would have upset them had they seen them.

BENNY IMPERSONATES GRACIE ALLEN

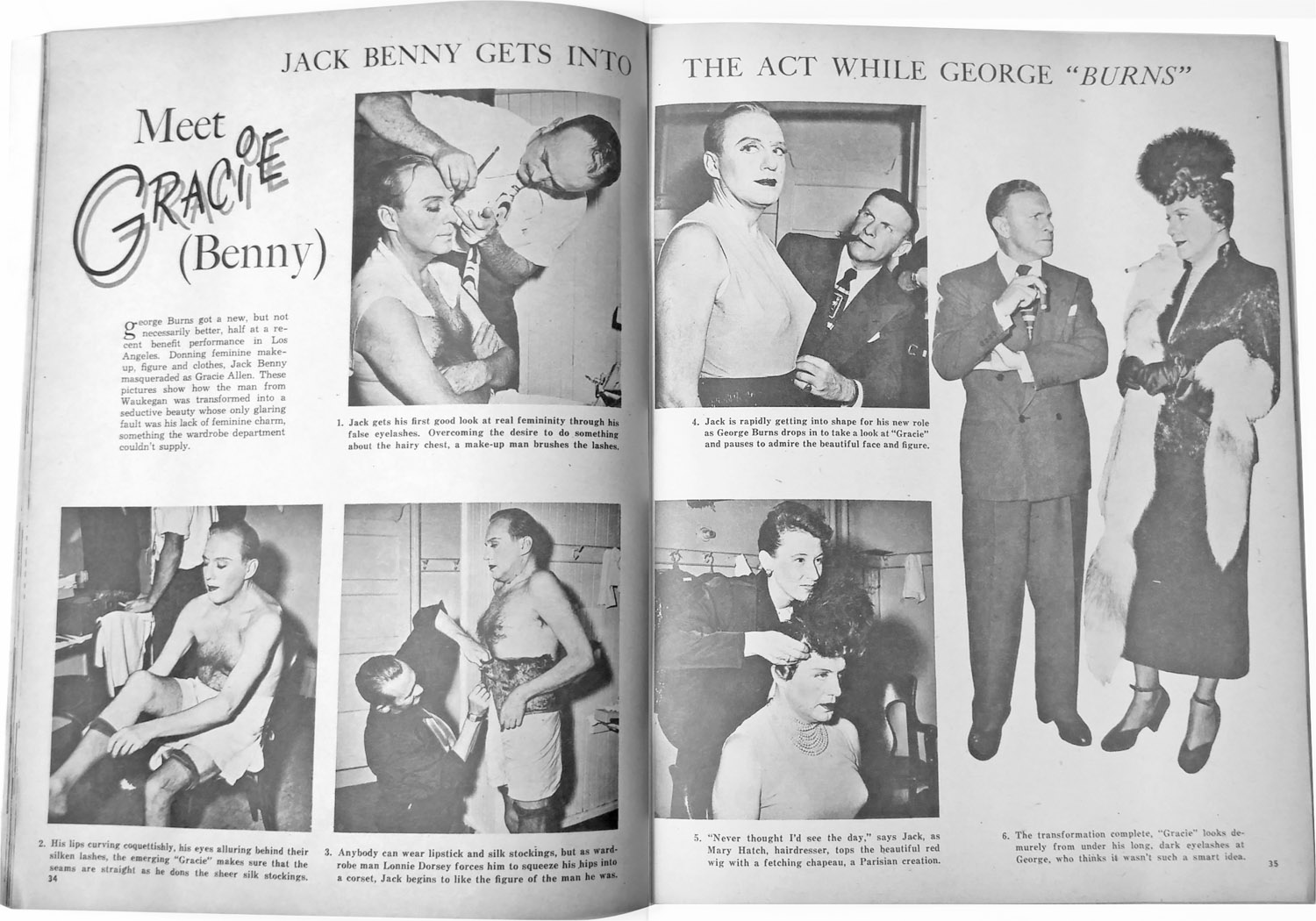

The pleasure in cross-dressing that Jack Benny took, over the years, found its finest expression in his imitation of Gracie Allen. Jack created the Gracie impersonation for a private, members-only West Coast Friars Club charity fundraising entertainment, probably in 1949, perhaps earlier. The Friars programs (as they had traditionally been done in New York) featured only male performers, while women were invited to be part of the audience. In the 1948 Friar’s Frolic program, Danny Kaye impersonated modern dancer Kay Thompson, with Benny, George Burns, Jack Carson, and Van Johnson performing as “her” evening-suited back up dancers, the Williams Boys. In April 1949, the Los Angeles Times reported that “the girls numbers” were a big success.65 The highlight of both 1949 versions of the Friar’s Frolic show in Los Angeles was Benny and Burns. Benny did a full-on impersonation of Gracie Allen, not a broad burlesque performance, but one paying careful attention to get the costume and behavior as close to the original as possible. The Benny-Burns skit was reported fairly widely in the American press, accompanied by as many or more slyly titillating comments and details as had greeted Benny’s performance as Charley’s Aunt eight years previously. Fan magazine Radio and Television Best ran a two-page photo spread, “Meet Gracie (Benny)” detailing Jack’s transformation with makeup, false eyelashes and lipstick, silk stockings, corset, curly wig, and feathered hat.66

FIGURE 10. Even before Benny performed his Gracie Allen routine on television, fan magazines were obsessed with reporting the details with which Benny transformed himself for private stage performance with women’s clothing and makeup. Radio Best, October 1949, 34–35. Author’s collection.

