Cornelia M. Clinch (October 20, 1803–October 25, 1886), the daughter of an established ship chandler in New York, married Alexander Turney Stewart (October 12, 1803–April 10, 1876) in 1825. Their three children all predeceased their father. Born in Ireland, Stewart had emigrated to the United States when he was 16. In his early twenties, Stewart inherited about $5000, purchased Irish laces, and sold them at a small shop in New York City. In 1846 he moved into a new five-story dry-goods store at the corner of Chambers Street and Broadway. Because business prospered, in 1862 he commissioned a second store, which became known as the Uptown Store. Designed by John Kellum (1807–1871), it contained eight floors and was a wonderfully equipped, popular and extremely profitable operation on Broadway between East 9th and 10th Streets. Stewart’s success may have marked the apogee of the influence of the merchant class in the United States before it was superseded by industrialists and bankers.

In the late 1850s the Stewarts purchased, for $225,000, the splendid town house of Dr. Samuel P. Townsend, the largest brownstone in the city, which had been built recently on the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and West 34th Street. Initially, Stewart intended to strip the interior to the floor joists but reconsidered and ordered all vestiges of the original mansion, even the foundation stones, removed. However, his vaunted business efficiency was not evident in the building process. The project, also designed by Kellum, required 500 workers, who labored in fits and starts over a five-year period, and ultimately cost more than $1.5 million. Completed in 1869, the mansion commanded the attention and encouraged the wagging tongues of New Yorkers. Its dimensions, 120′ along 34th Street and 72½′ along Fifth Avenue, were huge for a city house of its day. Despite its mixture of Greek, Renaissance and modern French elements, the Stewarts’ “Marble Palace” was an orderly composition. Compared to its discreet but costly dignity, the William B. Astor II brownstone, directly across 34th Street, now looked decidedly second-class.

Inside, the brick walls of many of the Stewart house’s 55 rooms were finished in Carrara marble or painted panels. The floors of major rooms were covered with either marble or tile resting on brick-arch construction spanning iron girders. The main floor, entered from the wide steps on West 34th Street, led to the principal social rooms: hall, reception, dining, music, drawing and picture gallery. The floor above was also divided into eight rooms with 18′9″ ceilings; the plans of these two floors varied little because of the weight of the brick-and-iron construction.

Beside the Stewart house, the finest brownstones of the city would have looked drab and unrefined on their exteriors, and though they might have been comfortable and even elegant within, they were neither as opulent nor as commanding. The drawing room in particular (no. 3), expressed the grandeur, scale, artistic fashion and cultural sophistication that distinguished this house from its New York contemporaries. Yet some observers argued that the house did not look like a home. According to Harper’s Weekly (August 14, 1869):

The building, with scarcely an alteration in the arrangement of its rooms, could be transformed into a magnificent art-gallery. It almost astonishes us to hear the architect speak of this as a reception room, of that as a breakfast room, and of another as the parlor. The beautiful wardrobe and bath rooms are the only portions of the house which distinctively suggest the idea of a private residence.

After Mrs. Stewart’s death in 1886, the Times asserted that there was no question but that the mansion’s grand staircase, spacious halls and picture gallery suited it ideally for club use. In 1891 it was leased to the Manhattan Club, which occupied the structure until 1899, when the club was unable to meet its costs. The house was demolished early in the first decade of the twentieth century.

The Stewarts and their architect had conceived a unique residence and executed the idea, apparently with little self-doubt. The “Marble Palace” was immediately noticed but not immediately loved. Before it was finished Appleton’s Illustrated Guide claimed, “of all the famous buildings on Fifth Avenue, none will ever be so famous…. Words are absolutely inadequate to describe its beauty and unique grandeur.” The New York Sun praised Stewart for a private act with handsome public results. But architect P. B. Wight, acknowledging the cost, wondered how “any one surrounded by works of art, as was Mr. Stewart, could have had so little understanding of what constituted a work of architecture” (American Architect and Building News, May 6, 1876). Despite such reservations, Jay Cantor, in his thorough account of the Stewart house (Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 10), contended that subsequent New York mansion builders were profoundly affected by its challenge.

New Yorkers were intrigued by the anomaly of two relatively plain people living in this conspicuous, palatial house. A contemporary biographer noted Stewart’s abstemious personal habits and his unwillingness to wear diamond pins, watch chains or glittering rings. Obituaries praised his “thrift” and “plain dealing.” Living in a house ideal for social events, he and his wife shunned society. In his last years only close friends and selected art authorities were invited inside.

When Cornelia M. Stewart died in 1886, the New York Times gave her death front-page coverage, but not because she had been a social, political or intellectual force in the life of the city. She had few friends and spent summers quietly in Saratoga and winters in the “Marble Palace.” The coverage reflected local curiosity about the size of the Stewart fortune, estimated in 1876 to be at least $35 million, and her will. She left $15 million less than she had inherited, the difference being attributed to her gifts to charities and relatives and the transfer of property to Judge Henry Hilton (nos. 78 & 79), her financial adviser and confidant of her husband for 30 years. Of the remaining fortune, approximately half went to Hilton in trust and half to the members of her family.

1. Hall, Cornelia M. Stewart house, 1 West 34th Street, New York, New York; John Kellum, architect, 1864–69; demolished ca. 1901. The main hall ran north-south through the middle of the main part of the house. Visitors were dwarfed by the lofty ceiling, silenced by the ghostly statues and paced by the obtrusive but dry Corinthian columns. Although the sculptures chosen by Stewart were in vogue when the house was completed, most would have been considered old-fashioned by the New York art establishment when Artistic Houses was published. The first pair in this photograph was created by Italian sculptors. On the left was the Water Nymph, by Antonio Tantardini (1829–1879), and on the right was the Fisher Girl by Scipione Tadolini (1822–1892). Behind these, respectively, were Demosthenes by Thomas Crawford (1813?–1857) and Zenobia by Harriet Hosmer (1830–1908), both Americans. Behind Zenobia, was a clock, 14′ high, from the Eugène Cornu factory of Paris. At the end of the hall on the right was one of the scores of copies of Nydia, by Randolph Rogers (1825–1892).

