THE HOLLIES WEREN’T SATISFIED WITH NURSING OUR homegrown success. To make it—to have a long-lasting impact on rock ’n’ roll—you had to crack the American market. That’s where it all started, where Elvis and Buddy and Chuck and Fats and Ray and Richard and Phil and Don were. It’s where Leiber and Stoller ran the factories, where Phil Spector built walls of sound and Berry Gordy cranked out hits on the Motown assembly line. Music history was being written in every major American city—by Allen Toussaint and Ernie K-Doe in New Orleans, Sam Phillips in Memphis, the Chess brothers in Chicago, the Ertegun brothers and Florence Greenberg in New York, Alan Freed in Cleveland, Dick Clark in Philadelphia, in Nashville, Los Angeles, Lubbock, even Hibbing, Minnesota. America was the holy land for any English band, and we were determined to pray at the altar.

It wasn’t going to be that easy. Cliff Richard and the Shadows had gone there in 1962 and were treated like riffraff. No one took them seriously. Even the Beatles had been given the cold shoulder by three different record companies before they got a break. But once again, they had cracked open that door, and we intended to squeeze through after them.

Trouble is, we didn’t have a huge hit out in the States. We didn’t have a hit of any kind. The only record of ours that was released there was “I’m Alive,” which failed to crack Billboard’s Hot 100. So we still didn’t have an offer to perform there.

In April 1965, we finally got our chance. A guy named Morris Levy asked us to be part of a show he was producing at the Paramount Theater, in Times Square in New York City. Now, at the time, we didn’t know Morris was one of the music industry’s heaviest hitters, which was no exaggeration on several fronts. But he said the magic words “New York,” and we sure knew the Paramount. It’s where Frank Sinatra had played—and Buddy Holly. Where Love Me Tender had its premiere. It was Mecca, a very big deal. Don’t forget, the Hollies were still basically Manchester boys; being in the Smoke was a big deal for us. Just to play for American rock ’n’ roll audiences was enough of an incentive to make us salivate.

I couldn’t wait to get over there. I was packed and ready to go weeks in advance. Except, as it turned out, international travel was outside of our expertise. We got to Heathrow, ready to roll, only to discover our visas weren’t in order. You had to prove to American authorities that only you could do the job you were being hired for before they let you into the country. Somehow our handlers had overlooked that proviso. So we checked in to the Aerial Hotel at the airport, where we would be quarantined while they sorted it out.

Getting those visas stamped went right down to the wire. The Paramount gig was in five days’ time, and after four days being cooped up in that airless room I was getting a little nuts, to say the least. Finally, with no time to spare, the visas came through and we took off for New York.

No need to tell you it was worth the wait. America was everything it was cracked up to be—and more. We arrived fairly quietly, not like the Beatles, no press corps waiting, no entourage. We took care of ourselves, carried our own luggage. When we landed, we got shoveled into the most enormous taxi I’d ever seen; it had like three doors on each side. The driver kept turning the radio dial and there were hundreds of stations, all playing rock ’n’ roll, news, R&B, pop, classical, whatever you wanted. You could find it in an instant. We were used to the BBC’s despotic monopoly of the airwaves, listening to whatever they wanted us to hear. Choice was never a factor. “You don’t like Rosemary Clooney, too fucking bad. That’s what we’re playing at the moment.” Not in New York. Spin the dial, you got the Ronettes, the Four Seasons, Gene Pitney, Sam Cooke, Dion, Nat King Cole, the Impressions, Jackie Wilson, the Beatles … It was a musical banquet, and we gorged ourselves on it all the way into the city.

We barely had time to check in to the hotel before soundcheck, but my head was spinning from the glitzy cityscape. Walking along Broadway gave me the chills. It was just like in the movies. The lights and the people were insane. I couldn’t take my eyes off the Camel billboard that blew gigantic smoke rings into the air. And right across from it, just north of Times Square: the Paramount, in all its gaudy glory. This wasn’t some shithole in Hoboken. It was the big time, and cavernous: 3,500 seats, with marble columns, a crystal chandelier like they had on the Titanic, a grand staircase, and balconies layered one on top of the other like a New York skyscraper. I immediately climbed to the top of the theater, the very last seat in the last row of the house, and stared down at that empty stage, contemplating who had played on it and how I had gotten there. I thought: If only my parents could see where I was sitting. They’d never even made it to London, and here I was, about to play the Paramount in New York.

The gig was the Soupy Sales 1965 Easter Show, with one of those Caravan of Stars–type lineups—the Hollies and eleven other groups. Half of the acts were less than forgettable, just schlock tacked on to pad the bill. But there was enough starpower to keep us interested: Shirley Ellis, Dee Dee Warwick, the Exciters, and King Curtis and the Kingpins. Bobby Elliott, a stone-cold jazz fan, was thrilled to meet Ray Lucas, who was King Curtis’s drummer. But for me the payoff was playing opposite the headliner, Little Richard. That fucker was one of the greats, up there in the pantheon. I’d cut my teeth on “Long Tall Sally” and “Lucille” and “Good Golly, Miss Molly.” They were twenty-four-carat rock ’n’ roll hits. Fifty years later, I still get off on them. Richard hadn’t had a hit in seven or eight years, but no one gave a shit; he and his band still brought down the house.

The Hollies were ready to show America our stuff. I remember telling the stage manager, Bob Levine, “Our show is about forty-five minutes,” and he went, “Yeah, well, that’s not happening.” What? “You’re gonna do two songs.” What? “That’s right, two songs—for five shows a day.” What? “That’s the long and short of it, baby.” They packed those screaming teenagers in there, trotted us out like beauty-pageant contestants, then right out the revolving door again—five times a day. The first show was at 10:30 in the morning. Try getting it up at that time of day. We played “Stay” and “Mickey’s Monkey” over and over and over and over. And we didn’t finish until nine at night, so when we walked out of the Paramount onto the street, Times Square was lit up like a Roman candle. We’d be rubbing our eyes just to get ’em to focus. What?

