Rochester and the Revenge of Uncle

Tom in the 1940s and 1950s

By 1941, after four years on the radio with Jack Benny, playing the sly comic servant Rochester, and three films at Paramount in which he and Benny practically co-starred, Eddie Anderson had achieved unprecedented levels of popularity in mainstream American media and broken new ground for interracial acceptance. Hopes in the African American community were high that Anderson’s success was the harbinger of a new era of increased opportunities and recognition for black performers. Despite the occasional lapses into stereotypical minstrel show–type behavior with which Benny’s radio writers still saddled Rochester, Anderson used his unique voice, wit, intelligence, and great sense of comic timing to transform the role of valet, butler, housekeeper, and chauffeur into a complex, very human character. With the start of World War II and the government’s efforts to promote racial tolerance and greater inclusion of African Americans in the labor force and military, Anderson’s professional prospects expanded further, as he served as a useful spokesman for those ideals. He was now a big star, with a multifaceted career that spanned movies, radio, musical shows that toured the country, and recordings of novelty songs, with every indication that it would only continue to grow. Anderson was offered a major role in an all-black-cast film at MGM, and minor but prominent roles in other Hollywood films.

Massive cross-over success almost coalesced for Anderson. But then, unanticipated events and complex cultural change conspired to heap as much criticism as praise upon his head. Accusations that Rochester was an “Uncle Tom” rose from black critics on the one hand, and objections to his egalitarian relationships with whites erupted from white racists on the other.1 To be acceptable to whites, Anderson, like other veteran black performers who tried so hard to carve out careers in movies and radio—such as Hattie McDaniel, Ethel Waters, Louise Beavers, and Clarence Muse—had to make many compromises with which liberal critics were increasingly dissatisfied. Benny and his writers further moderated Rochester’s disreputable habits during the war years, but unfortunately, again and again, the limitations of their ability to permanently change their own racial attitudes when writing scripts set off uproars within the black community.

In his history of African American culture in Los Angeles in the 1940s, R. J. Smith describes the ambivalence that black listeners experienced when they heard Rochester on the radio—“every appearance on the Benny show was likely to simultaneously further and undermine stereotypes.”2 Much of the racialized humor on the program was old and stereotypical, black audiences judged, but there was nevertheless something new in Rochester’s relationship with Jack. Rochester called his employer the more informal “Boss” rather than “Sir.” Jack was far more often the butt of the jokes than Rochester. Rochester could give voice to criticisms of Jack, mock him, and make numerous complaints about his never-ending duties and lack of pay, yet he was never punished. Rochester, more than the other servant characters in broadcasting and film, was authentically black. Even if this only meant carousing through Los Angeles’s Central Avenue and Harlem, Rochester had a life outside of working for “the Boss.” “It was this license to speak openly that made Rochester a hero on Central Avenue, ” Smith concludes.3

This chapter chronicles the difficulties Anderson faced in the 1940s, when often-simultaneous eruptions of white racism on the one hand, and black criticism on the other made his career more challenging than ever to negotiate. Even while Anderson prospered in the Rochester role and created superb comic repartee with Benny, cracks in the utopian vision of interracial stardom appeared, and compromises on all sides came hand in hand with success. Anderson was the most prominent and highest paid black performer on primetime network radio, but too often he still had to make jokes about craps shooting, and enact minstrel show behaviors. He landed a role in a prestigious film, 20th Century Fox’s Tales of Manhattan, but then faced backlash from a new generation of black critics who disdainfully charged him with being an Uncle Tom. Anderson’s leading part in the MGM film Cabin in the Sky was a hopeful sign of increased media stardom for black performers, but race riots in the summer of 1943 placed a damper on movie theater managers’ desires to showcase them. Southern backlash against his appearances in mixed-race films made Hollywood film producers even more skittish of working with him.

In the postwar period, Anderson faced mounting approbation from critics who decried the prevalence of accommodating and buffoonish servant roles in the media and lumped Rochester among them. On Benny’s radio show, as the writers placed Jack in domestic situations and adventures outside the radio studio, he was brought into even closer contact with Rochester, and their relationship became, as historian Joseph Boskin noted, “extraordinary in its depth and sensitivity” and something “far beyond the typical employer-employee association.”4 Nevertheless, in 1950, Anderson would face outrage in the black community over the broadcast of a Benny radio episode awash in creaky old examples of Rochester’s Harlem debauchery, and frustration in trying to start a radio program of his own.

ANDERSON’S PRECARIOUS PERCH BETWEEN BLACK AND

WHITE WORLDS

Articles about Anderson in both the black and white press in the early 1940s dwelt on his economic and social success. They emphasized his lavish spending on cigars, clothes, a large house, cars, a boat, and race horses, one of which, “Burnt Cork,” he entered in the Kentucky Derby. The tenor of articles in the black press was prideful in these public displays of wealth. In the white press, stories betrayed more ambivalence that he might be appearing to act “above his station.” Reporter Earl Morris argued in a Pittsburgh Courier story that it was politically purposeful for Anderson to ostentatiously wear good clothes and drive fine cars; through his efforts, whites might now better tolerate black people’s economic success and increased participation in consumer culture. “He has subtly injected racial propaganda, been a sort of good will ambassador for his minority.”5

The price of fame in mainstream white American culture for an African American actor was enduring the many humiliations imposed on him, intentionally and unintentionally, by insensitive writers. In 1943, Anderson was one of the rare black celebrities to be the subject of a feature article in the Saturday Evening Post, one of America’s most widely read magazines.6 Author Florabel Muir patronizingly looked down her nose, sniffing that the suit Eddie wore was rumpled and that his pretentious twelve-room mansion located near Central Avenue was an exact copy of Benny’s house in Beverly Hills. A feature article on Anderson in the fan magazine Radio Mirror described him as “the eye-rolling eight ball.”7 Both black and white newspapers also downplayed Anderson’s talent and instead emphasized the debt that he owed to Benny for his fame. An Atlanta Daily World article by Ruby Berkeley Goodwin maintained:

Rochester, through the generosity of Jack Benny, was lifted from obscurity to stardom. I don’t mean that Rochester can’t stand on his own feet as a comedian. He can! But not in another fifty years will you find a man like Benny who will act as a stooge for Rochester. . . . I have nothing but the highest praise for Jack Benny. He doesn’t talk Americanism—HE LIVES IT!8

The black press emphasized the friendly, egalitarian nature of Anderson’s relationship with Jack Benny, in radio, films, and in real life, and Rochester’s ability to critique his employer’s actions with an attitude of equality that no other black character in film or radio was allowed to express.9 “Jack Benny and Rochester are what, in the old days of vaudeville, would have been called a team,” asserted the New Amsterdam News in 1943:

The relationship between Rochester and Benny is both classic (deriving from Carlyle) and democratic, in the American sense. Although Benny is no hero to his valet, neither is he a villain. And if Rochester, the gentleman’s gentleman, isn’t much of a help, neither is he a very serious hindrance. So, in effect the arrangement is a nice cozy one, in which the distinction between master and servant is practically non-existent.10

The article concluded, “The professional relationship between Benny and Rochester is a landmark in the history of the entertainment world, and a tribute to Benny’s astuteness.”11

Benny’s radio show even occasionally acknowledged how central Rochester was to the program’s popularity, such as on the April 2, 1944, program, when Jack was being interviewed for a story by Hollywood gossip columnist Louella Parsons. The rest of the cast used Rochester’s popularity as a way to puncture Jack’s overblown sense of his own talent:12

LOUELLA: How long have you been in radio?

JACK: Thirteen years.

LOUELLA: And of those thirteen years, how long would you say you’ve been a star?

JACK: Seven years.

LOUELLA: And how long has Rochester been with you?