The hall also served as an introduction to the picture gallery beyond. We can see the canvas of Beatrice and Benedict by French artist Hugues Merle (1823–1881).

2. Reception room, Cornelia M. Stewart house. This room linked the hall with the drawing room, which can be seen through the doorway. Sheldon noted the costliness of objects and surfaces not only here but throughout the house: “Money flowed abundantly during the seven [five] years when this white marble palace was building for a merchant prince ….”

The rosewood table in the center was covered with a slab of Mexican onyx. The bronze and gilt panels of the rosewood cabinets in the corners were decorated with figures in relief. Complementing the design of the ceiling was a commissioned Aubusson carpet. Stewart paid an Italian painter more than $15,000 to beautify the walls and ceilings. Here the decorative panels compete with the paintings. On the left of the doorway was a portrait of a lady by G. J. Jacquet (1846–1909); on the right Marguerite, by G. J. Ferrier (1847–1914). Carved casings of Carrara marble framed the doors and windows. Blue silk covered the chairs and sofas and was also used for the hangings.

3. Drawing room, Cornelia M. Stewart house. The left wall contained three enormous windows that faced Fifth Avenue. Between them were two equally impressive mirrors. This sequence of A-B-A-B-A was repeated on the opposite side of the room, where three entrances—from the music room, side hall and reception room—were separated by two cabinets, each 9′ long and 4′ high. The pattern of the carpet was also divided into three bays and reflected the ceiling’s design, painted in encaustic. Reinforcing the axis were gasoliers and tables below. The drawing room was also divided into three parts vertically: the first contained the gilded whitewood furniture covered with pale yellow satin, the second the mirrors, windows, doorways and gold-toned wall panels and the third the cornice and ceiling decoration.

There were no paintings in this room, but sculptures were carefully placed to maintain the insistent balance: First Love, by American-born R. H. Park (1832–after 1890), stood before the central window and was flanked by two $10,000 Sèvres vases. In front of the 34th Street window was Maternal Love by Salvatore Albano (1841–1893).

4. Music room, Cornelia M. Stewart house. Rooms designed solely for music were not common in American domestic architecture in these years, but were included in some of the larger and more pretentious houses. The ideal music room was expected to have a high and coved ceiling, a minimum of draperies to insure satisfactory sound, and a varied decor that was neither too heavy nor too fanciful.

The major pieces of furniture in this room were of rosewood. The table in the center was highlighted at regular intervals on its skirt by bronze reliefs symbolizing the seasons. This room also contained three cabinets, the panels of which were decorated in silver and bronze high reliefs. The frames of the doorways and windows, as well as the mantel (not visible here), were finished in white marble. In general, the color scheme was quiet but not somber. The cream of the Aubusson carpet, the white marble and the light green that covered the darker portions of the walls and ceiling provided an effective background for the heavier colors of the paintings. However, the Stewart house was so extensively decorated that pictures could not be hung well. Furthermore, the metallic rod-and-chain system of support did not blend easily with the marble and faux-marbre walls. The most satisfactory solution to this problem, rarely employed in other interiors of this series, was the curtained niche at the left, a formal and imposing means of displaying a work of art.

Through the doorway can be seen the end of the main hall and the newel post and first steps of the curving marble staircase, called by an anonymous observer the “most beautiful specimen of architecture of that kind” in the United States.

5. Library, Cornelia M. Stewart house. We know surprisingly little about Stewart’s personal life. He apparently enjoyed books and admitted to friends that he read selections from the Aeneid in Latin before work each morning. His collection of books, however, was less impressive and celebrated than his collection of paintings. The highest prices paid for titles at the sale of his library in March 1887 were $1350 for an original edition of Audubon’s Birds of America, issued in four volumes 1827–38, and $252 for a first edition of the Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America by Audubon and Backman. The books were kept in eight black-walnut cases placed around the room, while the larger portfolios were stored in the drawers of the two 10′ tables.

Although her husband had died approximately seven years before this photograph was taken, Mrs. Stewart had probably made few changes in this room. She commissioned the posthumous portrait of Stewart by Thomas Le Clear (1818–1882), on the easel to the right, and placed her own portrait, by Jeannette Loop (1840–1909), opposite it. Above each, like patron saints from a royal past, were portraits of Elizabeth I of England and Alexander II of Russia. Compared to other libraries in this series, the Stewart’s was larger, less intimate and more formal.

6. Mrs. Stewart’s bedroom, Cornelia M. Stewart house. The main bedrooms were on the second floor in addition to the sitting and billiard rooms and the library. Above the library was the principal guest room, known as the “General Grant Room.” Because the floor dimensions and ceiling height of the family rooms on the second floor were identical to those of the social or public rooms below, and because the decorative character of these rooms was coordinated, form certainly did not follow function in the Stewart palace. Specific activities were claimed from generalized spaces largely through the impact of the furniture, which, in this room, does not blend well with the exuberant curves of the gasolier or with the repeated catenaries of the draperies. Without closets, the bedroom was essentially a marble-and-plaster box, a very expensively finished box. After the plaster was laid on the iron furring, four layers of underground paint were applied before the application of the final design.

