Jack Benny’s Intermedia

Juggling of Radio and Film

After spending three months in the American film capital, interviewing 500 visitors from all walks of life, in January 1937, British journalist Austin J. Putnam completed research for his (apparently never published) book, Hollywood Tourist. Based on his survey, as he told a Variety reporter, Putnam compiled a list of “The Seven Wonders of Hollywood.” Most choices embodied popular fascination with the personalities and playgrounds of the West Coast film colony—Clark Gable and Shirley Temple, the Brown Derby restaurant, Charlie Chaplin’s film studio, Grauman’s Chinese Theater, and the Hollywood Bowl. Putnam’s number one, single greatest Wonder of Hollywood, however, was Jack Benny and the live productions of his radio programs. “More tourists asked me how they could get tickets to Jack Benny’s radio broadcasts than any other event. It is positively amazing the hold this droll comedian has on the United States public,” marveled the Englishman. “He is the most popular celebrity in Hollywood. . . . I enjoyed his show at the NBC studio more than any stage play I’ve ever seen in London or New York.”1

Indeed, was Jack Benny a movie star who appeared on the radio, or a radio star who made movies? A 1937 Los Angeles Times article pondered the question, noting that half of his income came from each medium, and that his intermedia stardom was shared by a growing number of multitasking celebrities, from Bing Crosby and Eddie Cantor, to “Arkansas Traveler” humorist Bob Burns.2 When asked which was the easier profession, acting in radio or film, Benny gave a purposefully ambiguous reply. The manner in which each medium structured his performance was the issue. Benny declared that “picture making is tougher,” noting that, unlike in radio, the actor couldn’t carry the script into the film scene to do dialog. Mistakes performers made while broadcasting live on the radio could be considered funny, but mistakes ruined a film scene. Films demanded perfection. On the other hand, however, radio brought with it the time pressures of creating weekly programs.

[I]n movies you only memorize a few lines at a time and stand under the hot lights for a few minutes. In radio a comic must work fast and keep up with the rewrites. You have to physically express emotion with body more than just voice in the movies; you have to do physical stunts rather than the sound effects man. On radio you can look like anything and dress casually, in the movies you must be handsome and have a good appearance.

Benny concluded, “I think for the time being I’ll continue to take a helping of both—and maybe a few personal appearances on the side.”3

Benny thoroughly embedded his radio career, and his radio program’s narrative, in the milieu of motion pictures. This intertwining of rival media forms brought both positive and negative reactions from the radio and film industries. In 1934, a time when most network radio programs were broadcast from New York City, Jack Benny’s top-rated radio program regularly emanated from Los Angeles, three years prior to primetime radio’s “Swing to California.”4 Like a funhouse reflection of the popular dramatic radio program Lux Radio Theater that brought a carefully constructed version of Hollywood glamor to radio listeners, Benny’s show drew on, magnified, and critiqued listeners’ fascination with the movies and Southern California.5 The feature films in which Benny starred in the late 1930s also just as thoroughly mixed radio and cinema. His movie stardom owed much more to his radio popularity than to his acting skills or the aesthetic quality of his film productions (with Ernst Lubitsch’s 1942 To Be or Not to Be the exception). Benny himself roundly disparaged his own film performances. Although they are not remembered as critical triumphs, several of his films were box office hits and boosted Benny (albeit temporarily) into the pantheon of top ticket-selling movie stars. Examination of Benny’s intermingling of radio and film in the 1930s expands and complicates our understanding of the many formal and informal ties between two commercial media forms, which were said to be bitter opponents in that era.

Contemporary media studies have tended to assume that media convergence—the synergizing of television, film, the Internet, advertising, gaming, and publishing into multimedia conglomerations that share narrative threads, producers, performers and audience interaction, and that create multidimensional experiences—is a recent phenomenon of industrial production practices and marketing imperatives.6 Jack Benny’s career in the 1930s provides a historical case study of the struggles and success of a convergence media star in an age when radio, film, newspapers, and advertising were (for the most part) separately operated, rival industries. Michele Hilmes and other media historians have examined how, behind all this anxious bluster, beneath-the surface commonalities and under-the-table negotiations worked to keep these separate entertainment media cooperating, “sharing talent, technology, aesthetics and business practices for decades,” finding commonalities and purchasing stakes in each other’s fields across the twentieth century.7

As Hilmes writes, Hollywood in the 1930s functioned “as broadcasting’s alter ego, its main rival and contributor, the only other force unified and powerful enough to present a viable alternative definition to the uses made of the medium by established broadcast interests, yet a necessary contributor to broadcasting’s growth and success.”8 The “interrelationship” and “intra-industry conflict” she examines between the film and radio industries looks somewhat different from the perspective of performers and audiences. What film audiences, radio listeners, record buyers, and readers of newspapers and magazines experienced in their everyday media consumption was not necessarily entirely separate media worlds, but more often an entangled flowing-together of entertainment, led by the performances of multimedia stars across all these production forms. Benny often acknowledged his media industry boundary crossings and thus fueled even higher levels of cross-media identification with his fans.

For listeners across America, Jack Benny’s radio program was an embodiment of Hollywood film culture that deepened audiences’ familiarity with the movies and encouraged Southern California tourism. From the very earliest Benny radio appearances in 1932, his scripts were filled with punning references to current film releases and stars. Benny’s radio programs in the 1930s featured at least fifty skits parodying recent box office hits, from Grand Hotel to The Women. As the decade progressed, Benny’s radio program added jokes about the directors, producers, and studio moguls whom Jack worked with in pictures.9 Story lines regularly featured backstage activities at the Paramount film studio, where radio listeners heard him whine about the small dressing room he’d been given and undertake disastrous attempts at film acting. His humor deglamorized the movie business, while still maintaining that everyone in Hollywood felt superior to the mere radio performer. Jokes about Jack’s vanity and stinginess often involved motion pictures, too, as he insisted on seeing his films again and again, fretted about matinee ticket prices and free theater passes, and dodged insults from Mary about attending screenings of his own films at movie theater Dish Night giveaways to get a free plate in the bargain.10 Benny’s broadcasts helped further cement film’s place, as well as radio’s, in a nationwide “imagined community” of shared everyday cultural experiences.11

Despite the potential benefits of cross-promotion, other factors inhibited Benny’s ability to mingle references to radio and film and to move between these competing mediums in the 1930s. The jealous rivalries of the separately owned media, each afraid of losing their audiences to the other, the interference of program sponsors who feared giving publicity to competing products, the contentious relationships between film producers and local film exhibitors, and between network radio and local radio stations, and between radio and local newspapers, all threw up challenges to Jack Benny’s intermedia promotions.12

HOLLYWOOD CELEBRITY—THE CORE OF BENNY’S

VAUDEVILLE AND RADIO ROUTINES

Like other major stage, vaudeville, and musical performers of the early 1930s (such as Eddie Cantor, Al Jolson, Ed Wynn, Fred Allen, Will Rogers, Bing Crosby, and Fred Astaire), Jack Benny explored options for his career in a variety of entertainment media during a time of technological change and economic upheaval. Benny appeared in narrative feature films, variety-show-style revue films, comedy film shorts, Broadway shows that mixed scantily clad showgirls with comedy routines, vaudeville turns, and guest appearances on various radio programs. Separate entertainment media forms were converging and mixing, some suddenly blossoming while others were declining, and a savvy group of performers dipped toes into many mediums, trying to ascertain which streams were drying up and which might flow toward continued success.13