Even with all that, doing the show wasn’t a grind. We were thrilled to be there, especially watching the master, Little Richard, five times a day. The guy was unreal. An incredible showman. He’d pound that piano as if it were a tough piece of meat and throw his head back and wail. And that band of his kicked ass, especially his guitar player, a young, skinny kid with fingers out to there. One night I was standing in the wings as Richard came off the stage and he was livid, his eyes bugging out like a madman, screaming like a motherfucker at that poor kid. “Don’t you ever do that again! Don’t you ever upstage Little Richard!” They got in the elevator, slammed the gate, and I could still hear him ten floors above, taking this kid’s head off. “You hear me, motherfucker! Fuck you—playing your guitar with your teeth!” He was called Jimmy James then, but you don’t need me to tell you it was Jimi Hendrix. Probably the only guy who could steal the spotlight from Richard.

New York, New York. I was in love with the place, and it kicked off my lifelong romance with the States. Every night, after the last show, the guys and I would head out onto the street, not knowing what to expect out there. It was a different town in those days, still something of an asphalt jungle. None of us ever went anywhere on our own. The Hollies stuck together out of camaraderie—and for protection. If anything were going to happen, you’d have to fuck with the five of us. The first day I got to New York, I’d opened the newspapers and there were like eight fresh murders on the front page. I remember reading about one guy who had been killed for a fucking quarter! So we were pretty cautious out there on our own. Walked all over Times Square, past all the girlie shows and tittie bars. There was a great record store on Forty-second Street where I bought Lord Buckley records and Lenny Bruce records and Miles Davis records. We didn’t have access to that kind of edgy stuff in London, and that store was like hitting the jackpot. It was an adventure just walking into that place. Afterward, we’d lug all the shit we bought over to Tad’s Steaks for a great dinner—$1.98 for a steak and a baked potato. Right around the corner from the Paramount was a little coffee shop, which was the first time I ever had corned beef hash with an egg on top. And if we felt flush, we headed to Jack Dempsey’s bar for a bowl of Hungarian goulash. Just fantastic!

We were getting the royal treatment. We stayed at the Abbey Victoria on Seventh Avenue and it was the first time we each had our own room. Very posh. I couldn’t get over how the taps turned on in the bathroom and hearing the phone ring like it did in the American movies and getting take-out food. Take-out food! There was no such thing in England, not even a hamburger stand. There was a black-and-white TV in the room and I watched Johnny Carson every night.

That is, if I wasn’t already otherwise engaged. I have to hand it to American girls: They taught me a few things about sex that were outside of my advancing experience. It was obvious that American girls liked to fuck much more than their English counterparts. They were freer spirits and more experimental. English girls were shy. You know that play No Sex Please, We’re British? Well, that about sums it up. Trust me, it was a lot of work to get an English girl’s knickers off. So I was a willing and dedicated student. My education started with Goldie and the Gingerbreads, the first all-female rock ’n’ roll band signed to a major American label. They had a nice little groove. A lead singer with a big, throaty voice—Goldie Zelkowitz, who later changed her name to Genya Ravan and fronted Ten Wheel Drive. But I only had eyes for Ginger, the drummer, a fabulous creature who had all the right moves. She showed me what English women had only hinted at. Ginger couldn’t wait to get her knickers off for me. And talk about playing rim shots! Yeah, there was a lot to learn about American women.

One night, before we wrapped up the gig, Morris Levy decided to take us out to dinner. He’d caught our show a few times and obviously liked what he’d heard because he’d staked us to a few hours in a New York recording studio, where we laid down demos for about twenty-five Hollies songs. I suspected it wasn’t out of the goodness of his heart (a muscle insiders claimed had been left out of Morris’s body), and that something else was going on. He had something up his sleeve. Now, at dinner, he was laying it on thick. We went to a pretty posh place, the Roundtable, a Turkish restaurant with a tasty little belly dancer with a bare midriff down to there, whom we later wrote “Stop! Stop! Stop!” about. Nothing like a little navel-gazing to soften us up. Somewhere between dessert and coffee, Morris played his card. In an effort to expand his business interests, Levy offered us $75,000 for our music publishing. Now, in 1965, that was a lot of money. Twenty-five grand each for Tony, Allan, and me. We weren’t making anything that approached that sum. You can’t imagine how tempting it was to take it. But having dinner with Morris Levy was one thing; getting into bed with him was another altogether. We’d heard stories … how he put his name as writer on all the records Roulette released, how at one point he owned the phrase “rock ’n’ roll” and held the mortgage on Alan Freed’s house, how … nah, better not go there. But we heard other things that scared the shit out of us. (He’d have cut off my dick and put it on a keychain had he discovered I was sleeping with his secretary, Karen.) So we weren’t willing to sign with him, even for seventy-five grand, even though he was very kind to the Hollies. Later, he was eventually convicted of extortion and went to jail, so our intuition saved us from making an early mistake.

But, even so, it was cool meeting Morris. He was a gentleman thug, a great white, one of the early record sharks who put out a slew of legendary artists: Duane Eddy, Buddy Knox (check out “Party Doll,” a brilliant rockabilly hit), Lou Christie, Frankie Lymon, Dave “Baby” Cortez, and Joey Dee and the Starlighters (who in 1966 changed their name to the Young Rascals). A few years afterward, he went on a tear with Tommy James and the Shondells, so say what you will about Morris Levy, he knew a hit when he heard one and got it on record.

Man, we soaked up American culture like sponges. I loved it instantly. On the plane back, I remember being thrilled that we’d held our own with all the acts on that show. The other bands really dug the Hollies. We’d put tremendous energy into those two songs and we had done it. Now it was time to go home and raise our game to the next level.

THE LOCAL MUSIC scene was on fire when we got back to London. The Beatles were still undisputed kings of the top ten, but the Rolling Stones, whom we toured with in early 1964, had finally pushed their way onto the international charts. So had the Kinks and Gerry and the Pacemakers, the Dave Clark Five, and a few of our fellow Manchester bands—Herman’s Hermits, whose lead singer, Peter Noone, had worked the clubs with us, and Freddie and the Dreamers, whose lead guitarist, Derek Quinn, had been one of the Fourtones.