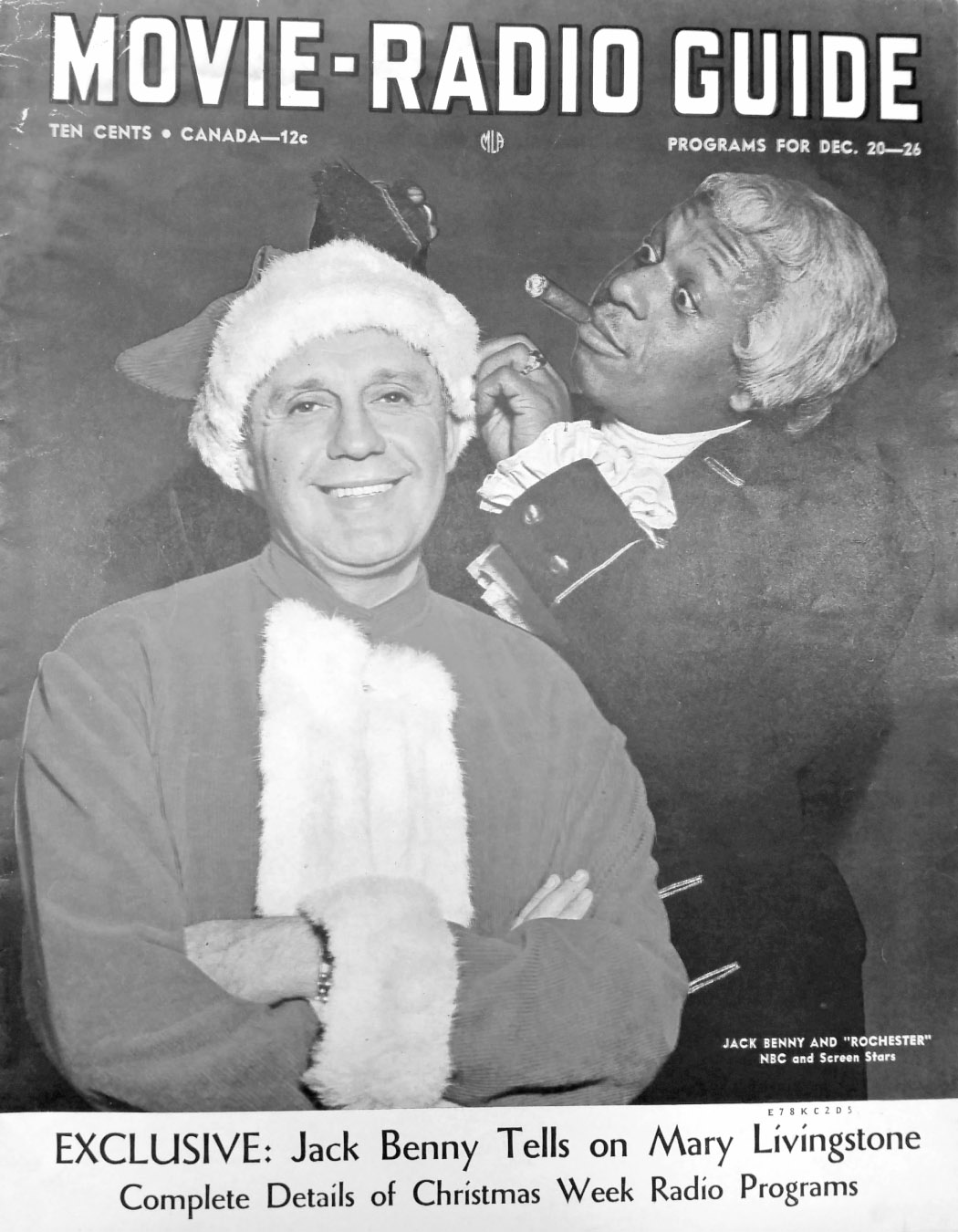

FIGURE 14. Eddie Anderson and Jack Benny parlayed their radio popularity into film successes. They were promoted as the first interracial buddies in American movies in the early 1940s, co-starring in Paramount films Man About Town, Buck Benny Rides Again, and Love Thy Neighbor. Movie Radio Guide, December 20, 1941. Author’s collection.

MARY (BREAKS IN, ARCHLY): Seven years.

JACK: Yes, he’s a wonderful butler.

PHIL: He’s pretty good on the radio, too.

JACK: Once in a while I let him take a line when I’m short an actor.

Despite utopian hopes in the black community that Jack Benny was a race relations hero, as Benny was honored with awards in 1941 for promoting interracial understanding and expanding opportunities for black performers, it was nevertheless still easy for him and his writers to slip into old attitudes. Puzzling out Rochester’s place in white-dominated society in a way that would provoke laughter from studio audiences and mainstream radio listeners, Benny and his writers thoughtlessly incorporated older racialized humor into the program that struck ambivalent notes about the idea of interracial progress. The writers occasionally incorporated blackface jokes into the show. Even in these scripted situations, Rochester was able to resist having to perform blackface routines and to argue that minstrelsy was no longer acceptable to him or the black community. On the February 11, 1940, program, Jack and the radio cast took a long automobile trip in the old Maxwell, traveling from San Francisco to Yosemite for a skiing vacation. While Rochester was driving them along, Jack required him to sing to provide some entertainment because the car lacked a radio. Rochester complained to Mary:

ROCHESTER: At eight o’clock, he wants me to imitate Amos and Andy!

JACK: Well?

ROCHESTER: I can’t do that blackface stuff!

JACK: You can try, you don’t have to be perfect. . . .

On the March 29, 1942, program, Jack led the cast in putting on an abbreviated version of an “old-fashioned” minstrel show.13 The cast joked about the burnt cork they would be wearing (and Rochester joked that he spent his make-up allowance on a bottle of gin with a cork in it). Unexplained raucous laughter erupted from the studio audience when Anderson came to the microphone; it could be that either he wore a costume or signaled by a gesture that he thought the performances absurd. Rochester did not have to take part in the ritualized minstrel humor, but was given a stand-alone feature role, singing “Somebody Else, Not Me,” a comic ballad made famous by Ziegfeld Follies entertainer Bert Williams.14 In one of the final references to blackface on the Benny radio show, on the February 27, 1944, program, Jack and the cast talked about seeing Al Jolson down on his knees, participating in a dice game. Jack compared Jolson to Rochester, remarking that they were just alike. Rochester retorted, “But after it rains, I’m still Rochester.” Such lapses of racial sensitivity would continue to sporadically erupt on the Benny show in the coming years, bringing increasingly strident complaints from black critics.

THE TALES OF MANHATTAN CONTROVERSY

His reputation in Hollywood having risen after his success in the three Paramount films, Anderson was offered several visible (if small) film roles that blurred the boundaries between his radio character and his identity as a media star. He appeared as the chauffeur in Topper Returns (Hal Roach Studio, 1941) with Joan Blondell and Roland Young and was pictured in the poster and lobby card advertising. He played a dancer in the Mary Martin–Don Ameche backstage comedy Kiss the Boys Goodbye (Paramount, 1941). In the variety show film Star Spangled Rhythm (Paramount, 1942), he danced and sang in a “zoot suit” specialty number. Through his popularity on the Benny radio show, Eddie Anderson also received invitations to make guest appearances on other broadcasting comics’ programs. Nearly all his roles limited him to the character of Rochester, however. He appeared on Fred Allen’s program in 1940, interviewed as Rochester on the “people you are unlikely to meet” segment, and Allen egged him on to tell secrets about Benny’s cheapness. He was on the Eddie Cantor program on June 24, 1942, in an episode noted by the Defender’s Harold Jovien as among best of the year.15 His guest appearance on Duffy’s Tavern in January 1943 was highly anticipated in the black press as a rare occasion for Rochester to trade quips with Eddie Green’s character of the black waiter, who was the only sane employee of that crazy establishment.16

In early 1942, Anderson landed a plum role, a part playing alongside Paul Robeson and Ethel Waters in a film production that featured a dozen prominent Hollywood actors, 20th Century Fox’s Tales of Manhattan. The anthology film’s plot concerned an actor’s tuxedo jacket, supposedly cursed, which fell into the hands of four different owners. In the final sequence, the tattered coat was tossed out of an airplane by gangsters. It landed in a Southern sharecropper’s field. Impoverished, naïve, and deeply religious farmers Paul Robeson and Ethel Waters, along with other laborers (played by members of the Hall-Johnson Choir), took the coat to their preacher (Eddie Anderson), and they found its pockets stuffed with $50,000 in cash. They collectively decided use the heaven-sent gift to purchase their farmland. The black characters were very stereotypically drawn, but the film was touted during its production as being quite prestigious, and it premiered to admiring reviews.17

When the film began playing a preview engagement in Los Angeles, however, on August 7, 1942, a group of ten young black journalists, led by Los Angeles Sentinel publisher Leon H. Washington Jr. and Los Angeles Tribune editor Almena Davis, picketed outside Loew’s State Theater. They marched with banners that shamed Robeson, Anderson, and the other black actors for appearing in the film, and claimed the closing scene was “fraught with ‘Uncle Tommism.’” The Defender reported that “members of the picketing committee stated the move against the picture was part of a general movement to discourage the making of pictures which obviously hold the Negro character up to ridicule and burlesque.”18

A front page essay by young California Eagle editor John Kinlock, published the same week as the picketing, railed against the prevalence of Uncle Tom characters in mainstream white media:

Ofays [slang term for whites] and people like that enjoy to consider Uncle Tom with their eyes slightly misty with crocodile tears and assorted cracks about the inhumanity of mankind during the lamentable period of slavery. . . . He is the kind of person who is always playing Jack Benny to some peck’s Rochester. He probably disseminates more affirmatives in one afternoon than the whole motion picture industry in the course of six months, which is saying a great deal, indeed. Once upon a time, Uncle Tom was an ancient character with little intelligence except an uncanny insight into what the Boss Man wanted him to do-say-or-think at any given time. The type of Joe who might utter “You sho’ is one GOOD white man, and kick me some mo’ please, suh, and sho’ laks you’ boot toe.”

