Looking back over his twenty-three-year career in radio broadcasting, Jack Benny had so much of which to be proud. He had become one of the most familiar voices on the radio, America’s first truly mass medium of communication, speaking weekly to thirty million or more listeners. In the preceding chapters, we have explored how brilliantly Benny moved between separate entertainment forms, combining aspects of vaudeville and film, radio and live performance. Benny created new styles of entertainment as he honed his career, from developing the master of ceremonies role—the modern, urban, polished, but self-deprecating figure who informally drew audiences and disparate acts together into a whole—to the lead character in a situation comedy—that new episodic form demanded by the needs of radio broadcasting’s massive time demands and broad reach. Benny and his writer Harry Conn developed the iconic character of “Jack,” the “Fall Guy,” vain braggart, frustrated employer, disrespected media celebrity, the butt of every joke and insult slung by his workers.

Benny and his writers over the years not only created his own famous character, but in developing the sitcom they also honed a cast of delightful characters who melded crazy fictional characteristics with excellent performing skills of talented players—Mary Livingstone, and Eddie Anderson’s Rochester Van Jones in particular. The Benny show humor frequently used these main characters to parody and impertinently tweak social norms of midcentury American society—that women should be quiet and obedient; that middle-class white men should be strong, virile leaders; that African Americans should never critique their employers. Benny and his production group developed a particularly effective form of aural humor, where the laughs came not from old jokes refreshed with new surroundings, but the humor of character, of sounds like the Maxwell, of silences such as Jack’s exasperated humiliation, of surprises like Mary’s sudden retorts. The Benny group managed even to make the often-dreaded commercial language sound hilarious. American audiences loyally listened to him, Sunday nights at 7 P.M., whether they were eating dinner, sitting around their sets, or driving in their cars. The Benny program was as familiar as family, even as its humor slyly questioned ideas about how relationships, power, and identity should work in modern society. Jack Benny was, and remained, an American institution.

