King George III was one of the few pre-20thC examples of a male British sovereign who had a virtuous domestic life. In 1761 the monarch bought Buckingham House from the Sheffield family. In 1775 he gave the building to his wife Queen Charlotte. The couple occupied it as their private residence; their official one continued to be St James’s Palace. In 1818 the queen bequeathed the House to their son the Prince Regent.

The prince acceeded to the throne as King George IV. In his new position he concluded that Carlton House, his pet architectural project in London, was no longer grand enough for him. At his behest, Buckingham House was remodelled by John Nash during the 1820s. The architect went over budget. Upon the accession to the throne of George’s younger brother, King William IV, the man was replaced on the scheme by Edward Blore. However, the work was not finished during the new monarch’s reign.

Queen Victoria had been raised in Kensington Palace. Following her accession in 1837, she moved into Buckingham Palace. She made it the principal royal residence in London. Her husband Prince Albert died in 1861. She spent most of the rest of her reign living away from the metropolis. She was able to do so because of the development of telegraphy and railways. The former enabled her to keep abreast of affairs in almost real time and the latter meant that she could swiftly return to the city whenever she needed to be there in person.

During the late 1860s and early 1870s there was a strong wave of republicanism in England. This started waning in 1872 after the monarch attended a service of thanksgiving at St Paul’s Cathedral. This was held to express gratitude for the Prince of Wales’s recovery from a case of typhoid. The residual popular image of the sovereign is one that was largely created for her during the later years of her rule by the Conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. In 1877 the premier had her crowned as the Empress of India.

In a way that his mother, Victoria, had not, King Edward VII appreciated that the public and ceremonial aspects of the monarchy were important to its maintenance. At his death he left the institution in a more vital condition than it had been at his accession. His son, King George V, was to retain his throne while several of their kinsmen were to lose theirs.

http://www.royal.gov.uk/TheRoyalResidences/BuckinghamPalace/BuckinghamPalace.aspx

The Royal Standard: At a glance it is possible to see whether the sovereign is in residence at Buckingham Palace. If s/he is then the Royal Standard flag is flown above the building. If the monarch is away then the Union Flag is substituted for it.

The Royal Standard is the personal property of the sovereign. It may be flown only where the monarch is residing. (‘The Royal Standard’ is a popular name for pubs - none of which are allowed to fly it.)

The Changing of The Guard: The Changing of The Guard takes place in front of Buckingham Palace. The ceremony involves the New Guard exchanging duties with the Old Guard. The ritual is accompanied by music that is played by a regimental band.

When the sovereign is resident in the palace, four sentries are present at the front of it. When s/he is away, there are two.

http://www.army.mod.uk/events/ceremonial/23241.aspx http://www.royal.gov.uk/RoyalEventsandCeremonies/ChangingtheGuard/Overview.aspx

Bearskins: Following the Battle of Waterloo (1815), the members of some British regiments took to wearing the bearskins hats that had previously been sported by their defeated opponents. The headgear is worn by members of the Coldstream, Grenadier, Irish, Scots, and Welch Guards.

The pelts are derived from Canadian black bears that are hunted under conservation quotas. A full-grown bear can make one to two caps. The females have glossier, smoother pelts. These are used to make the officers’ hats, while the rougher male ones are used for those of members of the other ranks.

The Queen Victoria Memorial (1911) stands in front of Buckingham Palace. In the taxi trade’s slang it is known as ‘the Wedding Cake’.

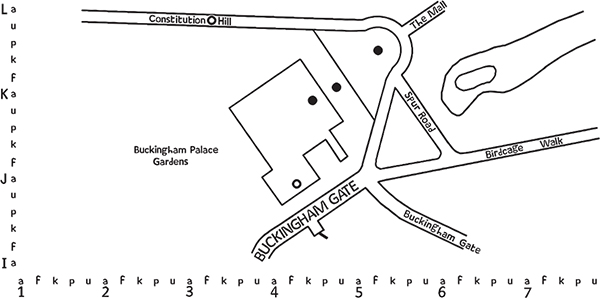

Direction: Birdcage Walk runs along the southern side of St James’s Park. Walk eastwards along it.

The Birdcage Walk aviary was established by King James I (d.1625). It was enlarged by his grandson King Charles II (d.1685).

Until 1828 only members of the royal family and the Grand Falconer could have their carriages driven along Birdcage Walk.

The Grand Falconers: The Dukes of St Albans are the Grand Falconers. Their graces are descended patrilineally from one of King Charles II’s illegitimate sons by Nell Gwynne. In 1953 the 12th duke proposed taking a live falcon to Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation. He was told that he should bring either a stuffed bird or nothing. Given these two alternatives, his grace opted for a third one of his own creation and did not attend the ceremony.

St James’s Park is the oldest of the royal parks in central London. Originally, it was a marshy meadow that was owned by the Hospital of St James, an institution that housed lepers. In 1531 the property was acquired by the Crown. The land was drained and laid out for King Henry VIII as a deer nursery that linked St James’s Palace to Whitehall Palace.

The park was used by King Charles II as a pleasure ground. The French landscape designer André Le Nôtre joined up a set of ponds to one another to create a rectangular body of water. The monarch used this for swimming in. His interest in ornithology is commemorated by the name Duck Island.

The wide variety of species of bird present on St James’s Park Lake owes much to the monarch. Many were effectively exiles from their native habitats as he himself had been for over a decade after his father Charles I had lost the Civil Wars of the 1640s.

There have been pelicans on the lake in St James’s Park since the 1660s. The colony is descended from a gift of some of the birds that was made by a Russian Ambassador.

Charles II appointed the popular exiled French poet Charles de Marquetel de St Evremond as the Governor of Duck Island. This absurdly-titled position honoured without antagonising the French court.

In the late 1820s the architect John Nash turned the formal lake into the informal one that dominates the centre of the park.

Possibly the most picturesque view in London is the eastwards one from the centre of the bridge that crosses the body of water. The crossing was designed by Eric Bedford, the Ministry of Works’s Chief Architect. (He was also architect of the BT Tower (1964).)

http://www.royalparks.gov.uk/parks/st-jamess-park

Squirrels: During the late 19thC and early 20thC there were a number of separate releases of grey squirrels. The first recorded one occurred in 1876 in the grounds of Henbury Park, an estate in Cheshire that was owned by the banker Thomas Brocklehurst. The animals were regarded as being ornamental. It was thought that they would live in small, isolated communities close to where they had been let loose. Ultimately, the case proved to be otherwise.

The greys carried with them the squirrel pox virus. The condition had minimal impact upon their health but was fatal to reds. Following the First World War the size of latter’s population crashed. People began to regard greys as being a pest. In 1939 it became illegal to import them.

www.forestry.gov.uk/forestry/redsquirrel www.squirrels.info/uk/in_uk.htm www.theredsquirreltrust.co.uk http://rsst.org.uk

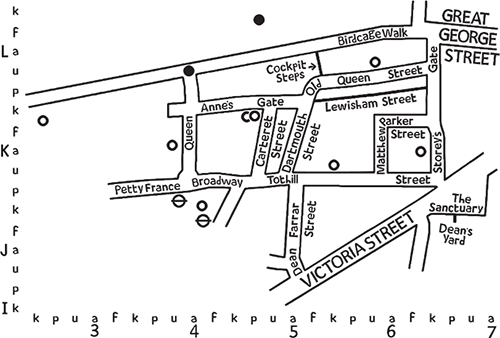

At the Treasury’s north-western corner is the entrance to the Churchill War Rooms.

During the Second World War Winston Churchill was not given to cowering in the complex. Atavistic urges caused the premier to be enthralled by air raids. Often during them, he would wander through St James’s Park bellowing out challenges to the Luftwaffe bombers overhead.

http://www.iwm.org.uk/visits/churchill-war-rooms

At the southern end of the eastern side of Horse Guards Parade is the Treasury Building (1912).

The Treasury’s interior is reputed to be most un-British in its style. There is a tale that it was designed to be a set of official offices in Bombay but that, due to a mix-up, the Indian government ended up with the building that should have been the British Treasury.

As a department of state, the Treasury is not always renowned for the financial acuity with which it handles its own affairs. During the 1990s the Cabinet Office had to take over the Treasury’s centre for information systems, the CCTA. It had emerged that the latter had been unable to balance the section’s figures for several years.

http://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/hm-treasury

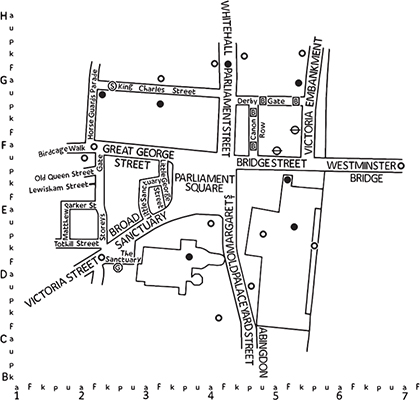

Direction: Continue eastwards into Parliament Square.

