Eddie Anderson, Rochester, and

Race in 1930s Radio and Film

African American actor Eddie Anderson achieved enormous popularity through his work on Jack Benny’s radio program, from his one-time appearance as a train porter on the radio show in March 1937 to a central role as Jack’s valet “Rochester” beginning in late December 1937 that continued on radio, in film, and on television for more than twenty-five years.1 Soon after his incorporation into the Benny program, the Rochester character became a hit with both white and black audiences, despite—and because of—racial attitudes of the day.2 Rochester’s witty retorts to the boss’s supercilious demands and egotistical vanities, croaked out in his distinctive, raspy voice, helped to keep the Benny program high in the ratings, made Anderson the most prominent black performer in broadcasting before 1960, and earned him an income of upwards of $150,000 per year.3

Success came at a high price for Eddie Anderson, however, for as an African American performer portraying a fictional character created by whites in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, he faced challenges of racial stereotyping, prejudice, and critique from all sides—from racist, rejecting white audiences in the South; conservative, skittish sponsors in New York; and the racially insensitive media industries in Hollywood to disdain from liberal critics, members of the black intelligentsia, and politically active, equality-seeking members of the younger generation of African Americans. Anderson was the only major black performer on primetime network radio. Everyone knew that Amos ’n’ Andy, the most famous program featuring black characters, was created and voiced mainly by whites. On other radio shows, the minor roles of African American characters were usually portrayed by white actors performing what historians have characterized as “verbal blackface.”4 The few black performers on network radio programs were usually required to use stereotypically uncultured language and accents. Given the intense, widespread racial prejudice during these decades (not only in the Jim Crow South, but across the nation), how did Anderson survive and succeed?

To avoid the “Uncle Tom” catcalls and harsh criticism that film performances by black actors like Stepin Fetchit and Willie Best provoked, Anderson constantly had to negotiate a path through this minefield of cultural, social, and political issues. Meanwhile, Anderson labored to be a top-flight comedian and entertainer, to please Jack Benny, to serve as a conscientious supporter of Southern California’s African American community, and to enjoy the fruits of his celebrity. Eddie Anderson stood in a precarious place, benefitting and being denigrated, being held up and held down, expected by many different constituencies to act “appropriately” when whatever was amenable to one group would anger the others.

In making his way through these ambivalent situations, Anderson merged his public identity into that of fictional character Rochester Van Jones. “Where Rochester leaves off and Eddie Anderson begins is often difficult for Eddie, himself, to tell,” the Baltimore Afro-American reported in 1945. “There are few radio personalities which so completely absorb the identity of their creator in the eyes of the public as that of the Rochester which he created for the Jack Benny show on NBC.”5 Yet, Anderson also began to face increasing criticism for silently acquiescing to (and complacently accepting, some charged) the demands of racially insensitive, white-controlled mass media industries. Another article from the Baltimore Afro-American in 1945 complained:

Some people are critical of the fact that Eddie Anderson, as Rochester, is a comedian, pure and simple. He commercializes the humor of many situations. He “refuses to propagandize” or use his influence—except for fun. In his own words, “a performer is a performer first and last. He has no business making propaganda. People want to be entertained, not educated.” He thinks that the things a colored performer does on the stage or radio have no serious bearing on the nature of race relations. He has no strong notions about “what ought to be done on the racial front.” Eddie Anderson, colored, is always Rochester, comedian.6

These two chapters explore the difficulties Eddie Anderson encountered, his achievements while enacting Rochester’s role, and the subsequent impact of this character on black and white popular culture in the radio era. This first chapter retraces Anderson’s early career in the 1920s and 1930s to understand the many challenges that black performers faced in vaudeville, film, and broadcasting. Then it examines Anderson’s first years on the Benny program, and how its writers constructed and contained the Rochester character. On the other hand, the Rochester character (through Anderson’s performance) broke through the restraints of stereotype to become an important voice of interracial understanding in popular culture. Benny’s radio show narrative struggled to juggle competing representations of Rochester as a comic star, an African American actor, a stereotyped servant character, and the most intelligent “stooge” among Jack’s underlings. Popular understanding of the Rochester character was impacted by cultural change—widely held racist stereotypes and prejudices were being challenged by agitation for racial equality. If network radio in the 1930s and 1940s held the potential to “transcend the visual,” as Michele Hilmes notes, the Benny show, nevertheless, like many others, “obsessively rehearsed” racial (and gender) distinctions to cue listeners to characters’ racial identity.7 She states that radio, “in speaking to us as a nation during a crucial period of time helped to shape our cultural consciousness and to define us as a people in ways that were certainly not unitary but cut deeply across individual, class, racial and ethnic experience.”8 Anderson’s radio character, however, also divided listeners into camps of those who enjoyed his jokes and were reassured of the rightness of the social order by Rochester’s complacency in his servant role, and those who were angry at the belittling stereotypes his position represented.

The representation of Rochester in his first years on Benny’s Jell-O Program (1937–1939) contained heavy doses of minstrel stereotypes—stealing, dice playing, being superstitious, an obsession with pork chops—but from the beginning these faults were also undercut by his rapier-sharp wit and collegial relationship with Jack. The show’s dialogue alternately showcased and contained Rochester in a dynamic relationship with the boss. The show’s early tendency to present him as inferior (thieving, carousing) and continuing focus on making his blackness “visible” on the radio made racial identity essential to Rochester’s character. It also isolated Rochester from the rest of the cast by assuming that everyone else was white and superior. On the other hand, when Rochester and Jack interacted, it was nearly always Jack who was wrong, inept, or foolish, and it was Rochester who had more knowledge and tried (even if in vain) to steer Jack toward a better path.

This chapter charts Anderson’s rise to intermedia fame through his appearance in several Benny films, and examines how his public persona was shaped in white and black media. It ends with Anderson’s greatest pinnacles of public achievement, when he was honored at an all-star film premiere in Harlem, awarded prestigious race relations awards, hailed as being a harbinger of a “new day” in interracial amity and new possibilities for black artistic, social, and economic achievement. The start of World War II only enhanced the possibilities for Anderson’s career. The next chapter, however, will show how the long shadow of Uncle Tom on the one hand, and increasingly obstinate white racism in some parts of American society on the other, increasingly dogged his career in the 1940s and 1950s.

EDDIE ANDERSON’S EARLY ENTERTAINMENT CAREER

Eddie Anderson left few traces of his life in archives, and revealed little in interviews with inquiring newspaper reporters and scholars. His reticence to speak about himself, his experiences, or his opinions on racial representation in American entertainment made it easy for critics to downplay his achievements.9 Anderson’s silence can be seen as a consequence of the ambivalent, difficult position in which he found his public life constructed. He was prominent in the West Coast African American community, but he was also beholden to Jack Benny and the Rochester role for his fame. Like other black actors struggling to make a living from Hollywood films and network radio, Anderson constantly had to maneuver, dodging between racist attitudes and pronouncements from white society on the one hand and Uncle Tom charges from black society on the other. Whenever possible, he remained in a silent, neutral position to avoid any controversy that would anger radio sponsors, film studio, Benny, or black critics and scuttle his career. What can be gleaned from coverage of Anderson in the black and white entertainment press shows him to have been a hard-working, versatile dancer, singer, and comic from humble but not totally impoverished beginnings, who reached a modicum of success across many years in vaudeville, night clubs, and film before a radio role made him a huge star—a story not unlike Jack Benny’s.

Edmund Lincoln Anderson Jr. was born in Oakland, California, on September 18, 1905, second-oldest of six children (four boys and two girls) of Edmund “Big Ed” and Ella Mae Anderson.10 “Big Ed,” who’d been born in Michigan in 1869, was a comedian and bass soloist who sang and performed with the Richards and Pringle Georgia Minstrels, Howe’s Greater London Circus, and Fordham’s medicine shows.11 Ella Mae (also known as Maude), born in 1881 and raised in Kansas, was one of the few African American circus tightrope walkers in the business, but she had to retire early after a crippling fall.12 They were part of the small West Coast black community, the family traveling with entertainment troupes before migrating to California sometime around the turn of the century.