The tour we did with the Stones that year was a chilling experience. Hollies shows were pretty wild, but those Stones gigs were something else. Mayhem to the nth degree. The first time we played with them was in Scarborough, on the east coast of England, and that joint was jumping before anyone hit the stage. They were rough and loud—and fantastic. Different from the Hollies. There was a certain earthiness to the Stones. This was before Mick became Mick, before he started strutting and dancing. Didn’t matter. They had that sound, that attitude.

At the time, Brian Jones was already separating himself from the group. It had been his band at the start, but Mick and Keith had taken over, and you could tell that Brian was looking for a way out. He traveled with us, instead of with the other Stones, so it had come to that. The end for him was near.

Sometime afterward, when the Hollies were recording at Abbey Road, we learned the Stones were in a studio over on Denmark Street. In those days, sessions were pretty loose affairs, nothing like today, with all the paranoia and security. So Allan and I went over there to see what they were up to.

It was just a closet of a studio, about as big as my kitchen, and pretty crowded with all of us jammed in there—the Stones, Andrew Loog Oldham, and an intense little guy in wild red leather cowboy boots who turned out to be Phil Spector. They’d just finished making “Not Fade Away” and were working on the B-side, “Little by Little.” It was basically a throwaway, as most B-sides were, but they’d left a track open for percussion, so we all just started banging away on bottles and clapping. So for a few seconds, Clarkie and I were Stones sidemen.

We’d already toured with the Dave Clark Five in late 1964 and often, to my ears, we blew them off the stage. I didn’t hang out with Dave—and I didn’t particularly like him. He was aloof and condescending, just a mediocre drummer; Mike Smith was the standout musician in that band. They thought they were the Beatles—and they weren’t. Their songs just didn’t cut it.

The Dave Clark Five tour might have been a slog had it not been for the third act on the bill. The Kinks had just released “You Really Got Me,” and we loved the shit out of that song. All those power chords ripping through the intro, and Ray’s nasal honk. It was obvious that record was going to be a smash, so we begged the promoters to put them on the tour. Lucky thing, too, because those guys were rascals. The Davies brothers were actually talking to each other then, and they were prodigious talents, lots of fun. They had a unique sound that was rough, raw, and edgy. And they were working-class lads, like us. Loved to join us for a few pints and raise a little hell. On the last night of the tour, the Dave Clark Five were in the middle of their big number “Bits and Pieces”—tits and wheezes—when Eric Haydock and Pete Quaife, the Kinks’ bass player, took a huge bolt cutter to the stage power and cut those fuckers dead. Served ’em right.

We also did a tour with Peter Jay and the Jaywalkers, a Norfolk band that we loved playing with. They had a sixteen-year-old lead singer, Terry Reid, who became a dear friend of mine and a future songwriting partner. That kid had a great set of pipes. Terry, of course, turned down Jimmy Page’s offer to be the lead singer for his new group after the Yardbirds disbanded, a band that he’d call Led Zeppelin. Hey, shit like that happens all the time.

In any case, in 1965 things were happening at lightning speed on the rock ’n’ roll scene, and the Hollies shifted gears, heading into the fast lane.

Around this time, we got a call from our old friend and manager, Michael Cohen, the guy who owned the Toggery, where I had worked selling clothes. “This neighbor of mine says her son writes songs, and she’s driving me fucking crazy,” he said. “Every time I meet her, she asks if you’ll listen to his stuff. Look, I know he’s probably awful and it’s an imposition, but I like this woman. We’ve been neighbors a long time. So would you do me a favor? Just go down there and see what this kid’s about.” Michael was always a decent guy, so we said, “Sure, leave it to us. We’ll get her off your back.”

So we go over to the address he gave us—a semidetached house in one of the better neighborhoods in Manchester—to meet this so-called songwriter, a fifteen-year-old Jewish kid named Graham Gouldman. Now, we’re the Hollies—and we know we’re the Hollies, so we’re not going to make it easy on him, kid or no kid. We’re sitting in this posh, middle-class living room, slipcovers on the sofas, nice art on the wall. I threw Mr. Songwriter one of my best stony stares and said, “Okay, kid—give it your best shot.”

He picked up an acoustic guitar and started playing: “Bus stop, wet day, she’s there, I say, ‘Please share my umbrella …’” And it’s fucking fabulous! Tony, Allan, and I are cutting glances at each other, and … we know this is a hit song. We know what we can do with it, too, putting a Hollies spin on the tune.

We were pretty excited, ready to rush out of there and get our claws into this song, when I said to him, “Uh, before we go … got anything else?”

Before the words were out of my mouth, he started singing, “Look through any window, yeah, what do you see? / Smiling faces all around …”

We just stopped and stared. “Okay, kid—that’s two. We’re definitely taking those two. No question about it.” I shrugged out of my coat and sat down again. Obviously, we weren’t leaving the house so fast. “One more time, kid—anything else in your songbag for us?”

He said, “Well, I do have another, but I’m afraid I promised it to my friend Peter Noone.” And he launched into “No milk today, my love has gone away …”

Talk about being blown away. This fifteen-year-old kid wrote those amazing songs—I think they were the first three songs he’d ever written! It was incredible hearing them. And he eventually wrote “For Your Love” and “Heart Full of Soul” for the Yardbirds, “Listen, People” for Herman’s Hermits, and later he started the band 10cc. Nice little career, wouldn’t you say?

Before we even got back home, Tony had put a gorgeous twelve-string riff to the intro of “Look Through Any Window.” The song was made to be sung by voices like ours. All the harmonies were right there, and in no time we turned it into a Hollies song. We recorded it in less than two hours and knew we had an instant hit on our hands. Same thing with “Bus Stop.” We cut it in even less time, an hour and fifty minutes flat. Tony Hicks and Bobby Elliott arranged it. Tony added that fabulous guitar intro, and we laid down the entire lead vocal and harmony just once. Reduced it to two tracks before putting on another set of vocals, followed by the solos—Tony, Allan, and me. In the can.