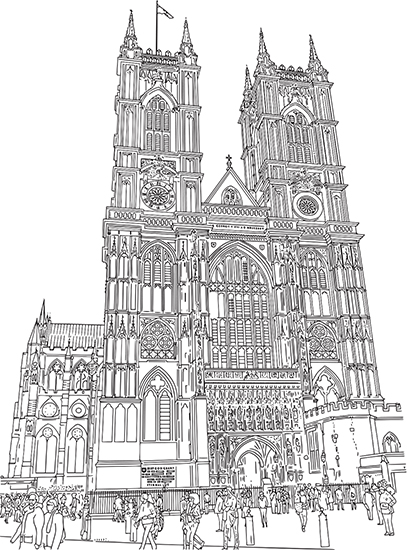

On the square’s southern side is Westminster Abbey.

Thorney Island was an isolated eyot that was bordered by the River Thames, Tyburn B rook, and a marsh. Upon it, King Edward the Confessor founded Westminster Abbey as a Benedictine institution. The building was consecrated in 1065. The monarch died the following year.

Edward was the last of the Anglo-Saxon kings. In 1161 he was canonised. King Henry III (d.1272) desired that his predecessor’s remains should have a resting place that was commensurate with his new status. Therefore, the Abbey underwent extensive reshaping. From 1269 until 1760 royals were buried in the aggrandised building.

During the Reformation the monastery was dissolved. However, the complex’s regal associations enabled it to metamorphose into being the Collegiate Church of St Peter, a royal peculiar. As such, it operates under the jurisdiction of a dean and chapter and is subject only to the sovereign. Some of its revenues were transferred to St Paul’s Cathedral (hence the phrase ‘to rob Peter to pay Paul’).

The Chapel of Henry VII was started by the Tudor king to commemorate his Lancastrian predecessor King Henry VI (d.1471). This was a way of indicating the new dynasty’s legitimate succession to the House of Plantagenet as the monarchs of England. The work on the Chapel was not finished at the time of Henry VII’s death. When it was completed during the reign of King Henry VIII, the son chose to dedicate the structure to his father.

The towers at the building’s weste rn end were late additions (1739). They were designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor.

http://www.westminster-abbey.org

On the square’s eastern side is the Palace of Westminster.

In the 11thC the principal residence of Edward the Confessor was built in Westminster. Parliament meets in the building that is its successor. Legally, the site is still a royal palace.

In the 14thC, during the reign of King Edward III, the two Houses of Parliament began to develop identities that were distinct from one another. The Commons’s sessions were held in the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey. The Lords remained in the palace, meeting in a chamber in the complex’s southern portion.

In 1512 the Palace was damaged by a fire. The subsequent repairs that were carried out to its structure were only partial. In 1530 Henry VIII saved himself the expense of further building work by moving the court a couple of hundred yards downstream to York Palace, which he renamed Whitehall Palace. He left behind the legislature and the judiciary.

On 16 October 1834 a fire was organised so that some redundant tally sticks could be destroyed. It ran out of control. Most of the surviving medieval complex burned down. The only parts of the old palace to survive were the Cloisters, the Jewel Tower, St Mary Undercroft (St Stephen’s crypt), and Westminster Hall.

http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/building/palace/architecture

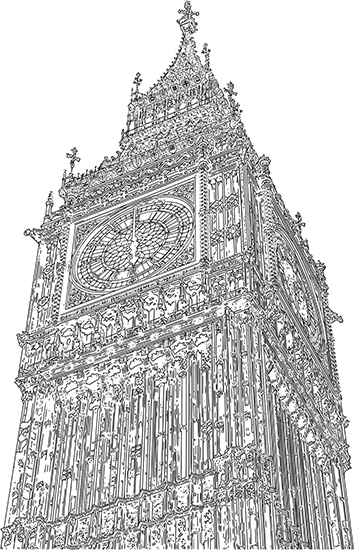

Big Ben: The bell that was intended for the Palace of Westminster’s St Stephen’s Tower (now the Elizabeth Tower) was cast near Stockton-on-Tees and then transported to London. The instrument was tested in New Scotland Yard. It cracked during this trial. Its metal was used by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry to cast a smaller bell that became known as Big Ben. This was rung for the first time in 1859.

The derivation of Big Ben’s name is uncertain. There are two leading contenders for having inspired its coining. The first is Sir Benjamin Hall, a notably stout official, who supervised the bell’s installation. (Hall’s wife, Lady Augusta, wrote The First Principles of Good Cooking (1867), a noted cookbook of the era. Her culinary expertise may have contributed to her husband’s ‘bigness’.) The other is Benjamin Caunt, a popular boxer of the day, whose nickname was Big Ben.

Whenever Parliament is sitting the Tower’s belfry is lit after dark.

Direction: Turn left into Parliament Street.

On the right is Derby Gate. The second home of Scotland Yard can be at its end.

The Derby Gate New Scotland Yard building (1890) was designed by Norman Shaw. The Met’s senior officers were accommodated in offices on the lower floors. The more junior a policeman was the more flights of stairs he had to climb.

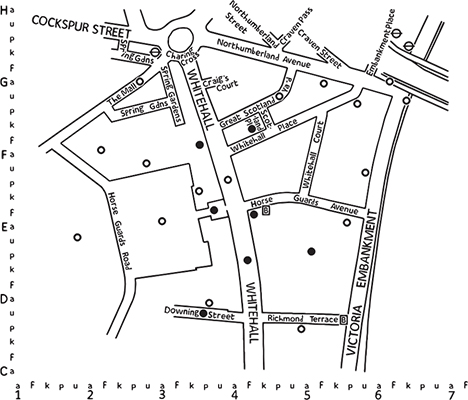

Direction: Parliament Street metamorphoses into being Whitehall.

In the centre of Whitehall is The Cenotaph (1920). This structure commemorates the dead of the 1914-1918 and 1939-1945 World Wars. It was designed by the architect Sir Edwin Lutyens and was first erected in plaster as a saluting point for the Allied Victory March of 1919. It was then rebuilt in stone and unveiled on 11 November 1920.

http://www.cwgc.org http://www.twgpp.org

Revolutionary Sod: The First World War and its immediate aftermath witnessed one of the principal socio-economic revolutions of British history. A sign of this was the manner in which belawned cemeteries for the burial of the slain were created. The graves were not located according to rank. The corpse of a colonel could be laid to rest next to that of a private.

However, Britain was Britain. There was a difference in the way that the lids of the soldiers’ coffins were fastened shut. The officers’ ones were secured with screws whereas those of the ranks were sealed by nails that were hammered into them.

During the conflict officers were proportionately more likely to be killed than were members of the ranks. This was because the formers’ uniforms were distinctive and they were armed with revolvers rather than with rifles. Therefore, Axis snipers were able to identify them on the battlefield and shoot them.

The road takes its name from a royal palace. For the most part, the complex lay between the present road and the Thames.

‘Whitehall’ is the senior, central strand of the Civil Service. Many of the ministries’ principal buildings are located along Whitehall or the streets to the south-west of it.

Until the late 18thC most government departments were small, and were housed in accommodation that was scattered across the West End and the City of London. The only sizable bureaucratic building was Somerset House (1786) on the Strand.

The politicians who headed the ministries were members of one or other of the Houses of Parliament. During the course of a working day they often had to be present in the Chamber, therefore, their ministerial offices needed to be near Parliament. As the Crown-granted leases along Whitehall expired, the government tended to hand the properties over to various offices of state. The 1890s were a decade during which the powers and responsibilities of the state grew. As a consequence, the size of the central bureaucracy expanded and a lot of building work was done for the government around Whitehall to accommodate the expanded ranks of officialdom.

Mandarins: Senior Whitehall civil servants are known as ‘mandarins’. An unlikely but possible derivation of this usage may stem from Sir William Chambers having been the architect of Somerset House (1786). As a young man he had travelled to China. Subsequently, he had settled in London in order to try to establish himself as an architect, he had drawn upon his experience of living in the Middle Kingdom to design a number of Chinese-style buildings, of which Kew Pagoda is a surviving example.

The Australian-born physicist and chaos theoretician Robert May was appointed to be the government’s Chief Scientific Adviser in 1995. It is reputed that his wife Judith once commented that he was so competitive that when he played with their dog he always played to win. When this remark was repeated to Lord May he responded by stating that, when it came to their encounters, the animal had an identical approach.

On the left is the eastern end of Downing Street.

While George Downing was an adolescent, he and his family emigrated from London to Salem, Massachusetts. His uncle John Winthrop was the colony’s inaugural governor. In 1642 the youth was ranked second in Harvard College’s initial graduating class. Three years later he left New England to serve as a ship’s chaplain in the West Indies. The following year he returned to England which was then in a state of civil war. He was appointed to minister to the religious needs of one of the regiments in Oliver Cromwell’s recently raised New Model Army.