Kinlock broadly charged all black performers who worked in Hollywood films and Los Angeles night clubs with enacting the new version of “streamlined Uncle Thomas.”19

The Hollywood black establishment was horrified at this public eruption of intragroup conflict and criticism. Rumors spread around town, to film producers and studio executives, that it was the actors themselves who had done the picketing.20 Eddie Anderson secretly gathered a group of the top black performers together to draft a statement distancing themselves from the protest.21 Uncle Tom charges continued to spread in the black press, however. A letter to the editor of the Defender from a Chicago reader queried in early September: “Why must Rochester, Sunshine Sammy and a few more of our male Negro actors continue to play right into the white man’s hands? Don’t these fellows realize that the parts they play are doing serious harm to their race? Their roles are used to depict the Negro’s lack of initiative, both mental and physical.”22

Walter White, national secretary of the NAACP, in February 1942 made a well-publicized trip to Hollywood to meet with studio executives, but not the established black actors, to advocate for more dignified representations of blacks on screen. White recommended the employment of new “serious” actors (like his protégé Lena Horne) who would forge new ground by refusing to play roles as servants and comic clowns.23 White issued statements from the New York NAACP offices supporting the Tales protests. Anderson and other members of the black acting community were frustrated at White’s neglect of their input and advice. The veterans claimed that these agitators from outside the acting community—the militant members of the black press and the NAACP leadership—were not supporting them, but trying to undermine their efforts, and replace them with other actors.24 The veteran actors worried that if they stood up and loudly protested, their careers would be affected, so they were reluctant to say negative things in public about the studio system.

In September 1942, the black performers released a further elaboration of their response to the Tales picketing, making public some of their behind-the-scenes efforts over the years to improve conditions for blacks in the film industry. “Colored actors themselves, without the aid of outsiders, have broken down former practices of segregated dressing rooms, studio cafes, washrooms and rest rooms, and accompanying signs that once were common, such as for ‘colored men’ or for ‘colored women.’ A large square black screen used by camera crews, formerly called the ‘n—r’ is now called the ‘gobo’.”25 Their statement detailed several of the most painful instances of racial insensitivity in film productions that they had been able to thwart in recent years:

Clarence Muse objected to the Nat Turner-like leader of a slave rebellion in Paramount’s So Red the Rose, [1935] humbly repenting and kissing the hem of his mistress’s dress. Director King Vidor said “All right Clarence, you rewrite that sequence yourself tonight, and we’ll shoot it tomorrow,” and it was done, while Margaret Sullavan the star got bawled out for objecting. Take Imitation of Life [1934] which catapulted Louise Beavers to fame. Although she was then an unknown, she told the Universal studio officials during a story conference that her people hated the word “n—r” which ran freely all through the screen story. Out it came, and the word “black” was substituted by director John Stahl. And then believe it or not, their eyes having been opened, they cut a whole sequence that depicted a near-lynching when Peola, pretending to be white, accused a young colored man of attempting to flirt with her. Just as they have strung him up, she breaks down with remorse and screams “Don’t do it, I’m a ‘n—r’ too”!

The actors’ catalogue of film production horrors climaxed with an incident involving the pair that readers might have been least likely to expect—Anderson, on the set at 20th Century Fox, where he was shooting the film The Meanest Man in the World, with Jack Benny:

There was a scene where Rochester was to be hidden in a woodpile. Benny was to call, “Rochester, come out of that woodpile.” But the famous comedian [Anderson] quietly explained that the inference of the old saying “n—r in the woodpile” would bring a laugh for the whites, but indignation from colored movie fans. “Yes he’s right, Eddie’s right,” said Jack Benny to the director, “better take it out.”26

The veteran actors claimed that their efforts had been going on long before Walter White began agitating for better representation of blacks in Hollywood films. The group claimed to be glad for his assistance, but more ambivalent about his lack of support for the actors who were already in the business. The black actors who had footholds in Hollywood were upset at being criticized for taking the roles; they claimed they would gladly play parts as bank presidents, but until Hollywood screenwriting and casting changed, or a black consortium could establish an alternative film studio, the actors were going to have to play the roles that existed, or see all black characters disappear from American films. Walter White did finally acknowledge some of the actors’ concerns, as he retold Anderson’s “woodpile” anecdote in one of his newspaper columns. Nevertheless the NAACP executive would continue to rail against the black community’s acquiescence to the status quo in Hollywood.27

Meanwhile, Anderson also had to negotiate his role as an entertainment industry spokesman for the U.S. war effort to the African American public. There was widespread dissatisfaction in the black community over the irony of being asked to fight fascism and racial oppression overseas when they were treated as second-class citizens in their own country. To win over a skeptical black population (and smooth tense race relations with whites), the government’s Office of War Information used black celebrities to make persuasive pitches to support the war effort. Like other stars, Anderson was regularly asked to volunteer to give radio speeches and make personal appearances at war bond sales rallies. On March 30, 1941, Anderson took part in a special broadcast put on by the National Urban League to encourage racial fairness in hiring practices in defense industry jobs in “The Negro and National Defense,” broadcast over the CBS network. His speech, which he presented as if Rochester was giving a “practice run” of it privately to the “Boss,” was geared to persuade doubtful whites of their paternalistic responsibility to deal fairly with the black community:

It seems to me that Mr. and Mrs. America have been so busy in this great program of national defense that they sorta overlooked one of their children. One who has always been a great fighter—loyal, conscientious, and willing to do his bit at all times. It seems that this child is having a little trouble convincing the principals and teachers of this great defense program that he should be in there too and that he could come with flying colors if only given a chance to. He knows that he is a Negro and is glad to be. But first of all, he is an American, so let him be an American. . . . They have scientists, inventors, philosophers, machinists, mechanics—and that’s something like me at the house, eh Mr. Benny? In fact they have almost every other skill that is known to man. . . . I realize the whole thing is just an oversight and I know that Mr. and Mrs. America have been so busy that they kinda overlooked the one son that they can put up against the wheel and rest assured that nobody can tell him anything else but push. So, Mr. and Mrs. America, give this child of yours a chance to make you just as proud of him today as you’ve always been in the past.28

Anderson’s popularity with white audiences made him a nonthreatening spokesman for black rights, historian Barbara Savage notes. By presenting his message in an entertaining way, he might have caught the ears of listeners who might otherwise tune out serious policy discussions. Response to the Anderson program in newspapers across the nation was very positive.

During the war, Anderson remained active in support for soldiers and homefront activities. He appeared with Benny in special comic segments of “Command Performance” recorded by the Armed Forces Radio Service (AFRS) to entertain troops around the globe. He also a frequent guest star on the AFRS program “Jubilee,” which featured skits and musical performances by black actors, singers, and orchestras.29 Anderson joined the steering committee of the Negro Division of the Hollywood Victory Committee, organized and led by Hattie McDaniel, to provide entertainments for black soldiers.30 In January 1944 he gave a show at Tuskegee Army Airfield.31 Anderson also invested in a parachute-production factory in Southern California, which would be staffed by forty black workers.32

1943—CABIN IN THE SKY, RACE RIOTS, AND

BUTTERFLY MCQUEEN

In early 1943, Eddie Anderson signed a lucrative deal to appear in five upcoming films, earning $25,000 for each one. He was offered his largest role yet, in the MGM black-cast musical Cabin in the Sky, adapted from the Broadway musical, which two years before had featured Ethel Waters, Dooley Wilson, and Katherine Dunham.33 Eddie took the lead male role of “Little Joe,” while Ethel Waters repeated her role of Petunia and newcomer Lena Horne played temptress “Georgia Brown.” Horne’s film career was blossoming as she was also appearing in the 20th Century Fox black-cast musical Stormy Weather (co-starring Bill Robinson) which would be released two months after the April 1943 release of Cabin in the Sky.34 Louis Armstrong, Rex Ingram, Butterfly McQueen, and other prominent actors also had small roles in the film.

The plot, a retelling of the Faust legend, opens with loose-living “Little Joe” getting shot over unpaid gambling debts. His devout wife Petunia prays for his soul. An angel and devil visit Little Joe and give him one more chance. The sensuous floozy Georgia Brown is sent up to seduce him, but Petunia’s fervent entreaties to the Lord ultimately win the day. Cabin in the Sky (like Stormy Weather) presented mixed messages in attempting to answer critics’ calls for better representations of blacks in film—it symbolized an increased black visibility in Hollywood film, but it was also filled with obvious stereotypes. Reviews of Cabin connected the film to the wartime government edict to attract more black workers to war production jobs to the unprecedented push to feature black performers in major film roles to serve as models of racial acceptance.35 MGM placed large advertisements for the film in both the white and black press, predicting wide success for it across the nation. But the film seemed more like a religious-tinged folktale fantasy than a drama with any connections to the realities and challenges of contemporary black life.36

Appraisals of Cabin in the Sky in the black press were mixed. Some reviews emphasized the benefits to interracial understanding, pride in the visibility of the black actors and praise for their performances. Los Angeles Tribune critic Phil Carter approved of Stormy Weather but disliked Cabin, claiming “its ideology was certainly as bad or worse than the worst examples of Uncle Tommism of 20 years of screendom.” Defender critic Rob Roy expressed frustration that Lena Horne flaunted the exposure of her undergarments while singing in the film, wishing that black actors could be allowed to act and be costumed in a more dignified fashion. He accused the film studios of playing down to Southern white expectations.37