“Look Through Any Window” came out in September 1965 and shot right into the top ten. It also broke into the top forty in the States, which put us on the map there once and for all. The residual buzz from our performance at the Paramount in New York, coupled with a hit single, launched the Hollies into the forefront of the rock scene. We were frontline troops in the British Invasion, right up there with the Beatles, the Stones, the Kinks, the Animals, and the Yardbirds.

We decided we were through making our name strictly on covering American hits. We were writing our own stuff now, and in the process we were adding to the sound of rock ’n’ roll. Okay, that might sound egotistical, but it’s true. It wasn’t just us, of course, but we were leading the way. There was a drift away from the simplest pop forms built on standard three- and four-chord progressions. New chord structures were being experimented with, innovative tunings, melodic patterns. We abandoned the trite moon-and-June rhymes, the hold-your-hand and just-one-kiss fluff that had governed lyrics for so long, in order to express ourselves musically. As songwriters, everyone’s perspective was expanding, and with it their imaginations, their command of language, their facility with rhyme. Just listen to some of the singles released in 1965: the Kinks’ “Tired of Waiting for You” and “Set Me Free,” “It’s My Life” by the Animals, the Zombies’ “Tell Her No,” “Satisfaction” and “Get Off My Cloud” by the Stones. Forget about where the Beatles were taking music. Creatively, the heavens had opened, and rock ’n’ roll had morphed into rock.

My personal outlook was also in transition. I was starting to become political and socially conscious, which would alter my perspective forever. I had been sheltered all my life, not so much by privilege but by limited circumstances. I hadn’t seen much of the world and I didn’t have much education, so I hadn’t read much about the world either. But living in London made it impossible to keep the blinders on. The people my age whom I encountered there were enlightened about the world situation, and I heard about it from all quarters: the escalation of the Vietnam War, of course, but also the first commercial nuclear reactor, apartheid and racial equality, the Profumo affair, military coups in developing nations, our diminishing environment, Rhodesia, Ghana, the Congo, Gambia. The postwar world was evolving in front of our eyes, and I found myself thinking about it in new and emotional ways. The issues at large began affecting me personally.

My initial response to this was music, expressing my views through song. And in 1965 we wrote “Too Many People” in answer to the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya, which the British had colonized in 1920. The situation there was a complete mess. So many innocent people had been slaughtered. It brought Jomo Kenyatta to the forefront of the African political system, and this scared England to death. Thinking about this, I began to realize that there were indeed too many people, too many rats, so to speak, and that population growth was an issue we’d better confront sooner than later.

With this song, I was starting to grow as a writer, starting to come round from the usual stuff the Hollies were writing and to view our stardom in an entirely new way. I felt we had a responsibility to use our public personae in order to speak out on important issues, to communicate them to our fans. It’s one thing to rail and rant one’s opinions, and quite another to put it across through music.

This was easy to do in 1965 as the city was changing into Swinging London. A full-scale cultural revolution was in progress, with youth and music dominating the scene, top to bottom. The boutiques on Carnaby Street catered to our lifestyle. Mary Quant was introducing miniskirts and Biba was around and Cecil Gee. The King’s Road in Chelsea had Granny Takes a Trip. Jean Shrimpton’s face was everywhere, along with Veruschka and Penelope Tree. Darling and The Knack spoke to us from the screen, cynical and sexy and angry, and Radio Caroline was broadcasting off the coast. It was all happening at the same time, and I loved every minute of it. I immersed myself in the whole explosive scene, getting a new kind of education, something that filled in a lot of the gaps.

In between our gigs and recording sessions, Rosie and I made regular visits to Manchester. Both of our families were there, and we tried to spend time with them every chance we got. On one of those visits in 1965, something shocking happened. I got on the bus to go from Manchester to Salford. I was sitting on the upper deck as we pulled up to a stop outside of Lewis’s department store on Regent Road. From my seat, I could see my mother at the bus stop. But not just my mother. She was with another man. They kissed passionately, at least more than in just a friendly, impersonal way. I ducked back out of sight while taking it all in.

That really threw me for a loop. I’d always assumed my parents had a pretty good marriage. They’d only ever had one argument that I recall, when my mother hit my dad with a wire brush and broke his skin. Otherwise, things were fairly routine in our house. I’d never seen real passion, but I’d certainly never seen signs of discord. I guess sometimes kids don’t know all that’s going on below the surface.

My mother got on the bus after the kiss, but fortunately she didn’t come upstairs. I sure as hell didn’t want her to know that I’d seen her. And since I knew where she was going to get off, I stayed on the bus a couple stops past our house and walked back to make it seem more natural. That gave me a chance to process what had happened, to reflect on events in my own chaotic life. I was kind of stunned that something like this was happening to my family, but it wasn’t completely shocking to me. I’d been in rock ’n’ roll for several years already, and I understood temptation. I’d sown a lot of wild oats. Hey, shit happens, people make mistakes. Including me, big-time. So by the time I got home, I thought, You know, that’s life.

A couple years later, I encountered an incident that helped put some pieces in the family puzzle. During a series of interviews with me and a few friends about the Manchester rock scene, Alan Lawson, a journalist, discovered that my younger sister Sharon was not my father’s daughter. You know how when siblings joke: “Look at her, she’s not a Nash. Really, look at her and look at us. Sharon must have been adopted.” It was a joke—but it turned out not to be a joke. Somewhere along the line my mother must have had an affair. It was absolutely shocking to me. So out of character for her. It was scandalous for those days, but my father always loved Sharon like his own daughter. Still, it had changed him. That and going to prison—I think he just lost his heart. He let his guard down and his immune system along with it, and he slipped into a steady decline.