Downing was both highly intelligent and very capable. His abilities drew him to the notice of some of the commander’s associates. They took it upon themselves to promote the young man’s interests in the advancement of their own. As a result, he was employed to perform a variety of secular tasks. In 1649 he was appointed to serve as the Scoutmaster-General of the English Army in Scotland. This position involved his heading the force’s intelligence operations. He fought at the Battles of Dunbar (1650) and Worcester (1651). That he was trusted by Cromwell enabled him to acquire wealth. In 1657 the Protectorate appointed him to serve as its envoy to The Netherlands.

Cromwell died the following year. He was succeeded as Lord Protector by his son Richard. The youth was not a man of the same calibre as his father had been. Politically, the Protectorate government began to collapse in upon itself. There was an appreciation that Britain might easily slip into a state of bloody anarchy. In 1660 George Monck, the head of the Army in Scotland, declared his support for the exiled King Charles II and marched his men southwards. Thereby, he cleared the way for the monarchy to be restored. Downing was an associate of the soldier. He offered to put his considerable skills at the disposal of the prospective regime. The proposal was accepted and a knighthood was conferred upon him. He was continued in his diplomatic position and was granted a remunerative sinecure as well as the grant of a plot of land that abutted the newer, western portion of Whitehall Palace.

The 59 officials who had presided over the state trial of King Charles I in 1649 had become known collectively as the regicides. The proceedings had ended with the monarch being sentenced to be executed. Downing had worked with some of the number on other matters. In 1662 he oversaw the arrest of three of them at Delft in South Holland. They were extradited back to England, where, in their turn, they were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. Of the trio, one had been the colonel of the New Model Army regiment of which Sir George had been the chaplain. The orchestration of these judicial murders led to Downing’s name carrying an overtone for ruthless self-interest that was to outlive him. He had not been trusted by the returned exiles, however, it was now clear to Charles II that the man had separated himself decisively from his old associates. He was now an independent agent who was not part of any faction. This political isolation and his ability made him a valuable resource for the monarch.

Downing’s admiration of the United Provinces’ politico-fiscal achievements did not prevent him from adopting a hawkish attitude towards the country. It is possible to attribute the start of the Second Anglo-Dutch War of 1665-7 to his actions although the substantive underlying cause was the two states’ colonial and commercial rivalries with one another.

In 1671 Charles appointed Downing to again be England’s diplomatic representative in The Netherlands. There is an argument that the king did this with the express purpose of having Sir George - whom the Dutch disliked profoundly - trigger another war between the two countries. If this was the case then the ruse worked. As the conflict commenced the knight was forced to flee back across the North Sea.

Downing had left his post without having had formal permission to do so. Therefore, he was lodged in the Tower of London for having. However, this may well have been a political expedient that covered the reality of what he had probably been instructed to do. The man was released after six weeks of incarceration and his talents continued to be well-regarded by the monarch. The previous Anglo-Dutch conflict had had an indecisive outcome. This one, when it finished in 1674, left England permanently as the principal party in the two states’ relationship with one another.

http://www.gov.uk/government/history/10-downing-street

On the eastern side of Whitehall is the Ministry of Defence Building.

The structure was designed by Vincent Harris in 1913. Appropriately enough, in view of its intended use, its completion was delayed by not just one World War but by two. The building was finished in 1959.

It has been claimed that the structure is mounted upon a vast rubber platform that was intended to absorb some of the shock if it is ever bombed.

It is reputed that, when the London Eye was erected across the Thames on the South Bank, a memo was circulated to the staff who worked in the building that requested that those of them who were using rooms on its riverside side should be careful about leaving documents where they might be photographed by passengers on the Eye, who might have cameras with telescopic lenses.

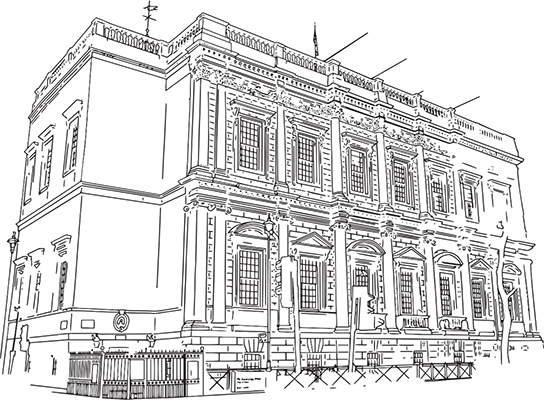

To the west of the northern end of the Building is the Banqueting House (1622).

The House is the principal visible remnant of Whitehall Palace. The building was designed for King James I by Inigo Jones. In 1698 a fire destroyed almost all of the complex. The House survived the conflagration. Subsequently, it was used as a royal chapel.

Originally, the building’s exterior was dressed with a warm, honey-coloured sandstone. In the 1830s it was remodelled so that it acquired its present neoclassical character. The masonry that was used to cover it had a bleak grey colour. Over the years, a number of the buildings along Whitehall were clad to resonate with it. As a result, much of the street developed an arid, impersonal tone.

The House was opened to the public in 1963. It is still sometimes used as a venue for diverse state occasions.

http://www.hrp.org.uk/BanquetingHouse

King Charles I: King Charles I lost the Civil Wars. At two o’clock on 30 January 1649 he was beheaded on a platform in front of the first floor of Whitehall Palace’s Banqueting House. A bust of the monarch on the building’s exterior marks the approximate point from which he stepped out onto the scaffold on which he was dispatched.

On the western side of Whitehall is Horse Guards (1758).

In 1649, during the English Republic, a guardhouse was erected in Whitehall Palace’s tilt-yard.

The monarchy was restored in 1660. King Charles II, as someone who had lost his father to the axeman, had a cautious aspect to his nature. The Horse Guards was the regiment that acted as his bodyguards. In 1663 he established it in quarters that adjoined the palace. Two years later a more substantial structure was erected. The present William Kent-designed building dates from 1758. (Only members of the royal family are allowed to drive through its central arch. The general public are free to saunter through it upon foot.)

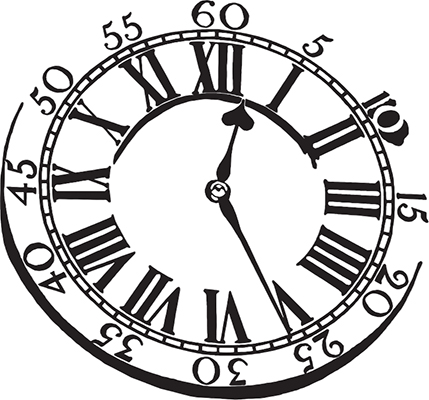

The Black Hour: The clock on Horse Guards’s Whitehall front has a black mark over its II/10 numerals. This commemorates the hour of Charles I’s execution.

On the western side of Whitehall is the Admiralty House (1788).

The House was built as the home of the Admiralty, the government body that supervised the Royal Navy. The building is no longer connected with the service.

The Conservative politician George Ward Hunt served as the First Lord of the Admiralty in the mid-1870s. The table in the Admiralty Board Room has a semi-circle cut into one end of it. This was created in order to physically accommodate the MP’s enormous belly. Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli assured Queen Victoria that the man ‘has the sagacity of an elephant as well as the form’.

On the eastern side of Whitehall is Great Scotland Yard.

In 959 the Scottish king King Kenneth II is supposed to have come to London to pay homage to King Edgar. It is reputed that the latter gave his brother monarch a house off Whitehall that stood on what was to become Great Scotland Yard. Whenever Scottish royalty came to London they stayed in the building. In 1603 the two crowns were united by the succession of the Scottish king King James VI to the English throne as King James I. Thereby, the residence’s purpose became redundant. Thereafter, the site was given over to other uses.

Peelers: In 1829 the Metropolitan Police Force (the Met) was legislated into existence at the behest of Sir Robert Peel the Home Secretary. The Force’s commissioners established their premises at No. 4 Whitehall. At the back of the building, in Great Scotland Yard, was its adjunct - the first police station. This occupied what had been the property’s servants’ quarters.

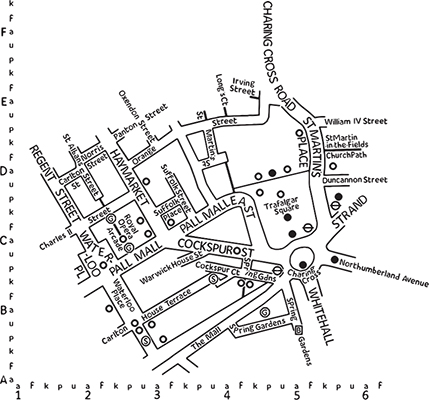

Between the northern end of Whitehall and the southern side of Trafalgar Square is a road that is called Charing Cross.

The equestrian figure of King Charles I (1633) is the oldest of the royal statues that stand in the West End. It was sculpted by Hubert Le Sueur. In terms of scale, the effigy makes the monarch out to have been a taller man than he was (4ft 7in (1.4m)). The compliment is delivered discreetly through the placement of the 6ft (1.83m)-tall representation upon a horse.