The race riots that erupted in Los Angeles and Detroit in June 1943 and which spread across the nation to Mobile, Alabama; Beaumont, Texas; Harlem, and other places through the hot summer weeks, were due to racial tensions boiling over into violence, and not directly connected to release of these black-cast motion pictures. Tens of thousands of Latinos and African Americans had migrated to booming, overcrowded industrial cities in the North, Midwest, South, and West Coast. In Los Angeles, groups of young draftees, inebriated and bored while on weekend leave, encountered young Latino and black males wearing the extremely nonmilitary fashion of “zoot suits.” Soldiers and sailors accosted the young men.38 Clashes between young whites, blacks, and Latinos expanded into riots in Detroit and other cities as whites resented the blacks and immigrants who’d moved there to take war jobs, and the new migrants were frustrated with the racism and poor working and living conditions they continued to face. In three days of violence in Detroit, 34 people were killed, more than 400 injured, and property valued at $2 million was destroyed.39

In the midst of the race riots, from Variety’s entertainment-focused point of view, the expensive all-black musicals and interracial films that were being shown in urban centers were inevitably linked to the violence. The riots were occurring downtown in entertainment districts, and the big movie theaters were flash points for violence, or so writers in Variety feared. In June and July, Variety’s front page contained reports of the downtown damages and widespread closure of theaters, baseball parks, and other entertainment centers, and paired them with reassuring stories that Cabin in the Sky was drawing “extraordinary business” in the fifth week of its engagement at the Criterion theater on Broadway.40 Yet on June 30, Variety’s headlines also warned, “Hollywood Holding up Pix Releases in Which Whites, Negroes Mix,” fueling the fears of skittish film exhibitors and movie producers that these films were too controversial to play. “Many pictures with colored performers are being withdrawn from current release due to the race riots in various parts of the country,” Variety noted. “Those films in which Negroes are shown mixing with whites are being pulled especially in Southern territories. Scenes showing whites and blacks on the dance floor in Stage Door Canteen are to be deleted through the South and other spots where feeling is running high. Likely also the Ethel Waters footage in that picture may be severely trimmed for Dixie screenings.”41

Two weeks later, Variety reported that the film exhibition situation for these films had turned even grimmer, with local censors across the South “hacking scenes indiscriminately.” Newsreel footage of black troops in battle, Cab Calloway’s performance in Sensations of 1945, and Lena Horne’s scenes in Broadway Rhythm were being excised in Memphis and other Southern cities.

The Chicago Defender substantiated some of the distressing stories about how the fallout from race riots and conservative Southern resistance was impacting the box office success of these films. “Think Race Riots Hurt Negro Films,” proclaimed one worried observer:

Loss of millions of hours in manpower in Detroit during the recent race riot will be nothing compared to the loss suffered by the motion picture industry, is the startling information that has come from reliable sources. . . . MGM’s “Cabin in the Sky” was hailed as a sure money maker for theatres waiting their turn to play it, and encouraged by “Cabin’s” success, 20th Century Fox’s “Stormy Weather” was being eagerly awaited. But this feeling has changed, and there is fear that it will affect others on the market as well as several in production.42

In early August, a front page story in the Defender told of “an angry mob of white townspeople” in the small central Tennessee town of Mt. Pleasant who forced a theater manager to halt the showing of Cabin in a segregated theater that had been filled with white and blacks patrons, even though the exhibitor had checked with the police department before booking the film. Local interracial labor strife was cited by the theater manager as a contributing factor to the disturbance.43 Reaction from prejudiced white Southerners had also been more severe than the film companies had anticipated. The skittish Hollywood studios began to pull back on their commitments to showcase black performers. The “Myth of the Southern Box Office” was alive and well, operating through fears and rumors. The studios were allergic to political controversies that would keep audiences away from the box office, and local theater managers were always anxious to compromise on the side of Jim Crow to keep racist elements of their audiences at bay.

Jack Benny returned to the air in September 1943 after his summer hiatus from broadcasting (during which time he traveled across North Africa, performing for soldiers with a small USO troupe). He faced difficult challenges with his radio program. His two writers for the previous seven years, Bill Morrow and Ed Beloin, had left the program. The show’s narrative and ratings continued to drift downward into mediocrity. In order to inject some new energy into the program, Benny’s new writers tapped into Anderson’s tremendous success on the Benny radio program and in film to attempt to further expand African American roles on the program. Their ideas, however, did not blossom into a character with nearly as much comic potential or human interest as Rochester possessed. Thirty-two-year-old stage and film actress Butterfly McQueen was introduced on October 31, the fourth program of the fall season, playing a new character, Butterfly, who was introduced as Rochester’s niece. On this first appearance Rochester brought her to the broadcast of the Benny radio program to sit in the audience with him and laugh loudly at Benny’s lame jokes. McQueen used the high-pitched voice she had made famous in her role as Prissy in Gone with the Wind. On the Benny program, the writers made her character similar to Prissy—young, naïve, and not very smart. Butterfly asked stupid questions and prattled on about her boyfriend Jerome in the army, who kept misbehaving and running afoul of the military police. She did not reappear on the Benny program until late November, when Mary solicited Rochester’s advice on who she could hire to be her maid, and he suggested that he could get Butterfly to work for her.

Butterfly McQueen appeared on the Benny show in the role as Mary’s personal servant in every episode during December 1943. She was on three times in January, performing her duties ineptly and telling more tales about Jerome’s exploits, then her spots tapered off to every other week in February and March. Having made fourteen appearances, McQueen quit the Benny program in late May, two weeks before the end of the season. McQueen’s exit apparently was a surprise to Benny, who had rarely had an actor willingly walk away from the gravy train of association with his prominent program. In a legal document ending her contract, Benny maintained that the role had significantly boosted her career. He enjoined her from taking any similar part: “You are unwilling to continue to portray the role of a domestic servant of my radio program, although I have been and am desirous that you continue in that role . . . you will refrain from portraying a domestic servant on the radio for one year.”44 McQueen was diplomatic in talking of her time on the Benny show, once saying only that she “didn’t care for it . . . They seem to like only very broad comedy.”45 “I don’t mind playing maid parts occasionally,” she told a reporter from Ebony Magazine in 1946, “but I feel that I would be disgracing my race by always accepting parts as a menial to be not only laughed at but looked down upon.”46

McQueen perhaps had the last laugh, for she was able to land several other radio acting jobs that were better than “handkerchief roles,” as she referred to those servant parts. She briefly appeared on the Dinah Shore program, and then she portrayed Thelma, the addlepated president of Danny Kaye’s fan club, on Kaye’s comedy-variety radio show. McQueen’s part on this program was fulsomely praised by both Variety (which gave Kaye’s program a special award for racial amity) and the black press, because the narrative never delineated whether the character was black or white.47 In a 1976 Washington Post interview, McQueen claimed that she left Benny’s show because she had been promised that her character would be Rochester’s girlfriend, and therefore she was disappointed to end up merely as Mary Livingstone’s maid.48

1945: ANDERSON’S ROLES CRITICIZED FROM ALL SIDES

During the war, Benny and his writers continued to struggle with the problem of how to create radio shows that would appeal to the military servicemen attending their live shows, while the NBC network broadcast the shows to home audiences who might not appreciate the jokes that resonated with soldiers, sailors, and airmen. When it came to crafting dialogue for Rochester away from the domestic setting of Jack’s house, it too often seemed easiest for the writers to send Rochester on a spree. From Rochester’s earliest days on the Benny program, the cast’s trips to New York had presented radio script writers with the opportunity to have Rochester drink, carouse, womanize, and gamble with abandon in his favorite Harlem gin joints. Rochester’s excesses were also ripe fodder for humor at camp shows. Benny and his radio writers also assumed that the excitement-starved men at military bases where they performed would want to hear randy stories of Rochester’s louche behavior. But what Benny and his staff did not anticipate were the changing sensibilities of media and social critics in the black community, who demanded more than ever to have black characters in radio and films act like admirable citizens with positive racial representations. Comic material that was relatively acceptable on Benny’s program in 1938 was increasingly deemed offensive in 1945.

After four shows broadcast from in and around New York City (where Rochester raucously partied in Harlem), the Benny cast was back on the road. Their February 11 broadcast was made from the naval air station in Glenview, Illinois. Halfway through the episode, Rochester called Benny on the telephone from St. Joseph, Missouri, where he’d journeyed ahead of the rest of the cast to prepare for the next week’s program.

“Hello Mr. Benny, this is Rochester,” Anderson said, to typically enthusiastic applause from the military audience. Rochester complained that he had encountered financial trouble on the train because Benny had cut his travel funds a little too close for the trip. Rochester explained the he had stopped to purchase a pack of gum at the train station, and weighed himself, and when he went to purchase his ticket, he was exactly six cents short.

JACK: Well, it’s your own fault for spending money like that. What did you do then?

ROCHESTER: Well I got on the train anyway, and if it hadn’t been for the extreme kindness of some sailors, I wouldn’t have had enough money for my fare.

JACK: Why, did they lend it to you?

ROCHESTER: No, they faded me!

JACK: Rochester! Rochester! Do you mean that you started a craps game with some sailors?

ROCHESTER: Oh no, Boss! No! I didn’t start it. You see, there were seven sailors standing around in a circle discussing Einstein’s theory of relativity . . .

JACK: Uh huh . . .