In early 1966, my dad was in the hospital for some ailment or other. The Hollies were about to begin a European tour, but just before leaving I went to visit him, to give his spirits a boost. He was at Hope Hospital, where my sisters had been born, but after canvassing the ward I was unable to find him. That place was ghastly, overcrowded with beds twelve deep on either side, and I walked up and down the rows like a commander inspecting the troops. Finally, I spotted a figure the color of an orange. Something was going horribly wrong with my dad’s liver that was making his skin turn a hideous hue. He looked awful, so diminished, considering what a strapping guy he’d always been. I visited for a while, offered a few words of love, and promised to get back as soon as the tour was over in ten days’ time.

A few days into the tour, we were playing in Copenhagen when I got a call from Rose. “Your dad’s taken a turn for the worse,” she said. “I think you’d better come home.” I explained that we’d be home in three or four days, but she insisted. “No, it’s bad. You’ve got to come home right now.”

It was pretty late at night, and I couldn’t find a commercial flight from Copenhagen to Manchester, so I hired a two-seater plane to fly over the North Sea. Rosie was there to meet me at the airport and just said, “He’s dead.”

I was in complete shock. I knew my dad was sick, but I never thought he was going to die. He was only forty-six, hard to imagine, twenty-two years older than I was then. His death changed my life in so many ways. It’s why I believe, to this day, that you have to make every second count.

THINGS CHANGED MUSICALLY as well in 1966, as the Hollies’ star kept shooting skyward. We were in a groove. We continued to have one chart hit after another. Our fourth album was already in the works, and every one of our live shows was absolute bedlam, screaming teenyboppers, kids jumping over balconies, girls attacking us on our way out of the halls. The only stumble, if you can even call it that, was a cover version we did of “If I Needed Someone,” the George Harrison standout from Rubber Soul. I thought we made a damn good record of it. It was perfectly suited to our voices, with a smart three-part harmony that gave the song a soaring melodic virtuosity. Too bad George didn’t share our enthusiasm. In his wisdom, he felt compelled to give a press interview, in which he called our version rubbish. “They’ve spoilt it,” he said. “The Hollies are all right musically, but the way they do their records they sound like session men who’ve just got together in the studio without ever seeing each other before.”

Sometimes, even Saint George didn’t know when to keep his snarky views to himself. He felt as though he owned the fucking song and no one else had a right to interpret it. It wasn’t as though the Beatles had never done cover versions in their career. I should have reminded him of toss-offs like “A Taste of Honey” and “Mr. Moonlight.” Or his own anemic version of “Devil in Her Heart.” I guess I also should have taken my own advice and kept my mouth shut, but two weeks after his outburst, I was still seething. So I spoke with a reporter at NME and fired back: “Not only do these comments disappoint and hurt us, but we are sick and tired of everything the Beatles say or do being taken as law.”

In those days, tweaking a Beatle was like blaspheming the pope. But who the fuck cared. I was getting sick and tired of their holy status, the way they said whatever was on their minds, no matter whom it affected, right or wrong. All of London was in their thrall. And if you didn’t know Popes John or Paul, or at least drop their names in conversation, you might as well take the next train back to the provinces, over and out. Keith Richards said it best in Life: “The Beatles are all over the place like a fucking bag of fleas.” They were a great band and I loved their records. Every English group owed them a huge debt, but I had no intention of kissing their asses. (George and I became great friends later in life.) Besides, last I looked, the Hollies were holding down places on the same top ten as the Beatles, so pardon me if you don’t like our fucking record but keep it to yourself, if you please.

Although we remained friends, George’s outburst kind of cursed the record, and it stalled at number twenty-four—not a complete washout, but not our usual success. Pretty rare for the Hollies at this stage of the game. For obvious reasons, we needed to follow up with a killer single. There were plenty of things we’d written that were ready to go, but nothing that was a surefire hit. We kept coming up with songs like “When I Come Home to You” and “Put Yourself in My Place,” decent album cuts, but ultimately rejected as singles by Ron Richards, who didn’t think they were commercial enough to get instant airplay. We still hadn’t reached the point where we could crank out our own singles. Thankfully, Tony Hicks was committed to trolling the Denmark Street publishing houses, and he fished another winner out of their files. He picked up a little gem called “I Can’t Let Go,” written by Chip Taylor, who’d had a smash with “Wild Thing” by the Troggs and later “Angel of the Morning” and Janis Joplin’s classic “Try (Just a Little Bit Harder).” The song had a great hook we could work, and a verse with just the right touch of rejection:

Feel so bad, baby, oh it hurts me

When I think of how you love and desert me.

I’m the brokenhearted toy you play with, baby …

We made a classic Hollies record with it and shot right back onto the top ten, where it lodged all through the spring of 1966. You couldn’t avoid “I Can’t Let Go” if you listened to the radio. That March, we did a tour of Poland with Lulu. We opened in Warsaw, got into the Hotel Bristol, dumped our bags, turned on the radio, and the first thing we heard was “I Can’t Let Go.” That was mind-blowing, to start with. Then, a few minutes later, there was a tremendous commotion in the street below our window. I glanced out onto the square and saw a cordon of tanks, with troops massing on all sides and machine guns blazing. Holy fuck! We’re in the middle of a revolution here. Assume the position, Nash. Save your skin! I was just about ready to dive under the bed when I got a closer look at one of the generals. Seemed to me he looked a lot like Peter O’Toole. In fact, that fucker was Peter O’Toole. In a Nazi uniform. They were shooting a movie called Night of the Generals. Hey, no need to tell the rock ’n’ rollers in the hotel. Let ’em sweat it out behind the Iron Curtain.

The vibe wasn’t that much better once we hit the stage. Lulu opened for us, and she was great, a ballsy, brassy, sexy Scot who could really belt it. “To Sir, with Love” was screaming up the charts, so the crowd was waiting for her and turned on the juice. Halfway through her set, a young kid ran up the aisle with a small bouquet of flowers for her, only to be intercepted by the cops, who beat the living shit out of him. And we were powerless to do anything about it. This just added to my rapid politicization. I naturally despise bullies and people who utilize power over others. And as far as the cops go, I distrusted them mightily since the incident with my father. The cops in Poland were bullies and fascists, which cast a pall over our visit there. Don’t get me wrong: I have nothing against Poles, who were incredibly kind. In fact, I remember making love to an exquisite and quite adventurous Polish girl on that tour. But the police-state undercurrent creeped us out.