Following Parliament’s victory in the Civil Wars and the execution of Charles in 1649, Oliver Cromwell ordered that the figure and its steed should be sold for scrap. John Rivett acquired them and was soon carrying on a lively trade in selling artefacts that he declared had been cast from their metal.

The monarchy was restored in 1660. Subsequently, it emerged that the brazier had carried out a deception. He had buried the effigy in his garden. It was exhumed and sold back to the Crown for £1600, which furnished him with a healthy profit. King Charles II (a genuine 6ft in his hose) had it re-erected (1675) on what had been the site of Charing Cross. The spot had been used for the executions of those regicides, who had not been dead or in exile when he had returned to England.

Northumberland Avenue enters the eastern side of Trafalgar Square.

Northumberland House (1605) was the townhouse of the Percy Dukes of Northumberland. Despite its great beauty and the opposition of the Percies, the building was pulled down in 1874 and replaced by Northumberland Avenue. The road was intended to provide access for a bridge across the Thames. The crossing was never built.

Most of what is now Trafalgar Square was once occupied by the Royal Mews. This was a complex of buildings and yards that acted as the royal stables. The medieval structures had been created for keeping hunting birds in. Following a fire in 1534 the facility was expressly rebuilt to accommodate horses. A new main stable block (1732) was designed by William Kent.

In the early 19thC the architect John Nash drew up the Charing Cross Improvement Scheme. This envisaged the square. It was part of his larger plan for beautifying the West End. This was centred upon the creation of Regent Street. In 1830 Kent’s stable block and the rest of the Mews were demolished. Nash died before he could see his greater plan put into effect.

http://www.london.gov.uk/priorities/arts-culture/trafalgar-square

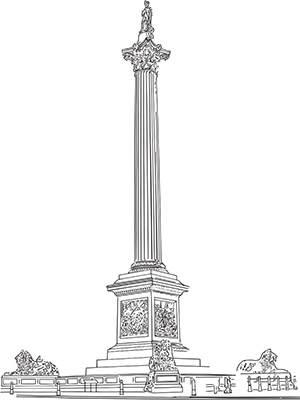

Nelson’s Column: At the Battle of Trafalgar (1805) the naval commander Lord Nelson vanquished a combined Franco-Spanish fleet. The victory gave Britain and her allies the initiative in their struggle against Napoleon. It was widely celebrated at the time. However, the construction of Nelson’s Column (1849) did not begin until 1839, 34 years after the sea battle had taken place. That a structure was erected owed something to inter-service rivalry and the building of the Army-funded Duke of York’s Column (1834) on Carlton House Terrace. Nelson’s admirers were able to exploit the prior completion of his grace’s support to commission a structure that was taller than it.

The statue of Nelson that stands on top of the Column is over seventeen-feet-tall. The commander’s actual height was nearer to five feet (1.52m) than it was to six (1.83m).

Pigeons: Originally, pigeons were a species of coastal bird. With time, they extended their range inland. London’s buildings provided them with a substitute for cliffs.

In 1996 it was reported that the police were investigating the mysterious disappearance of hundreds of pigeons from Trafalgar Square. A possible cause was a man whom passers-by had seen trapping the birds in baited boxes. It was speculated that he might have been selling their carcasses to chefs.

One theory forwarded at the time was that the warmth of the previous summer and autumn had led to a larger crop of berries and nuts than usual. This meant that wood pigeons were able to feed themselves in woodland. Therefore, they did not need to break cover to search for sustenance in fields. ergo, they were less likely to be shot. This had created a rise in the price that restaurants were prepared to pay for pigeon meat, and thus an incentive for a spot of urban poaching.

A £50 fine for feeding pigeons in Trafalgar Square came into force in 2003. Subsequently, the number of the birds in the Square was estimated to have declined from 4000 to 200.

The National Gallery: The National Gallery (1838) spans the northern side of Trafalgar Square. The institution houses the national collection of Western Art.

After making a Grand Tour of Europe in the 1780s, Sir John Leicester decided to focus his art purchases on contemporary British works. In 1823 he offered his paintings to the government as the nucleus for a state collection. The then Prime Minister Lord Liverpool declined the tender. The same year John Julius Angerstein, an insurance tycoon and a major art buyer, died. The idea of establishing a national gallery by buying the man’s collection was promoted by both King George IV and the art patron Sir George Beaumont. The following year the government acceded to their lobbying. The foundation of the National Gallery was aided by the Austro-Hungarian state’s timely repayment to Britain of a war loan. The institution effectively came into being when the House of Commons voted money for the purchase of 38 paintings from Angerstein’s estate. Beaumont added to these some works from his own collection. The body was housed during its first decade in a building on Pall Mall.

In 1834 the Gallery moved into its present home. Given the building’s prominent location, it is a relatively unimposing structure. William Wilkins, its architect, was under considerable pressure to produce an ‘economic’ edifice; he was required to use the columns that Henry Holland had created for Carlton House even though they were inappropriate for his design. When the structure had been completed, it engendered numerous adverse comments. Initially, the Gallery occupied just part of the site, the rest of it accommodated the Royal Academy of Arts.

In 1854 the government purchased Burlington House in Piccadilly. It was decided that the building should house the Academy and a number of learned societies. This gave the Gallery considerably more space in which to display its works. During the following year Parliament made its first grant to the body of money that it could spend on acquisitions. With the opening of the Tate Gallery in 1897 much of the National Gallery’s British collection was transferred there.

http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk

South Africa House: South Africa House (1935) stands on the western side of Trafalgar Square. The building is occupied by the South African High Commission.

For many years a continuous 24-hour a day, 365 days a year anti-Apartheid demonstration was mounted outside the building. During the protest’s duration, many passers-by were probably more aware of the protestors than they were of the fact that the building that was being picketed served a diplomatic function.

http://southafricahouseuk.com/

Direction: Turn right (north-eastwards) into Strand.

On the left side of Strand, on the north-eastern side of the junction with Agar Street, at No. 429 Strand is Zimbabwe House (1907).

The building was redesigned by Charles Holden for The British Medical Association. On its second storey façade there are The Ages of Man, a series of sculptures that were created by Jacob Epstein. It was the American’s first high profile commission in Britain. There was an initial outcry about the nudity of the figures, however, the voiced concerns were soon placated.

The South Rhodesian High Commission acquired the building in 1937. The chaps then underwent some radical amendments. It was claimed that they had suffered frost damage which meant that there was a danger of passers-by being struck by a falling appendage, and that the changes had been made in order to try to avert such an eventuality.

http://zimbabwe.embassyhomepage.com http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/sir-jacob-epstein-1061

Rhodesian Righteousness: Rhodesia’s political leaders issued a unilateral declaration of independence in 1965 that sought to end the country’s colonial relationship with Britain. Subsequently, the state’s parliament passed legislation that deprived black Rhodesians of the franchise. The BBC made a number of broadcasts about the matter. The African regime took exception to the character of these.

The Rhodesian High Commissioner in London called upon Sir Hugh Carleton Greene, the Corporation’s Director-General. The diplomat stated that the public body, under its charter, was obligated to furnish balanced coverage between right and left. Greene agreed that such was the case. However, he continued that the duty did not extend to providing one between right and wrong.

On the right is Durham House Street. In the mid-16thC a series of great mansions spread out westwards from the City of London along the Thames’s northern shore. The street stands on part of what was London townhouse of the Bishops of Durham. The Crown acquired the property in the 1530s.

Sir Walter Raleigh: Walter Raleigh came from a background that, while it had some connections to the court, was not closely associated with it. Among his kinsmen were several experienced sailors. As a young man he served both at sea and as a soldier. In the early 1580s he decided to try to establish himself as a figure within the court. He was able to gain access to it and succeeded in catching the interest of Elizabeth. He was an ardent bibliophile and had already developed a considerable intellectual hinterland. This compounded his other appeals for her.

The favours that Elizabeth conferred upon Raleigh included the use of Durham House, the former London residence of the Bishops of Durham. However, for all the charms that the West Countryman was able to exercise upon the queen, he was an incomplete courtier. His often acid tongue riled many of those with whom he spent time. Such people came to look upon him as being an intruder within their community.

King James I did not like Raleigh and gave the property back to the Bishop of Durham. The Spanish Crown had long regarded Sir Walter as being a pirate. Therefore, the knight became a pawn in Anglo-Hispanic state relations. Ultimately, the game went against him and he was executed in 1618.

The Adelphi: In the mid-17thC housing was developed on the Durham House site. This swiftly degenerated in being a slum. The mid-18thC project to redevelop the land for more salubrious housing was instigated by the four Adams brothers (hence the name The Adelphi, the ancient Greek word for ‘brothers’). The most famous of the sibs was the architect Robert Adam.

The enterprise ran into financial difficulties. (One of the factors that may have discouraged potential residents was the Adams’ plan to rent a cellar complex beneath the development to the government as a gunpowder store.) In 1773 a lottery was authorised by Parliament to rescue the enterprise from the financial straits into which it had fallen.