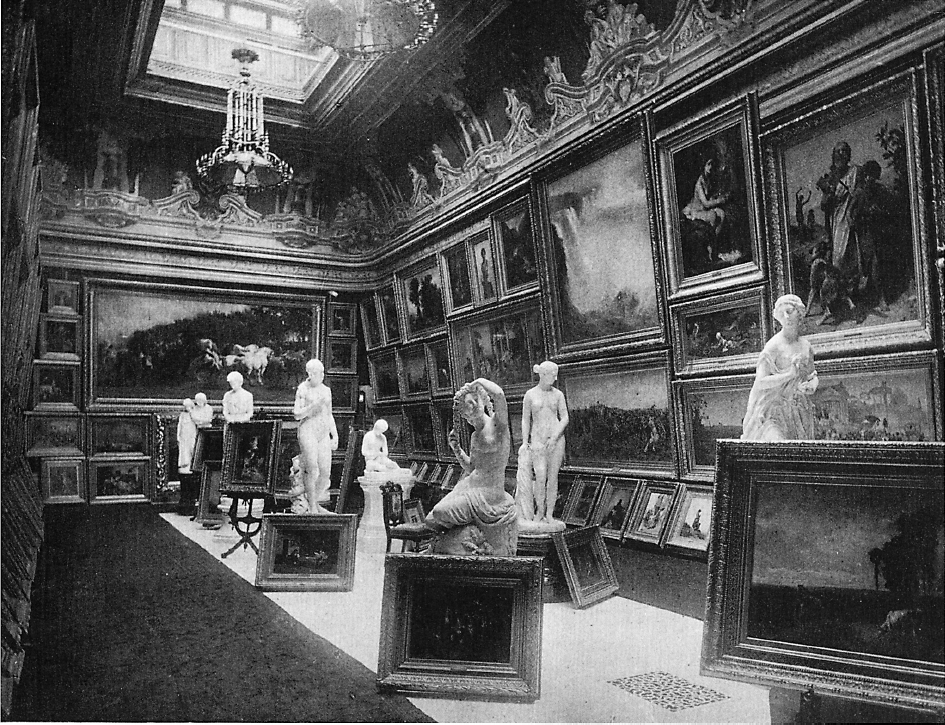

7. Picture gallery, Cornelia M. Stewart house. At the end of the main hall was the entrance to the picture gallery, a windowless space approximately 75′ long, 30′ wide and 50′ high. Built as a block on the north side of the house, it was illuminated during the day by natural light that came through the skylight of glass and iron. Evening viewing was made possible by three gasoliers that hung from the skylight. The gallery’s wall was obscured by the tightly fitted frames, a system that enabled the Stewarts to display about 150 works in this space. When Earl Shinn itemized and discussed the Stewart collection in The Art Treasures of America (ca. 1879–82), he listed 179 paintings and 19 pieces of sculpture.

Because these works of art were collected between 1846 and 1875, they constituted a collection older than most featured in Artistic Houses and did not reflect post-Centennial New York art trends. Nevertheless, it contained paintings by several French artists who were still popular in the United States in the early 1880s: three by Jean-Léon Gérome (1824–1904), three by A. D. Bouguereau, and four by Jean-Louis Meissonier. But the didactic and chromatically conservative character of the Stewart paintings appealed less to later critics. The Art Amateur of November 1879 declared that it was “not exactly the shrine of a poet-painter. You do not go thither to see examples of Delacroix, Descamps, Millet, Corot, Rousseau….”

The sculpture in the immediate foreground is Proserpine by Marshall Wood (d. 1882) and behind it to the left is a seated Flora by Chauncey B. Ives (1810–1894). To the right of Flora were two works by Hiram Powers (1805–1873): Eve Tempted, with apple in hand, and one of the six copies of his Greek Slave of 1843. “Ghosts of connoisseurs of 40 years ago,” was the verdict by a critic of the early 1880s of Stewart’s sculpture collection.

8. Picture gallery, Cornelia M. Stewart house. The Stewarts’ best-known paintings were The Horse Fair (1853) by Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899) and Friedland, 1807, (completed in 1875) by Meissonier. Seventeen feet long, The Horse Fair dominated the west wall of the gallery. The painting’s size, strength and susceptibility to anecdotal embellishments made it one of the most popular works of the period. Meissonier’s interpretation of Napoleon the soldier is in the center of the north wall near the Greek Slave and underneath Niagara from the American Side, an 8′ × 5′ canvas by Frederick Church (1826–1900).

Stewart probably paid between $4 and $5 million for the 1011 objects offered for sale in New York in 1887. $513,750 were bid on the paintings. Friedland, 1807, sold to Henry Hilton for $66,000, brought the highest price. Cornelius Vanderbilt purchased The Horse Fair for $53,000 (the second highest price) and immediately donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That these two paintings, generally considered two of the most important horse paintings of the nineteenth century, were in the United States was cited often by Americans as evidence of the rising sophistication of Yankee buyers.

9. Print gallery, James L. Claghorn house, 222 North 19th Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; architect unknown, late 1850s; demolished 1917. Claghorn (July 5, 1817–August 25, 1884) was one of the more informed collectors in the country from the 1860s until his death. A banker, Claghorn served for 12 years as president of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. After buying more than 300 American paintings and then turning to works by contemporary Europeans, he sold his oils to concentrate on prints, of which he eventually owned between 30,000 and 40,000.

Prints hung on the side wall were exposed to light continuously, but those at the end were hung on sliding panels that would have provided some protection. Rather than offering study space, flat surfaces, such as the Renaissance Revival parlor table at the right, held ceramics from around the world—in this case, a Wedgwood urn and a Satsuma vase.

10. Drawing room, E. Rollins Morse house, 167 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts; Sturgis and Brigham, architects, 1880–81; standing. Morse (October 21, 1845–September 10, 1931) was a banker and investment broker who, in partnership with his brother Charles J., operated a firm at 28 State Street in Boston. He married Marion R. Steedman on May 29, 1873; she died on May 1, 1920. With considerable assets, social standing and social mobility—the couple also lived in New York and Washington—Mrs. Morse became a hostess of renown, one of the great hostesses of Newport, according to Mariana Van Rensselaer. This building still stands as an attached masonry house on Commonwealth Avenue but has been converted to apartments. Stylistically, the exterior is a combination of delicate Federal motifs and heavy pseudo-Romanesque forms. The main entrance is set within a segmental archway and is adjacent to a broad curving bay window that extends through the three main floors of this four-story building. The ground floor is faced with brownstone, the upper floors with red brick and stone trim.