Eddie’s older brother Cornelius was a dancer who had worked as a child along with his father in the Georgia Minstrels; his younger brothers and sisters were also sometime-performers. Eddie told stories of selling newspapers and peddling cordwood for three dollars a load on the streets of San Francisco as a young child. Most accounts credit his famous gravelly voice as the result of injuries sustained from shouting out the San Francisco Bulletin’s headlines.13 “We really hawked newspapers when I was a kid. We thought that the loudest voice sold the papers, which wasn’t true, of course. I ruptured my vocal cords from straining them.”14 Eddie claimed that his father had hoped he would be a singer, and lamented, “You’ve done gone an’ ruined your voice.”15 At age twelve Eddie was dancing and singing with his younger brother Lloyd in San Francisco hotel lobbies and at the Presidio military base for World War I soldiers.16 By thirteen, he traveled down to San Diego and back in the cast of movie cowboy Art Accord and Edith Sterling’s Wild West show.17 Anderson attended two years of high school in San Mateo; he worked odd jobs, delivering packages for a tailor and driving teams of horses on the Spreckels sugar plantation near San Francisco. The family relocated south to Los Angeles sometime in the 1920s.18

At fifteen, Eddie performed with his older brother Cornie in a two-man dancing and singing act, sometimes with the “Strut” Mitchell troupe.19 In the early 1920s they joined with a partner, Larry “Flying” Ford, to form an act they called the Three Black Aces. The earliest mention of Eddie (at age eighteen) in the Chicago Defender comes from a November 1923 review of a “midnight ramble” at the Dunbar Theater, located on Central Avenue, the hub of Los Angeles’s black community: “The bill was opened by Eddie Anderson who set the house on fire with his eccentric dancing. Naturally a favorite at this house, he started something that had the rest of the bill trying to see just who would walk away with the honors of the evening.”20 “I was mainly a dancer,” Eddie later told the Baltimore Afro-American, “but I always liked comedy. We used to finish off our dance with some comedy and it stuck.”21

Eddie’s most distinguishing characteristic was his unusual voice, a scratchy, octave-ranging sound that emanated from a compact, stocky body with an expressive face and dancer’s litheness. “Mr. Anderson’s voice was a challenge to describe,” noted his New York Times obituary:

It was most often associated with gravel, frequently with sandpaper, and was described variously as rasping, wheezing and scratchy, and in valiant journalist attempt, was likened to “a grinding rasp that sounds like a crosscut saw biting through a knot in a hardwood log.” Mr. Anderson, himself, noting that his natural voice was actually deeper than his performing voice, once described how he achieved the effect that became his trademark. “I pitch it up and put more pressure behind it to get that vibration” he said. “To me, I’m talking very high, but on the radio it resonates very deep.”22

Others described his distinctive voice as “possessing much of the same quality of a klaxon horn,” “a cross between a calliope and a buzz saw,” and “a cement-mixer.”23

In 1924 the Three Black Aces performed in Southern California night spots for white and black audiences, and played on the Pantages West Coast vaudeville circuit. In September 1924 they joined a sixty-five-member black stage review, performing at the Philharmonic Theater in Los Angeles. The Los Angeles Record reported “The dancing of Eddie Anderson, Cornie Anderson and Lawrence Ford as ‘Three Black Aces’ had in it the primeval spirit of syncopation, elemental, abandoned and whole hearted.”24 Ford left soon afterward, and the act regrouped as “Cabbage” and “Little Aesop” Anderson, the Two Black Aces.

The pair won a spot in another large, all-black stage review called Steppin’ High. The California Eagle characterized these roles as “chorus boy in an all sepia revue,” but it was professional show business and the Anderson brothers were undoubtedly glad to be in a major production, which featured Mamie Smith, one of the earliest female blues singers.25 Ambitiously embarking on a national tour,26 the Steppin’ High company ran into financial trouble in its fifteenth week, and folded that summer in Omaha, Nebraska. This ironically was a lucky break for Eddie and Cornie, as an admiring theatrical manager at Omaha’s World Theater got the stranded pair a spot, first on his own stage and then on the Pantages Midwestern vaudeville circuit that included theaters in Minneapolis and Kansas City.27 Eddie and Cornie remained in the Midwest, performing in and around Chicago for a year or two, including fifteen weeks at the Sunset Café with Cab Calloway,28 and at the State-Lake, Palace, and McVickers Theaters.29

Eventually the Andersons worked their way back to the West Coast, playing the Fanchon and Marco and Keith-Orpheum vaudeville circuits. Eddie performed at black nightspots on Central Avenue in Los Angeles, including the Apex Night Club, where Eddie headed the floor show with Duke Ellington’s band, and for several years at Frank Sebastian’s Cotton Club in Culver City (a chic nightspot that the Defender noted “caters exclusively to white trade”), dancing, singing, joking, and acting as the review’s master of ceremonies, with Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton, or Duke Ellington’s bands providing the music. He ran into repeated troubles with Sebastian for tardiness, occasionally had his pay docked, and eventually was fired.30 In April 1933 Eddie appeared in an Earl Dancer production, “Fourteen Gentlemen from Harlem,” with Etta Moton as featured singer, at the Warner Theater. In 1936 Eddie performed at the Club Alabam on Central Avenue, dancing with Johnny Taylor, performing what one colleague recalled as “zany comedy routines, including a slow motion, delayed action dance that convulsed audiences. A great sense of timing was theirs. . . . Both performers had tremendous talent. They revised, improvised as they went along. And audiences loved it.”31

Motion picture appearances were the goal of nearly every performer in Southern California, and when he returned west in 1932, Anderson joined other black performers making the rounds of Central Casting, hoping to get the occasional walk-on or extra part. His early film appearances include nine uncredited roles as a butler, porter, sailor, chauffeur, or bootblack. Eddie received a rare bit part large enough to get a screen credit, as a bum in Transient Lady (Universal, 1935). The Defender and Los Angeles Sentinel always reported with optimism on African American performers’ successes in obtaining these tiny roles, trying to create a sense of a film community in which blacks had significant impact.32 In 1936, Eddie landed a feature film part, as Noah, the third largest role, in the Warner Bros. film version of Marc Connelly’s stage success The Green Pastures. It garnered good reviews for Anderson, but did not propel him to further film advancement.33 That year he had uncredited bits in Show Boat (Universal, 1936), and in sixteen other films produced at the major studios. In 1937 Eddie had a dozen very small movie roles, working at studios from Warner Bros. to Paramount, Columbia, 20th Century Fox, and Republic.

Similar (on a smaller scale) to Jack Benny’s early professional journey of moving between entertainment forms, Eddie Anderson was piecing together a solid and busy, if relatively minor, entertainment career in Los Angeles. He was best known in the West Coast black community as a night club emcee, dancer, singer, and comic, at cabarets that catered to the African American community on Central Avenue and at others that attracted wealthy white pleasure-seekers. He appeared in regional-level vaudeville programs and movie theater stage prologues. He was known, but not prominent, in Chicago and New York entertainment circles. The Hollywood film studios kept his roles at miniscule size.

THE MARGINALITY OF AFRICAN AMERICANS IN RADIO

Ambitious to expand his career, thirty-two-year-old Eddie Anderson joined the casting call for a one-time bit role on Jack Benny’s highly rated NBC radio comedy program in March 1937. Primetime radio programs were relocating production to the West Coast from New York City. However, Eddie and the other auditioning black actors did not have reason to think the opportunities in network radio were going to be any better than in films. In fact, the situation for them was significantly worse. There were very few African American performers on network coast to coast shows—appearing only as orchestra musicians, church choir singers, or playing tiny roles as servants or minstrel-type buffoons.

Black actors Juano Hernandez and Frank Silvera occasionally got small parts in nonblack roles because they had built strong reputations as “competent linguists” who could perform other dialects.34 But a great many other black character roles, from Amos and Andy to servants and minstrel show participants, were performed by white voice actors. Like Gosden and Correll, and Marlin Hurt who would originate the role of Beulah the maid on the Great Gildersleeve radio program, voice actors might create up to a dozen different roles of various race, ethnic, and gender identities on a single program. Radio producers considered it a cost-saving measure, but the practice contributed to the marked lack of racial and ethnic diversity in American network broadcasting. Radio program producers too often sought easily identified foreign accents and vocal stereotypes, not the depth of variety of subtle accents, pronunciation, and vocal timbre. The technological limitations of radio vocal reproduction multiplied this use of stereotypical dialects and accents.

African American radio actors bitterly complained that radio producers and casting directors wanted the very few roles for blacks to sound stereotypically identifiable to whites, incorporating much more drawl than professional actors wanted to use.35 The few black performers who were able to audition for radio roles almost always had to compromise by creating vocal characterizations with accents drawn from minstrel shows and “coon song” performers on the vaudeville circuit. Actor Johnny Lee recalled, “I had to learn to speak Negro dialect when I first began acting. I had to learn to talk as white people believe Negroes talked. Most of the directors take it for granted that if you’re a Negro actor, you’ll do the part of a Negro automatically.36

Radio sponsors, their ad agencies, and the networks maintained for years that their fear of alienating white Southern consumer-listeners kept them from using black performers, similar to the “myth of the Southern box office” that film producers alluded to when they refused to create prominent movie roles for black actors. Radio sponsors claimed to be terrified that prejudiced white listeners would associate a black performer negatively with their products and refuse to buy.37 As well, although there were some European-ethnic radio stations broadcasting in the North, Jim Crow restrictions kept African American–operated radio stations from opening until after World War II.38

The black press protested for years, in vain, about the dearth of African American performers in prominent roles on the airwaves. Black newspapers, the NAACP, and social critics also had to fight hard to reduce and remove blatant racism from the network radio airwaves, as was exemplified by the controversy and threats of boycotts surrounding Will Rogers’s on-air repeated use of a racial slur when describing spirituals, comments made in a January 21, 1934, episode of his Good Gulf Oil program for which he subsequently was very reluctant to publically apologize.39

Nevertheless, optimists hoped that the absence of black performers on network radio could be ameliorated. In April 1937, two weeks after Eddie’s one-time appearance on the Benny program, the Louis Armstrong Orchestra variety program debuted on the NBC Blue network, Fridays at 9:00 P.M., sponsored by Fleishman’s Yeast.40 Hopes were high in the black community for its continuing success. Yet there were disappointments from the start. The Pittsburgh Courier complained that the opening program’s dialog (written by Southern white dialect novelist Octavus Roy Cohen) was “typical Uncle Tom Negro” fare and only a burlesque of how actual black people spoke.41 Armstrong forswore any use of the minstrel-type language, but conservative whites still objected to his jazz-musician-style vocabulary and the intonation of his voice. Despite a promise to relocate the program to Sunday evenings, the sponsor backed out and the Armstrong show was soon cancelled.