By the 1870s the area began to be redeveloped anew. Some of the original Adams buildings survived this process.

The Royal Society of Arts: William Shipley was a drawing master from Northamptonshire. In 1754 he founded the Society for The Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce. Six years later the body mounted the first art exhibition to have been held in England.

In 1774 the institution moved into its home, a Robert Adam-designed building that was part of the Adelphi development. The Society’s hall features a mural that was created by James Barry over the years 1777-83. When the painter started on the work, he seemed to be about to put his stamp on London’s art world. When he finished it, he was a spent force.

In 1847 the Society received its royal charter. The body played an important part in organising the Great Exhibition of 1851, the Great Exhibition of 1862, the series of exhibitions that took place in South Kensington during the mid-1880s, and the Festival of Britain in 1951.

In 1852 the Society mounted the first exhibition of photography. Two years later it held the first educational exhibition. In 1856 the body started holding educational examinations; this led to the establishment of the RSA Examinations Board. Eight years later the Society awarded its inaugural Albert Medal to Rowland Hill the postal reformer. In 1867 the body erected London’s first blue plaque in Holles Street; this commemorated the poet Lord Byron. In 1908 the Society received permission to term itself the Royal Academy of Arts.

Direction: Continue north-eastwards along Strand.

On the right is The Savoy Hotel.

The impresario Richard d’Oyly Carte is best remembered for having persuaded the librettist W.S. Gilbert and the composer Arthur Sullivan to collaborate with one. Their operettas were systematically pirated in the United States. Carte responded by staging the premiere of The Pirates of Penzance (1879) in New York City. The profits from the production helped to finance the construction of The Savoy Theatre, which opened in 1881.

During a trip that Carte made to America, he was impressed by the material comfort of the hotels in which he stayed. He decided to utilise The Savoy Theatre’s profits to build the best hotel in London. In 1889 the Savoy Hotel opened. It was the first hotel in Britain to have fitted electric lights and to have such a high proportion of private bathrooms. By then Carte’s association with Gilbert had deteriorated. The latter sued the former. Subsequently, the men were reconciled to one another. However, as a result of the legal proceedings the librettist and the composer’s relationship became permanently strained. That they were able to continuing working together derived in very large part from the tact and organisational skills of Carte’s wife Helen.

In 1898 the Savoy opened The American Bar. This was the first place in London to serve ‘American’ cocktails. During the 1920s the hotel enjoyed the patronage of numerous wealthy trans-Atlantic visitors, leading it to be dubbed ‘the 49th State’.

http://www.fairmont.com/savoy-london/

An Unsuppered Beak: Oscar Wilde had entertained a number of rent boys in The Savoy Hotel’s Room 361. Following his arrest for gross indecency, the presiding magistrate was moved to comment, ‘I know nothing about The Savoy, but I must say in my view the chicken and salad for two at sixteen shillings is very high. I am afraid I shall never supper there myself.’

The Autowidow: Marie Marguerite Laurient was a striking-looking Parisienne prostitute who had a number of wealthy men as her clients. In 1917 and 1918 she allowed the future King Edward VIII to partake of her charms. She wed ‘Prince’ Ali Kamel Fahmy Bey, a wealthy Egyptian, who was a decade younger than she was. Their short-lived union proved to be highly dysfunctional. In 1923, while they were staying at The Savoy, she shot her spouse dead.

The ‘princess’ was put on trial two months later. Her past was not a matter of public knowledge. She had in her possession a number of letters that the Prince of Wales had written to her. A deal was brokered between his aides and the autowidow. They, with some assistance from figures within Scotland Yard, sought to ensure that she would not be convicted. Whether it was as the result of their efforts or not, she was acquitted of the charge.

The Departed and The Departing: There were a number of apartments in The Savoy complex that were permanently occupied by individuals. One of the residents was the movie actor Richard Harris. As he was dying, he was carried out to an ambulance that was parked outside the hotel. He is reputed to have proclaimed to a party of arriving tourists, ‘It was the food!’

On the right, at No. 100, is Simpson’s-in-the-Strand.

The restaurant is famed principally for its roast beef. The establishment was founded in 1828 by Samuel Reiss as the Grand Cigar Divan, a coffee house that sought to provide a congenial atmosphere in which chess could be played. Its patrons included Howard Staunton, the world’s leading chess player of the mid-19thC. John Simpson, a caterer, joined the business in 1848. It was he who moulded the eatery that it is largely to this day. In order that games should not be interrupted joints of meat were taken to players’ tables on silver-topped trolleys where they were carved.

The original Simpson’s premises were demolished in order to accommodate the widening of the Strand. In 1904 the restaurant re-opened under the wing of the Savoy Hotel; the playing of chess was no longer encouraged by the management.

http://www.simpsonsinthestrand.co.uk

Direction: Continue north-eastwards. Cross Lancaster Place. On the right is Somerset House.

Somerset House was one of the great riverside mansions of the 16thC. It was owned by the 1st Duke of Somerset (d.1552). He was the uncle and Lord Protector of the young King Edward VI (Henry VIII’s only son). In 1552 the building passed into the Crown’s possession.

The property was never used as the sovereign’s residence. This may have stemmed from its being located too close to the City for any monarch to have felt comfortable there. Instead, it was a place where royal wives and widows lived.

Queen Charlotte was the last royal consort to dwell in the residence. In 1775 her husband King George III gave her Buckingham House. She moved there.

Sir William Chambers was appointed to reconstruct Somerset House (1786) so that it could provide lodgings for various departments of state. It was the first purpose-built set of government offices in Britain. A number of learned societies were also accommodated within the complex.

The two wings are 19thC additions.

http://www.somersethouse.org.uk

The Courtauld Gallery: The Courtauld Gallery occupies the north wing of Somerset House.

The Courtauld Collection was born out of a visit that the textiles magnate Samuel Courtauld made to an exhibition that was mounted at the Burlington Fine Arts Club in 1922. This seeded in him an interest in art. Nine years later he founded The Courtauld Institute. This was the first academic body in Britain that taught art history as a discipline in its own right. It became part of the University of London.

Courtauld’s personal collection bore the hallmarks of the systematic caution of an experienced businessman. It has been opined that the works that he owned reveal little of the person. He bought according to informed advice. He made no spectacular purchases - never spotting an underrated painter - but then he made no major blunders - the collection did not have any weak paintings or weak artists represented. He bought art from the previous century in a mature market.

The Collection is strong in the fields of the French Impressionists and the Post-Impressionists. Courtauld was the leading British collector of these two schools. While he was still alive the businessman gave the Institute part of his personal collection. His will left it much of the rest. The Collection has acted as a magnet for subsequent bequests.

http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/index.shtml

Direction: Continue north-eastwards along Strand.

On the left, in the middle of Strand is St Mary-le-Strand.

A church stood on its site as far back as 1147. The Church of the Nativity of Our Lady & The Innocents was pulled down by the Duke of Somerset. Its stone was used to help build the Lord Protector’s mansion Somerset House. The churchless parishioners were allowed to worship in the Savoy Chapel, which is located on the other side of Lancaster Place.

St Mary-le-Strand (1717) was the initial place of worship to be built under the Fifty New Churches Act of 1711. It was the first public building that James Gibbs had designed. (The architect was a Roman Catholic but kept quiet about the fact. This was because of the prevailing sectarianism that then existed in some strata of contemporary society.)

Direction: Continue north-east-eastwards along Strand. On the left, in the middle of the road is St Clement Danes.

The Church of St Clement Danes survived the Great Fire of 1666 unscathed. However, its structural infirmity led to the building, with the exception of its tower, being demolished. The new edifice (1680) was designed by Sir Christopher Wren. An extension (1720) to the tower was the work of James Gibbs.

http://www.raf.mod.uk/stclementdanes

Direction: On the right is the northern end of Essex Street.

In 1587 the 1st Earl of Leicester asked Elizabeth that he might be allowed to resign from his office as Master of the Horse. Then, also at his behest, the monarch appointed his stepson the 2nd Earl of Essex to the vacant office. The young peer soon caught her attention. It became apparent to Leicester that the youth had the potential to act as a means of undercutting Sir Walter Raleigh’s place within the monarch’s regards.

Essex was not the same type of favourite as Leicester was. The latter was of the same generation as Elizabeth. He appreciated just how close England was to slipping back into the anarchy of civil war. His actions were always tempered by a knowledge of how thin the socio-political veneer was and of how much there was at risk. Essex was too young to have this worldview. As a result, ultimately, he did not possess the self-restraint that their actions were informed by. There may have been a maternal aspect in the queen’s relationship with him. This would have made it different from her attitude towards her contemporaries. She and the earl developed an intense bond that upon occasion ignited into their having blazing rows with one another.

Essex had a talent for first riling Elizabeth and then being able to induce her to forgive him. In 1590 he secretly married Sir Francis Walsingham’s daughter. When the queen learnt of the match, she was furious. With time her rage subsided. However, the new Countess of Essex was never given any scope to become a figure within the court.