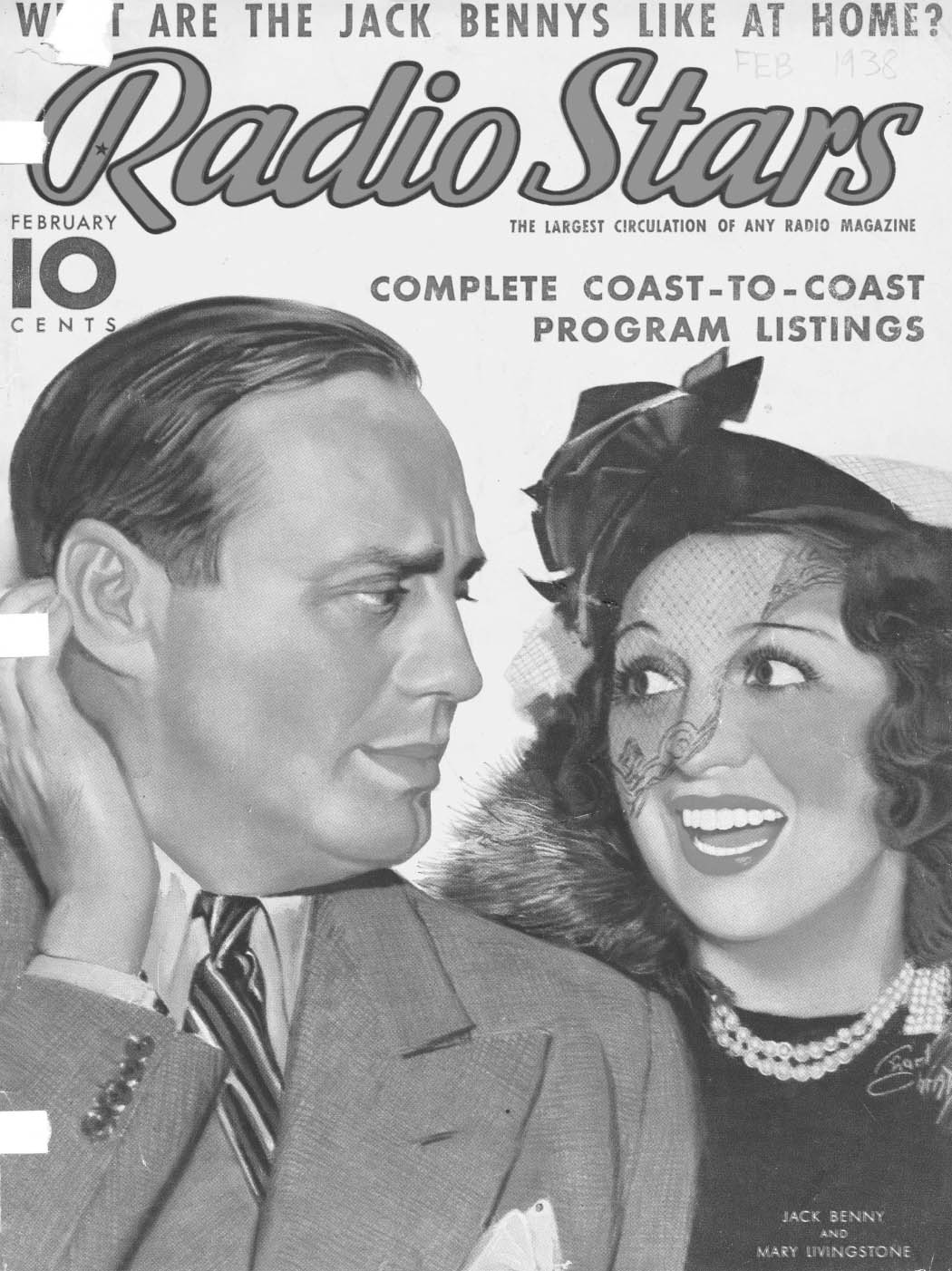

FIGURE 26. The biggest star in radio, when radio was the most prominent mass medium in the United States. Radio Stars, February, 1938. Author’s collection.

He may have concluded his radio career in May 1955, but, far from retiring, sixty-one-year-old Jack Benny remained as active a performer as ever—appearing regularly on television, in live stand-up comedy shows, and in charity symphonic musical performances. The narrative and comic ideas of Benny’s radio show remained at the core of his character and star persona, seamlessly woven into his humorous monologues and long lasting in the public memory.

Benny created and starred in his own half hour television program for fifteen years, from the broad variety programs of the first “golden age” of live broadcasting in the early 1950s, through the predominance of produced-on-tape sitcoms in the networks’ weekly schedules in the mid-1960s. Benny’s TV show often featured sketches directly adapted from the old radio show, and incorporated long-running radio characters Don Wilson, Eddie Anderson/Rochester, the Sportsmen Quartet, and Mel Blanc in his many guises, as well as the wheezing Maxwell and the underground vault. As they had in radio, the characters did not need to appear every week to remain a vital part of the Benny narrative—they were so well established in the audiences’ minds that they could pop up every once in a while, so the occasional appearance of Frank Nelson’s obnoxious sales clerk, Mary Livingstone, Dennis Day, the Beverly Hills Beavers scouting troupe, or put-upon Hollywood celebrities like Jimmy Stewart did not require elaborate introductions. Benny and his writers still took care, as they had always done, to keep changing up the mixture, adding new skits, occasional new characters (like Harlow, Don Wilson’s son, the apprentice announcer), and special guests, to keep the show fresh and not completely tied to a situation comedy format.

Between 1954 and 1958, Jack Benny also regularly appeared on the CBS monthly Shower of Stars variety program, serving as emcee or doing a one-off comic or dramatic skit that amplified the narrative world of his regular show, or that reinforced Benny’s larger star persona (as his film roles had done in the 1930s and 1940s). In a February 13, 1958, episode of Shower of Stars, “Jack Benny Celebrates His 40th Birthday,” the show reunited notable performers from the comic’s radio days, including early announcers Paul Douglas and George Hicks from 1932; orchestra leaders George Olsen, Don Bestor, Ted Weems, and Johnny Green from 1933; and even pinch-hitting tenor Larry Stevens from 1944. That Benny assumed members of the TV audience fondly remembered the unseen cast-mates from more than twenty-five years before is a testament to the long-lasting relationship he had with his fans. Benny and his radio cast also voiced an adorable Warner Bros. Looney Tunes cartoon produced for exhibition in movie theaters, which was based on his radio show, “The Mouse that Jack Built” (1959). As Mel Blanc was the most prolific and popular vocal artist in the Warner Bros. studio animation department, the short made for a perfect combination of nostalgic fun and transmedia adaptation of Benny’s narrative world.