Meanwhile, the most famous “black” performers and characters on the radio were Amos and Andy, performed by white actors Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll. Melvin Ely, Michele Hilmes, and other scholars have explored the vast popularity, cultural impact, and many controversies surrounding the Amos ’n’ Andy show, which began broadcasting in its earliest form from Chicago in 1928 and became a huge hit for NBC as they moved the broadcasting to New York and the show’s setting to Harlem. Gosden and Correll played all the characters for a decade, before adding black performers Lillian Randolph and Ernestine Wade to portray the female roles. In the late 1930s, the fifteen-minute program broadcast five evenings per week, while no longer the smash hit that did so much to popularize serialized radio comedy, was still a very solid ratings getter, beloved of white audiences and some black listeners as well. Going into his 1937 radio audition, then, Eddie Anderson probably hardly even dared to hope that this single appearance on the Benny show would amount to much more than a few dollars in his pocket.

ANDERSON’S APPEARANCE ON THE BENNY

PROGRAM, MARCH 1937

Jack Benny’s radio program in the 1930s frequently contained minor roles that utilized ethnic characters with strong accents—Italians, Russians, Greeks, Scots, Irishmen, Germans, Schlepperman the urban Jewish trickster, Appalachian hillbillies, and tough gangsters. They were portrayed by voice specialist actors Benny Rubin, Patsy Flick, Sam Hearn, and occasionally writer Harry Conn. Conn had maintained that the surprise of an ethnic accent it was one of the surest ways to get a laugh from radio audiences. Nevertheless, among the dialect characters, the Benny show had utilized African American voices only infrequently, as waiters or bellhops at hotels—performing single lines that might have been covered by his ethnic comics. African American actor Clarence Muse had been hired twice in early 1936, to perform brief one-shot roles as a fellow jail inmate and a train porter. But nothing more came of that.42

Benny recalled in his autobiography that writers Bill Morrow and Ed Beloin, (who had been on the job one year) drafted an episode to be broadcast March 28, 1937, Easter Sunday, which involved the cast traveling to the West Coast on the Santa Fe Super Chief after the denouement of the Benny-Allen feud. The writers wanted to create a scene with Jack meeting someone on the train trip who, like so many waitresses and store clerks, would annoy him. Instead of the conductor or engineer or a passenger, they chose a Pullman porter who would impertinently frustrate him. Benny assumed they could utilize Benny Rubin for this small role, but Morrow pointed out that Rubin would look so incongruous to the studio audience at the live broadcast, a small white man playing a black character, that the audience would be too distracted to laugh in the correct places.43 Jack suggested Rubin could wear blackface, and the writers again objected that it would hurt the mood of the scene. Benny described the racial insensitivity that he, his writers, and most of white society held in the era that framed their notions about the character they sought to create: “He was a traditional Negro dialect stereotype. He had a molasses drawl and he ‘yassuh-bossed’ me all over the place. He was such a drawling, lazy, superstitious stereotype that even the original Uncle Tom would have despised him. However, in those days we were not aware of these racial aspects of comedy.”

With just a short time that week to get the part cast and episode rehearsed and broadcast, they auditioned five black actors. Eddie Anderson had not performed the most outstanding acting job of the group in reading the lines. Benny was nevertheless very attracted to the sound of Anderson’s voice, recalling that “he had a deep husky growl in his voice and his words came up through his larynx like there was a pile of gravel down there. . . . During the reading he modulated into a high pitched squeal that was marvelous. It sounded like ‘hee hee HEEEE.’”44 Anderson won the small part and earned $50 or $75 for his few minutes of work on-air:45

The scene—Jack and Mary are aboard the Super Chief

JACK: Gee, what a long trip.

MARY: Say Jack, look out the window . . . (giggles) They sure dress funny here in Hollywood.

JACK: Those are Indians . . . this is New Mexico.

MARY: Oh.

JACK: Hey porter, porter!

PORTER: Yessir?

JACK: What time do we get to Albuquerque?

PORTER: What?

JACK: Albuquerque!

PORTER: I don’t know, do we stop there?

JACK: Certainly we stop there!

JACK: Hmmm . . .

PORTER: I’d better go up and tell the Engineer about that.

JACK: Yeah. Yeah, do that!

PORTER: What’s the name of that town again?

JACK: Albuquerque.

PORTER: Hee, hee, hee! Albuquerque. What they gonna think up next?

JACK: Albuquerque is a town.

PORTER: You better check on that.

JACK: I know what I’m talking about. . . . Now how long do we stop there?

PORTER: How long to we stop WHERE?

JACK: In Albuquerque.

PORTER: Hee-hee! There you go again.

“I remember that first Sunday,” Eddie later recalled. “I wasn’t nervous—I had been a performer for years and if I ever had stage fright, it was so long ago I forgot it.”46 Eddie Anderson’s lively portrayal of the sassy porter who gave Benny a hard time by claiming to never have heard of Albuquerque made an impression on listeners and critics, as public reaction was apparently quite positive. Benny later recalled, “Eddie was a riot on that show and I was surprised nobody picked him up. We got so much mail, I decided to make him a regular, which I did after the summer. I made him my butler and chauffer on the show.”47 While Benny’s quote made Anderson’s incorporation into the show seem smooth and inevitable, in actuality, Benny and the writers did not have a solid idea for a permanent addition. They brought Anderson back on a second show on May 2 as an impertinent waiter (Pierre) in the “Buck Benny” skit, because they liked his voice.48

In a half a dozen other appearances on the Benny Jell-O Program that spring and the subsequent fall, Anderson played anonymous characters. Meanwhile, Anderson continued his day-labor in films and appearances at nightclubs, and also picked up several small one-time parts on other radio programs. Anderson was finally featured as a major continuing character on Benny’s December 26, 1937, episode. The episode revolved around a holiday party Jack was holding at his house, and the fact that he had hired a valet named Rochester Van Jones. The episodes contained some prominent lines for Anderson. Rochester’s wife (unheard) continuously called on the telephone, and Jack and Rochester took turns answering the calls (the wife very soon disappeared from the program’s narrative). Rochester sang a verse of a song, and Don Wilson involved him in doing the middle Jell-O commercial.

How the name “Rochester Van Jones” originated was a matter of debate. A 1939 Defender article claimed of the scriptwriters’ choice, “Rochester, they said, was phonetically perfect. Van has a tony touch and Jones is used as a sort of a great big let-down.” In a 1968 interview, Anderson maintained that it was Benny who thought up the name. “Jack modestly said that he can’t really remember, but the minute the name Rochester was mentioned, he knew it was the right one.49 In his autobiography, Benny noted, “Rochester was a good name for a butler because it does sound kind of English and it was incongruous for me to have an English butler. Also the word has a good hard texture. It’s a name you can bite in to. If I was mad at him, I could yell ‘RAH-chester.’ It was an ideal name when I lost my temper.”50

After Rochester’s introduction as a recurring character on the Benny radio program, Anderson appeared on about every third episode in early 1938. After the show writers made a few experimental attempts to include Rochester in the “work” of the radio program, appearing in the parody skits the radio cast undertook, the writers settled instead on a narrative frame in which Rochester was clearly Benny’s servant working at his home, not a cast member or employee of the radio station. As Benny explained Rochester’s role to a New York Times reporter, “Never is he supposed to be an actor or a part of the program. Always the audience thinks of him as my valet. That is why we never mention his name in the cast. The trick is to keep him in character.”51

The decision to keep Rochester’s realm of activity separate from the radio cast ended up expanding the situation comedy elements of the Benny program. The show’s writers worked to vary the program narrative, from episodes that completely followed the radio program production, to others that mixed in preparations before or after the show, to those that took place entirely away from the radio studio and had almost nothing to do with the show. To incorporate Rochester into the action, they began to experiment more often with comic scenes taking place between Jack and Rochester at home, or when Rochester phoned his employer at the studio, or when he drove Benny and the cast around town in the Maxwell. Rochester interacted only infrequently with other members of the cast, although as more shows included scenes at Benny’s home, Mary Livingstone frequently appeared and the two of them together would critique Jack’s vanities. When Jack found himself the owner of a pet polar bear, Carmichael (who had an appetite for gasmen), Rochester assumed another household duty in caring for him.