Essex had witnessed the martial phase of Leicester’s career. This may have been a factor in his desire to establish himself as a military figure. He was aware of how the older courtiers were dying off and that eventually such would be the queen’s fate. He regarded himself as having the potential to become the arbiter of England’s future course with regards to Europe.

In the mid-1590s it became apparent to Essex that Elizabeth wished to disengage England from her involvement in European affairs. This ran counter to his vision of himself. She and the Cecil family were unreceptive to his opinion that Spain was preparing to launch another invasion attempt. Madrid had no such intention, however, some Spanish sea captains, in a private capacity, raided the Cornish coast. This seemed to vindicate the earl’s view.

Preparations for a counterstrike were set in motion. The peer was appointed to serve as the venture’s joint commander. In June 1596 the force captured Cadiz. Essex had developed a belief that his troops would be able to retain control of the city. This would commit England to being embroiled in Continental affairs. However, this plan was dashed when it proved to be impracticable to hold on to the settlement militarily.

Following the expedition’s return, it became apparent that much of its plunder had gone missing. This antagonised Elizabeth. She had the Cecils launch an inquiry into the matter. Essex felt that his achievement was not being given its due. However, Spain’s intention of avenging the raid soon allowed the earl, in his military aspect, to strut as England’s defender.

Once the venture had started, nearly everything that could go wrong for Essex did go wrong. Contrary winds delayed the fleet’s departure. During the wait disease broke out in the encamped army. As a result, the number of soldiers who ended up embarking was reduced. Therefore, a raid upon a mainland Spanish town was no longer viable. The undertaking turned into being solely a maritime one. The earl’s nautical expertise was minimal. He could have addressed this shortcoming by ceding de facto command of the endeavour to his deputy. He did not do so.

Essex and Raleigh learnt that a Spanish fleet was transporting a cargo of silver from Latin America to Europe. Its capture would have provided a means of salvaging the situation. However, they missed encountering the flotilla by a few hours. When the expedition returned to England, it was apparent that the earl’s military reputation had suffered a setback. His rivals at court were already of the view that he needed to be humbled. The enterprise had furnished them with a large body of material with which they could try to undermine his standing with the queen.

The earl’s importance in Elizabeth’s emotional life was as great as it had ever been. However, to him she was the factor that was preventing him from realising what he took to be his destiny. In July 1598, during a Privy Council discussion of Irish business, she made a disdainful comment about something that he had said. His response to this was to turn his back upon her. This was a major breach of court protocol. She responded to it by boxing him about the head. In turn, he reached for his sword handle. The action of a fellow councillor prevented him from unsheathing the weapon. An impasse set in. This was broken when he succumbed to an illness and she felt herself to be free to express her concern for his well-being. In early September he resumed attending conciliar meetings.

A revolt in Ireland had broken out in 1595. It was led by the 2nd Earl of Tyrone. The English state required that the insurrection should be suppressed. Essex wished to embark upon further military adventures in Europe but found himself to be blocked upon the score by the Cecils. Elizabeth conferred the Lord Lieutenancy of her western kingdom upon the earl. It was not an appointment that the peer welcomed. He sailed to Dublin. During the course of the spring and summer of 1599 it became apparent to the peer that he had insufficient men and resources to be able to resolve the matter by force of arms. The queen’s letters to him made clear her scorn at his conduct. In the end, he met with the rebel leader. The two men agreed a truce between their forces.

Essex knew that back in England his every action was being given a negative interpretation by his rivals. He decided to deal with the situation directly. As Lord Lieutenant, he needed official permission to be able to leave the country. He crossed back over the Irish Sea without having applied for this. He met with Elizabeth on 28 September. She instructed him to explain his conduct to the Privy Council. The monarch and the favourite were never to lay eyes upon one another again.

Essex underwent a physical and mental collapse. At one point, he was close to death. He recovered. With regard to his conduct in Ireland, in early June 1600 he was tried by the Council, in its aspect as the Star Chamber court. The body resolved that he should be sequestered from his offices and placed under house arrest at the queen’s pleasure.

Following Leicester’s death, Elizabeth had conferred upon Essex a grant of the customs on sweet wines that his stepfather had enjoyed. The cash that this bestowal had generated had become central to his finances. The lease for the concession was due to expire soon. As his movements were controlled, he was unable to exert his charms upon the queen to induce her to renew it. If she did not do so, the reduction in his income looked as though it would cause his vast debts to bankrupt him.

Essex’s personal following contained a wide range of people. One element that was present within it was composed of military adventurers. These men advised the earl that he should resolve the matter by force of arms. There were also alternative, moderate counsels being offered to him. In October the queen declined to renew the grant. The earl allowed himself to be persuaded that he should stage a coup d’état.

In January 1601 Essex led a body of 300 armed men eastwards into the City of London. His purpose in doing so was to try to trigger a rising against the Crown. The settlement’s inhabitants were not inclined to rebel. The earl’s men were soon countered militarily. He and a rump of them succeeded in making their way back to Essex House. There, they were laid siege to by forces that were loyal to Elizabeth. When the beleaguers placed cannons ready for use against the building, the peer bowed to the inevitable and surrendered.

The following month Westminster Hall hosted Essex’s trial for treason. He was convicted of the charge. Six days later he was beheaded within the Tower of London. His corpse was interred within its Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula.

Dr Nicholas Barbon: Dr Nicholas Barbon was the son of the wealthy leather merchant Praise-God Barbones, who was the prominent republican MP from whom the ‘Barebones’ Parliament of 1653 acquired its soubriquet. At the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 the father was imprisoned in the Tower of London but was eventually released on bail. In the meantime, the son stayed out of danger’s way by studying medicine at Leyden in The Netherlands.

Dr Barbon returned to London. He soon revealed that he had a talent for property development. In 1674 he bought Essex House, demolished it and developed Essex Street and its sisters upon the site.

In about 1680 Barbon created a de facto form of fire insurance. He also wrote a number of works on economics: he addressed rent in Apology for The Builder: or A Discourse Showing The Cause and Effects of The Increase of Building (1685); he argued that imports underwrote exports in A Discourse of Trade (1690), which was based upon his experience of business in The Netherlands; and he discussed the recoinage in A Discourse Concerning Coining The New Money Lighter (1696). In his will he left instructions that his executor should not pay any of his debts.

Direction: Continue north-east-eastwards along Strand. On the right, at No. 216, is Twinings.

Daniel Twining was a weaver in Gloucestershire. In the 1680s he concluded that the county’s cloth industry was in decline. Therefore, he and his family moved to London. His son Thomas served an apprenticeship with an East India merchant. This left the youth with a knowledge of tea as a commodity.

In about 1706 the younger Twining became the owner of Tom’s Coffee House in Devereux Court. This was one of London’s leading coffeehouses. It drew much of its custom from the lawyers who worked in the nearby Inns of Court. The establishment was noted for the savants and wits who chose to congregate there. The proprietor drew upon his knowledge of tea to ensure that it developed a fine reputation for serving the beverage. He prospered and went on to set up a business that wholesaled tea and coffee.

http://twinings.co.uk http://www.twinings.com

On the left, on the northern side of Strand, are the Royal Courts of Justice.

The complex houses two of the three branches of the Supreme Court - the High Court and the Court of Appeal. The cases that are heard within complex are usually civil law actions. Its entrance regularly serves as a backdrop for television news stories about major lawsuits.

From the late 13thC until the 19thC, the chief courts of English law sat in Westminster Hall during the legal term. Out of term, they sat at a variety of other places. The Palace of Westminster burned down in 1834. Subsequently, it was decided the superior courts should be relocated so that they should be nearer to the Inns of Court. The Royal Courts of Justice (1882) were built to provide permanent year-round accommodation. The facility received the courts that had been housed previously in Westminster Hall, Lincoln’s Inn, and the Doctors’ Commons.

The 1000-room, G.E. Street-designed complex was paid for with Chancery funds that had not been claimed. The site stretches back to Carey Street. 350,000,000 bricks were used in its construction. There are 60 court rooms. They account for about an eighth of the building’s internal space.

In 1880 the pressures imposed by overseeing the erection of the Royal Courts contributed to the death of Street. That he had died prematurely is indicated by the way in which his corpse was interred in Westminster Abbey. He was the only architect who had not been knighted to receive this posthumous distinction.

http://www.justice.gov.uk/courts/rcj-rolls-building

Badminton: It is believed by some that, when the building is closed to the public, its high-ceilinged Central Hall is sometimes used as a badminton court by people who work there.

On the right, at No. 222 Strand, are the former offices of The Tribune, a left-wing weekly publication.

In autumn 1943 the journalist Eric Blair left the BBC in order to become the literary editor of The Tribune. He wrote its as I Please column under the pseudonym ‘George Orwell’.