After his well-received appearance as master of ceremonies in MGM’s first talkie The Hollywood Revue of 1929, Jack Benny increasingly interpolated references to Hollywood personalities, current films, and his own exploits in the movie industry into his vaudeville humor. Al Boasberg, who had scripted the dialog for the film, wrote Benny a routine concerning his experiences in Hollywood working at MGM. It connected to core aspects of the classic Benny character and style—it was a mixture of urbanity and sly, self-denigrating humor that enabled him to belittle his manhood and poke fun at his unsuccessful attempts to become a leading romantic actor. It shattered any pretentions he might present that he was a debonair movie star who would appropriately be co-starred with Greta Garbo. It assumed that audiences were familiar with his work in films, and for much of its topical humor it drew upon vaudeville audiences’ broad interest in the movies.14

Benny’s earliest appearances on radio also linked him to the film world. In October 1929 he was on a program broadcast from a California station in connection with MGM’s promotion of the Hollywood Revue. Benny also guest starred on an episode of NBC’s RKO Theater of the Air in September 1931. Jack Benny was supported in these endeavors by the Hollywood film studios, which Michele Hilmes notes made major programming, publicity, and ownership forays into radio broadcasting as “talkies” connected film much closer to other recording, music, and Broadway theatrical industries.15 When Benny had a brief guest shot March 29, 1932, on Ed Sullivan’s New York City–based radio program,16 (an appearance he referred to in subsequent years as his first big break in radio), Benny opened with a self-deprecating greeting that played up the intimacy of his entering American homes: “Ladies and Gentlemen, this is Jack Benny talking. There will be a slight pause while you say, ‘Who cares?’” The rest of Jack’s three-minute talk was drawn directly from the Garbo vaudeville monologue:

I am here tonight as a scenario writer. There is quite a lot of money in writing scenarios for the pictures. Well—there would be, if I could sell one. I’m going back to pictures in about ten weeks. I’m going to be in a new film with Greta Garbo. They sent me the story last week. When the picture opens, I’m found dead in the bathroom. It’s a sort of mystery picture. I’m found in the bathtub on a Wednesday night. I should have been in Miss Garbo’s last picture but they gave the part to Robert Montgomery. You know—studio politics! The funny part of it is that I’m really much younger than Montgomery. That is, I’m younger than Montgomery and Ward. You’d really like Garbo. She and I were great friends in Hollywood. She used to let me drive her car all around town. Of course, she paid me for it.17

Benny reused this favorite Garbo bit several times on his early radio shows, particularly when he changed sponsors and was introducing himself to audiences in a new time slot.

Deprecating his own film career as an entrée to making humorous comments about Hollywood remained a staple of the comic routines Benny and his script writer Harry Conn crafted when Benny began his radio broadcasts for Canada Dry, although NBC was touchy about allowing him to mention that his film studio was MGM, because that would be advertising without payment. Benny and Conn liberally sprinkled the Canada Dry show scripts not so much with radio-themed humor but rather with movie-related jokes (such as claiming he worked as assistant lover to Ramon Novarro, and that he had dated Peach Pitts, sister of scatterbrained film comedienne Zasu Pitts).18 As he had in his earlier vaudeville performances, Benny incorporated discussion of his real moviemaking activities into the radio dialogue, to add a sense of personal connection to his audiences. Working discussions of his other media activities (film shoots and live stage appearances on tour with his radio cast) into his radio dialogue also helped promote all these various endeavors.

A recurring skit in the Benny radio program’s early years featured Jack reporting as the “Earth Galloper,” a gossip columnist who loosely parodied the broadcasts of Walter Winchell, whose career had blossomed in 1932. Benny’s “Earth Galloper” continually made joking references to the sizes of Garbo’s feet and Clark Gable’s ears, and the onscreen romantic prowess of Mae West and Maurice Chevalier. Celebrity quirks seen in the newsreels were also fodder for Benny’s topical humor, such as George Bernard Shaw’s long beard and Mahatma Gandhi’s loincloth. The Benny show’s humor revolved around demystifying fame and humorously acknowledging radio listeners’ interest in Hollywood gossip.19

Benny’s fully formed radio persona began to emerge in skits in 1934 that concerned Jack’s unsuccessful struggles with his film director to make his part larger or to avoid having his love scenes cut out. Jack’s filming of Transatlantic Merry Go Round (RKO, 1934) was the inspiration for the funny and effective radio skit broadcast about his film screen test, in which Jack spectacularly flopped as a romantic actor.20 Even greater discussion of Jack’s movie career in his scripted radio exploits came after Benny’s move to Paramount studios in 1936. Sometimes the radio program’s narratives involved the show cast visiting Jack at the studio and discussing the deficiencies of his dressing room (which was often merely the men’s lavatory or a broom closet). Jack rehearsed an upcoming love scene (which would not actually appear in the film) with either his filmic leading lady (Joan Bennett), or with Rochester taking Joan’s role. Jack was depicted as a terrible movie actor who continually muffed his lines. At other times, Jack (with Mary tagging along to witness his embarrassment) waited in vain in the outer offices of a real-life film director or studio executive who would not even deign to meet him. In 1937, when Benny was filming Artists and Models at Paramount, he and his writers (Morrow and Beloin) began to incorporate an even more direct references and connections to his movie-making activities into the radio show’s narrative. This demonstrated strengthening cooperative intermedia ties between Paramount, NBC, ad agency Young & Rubicam, and sponsor General Foods.

Another effective way that Jack Benny and Harry Conn incorporated references to Hollywood and film culture into their radio show came from lampoons of recently released movies. Benny and Conn asserted that they were the first to create film parodies on radio, but others were experimenting as well—Ed Wynn was lampooning the librettos of popular operas and many of Eddie Cantor’s comic sketches were film related. The parodies began in the early months of the Canada Dry program in 1932, when the cast performed several ten-minute take-offs on MGM’s 1932 all-star melodrama Grand Hotel (dubbed “Grind Hotel”). The sketches were so popular that they were reprised several times on the program over the next two years. As the dashing Baron (a character played on film by John Barrymore and on radio by Jack) and tragic, reclusive ballerina Grusinskaya (Garbo’s film role, played by singer Ethel Shutta in the radio skit) pursued a surreptitious romantic rendezvous in her hotel room, the dying accountant Kringelein (bandleader George Olsen taking Lionel Barrymore’s scenery-chewing role) ran about shrieking that he only had five minutes to live. Nearly dead Kringelein became something of a recurring character, adding extra absurdity to the Benny radio troupe’s antics in the subsequent months.