Because Rochester was separated in the show’s narrative from the others as valet and private person, not as a radio show performer, script dialogue referred much less often to Anderson’s other real life performances outside the world of the radio program than it did to the other cast members’ outside activities. While Phil Harris could brag about his band’s appearances at the Wilshire Bowl, and Kenny Baker could publicize his appearance in the film The Goldwyn Follies, Rochester did not get to talk about Eddie Anderson’s appearances at Los Angeles night clubs or the roles he played in films like You Can’t Take it With You, Jezebel, or Gone with the Wind. This has led some critics to argue that there was a persistent prejudicial downplaying of Anderson’s status on the show.52 The radio program’s dialogue sounded uneasy as characters begin to acknowledge Anderson’s skyrocketing celebrity as Rochester (especially when the radio-themed films were released).53 The show’s reticence to publicize Anderson’s doings also made Rochester the most fictional of the show’s self-reflexive characters who so thoroughly blended radio character and real-life identities.

On the flip side, Anderson soon found himself publically subsumed into Rochester’s identity, in both black and white popular culture. Everyone began calling Eddie “Rochester,” even his wife.54 As the radio scripts’ changing of Sadye Marks Benny’s name to “Mary” in indications of her lines meant that the actress had adopted her stage name in real life, it’s probable that people connected with the program were calling Anderson “Rochester,” as well, for the scripts list him as “Rochester” starting in October 1938. A July 1939 interview in the Defender claimed, “Anderson has become so accustomed to being called ‘Rochester’ that it is hard for him to remember his real name.”55

REACTIONS TO ANDERSON AND ROCHESTER IN THE

BLACK AND WHITE PRESS

Soon after his regular role began on the Jell-O Program, both white and black newspapers made especial efforts to inform radio listeners that Anderson was actually a black actor performing a black role.56 Given the paucity of African American participation in network radio programs, the black press had previously given little regular space to network program guides, oftentimes restricting their listings only to noteworthy appearances of black musicians and singers. In February 1938, the Atlanta Daily World and Chicago Defender began including the Jell-O Program in their radio guide—listed as “Rochester—NBC Red—Sunday 7 pm.”57 The California Eagle’s entertainment reporter in April 1938 acknowledged his readers’ reluctance to engage with radio when “good programs that give Negros more than two lines to say are few and far between.” He urged them now to turn on their receiving sets:

I immediately call your attention to Jack Benny’s Jell-O program, which for several years has been voted the most popular one of the air. The newest addition to Jack Benny’s cast is Eddie Anderson, a young Negro comic, whose excellent performance as Rochester, the butler, is bringing new and hearty laughs to the program every Sunday.58

The New York Amsterdam News interviewed Anderson in April, and reported that “He is treated equally well by all members of the cast, including Mary Livingstone, Phil Harris, Kenny Baker and Andy Devine, and is just as popular as any other individual on the program.” It claimed that Benny took a personal interest in him and treated him like a protégé. The article was accompanied by a photo of Jack Benny and Eddie Anderson posing in the studio with New Amsterdam News reporter Bill Chase. This was a coup for Chase, as few white entertainers were willing to be so photographed. The article also noted Anderson’s role in the recent film You Can’t Take It with You.59 Director Frank Capra was receiving kudos for supporting improved race relations, for the equality with which Anderson and Lillian Yarbro, who played servants, depicted as being treated. A 1939 Baltimore Afro-American brief profile when Eddie appeared in person at the Earle Theater was careful to portray him with dignity, mentioning that he had his own valet backstage: “That harsh, croaking voice which you hear when he plays Rochester is only a part of the act and is discarded for a pleasing, clear, deep voice when he is offstage. A reserved, ever smiling gentleman in reality, he never clowns or tries to display any of Rochester’s’ vocal mannerisms.”60 Optimists began to hope that Anderson, through these radio and film roles, was leading to a new era of more sympathetic depiction of blacks in contemporary American society, through comedy.61

Meanwhile the first article about Anderson in the New York Times painted a stereotype of a minstrel character: “Jack pushed me ahead and I sure does feel mighty thankful to him,” it claimed that Eddie said.62 Even the black press could occasionally depict Anderson in a similar manner. A syndicated article titled “Radio’s Famous Rochester” was published in the Pittsburgh Courier, the Atlanta Daily World, and the California Eagle in November 1938. It introduced Anderson as “The bewildering Rochester, who exasperates his boss with his laziness and larceny each Sunday night over the NBC-Red network.”63 It was rife with inaccuracies, and exaggerated Anderson’s previous connections to Benny, claiming that Benny saw Eddie in The Green Pastures and remembered to invite him to audition, supposedly when Benny was looking to cast a valet. It argued that Eddie paid hero-worshipping-levels of attention to Benny and imitated his cigar smoking at rehearsals.

THE SOUNDS OF RACE ON THE RADIO: MAKING

ROCHESTER VISIBLE

Michele Hilmes argues that U.S. network radio program creators were obsessed with delineating race on the radio. The ether and its performers were invisible, but inevitably, cultural construction of racial difference played out in this aural arena. Black characters (when they were included at all on the mainstream, white-dominated network programs) needed to be identified and labeled.64 To listeners today, the dismaying aspect of Rochester’s incorporation into the Jack Benny show narrative during his first years was the heavy load of what radio historian Michele Hilmes terms the “cultural incompetence” the character was made to carry, like the worst aspects of minstrel show characters.

Hilmes discusses the character failings demonstrated by Amos ’n’ Andy, which made them seem inferior to the presumed “superiority” of radio listeners. When like greenhorn immigrants they did not know how to function correctly in modern society, when they exposed how uneducated, or stupid, or naïve they were, when they were taken advantage of by the Kingfish or neighborhood sharpsters, when they got into trouble, they were labeled as losers. Radio listeners could assume these flaws were natural, even shared by other blacks, and could think Amos and Andy “deserved” their less-privileged status in life because of their “incompetence.” Hilmes argues that Gosden and Correll marked their characters as black through the narratives, dialogue, and performances. Amos and Andy lived in an all-black world, first on Chicago’s South Side and then in Harlem. They were naïve, foolish, and lazy, and constantly misunderstood or rejected the white-bourgeois rules of hard work and thrift needed to rise into middle-class society. They constantly mixed up and mangled words for humorous effect, although on the flip side, their neologisms and malapropisms were also wry, sharp, and often intellectually insightful.65 Part of the cultural “trouble” that Amos ’n’ Andy caused was that racist attributes were totally entwined with admirable aspects of the program. Gosden and Correll were superb writers and performers, with gifts for narrative, characterization, and comic timing. In the late 1940s, radio critic John Crosby would sincerely praise the show’s writing as the best on network radio.66 The show, by thoroughly mixing humorous, sympathetic characters with deplorable stereotypes, historian Melvin Ely has argued, could simultaneously appeal to both white racists and to blacks and whites sympathetic and supportive of the black community and race relations progress.67 Rochester’s character would face similar wrenching and contentious issues of character construction and audience reception.

During his first several years as a character on the Benny radio program, Rochester was saddled by the show’s writers with many racially stereotyped, minstrel show–like “cultural incompetence” cues: he was lazy; he stole watches, suits, and money from his employer. He was stupid and incompetent on the job (he burnt the clothes he was ironing, broke dishes, etc.). He had no control over his appetites over food and liquor, partying, brawling, and women; he was obsessed with pork chops, chicken, and watermelon. He shot craps and fought with razor blades. He lied, he bragged, he had a superstitious fear of ghosts. Over the months, nearly every widely held racist minstrel-show stereotype came out in the writers’ attempts to set Rochester out as “incompetent,” different, and inferior to the other cast members, who could be united in opposition, despite their own many idiosyncrasies and flaws, in their superiority and whiteness. These stereotyped differences helped justify why Rochester “deserved” to be ordered about and yelled at, and paid so little by his employer. Here are a few examples:

May 29, 1938, in a parody of “Tom Sawyer,” Jack plays the school teacher conducting a recitation:

JACK: Now, Rochester.

ROCHESTER: Yes, boss.

JACK: Can you name the Seven Wonders of the World?

ROCHESTER: Yes sir!

JACK: What are they?

ROCHESTER: The Sphinx, the Pyramids, the Hanging Gardens, and four pork chops!

JACK: Now Rochester, pork chops are not included in the Seven Wonders of the World.

ROCHESTER: I guess you’ve never been in Harlem Geography.

October 2, 1938, Jack is at home, getting dressed to go to the studio for the season’s first radio broadcast:

JACK: You know, it’s a funny thing, but every time you press my pants, you burn a hole in them.

ROCHESTER: Yeah, that is funny.

JACK: Well, don’t laugh. Oh well, I’ll put on an old pair so I won’t be late for breakfast. You know Rochester, sometimes I don’t know why I pay you.

ROCHESTER: I don’t even know WHEN!

JACK: I told you I’d pay you as soon as I went back to work. Right now I’m short of cash.

ROCHESTER: What’s that green stuff in your mattress? Grass?

JACK: Yes, it’s grass!

ROCHESTER: Well, I mowed some of it last night.