While incorporating references to his old radio world into many of his projects, Jack Benny’s later career also continued to touch on the developments Benny had brought to American entertainment. Benny appeared in televised situation comedies, the episodic character-focused comic form that Benny’s radio program had done so much to develop, back in 1932. Benny appeared occasionally, usually as “himself” and not a completely fictional character, in Danny Thomas’s Make Room for Daddy, and Lucille Ball’s The Lucy Show. Lucy had wanted to have Jack guest star on her program while creating I Love Lucy in the early 1950s, but at the time her recalcitrant sponsor, Philip Morris cigarettes, forbid a performer associated with another tobacco brand to appear on its program.1

In the 1950s and 1960s, Jack Benny became a popular attraction at the Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe casino resorts. He developed solo stand-up comedy routines, expanding the work he had done back in vaudeville, on the road in USO tours during World War II, and in the earliest of his TV shows. Adult-focused, sophisticated, nightclub stand-up performers really came into their own in the 1960s,2 and Benny added some frank language to his basic Fall Guy routine, and did well in tours of British venues and a one-man show at the Ziegfeld Theater on Broadway in 1963. Benny took this solo routine as well to television, from guest shots on the Ed Sullivan show to cameo appearances on the hip programs aimed at younger primetime viewers such as The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour and Laugh In, and in the Dean Martin celebrity roasts in the early 1970s.

Jack Benny made guest appearances on late night talk shows, a new television program form that had its roots in Benny’s performance style. In fact, legendary talk show host Johnny Carson was a fervent Jack Benny fan and considered Benny a role model and mentor. As an undergraduate student at the University of Nebraska in the late 1940s, Carson was greatly influenced by the work of top radio comics, particularly Benny and Fred Allen. He wrote a smart and witty senior thesis, “How to Write Comedy for Radio,” and submitted it in recorded form, which can be accessed online through the University of Nebraska’s website.3 Since Benny’s vaudeville work in the 1920s as an emcee had an informal ease that connected him to the audience, him to the acts, and the self-contained acts to the audience, his performances were a prefiguring of talk shows he appeared on, such as Carson’s and Dick Cavett’s.

In this era, Benny also rediscovered his passion for the violin. He practiced at home four hours a day, his daughter Joan recalled.4 He donated a tremendous amount of time and energy to give charity concerts to raise funds for struggling symphony orchestras around the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. Benny would state wistfully that he knew audiences flocked to the concerts to hear Jack massacre sonatas in comic fashion, but he longed to play as a serious musician.

Benny remained a potent symbol for promoting consumer goods, and in the 1960s he was active in commercial product advertising, pitching Texaco gasoline, insurance, television sets, and other products. Not only did Jack Benny always carry with him listener memories of the old radio show, but also audiences persistently associated him with Jell-O and Lucky Strikes. Advertising executives marveled at the longevity of that link and wished they could manufacture that alchemy of long-lasting positive identification. One remarked in 1962 that “Still, no performer today . . . is as associated with a product. Maybe that is good, maybe it’s a very rare combination to make something sugary or something deadly, so much fun.”5

The rapid series of wrenching cultural changes in the 1960s made all the old established comedians seem behind the times, and out of touch with the hip culture of the younger generation. Benny fared better than some of the more purely nostalgic entertainers like Eddie Cantor and Bing Crosby, who seemed so wedded to their old musical choices. Benny continued to play “himself,” the Jack character who was vain about his age, frustrated by the impertinence all around him. He didn’t require the radio cast’s presence and insults to enact who he was, and in doing solo bits, in my opinion, he was often funnier than on his TV show. It helped that Benny did not tell standard jokes as did Henny Youngman or Milton Berle, and that he kept his humor to cultural foibles as experienced through his own persona—if he had done political jokes like Bob Hope, the younger generation would have rejected him. Benny’s best friend George Burns also aged well, reinventing himself as an ancient commentator. Despite his advancing age, Jack always managed to sound like he was in the present, instead of being merely an oldie-goldie act. Part of that genius is that Jack’s cheap, Fall Guy character could continue to react to any new situation.