This room was on the second floor, frequently treated as the main level in Back Bay houses. Because of the relatively quiet walls of stamped leather in old gold and the painted panels of the rather high ceiling, divided diagonally by strips of darkened oak, the center of gravity of this room was unusually low. Furthermore, with its spacious dimensions, modest and comfortable furniture and limited bric-a-brac, the room contrasts markedly with a contemporary type of New York interior (nos. 24, 52, 100, 131) in which the living space doubles as an exhibition area. Works of art were exhibited in the Morse drawing room, but they remained subordinate to the character of the space. The painting of the seated woman in evening dress is by B. C. Porter (1845–1908) and a Venetian scene, on the left side of the fireplace, by Félix Ziem (1821–1911). At far left is a frond of the palm tree that stood in the center of the bay window overlooking Commonwealth Avenue.

11. Drawing room, Hollis Hunnewell house, 315 Dartmouth Street, Boston, Massachusetts; Sturgis and Brigham, architects, 1868–70; standing but altered. Hollis Hunnewell (November 16, 1836–June 11, 1884) was the son of dynamic Horatio Hollis Hunnewell (1810–1902) and the father of Hollis Horatio Hunnewell, who was born in 1868. As a child he lived in Boston and in Paris, where his father was involved with the banking house of Welles and Company. Hollis graduated from Harvard in 1858, worked in Paris with his father, and in April 1867 married Louisa Bronson (April 4, 1843–November 10, 1890) of New York City. By December of 1883 he was ill with an unspecified sickness and he died the following summer.

Designed in the late 1860s, the original house was three bays wide, of brick and brownstone and capped by a mansard roof four stories high on one side and three stories high on the other. On December 18, 1876, a fire severely damaged the structure, which was rebuilt in the early 1880s. The family moved into the house during May 1884.

The Hunnewells had collected, during their residence in Paris, European paintings, the largest of which in this room is the Madonna and Child after Giovanni Bellini (ca. 1430–1516), furniture and heraldic plaques, combined them with fine Chinese porcelains and then pushed all of these items in their drawing room to the edges to clear the central space for traffic. The result is a large cocoon of impressive objects from varied times and cultures.

12. Tapestry room, Hollis Hunnewell house. This room is appropriately named for the tapestry that encircles it and determines its character. Remarkably, the scenes depicted on the wall continue around the room, even across the draperies, without interruption. The conspicuous border of the tapestries is continued to the center of each window, where the top and bottom borders are joined by side borders to complete each scene. Because of the exact conformity of the scenes in the tapestry to the height and width of each wall and because of their use in the window drapery, these textiles must have been commissioned expressly for this space. In order to show off these richly decorated surfaces, the number and obtrusiveness of pieces of furniture and other objects have been controlled. The furniture is low and delicate, the carpet fine but relatively subdued, the ceiling painted a solid color and the cornice restrained.

13. Hall, Louis C. Tiffany apartment, 48 East 26th Street, New York, New York; architect unknown, date unknown; demolished. Louis C. Tiffany (February 18, 1848–January 17, 1933) inherited over $13 million in 1902 on the death of his father, Charles L. Tiffany, founder of the well-known jewelry firm, now Tiffany & Co. Instead of joining his father in business, Louis studied painting in the United States and in Europe. In 1879 he and three friends—Samuel Colman (1832–1920), Lockwood De Forest (1850–1932) and Candace Wheeler (1828–1923)—formed Louis C. Tiffany and Company, Associated Artists, a firm dedicated to the revitalization and modernization of interior design. Although this partnership ended four years later, its influence on interiors in the Eastern United States was cited often in art publications of the 1880s. Sheldon included several interiors by Associated Artists in Artistic Houses, among them numbers 17, 18, 52, 67, 68, 108, 139–142 and 198.

Tiffany and his family—his wife, Mary Woodbridge Goddard, whom he married on May 15, 1872, and their three children—moved in 1878 into the top story of the Bella Apartments on East 26th Street. Two years later The Art Journal (vol. 6) featured his redesigned quarters in an article on New York studios. The author, John Moran, warned his readers that “some might think that Mr. Tiffany pushes his decorative ideas to an extreme….” He had combined disparate elements, his “finds,” in tenuous but refreshing relationships, produced an impression of spontaneity without disregarding artistic balance, and articulated wall surfaces in flat patterns freed from Renaissance weight and independent of Renaissance illusionistic space. After the death of Mary in 1884, Tiffany moved to a multifamily, 50-room house at the corner of East 72nd Street and Madison Avenue.

The hall contains numerous unexpected, seemingly incompatible, objects. Visitors, entering from the elevator through the door at the near left, were confronted by a stack of weapons and equipment that partially obstructed the passageway to the right. More weapons, hanging ungracefully at the intersection of the two corridors, directed attention to the crude, heavily gouged pine rafters. This gabled section was painted brown, and the walls, parts of them covered by bronze and bronze studs, a warm India red. In The Art Work of Louis C. Tiffany (1914) by Charles De Kay, there is a reference to a window in the gable area raised by a large wooden wheel and chain. In the 1880s it was not common to incorporate functional equipment, in the manner of the contemporary British architect James Sterling, in the public spaces of a city residence. At the right is another example, a blunt gas jet attached to the wall by its hose. This jet was placed there to cast a flickering light on the stained-glass window behind it. According to Moran, the abstract design of the window was inspired by one created by daubing the residue of Tiffany’s palette knife. This early window is similar to one he installed in the dining room of the George Kemp house (no. 141).

14. Drawing room, Louis C. Tiffany apartment. According to Sheldon, when Tiffany decorated a room in a former style, as he did his “Moorish” drawing room, he did not follow that style closely. “By Moorish decoration the reader is to understand, not a copy of anything that ever has existed or still exists, but only a general feeling for a particular type.” Sheldon also explained: “In this drawing-room, for instance, the Moorish feeling has received a dash of East Indian, and the wall-papers and ceiling-papers are Japanese, but there is a unity that binds everything into an ensemble, and the spirit of that unity is delicacy.” In other words, the original was a catalyst for Tiffany’s imagination.