In his new position, Orwell gave out some reviewing work to Peter Vansittart, an aspirant writer who had been educated at a public school. Upon one occasion the pair were drinking in a pub near to the paper’s offices. The experienced hand gave the neophyte a lecture in which he stated that ‘with an accent like that and a tie like that you will never be accepted by the working classes’. The impact of this counsel was undermined when the barman addressed Vansittart by his forename and Orwell as ‘Sir’.

Direction: On the left, in the middle of Strand, is The Temple Bar Memorial.

The Temple Bar marked the City of London’s western edge. The first known reference to it dates from the late 13thC. Originally, the Bar was a gate.

On state occasions that require the sovereign to be present in the City, s/he asks the Lord Mayor of London for permission to enter its boundaries and then receives the Sword of State from the official, which is returned to her/him at the end of the visit. The ceremony dates back to 1588 when Queen Elizabeth I went to St Paul’s Cathedral to give thanks for the defeat of the Spanish Armada.

The Temple Bar arch (1672) was designed by Sir Christopher Wren. The structure, like the Monument in the City’s south-eastern corner, symbolised London’s rebirth in the wake of the Great Fire of 1666.

With time, the arch became a barrier to the free flow of traffic. In 1878 it was dismantled and stored in a builder’s yard.

Direction: At the Memorial, Strand metamorphoses into being Fleet Street.

At the start of the 18thC the newspaper industry emerged in Fleet Street grew out of a well-established local printing tradition.

Until the 1980s newspaper printing was carried on in central London. It was possible for such large-scale industrial activity to be engaged in at the heart of a great metropolis because the principal movement of goods (paper rolls and printed newspapers) took place at night when the streets were largely free of traffic.

During the decade technological advances ended the need for newspaper offices to be physically close to their printing plants. The papers relocated to parts of London where property was cheaper to occupy. ‘Fleet Street’ continues to be used as a general name for the newspaper industry.

Direction: On the right, between Nos. 16 and 17 Fleet Street, is a gateway to the Middle Temple.

The Middle Temple and the Inner Temple are Inns of Court. The ‘Temple’ refers to the crusading Order of the Knights Templar, which was dissolved in 1312 (in a particularly unsavoury instance of Anglo-French co-operation). The ‘Inner’ of the Inner Temple refers to its geographical relationship to the City of London, it being nearer to the City than the Middle Temple was. (There was an Outer Temple that was developed for other uses before the end of the 16thC. Essex Street now stands upon what was part of its site.)

In the mid-14thC another Order, the Knights Hospitallers, leased the property to some practitioners of Common Law before themselves being suppressed by King Henry VIII in 1539 as part of the Reformation.

http://www.middletemple.org.uk http://www.innertemple.org.uk

Direction: On the left is the Church of St Dunstan-in-the-West.

Queen Elizabeth I: The statue of Queen Elizabeth I (d.1603) that supervises Fleet Street from the Church of St Dunstan-in-the-West was carved in the 16thC. It was created to be part of the decorations that ornamented the City of London’s Ludgate gateway. The portal was demolished in 1760. The figure was then placed upon the church’s street front.

In 1929 the prominent suffragette Lady Millicent Fawcett set up a trust for Her Majesty’s maintenance and repair. This arrangement made her the only statue in London to enjoy a private income.

http://www.stdunstaninthewest.org

Direction: On the right, at No. 48 Fleet Street, is El Vino.

El Vino was founded in 1879 by Sir Alfred Bower. In 1923 the business acquired its Fleet Street premises. The wine bar was the haunt of generations of journalists and lawyers. It has a reputation for being fussy about dress and it used to be awkward about serving women. In 1982 the Court of Appeal made the firm accept that women, if they so chose, could stand at its bar and be served there.

Direction: Continue eastwards. On the right the northern end of Bouverie Street joins Fleet Street.

Much of central London has been owned by a number of aristocratic dynasties for centuries. Pleydell-Bouverie is the surname of the Earls of Radnor. The family are descended from Huguenot merchants. They own a number of properties in the area to the south of the eastern end of Fleet Street.

A past Earl of Radnor is reputed to have remarked that he would not open his country house to the public because ‘The people who come around here might be very nice, but you would n’t want to see and hear them all the time. I am told that you can even smell them and eventually your house takes on an odour like a railway station.’ In part, it was the income generated by the Pleydell-Bouveries’ London estate that enabled the late peer to afford to keep his stately home private.

www.nationalgallery.org.uk/about-longford-castle

Direction: Continue eastwards. On the right the northern end of Whitefriars Street joins Fleet Street.

In medieval times ecclesiastical institutions were subject to Canon Law and exempt from civil jurisdiction. It was possible for a person to take sanctuary on church precincts and remain immune from civil prosecution just so long as s/he remained physically on that property.

Whitefriars was a Carmelite priory that occupied the district that lay between the Thames, Fleet Street, the Temple, and Whitefriars Street. The dissolution of the monasteries (1535-40) did not remove the property’s Canon Law-derived immunity. In 1608 King James I issued a charter that confirmed the inhabitants’ privileges. The authorities could only enter the land using a writ that had been issued either by the Privy Council or by the Lord Chief Justice. The area became a ghetto that was inhabited by outlaws and criminals. The first known reference to it as ‘Alsatia’ was in Thomas Shadwell’s 1688 play of the same name. In 1697 the land became subject to the City of London’s jurisdiction. However, it continued to be extremely lawless for several decades.

Direction: On the left, at No. 145 Fleet Street, is Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese.

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese is a pub that was rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666. It was one of the lexicographer Dr Samuel Johnson’s (d.1784) favourite haunts.

Direction: Continue eastwards. On the left, at Nos. 135-141 Fleet Street, is the former home of The Daily Telegraph newspaper.

Hugh Massingberd was from a background that made him socially an aristocrat in Ireland and economically middle-class in England. An autodidact, he became the editor of the reference works Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage and Burke’s Landed Gentry.

In 1986 he was appointed to be the obituaries editor of The Daily Telegraph newspaper. At the time, The Independent was being launched and The Times was regarded as dominating the field. Massingberd, in parallel to James Ferguson’s innovations at The Indy, reinvigorated the form through a mixture of scholarship, satire, and accuracy.

Massingberd claimed that he was working in the tradition of John Aubrey (d.1697), having been inspired to do so by a one-man show about the antiquarian’s book Brief Lives that the actor Roy Dotrice had mounted at the Criterion Theatre. This had made him realise that reading obituaries should be fun. He was partial to blimpish military types and socially elevated fainéants. Private Eye magazine dubbed him ‘Hugh Massivesnob’. In 1994 Massingberd stepped down from his editorial post.

Massingberd adored food. If a waiter listed what was on offer for breakfast, the fellow would wait until the end and then nod his head. The attendant would then inquire what it was that he would like, to which the journalist would reply, ‘All of them.’

The obituaries that were written of Mr Massingberd have been run.

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries

Direction: Continue eastwards. On the right, St Bride’s Avenue joins Fleet Street.

St Bride’s was one of the four churches that rang out the City of London’s curfew. During the 16thC the parish became associated with the printing industry. The Great Fire of 1666 destroyed the medieval St Bride’s. A new building (1678) was designed for the site by Sir Christopher Wren.

During the 19thC and 20thC the church tended to the spiritual needs of members of the newspaper industry. In 1940 the building’s structure was severely damaged by an aerial bomb. Subsequently, an archaeological investigation revealed that its crypt had been built above the remains of a Roman house. The church was reconstructed. In 1957 it was rededicated.

Wedding cakes: St Bride’s Church’s spire (1703) inspired William Rich (d.1811), a local pastry cook, to devise the tiered wedding cake.

Direction: Continue eastwards. On the right, at No. 99 Fleet Street, is The Punch Tavern.

In 1841 The Punch Tavern was the birthplace of the magazine Punch. The publication was launched by the engraver Ebenezer Landells and the writer Henry Mayhew. They were reforming Liberals who sought to combine humour and political comment.

As the later 20thC progressed, the organ came to be increasingly identified with dentists’ waiting rooms. In 1992 the magazine was closed. It was relaunched in 1996 but closed for a second time in 2002.

Direction: Continue eastwards. Ludgate Circus straddles the now subterranean River Fleet.

It is possible to have a fleeting glimpse of the Fleet on Hampstead Heath, where it rises. Until the 19thC the King’s Cross area was known as Battlebridge after a bridge that spanned the river (and a battle that was never fought). Holborn probably derives its name from the bourne (or stream) having created a hollow.

Turnmill Street in Clerkenwell was named after the mills that existed along its length until at least the 1740s. These harvested the energy of the Fleet’s flow to grind a variety of materials into powders.

In 1733 the section of the Fleet between Holborn Bridge and Fleet Bridge was arched over. Farringdon Street was built over the river north of Ludgate Hill in order to provide a venue where the Fleet Market (the relocated Stocks Market) could be held. The watercourse has left its mark in terms of local street names - Turnagain Lane led to the river, Old Seacoal Lane recalls how ships from the coalmining region of north-east England could be brought upstream to unload their cargo, and Fleet Street itself.

