26

As I stalk the arcades of the rue de Rivoli on my way to the lab, Lou Reed is droning into my iPhone buds that he’s waiting for the Man …

Today’s the day I’m putting down my zebra-striped four-inch-heel stiletto. I’ve been waiting for the man for nearly six weeks. We met once after the August holidays and now it’s late October. In fact, since we started working on the project six months ago, it seems I’ve done almost nothing but wait: Bertrand’s been away from Paris nearly half the time on various promotional jaunts, sourcing trips and holidays, and when he is in Paris, there’s always something more urgent on his agenda.

Granted, he’s the hottest indie nose-for-hire at the moment. Clients eager to capitalize on his talent and reputation are beating a path to his lab; he’s juggling several contracts and each time I see him, he tells me he’s about to take on more. Fair enough: he’s freelance, ambitious, eager to explore as many different registers as he can. But he’s got no agent, no PR, not even an assistant to help him handle increasing demands on his time and creativity, and I’m wondering whether he knows how to pace himself. More than that: I’m worried. I like the guy, respect the artist, and want neither to burn out. The angel in me wants to protect him; the muse is whispering that his art must be nurtured, not exploited, not even by himself. But my demon duende is slipping dark, mouth-burning anger between my lips. The fact that I can’t stand being pushed back into the crowd of those clamouring for his attention is a matter of pride, and since that can’t be helped I’ve got to swallow it. Yet it’s not just a matter of pride. What we’ve been doing is different from his usual gigs. The idea sprung up when our orbits intersected: spontaneously, gratuitously and, therefore, out of necessity. If there’s a blood accord in Duende, it’s because there is a bit of our lifeblood in the phials lining up on his shelf and their twins huddling next to my computer. But lately it’s been running a little thin.

I’m not just waiting for the Man. I’m waiting for the Moan, the one I let out when a perfume hits me at gut level. The Moan hasn’t come out, though that may be part of the protracted process of composition: dozens of mods before you can let go of any rational judgement and surrender to the beauty. Nevertheless, I can’t help wondering whether we haven’t taken the wrong fork somewhere. The last time we saw each other, Bertrand told me from now on I’d be seeing small tweaks, unless we wanted to change our course drastically.

And that’s just it. We’ve been focusing on tweaks; narrowing the scope to technical details: safe ground for him, not least, I suspect, because it’s a terrain where I have very little say and he can move quickly. Meanwhile, we’re losing sight of the thing that brought us together. It’s not just because he’s been morphing into a star over the past few months, the acclaim and contracts giving him constantly renewed motives for distraction. I’ve been thinking about my conversations with artistic directors, especially Christian Astuguevieille and Pamela Roberts, who both worked with Bertrand, but also Serge Lutens and Frédéric Malle. They all said the same thing. Ask yourself what the perfume wants. Trust the perfumer. Give him as much poetic licence as he needs. But make sure he stays focused on the story.

It’s time I heeded those lessons. I’m the one who should be keeping us on course yet practically all I’ve been doing so far is to mirror Bertrand’s decisions. When he asked me whether I knew what I wanted, I couldn’t answer, and that still smarts. When I mentioned that the few friends who’d smelled the various mods had all been saying, ‘This isn’t you,’ Bertrand kept repeating that he was perfecting the floral note. We’d inject more sensuousness afterwards. What could I say? I’m not the perfumer; I don’t know how it’s done. But however it’s done, I do know one thing: this is my story.

By the time I’m climbing the stairs to the lab, Nico is cooing, ‘I’ll be your mirror…’ into my earphones. Well, guess what, Mr D.? The mirror is about to talk back.

* * *

Of course, as soon as Bertrand greets me with a smile, whatever annoyance I’d been feeling towards him dissolves: he is nothing if not disarmingly likeable. It’s only after you’ve sparred with him for a while you realize he’s got a rock-hard core, some savagely protected part of him that can’t be budged and won’t open up. The hardness I see in the way he holds himself, legs slightly akimbo, ready to stand his ground; a density in his physical presence honed by years of tai chi. But Aries-versus-Capricorn head-butting would be unproductive: we’d both end up with a migraine. So as Bertrand downs a soup, a sandwich and a smoothie while I untypically pick at a salad I can’t even finish – I’ve swallowed my rant and it’s giving me a touch of heartburn – I steer the conversation towards my concerns about his career: flicking the cape, as it were, to attract his attention. He concedes I may have a point. I don’t press it. I am not my perfumer’s keeper.