The buff Japanese ceiling paper contained glittering pieces of mica. The high screen supported by Moorish columns on the east side of the room separated this space from the hall. Its portieres, reflected in the mirror of the divider, were made from Japanese materials. On the other side of the divider the wallpaper was pink. To the left of the fireplace was Tiffany’s 1879 watercolorof his family, In the Fields at Irvington. To attract attention to the relatively small fireplace, he exaggerated the width of the tiled panels to either side, lifted the mantel and filled the opening below with a translucent screen of mica in a spiderweb pattern, and completed the overmantel with three mirrors and shelves.

15. Dining room, Louis C. Tiffany apartment. In this room Tiffany placed circular forms against rectangular sections. The forms are present at all levels, from the tray on the bottom shelf to the fan carving of the eighteenth-century mantel front, the Oriental porcelain charger in the middle of the mantel and the plates to either side, the rounded turkey and pumpkin of the overmantel painting (probably by Tiffany) and, finally, the repeated blue disks of the ceiling. The rectangle of the extremely simple oak table was repeated in the rectangular sections of the walls. The dining room should look more cluttered than it does, considering the number of objects it contains, but because Tiffany concentrates on two geometric shapes, the potential of each to distract is lessened. Furthermore, these forms and surfaces are essentially flat. Even the Japanese wallpaper, with its embroidered borders, and the ceiling paper are space-denying patterns. Tiffany liked wall sections that contrasted in color, design, texture and materials. For example, the fire opening was faced with tile; above it was the carved-oak mantel, the band of dark paper and finally the painting with its strong colors of yellow, red and blue. In stacking these contrasting sections, Tiffany was ignoring the sculptural handling of the fireplace area commonly used by his contemporaries.

16. Library, Louis C. Tiffany apartment. In contrast to most of the dining rooms in this series, which were treated as isolated rooms, Tiffany’s could also be used as an extension of the sitting room or library. The doorway between the two rooms was wide, there were no portieres to obstruct vision or movement (though there probably were sliding doors), and from either space one could see through the leaves of the transom. Yet these two rooms were not similar in character. If the dining room looked nervous and thinly paneled, the library appeared to be busy and stuffed with substantial pieces. The padded wicker chairs were common in such settings, as was the table with multiple shelves for folio volumes. The fireplace was the dominant three-dimensional element. Three decades later, Tiffany was still pleased with the “novel manner” in which he had handled the book shelving around the fireplace. By “novel” he also meant the “irregular balance” he had substituted for the predictable symmetry of fireplace decoration. The wall panels, some left bare but most hand-painted, were also placed without concern for symmetry. These walls seem haphazard and probably too taxing for the tired eye. We should remember that this apartment was remodeled rather than reconstructed. Without denying the planarity of the walls he inherited, Tiffany infused them with an unconventional energy.

17. East Room, The White House, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C.; James Hoban and others, architects, 1792, 1815–17; standing. Because of structural deterioration, new beams, supported by columns at either end, were added to the East Room in 1873. At the same time huge crystal chandeliers were ordered from Germany for this room and for other principal rooms in the house. In 1882 President Chester A. Arthur, having failed to persuade Congress to erect a larger and more elaborate mansion, hired Louis C. Tiffany and Company, Associated Artists, to redecorate the room in keeping with the design standards of the era.

The work was relatively modest, costing a total of $30,000 and requiring only seven weeks to complete; however, Tiffany was able to introduce an aura of splendor and refined taste ideally suited to the temperament of the resident of the White House, for Arthur was a man deeply concerned with appearances and social graces, one who preferred elegance to showy gestures.

In the East Room Tiffany was constrained by the major design features and structural elements already present. The entranceway was the work of Benjamin Latrobe (1764–1820); the frieze, with its Grecian motif, designed by Thomas U. Walter (1804–1887) and the chandeliers, beams, supporting columns, fireplace mantels and overmantel mirrors dated from the 1873 remodeling. Tiffany left these features intact as well as the dominant color scheme of white and gilt. In this 80′ × 40′ space he laid a new Axminster carpet of a sienna color to harmonize with the existing decoration. He applied mosaic pattern to the ceiling in silver leaf, creating shiny surfaces that reflected the carpet below.

Tiffany’s work extended to other public spaces in the White House, notably the Blue Room, Red Room and dining room. He considered his chief contribution a curtain of opalescent glass that separated the downstairs living space from the corridor. In 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt commissioned the firm of McKim, Mead and White to renovate and redecorate the White House completely. When this half-million-dollar project was finished, the work by Tiffany had been erased.

18. Dining room, William T. Lusk house, 47 East 34th Street, New York, New York; architect unknown, 1867–68; demolished. Lusk (May 23, 1838–June 12, 1897) was the author of The Science and Art of Midwifery (1881), which was a standard text for the next two decades. He was also one of the few gynecologists to perform caesarean operations successfully. Ironically, his first wife, Mary Hartwell Chittenden (August 18, 1840–September 13, 1871), whom he married in 1864, died with her child during her fifth delivery. He married Mrs. Matilda Myer Thorn in 1876. Lusk had opened his practice in New York in 1865 and in 1871 joined the faculty of Bellevue Hospital Medical College. In 1894 he became president of the American Gynecological Society.

Lusk was the physician to the Tiffany family during these years, and Tiffany’s daughter married Lusk’s son. The dining room and the parlor of this 34th Street house were decorated by L. C. Tiffany & Associated Artists. The room is a fine example of the firm’s rejection of dark, sculptural effects in favor of planar, reflective surfaces. The woodwork was stained pine, a material most of the owners of these interiors would have considered too cheap and too common. The first register of the room was lined with disciplined right-angled parts—the cupboard, tiled fire front and wood box on the left and the buffet and diminutive doorway to the pantry on the right. Between the woodwork and the bronze frieze, the wall was covered with quiet Japanese paper. On the distant wall this register was dominated by two transoms composed of square panes of diffused amber glass. These transoms distract one from the stubby windows of transparent glass below. Tightly organized and visually charged, this interior was an American counterpart to the energy and impermanence found in the contemporary paintings of Degas and Cézanne in France.