New Bridge Street (1765) covers most of the river’s final stretch. The river’s waters enter the Thames.

Direction: Continue eastwards up Ludgate Hill. On the left the southern end of Old Bailey joins the Hill.

From 1783 to 1868 public executions were conducted at the northern end of Old Bailey next to Newgate Prison. In 1807 the murderess Elizabeth Godfrey’s dispatch attracted a crowd of 40,000 people. A stampede occurred during which 100 people died.

http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/about-the-city/what-we-do/Pages/Central-Criminal-Court.aspx http://www.oldbaileyonline.org

Direction: Continue eastwards. On the left is the Church of St Martin within Ludgate. On the building’s exterior is a plaque that commemorates Ludgate gate, one of City of London’s principal gateways.

A small prison formed part of Ludgate gate’s structure. During the Wars of the Roses Sir Thomas Malory’s association with the Yorkists led to his spending spells incarcerated in London. It was during one of these that he composed Morte d’Arthur, the first major literary work in English to tell the story of King Arthur and The Round Table. The tale is a foundation myth. In most cultures such tales are triumphant. Its end contains a large element of dystopnianism.

The knight switched sides and became a supporter of the Lancastrians. As a result, he was locked up again. However, the Yorkists’ were eclipsed in 1470 and he was freed. He died the following year

The Demolition of The City Wall and Gateways: Until the middle of the 18thC the wall was kept in good repair. However, Britain’s great military successes during the Seven Years’ War led the City authorities to express their confidence in their own safety. This took the form of demolishing the city gateways and much of the wall. The stone was used to build other buildings with. For the most part, these, in their turn, have also been demolished.

Direction: Continue eastwards. Ludgate Hill, at its crest, become the western end of St Paul’s Churchyard.

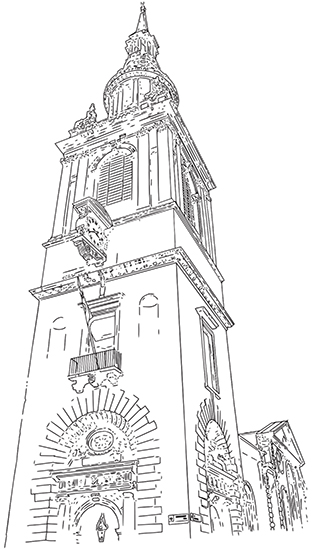

Sir Christopher Wren’s rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral was completed in 1710 during the reign of Queen Anne. To commemorate the achievement a statue of the monarch was erected in front of the cathedral’s western front two years later. That the Francis Bird-sculpted figure’s back was facing the building was something that lampoonists seized upon quickly.

With time, the statue’s stone became weathered. In the late 19thC a decision was taken by the Corporation of the City of London that it should be replaced by a copy. The present one (1886) was carved by Richard Claude Belt, who had a controversial reputation. In 1886 he was convicted of conspiracy to obtain money by false representations. He received a year-long prison sentence with hard labour. The Corporation decided against cutting its losses and instead arranged for materials to be sent into Holloway Prison where the sculptor was serving his time. There, he finished the work. The figure was put in place and duly unveiled to the public. Upon his release he complained that his name was not present on the plinth.

The Bird statue was rescued from a stonemason’s yard. It now resides on the South Coast.

The first St Paul’s Cathedral was commissioned by Ethelbert King of Kent in 604. It was probably a wooden structure. The building was consumed by a fire during the same century. A second cathedral was raised upon the site. In 962 Vikings destroyed it. A conflagration burned down a third one in 1067. The recently victorious Normans used this misfortune as an opportunity to mark their arrival. The stone edifice that they created was larger than the current building is.

In 1663 the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s invited Sir Christopher Wren to survey the cathedral. He recommended that the structure should be demolished and that a new one should be built. His proposal was not acted upon. The Great Fire of 1666 carried the matter.

The plan for the new St Paul’s became a matter for considerable politicking. Wren’s initial design was based upon a Greek cross and was to have been topped by a dome. The Dean and Chapter rejected his proposition. They wanted the old cathedral to be rebuilt and regarded his scheme as being too Roman Catholic in character. For his second design the architect commissioned what became known as the Great Model. This cost £600 to make. The cathedral authorities again regarded his proposal as being too Romanistic.

Wren made a third submission in the form of a drawing. This became known as the Warrant Design. The Dean and Chapter gave their approval to it. The City of London’s livery companies also endorsed it. In 1675 King Charles II sanctioned it. However, the architect does not appear to have built what he had depicted. Instead, for the next 35 years he oversaw the cathedral’s construction without ever setting down on paper his true design for it. To avoid having to make further compromises, he started by laying out all of the ground plan - it was based upon a Latin cross - and then building upwards rather than starting at one end and then working towards the other.

The dome of Wren’s St Paul’s is not a single structure but rather two distinct ones that have up to 60 feet (18.3m) of space separating them from one another. The inner hemisphere, visible from within the cathedral, is made of brick. The outer one is a timber frame that has been covered with lead. Linking them there is a cone-like structure that supports the weight of the lantern that tops the upper, outer skin.

The building was finished in 1710. Wren is reputed to have been the first architect in the history of Christianity who had lived to see the cathedral that he had designed be completed.

Direction: To the north of St Paul’s Cathedral’s western end stands the re-erected Temple Bar. The structure used to stand at the union of Fleet Street and Strand.

In 1889 the stones that had been the Temple Bar were bought by the brewer Sir Henry Meux, who had them re-erected on his country estate at Theobalds, near Cheshunt in Hertfordshire. In 2004 the Bar was re-assembled upon a site to the north of the entrance of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Running eastwards along the northern side of St Paul’s Cathedral is the northern portion of St Paul’s Churchyard.

From the late 15thC onwards booksellers traded in St Paul’s Churchyard. The land was subject to ecclesiastical jurisdiction. This meant that foreigners and non-liverymen could operate there without their activities being hindered by City of London’ officials or the guilds.

During the early 20thC Paternoster Row was the hub of the British publishing industry. The district’s warehouses held many millions of books at any given time. During the Blitz the area was destroyed by aerial bombing. Following the return of peace the publishers moved their business away from the district.

Direction: Walk southwards past the western end of St Paul’s Cathedral. Turn left and skip merrily eastwards along the southern portion of St Paul’s Churchyard. At the cathedral’s southernmost point look southwards. Past Peter’s Hill can be seen the Millennium Bridge and at its far end the Tate Modern gallery.

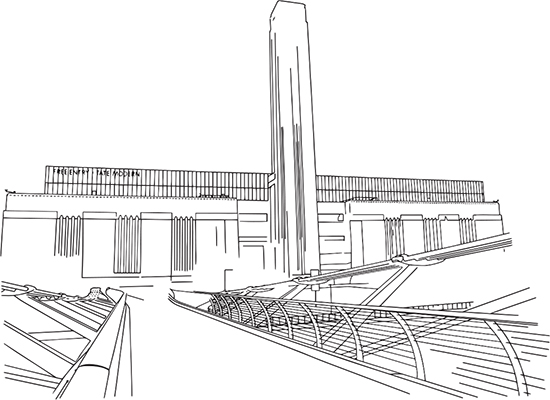

The Tate Trustees concluded that the Tate Gallery should house its international modern and contemporary art works in a separate building. The Sir Giles Gilbert Scott-designed Bankside power station (1963) had been decommissioned in 1981. The idea that the Tate could acquire the former electricity generating facility was first promoted to it by an architectural historian who was concerned about the survival of the structure. Its ground level covered an expanse that was of a similar size to the footprint of the Tate. The prospect that the institution could acquire the site became financially viable because the National Lottery was established. A strand of the latter’s profits had been earmarked to finance projects that would commemorate the then forthcoming millennium.

The Swiss architectural practice of de Meuron & Herzog was awarded the contract to design the building’s conversion. The firm had a reputation for appreciating artists’ needs. A distinctive feature of its plan had been not to subdivide the turbine hall by means of mezzanines and walls but rather to leave it as a single vast exhibition space that could prompt the creation of works that could be displayed in it.

The Tate Modern building was formally opened by Queen Elizabeth in 2000. The monarch has a reputation for not being interested in modern art. She inaugurated the gallery with the words ‘I declare the Tate Modern open’ and then left. (A few months later she opened the British Museum’s Great Court. Upon that occasion she spoke for quarter of an hour about the worth of the museum.)

Direction: Continue eastwards along St Paul’s Churchyard. The road metamorphoses into being Cannon Street. Turn left into New Change. Go northwards. Look at the cathedral from the north-eastern entrance to its grounds. Turn right into Cheapside.

Cheapside means ‘market place’ in Middle English. It was medieval London’s broadest street and hosted the city’s principal market.

Until mid-19thC the street was one of the City of London’s principal retail centres.

Direction: Continue south-east-eastwards. On the right is the northern end of Bread Street.