Then we find our way back to our usual banter and I spill out six weeks’ worth of ideas and anecdotes, drawing him back into that little world two people create when they’ve been working together for a while, and he laughs and teases me for being so talkative – ‘You’re in love with words, aren’t you?’ – but I know from the twinkle in his eyes he’s enjoying the stories. For charm to operate, you’ve got to be charmed, and we’re both charmers: that’s our little unspoken war, I think. This may have been a game of dominance all along, one I’ve been letting him win out of sheer awe that this thing was happening at all. But underneath the comfort I feel chatting and laughing with Bertrand, that tiny nagging bite of anger is keeping me on edge. I’ve got a couple of things in my handbag that I’m waiting for the right moment to spring on him.

This time, I do know what I want. Or rather, I know what the perfume is asking for.

* * *

Up in the lab, Bertrand has two new mods to show me: numbers 15 and 16.

‘I’m focusing on the incense-blood note, maybe stupidly,’ he says as he’s preparing the blotters. ‘Maybe we need to work more on the base. Maybe this shouldn’t be a luminous perfume like I imagined at the start, with an almost cologne-like freshness. Maybe we ought to work on a headier orange blossom note…’

Good. He’s already moving towards my ideas without my having to nudge him. It makes it easier for me to formulate my critiques. For one, the banana was too strong in the last mods. When I’m in a jasmine alley, I get something oilier, spicier. And I’m still stuck on the N°5 mod we rejected last May because it wasn’t an orange blossom but a fierce, clove-laden lily. Re-reading my journal, I noticed that I was strongly drawn to it from the start and that I’d mentioned it several times afterwards. Yesterday, as I was testing mods 11 to 14, I sprayed on this fifth mod and found a quality to it that was missing from what Bertrand’s been doing lately, something that’s closer to the way I envision Duende.

When I mention this he just says, ‘Yeah, OK,’ before going back to the latest mods. He’s still trying to work out the warm blood note he associates with ‘duende, ardour, desire, so many things…’

‘And if you want, we could work spicy notes back in, a little bit,’ he concedes.

Indeed. This time I’m not letting him off the hook.

‘Speaking of spices, I’ve got N°5 with me. Would you like to smell it again?’

‘Gladly.’

I pull the phial out of my handbag and Bertrand dips in the blotters.

‘Oh yeah!’ he blurts out. ‘It’s really…’

‘… really what?’

‘Really woody. Really spicy. But you don’t smell the orange blossom.’

‘It’s the warmth of it I loved.’

Bertrand falls silent for a couple of minutes. Then:

‘It’s a good thing you brought back N°5.’

It is? I’m feeling rather smug now, but also a little bit scared. What if I’m derailing the whole process? No. I’m pretty sure I’m right about this. Still, I hedge:

‘I know it isn’t the story, but…’

‘But even so,’ he interrupts me, ‘the accord is beautiful. And it’s powerful, isn’t it? In fact, there’s a whole damn story in it!’

We do a side-by-side between numbers 15, 16 and 5: the latter’s green notes are different; they work better with the orange blossom, with slightly raw orange-tree-leaf effects.

‘You were right to bring back N°5,’ Bertrand repeats. ‘There’s a strong accord, even though it’s not one hundred per cent in the story.’

Guess I’m no longer just a human blotter, then.

Bertrand gets up suddenly to rummage through his files and flips through his sheaf of formulas. The woody note in N°5 came from a material called cedramber, which he used in his church incense, Avignon. He’d dropped it in the following mods. Now I understand better why I was so drawn to N°5 – yesterday, I even sprayed it alongside Avignon, so it seems I got the connection. The green top notes in N°5 were composed of angelica, tagetes and cassis base. Tagetes, a type of marigold, has dried banana and daisy facets. Cassis (blackcurrant) adds raspy, fruity, sulphurous tones. As for angelica (the green bits in Christmas cakes are the candied stalks of the plant), I’m mad about it and so is Bertrand. It’s got four different facets, he explains, a green dark resinous one that’s close to galbanum with almost stem-like effects, a spicy one that’s celery, a bit curry, almost hazelnut, and a musk note that is chemically identical to animal musk …

‘We’ll put angelica back in,’ he decides.