19. Library, Clarence H. Clark house, 4200 Locust Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; architect unknown, late 1850s; demolished 1916. Probably erected in the 1850s and later enlarged, this house was one of the grand mansions of West Philadelphia. The formidable structure was eventually composed of a three-story ashlar block in the center with two-story wings at either side, and a one-and-a-half-story projection from each wing. Horses and carriages swung in from Locust Street along a wide, curving driveway to deposit women and gentlemen before a large and highly ornamented portico. Behind the house was an extensive park open to the public. The site is now occupied by the University City New School.

The library was contained in one of the projections and terminated a vista of more than 125′ across the rooms of the main floor. Spatially distinctive, this room expanded into deep alcoves, one of which is visible at the left, and was covered by the octagonal ceiling approximately 20′ above the floor. This ceiling was divided by oak beams into geometric sections filled with embossed leather. Below the beams was a window frieze of stained glass that included at intervals the words of a Goethe sentiment: “Like a star that maketh not haste, that taketh not rest; be each one fulfilling his God-given hest.” One of Clark’s “God-given” hests was to cover his walls with embossed leather. The art and bric-a-brac in this room were combined without much concern for stylistic or cultural unity. Between a reproduction of the Ghent Altarpiece of 1432 on the left and a miniature copy of the statue of Augustus of Primaporta of 20 B.c. on the right were exquisite ceramics from the Orient and nineteenth-century American and European paintings. The two portraits on the left wall were probably painted by George Munzig (1859–1908) of Boston. The tall volumes on the lower shelf, rarely seen in the libraries included in Artistic Houses, were probably well-bound runs of art or architectural journals to which Clark subscribed.

20. Dining room, Clarence H. Clark house. The son of banker Enoch W. Clark and the father of banker Clarence H., Jr., Clark (April 19, 1833–March 13, 1906) possessed one of Philadelphia’s major fortunes. He was regarded as a leading art collector of Philadelphia and served on the Board of Directors of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 1871 until 1905, from 1892 as vice president. He preferred anecdotal, didactic paintings. Although the Oriental scene on the left, by E. L. Weeks (1849–1903), an American follower of J.-L. Gérome, was a prized picture, it was not well displayed. It was hung too high; overlapping the woodwork was not common. Furthermore, the woodwork and the Victorian mahogany table and chairs were too strong and too shiny for the good of the painting. Even the fireplace and overmantel, with the delicate Chippendale brass andirons, look somewhat frivolous in this ponderous, dark setting.

21. Flemish ballroom, Frederic W. Stevens house, 2 West 57th Street, New York, New York; George Harney, architect, 1875–76; demolished. Few rooms in New York in the early 1880s were as formal and historically correct as this one. Stevens and his first wife, Adele Livingston Sampson, whom he married on October 8, 1862, had the room shipped over from Ghent, Belgium, where it had been used for more than a century. Conscientious about authenticity, they claimed to have recreated the original, with its Gobelin tapestries, carved marble mantel, the wood carvings of the doors, corners and walls, the floor of oak parquetry and the furniture covered with Beauvais tapestries. Though the act was questionable, the result was socially incontestable. By treating the evolution of interior decoration as conservatively as possible, they had at least protected themselves from the risks of short-lived vogues or unrealized blunders.

Stevens (September 19, 1839–January 20, 1928) was one of the blessed people of the nineteenth century, the son of a wealthy New York merchant and the grandson of Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury under Jefferson and Madison. His education—Yale—was proper, his church affilation—Episcopal—was proper, he summered at Newport in a house designed by McKim, Mead and White and actively supported the New York Public Library and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Trained as a lawyer, he became a New York banker. Society-conscious, he maneuvered two of his daughters into marriages with European nobility. One of the few flaws in Stevens’ public image was his divorce from his wife in 1886. He married Alice Seely in December 1904.

22. Drawing room, Frederic W. Stevens house. The character of the ballroom was expressed through its obvious balance and careful coordination, its impression of a delicate space bounded by relatively flat, thin planes and by the discreet placement of finely finished objects and functional parts. By contrast, the drawing room, more representative of expensive New York interior decoration of about 1880, was not ruled by such stringent symmetry. One of the fireplaces was centered against its wall, the other was not. Although the furniture was appropriate for this setting, its colors and shapes and its effect on surrounding space were rather dramatic and varied. The darker walls and ceiling were divided into sections by gilt strips and shallow beams, making these surfaces appear more vigorous and plastic and less precious. Finally, the room presented a moderately helter-skelter appearance. This can be seen in the right foreground where the casual but calculated placement of disparate objects is visible. From her father’s house Mrs. Stevens brought old velour hangings and furniture, covered in deep garnet velvet on a gray satin ground. The shelves of books in a drawing room were unusual for a house that possessed a separate library.

23. Hall, Frederic W. Stevens house. Montgomery Schuyler (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, September 1883) and Mariana Van Rensselaer (Century Magazine, February 1886) praised the exterior of the Stevens house. It was a freestanding structure on the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and West 57th Street, an area in which prominent New Yorkers were building in the early 1880s.

Even in this period of rich interiors, this hall, entered from West 57th Street, was profusely decorated. Stevens claimed that the tapestries in this space, describing the story of Psyche, had been manufactured in Brussels in the late sixteenth century. Additional tapestries were used as portieres or were draped over railings of the floors above. Few surfaces remained quiet; the carved table, metal clock, English mosaic floor, twisted colonnettes, individually designed balusters, stuffed peacock, fluted supports (matching those in the tapestries), the massive urn in the center and double-clustered brass chandelier designed by Cottier & Co. of New York all demanded attention and examination. The profusion of objects and competing surfaces obscured the quality of the oak paneling.