In the next years, the Benny radio cast performed at least fifty hilarious take-offs on films such as I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, She Done Him Wrong, Little Women, Dinner at Eight, The Barretts of Wimpole Street, Charlie Chan at Radio City, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, The Count of Monte Cristo, The House of Rothschild, Mutiny on the Bounty, and The Women. Sharp writing and bountiful comedic skills were required to make the parodies funny, and their success rested on a substantial audience familiarity with the film, titles, characters, and stars. The skits also benefitted the radio show, providing useful alternatives to the increasingly stale vaudeville jokes that other comedians clung to. In a 1934 interview in the San Francisco Call, Benny commented: “Our humor is getting more subtle. The change came, I suppose, with the introduction of true satire on the air, with which I had something to do. We began kidding current pictures and plays, giving the comedy a crazy impromptu style. In radio work you can’t stand still.”21

In the mid-1930s, several new radio programs debuted that featured dramatic adaptations of recent Broadway plays and films for radio, adding more intermedia connections for radio listeners and more spark for Benny to contrast the humor and absurdity of his skits with the seriousness of these other productions. Louella Parsons’s radio program Hollywood Hotel, on the CBS network, incorporated twenty-minute preview vignettes of new movie releases into the program’s production, often featuring the film’s famous performers. The Lux Radio Theatre program, which became the most prestigious dramatic series on network radio by presenting well-crafted adaptations of Hollywood films and featuring movie star performances, began broadcasting on the NBC Blue network in 1934. The program, originally based in New York, featured adaptations of Broadway dramas, before switching two years later to programs based on film dramas, in a show produced in Hollywood on the CBS network and hosted by famous movie director Cecil B. DeMille. The popular program most often focused on melodramas, offering only a few adaptations of comic film fare.22

Benny’s parodies of recent movies also served as useful promotional publicity for the targeted films and stars. Benny assumed that the film studios would welcome these efforts, but such was often not the case. Benny, his writers, advertising agency handlers, and network bureaucrats had to obtain written permission from the movie studios to use the titles, characters, and any dialogue or plot elements from a film. Original authors and the film studios yelled when too many spoilers were revealed, or when the humor was subpar. Eugene O’Neill withheld permission from radio programs after a few lousy takeoffs on his plays, but allowed the Benny cast to attempt Ah, Wilderness. Movie theater owners across the nation continually begged the film studios not to allow radio adaptations of current films to give away too much of the plot, the climax, or conclusion, for fear it would keep too many of their local clients home from the theaters.23 Film studios grouched about Benny dragging out parodies of Anthony Adverse and Tom Sawyer over multiple episodes.24

To avoid giving away too many details, the Benny movie parodies had only the most tenuous connection to the actual film they caricatured. The skits would focus on the star personae in lead roles (often substituting the star name for the character’s name). After establishing the leading stars and/or characters and setting, soon these parodies shifted away from any connection to the film toward vaudeville-style jokes about illicit extramarital affairs or verbal slapstick absurdity. This tactic generally mollified the film studios, but Benny would face trouble in the early years of television when he performed his takeoff on Gaslight, which he had first done on radio October 14, 1945, with original star Ingrid Bergman. Benny reprised the sketch on live TV January 27, 1952, with Barbara Stanwyck, but when he and his production staff sought to do it a third time, capturing it on film in June 1953 (again with Stanwyck) for TV in a skit titled “Autolight,” MGM had clamped down and would only give permission for current releases to be skewered. Benny performed the episode anyway. MGM sued and blocked the show from being aired. MGM, Benny, and CBS sparred in a multiyear law suit over the creative limits of parody, CBS appealing the case all the way to the Supreme Court. The court found that Benny’s parody was too similar to the original film.25 Finally, Benny paid to license an adaptation of the film and aired his sketch in 1959.

For all the movie talk, however, in the 1930s, Benny’s radio program rarely included guest star appearances. Only Andy Devine, the jocular, rusty-voiced movie cowboy, appeared regularly between 1936 and 1938, participating in “Buck Benny” Western parody sketches. Robert Taylor appeared once in 1936, and Joan Bennett (Benny’s co-star in Artists and Models Abroad) made two appearances. The stars would only start shining more frequently on Benny’s program at the end of World War II, when Ronald and Benita Colman led the way. Benny’s radio and TV programs would then be known as shows that were protective and kind to stars—Humphrey Bogart, Jimmy Stewart, Claudette Colbert, and Marilyn Monroe would make rare broadcast appearances with Benny.

BENNY’S CONTRIBUTIONS TO HOLLYWOOD TOURISM

Not only did Jack Benny and his radio cast talk incessantly about the movies—the geography of Hollywood and Southern California also suffused the program’s narrative. Early band leader Don Bestor plugged his orchestra’s performances at the Brown Derby restaurant, and Phil Harris was shameless in promoting his band’s shows at the Wilshire Bowl. Joking mentions of Pasadena, Glendale, the Rose Bowl, the May Company department store (where Mary had sold hosiery before she met Jack), Jack’s house in Beverly Hills, the NBC studios, orange groves, trips to Palm Springs, and (in the later 1940s radio shows) trains leaving Union Station for Anaheim, Azusa, and Cucamonga filled radio listeners’ imaginations with images and stories of both the real and an imagined Los Angeles.

California held alluring fascination for a great many Americans during the Great Depression. Tourist publications, WPA guidebooks, and annual winter articles in Eastern and Midwestern newspapers all encouraged vacationing in Southern California, touting sunny skies, warm weather, a variety of outdoor sports, festivals and parades, beaches, breathtaking scenery, and of course Hollywood.26 Tourism to the Los Angeles area grew rapidly in the 1930s, expanding from 200,000 to 1.6 million visitors between winter and summer, making it the region’s largest industry second only to petroleum production, and far ahead of motion pictures and the orange crop.27 Michele Hilmes notes radio’s ability to create a sense of nationality, Americanism, a leveling of social class, and gathering of immigrant cultures together to become a nationwide audience having a universal experience.28 The Benny show’s emphasis on Los Angeles played a role in creating an “imagined community” in Benedict Anderson’s phrase, to which all Americans could belong. In a 1940 New York Times interview, Benny explained how he used Los Angeles references strove to keep his radio program “typically American, not Broadway-ish”:

That is why I wouldn’t want to go on the air from New York for a whole season. We couldn’t be as rural or homey as we are in California. Out there we all feel that we are in a small town and can go places and do things as the people all do. It’s all right to come to New York for two or three weeks. But in the East we find ourselves acting like tourists. I’d never get a feeling for my Maxwell car or going to the country in New York.29

While visiting Hollywood ranked high among tourists’ goals, their expectations were nearly always crushed when they reached the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street, (then, as now, a pretty lackluster stretch of real estate), for there was little of the movie business that could actually be seen by the public. “The bitter truth, as most tourists learn, is that it is next to impossible to get inside a motion picture studio without knowing some on in the industry,” confessed one New York Times article. “Still it is possible to find plenty of Hollywood glamour outside the studios. The visitor may see his favorite screen star driving along Hollywood Boulevard, lunching at famous movie restaurants, playing polo or golf, or attending one of Southern California’ colorful motion picture previews.” The film studios were surrounded by high walls, big gates, and security guards. They didn’t hold tours, and it was nearly impossible to get in without a solid industry “connection.” “No industry receives more requests for permission to tour its factories and no industry, on the surface anyway, is more loath to accede,” warned another article.30 The movie stars were busy at work, and it was difficult to even get a glimpse of them at the Brown Derby, Ciro’s, or the Cocoanut Grove. Tourists had to be well informed and lucky to discover in which suburban theater a “sneak preview” of a new film was being held. The disappointed fan was stuck with studying a map of the movie star’s homes, or staring at the cemented celebrity footprints in the courtyard of Grauman’s Chinese Theater.