Benny was of course only one of several noted comics doing female impersonations on American television in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Milton Berle had donned outlandish female costumes (Cleopatra, Carmen Miranda) as part of his slapstick vaudeville-style performances on his program. Eddie Cantor and Ken Murray (whose comedy TV show was sponsored, like Benny’s, by the American Tobacco Company) appeared in broad, campy, exaggerated kind of drag performance. Benny, on the other hand, created something that delighted some audience members by being so slyly accurate. As one TV reviewer claimed, “Unlike Berle and Cantor, Benny made a handsome, rather than a grotesque woman. Showed a mighty neat ankle, too.”67

In 1950 and 1951, Benny and Burns repeated their routine at private parties. In March 1952, Benny and his writers crafted a TV show episode to highlight the Gracie routine, expanding the ten-minute skit with a surrounding story about Gracie’s disappearance from the guest-starring role she and George Burns were to play on the Benny TV program. In the first half of the TV episode, Jack was hidden behind a backstage dressing room screen as he parried the insults hurled by George, Rochester, Don, and Frank Nelson, the makeup man. Jack also struggled with his makeup, girdle, and other accoutrements necessary to impersonate Gracie. The middle portion of the Benny TV episode displayed the onstage Burns and “Gracie Benny” performance. It was drawn from old Burns and Allen vaudeville routines from the 1920s, and Benny’s sly impression of Gracie’s expressions, movements, and tone of voice were spot-on. Benny’s entrance onstage was greeted with great deal of audience applause, and the intimacy of the television production’s close-up shots emphasized the costume and make-up he wore. In the conclusion, after the stage show, Benny was shown sitting in his dressing room sans wig but still in costume and makeup. The real Gracie Allen burst into the room, mistook Jack for a hussy named Tallulah, and slapped him, then vented her wrath about cheating husbands by slapping every man she subsequently encountered (including Jack’s sponsor).