Nevertheless, contemporaries gave the hall high marks. According to Mrs. M. E. W. Sherwood in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, October 1882: “The grand hall … is a picture in itself. This house is thoroughly artistic and in the modern style…. It shows that all the study and talk about high art is not nonsense, but that it means harmony and perfection.”

24. Drawing room, John A. Zerega house, 38 West 48th Street, New York, New York; architect unknown, 1882–83; demolished. Although the Zerega residence was situated near some of the legendary Fifth Avenue mansions of the late nineteenth century, and was by no means a cheap building, it probably would have been placed in the second tier of mansions: buildings that were smaller and had fewer ceremonial rooms, and were often erected on restricted lots that allowed little external expression of luxury and wealth. Mr. Zerega, born about 1826, was a stockbroker who was known at the Exchange as “the Pirate,” possibly because he had been a clipper-ship operator in his father’s shipping business as a youth or because, according to the Times, “he had tender scruples against selling out a customer when his margin became exhausted.” Information about Mrs. Zerega is scant. Both were listed in the Social Register of 1910.

Noteworthy in this drawing room is the clear reliance on furnishings rather than architectural finish to carry its decorative statement. Competing surfaces—the carpet, sofa covering, mantel cloth, blue-and-gold floral paper—animate this space to the point of diminishing returns. Not until the eye reaches the plain frieze of raised gold does the visual cacophony stop. Likewise, the ceiling, articulated with geometrically laid ribbing against a plain background, is treated as a relatively neutral surface. But below, the primary objective was to compose a “pretty” symphony of floral patterns and colors, an objective difficult for us today to understand. The central-heating system in this house enabled the family to open one room to another, as is evident in this photograph. However, the Zeregas, like the majority of owners in this series, treated the rooms of their open plan as separate exhibit spaces rather than emphasizing freedom of movement or spatial linkage.

25. Drawing room, John A. Zerega house. This view of the drawing room proves the popularity of embroidery in city quarters in the early 1880s. At the immediate right, three panels of the piano were covered with embroidered and painted kid. In the right corner of the room was an embroidered screen depicting a woodland nymph, based on a painting by John La Farge (1835–1910). The work that thrilled Sheldon, however, was the artistic hanging of the archway. “This splendid portiere, easily the principal feature of the apartment, was designed by Mr. La Farge, after a pencil-drawing by Mrs. Zerega, and executed by the ladies in Miss Tillinghast’s studio. It is a sunset landscape … casting its flush of evening splendor in silver gleams of sunset on a high ground covered with peonies, in the midst of an environment of exquisite rich browns, olives, and golds, a great feeling of atmosphere, a solid study of varied hues and contrasted textures, a broad and harmonious wealth of chiaro-oscuro, a wise balancing of tones, a finely-harmonized scheme of coloring, and a rare capacity on the part of the artists to see their subject as a whole, so that we may speak of this portiere as an epoch-making work of picturesque embroidery….”

26. Dining room, John A. Zerega house. This room was a one-story extension at the rear of the main portion of the house. Its location meant that it would be near to the kitchen and the servants’ area and could be constructed at a cost lower than that of rooms within the confines of a multistory building. In order to accommodate the long extension tables needed for entertaining, dining rooms in late nineteenth-century residences were often the largest single space in the house, and the solution of a one-story block was an economic way to obtain the necessary dimensions. A projecting block also permitted more light. Here windows were placed in the four short sides of the octagonal plan, producing enough light to require curtains to regulate it. For the clerestory windows above these curtained windows, the Zeregas chose Latin words felicitously suited to dining in the 1880s: Hospitalitas, Amicitia, Familia, and Prosperitas (hospitality, friendship, family and prosperity). The muted glow from these stained-glass panels was especially noticeable at sunset.

The fireplace mantel of mahogany extended almost to the mahogany frieze at the top of the wall. Mahogany was used throughout the room, in the sideboard (not visible) and in the furniture upholstered in stamped leather colored to match the woodwork. The stamped wallpaper was gold, the rug on the floor based on Smyrna patterns.

Mrs. Zerega painted the three canvas panels of the screen in the center of this photograph, proof of the interest of cultured women of this era in the arts.

27. Hall, Robert Goelet house, corner Narragansett and Ochre Point Avenues, Newport, Rhode Island; McKim, Mead and White, architects, 1881–83; standing. Although Goelet (September 29, 1841–April 27, 1889) listed himself as a lawyer, his principal occupation was managing his numerous real-estate holdings. Like many of the New Yorkers included in Sheldon’s anthology, the Goelets—he married Henriette Louise Warren in 1879—lived in grand style with a town house on Fifth Avenue, a fall and winter retreat at Tuxedo Park, New York, this summer house at Newport, a 306′-long steam yacht, the Nahma, and memberships in more than 20 social and civic organizations.

In October 1881 Goelet purchased this prized 7½-acre site on the Newport Cliff Walk for $100,000. By December of that year McKim, Mead and White had finished the plans for one of their finest summer “cottages,” regarded today by historians as a monument of the shingle style. “Southside” was large (150′ × 50′), brick on the ground story and shingled above, and asymmetrically picturesque.

This hall, much less playful than the exterior, especially the ocean facade, is one of the memorable interiors of American resort architecture of the early 1880s. It is exceptionally large (44′ × 30′ and 24′ high), centrally located in the plan and, spatially, the primary link in the traffic movements of the first floor and between the first and second floors. The opening to the left leads to the drawing room, that to the right to the sitting room. Because of its central function in family life, its scale, oak paneling, tapestries that recall hanging banners and the large, simple and strong fire opening, the room is reminiscent of the manor halls of late medieval England. The bamboo lounge and rocker, however, remind us that this is an American summer haven.