ROCHESTER: Then someone dropped a pair of dice, and Einstein went A.W.O.L.

JACK: But Rochester, you didn’t have to get in the game.

ROCHESTER: I know, but one of the boys said “Shoot,” and even I couldn’t refuse that call to battle stations.

The audience, primed to hear Benny and his cast make jokes geared to the male-dominated crowd of sailors and airmen, laughed heartily at this humor. And most white listeners at home across the nation may have thought it was relatively typical behavior for Rochester, nevertheless it was a type he had exhibited less frequently of late. Black listeners and critics, however, were very upset by the references to gambling and carousing, and more than ever before, they protested it publically. A year before, a Chicago Defender commentator had complained, “It’s too bad that ‘Rochester’ comedian on Jack Benny’s program has had to resort to Uncle Tom tactics to stay on that program . . . this columnist could not in the least appreciate his crap shooting skit on Sunday’s program.”49 Now, however, that same critic sharply criticized the Benny program and Anderson in particular for his willingness to participate in humor that the critic found degrading:

We are sick and tired of Eddie (Rochester) Anderson making a fool out of Negroes by portraying the part of a craps shooter on his weekly radio program with Jack Benny. It seems Rochester would have common sense enough to tell his script writers that Crap Shooting and similar buffoonery are not typical of the better class of Negro citizens who are more concerned with winning the war than listening to clown tactics which he uses just to please white audiences. . . . If you disapprove of his crap shooting skits, write to Carl Stanton, 247 Park Ave NYC who handles the advertisements for Lucky Strike cigarettes.50

Prominent radio writer Norman Corwin encouraged black listeners to collectively raise their voices against such stereotypical representations. “Negro entertainers should be educated. Pressure should be brought to bear against Rochester. . . . Phone the studio, write letters, publish editorials! Make your protests known. It avails nothing to resent quietly. Go after everything that is caricature, bad taste, incorrect even at the risk of being excessive in criticism.” Corwin argued that most radio and film directors and writers created such offensive scenes as the ones on Benny’s program out of “unthinking . . . inherited ignorance,” and not virulent racism, and so they could be educated.51 Corwin’s critique, like others, blurred the lines between disgust with the way the Rochester character was written, and disdain for how Anderson portrayed him, which must have been painful for Anderson to read. The Pittsburgh Courier concurred with the critiques, and headlined an article “Negroes Object to Rochester’s Crap Shooting on the Jack Benny Show”:

The continuous week after week involvement of Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, ace comedian on the Jack Benny radio show, in a crap shooting episode has stirred up a storm of protest amongst Negro listeners of the program on the West Coast. The matter has become the foremost topic of conversation by persons in all walks of life from the man on the street to milady in the drawing room. General opinion is that Anderson is too funny an actor and comedian to have to read such outmoded and stereotyped lines to draw laughs.52

Anderson was not without his supporters in the black community. They claimed he was being unfairly saddled with blame for reading comic dialogue he did not write, about stereotypical faults that had been attributed to other groups. His old stage revue director Earl Dancer remarked in the California Eagle, “I’m inclined to disagree with those critics who label Rochester an ‘Uncle Tom.’ Other than his expression of ‘Boss.’ I think his brand of comedy is on a par with Abbott and Costello, Bob Hope or any other dispenser of good clean fun. Some way, somehow, Rochester always comes out on top in all verbal bouts with Jack Benny.”53 A Chicago-area reader wrote in to the Defender:

I, for one, don’t feel that Rochester is making a fool out of Negroes when I know there are as many white people who shoot craps as Negroes. There are certain neighborhoods where white fellows shoot craps out on the sidewalk. You read articles in the daily papers and hear jokes on the radio concerning white people shooting craps. I heard a white soldier being interviewed on the radio one evening. When he was asked how he spent his spare time. He answered, “Shootin’ craps!”

The reader judged Amos and Andy to be far more problematic characters than Rochester because all profits from that show went to whites, whereas Eddie Anderson at least earned a big paycheck for his comic efforts, no matter how questionable.54

Anderson himself had rarely spoken publically about the challenges he faced portraying a black servant on a white situation comedy radio program. During this East Coast trip, however (perhaps responding to the critical outcry about the Benny episodes, or approached because of the controversy), Anderson granted an interview to Phil Carter of the Baltimore Afro-American in February 1945. Carter pressed the actor for his opinions on what a black performer’s responsibilities should be in crafting positive racial representations. Anderson’s answers remained as noncommittal as possible. Carter wrote that he “stressed the point that an entertainer should ‘keep out of politics and must always appeal to all the people.’” The comic explained the narrow path he threaded between the expectations of different sections of his audience, and how loathe he was to step out of line or address contentious issues:

People take our broadcasts seriously. Sometimes they complain that Jack Benny doesn’t pay his singers enough or that he shouldn’t make some of his performers mow the Benny lawn. Some think I’m really his valet. Some of them write that he shouldn’t let me take such a bantering attitude. Others are surprised when I don’t hold his coat or dust him off when we are out together.

Carter noted that “as Jack Benny’s valet in the Rochester character, he has an off-handed, independent bantering attitude toward his boss.” “I asked him,” continued Carter, “what would happen if a real valet acted like that?” “It might not be so funny,” Anderson answered, but still the actor maintained that “I don’t portray an insolent character, just funny.”55 Carter questioned Anderson’s commitment to improving representations of blacks in entertainment. He argued that the comedy routines that Anderson performed live on stage during his summer tours, especially in black theaters in Harlem, Chicago, and across the South, contained an even heavier dose of jokes about razors, wild trips to Harlem, dice, and other stereotypes than were heard on Rochester’s radio sprees. “On the radio it appears that this is toned down by Benny,” Carter wrote. In concluding the interview, Anderson reiterated to the reporter that his audiences should not expect him to be a “race man first” and a comedian second. “I am in this business because I’m a comedian.” Reporters in the Pittsburgh Courier archly responded to Anderson’s refusal to be more proactively involved in cultural change:

The droll comedian was credited with having stated in an interview which appeared in an Eastern publication recently, that he was first, last and always a comedian given to humor and not solving the race problem. Interested observers here, however, point out that consciously or unconsciously, Negro actors and actresses of radio, stage and screen are ambassadors of either good or bad will for the entire race. This because of the dictates of American life, which thus far are still given to judging the entire race by the actions of the few.

After criticism from the black community, Benny and his writers in a subsequent show would usually provide some way to showcase Eddie Anderson, play up Rochester’s importance to the program, or bring on prominent African American performers whose close personal relationship to Rochester would be highlighted.56 Thus it might not be merely a coincidence that, soon after the Benny cast returned to Los Angeles after the long trip, the March 11, 1945, program’s theme revolved around Jack relating the tale of how he had supposedly met Rochester and brought him into the radio program “family.” In the story, Jack was driving his old Maxwell car in 1936 in New York City when he crashed into a taxicab that was driven by Rochester, who was employed by Amos and Andy’s Fresh Air Taxi Company. Rochester discussed Benny’s offer to settle the matter with his employers and the Kingfish, then they all trouped over to Benny’s hotel to try and wrangle a large damage payment. When Benny balked at even a $50 charge, Amos and Andy settled for turning over Rochester to Jack’s employment. Although audiences at the time may well have enjoyed the rare appearance of Amos and Andy (Gosden and Correll) on Benny’s show, listening to it today, the characters interact uncomfortably, the dialogue has not aged well and the dickering for Rochester’s services seems belittling.

Some observers in the black community saw this episode featuring Rochester to be Benny’s attempt to make amends with critics. The Chicago Defender’s columnist “Old Nosey” extended an olive branch over the crap shooting complaints of five weeks earlier. The reporter complimented Anderson and Benny on now offering a much more congenial depiction of Rochester:

We tip our topper to Rochester [and] this week place . . . [our] stamp of approval on the recent broadcasts of the Jack Benny show, starring Rochester and others. Last Sunday’s program was one of the best in Jack Benny’s long list of stellar entertainment and Rochester didn’t have to shoot craps and ridicule his race in order to get a laugh. Instead, bolstered by the fine humor and showmanship of Amos and Andy, the broadcast was such rip-roaring fun, the studio had to space in much greater time than usual for the applause and laugher of the studio audience. Keep up the good work, Rochester and Jack Benny, and you’ll both retain your reputations as Ace Comedians of the Air.57

FILM BAN ON THE ONE HAND, UNCLE TOM

CHARGES ON THE OTHER

No sooner had Anderson gotten past the furor in the black community over Rochester’s radio misbehavior, when another publicity disaster struck, coming from the opposite direction. In Anderson’s latest film, a remake of the forty-year-old comedy Brewster’s Millions (United Artists, 1945), he had a featured role as “Jackson,” a servant and handyman employed at the home of young military veteran Monty Brewster’s (Dennis O’Keefe’s) mother. Anderson received fourth billing, with his photo featured in all the advertising. He was the only minority actor in the film, and was shown in collegial relationships with the white characters. Anderson wore a suit, spoke with an educated vocabulary, and worked alongside the hero to help spend the money to meet the terms of Brewster’s inheritance. The film received average-to-good reviews in the major newspapers; the Los Angeles Times reviewer rated it “rich in laughs and well played by its cast of performers who seem to have caught the comedy tempo.”58