After Poland, I was ready for a little democracy on the half shell and welcomed another trip to the States. We got a tour there, about fifteen dates, playing ballrooms and doing some television stuff. I couldn’t wait to get over there again and soak it all in.

First time over I’d been overwhelmed by New York, but this time around it felt more like home. Even better. You could lose yourself there, be whoever you wanted, no questions asked. “Hey, buddy, you want a girl?” “How about a boy?” “A chimpanzee?” I wasn’t into boys or chimpanzees, but at least they were available if the urge arose. New York was one-stop shopping and incredibly discreet. Nothing like London, where everybody knew your business.

I hit the streets five minutes after we landed. Zoom! Right down to the Village. Just walked around, trying to soak up as much as I could. It was great. Nobody knew who I was. The club scene was amazing. It seemed like there was jazz on every corner. I hit the Vanguard and the Blue Note, caught shows with Mingus, Miles, Dizzy, and Gerry Mulligan. I went over to the Gaslight and saw the Spoonful. On Bleecker Street, I had my nose pressed against the glass outside the Village Gate, checking out the schedule, when I noticed some action behind me in the window’s reflection. A group of guys dressed like freaks were lingering by a building on the other side of the street. I recognized them immediately—the Byrds, one of my favorite American bands. McGuinn, Clark, Hillman … and the guy in the cape and weird leather getup, David Crosby. Suddenly, they all walked into this head shop. Now, I don’t presume to know what they wanted in such a place! But I didn’t have the balls to introduce myself. “Hey, I’m in the Hollies. Love the band, man. ‘Tambourine Man’ is a great record.” No one in America really knew who we were. Or if they did, they didn’t really give a shit. Besides, Crosby intimidated the hell out of me. He gave off this don’t-fuck-with-me vibe and seemed so unapproachable. I figured there was no point in knowing a guy like that.

We were staying at the Holiday Inn on West Fifty-seventh Street. A few days into our stay, I took a phone call from the concierge. “Mr. Nash, there’s a man in the lobby who would like to talk to you. He says his name is Paul Simon.” Now, the Hollies had just recorded “I Am a Rock” and did a pretty decent job of it. Paul liked it enough that he wanted to meet us. “Arthur and I are recording over at Columbia Studios,” he said. “You feel like coming down to the session?” Are you kidding me! This was Simon and Garfunkel, for God’s sake. They were putting together the Parsley, Sage, Rosemary & Thyme album and working on “7 O’Clock News/Silent Night,” with a news bulletin mixed in with the music. Brilliant stuff.

I learned a lot watching Paul and Arthur record. They weren’t just gorgeous singers, they were into the whole recording process. Nothing in that studio escaped their attention. One time, they said, “Hey, do you know this trick?” They would speed the track up and hit the snare drum in rhythm. Then, when they slowed it down, it produced a sound like pch-oooooewe pch-oooooewe. Brilliant. Another time, I watched their engineer, Roy Halee, take sixteen faders down at Paul’s last breath at the end of “Hazy Shade of Winter.” I’d never seen or heard anything like it before. Imagine how that looked to a rock ’n’ roll star who once wasn’t allowed to come within ten feet of the board at Abbey Road. The Hollies weren’t allowed to touch the faders. If we wanted more of a kick drum, I first had to go to Ron Richards, and then to an engineer, who would bring up the kick drum. In America, everything was so hands-on. I couldn’t take my eyes off what they were doing in the studio.

Later that week, Paul and Arthur invited me to accompany them to a gig at Texas A&M. On the plane down, I got a deeper understanding of who these men really were. They were far more worldly than I was. They talked about American politics, what was going on in Vietnam, about McNamara, about Dylan and his harmonica. Paul was reserved, but an intellectual Jewish guy who didn’t mind saying what was on his mind, with very strong opinions. I’d never met anyone like him. He and Arthur were both political, very outspoken. It wasn’t like that in England. The freedom to express yourself was so foreign to me—and so damn attractive. And the shows they did, with just one guitar, were stunning. Simon’s guitar work mesmerized me. Add to it those voices and those songs. I couldn’t take my eyes off their stage presence, and how the audience reacted to them. Their timing was incredible. Everything about them was turning me inside out. It was a whole new ball game for me.

Before we parted company, I asked Paul what he was listening to. He told me about a record called The Music of Bulgaria, which was a live recording of the Ensemble of the Bulgarian Republic made in concert in Paris in 1955. The music originated in the fields—in this case, the ladies who worked farms in Bulgaria, cutting down huge sheaves of wheat. To alleviate the everyday tedium, they would sing together, usually solo or two-part. In the early fifties Philip Koutev had put together the National Ensemble, comprised of the winners of local, regional, and national competitions. Koutev featured a women’s choir, for which he extrapolated these two-parts to many parts, producing a cappella harmonies unlike any I’d ever heard before: five-, six-, seven-part harmonies. As a lifelong student of such singing, it made my head spin.

I asked Paul where I could get this record, and he said, “I happen to have an extra one right here,” and he handed it over. I took it home, and it instantly became my favorite record of all time in terms of musical harmony. In my London apartment, I had an incredible sound system: two Brunell tape recorders in each corner. And when I played this record, the music went from the turntable into the first tape recorder, then through the second tape recorder into the speakers, so that everything was a microsecond off—but brilliantly so. I would get loaded, get a couple brandies and Coca-Colas under my belt, and play this record—loud. I would lie in the middle of the floor listening, and that’s how I turned people on to it.

I must have given away at least three hundred copies over the years. So in the early nineties, I got a call from Nonesuch Records to tell me that the Bulgarian Choir was going to do a short tour of America. Would I be interested in flying to New York to introduce them to the world’s press? I said, “Absolutely, I’m there.” There was a media event at the old Americana Hotel, where I got up and told the story of how Paul gave me the record and how, for thirty years, Croz and I had tried to spread this music throughout the world. Afterward, their translator came up to me and said, “Mr. Nash, the ladies would like to say something to you,” and they all gathered around me. I was expecting something in pidgin English: “Thonk yu, Meester Nosh, for takink and showink us to Amerka.” Instead, one of the leaders of the choir counted off, and they burst, in perfect harmony, into the end of “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.” “Do-do-do-do do / do do / da-do-do-do.” It completely floored me. It was such an honor that this choir that I had revered for so long had learned that song and was singing it back to me.