28. Hall, Robert Goelet house. This photograph was taken from the entrance to the drawing room visible in number 27. The bracket of the fireplace is at the far left. From this position the space looks more like a living hall. The owners have confidently but nonchalantly thrown together such disparate pieces as the tiger skin on the floor and the Jacobean open armchair against the paneling. Most of the pieces of furniture were easily movable, suggesting that the social occasion rather than the formality of the hall determined where one sat. The main feature of the room from this perspective was the hand-carved canopied bed, which had been transformed into an upholstered retreat. The ferns on the top of the bed and the casually draped cloths on the balustrade humanize a space large enough to be intimidating.

Stanford White’s upper gallery was a brilliant complement to a hall that at ground level was so strong and elegant. Though not incompatible, its tone was different—quicker, lighter, spatially more intriguing.

29. Library, Samuel Colman house, 7 Red Cross Avenue, Newport, Rhode Island; McKim, Mead and White, architects, 1882–83; standing. “Dignified yet rural,” was Mariana Van Rensselaer’s verdict on this relatively modest Newport cottage designed for Samuel Colman (March 4, 1832–March 27, 1920) and his first wife, Anne Dunham. Colman was a popular landscape painter and a founder and first president of the American Society of Painters in Water Colors. He also developed one of the earliest and finest American collections of Oriental prints and pottery. Colman joined Louis C. Tiffany, Candace Wheeler and Lockwood De Forest in 1879 to create Louis C. Tiffany and Company, Associated Artists.

His primary responsibility with Associated Artists was designing fabrics and wall and ceiling papers. The fabric over the mantel reflected his style: a plant or organic motif conventionalized and repeated in an allover, vacuum-abhorring pattern. This field of stylized energy was surrounded by a neutral border, a scheme similar to that of the ceiling, where the framing of the border was inspired by Japanese architecture and the field within—a network of ebony over Japanese silks—was inspired by his visit to Morocco. He also combined Moorish and Oriental references in the fireplace. One reason this interior seems so busy is Colman’s reluctance to permit the surfaces of his walls to be quiet. It is also cluttered by furniture and books that have not been neatly arranged. We see this room not “on display” but as it probably looked during a normal day.

30. Library, Charles H. Joy house, 86 Marlborough Street, Boston, Massachusetts; Sturgis and Brigham, architects, 1873; standing. Numbers 86 and 82 Marlborough Street are paired Ruskin-ian row houses, three stories high with octagonal bays and mansard roofs. An illustration of this library appeared in an early issue of the American Architect and Building News (January 15, 1876). The room measured approximately 17′ by 19′ and was 11′ high. Black walnut was used for the low built-in bookcases, for the panels that reached to narrowly set beams and for the ceiling. In the frieze panels were scenes created by J. Moyr Smith, a British architect Sturgis may have met in London. To relieve the serious, almost heavy-handed treatment of the paneled walls and ceiling, the Joys covered the floor with colorful rugs in lively patterns and the architects finished the fire opening with decorative tiles taken from a convent in Spain.

The statuettes on the mantel were paired figures of Henry IV of France and his wife, Marie de Médicis, owned until a few years earlier by “a noble French family.” Opposite the carved French chest in the middle of the far wall and not visible in this photograph was a rectangular bay illuminated by ten stained-glass windows. The room also contained a portrait of a Joy ancestor, supposedly by John Singleton Copley (1738–1815), and a portrait of Joy’s great-grandfather, possibly in the overmantel, attributed to Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788).

Little is known of Joy (1844–1892). An obituary notice in the Boston Evening Transcript called him the “last of an old and wealthy Boston family,” despite his five children, three boys and two girls, who came from his marriage in 1865 to Marie Luise Mudge. He held memberships in the Somerset Club and the Eastern Yacht Club, and had a summer home in Groton, Massachusetts.

31. Parlor, Ulysses S. Grant house, 3 East 66th Street, New York, New York; architect unknown, date unknown; demolished 1933. After serving two terms as President of the United States (1869–1877), Grant (April 27, 1822–July 23, 1885) toured the world with his wife, the former Julia Dent (January 26, 1826–December 14, 1902). He returned in triumph, but nearly penniless. With an income of approximately $6000 a year, they settled first in Galena, Illinois, and then moved to the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York, where they received special rates. Aware of their limited resources, 20 friends, among them George W. Childs, Hamilton Fish and J. Pierpont Morgan, collected money to enable the couple to purchase a brick home in the city. Mrs. Grant was ecstatic:

It was a much larger and a more expensive house than we had intended (or had the means) to buy, but it was so new and sweet and large that this quite outweighed our more prudential scruples…. And how happy I was all that autumn in ordering the making of my handsome hangings, the opening of my boxes, and the placing of all the souvenirs collected during our long and eventful journey around the world.

The walls and ceiling of the parlor, a room exceptionally simple for a former President, were painted in an unvaried light hue. Likewise, the woodwork of the doorways, mantel and ceiling was restrained. Against these neutral surfaces, the Grants arranged many of the objects they had received on their trip, among them the two teakwood cabinets in the corners, the porcelains near the fireplace and the embroidered screen depicting a cock and a hen that rests against the wall below a version of Sheridan Twenty Miles Away by T. Buchanan Read (1822–1872). In addition to these gifts from Japan, the Mikado personally gave them the pair of large silver vases on the mantel. Mrs. Grant purchased the rug in India.

32. Library, Ulysses S. Grant house. In 1884, a private banking firm in which Grant had invested failed, leaving him with immediate debts. To meet these, he began writing his memoirs in this second-story library. He completed them four days before he died of throat cancer in an Adirondack cottage.

The bulk of his book collection was given to him by the citizens of Boston. This room also contained gifts—canes, swords, medals, decorative boxes—from European cities. The plain walls and simply decorated ceilings, plus the absence of wainscoting in the rooms of the Grant house, contribute to settings that were restrained for a posh New York town house of the day. Mrs. Grant sold the house for $130,000 in 1894. The house had been used as a four-story tenement before it was razed in September 1933.