After his regular TV program was cancelled in 1965, Benny continued to front at least one Jack Benny special per year for NBC between 1966 and 1974. In one of them, Jack Benny’s Bag (NBC, November 16, 1968), he and Phyllis Diller performed a wicked parody of the hotel room seduction scene from the recent film The Graduate, the box office hit beloved of the younger generation. Benny in a black wig played young Benjamin Braddock being pursued by sex-hungry Mrs. Robinson (you have just got to watch this, hopefully it is on YouTube). Benny merges his classic character with a spot-on comment on the film, with a memorable sex-joke charm. (The accompanying renditions of the film’s Simon and Garfunkel songs by young soul singer Lou Rawls and has-been Eddie Fisher adds to the bizarreness of the sketch.)

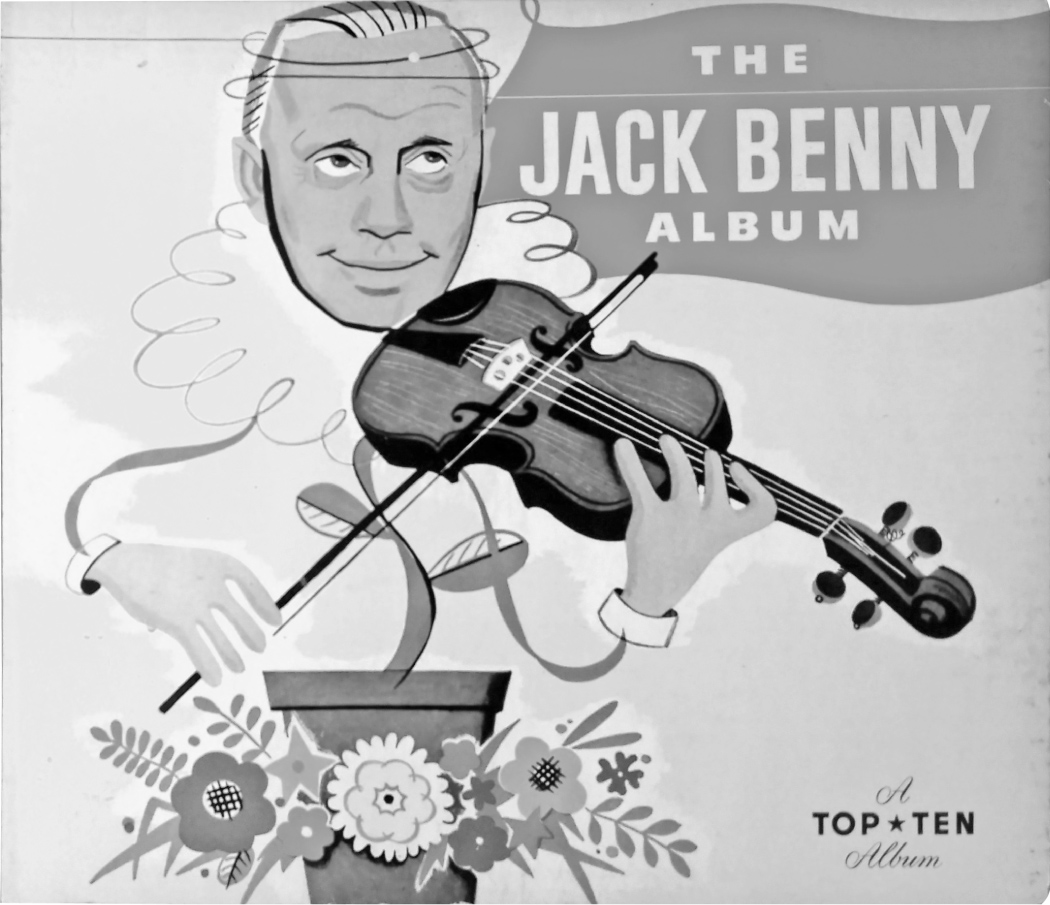

FIGURE 27. Jack Benny attempted to build the market for fans to purchase recordings of his best radio comedy routines so that they could collect and savor examples of his humor when was not broadcasting live on air. The Jack Benny Album, 1947. Author’s collection.

• • •

This is where I came in, as that twelve-year-old who wanted to learn more about Jack Benny’s radio programs. Originally broadcast live, out into the ether, they had become orphaned entertainment, unsaved, ephemeral, and gone. How foolhardy of sponsors, radio networks, and performers, to consider all this material as useless as last week’s newspaper. The fact that we have any historical broadcasts to listen to today is due to the efforts of hundreds of individual Jack Benny fans.