However, in Memphis, Tennessee, reactionary white leaders objected to the film. Instead of cutting out a few offending scenes, as they had been doing to musical performances by Lena Horne and others in films during the war, now they escalated to a complete rejection—Brewster’s Millions was banned by the City Board of Motion Picture Censors. Lloyd T. Binford, the chairman, stated that he and his board “considered it inimical to the friendly relations now existing here. We believe it presents too much familiarity between the races. It has Rochester (Eddie Anderson) in an important role. He has much too familiar a way about him and the picture presents too much social equality and racial mixture.”59

The Chicago Defender expressed outrage at the Jim Crow politics on its front page, excoriating the actions of Memphis mayor “Boss” Crump and Binford, and leapt to Anderson’s defense as a hardworking actor who had volunteered his time for the war effort.60 On the front page of Variety, Lillian Smith, author of the bestselling novel Strange Fruit, lashed out at the timidity of the Hollywood for not standing up more firmly to racism. “She declared the industry’s lack of courage, shown by its catering so easily to southern prejudice, is feeding racial bias.”61

Another Jim Crow limitation Eddie Anderson faced was his inability to be able to accompany Jack Benny on Benny’s prominent USO tours to perform for soldiers in North Africa, the Middle East, and Italy in Summer 1943, and the South Pacific in 1944. In May 1945, Anderson volunteered to do USO shows for the summer but insisted that he wanted to take along two white musicians from Phil Harris’s band. His request was denied.62 In August, actor Orson Welles, who had become increasingly active in working to improve racial tolerance and civil rights for black performers, took a stand against segregationist military regulations. Welles had recently been the emcee of an awards ceremony for a group called the Interracial Film and Radio Guild, which had honored Bette Davis, Eddie Anderson, Lena Horne, and the Warner Bros. studio for their efforts to promote interracial harmony. Welles chose Jack Benny as the focus of his campaign, publishing an “open letter” to Benny asking him to fight to have Anderson included in his USO tours. Welles boldly took Benny to task for creating the damaging racial representations that he and Anderson had propounded over seven years on the radio program and urged both Benny and Anderson to become much more involved in political action for civil rights:

Without meaning it at all, you and Eddie have been doing the Negro people a grave wrong. The gags about gin-drinking and crap-shooting are unusually good gags, and Eddie makes them sound hilarious, but through the years they’ve helped perpetuate a dangerous myth. You and I and Eddie know very well that Negroes aren’t chronically irresponsible stooges born to shine shoes and steal neckties. But Rochester is one of your most valuable comic properties and it’s Eddie’s livelihood. I’m not asking either of you to give up Rochester. I’m suggesting that you put him to work in a good case. You can undo all the harm you’ve done innocently at home by very deliberately taking him overseas. Sure it’s easy for me to sit here by my typewriter and ask you and Eddie to endure all the strain. It’s easy, but you and Eddie are the kind of men it’s easy to ask a lot of because you give a lot without taking any bows. Here’s a chance to give more.

African American servicemen in the field also were beginning to protest against the representations that they encountered in films and radio programs. “Our GI’s in South Pacific Fiercely Resent ‘Uncle Tom’ Roles,” wrote a correspondent for the New Amsterdam News, who poignantly described the silent exodus of black soldiers from camp theaters when they encountered servants in Hollywood films enacting stereotyped behavior. Eddie Anderson was one of their main targets as the most prominent black performer on the air, along with actress Hattie McDaniel, whose servant roles in films were being severely criticized by soldiers and sailors.63 Militant young members of the black press now published pointed accusations that earlier journalists had dared not make so boldly—“Rochester heads list of theatre, radio players we can do without,” wrote a columnist for the Baltimore Afro-American. Unlike Anderson, who apparently made no public response to any of these charges, Hattie McDaniel personally answered these negative letters from black GIs and published letters to the editor of various publications defending the humanity and compassion she tried to bring to these very limited film roles.64

Even Dr. Reddick, director of the Schomburg Center, who in 1941 had honored Anderson and Benny as leaders in promoting interracial understanding, now four years later publically proclaimed that Rochester was a detrimental character and buffoonish comic servant: “‘A stereotype conception,’ complete with ‘razor toting and gin drinking’; is the manner in which radio treats the Negro.”65

In 1946, media critics also voiced increasing complaints about the use of broadly stereotyped Jewish and other ethnic figures in radio comedy, along with continued reliance on minstrel-show depictions of blacks. A group called “The Writers Board,” in promoting racial tolerance, judged Benny’s show harshly: “Jack Benny gets a dud for his use of the dialect hot dog salesman in his program [Mr. Kitzel, played by Artie Aurbach]. . . . This character tends to hold up a nationality to ridicule, just as the Rochester stereotype makes fun of Negroes.” Jack Benny’s loyal supporters, such as Variety’s Jack Hellman, were very defensive about the charges:

What’s wrong with a clean characterization that makes millions laugh? If you were to ask Eddie Anderson (Rochester) or Amos n Andy what the reaction of Negroes to their delineation has been they’d show you stacks of fan mail from colored people praising their antics and even making heroes of them. . . .. It’s all fun—good, clean fun—and never have we heard exception taken.66

The postwar era was a mixed bag of personal success and continued frustration on many fronts for Eddie Anderson and other black performers who tried to carve out careers in broadcasting. The veterans of the Hollywood black acting community were finding even fewer film roles. In radio, Hattie McDaniel played the role of “Beulah” the housekeeper. Gosden and Correll used a somewhat larger number of black actors to play supporting roles on Amos ’n’ Andy. In July 1948, NBC attempted to create the first all-black cast primetime network radio program, a musical variety show to serve as a summer replacement for Dennis Day’s situation comedy. Originally titling the program The National Minstrel Show, NBC programmers filled it with stereotypical comedy routines (performed by Lucky Millender and Moms Mably). Pressure from the NAACP and critics in the black press convinced NBC to delay the broadcast, and change the show’s name first to Modern Minstrels, then to Swingtime at the Savoy. Although by August the program finally had some promise, with an appearance by rising star Ella Fitzgerald, the show never found a sponsor, and was cancelled after five weeks.67

Anderson remained the most prominent black performer on the radio. After critical outbursts about Rochester’s stereotypically minstrel-like behavior during the war years, furor over the character died down, at least public complaints in African American publications. Benny and his writers steered their scripts further away from racialized humor for Rochester, even as they increasingly involved the Rochester character into the situation comedy.

The new 1946 magazine Ebony published a feature essay in its third issue on black representation in network broadcasting, “Radio and Race.”68 “Radio is growing up in race relations. . . . Uncle Tom is doing a fadeout,” it optimistically asserted. While taking Anderson to task for his unwillingness to publically support civil rights measures, the article still noted that his radio character was becoming less offensive to critics. “Biggest name is radio today among Negro performers is Rochester, whose routines with Jack Benny are heard by 25 million Americans every Sunday night. Never notable for his racial consciousness, even Rochester has been mending his mike manners and steers away from razor and dice clichés of late.” Other black newspapers kept their focus on the new generation of younger performers (Dorothy Dandridge, Lena Horne, Nat King Cole) and largely left Anderson out of the spotlight.

A ONE-TWO PUNCH OF TROUBLE FOR ANDERSON IN

SPRING 1950

As 1950 began, longtime members of Benny’s radio cast, including Eddie Anderson, were optimistic that they could achieve wider broadcasting success. Several years before, Dennis Day and Phil Harris had fruitfully expanded their careers through popular spin-off radio comedy programs (A Day in the Life of Dennis Day and The Phil Harris/Alice Faye Show) that brought them additional income and professional prominence, and they and their talent agents were investigating what they might do in TV. Mel Blanc, who appeared regularly on the Benny show as well as in small roles on fifteen other radio programs, had been given his own situation comedy program, The Mel Blanc Show, which ran on CBS network radio for a season.69 An advertising agency was considering the creation of a radio situation comedy featuring Mr. Kitzel. Rochester’s popularity had many wondering when Anderson would have his own spin-off program.

Finally, in early February 1950, advertising executive Adrian Samish of the Dancer, Fitzgerald, and Sample ad agency worked up ideas for a radio program to feature Anderson.70 It was an unsettled time in network radio, however, as financial support of the largest sponsors was shifting to television. Daytime radio was still quite healthy, however, and its lower costs meant that smaller sponsors could be courted to invest in programs. New programs, however, had an uphill battle to fight for support, as sponsors tended to gravitate to programs with proven track records. Success of the daytime comedy The Beulah Show emboldened the Dancer, Fitzgerald, and Sample agency to advance its plans.