After New York and Texas, my head was in a different place, but it was nothing compared to our introduction to Los Angeles. LA was uptempo, vivace: the Beach Boys, the Ventures, Jan and Dean, the Mamas and the Papas. Hollywood! Blondes! I was in love with it before I ever set foot there.

Flying over the city, I was already sold. There were turquoise-blue pools spread across the landscape, the ocean licking across the western shore, sunshine as bright as klieg lights. Minutes after we got out of the plane, I climbed to the top of the nearest palm tree and told Clarkie I was never coming down. It was a metaphor he should have heeded.

Things got off to a wretched start. We had to cancel gigs and an appearance on the Hullabaloo TV show because our work permits weren’t in order. Again. A little cockroach from the musicians’ union came up to us right after soundcheck and said, “Cards, please?” Of course we didn’t have them. Tony told the guy to fuck off, but union guys are tough little bastards. “But we’re here,” we pleaded. “We’re all set up. We can’t play?” Nothing doing. We had to sit out those gigs, all of them, in fact, making the tour a complete washout. Fortunately, the Hollies were being thrown a party on April 27 by our American label, Imperial Records, and it promised to be a glossy affair.

The press party was the usual nonsense, lots of pretty strangers, too-fancy hors d’oeuvres, hearty corporate backslapping. A high-octane schmoozefest. But it was good to bump into Jackie DeShannon, one of my favorite songwriters. And I recognized Burt Bacharach and Sharon Sheeley, Eddie Cochran’s girlfriend, in the crowd. While we were refilling wineglasses, a young kid came over and started chattering at us. Hold on a second, squirt! With English people, you don’t just start talking—you introduce yourself. Not this kid. He launched right into a rap about the Hollies and it became apparent that he knew everything about us: every B-side we’d done, our middle names, things we’d forgotten about, like an ad we did for Shell Oil in 1964. It was obvious this kid was a real fan.

His name was Rodney Bingenheimer, later to become a famous deejay at K-Rock in Pasadena. And he was about to change the direction of my life.

“What are you doing after this party?” he asked.

Where were this kid’s manners? I didn’t know him from Adam. And I wasn’t about to tell him my plans. So I did what most English people do in cases like this: I turned the question back to him. “I don’t know,” I said. “What are you doing?”

“I’ve got these friends who are recording down the street, and I wanted to know if you’d like to come hang out in the studio?”

Turns out it was the Mamas and the Papas. Well, sign me up, baby. I loved “California Dreamin’ ” and “Monday Monday.” I knew those records backward and forward, and what a brilliant arranger John Phillips was. And I knew how great Cass and Denny sang. Sure, I was interested in hearing what they were doing. But I really went because I had seen the album cover and wanted to fuck Michelle. Hey, I wasn’t a bad-looking kid, and I was in the Hollies. I had as good a shot at her as any other guy. So off I went with Rodney Bingenheimer, ostensibly to check out the Mamas and the Papas.

As it happened, they were at Western Recorders in Hollywood, the scene of so many classic sessions with Nat King Cole, Elvis, Ray Charles, the Beach Boys, and Sam Cooke. Inside the studio, Michelle, John, and Denny were huddled around a microphone, putting an overdub on “Dancing Bear.” Michelle was every bit as advertised: gorgeous and sexy—but otherwise engaged—so I wound up talking with Cass. She was hanging around outside the studio when I got there and seemed eager to talk about British rock ’n’ roll, especially her idol, John Lennon.

“What do you think John would say about our music?” she wondered.

Loaded question. Lennon was a gnarly sort. Compliments from him were hard to come by. I wasn’t going to bullshit this woman, so I put it to her straight.

“He’d keep you at arm’s length until he’d trusted you enough to let you into his personal space,” I explained. “So he’d probably put you down at first.”

The minute the words were out of my mouth, Cass burst into tears. Holy shit! I’d only just met this woman and already she’s crying. “What did I say? What did I do?”

Little did I know that Cass Elliot had a huge crush on John, and that was the last thing she’d wanted to hear. Carefully, I skated around the awkward moment, so much so that when Cass recovered she asked me: “What are you doing tomorrow?”

“What is it with you Americans?” I said. “You always want to know what we’re doing? What are you doing?”

“I want to introduce you to a good friend of mine,” she said. “I have a feeling you guys are going to like each other.”

The next day, around noon, Cass pulled up to the Knickerbocker Hotel in a convertible Porsche, her long, honey-colored hair blowing aimlessly in the wind. She had the radio turned up loud: B. Mitchell Reed on KMET, one great song after the next. I slipped in beside her and off we went, snaking up Laurel Canyon Avenue to the top of the Hills, where Cass lived in a lovely ranch-style house, and we hung out for a while. Later, I would realize how much interesting hanging out went on there, but at the time I was just discovering what an incredible character she was—very complex, bright, talented, lonely, with a fantastic sense of humor that was at turns both sardonic and self-deprecating. Thanks to my meager self-education, I’d learned quite a bit about Gertrude Stein and her role in bringing people of different disciplines together, having meals, encouraging conversation. And Cass was exactly like that: Mama Cass. I got the feeling she sensed seismic shifts that were going on in my life—even before I did—and she immediately took me under her wing.

We jumped into the car and went halfway back down Laurel Canyon, pulling into a carport under one of those teetery stilt houses on Willow Glen. Upstairs, I could have sworn the place was deserted. There was absolutely nothing in it other than a couch, a chair, and a fabulous stereo system. There might have been a guitar leaning against the wall. Otherwise, there was a barefoot guy lying on his back on the couch, with the lid of a shoe box full of grass resting on his chest, and he was shaking it, separating the seeds and stems. I’d seen this guy before and suddenly realized: Holy shit—it’s David Crosby! He didn’t seem at all threatening, as he had in New York. In fact, he looked harmless and agreeable. (Probably the last time I could ever say that!)