‘And it kind of works well with the religious theme because of the name.’

He raises his head from his formulas.

‘You know what? I’m going to go back to the base of N°5.’

‘That means you’ll be doing something completely different from N°16.’

‘Well, yeah. I’m completely going back to N°5 with its spicy note.’

‘You agree with me then?’

‘Yes, because N°5 has more character, more body, more accords than N°16.’

Should I be pushing my luck? I’ve scored high marks for sticking N°5 back under Bertrand’s nose – hey, Coco, could you be watching over me with your lucky number? As long as we’re shaking things up, I might as well get out exhibit number two: an 80s bottle of Habanita. Yesterday, I tried spraying on a tiny bit next to N°12 and Avignon to see how they combined, but Habanita just gobbled up my whole forearm.

Bertrand pulls a face.

‘The problem is you’re bringing this up so late in the game.’

Sheesh. I’ve been talking about Habanita for months. It’s called selective listening, darling: men are very gifted at that.

‘I don’t want Duende to smell like Habanita. It’s gorgeous but it’s not modern. What I do want is that burnished gold quality, that darkness you know how to work in so well…’

‘That Caravaggio chiaroscuro, as my friend Chandler Burr would say…’

The New York Times’ former scent critic, who considers Bertrand ‘a living Old Master of scent’, did indeed write that his Paestum Rose for Eau d’Italie was ‘rich and filled with meaning like the intimate opalescent blacks Caravaggio painted.’ Caravaggio is, along with Francis Bacon, one of Bertrand’s favourite painters …

‘Exactly. That darkness has got to be in our fragrance. The boy in the story smokes brown tobacco. It’s the smell on his fingers…’

Bertrand sniffs at his blotter of Habanita, eyebrows knitted.

‘I’m stunned.’

‘By what?’

‘By the natural tobacco effect. If this bottle is from the 80s they could probably still use tobacco absolute. Now to use a good tobacco that’s not banned because of the restrictions on nicotine … It’s rough going.’

Is he sold? I suspect he’s a little annoyed because, all of a sudden, Duende is going in many different directions, all of which interest him.

‘That’s a lot of information to take in all of a sudden…’ I half apologize.

‘All of a sudden … Can I associate all of it? I don’t know. It could be interesting. But I’d have to rebuild the formula completely. Rework the elements one after another, try to associate … How can I say? … the patterns of the accords, the orange blossom note as it is in 15 and 16, the lily note as it is in 5 and the Habanita note as I smell it here…’

He points to the bottle.

‘The tobacco?’

‘Oh yes, it goes with the story, completely! Tobacco, tobacco-stained fingers, and what have you!’

‘Tobacco-stained fingers in my knickers,’ I slip in, not wanting him to lose sight of the erotic aspect of the story.

‘In your knickers,’ he echoes in a get-your-mind-out-of-the-gutter tone, before adding thoughtfully: ‘This can be a beautiful challenge.’

‘So we’re going for that?’

‘We’re going for that. I’m sure we can get there. Now I have to break everything apart … We’re starting from scratch!’

‘Am I making you suffer with this?’ I say, a bit hopefully.

‘No.’

‘Good, because that’s not the point.’ (‘Yes it is,’ my demon duende whispers.)

‘I’m not afraid.’

‘Même pas peur!’ we utter simultaneously, laughing. It’s one of Bertrand’s pet expressions, something kids say in the schoolyard: ‘Not even afraid.’

‘In fact we’re not really starting from scratch,’ he says. ‘We’ll dismantle the puzzles, scatter all the pieces, take some from one puzzle, some from another, and re-assemble the perfume in a different form … bits of story that will shape another story.’

‘What a plot twist!’

‘It’s a plot twist, but that’s often how things go when you’re making a perfume.’

* * *

We take a breather by going over my write-up of the session during which we discussed incense: this has been our process ever since I started the journal. I add bits of research along with my thoughts to the transcripts, which allows Bertrand to follow the course of the development and put it into perspective. In this particular case, he’s both pleased and astonished to find out that his intuition about the equivalence between blood and incense is rooted in several myths, as well as in Catholic liturgy. He re-reads our conversation about his own obsession with the note and stares at the page for a while, nodding.