Samish faced problems getting the American Tobacco Company to allow use of the Rochester character in a spin-off. Their delays apparently scuttled a fascinating program idea that Samish pitched to the new potential sponsor (Franco-American canned spaghetti, a subsidiary of Campbell’s Soup)—a parody of currently popular detective mystery shows, to be tentatively titled “The Five O’clock Shadow.” With the Lucky Strike makers’ hesitations and limitations, Samish ended up proposing to Franco-American a fifteen-minute daily situation comedy, to be called “The Adventures of Rochester.”71

The program’s narrative focused on Rochester, living in a small apartment near Central Avenue in Los Angeles’s black district, interacting with his landlady and neighborhood characters. Given the wit, ingenuity, and intelligence of the Rochester character that brought such verve to the Jack Benny program, these sample episodes Samish produced are quite disappointing. The show was a pale imitation of Amos ’n’ Andy, with Rochester reduced to the role of gullible, naïve, stupid Amos. All the other characters took advantage of his trusting good nature, bamboozling and humiliating him as if he was the greenest rube just off the farm. Eddie Anderson found that he had very little control over the character he had worked so hard to create over thirteen years. Negotiations stalled, and plans for Anderson’s program dissolved.72

In late January 1950, while this deal was percolating, Anderson hurried by train with the rest of the Benny radio show cast to broadcast two episodes of their radio program from New York City. Writer Milt Josefsberg recalled a combination of problems upsetting their scripting routine—the train trip cross-country was rough, Benny and Mary Livingstone both caught colds, and the writers were ill as well. While Benny’s radio show episodes in early 1950 had been some of the sharpest and wittiest that the writers ever concocted, this week left them harried and out of ideas. On Thursday the troupe was still scriptless with Sunday looming ever closer. Josefsberg said that, amid the turmoil and lack of creative inspiration, “Jack’s personal secretary, Bert Scott, remembered a script that Jack had done in New York almost exactly ten years ago. A copy of this script was dug up, updated, and shoved in as an emergency measure.”73 The script Scott had excavated was originally broadcast on December 15, 1940.

The episode began with the standard routine of Don introducing Jack, who talked about his New York adventures and the cheapness of his room at the Acme Plaza Hotel. Soon afterwards, Jack complained to Mary, Don, and Phil about Rochester’s absence and the fact that his brown suit was missing. Jack threatened to fire his valet when he found him. In the second half, Jack found a telephone number to call in Harlem to attempt to locate Rochester. A man answered, announcing the Harlem Social, Benevolent, and Spare Ribs Every Thursday Club. He told Benny that Rochester had entered the club on one knee, and pulled everyone into a craps game. The fellow provided Jack with a second number to call.

JACK: Hello?

MAMIE: Hello, Mamie Brown, the sweetest gal in town talking.

JACK: Miss Brown, this is Jack Benny.

MAMIE: Oh oh . . .

JACK: I’m trying to get in touch with Rochester, Is he there?

MAMIE: He was here.

JACK: Oh, well, do you think he’ll come back?

MAMIE: In all modesty, I can guarantee that.

JACK: Well, when he returns will you please tell him to call my hotel . . . and you can also tell him I’m stopping his salary.

MAMIE: Oh, that ain’t gonna bother him. He now owns the building that houses the Harlem Social, Benevolent, and Spare Ribs Every Thursday Club.

JACK: Oh yes, I heard about that,. He wins from everybody, doesn’t he?

MAMIE: Yeah, when I opened the door and he came in on one knee, I thought it was a proposal.

Mamie Brown provided Jack with a third number where Rochester could be reached and, when Jack inquired if that was another woman’s residence, she claimed if so, she would cut Jack’s brown suit to ribbons. Finally Rochester himself telephoned Jack, and Jack demanded that Rochester not lie about the whereabouts of the suit, while Rochester prevaricated. Rochester also claimed he started on his spree after being frightened by a black cat outside Jack’s hotel. Jack sighed in frustration, “This happens every time I bring him to Harlem.”

“We had hardly signed off the air when the network’s switchboard lit up a like a computer gone berserk,” recalled Josefsberg. The writer claimed that “Jack, a gentle soul, was amazed at the unfavorable reaction. He remembered that when the material had been done ten years previously it had caused hardly a ripple.”74 While no mention of this contretemps was made in any of the major newspapers or in the entertainment trade press, the Chicago Defender’s front page headline blared, “Jack Benny Show Stirs Harlem’s Ire.” The Defender reported that “A storm of protest broke Sunday night over the Jack Benny show on the Columbia Broadcasting System for the American Tobacco Company. As listeners blasted a stereotype ‘Rochester in Harlem’ sequence, the NAACP, through acting secretary Roy Wilkins, wired a strong protest to CBS, and spokesmen for the network told the Chicago Defender that it was receiving many telephone protests shortly after the program Sunday night.”75 Wilkins’s telegram asserted that:

NAACP protests script material for Rochester on Jack Benny program February 5. All the old inaccurate and derogatory stereotypes were pulled out of the hat by writers who used knifing, woman-chasing, drinking, dice games and stealing of wearing apparel in skit. Most writers for radio long ago learned these situations are not typical of Negro life and are not likely to make friends and influence people among them for products sold by such means. CBS, Benny, Rochester and script writers are old enough in this knowledge to know better and do better.76

Benny, his writers, and the CBS network, in a probable attempt to make amends with angry black critics, and to stem the tide of this protest that caught them so unexpectedly off-guard, quickly invited the prominent black musical group the Inkspots to make a guest appearance on Benny’s next program (February 12, 1950). They showed up to Benny’s cheap Manhattan hotel room to sing a parody of their hit song “If I Didn’t Care,” rejiggered to serve as the middle Lucky Strike commercial. In this episode, Rochester was a busy professional valet, taking care of Benny’s personal business, and commenting wryly on Benny’s cheapness. He exhibited no more roistering around Harlem.

Nevertheless, angry responses from the black community kept coming. Furious Defender columnist Lillian Scott fumed that neither Benny, Anderson, sponsor, nor network would take responsibility for the offensive episode:

So round, so fully packed—so stereotyped and stupid; best describes the celebrated Jack Benny show last Sunday over the Columbia Broadcasting System for the American Tobacco Company. Mr. Benny—they call him a comedian! Didn’t miss a single one of the old gables about Negroes. Aided and abetted by Eddie “Rochester” Anderson who should have been named for Buda-pest or Grand “Coolie” instead of that nice Upper New York State town. . . . There was much buck or should it be Benny passing after the show. The Lucky Strike people said Benny was sole arbiter of the entertainment portion of the show, and CBS allowed as how Monday morning they hadn’t had enough protests to issue any formal statement. Personally we’d like to know just how listeners felt all over the nation. Drop us a penny post card or letter, Chicago Defender, 101 Park Avenue, NYC 17, willya? CBS didn’t say anything because it took for granted that not enough of us would care enough to bother telling them.

Scott claimed the sponsor’s slogan now meant “Lucky Strike Means Foul Treatment” and suggested that black listeners boycott the brand.77

Anderson planted a face-saving story with a friendly Defender columnist, who wrote in the same February 18 issue, “Maybe you’d like to know that Eddie ‘Rochester’ Anderson, whose lines on the Jack Benny program were criticized last week, objected to the script when he first read it but time would not allow its being changed.”78 Benny, too, tried to mollify the protestors, after his return to Hollywood on February 25, releasing a statement published on the front page of the Pittsburgh Courier, expressing “regrets . . . that his program had caused ‘ill feeling.’” Benny’s publicity manager Irving Fein denied that the show creators had intended any harm, and argued instead that racial minority groups were “inclined to be too sensitive” about comic representations of ethnic characters. “Rochester, who is usually portrayed as a hardworking valet, is entitled to shoot some dice and take a drink once every ten years,” Fein claimed, and acknowledged that “it was ten years prior to the 1950 incident that Rochester had portrayed similar characteristics on a New York-originated broadcast.” “Most Negroes liked the portrayal,” said Fein, maintaining that they protested not “against the portrayal but against the general practice carried on in the radio industry of presenting the Negro in same type of roles without offering any other regular presentations what would give balance to or counteract the regular stereotype portrayals.”79