Into that celebrity-gawking vacuum came radio broadcasting. NBC and CBS opened studios in Hollywood in 1938. Sixteen of the highest-rated primetime network programs originated in Hollywood by 1939.31 While a greater percentage of a day’s overall programming was still produced in the East, the West ruled the night.32 The big radio shows were always anxious to attract audiences of tourists to provide laughter and applause. The studio auditoriums were not large (the one Benny used held only about 350 people), but tickets could be obtained at the studios, hotels, and the Chamber of Commerce ahead of time for free.33

The availability of radio performers to be seen by the public, in a town notorious for desire of its famous residents to avoid the masses, further boosted the association of Jack Benny with Hollywood. It was a newspaper-worthy event in the small upstate New York village of Ft. Plain in 1941, when an area man, John Galvin, who unexpectedly found himself mentioned on the Jell-O Program (Benny had stumped the visiting junior intellectuals, the Quiz Kids, with the question of who was the manager of the Penn Theater in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania). Galvin played Hollywood tourist himself and sent back a postcard, which his hometown newspaper editor gleefully published—“The former Fort Plainer sends a card—a picture of the Beverly Hills home of Jack Benny and Mary Livingstone, with the following note: ‘Dear Hugh, with Mary doing the dishes and Jack at the wheel of his favorite Maxwell. Rochester and myself did some FBI work hunting the gas man [whom Carmichael, Jack’s polar bear, was suspected of having eaten].’”34

Benny’s occasional broadcasts from the desert resort town of Palm Springs also added to the cachet of Southern California as a playground for the rich and leisured. Not only were the locals agog, but as the Benny show featured the town in the narrative of the program, it created valuable publicity to bring more Eastern tourists to see the sights Benny named. In 1941, the Palm Springs Desert Sun reported that “This village has never witnessed anything like the Benny broadcasts. Accustomed to celebrities of every kind and supposedly blasé, it went into a dither about Benny.”35 The newspaper estimated there were 3,000 requests for tickets for the two shows to be held at the local 750-seat theater, and a sales representative from General Foods had to rush in to help restore order. “[W]hile stores, newspapers, Chamber of Commerce, hotels and others are fully appreciative of the wonderful publicity and entertainment he is giving the town, they will breathe a collective sigh of relief when it’s all over.”

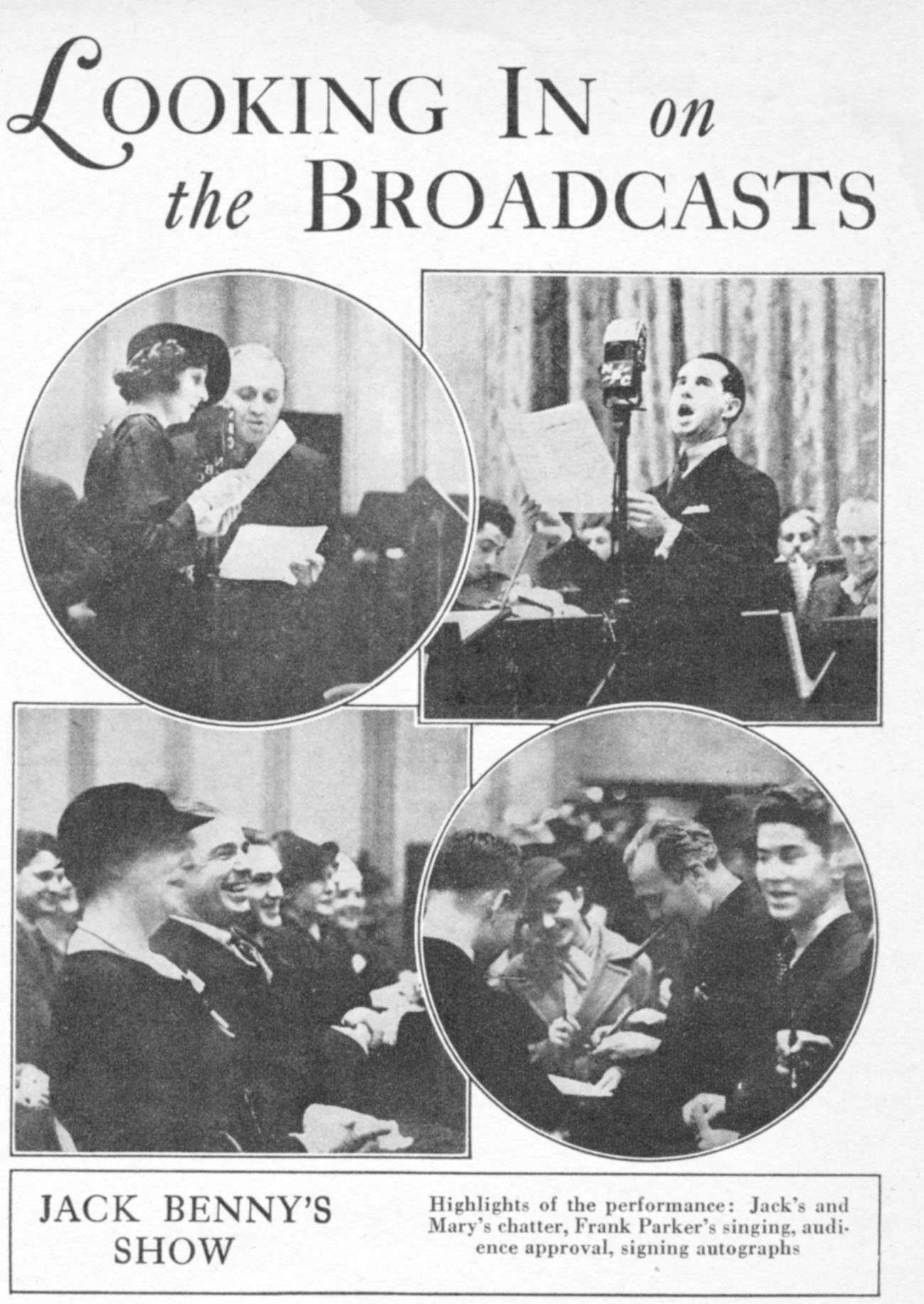

FIGURE 19. Fan magazines were anxious to give their readers the inside scoop on what a live broadcast of a popular radio show like Benny’s looked like, so they could imagine joining in with the studio audience. Radioland, March 1935, 8. Author’s collection.

THE CHALLENGES THAT RADIO’S SWING TO

CALIFORNIA BROUGHT TO THE MOVIES

By the time the broadcasting networks’ shows moved to Hollywood, in order to capitalize on film industry glamour, attract more movie stars to guest shots on their programs than they’d been able to do in New York, and to accommodate the intermedia activities of top stars, Jack Benny was already firmly situated in Southern California.36 Having the radio and film industries in the same city brought benefits and challenges. A concern for both broadcasters and film company executives dealing with the increased number of movie stars in guest appearances on radio shows was that some savvy stars and their talent agents were making these radio deals outside their contractual obligations to the movie studios. Film studio moguls were upset that movie stars were trading on their studio-created fame to benefit themselves. Stars might overexpose themselves, or (the studios claimed) injure their reputations by appearing on unsuitable programs. Movie companies sought to rein in their stars’ activities in this rival medium, while the movie actors and their agents fought for career autonomy and the welcome extra paychecks.37 Young and Rubicam executive Tom Harrington (Benny’s program manager) warned advertising agency radio departments in October 1936 that

radio has gone Hollywood, but it has gone Hollywood in a way that threatens its very future. We can’t help but feel that unless some action is taken we will find ourselves in the position of having crated a Frankenstein that will eventually be our undoing. Competition among the advertising agencies has become so strong with all the variety shows being broadcast from the coast as guest stars are at a premium and the scramble becomes a riot.