A further aspect of Rochester’s early depiction, which was tied to the idea of keeping him separate and distinct from the radio cast members, was the writers’ dogged determination to delineate Rochester’s physical and visual racial difference. They did this by repeatedly describing his blackness. In an invisible medium where everything was colored (pun intended) by the listeners’ imaginations, the show’s writers tried to milk humor, and reinforce awareness of racial difference, by regularly having Jack note the blackness of Rochester’s body:

November 13, 1938, Jack, Mary, and Rochester have gone to visit a fortune teller’s home, and its dark and creepy inside:

ROCHESTER: This place is darker than a telephone booth in Harlem.

JACK: Well, where are you?

JACK: Open your eyes so I can see you.

November 5, 1939, the cast is getting ready to perform a radio skit parodying the current MGM film The Women, and Jack insists that all the men on the show have to take female roles (Jack himself is taking Norma Shearer’s part); Jack calls Rochester in (as they are short of performers) to take a role as his maid:

ROCHESTER: Your maid? Why can’t I be your valet?

JACK: Because I don’t want a man in my room when I’m dressing. You’re going to be my maid.

ROCHESTER: I ain’t gonna wear no dress.

JACK: You are, too. . . . Now, fellas . . .

ROCHESTER: I ain’t gonna wear no mascara.

JACK: You are, too! . . . Now, fellas . . .

ROCHESTER: It ain’t gonna show!

Yet these denigrating and derogatory characteristics of Rochester were always counterbalanced by the Rochester character’s quick wit, and his irreverence for Benny’s authority, accentuated by his inimitable voice and the wonderful timing of his pert retorts and disgruntled, disbelieving “Uh huh” and “Come now!”

ROCHESTER: “When we start on our vacation, does that mean I’m off salary for 14 weeks?

JACK: It certainly does. You’re just like me, Rochester. When I don’t get it, you don’t get it.

ROCHESTER: When you GET it, I don’t get it!68

Rochester annoyed Jack, but also critiqued every order and action. With an air of informality, Rochester usually called him “Boss” and not “Mr. Benny.” He also had a far more sophisticated vocabulary than Phil Harris or Jack. The Benny show writers gave Rochester all the punchlines in his interactions with Jack; he had the ability to ridicule and criticize his employer, not having to keep his thoughts silent and to himself. This lively bumptiousness raised his character above the much more stereotypical black characters then current in American radio and film. He always remained a loyal servant and had to follow Jack’s orders, so he was palatable to those racists most resistant to social change, and yet, in a small way, Rochester spoke truth to power, and he was portrayed by an actual African American actor, so he gained sympathy and affection among black listeners, too.

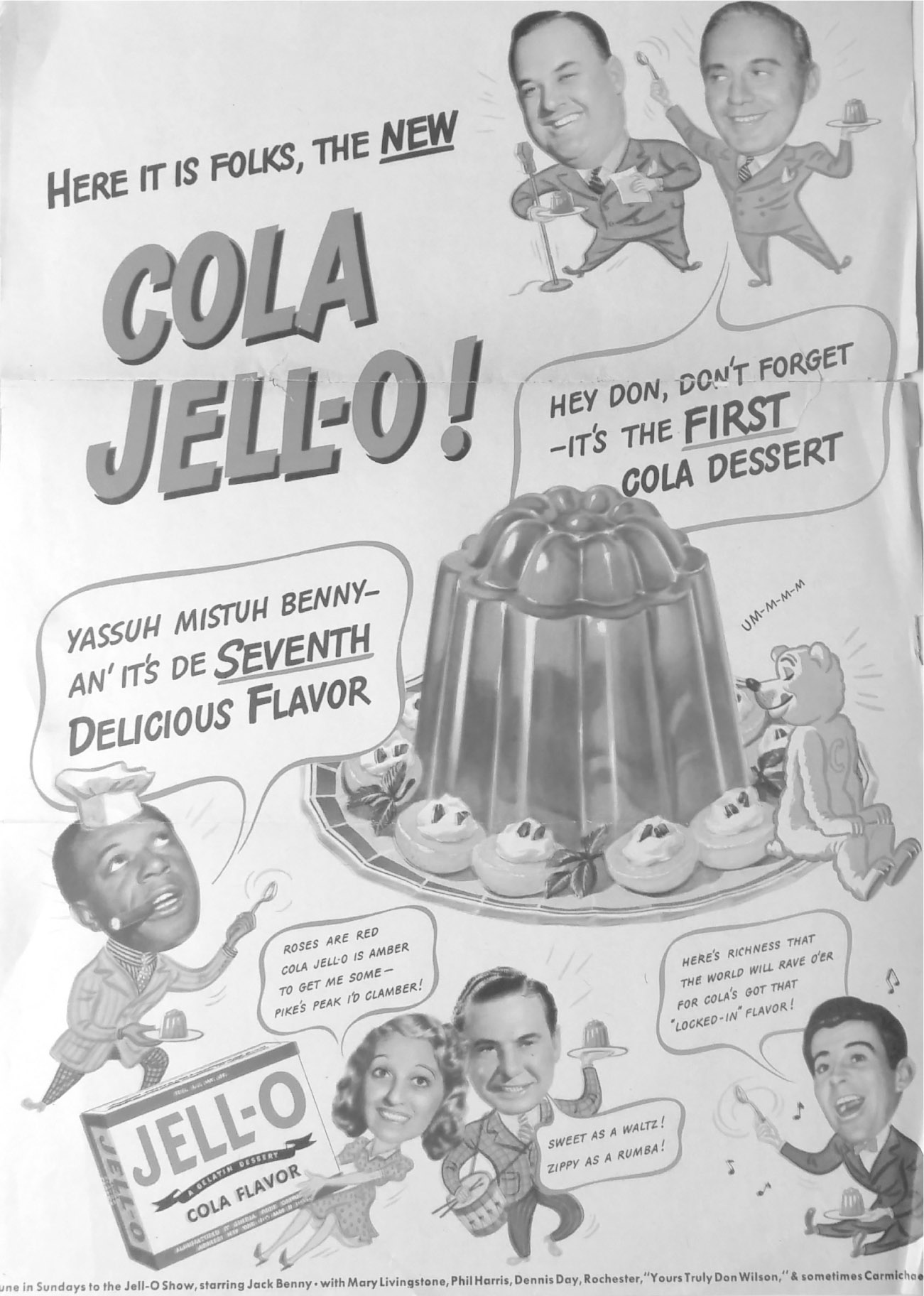

FIGURE 12. A rare appearance of Eddie Anderson as Rochester in a print advertisement for Jack Benny’s radio sponsor’s product, Jell-O. The Rochester character here is shown voicing more stereotypical-type language than writers were putting into his radio and film dialogue. Advertisement for Cola Jell-O, Life, circa Winter 1942, unknown date. Author’s collection.

The racial tensions inherent in Jack’s relationship with Rochester (employer/employee, superior/inferior, master/slave, and yet informally joking colleagues interacting with some sense of equality) literally collided in the February 5, 1939, Jell-O Program episode. The feud between Fred Allen and Jack Benny had reheated. Jack ordered Rochester to drive him and Mary out to Andy Devine’s farm in the San Fernando Valley in order to cheer Jack on as he trained for a possible boxing match against his rival. In need of a sparring partner, Jack conscripts a reluctant Rochester. Jack and Rochester start sparring, and we hear sound effects of boxing gloves making contact. Andy says, “Hey Jack, with you and Rochester sparring around, it looks like you are shadow-boxing.” Jack then pulls a dirty trick. He calls out to Rochester to look behind him, and when Rochester is distracted, smacks him hard in the face. Jack crows, “Bet I gave you a black eye!” Rochester retorts, “You’ll have to peel me to find out!” They spar a little more. Then Rochester calls out to Jack, “Look down at your shoe laces!” and punches Jack in the face in retribution for the sucker punch. Jack collapses on the ground, and shouts in a garbled manner—he’s lost his bridgework. While Mary and Andy scramble to search for his missing false teeth, Jack yells that Rochester is fired, while Rochester hides up in the rafters of the barn. As Benny recalled the episode in his autobiography,

There was the sound of an arm swishing through the air. The crack of a gloved fist meeting a glass jaw. The thunk of a body fitting the floor. “Boss, boss,” Rochester cried, “git up, git up!” I rose. So did the South. Thousands of indignant persons below the Mason-Dixon Line wrote in to complain that permitting my Afro-American butler to punch me in the face was an attack on the white race and the dignity of the South. Until [the I Can’t Stand Jack Benny contest] . . . this incident brought the heaviest mail we ever received on the program. You’ve got to realize that most of my life I’ve been a political innocent. It never occurred to me there was anything offensive in this humorous little episode. I was amazed at this revelation of people’s strong feelings on the subject of race. To me, I was just doing a comedy show.69

Benny’s radio show never again ventured into even hints of physical altercations between Jack and Rochester.

Given that the Jack Benny radio show was airing in 1930s, with the Civil War just seventy years past and race relations in America at a nadir of widespread prejudice and Jim Crow laws, and given how sharply Jack ordered a willing Rochester around, demanding so much for so little in return, some critics have likened theirs to a “master and slave” relationship. Theirs was joined by other uneasy, unequal relationships on the program, from Jack’s imperious treatment of his show cast, the Sportsmen, and the band musicians, or Jack’s terror of his own bosses (sponsors and network radio executives, film directors, and producers) who treated him as dismissively as well. Dennis Day’s overbearing mother Lucretia barked out commands for her timid son to obey, and both Dennis’s and Mary’s mothers batted their lazy, weak husbands around.