‘You’re right, you know … My creative process is a kind of therapy for all the suffering and frustrations of my childhood … I wasn’t mistreated, that would be an exaggeration, but our super-strict Catholic upbringing was quite oppressive. We’ve tried to break free from it and mostly we’ve managed to, at least the youngest siblings. Perfumery was one of the best ways to act it out.’

I am suddenly reminded of Serge Lutens’ droll, indignant tirade against bespoke perfumes – ‘I’m not a psychoanalyst!’ During lunch, I quoted it to Bertrand, who wholeheartedly agreed: his own experience as a bespoke perfumer ended abruptly after spending a whole day with a client. ‘At the end, I knew his life story but nothing about his tastes in perfume!’

Bertrand and I are far from psychoanalysing each other, though smells have a way of triggering sudden disclosures. But somehow it seems right that reading through the incense session and going back to the painful memories it summons – reopening the wounds of the incense tree, as it were – should come just as we’re dismantling what we’ve done up to now. Not just the formula, but the way we work together. Not quite a power shift, but greater exposure. Any creative process, when it is true and sincere, is like baring yourself to the bull’s horns. This is the first time that I lower my arms to bring the cape, and thus the horns, closer to my body … Though I did it in a roundabout way, showing him the things I wanted so that they would seem obviously right to him rather than asserting my will, I’ve exposed my desire, what I wanted for the perfume, and thus taken the risk of his saying no: I still haven’t shaken the feeling he could buck at any moment. A Capricorn goat may not be able to gore you like a bull, but he can knock you out cold or throw you out of the ring.

Still reading through my write-up, Bertrand gets to the point where he suggested adding an ash note.

‘Why don’t we put it in? The ashes of Christ, cigarette ashes … It’s all part of Holy Week, after all.’

Well, no, actually. Perhaps he’s willed his Catholic education out of his memory; still, he must have known at some point that Ash Wednesday is the first day of Lent, a full forty days before Easter and therefore, not part of Holy Week at all. The ashes are obtained by burning the palms of the preceding year’s Palm Sunday. They are a multi-secular symbol of penance used as far back as Ancient Egypt, as well as a reminder that we are dust and will return to dust. What they are definitely not are the ashes of Jesus: that he resurrects is kind of the whole point of Easter, not to mention Christianity.

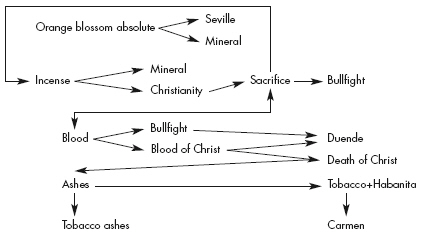

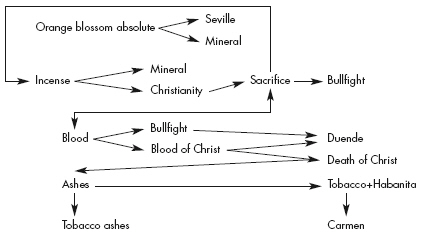

But I’m not about to dive into a theological debate with Bertrand because, right now, he’s doing something I’ve never seen him do, drafting some kind of flowchart. As I peer into it, I realize he’s laying flat the structure of Duende.

‘Do you often do this?’ I ask him.

‘Yes,’ he mumbles, still scribbling and drawing arrows.

I let him finish the chart before speaking again:

‘It’s as though something had clicked all of a sudden. As though you’d rethought the whole thing out.’

‘What’s crazy is that I’ve also rethought the whole formula.’

‘Well, that’s exactly what I wanted to do with you today. Shake things up.’

‘This isn’t about destroying what we’ve done. Absolutely not … it’s just…’

‘… clarifying our ideas…’

‘You know, creating a perfume is a labyrinthine process. At one point you say, “Shit, I’ve taken the wrong turn,” and you have to turn back a bit to take the right direction.’

‘At least the fact that there are two of us helps us get some perspective.’

‘That’s essential.’

Six months and eight sessions into the development of Duende, it seems I’ve finally taken on my role as a creative partner. I’ve been wandering in the labyrinth, but now I’ve found the red thread. No longer a muse but Ariadne leading Theseus towards the Minotaur …

The bull. The blood. The wounds of the incense tree. ‘The aid of the duende is required to drive home the nail of artistic truth,’ writes Lorca.

‘I’ll write down the formula right away before I forget anything,’ says Bertrand.

‘You won’t.’

‘I won’t.’