Benny’s Gracie Allen impersonation aimed for cross-dressing verisimilitude—his costume was subdued and accurate, not an exaggerated clown or drag outfit. The careful attention to seamed stockings, high heels, gloves, and hat, and Benny’s reserved channeling of Gracie’s mannerisms and ways of speaking were uncannily close and unnerving to some critics and conservatives in this time of increasingly sharp divisions between appropriate male and female behavior. Reaction to Benny’s March 9 TV episode was swift and loud. Variety’s Jack Hellman reported that “In all his 42 years in the business, says Jack Benny, no show of his occasioned as much comment as his recent TV’er in which he played Gracie Allen. What surprised most of the lookers was his studied trick of playing it straight without any ludicrous trimmings.”68 A network executive at CBS gathered the next morning’s most important reviews and telegraphed them to Benny’s manager Irving Fein in Hollywood.69 One was scathing—Ben Gross of the New York Daily News titled his response “Not so Funny”:

Maybe there’s something wrong with my sense of humor, but I’m one of those odd guys who just can’t see anything screamingly funny in a man masquerading as a woman—except in “Charlie’s Aunt,” of course—well the highlight of Jack Benny’s show on CBS TV at 7:30 last night was Jack pretending to be Gracie Allen, teamed up with George Burns. For the first few moments the act produced a few faint laughs on my part, although it wowed the studio audience. After that, I thought it all to be a deadly bore.70

On the other hand, Harriet Van Horne of the New York World Telegram announced “Benny Panics ‘Em in Sequins and Furs,” judging that “Poor Jack” had finally created a visually oriented show that overcame the limitations of his aurally based radio humor:

[When Gracie went missing,] Jack stepped into the breach, wearing a sequin-trimmed dress, platinum fox furs, a plumed hat and high heeled shoes. His foundation garment, it was made elaborately clear, is borrowed from the rotund announcer, Don Wilson. When Burns and Benny made their entrance there was a roar of laughter. Everything stopped while the audience luxuriated in the delicious lunacy of Jack Benny playing Gracie Allen. It was the most spectacular “entrance” I’ve ever seen on television.71

These critics demonstrated the deeply divided responses to Benny’s episode.72 Jack Gould of the New York Times’s enthusiastic praise exposed the nervous tension that surrounded Benny’s cross-dressing gamble:

Jack’s success came in a form which nine times out of ten spells disaster for the clowns of Broadway and Hollywood: he did a feminine characterization. But this was an impersonation that avoided the clichés to which Milton Berle in particular is addicted—the smeared lipstick, the padded figure and the affected lisp—and instead was essentially a masterly tidbit of hilarious pantomime. . . . [W]hat made the show was Mr. Benny’s walk. He took mincing little steps that in themselves were almost a satirical ballet on all the grand dames that ever lived. Without saying a word he would shrug a shoulder, pat the back of his coiffure or lift an eyebrow. Each gesture was underplayed and disciplined. Yet cumulatively they provided the idea framework for Jack’s mastery of deadpan comedy.73

Quite a few TV reviewers’ responses were negative. One noted: “I can understand the bit [Benny’s Gracie routine] at a gathering of show folk, but on a coast to coast telecast I thought it ill-advised, in questionable taste and to no particular advantage. In other words, a broad, burlesque impersonation is one thing but a slick, near-perfect job of the sort that Benny did last night is quite another and much too close for comfort.”74 Andy Wilson in the Detroit Times asked, “Without getting into a long winded discussion with psychiatrists and amateur mind-readers: why do comedians think putting on women’s clothing is funny anymore? Probably the main reason is that some one is sure to snicker at the comedian’s legs and feet and then you get an epidemic of laughs.”75 Reviewers for the Washington Star and Kansas City Star claimed that this kind of humor was “beneath” Benny and that they cringed “when men dress up as women for laughs.” They declared that it was not appropriate for family viewing.76 The reviews expressed a theme that “proper middle class family values” were being challenged in these TV shows, visually displaying too much sexual innuendo, working-class burlesque, and “poor taste” invading their living rooms in the new technology.77