Rival advertising agencies searching for movie star power for their radio programs were bidding salaries for top stars up to unheard of heights of $5,000 per radio appearance.38 Radio industry people feared that radio would be reduced to just being a promotional outlet for motion pictures. New York Times radio reporter Orrin Dunlap warned that the film studios saw radio entirely as a promotional medium, not one of artistic creation, and that radio executives should worry that overdoing the publicity would make “radio suffer as an entertainment medium and the public will forsake such programs because of the ballyhoo.”39

This cross-pollination of media stardom caused consternation for both film studios and the nation’s movie theater owners, who had mixed reactions to what they termed “the radio question.” “Some exhibitors say an airing [of movie stars on radio shows] hurts show business, others that it helps. Some studios are fighting to restrain that broadcast impulse, or at least to secure compensation for star loan-outs, while others encourage it or at any rate look the other way when it boils over.”

Because radio could be listened to for free, film exhibitors and studio executives worried that having their movie stars exposed too abundantly on radio robbed them of potential revenue at the box office. Others saw promotional benefits from putting film stars on the airwaves, as the Paramount studio insisted that its contracted film performers give one free radio broadcast in connection with each film they made. Featuring radio stars in the movies might generate useful publicity for the film industry and draw otherwise reluctant ticket buyers to local theater box offices, but it might also represent a dangerous intrusion of the rival media form that would steal away paying customers from the movies.

Lurking beneath Hollywood filmdom’s façade of glamour in 1937 and 1938 laid a crisis that undoubtedly fueled the film studios’ jealousy of radio broadcasting’s invasion of its turf—the movies were in a severe economic slump, and studio moguls feared the industry might never recover.40 Catherine Jurca details the unhappy news faced by Hollywood film executives that too many new movies were lousy and that audiences were voting with their feet to stay away from theaters.41 Meanwhile, radio listenership continued to climb. Jurca points out that movie executives, on the offensive, began to search for what film audiences wanted, and if the answer was less glamour, more “natural” heroes and heroines, and more believable plot lines, then they developed and promoted “believable” stars like Myrna Loy and produced “family films” like the Andy Hardy series.

In February 1937, movie industry leader Will Hays held nearly seven hours of closed-door meetings with NBC West Coast executive Don Gilman and CBS executive Dick Thornburgh about “the motion picture artist situation,” to discuss the tensions between radio and film. Hays claimed that local film exhibitors across the nation were the ones angry about movie stars appearing on the rival medium (hitting them hardest at the box office). Gilman countered that NBC’s hands were tied—it was not in the networks’ control what programs the advertising agencies and movie stars’ managers put together; he claimed that “we can’t very well refuse programs which have been created outside of our control and which are acceptable as to the artists, material and product.” Gilman claimed that Hays understood that any actual loss of audience from theaters for free radio “is so minor that to be wholly unimportant,” but Hays reiterated that it didn’t matter what he thought, that it was local exhibitors who were upset. Hays diplomatically hoped that radio and film could work smoothly together as “cooperation . . . may cause them both to realize that broadcasting is a friend of the picture house.”42

Local radio broadcasters could be just as testy as local theater owners about film industry propaganda trying to persuade listeners not to stay at home. In October 1938, an angry radio station manager in Buffalo, New York, castigated NBC:

At the end of the “Good News” show from Hollywood last Thursday night October 20, the NBC announcer said “ . . . and remember, Movies are your best entertainment.” I wonder if this is sound policy for radio to be used to plug movies in this manner? . . . NBC policy prohibits boosting a BLUE [network] show on the RED, and vice versa, on the theory that it is unfair to one client on the RED to have his potential audience INVITED, and URGED, to tune in on a BLUE show running contemporarily on a competitive network. . . . Would it not be better for us to say “RADIO is your best and cheapest entertainment, and movies are your SECOND BEST”?43

NBC’s Royal sent this complaint to the Continuity Acceptance Department and asked its head, Janet MacRorie, to draft a response. Her internal memo, “Radio’s Contributions to the Motion Picture Industry,” was sent back up the line to executives up through NBC president Lenox Lohr.

Radio provides a ready-made audience for the motion picture theatre. . . . Many personalities, built up through radio, have become popular screen actors and big box office attractions for the motion picture producers. [She lists nineteen performers, starting with Jack Benny] . . . Review the expansion necessary in NBC properties alone at Hollywood and it will readily be seen that radio has to follow its own talent to Hollywood when radio personalities are found to be good box office for the movies. . . . If the motion picture industry contemplates any move to undermine the radio industry, it must indeed be blind to the benefits that is has accrued from this same source.44

“LET’S DON’T SNEER AT BENNY MUSICALS”: BENNY’S

RADIO-FLAVORED 1930S FILMS, AND THEIR INTERMEDIA

MARKETING

Jack Benny’s MGM film Broadway Melody of 1936 (1935) boosted dancer Eleanor Powell’s film career, if not Benny’s, and his subsequent feature, It’s in the Air (1935), was a mediocre film that, despite its title, concerned daredevil airplane pilots, not broadcasting.Frustrated at not being placed in better parts at MGM, Benny switched to Paramount, but found, however, that his roles did not appreciably improve. In Big Broadcast of 1937 (1936) and College Holiday (1936), Benny’s part continued to be that of a producer struggling to mount a talent showcase for college kids, crooners, or scantily clad chorus girls. Benny cracked some jokes, not very well timed, and exhibited lackluster chemistry with whichever leading lady or stooge he was paired with. His subsequent films for Paramount, Artists and Models (1937) and Artists and Models Abroad (1938), were again hamstrung by particularly weak narratives. These medium-budgeted, barely-better-than-B-level films drew little more than sniffs of disdain from film critics. The purpose of these movies, however, was to reach out to American movie audiences in the suburbs and hinterlands and offer them familiar and relatable characters. Pollster George Gallup’s surveys showed these audiences were bored with Hollywood’s overwrought dramas and brittle glamour-pusses. Benny’s mediocre films weren’t as weak at the box office, however, as some of the other dramatic and comedic bombs, which were contributing to the nationwide movie slump.45

As part of the film industry’s effort to reattract disaffected moviegoers in 1938 came a renewed effort by Hollywood studios to tap into radio performers’ popularity—radio singers such as Alice Faye, Dorothy Lamour, Kenny Baker [famous due to his role on the Benny program], Lanny Ross, Martha Raye, and Frances Langford were tapped for movie roles. Paramount hired popular radio storyteller “Arkansas Traveler” Bob Burns to appear in features (he made twelve by 1940). Rising young comic Bob Hope was chosen to appear in Paramount’s Big Broadcast of 1938, and Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, breakout stars on the radio in 1938, were given lead roles in two films at Universal, Letter of Introduction (1938) and Charlie McCarthy, Detective (1939).

Paramount lured away rising young director Mark Sandwich from rival RKO to help improve the quality of Benny’s films. The thirty-seven-year-old director had worked his way up from two-reel comedy gagman to innovator of the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musicals that interpolated music so ingratiatingly with the film plots. Sandrich’s first musical comedy breakthrough, a profile noted, had actually been “So This Is Harris [RKO 1933], a novel three-reel musical, starring a noted bandleader that startled the picture world with his unusual treatment of music. He made music MOVE—on the screen. He also incorporated the simple, but hitherto unused method of filming a musical in which the story . . . plot and situations . . . predominated.”46 Perhaps Sandrich’s fruitful experience with Phil Harris made him amenable to working with the bandleader’s radio boss.