The relationship that Jack and Rochester played with was rooted in ancient stock characterizations and comedy plots, found in Greek comedy, Italian commedia dell’arte’s Harlequin and Pantalone, French farces, and Shakespearean comedies to Mark Twain satires, drawing room comedy, and vaudeville and silent film’s slapstick zaniness. European and American literary and theatrical history has been filled with stories involving trickster slaves, witty servants, and grumpy old, demanding masters. Whether they are deviously helping young lovers unite in spite of parental opposition, tweaking the old master’s vanity, or being sly jesters telling the truth to old men, sly servants overrode their subservient positions in every possible way, while just trying to get enough food (and/or love) to survive another day in a harsh world.

In the decades that the Benny program aired, many listeners would have been familiar with another famous model of a sagacious valet/butler much smarter than his employer—Jeeves and Bertie Wooster. British novelist P. G. Wodehouse created Jeeves in 1915 as a “Gentleman’s personal gentleman” serving wealthy, stupid, and foppish young British aristocrat Bertie Wooster, in a series of eleven novels and thirty-five short stories that stretched from 1919 to 1974. Jeeves was incredibly smart and well read, wryly humorous and totally in control of “Master” Bertie’s life. Jeeves’s brilliant plans managed to extract Bertie from whatever sticky social situation in which he ineptly and regularly immersed himself. Jeeves could solve any problem. Attempts were made to translate the stories to film in the mid-1930s with Arthur Treacher playing Jeeves, but they weren’t half as inspired as what Benny and Anderson were creating.

Nevertheless, the American cultural context of the relationship of Jack and Rochester, created within the historical legacy of slavery, widespread prejudice, poor race relations, and huge racial divides, made it very possible for radio listeners to understand Jack and Rochester’s relationship as plantation based, with Rochester’s acceptance of his meager lot taken as the way African Americans “should” acquiesce to white authority, accepting never being anything more than servants, loyally caring far more about the welfare of employers’ families than their own. It would comfort conservative whites who might see the relationship through the prism of the appropriateness of Jack ordering Rochester around and the servant having to do the master’s bidding under pain of punishment. But for black listeners, the fact that Rochester acquiesced to Jack’s demands, that he didn’t quit because of lack of wages or poor treatment or for a better opportunity, led some other listeners to categorize Rochester as a stereotypical Uncle Tom, comfortable in his subservient role, no matter how oppressed he might be.

Why didn’t Rochester just quit? What kept him tied to Jack, and accepting of the endless indignities of his servant role? The radio show’s narrative always struggled with explanations. Rochester would say he could not leave because he loved his boss so much. On the other hand, when Jack grumbled about Rochester’s thieving and cast members would ask why Jack didn’t fire him, Jack would reply with an excuse like “I can’t. He’s got some letters I wrote to Garbo, and he won’t give ’em back!”70 To newspaper reporters, Benny explained that Jack’s relationship with Rochester as based on affection: “He knows I like him, and no matter what he says or does he knows I won’t fire him.”71 Their relationship seemed like a family obligation, a strong bond of love and obedience and desire for approval that seems more like parent and child, or husband and wife. A paid employee should not have to owe such patient allegiance to an employer that treats him so badly. Writers who defended the Jack and Rochester relationship talked about Rochester having a deep-down love and affection for Jack, a determination to put up with the guff and do his duty. On the other hand, liberal critics began to chastise Anderson for acquiescing to the role. The Defender would try to head off criticism with denials in 1939: “No Uncle Tom is this man ‘Rochester.’ He makes it clear that he is valet deluxe to comedian Jack Benny and polar bear Carmichael only on the radio and in the movies. Outside of work, he is plain Eddie Anderson.”72

ROLES IN BENNY’S PARAMOUNT FILMS MAKE ANDERSON

AN INTERMEDIA STAR

In late 1938, the Paramount film studio hired RKO director Mark Sandrich to resuscitate Jack Benny’s movie stardom after a string of lackluster musical variety films. As I recount in the Intermedia stardom chapter, Sandrich developed the idea of incorporating Benny’s radio identity and the sound, pacing, and energy of the top-rated Jell-O Program into the movie Man About Town.

After putting Phil Harris into a role, Sandrich decided to incorporate Eddie Anderson into the film, too, playing a valet named Rochester who worked for theatrical producer Bob Templeton (Jack). Anderson had been a regular cast member of the Benny radio show for about a year, and Rochester’s popularity had been growing rapidly. During the weeks of film production, however, on the radio show, while Jack and Phil joked about happenings on the Paramount sets, no mention was made of Anderson’s involvement in the filming; the narrative was intent on keeping Rochester contained as Jack’s private employee. Meanwhile, Sandrich kept expanding Anderson’s role as the film was in production, adding to Anderson’s comic repartee with Benny and involving him in several musical numbers.

Even the best-intentioned efforts, then as now, in exploring humor that is connected to race can go awry, because no matter what intent a joke maker puts into a jest, it is always open to a variety of interpretations by different audiences. Sandrich saw something he thought was amusing while Anderson was performing a solo dance number in a large courtyard set that was surrounded, for some obscure reason, by a collection of live zoo animals in cages. The Los Angeles Times reported the incident as “Dance-Minded Chimp Will Appear in Film”:

Some of the most unusual scenes in motion pictures happen by accident. Scene: the country estate set of an English gentleman, which boasts a private zoo and aviary. Eddie Anderson, erstwhile Rochester and valet to Jack Benny in “Man About Town” at the Paramount studio, is performing a comedy dance routine. Mark Sandrich, director, is suddenly attracted to an offstage scene which is going on while the cameras are recording the dance. A big chimpanzee in a cage is not only jumping up and down, but he is keeping time to the rhythm of the swing band which is playing, in a dance of his own. The director ordered another take and the simian did it again. Yesterday Sandrich shot a scene of the dance-minded chimpanzee doing his stuff. And it should be one of the best laugh scenes in Man About Town.73

It is difficult to watch this movie scene today and not think that Anderson and the animal are being paired, and that it seems denigrating. Perhaps the scene was understood by others at the time differently—some spectators might have been so enthralled with Anderson’s dancing that they hardly noticed the background commotion, and others, whose prejudiced sensibilities might have been rankled by the visible equality of Benny and Anderson in their co-starring scenes together, might have been mollified to see Anderson’s stardom undercut by a chimp imitating him.

Man About Town, a lightweight film, was far funnier and fresher than anyone had anticipated. Benny and Anderson had more screen time together than any nearly any other black and white actors had performed in Hollywood film. Their radio relationship seemed even closer when vividly portrayed on the screen with an easy informality. Anderson got a chance to shine, throughout the film, with excellent timing in his comic banter, and a lively, engaging performance as actor, dancer, and singer. The film’s press book touted a new star, as if Anderson had never appeared in movies before:

It has Rochester—who must be given special mention because it the screen debut of Benny’s famed radio stooge—and what a debut! Rochester (Eddie Anderson) has delighted millions on the air—and he’ll have your patrons flat on their backs in the aisle, both with his straight comedy role and with his hysterically comic dance routines.74

Man About Town received an extraordinary level of intermedia promotion at its June 1939 premiere. Paramount Studios, radio sponsor Jell-O, Young & Rubicam, and the NBC network all contributed to a massive premiere and celebration held in Jack Benny’s hometown of Waukegan. While the elaborate festivities were all supposed to honor Jack Benny the film and radio star, Eddie Anderson and the Rochester character were celebrated as co-stars. Anderson was given nearly as many special awards, keys to the city, and fireman and policeman’s badges as hometown hero Jack Benny. No other African American media star had received a reception like this outside of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson’s fetes in Harlem. The promotional week in Waukegan involved parades, speeches, and special awards dinners. Over 100,000 people flooded the streets of the gritty northern Illinois town and a thousand policemen were required to keep order.

Reviews of Man About Town in the trade press and newspapers across the country reacted with surprise to the humor and sprightliness of the film, and to the raucous reception it received from audiences. Moviegoers were delighted with Anderson’s performance, white and black, Northern and Southern. New York’s Cue magazine was taken aback:

Brightest star in the picture is, oddly enough, not Benny but the ebony-hued, sand-paper voiced, irrepressibly funny man-stooge, Eddie Anderson. Eddie is the handy man-valet known on the Benny radio program as Rochester. In Man About Town, Benny has generously afforded Rochester plenty of footage, lines, dances, songs, close-ups and pricelessly funny gags, giving him the cinematic opportunity of his life—and Rochester responds nobly.75

Even one of the deans of the New York film reviewing community, Howard Barnes of the New York Herald Tribune, found something nearly utopian in the possibilities for representation of black people, after seeing Man About Town.76 He excoriated Hollywood for “foolishly ignor[ing]” talented black dramatic performers in the past, and saw a glimpse of something new in this film: “Anderson’s Rochester was obviously designed as nothing more than a foil for his [Benny’s] wise cracks and antics. And yet you are likely to come away from the picture remembering the colored player’s laugh-provoking and versatile performance as vividly or more vividly than the star’s.”