Emboldened by the attention it garnered when broadcast live to a small national audience in 1952, Jack Benny seized the opportunity to repeat this sketch in a filmed television episode broadcast to a far larger audience on April 11, 1954. Variety’s review acknowledged that that it still pulled a massive reaction from studio audiences, with Benny’s entrance in costume generating one of the “longest laughs of the season.”78 Nevertheless among the reviews there were still a significant percentage of negative responses, noting the reviewers’ discomfort with the drag performance, a Boston reviewer calling it a “lowly device of female impersonation.”79 The Hollywood Reporter acknowledged the sketch’s popularity but questioned its appropriateness:

Benny . . . was an impressive female worthy of wolf whistles anywhere. The material was good too and Burns and Benny dancing between jokes was high style stuff. They’ll be talking about this show in the trade for many a moon. And what they’re saying is—“Should Benny get his laughs this way?”80

Jack continued to reference cross-dressing humor in 1954, claiming in his next television episode (May 2, 1954) that he was picked up by a sailor while wearing his Gracie Allen costume, and in another sketch in fall 1954 set at Jack’s house, after losing a bet at cards to Rochester, Jack wore an apron while cleaning his kitchen, and Don entered the scene and mistook him for a woman.81 Subsequently, however, Benny and his writers chose to pull back from further direct presentations or discussions of female cross-dressing in his television programs. They adhered more often to a situation comedy formula in realistic domestic, neighborhood, and studio settings, with Jack playing nothing more outré than a fastidious fussbudget. Milton Berle and the other vaudeville-influenced comics on television were toning down their burlesque-flavored comedy of crazy drag costumes and over-the-top physical comedy. Cultural taboos on appropriate representations of gender and sexuality were hardening. The new celebrity scandal magazines like Confidential and Uncensored ran photographs of Benny in Gracie Allen makeup and spun rumors about his sexuality. As the nation’s culture grew more skittish in the mid-1950s about portrayals of outré gender identity, and Benny himself aged, the space for Benny to create playful aural and visual humor about gender identity closed down. That doesn’t mean it disappeared. Jack was comfortable to keep blurring the lines when he could, such as on talk show appearances in the early 1970s. On occasion he would make self-deprecating jokes about how other comics criticized him for his womanly walk, and then gladly demonstrate it.

FIGURE 11. The new celebrity scandal magazines seized on images of Jack Benny in makeup for his Gracie Allen impersonation as headline-worthy outré sexual behavior to exploit. Uncensored, November 1955. Author’s collection.

• • •

Humorous comments on American constructions of masculinity gender and sexual identity were central to Jack Benny’s humor, throughout his career. These examples, stretching across Benny’s radio, film, and early TV performances from 1932 to 1954 have shown the slippery nature of the way that he played with masculine gender identity, and his humor’s continuities and changes over two decades. His jokes and comic characterization blurred the boundaries of sharply defined categories that became more strictly enforced in American popular culture over time. The humor of his roles was available to be read in many ways by a variety of audiences in his era and today. Reception of Benny’s comedy had a wide range of meanings—it could confirm conservative assumptions about heterosexuality and male dominance, and it could create spaces for alternative conceptions of masculinity and religious and ethnic identity. It could open a place for the recognition and acceptance of queerness. By being so adept at blurring the distinct categories of gendered behavior, Benny’s comedy created a liminal space in which men and women, Jews and Gentiles, straights and gays, could safely laugh at their differences and similarities.

The next two chapters examine the career of African American actor Eddie Anderson and the construction of racial identity that Anderson, portraying Jack Benny’s radio valet Rochester, brought to Benny’s radio narrative. Although the Rochester character only joined the Benny program in 1938, he rapidly became one of the most crucial components of the show’s humor, and endured the longest as the most effective counterpoint to Jack’s egotism, vanity, and frustrated efforts at patriarchal control. Anderson’s career, and Rochester’s radio characterization, would be impacted by racism and evolving cultural, political, and industrial limitations, opportunities, and pressures across the tumultuous period from Rochester’s introduction to the show to Anderson’s rise to public acclaim in both the mainstream white media and the African American press by 1940, to Rochester’s inclusion as a flash-point of debate over racial representation in the mass media in the wartime and postwar era.