Sandrich’s solution to the Benny problem was to focus on how to make Benny seem more comfortable on screen; the director oversaw the scripting, incorporating more of Benny’s radio-flavored dialog into standard filmic practices and utilizing other members of Benny’s radio cast. Sandrich and screenwriter Morrie Ryskind adapted a story Ryskind had co-written about an American show producer and his troupe stuck in London into a screenplay reminiscent of Benny’s radio comedy milieu. While Sandrich retained the story’s fictional narrative structure that gave Benny the film role of “Bob Temple,” Sandrich added radio cast members Phil Harris and Eddie Anderson, who in 1938 was quickly becoming popular as new cast member “Rochester” on the Jell-O Program. Sandrich structured the film like Benny’s radio program, incorporating established radio characters’ personalities and their typical bantering dialogue.47 But Sandrich also expanded the world of the radio show by significantly increasing Eddie Anderson’s part in the film, having him sing two big production numbers, and having him interact onscreen prominently with Benny. Sandrich’s efforts made Man About Town a surprise hit for Paramount, and incidentally, one of Hollywood’s earliest interracial buddy movies.

Benny’s broadcasting bosses General Foods, Young and Rubicam, and NBC brought an unprecedented intermedia marketing synergy to the world premiere of Man About Town, in late June 1939, investing time and a substantial amount of promotional funding to make it one of the splashiest publicity events of the year in either film or radio. Radio, advertising, and motion picture production corporations cooperated to mount a huge cross-media celebration of Jack, his radio show, and the new film in Benny’s hometown of Waukegan, Illinois. The gritty working-class town north of Chicago was inundated with an extraordinary five-day circus of media publicity events, with 300 journalists on hand to cover multiple parades, 150,000 spectators, several episodes of Benny’s Jell-O radio broadcast, dinners with town officials, downtown rallies with the stars, and simultaneous film premieres at the town’s three movie theaters. More than 2,300 extra policemen, national guardsmen, and boy scouts were brought in to Waukegan to help maintain order.

Paramount’s lavish promotional junket to Waukegan was part of a two-year film industry plan to increase business and brand awareness across the hinterlands by staging exploitation events in places far from Hollywood. Paramount had just held the world premiere of Union Pacific in Omaha. Warners (in Dodge City, Kansas, with Errol Flynn’s Dodge City), Fox (in San Francisco with Alexander Graham Bell and Joplin, Missouri, with Tyrone Power’s Jesse James), and MGM (in Atlanta with Gone with the Wind) participated in the outreach effort as well.48

Plans for the cross-media premiere-night spectacular, linking events onstage, on screen, and on the airwaves from Waukegan ran into a nearly disastrous last-minute snag, however, courtesy of the U.S. government. Variety reported, “When [the] Federal Communications Commission got wind of the airing in a theater where admission will be charged, it set down a heavy foot.” Radio producers were never allowed to require audiences to pay to attend a national radio broadcast. “Just about the time the Paramounters decided to split up the ceremonial; [General Foods] stepped in to announce it would buy out the house that night.”49 Jell-O pitched in to give away the combined movie-radio show tickets for free. Promoters estimated the premiere’s $125,000 price tag was shared between General Foods, Paramount, NBC, and Young and Rubicam.50

Paramount promised welcome relief to beleaguered local film exhibitors in their publicity releases for this film, crowing “It’s Your Year to Rake in the Jack” and “There’s Plenty of Jack in Paramount’s Man about Town.”51 Man About Town made a strong showing at the box office, earning 20 percent more than the average film during the summer slow season, when moviegoers usually stayed away from unairconditioned theaters and studios traditionally dumped mediocre films and light fare. Benny’s films were also released in the summer so as not to compete with his October-through-June radio show, and to capitalize on radio fans’ missing Benny while he was off the air.

Most reviews praised Sandrich’s efforts to blur the lines between radio and film entertainment, lauding Anderson’s performance as Rochester and noting how much more relaxed and natural Benny’s performance seemed compared to previous films.52 Variety complimented the screenplay, which they judged was “precisely tailored for Benny’s radio and screen personality.”53 Picture Reports claimed, “At last the screen captures the full flavor of Jack Benny’s distinctive radio character. Heretofore, the Benny pictures have missed the spark that has made the comedian the top ranking star of the airlines, season after season, but the man in Man About Town is the same boastful, blustering, likeable fall-guy millions tune in and laugh at every Sunday evening.”54 The Motion Picture Herald applauded Sandrich’s keen understanding of what made Benny radio shows work: “It has Benny in a jam and Benny the butt of the jokes and gags.”55 Box Office agreed, remarking, “It is the most advantageous screen vehicle yet concocted to parade the comedy talents of Waukegan’s gift to radio and films and, with its blend of mirthful story, situations, deftly timed gags and lavishly staged production numbers, should be reckoned a strong stimulant to ailing summer box offices.”56

On the other hand, Man About Town received only dismissive acknowledgements from the major New York or Los Angeles film critics, who disdained most of the radio-themed movies released by the film studios. “Let’s don’t sneer at Benny musicals,” reviewer Archer Winsten pleaded in the New York Post, praising the “good lines and comical situations” in the film that pleased audiences looking for simple pleasure.57

BUCK BENNY RIDES AGAIN—MERELY A FILMED

RADIO PROGRAM?

Signed to a long-term contract by a grateful Paramount studio, and promoted to producer/director, Sandrich proceeded to push the integration of radio and film even further in his second Jack Benny picture, Buck Benny Rides Again (1940). Sandrich hired Benny’s radio writers Ed Beloin and Bill Morrow to craft the dialog script, based very loosely on an expansion of the series of “Buck Benny” Western skits that had been performed on the radio show in 1936 and 1937. Sandrich incorporated even more members of Benny’s radio cast into the film, this time not only Harris and Anderson, but also announcer Don Wilson, tenor Dennis Day, and film actor Andy Devine who had played a continuing role on the radio program during the Buck Benny skits. Unlike in the previous film, the major performers in the film used their stage names and performed in their radio personas—Phil was overly attracted to the ladies, and Jack was penurious, vain, cowardly, and awkward around women.

Sandrich incorporated novel radio touches into the standard film context—Don Wilson read out the film’s title credits instead of them just being presented as text. Mary Livingstone and Fred Allen appeared, too, but only as voices emanating from onscreen radio sets (both performers were very reluctant to appear on film). Sandrich also made special efforts to make key imaginary aspects of the show visible on film. Carmichael the Bear and the Maxwell jalopy appear in the movie, to the delight of many film reviewers. Still there were limits to how much Sandrich was able to completely integrate these rival media forms—he had to cut out several lines Morrow and Beloin had written in which Jack and Mary (via radio) discuss the fact that the season of radio programs had concluded. Some intermedia lines were not crossed—there was no mention of Jell-O or radio commercialism in the film.

FIGURE 20. Jack Benny created invaluable intermedia marketing synergy by playing up the radio cast’s experiences on the set at Paramount producing their film Buck Benny Rides Again. It spelled both high broadcasting ratings and strong box office for this radio-themed film, set at a Western dude ranch. Movie Radio Guide, February 1940. Author’s collection.