After his prominent role in Man About Town, the African American press detailed Anderson’s burgeoning fame in mainstream white popular culture. The Defender, California Eagle, New Amsterdam News, Atlanta Daily World, Baltimore Afro-American, and others published large spreads of photographs, interviews with Anderson, biographical sketches, and praise for the film.77 Black movie theaters both across the segregated South and in the North advertised the film featuring Rochester’s name as starring over Benny’s, and many white theaters listed Benny and Rochester on their marquees as co-stars. Anderson spent the summer of 1939 on a triumphant tour of leading black entertainment venues in Chicago and New York and a lucrative series of headlined engagements at major theaters across the nation before the fall radio season began.

When the Jell-O radio show resumed broadcasting in October 1939, the program’s narrative struggled to deal with Rochester’s on-air, on-screen, and public fame, given that his radio character was supposed to be a private servant.78 Paramount meanwhile rushed Benny and the radio cast into a new film to capitalize on their success, titled Buck Benny Rides Again, (BBRA) with Mark Sandrich again directing. Anderson, Don Wilson, Phil Harris, Dennis Day, Mary Livingstone, and Fred Allen would all contribute this time. Dialogue on the radio show revolved for weeks around the new film’s production. In a December 1939 episode, Jack and Mary discussed the filming going on at Paramount, and Jack mentioned that Phil and Andy Devine would be appearing in the picture. “Did you leave anyone out?” Mary asked, in an opportunity to heckle him:

JACK: “Oh yeah . . . Rochester is in the film, I forgot.”

MARY: “You’ll remember when it comes out.”

Paramount mounted an elaborate promotional campaign for BBRA in April 1940, focusing nearly equally on Anderson and Benny. Paramount’s press book for BBRA was awash in photos of Anderson (whom it identified only as Rochester), dancing, singing, wrangling Carmichael the polar bear, and interacting with Benny. The press book offered local theater managers a quarter-page newspaper photo spread of Rochester and Theresa Harris dancing, titled “Doing the Rochester Shuffle-Off.” The Paramount publicity department declared, “This strip sequence of Eddie Rochester Anderson doing the ‘Rochester Shuffle’ should appeal equally to jitterbugs and followers of Fred Astaire. Rochester’s’ a natural space-stealer as well as a picture stealer. Plant this strip now!”79

Newspaper advertisements provided for the film prominently featured illustrations of Anderson along with Benny. In small ads, Rochester’s face was paired with Carmichael the bear. The larger ads and theater posters linked Rochester to both Benny and to Fred Allen. Rochester was depicted, cigar dangling from his mouth, clinging to the top of a large cactus, holding a portable radio by its handle. Fred Allen’s voice emerged in a text balloon from the radio, quipping, “Imagine that tenderfoot on a horse! If Benny ever gets on a jackass, you won’t know who’s riding who!” In a dialogue balloon, Rochester said “Mr. Allen sho’ do say funny things.” Benny, riding in the Maxwell, retorted, “Oh shut up, Rochester.”

While this huge publicity buildup of Eddie Anderson was occurring, Hattie McDaniel had a much more contested reception surrounding the December 1939 premiere of Gone with the Wind. Jill Watts and Matthew Bernstein have documented the refusal of white Atlanta municipal authorities to allow McDaniel to publically participate in the world premiere of producer David O. Selznick’s film in that deeply segregated Southern city.80 Even though McDaniel was nominated for and won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role, Southern whites did not want to celebrate her performance. Southern blacks rejected the film entirely for its depictions of racial attitudes, slavery, and the Confederacy. Even though Anderson and McDaniel both portrayed servants in these films, popular understanding of their performances (and public reaction to their stardom) was impacted by a myriad of factors, highlighting the differences between historical melodrama and contemporary musical comedy, and the relationships of Jack and Rochester versus those of Mammy and Scarlett. While it is fascinating that Anderson could gain so much more public appreciation of his star performance, his success came at the price of seeming to be submerged in the role of what both racist whites and the black intelligentsia would label as “public clown.”

So differently than what MGM had done in Atlanta, in April 1940 Paramount’s publicity department mounted twin premieres of Buck Benny Rides Again, one at the flagship Paramount Theater in Manhattan (which broke all box office records for the first day’s shows), and the night before, a huge celebration at the Loew’s Victoria Theater in Harlem, a 2,400-seat picture palace located on 125th Street, adjacent to the Apollo Theater. The Harlem events received live radio coverage and extensive stories in the black and white press. “‘Hollywood Goes to Harlem!’ is the slogan adopted by Paramount for the first world premiere of a motion picture ever held in Harlem,”81 the black press gleefully reported.

The BBRA premiere week in New York City was the highest point of Eddie Anderson’s star career. It started with a ceremonial parade held in Harlem the Thursday before, when Anderson alighted at the 125th Street station to be greeted by area African American dignitaries. More than 3,000 people jammed the sidewalks to see the group parade up several blocks to the famous Theresa Hotel, with Anderson riding a large black stallion.82 On Sunday evening, the Benny cast performed their radio show from the stage of the Ritz Theater. On Tuesday night, a huge parade brought Anderson, Benny, Sandrich, Benny cast members, Fred Allen, and New York entertainment celebrities to the Loew’s Victoria Theater. Coverage was broadcast on radio station WHN. Crowds estimated at 150,000 filled the streets, 20,000 people gathering outside the Loew’s Victoria to see the celebrities arrive. Three hundred city police on horseback kept pushing into the crowds, aggressively maintaining order.83 A New Amsterdam News reporter maintained it was a bigger public event than Marcus Garvey’s parades or even the welcome home reception for Jesse Owens returning triumphantly from the Olympics in Berlin.84

Inside the theater, with the local broadcast continuing, Willie Bryant acted as master of ceremonies on stage, Bill Robinson introduced dignitaries in the audience, Jack Benny and Rochester performed a skit on stage, and then Fred Allen spoke. The principals stayed to open the second screening, then everyone repaired to the Savoy Ballroom, where a huge testimonial reception was held to honor Anderson.85 Everyone in Harlem society was there—including Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Bill Robinson, Ethel Waters, Jules Bledsoe, city dignitaries, and prominent African Americans in city and state government, the police and fire services, and the military.

Reviews of Anderson’s performance in BBRA were uniformly laudatory, although some articles in the mainstream white press twisted things around to give most of the credit for Rochester’s role to Benny, and a few betrayed deeply held racial attitudes. The New York Showman’s Trade Review reported that Rochester

smashes through to the spotlight on several counts. For one, he sings “My My” especially written for him, in a voice as charming and soothing as a cement mixer. He displays an amazingly delicate talent as a dancer and he tops the Benny gags with something funnier at every shot made by the master. It is with a spirit of bland generosity that Benny steps back and lets Rochester have the spot, for while he sacrifices himself as an actor, he proves himself tops as a showman.86

The New York Herald Tribune’s critic Howard Barnes, who had waxed eloquently about Anderson in Man About Town, joined the chorus of appalled serious film critics who excoriated this film for being so radio-focused and uncinematic. On the other hand, he was delighted at the opportunity that black performers had been given: “Once more he [Anderson] and Miss Harris demonstrate that the photoplay is a natural medium for Negro performers and that they should have a bigger hand in its exploits.”87

The impact of Anderson’s and Benny’s unusual position as interracial co-stars in a Hollywood film contributed to fascinating little moments of possibility in the black community’s popular imagination. In fall 1939, Dr. Benjamin Mays assumed the presidency of Morehouse College, the prestigious all-male undergraduate component of Atlanta University. The college faced dire financial challenges, which Mays addressed by careful fiscal budgeting and much more strictly enforcing payment of tuition bills by the students. By spring of that school year, just as BBRA was playing in both Atlanta’s segregated black and white movie theaters, Morehouse students started to kiddingly call Dr. Mays “Buck Benny,” to honor his frugality. The nickname stuck. For the rest of his career, students, faculty, staff, and alumni affectionately used it. Yet as the years rolled on, this utopian interracial moment faded, and everyone forgot about the movie. Students still called Dr. Mays “Buck Benny,” but no one could remember where it came from.

Other African Americans optimistically appreciated what this film and the hoopla surrounding it could possibly mean for a movement toward loosening of racial boundaries and amelioration of inequalities in the entertainment world. A letter to the editor of the Chicago Defender noted:

Dear Editor: I take this means of congratulating Eddie “Rochester” Anderson for his splendid work in Buck Benny Rides Again. There has been much favorable comment from the white people of this town. They say it was really Rochester’s picture and they seem to have enjoyed it much more than some other pictures. I know it was much better than some I have seen similar to this one. Two of the pictures I may name were Imitation of Life and Gone with the Wind. Both of these were outstanding pictures, but somehow Buck Benny Rides Again seems to bring about the good will between the white and colored races which has been and is being fought for so vigorously by a people who are approaching the shouldering of arms for a flag and country they have not the privilege of serving sincerely. I feel we should not overlook any opportunity to encourage our people. I sincerely hope all colored people who have not seen this picture will do so at their first opportunity.