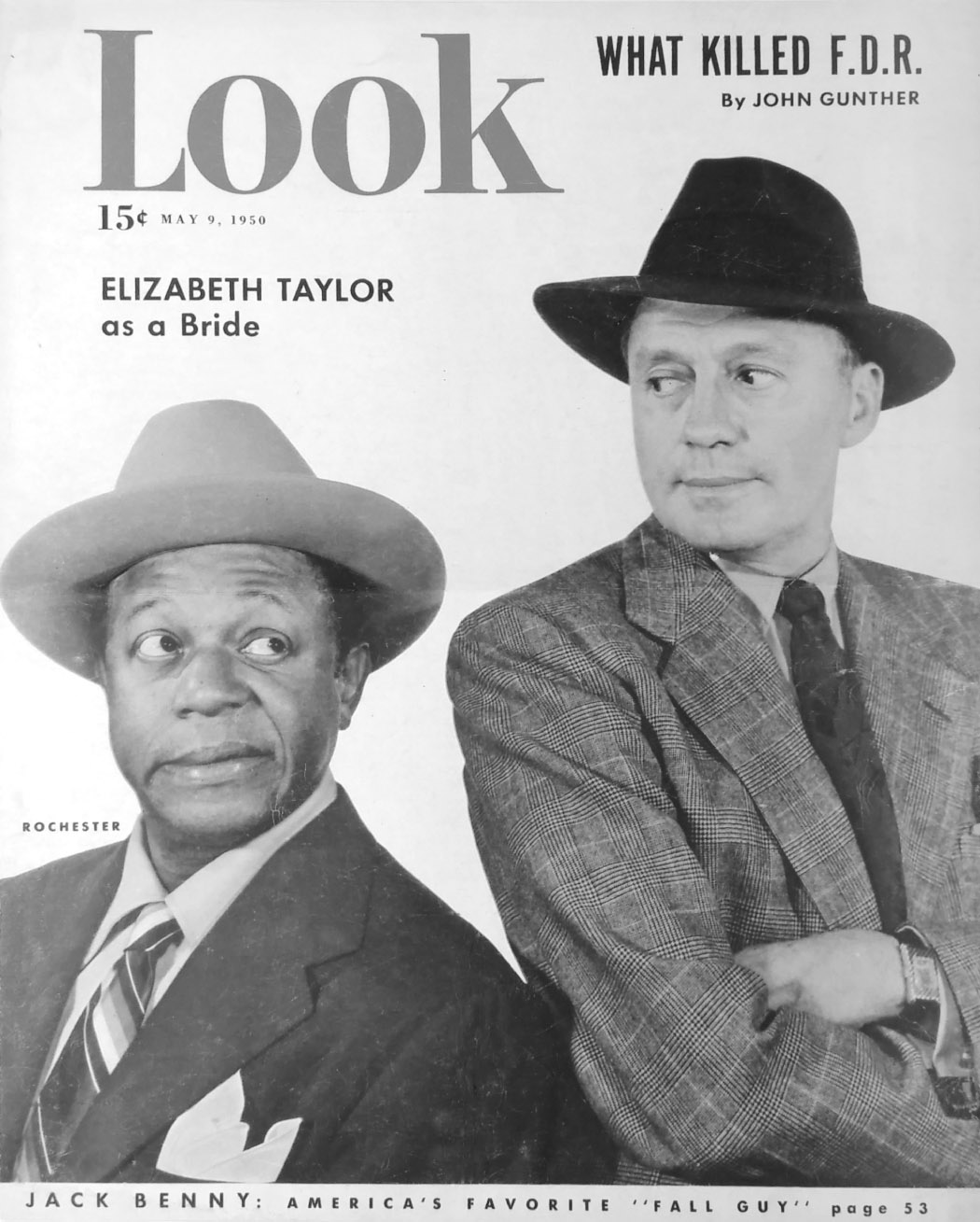

FIGURE 15. The pairing of Jack Benny and Eddie Anderson on the cover of Look magazine in May 1950 was touted in the African American community as one of the first nationally prominent representations of black celebrity and interracial equality. Look, May 1950. Author’s collection.

The same day, the Defender responded to the Benny’s mild excuses and the still-roiling controversy with an editorial, “When Racial Jokes Aren’t Funny:”

Many Negroes protested the recent Jack Benny radio show which had a Harlem sequence that featured some crapshooting, low brow characters who have been traditionally identified as typical Negroes. . . . To some whites, such protests seem unjustified and they insist that Negroes are too sensitive, too thin-skinned about this race and colored business. They point out that jokes are made about the Irish, Scotch and other national and racial groups and no offense is taken. These whites do not know what a Negro experiences when he tried so get a job or get a promotion in his position. If they did, they would understand why those racial jokes and clownish characterizations are not funny. . . . There is nothing funny about being a second-class citizen and being denied opportunities for economic and cultural advancement. We believe that there is plenty of material for humor that does not involve perpetuating stereotypes that impair our chances for getting out of the much created by bigotry.80

“Jack Benny certainly laid an egg, to use theatre parlance, with his recent broadcast about Rochester’s adventures in Harlem,” claimed the Los Angeles Sentinel.

Newspaper reports have it that Benny, his sponsors and CBS are all puzzled by the outbreak of criticism and each of them is protesting that no harm was meant. That’s probably true, just as it is true that the man who kills his friend with an ‘unloaded’ gun is sorry for the result. The trouble is that the victim is still dead in the shooting instance and that Negroes have been cast in a bad and unwarranted light by the Benny show.81

After being denied a radio program of his own, and being lambasted by black media critics for the “throwback” New York radio episode, Anderson received one small bit of positive publicity, his photograph in color on the cover of LOOK magazine’s May 9, 1950, issue. Benny and Anderson were paired looking quizzically in opposite directions of each other. (The cover accompanied Leo Rosen’s article “Jack Benny: the Ultimate Fall Guy.”) The Atlanta Daily World and Los Angeles Sentinel lauded it as a sign of positive interracial public relations, the World noting, “Rochester, radio aide to Jack Benny, graces the cover of the current issue of LOOK magazine which appeared on the newsstands here this week. This marks the first time from the information obtainable that a Negro has appeared on the cover a multi-million circulation magazine.”82 This accolade was overblown, as Anderson had been depicted on the cover of Liberty magazine in 1942 (with a hatchet, trying to dispatch a large Thanksgiving turkey), and Jackie Robinson had appeared on the cover of Time in 1947, and would be pictured on the cover of Life (albeit in black and white) the very same week as Anderson’s cover.83

ROCHESTER ON TELEVISION, AND HIS LEGACY

Eddie Anderson would continue to play a key role in Benny’s situation comedy narrative on radio and television for the better part of the next fifteen years. Rochester was the first major cast member introduced on the inaugural 1950 TV program, showcased in a sketch that featured him singing and dancing while cleaning Benny’s home and bantering with Polly the parrot. As Mary Livingstone and Phil Harris appeared on the show less frequently, Rochester became an even more central character in both the radio and TV show’s narratives. Jack and Rochester interacted at Jack’s home more frequently like household partners, and more than ever, Rochester had the dialogue lines that punctured the Boss’s outsized ego. Media historian Donald Bogle has characterized them as television’s original interracial Odd Couple.84

Anderson appeared with Benny on nearly all the 250 Benny radio episodes between January 1949 when the program moved to CBS, through its last episodes in May 1955. Television was a different matter. Anderson appeared in only half of Benny’s TV programs between fall 1950 and spring 1955. Even the Defender noticed that Rochester was being used significantly less on TV than he had been on radio.85 In the next four years of the show’s sponsorship by Lucky Strike, however (1955–1959), Anderson was on much more often—about 80 percent of the shows. In the following three years (fall 1959 to spring 1962) Anderson’s nagging health problems were probably a reason why he was reduced to appearing on only half of these shows, and only in a quarter of the TV programs between fall 1962 and spring 1965.

Criticism surrounding black representation on early 1950s television centered on Amos ’n’ Andy and Beulah. At the time, black media and social critics were also concerned about the inappropriateness and detrimental qualities that the Rochester character posed for beneficial representations of black manhood to U.S. media audiences. But for a number of reasons, Rochester and Eddie Anderson were not as targeted as often for protests and calls for the cancellation of Benny’s show. One factor must have been Jack Benny’s power as a leading entertainer. It would ultimately be his decision (with the sponsor having a big say, too) if Rochester would stay or go. A second reason would be the importance and value of the Rochester character to the Benny show. On television, Rochester emerged as the most prominent character who talked back to Jack, criticized his poor decisions and cheapness with smart jokes and witty retorts, and who interacted with him most regularly. The longevity of Rochester’s relationship with Jack, and the fact they were played by the same actors for all those years, also contributed to make them a taken-for-granted part of the media landscape. Anderson’s performance as Rochester—the amazing voice, sense of timing, skeptical wit, and charm that Anderson brought to the role—undercut many of the dialogue lines he was given that resembled Uncle Tom stereotyping. The fact that he was just one part of an ensemble cast, and not the title character, also perhaps kept him from being a lightning rod for criticism.

• • •

Largely, the Rochester character successfully negotiated the cultural and political tensions of 1950s broadcasting and popular culture. Benny’s scriptwriters could nevertheless still unthinkingly manage to create awkward situations on the program, such as when Rochester’s friend Roy appeared on radio episodes (one or two a year between 1949 and 1954). There was one in particular where Roy had been assisting Rochester in cleaning up the dishes at Benny’s home after a party (January 18, 1953), and Benny jokingly bantered about how little he intended to pay Roy. When Benny behaved this way, to a worker who had not been rude to him like the store clerks or waitresses he encountered, then suddenly it was not the old, joking penurious relationship that Rochester complained about, but something meaner.

When UCLA sociology graduate student Estelle Edmerson conducted interviews in 1953 for her thesis research, examining the difficulties faced by African American actors in network broadcasting, and the many limitations placed on representation of black characters on radio shows, criticisms of Eddie Anderson and the Rochester character remained a significant issue.86 In an era of reduced activity for black performers, Anderson was still the most prominent and best paid black star in broadcasting with the longest tenure on the airwaves. Yet Edmerson found Anderson to be as frustrating to interview, and as evasive in his answers, as had any previous investigator had experienced:

Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, actor on the Jack Benny show, answering the question relative to his problems as a Negro in radio, said that he had had “none.” “Rochester” commented on the Negroes’ criticism of the Negro actors’ radio presentations, he, evidently, did not feel that the criticisms had been a problem for him, even though his role as Rochester had been severely criticized by many Negro groups and newspaper columnists. . . .