The Benny program’s characters were integrated into a narrative that incorporated Benny’s typical radio-style insult-swapping into a standard Hollywood romantic comedy. Ellen Drew played Jack’s love interest as part of a sister singing trio seeking to break into radio. Their efforts to get Jack to help them kept misfiring, and Jack’s crush on Ellen was not reciprocated. The film cast traveled west to a dude ranch where comic mix-ups with cattle rustlers occurred, and pretty chorus girls danced and sang. Sandrich added a twist to the film plot that drew on a unique aspect of the Benny radio show, something not occurring elsewhere in mainstream Hollywood films, in that Eddie Anderson as the Rochester character again played a very substantial, co-starring role in the film as Jack’s sidekick. Anderson even got a romantic interest of his own, actress Teresa Harris, playing servant to the three singers.

Promotion of the film involved an impressive attempt at integration of separate entertainment media forms. On the radio, the Jell-O radio program’s fictional characters discussed their activities participating in the actual filming all during the movie’s production in December, and then throughout the spring building up to its premiere in April 1940. The radio characters’ dialogue dwelled on how much more popular Rochester had been on-screen than Jack in the previous summer’s Man About Town; it provided yet another new way to puncture Jack’s pretentions of being a successful movie star. Leading up to the premiere of Buck Benny Rides Again, the entire Jell-O radio cast journeyed across country to New York City for three weeks of broadcasts, plus guest appearances on other Young and Rubicam–managed radio programs. In an unusual and innovative intermedia promotional push, Paramount went to the extraordinary effort to stage not one but two world premieres of the film, one at the Paramount Theater in Manhattan, the other in Harlem at the Loew’s Victoria Theater.58 The gala interracial and intermedia event is discussed in the first Rochester chapter. Paramount’s Buck Benny press book presented ambitious language (if not followed through with more concrete promotional assistance from the studio for local theater owners) to demonstrate that a full intermedia publicity campaign could be possible for Buck Benny Rides Again—that radio, films and commercial sponsors could create synergies that would benefit local exhibitors:

Jell-O backs your showing with big co-op campaign! The distributors of the nation’s leading dessert—the sponsors of the nation’s number one air show, put their full power behind the cooperative selling of BBRA—launching a campaign to top their previous selling smashes on Jack Benny hits. Get out and get behind this enormous General Foods tie up, that links Jell-O merchandising and the drawing power of Jack Benny’s Sunday night air show, with your own box office on the new Benny show.

Paramount claimed that every episode of Benny’s radio program on the air, and every box of Jell-O on display at local groceries and chain stores, represented advertisements for this film. Meanwhile, the movie studio itself at least provided some brief phonograph recordings of music and dialogue and sample advertising scripts from which theater managers could craft local radio commercials. Paramount also arranged for cooperative advertisements in magazines and window card posters for product tie-ins with manufacturers of hosiery, overcoats, and typewriters, to help film exhibitors publicize their local screening of the film at cooperating neighborhood stores.59

Public opinion pollster George Gallup concluded in a 1940 survey of American moviegoers and moviegoing habits that Buck Benny Rides Again was the most effectively presold picture of the year (along with Paramount’s Crosby and Hope film, Road to Singapore), due to the “direct result of steady plugging on Jack Benny, Bob Hope and Bing Crosby [radio] programs.”60 Box Office Digest reported that Buck Benny Rides Again was a major hit, doing an impressive 34 percent better-than-average business in movie theaters in cities across the nation.61

Reviews of Buck Benny Rides Again in the film industry trade press and in newspapers around the nation debated the merits of the film’s radio influence.62 The Los Angeles Herald Express called Benny a “comic sensation,” claiming that “For the first time in Jack Benny’s amazing career in vaudeville, on the Broadway stage, on the air as American’s number one attraction and before Hollywood’s caustic cameras he has bounced forth with the identical charm, the ready wit and the belittling-of-self attitude that made him great in very other form of entertainment but the movies.”63 Box Office Digest said the film was “nearest to giving the comfortable ‘at home’ feeling to the spectator of spending a corking evening with a succession of Jack Benny air programs that has yet been achieved for an ether personality.”64 New York Mirror critic Kenneth McCaleb weighed the benefits and drawbacks of this intermingling of radio and film:

Radio audiences and motion picture audiences are, in theory, identical; each is supposedly made up of the great bulk of Americans who must watch the nickels closely and who seek escape and low-priced entertainment in these two media for the masses. The chief trouble with this theory is that it has not seemed to work out so well in practice. Cinematic moguls are still debating whether broadcasting by their stars, as part of radio’s standard soap and breakfast food operas, helps or hurts their film box-office standings. Personalities created or largely built up by radio have been borrowed in many cases by the movie makers, with uncertain results.65

McCaleb argued that Buck Benny Rides Again “is the first which completely transforms to film the radio character which he [Benny] has made for himself.” He thus predicted it would be the rare Hollywood movie to truly please radio fans.

On the other hand, the movie was savaged by the established film critics of the New York papers. The Herald Tribune’s Howard Barnes “deplored the sorry state of screen fare . . . which merely emphasizes the poor judgment which the screen is now displaying in forgetting fundamentals and playing to what used to be called the gallery.” B. R. Crisler, reviewing the film for the New York Times, waded through the crowds that snaked for blocks around the Paramount theater five abreast outside the box office and incredulously wondered what all the excitement was about. He found it a better than average Jack Benny comedy, but that

it is still more of a broadcast than a motion picture. There are some worthy people who are wedded to their radio, who like their entertainment handed to them in great gobs of dialogue interspersed with swelling crescendos of background music. And on the other hand, there are equally reputable persons who consider, fairly or not, that the screen is wasted on that type of picture. . . . Don’t blame us if Jack Benny in a cowboy suit hardly seems worth the trip.66

Declaring that, “If you can’t Abuse ’em, Use ’em, Hollywood makes Pix about Radio,” Variety discussed film studios’ efforts to dive more thoroughly than ever before into radio-themed movies:

The motion picture industry has ceased to abuse radio and is using it as a background for a score of films, and more to come. Practically every major studio is producing or preparing features dealing wholly or in part with broadcasting. Some of them are built entirely around the microphone, and there is no answering kickback from the exhibitors, who used to protest against the inroads of the ether programs on the film business. Paramount leads the studios in the use of radio backgrounds for the screen, with six features of that nature completed, in production or in preparation. . . . Throughout the celluloid industry the broadcasting background is a growing rival of the canyons and prairies.67

A year-end round up in Variety described the added urgency studios felt to discover what the American moviegoing public would pay for, now that the foreign markets, which had brought in about 40 percent of revenues, were seriously curtailed by wartime disruptions.

Gallup’s research reports on the habits of American film audiences confirmed that an increasing number of Americans spent more time listening to the radio than attending a movie show. “While 11,500,000 cinemaddicts sit in their favorite cinemansions of an average Sunday, 34,000,000 radio fans listen to Jack Benny on the air. On an average Monday 5,428,000 go to the movies; 26,000,000 stay at home to hear the Lux Radio Theatre program,” Gallup noted.68 Radio was competition that needed to be co-opted, if Hollywood was going to hang on to any audiences in these unsettled, perilous times.