Cass handled the introductions without telling him I was in the Hollies. I could tell he was slightly suspicious, wondering why I was with Cass, whether I was another starfucker trying to ride her fame. I could have been a roadie, for all he knew. David is, by nature, a suspicious man; you’ve got to really prove to him who the fuck you are and what you’re up to before he’ll even talk to you. And where Cass was concerned, he was overly protective. She’d been a dear friend for a long time, since she was a member of the Mugwumps and the Big Three back in her folkie days. Later, he’d gone on the Hootenanny tour with her as part of Les Baxter’s Balladeers, a second-rate folk-pop group modeled on the New Christy Minstrels. She, in turn, looked out for David, who was difficult, opinionated, stubborn, a punk, all the things that made it hard for you to make it in the business. But Cass recognized his talent and mentored him through the music industry. So they had a lot of history. He wasn’t about to let some English gigolo fuck it up.

The entire time we were talking, Crosby continued shaking the shoe-box lid, which was quite impressive. And without taking his eyes off me, he rolled the most perfect joint I’d ever seen. Now, full disclosure: I hadn’t seen many, and truthfully I’d never smoked one myself. The closest I’d come was at a gig we did in Morecombe, on the same bill with Donovan. I went over to Dono’s dressing room to say hello, and he and Gypsy Dave were smoking something that smelled strangely enticing. So I went, “Oh … sorry,” while backing comically out of the room.

Crosby had a suspicion I’d never smoked dope before and he seemed eager to initiate me. Honestly, no one was more eager than I was. There was no controlling my curiosity in those days. Even today. I wanted to see where marijuana might take me, how it could open me up. I was ready for any new experience, real or pharmaceutical. Little did I know at the time that Crosby had the best dope in Hollywood. In fact, he had the first sinsemilla, which was two or three times stronger than anybody else’s pot. And I proceeded to get ripped, from my tits to my toes. I was out of my mind. Man, I loved the feeling, and instantly I became a lifelong fan.

I’m not sure how long we hung out at Crosby’s. It seemed like days, but it was probably an hour and a half. Afterward, Cass drove me back to the Knickerbocker, where the Hollies were waiting for me. I was totally wasted, but in an incredibly good way, and couldn’t hide the fact that I was high. It was one of those cases, when you first smoke dope, where everything becomes insanely hysterical. “Look! A fly on the wall. A fly!” To their credit, the Hollies were amused—they were beginning to get used to my making left turns—but devoted to staying straight.

I didn’t see Crosby for another couple months, but Cass stayed on my radar while we remained in LA. It was obvious she was someone I really wanted to know better, and I saw her every chance I got. I was fascinated by her, especially the sweep of her influence. She seemed to know everyone who mattered, and her take on them was delicious. She showed me many wonderful things in a very gentle way, opening my eyes and my mind. I loved hearing her stories about the various groups she was in—how the Mamas and the Papas, who were all longtime friends, had gone down to the Virgin Islands on John’s American Express card and formed the group there, singing together while taking acid every day. I think she was always in love with Denny Doherty, but knew she didn’t stand much of a chance. Broken hearts and egos continued to get in the way. Cass’s life was a comedy and a tragedy and a life lesson all at the same time. If you really got to know her, it was impossible not to love her.

Crosby, too. I couldn’t shake the guy from my mind. He was such a free spirit, so irreverent. Just a different kind of guy than I’d ever met, an incredible character. He hated the status quo, said whatever was on his mind. You didn’t like it, tough shit. The energy he put out was incredible. Meeting Croz and Cass was a turning point for me.

And now things were about to get wild.

My father during the war

My mother, 1953 (© Graham Nash)

My father singing at a holiday camp, 1954

My father and his sister, Olive, 1953. One of my earliest shots. (© Graham Nash)

Me and Allan Clarke at school (© Graham Nash)

With Allan Clarke, the Guyatones, 1957. We were fifteen.

Playing my black Epiphone guitar with “Hollies” lettering, June 19, 1965 (© 1965 Harry Goodwin)

The Hollies at the Cavern in early 1963

The Hollies in New York City, 1967 (© Henry Diltz)

The Hollies, 1983 (© Henry Diltz)

David in Sag Harbor, 1969 (© Graham Nash)

Stephen Stills, “Captain Many Hands,” at the Caravan Lodge Motel, San Francisco, 1969 (© Graham Nash)

Self-portrait; Plaza Hotel, September 1974 (© Graham Nash)

Singing the chorus of “Marrakesh Express” at Heider Studio 3, LA, 1969 (© Henry Diltz)

The infamous disappearing house, Santa Monica Boulevard, LA, 1969 (© Henry Diltz)

The cover of my album Wild Tales, 731 Buena Vista West, San Francisco, December 26, 1972 (© Joel Bernstein)

My lyrics to “Immigration Man,” 1971 (© Joel Bernstein)

Photo from the cover of my boxed set, Reflections, Surrey, England, March 1973(© Henry Diltz)

The Mayan (© Graham Nash)

Sculpting Crosby, Miami, 1977 (© Joel Bernstein)

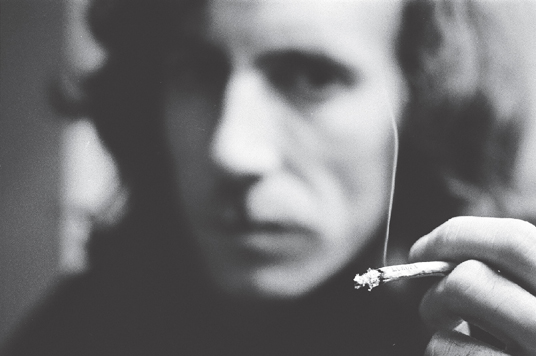

Tokyo, November 1975; the joint was rolled in a copy of the International Herald Tribune. (© Joel Bernstein)