S. Springfield 503 Fifth Street, Coffeyville, Kansas88

During the week after the big celebrations in New York, Anderson flew up to Boston. He’d been invited to be guest of honor and entertainer at a Harvard Freshman “smoker,” a big stage show that was also to feature Cab Calloway’s band. En route to Boston by airplane, he was intercepted at a layover in Providence by a group of MIT students masquerading as his Harvard hosts. They “kidnapped” Anderson, drove him to Cambridge, and kept him sequestered in their fraternity house for several hours, before finally taking him to his scheduled performance (in a motorcade of twenty-five cars) over at Harvard. After the show, in the early hours of the morning, a full-fledged riot ensued between the rival university students, complete with sixty policemen called in, punches thrown at students, water balloons tossed at the cops, false fire alarms set off, traffic snarled in Harvard Square, and eight Harvard students arrested.89 Entertainment industry people shook their heads in wonder, marveling that no producer could buy such great publicity that Paramount had just gotten for free. The next evening, Anderson, in connection with the opening of BBRA at the Metropolitan Theater, was greeted by a crowd of 10,000 (Boston’s black population predominating) who lined a torch-lit parade through the South End to a special reception at a restaurant on Tremont Street, where Anderson was made an honorary member of the fire department and was feted by the leaders of Boston’s black community.90

UTOPIAN RACIAL HOPES, AND ANDERSON’S

CAREER IN HIGH GEAR

In 1940 and 1941, Eddie Anderson found prominence everywhere at the national level—in radio, film, and stage appearances, and in the press. He garnered film awards from the black community. The Sepia Theatrical Writers Guild, a West Coast newspaper writers group, named him comic male star of the year for Man About Town.91 The NAACP’s California branch honored Anderson and Theresa Harris for their work in BBRA.92 In Los Angeles, Anderson won the honorary title of “Mayor of Central Avenue.” The role was not merely ceremonial: the “mayor” acted as a private intermediary with the Los Angeles mayor and police departments, trying to stem the brutal treatment that black Angelenos received at the hands of the city’s cops.

The success of Eddie Anderson’s co-starred films with Jack Benny fueled optimistic hopes in the black press that prejudiced racial attitudes could be softening in the white South. Rochester was hopefully opening a wedge to destroy the old myths that racist Southern whites refused to watch or listen to black performers, the myths to which film and radio producers so stubbornly clung. Pittsburgh Courier film editor Earl J. Morris lauded Anderson as a “goodwill ambassador” bringing a message of respectability and equality to whites in Hollywood and across the nation.93 On screen he was not an “insolent, ignorant Negro . . . his lines contain witty wisdom” and he was “sagacious”:

Eddie “Rochester” Anderson is Public Valet No.1. He is the patron to the colored domestic workers throughout these United States. “Rochester,” diminutive prince of pantomime and comedy king, is the “Little Napoleon” of the vast empire of colored domestic servants. “Rochester” and Jack Benny have improved the lot of maids, cooks, butlers, valets and what have you. They show their appreciation to this stellar comedy team in every way that they can. About three million maids, cooks, butlers, et cetera, serve as many families “the delicious flavors” and make them like it. And the Negro motion picture audience turns out en masse to see the comic antics of this pair on the screen.

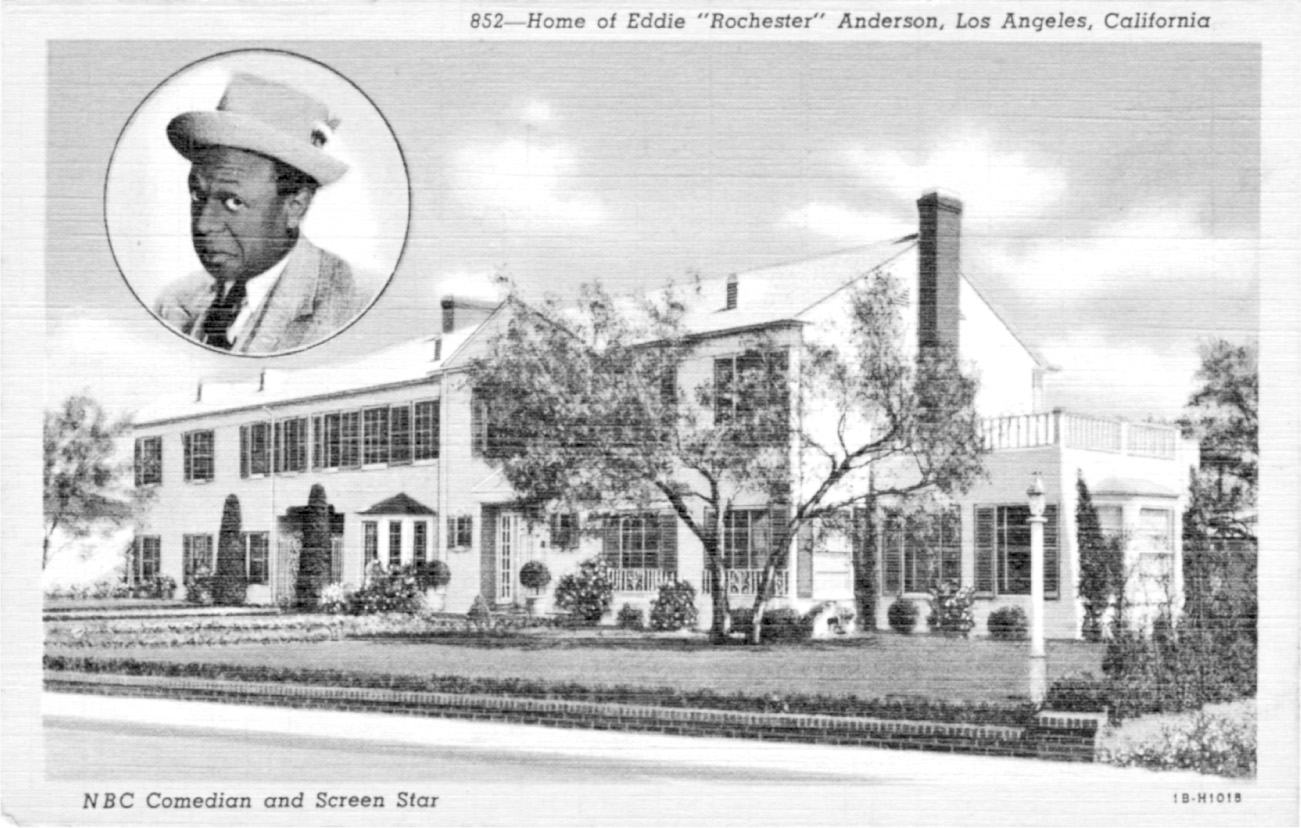

FIGURE 13. By the 1940s, Eddie Anderson had become the most prominent African American star in Hollywood, and tourists sent home postcards of his elegant home. Circa 1942. Author’s collection.

Anderson and Benny both received nationwide press coverage in spring 1941 for being chosen among a dozen recipients of citations from the New York City–based Schomburg Center for its Honor Roll in Race Relations for 1940. The Schomburg’s director, Dr. Lawrence Reddick, saluted a dozen African Americans and six whites “who had done the most for the improvement of race relations ‘in terms of a real democracy.’” The center honored “Eddie Anderson, better known as Rochester, for his Harlem premiere of Buck Benny Rides Again and for his Sunday evening performances with his fellow-comedian Jack Benny” and “Jack Benny, for recognizing dramatic talent irrespective of color. His fellow comedian Rochester is cast in roles that are neither personally humiliating nor indirectly derogatory to the Negro people.”94

With war looming closer, and the importance of black workers to the U.S. war effort becoming more widely recognized, a better share of equality for African Americans became a prominent topic in the black community, and also among leaders in Washington. Within the continuing climate of tendentious race relations, some members of the African American community were gaining hope. There was potential for black workers to get better jobs, and anticipation that black performers in film and radio could get more prominent and respectable roles.

Eddie Anderson’s stardom positioned him to represent the optimistic hope that perhaps race relations and opportunities for blacks were improving. The terrible and hurtful representations of blacks in the mass media of the past could finally be put aside. The California Eagle voiced these hopes in an editorial titled “Rochester, The New Day.”95 It claimed that after twenty-five years of dreadful representation in American mass media,

two years ago America became conscious of a new thought in Negro comedy. It was really a revolution, for Jack Benny’s impudent butler-valet-chauffer, “Rochester Van Jones” said all the things which a fifty year tradition of the stage proclaimed that American audiences will not accept from a black man. Time and again, “Rochester” outwitted his employer, and the nation’s radio audiences rocked with mirth. Finally, “Rochester’ appeared with “Mistah Benny” in a motion picture—a picture in which he consumed just as much footage as the star. The nation’s movie audiences rocked with mirth. So, it may well be that “Rochester” has given colored entertainers a new day and a new dignity on screen and radio.

• • •