Jack Benny became one of Paramount’s top three male movie stars at the box office in 1939 and 1940, and among the top twelve stars industry-wide through 1942.69 If the public would only come out to theaters to see highly promoted but mediocre films starring radio performers, then Paramount would produce them. Nevertheless, using radio celebrities who broadcast only in the United States made these films questionable for the overseas movie theaters they could still reach. The Times of London would consider Sandrich’s subsequent Benny effort Love Thy Neighbor a poor and forgettable a film, noting that London movie audiences had never heard of Fred Allen, and “the frequent allusions to the Benny-Allen feud will doubtless remain a sealed book to Britishers.”70

LOVE THY NEIGHBOR AND THE LIMITS OF

INTERMEDIA FILM MARKETING

Mark Sandrich attempted to translate the Benny-Allen feud to the screen into a buddy-rivalry film to match the smash box office success of Paramount’s other radio-star-flavored success released in spring 1940, Bing Crosby and Bob Hope in The Road to Singapore.71 Love Thy Neighbor, however, was a weak and weary film. Sandrich had to beg Fred Allen to participate, as Allen despised both films and being in Hollywood, and it seems obvious from his unenthusiastic performance that Allen’s heart was not in the film. Eddie Anderson, the runaway star of both Man about Town and Buck Benny Rides Again, found his role as Rochester significantly reduced in this film, as he was relegated to third wheel status.

The comic potential of the film was frittered away. Paramount tried to add extra spice to the movie by featuring young Broadway actress Mary Martin, who had made a huge hit in New York performing a scandalous strip tease while singing Cole Porter’s comic song “My Heart Belongs to Daddy” in the 1938 musical Leave it to Me! The Hays Office made sure to sanitize the song’s lyrics and any suggestive dancing before Martin could perform the number on film, however. Further, Martin had no more chemistry in a romantic subplot with Jack Benny than any of his other leading ladies had ever aroused. The movie’s jokes weren’t particularly funny and the slapstick scenes seemed forced.

Love Thy Neighbor was released in late December 1940, a prime time for Hollywood’s family films and box office hits. Although the premiere at the Paramount Theatre in New York was smaller in scale than Benny’s previous films, his and Allen’s radio programs were at the top of the ratings, and the film earned the largest gross of any film during the holiday week, doing 144 percent of standard business. It was Paramount’s second biggest release of the year, surpassed only by Cecil B. DeMille’s Northwest Mounted Police.72

Despite success at the box office, Paramount’s promotion of this film gives the impression that the studio was rapidly losing interest in Benny. Radio sponsor General Foods and ad agency Young and Rubicam’s efforts similarly also seemed lackluster, in comparison with their previous exertions. Jack Benny undoubtedly noticed this too, for in the aftermath of the film’s release, he signed an unusual contract to simultaneously make films at two other studios, Warner Bros. and 20th Century Fox. He also contemplated shopping his radio show to other sponsors. While the press book for Paramount’s advertising campaign for Love Thy Neighbor claimed “What is far and away the greatest radio campaign ever put behind a motion picture is going on right now,” all the studio offered was the appearances of the film’s stars on their regular radio programs, and several guest appearances made by the performers on each other’s shows to promote the film. Paramount grandly suggested that local film exhibitors could corral all the grocers and Texaco gas station managers in their neighborhood together to support a city-wide celebration of Jack Benny and Fred Allen. Or to display a pile of Jell-O boxes in their theater lobbies. Perhaps most heretical to the minds of local movie theater owners jealous of having their audiences stolen by home radio sets, the press book suggested that exhibitors “rig up a radio in your lobby and have it go on when any of these programs [featuring the film’s stars] is on. You can rest assured that there will be something in each of the programs which will help you sell Love Thy Neighbor. Do this now!”73

Variety characterized Love Thy Neighbor as “hardly a picture for the critics,”74 but New York’s top-ranked film reviewers utterly despised the film, panning its surfeit of dialogue and paucity of plot. New York Times reviewer Bosley Crowther grumbled that its meager narrative, interrupted by crescendos of music and slapstick, was merely “the tired jibes of a four year old, fake feud.”75 Crowther bemoaned the scourge of radio-themed films in an essay that was supposed to have been an end-of-year discussion of Hollywood’s best productions.76 “From the way some people talk in the motion picture industry you’d think that the radio was a great big measles sign hung on the industry’s door, keeping patrons away from movie theatre in alarming wholesale numbers.” The rivals had nevertheless been exchanging performers, plots, and formats for nearly ten years, he fretted. He railed at recent films that abandoned “cinematic potentialities” and created merely “as close a reproduction of the air thing as is technically practical.” The critic warned that film producers’ cynical efforts to make money at the box office were “most deplorable and dangerous, for it fails to regard above all the essential nature of the film medium. It presumes that a picture is merely a show window in which to display a radio attraction, not an artistic entity with definite demands for perfection.” Crowther condemned Love Thy Neighbor for failing to engage the artistic potential of film:

Once or twice there are glimmers of some real cinematic inventiveness, such as a speedboat chase sequence in which the boats, making turns, are accompanied by the sound of screeching brakes and sliding tires, and a bit in which Rochester converses with his reflected conscience. But insistently the picture snaps back to the old routine of Mr. Benny and Mr. Allen flaying one another with words. . . . If the industry seriously suspects the radio of alienating its public, then this seems like a very queer way of meeting the competition—unless, of course, it is really intended as a subtle form of sabotage.77

The aesthetic deficiencies that Crowther and the other disapproving critics point to in Love Thy Neighbor and Benny’s other radio films would parallel complaints about lack of visual interest and physical action that television critics would toss at the radio programs and performers that attempted to transition from the ether to the visual medium in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

• • •

While Love Thy Neighbor earned handsome profits for Paramount in early 1940, the studio did not produce the subsequent films for which they had contracted Benny and Anderson. Mark Sandrich turned to serious dramas, and Paramount instead turned to Bob Hope and Bing Crosby to create future radio-inflected comedies. Benny and Anderson appeared separately in successful films for other studios in the early wartime years; they were also paired again in a 20th Century Fox studio adaptation of a George M. Cohan stage comedy, The Meanest Man in the World (1943). Major scripting problems resulted in a very mediocre film. By 1946, both Benny and Anderson had appeared in their final major Hollywood movie roles.

The intermedia blending of broadcasting and film in Jack Benny’s radio program was extraordinarily successful. Despite the numerous constraints put in place by the rival media companies, sponsors, and local film exhibitors, Benny and his writers had managed to negotiate a path that enabled them to playfully incorporate jokes about both entertainment forms. Benny used his self-deprecating comments about his own Hollywood career to pull back the curtains of movie star glamour. And yet the disdainful cinema stars who showed nothing but contempt for Jack reinforced the mystery of their superiority. The Benny program’s innovative parodies of current Hollywood hits helped to dispel the pretensions of sophisticated melodramas like Grand Hotel or The Barretts of Wimpole Street or The Women, while also spreading the fame of those films further into popular culture.

Hollywood stars and movie references became more incorporated than ever into Jack Benny’s radio program during its “golden era” of renewed popularity and humorous achievement from 1946 to the early 1950s. The arch disdain of movie star Ronald Colman for his next door neighbor was a superb addition to the radio show’s comedy, and created a rich vein of humor that highlighted the difference between Hollywood social class and Benny’s Fall Guy failings. The program’s reputation among Hollywood celebrities of treating guest stars with kid gloves, making them sound intelligent and funny, won for Benny the appearances of many top actors and actresses (such as Claudette Colbert and Humphrey Bogart) who would not deign to be on other comics’ programs. But the Hollywood industries, film and radio, would face disruptive competition from New York City–based television, beginning in 1948. The last two chapters of this story about Jack Benny’s radio career will examine how he faced the two greatest challenges of his radio career—addressing the wartime creative slump into which his program fell and how he and his production team innovated comedic elements to create that “golden era” of the radio show, 1946–1952. And then how, once back on top of the radio ratings, Benny nervously approached the transition to television.