Jack Benny himself had attempted in 1947 to extend the ephemeral life of his live radio broadcasts by recording some of his best routines. Prominent radio performers had recorded a small collection of albums, the Top Ten series distributed by the Monitor label, which also included recordings of Amos ’n’ Andy, Bergen and McCarthy, Burns and Allen, Cantor, Duffy’s Tavern, and Fibber McGee. The series was, unfortunately, a commercial failure for the artists. Perhaps the series was not marketed well, as the records weren’t released with the full promotional heft of CBS’s Columbia records behind them. Perhaps radio audiences had not yet been educated to desire to collect and savor a library of comedy recordings. The market for comedy recordings did begin to flower in the United States in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Perhaps Benny was too far ahead of his time.

While in retrospect it seems foolish and wasteful for radio networks and sponsors not to have produced recordings of radio entertainment broadcasts, as broadcasting historian Eleanor Patterson notes, many factors militated against it. The ethos of network radio was liveness, and they discouraged the playing of records on the radio (musicians’ unions supported these measures too, to keep workers employed). The quality of audio recording technology was very mediocre, prior to the development of magnetic tape recording processes in the post–World War II years. The material was considered topical and not worth archiving, and also tainted with its thorough commercialism. Network television continued these practices through the mid-1950s, as Derek Kompere documents.6 Nevertheless, plenty of radio transcription disks were produced for sponsors and performers to keep records of their programs, and syndicated programs like “The Lone Ranger” were distributed to stations across the nation in recorded form.7 Transcription disks, made of 16-inch thin platters of aluminum (glass during the war) reproduced broadcasts well, but were fragile to store, and could be replayed only a limited number of times. Network demands for liveness would only begin to change with the success of TV programs like I Love Lucy being produced on film and becoming available to fill the many extra hours of airtime as reruns, as Kompare describes.

In the 1960s and 1970s, fans of what was beginning to be called “Old Time Radio” (OTR) found ways to locate transcription disks, unearthing them from garbage dumpsters, and rescuing them from dusty old warehouses. They made sound tape recordings of the disks, many of which were very scratched, damaged, and incomplete. Other broadcasts were culled from the recordings made by the Armed Forces Radio Service that had been sent to military bases overseas (these shows usually had had the commercials removed, further chopping up the original programs). OTR fans started to trade tapes with other fans, and began to build collections. Jack Benny had stored his old transcription disks in a hot Los Angeles storage unit, and those that he donated to UCLA when he gave them his collection of business papers, in the 1960s, were in bad shape, many so disintegrated that they were unplayable. Several entrepreneurial third party organizations commercially repackaged old radio programs for nostalgic enjoyment and sold sets of records and tapes.8 Through fifty years of dedicated collecting, OTR devotees have amassed about 750 full or partial recordings of Benny’s radio episodes. With digitized recordings, today we listeners can gain an appreciation for how past audiences, partaking of the Benny show in thirty-minute episodes aired weekly over many years, were rewarded with a long familiarity with the recurring characters, situations, repeated gags, and inside jokes that Benny and his writers wove into their episodes and could reference from years past. The website that I have created to accompany this book (www.jackbennyradio.com) also features material that audiences have not been able to hear since they were first broadcast in 1932 to 1936—excerpts from the scripts of Jack Benny’s live programs for which no recordings survive. There are more than 250 episodes, and hopefully some contemporarily recorded re-creations of some of the best skits, will help bring new audiences, and critical appreciation, for the superb comedic work Benny and Harry Conn created in the first four years of the program.

FIGURE 28. The “Top Ten” series of record album releases were early, unsuccessful attempts to provide consumers with permanent copies of emphemeral live broadcasts. In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, dedicated fans of “Old Time Radio” would collect, tape, organize and share the large collection of Jack Benny radio show broadcast recordings that we have available today. The Jack Benny Album, 1947. Author’s collection.

A number of comedians from the 1950s onward have claimed Benny had a formative influence on them, from Carol Burnett and Bob Newhart to David Letterman, Phil Hartman, Kelsey Grammer, Harry Shearer (who played a Beverly Hills Beaver, back in the day), Albert Brooks, and Kevin Spacey. Hopefully Benny’s legacy will continue, and the continued circulation of his radio programs as classics of American humor might be the way to do it. Ultimately, Jack Benny’s accomplishments in radio and lasting legacy in American humor and cultural history are tremendous and long lasting, and hopefully will impact future generations.