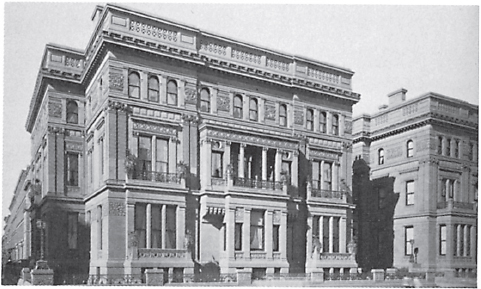

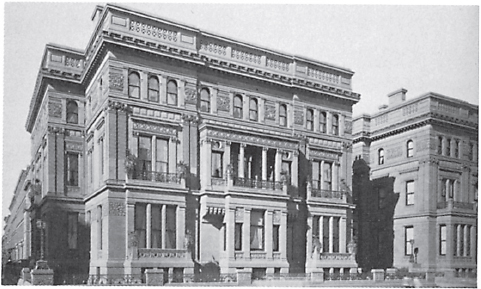

The Fifth Avenue facade.

Not since the building of Stewart’s “Marble Palace” in the late 1860s had New Yorkers paid as much attention to a house as they did to this one. After all, one of the richest men, if not the richest man, in the world had decided he wanted a house that reflected his worth. In 1877 William H. Vanderbilt (May 8, 1821–December 8, 1885) inherited about $90 million from his father Cornelius, became president of the New York Central Railroad immediately and by 1883 had won control of the Chicago and Northwestern, the Nickel Plate Road and other systems that extended his network westward to St. Louis and Minne-apolis-St. Paul. At the time of his death his fortune had increased to an estimated $200 million, a figure so incomprehensible that one Wall Streeter in 1884 translated its value into more meaningful terms: On interest and dividends alone Vanderbilt earned “$28,000 a day, $1200 an hour, and $ 19.75 a minute.” New York newspapers realized they had good copy—the construction and decoration of a huge mansion for a man of inordinate means who wanted nothing but the best—and they watched its rise and subsequent alterations closely.

Mrs. Vanderbilt, Maria Louisa Kissam (d. 1896), daughter of a Brooklyn minister, did not want to leave their comfortable home at 450 Fifth Avenue. Furthermore, most of their eight children were no longer living with them. She urged her husband to add a wing to the old house to provide the space he needed for his growing collection of paintings. But in 1879 Vanderbilt paid $700,000 for property that stretched from West 51st Street to West 52nd Street on Fifth Avenue. Then, with adequate land in a currently fashionable location, he asked the decorating firm of Herter Brothers to design and furnish the house.

Charles B. Atwood (1849–1895), an architect working for Herter Brothers, was probably the designer of the Vanderbilt house. However, the firm wanted the credit and wrote to the American Architect and Building News (May 2, 1885) claiming responsibility and characterizing Atwood as a mere employee. Historians, however, have had difficulty attributing this house to a decorating firm. To complicate the matter, the building permit was taken out in August 1879 in the names of Atwood and John B. Snook (1815–1907). Snook was a contractor hired by Vanderbilt to be general superintendent of the construction process. He added to the confusion by introducing himself as the architect when showing members of the press through the partially completed building.

The house was completed in two and a half years, a short period considering the profuse and costly interior decorations, and the Vanderbilts moved in at the end of January 1882. The photograph on this page shows their section at 640 Fifth Avenue; at the right is a portion of the northern half of the double house containing the residences for two of their daughters, Margaret Louisa (Mrs. Elliot F. Shepard) and Emily (Mrs. William D. Sloane). To speed construction, the marble initially planned for the exterior was rejected in favor of sandstone from Connecticut. From the street the house looked like a three-story dwelling but actually contained four interior floors. The first two floors were 16½′ high and the third 15′ high while the width was approximately 80′ and the depth 115′. Vanderbilt wanted a mansion large enough to express his position but also one that was removed from the common life of the sidewalk and street. Here his objectives clashed. Because the house was too large for its site, only a symbolic moat of grass and a sandstone wall provided defensible space. Newspapers hinted that Vanderbilt would purchase and then destroy the block-long building directly opposite, a Roman Catholic orphanage, in order to obtain a garden forecourt.

The Fifth Avenue facade.

As an architectural statement, the Fifth Avenue facade was not memorable. It contained the beginnings of messages that were not finished. Were the owners and designers short on courage? Were they too self-conscious? The plastic promises were ironed flat, the strength of supports compromised by meticulous enunciation, the bands of decoration hygienically isolated. Inspired by the rationalized classicism of earlier French architects, the design was restrained and dignified but lacked a topic sentence.

Architectural critics of the day were not pleased with the results. “If these Vanderbilt houses are the result of intrusting architectural design to decorators, it is hoped the experiment may not be repeated,” was an expected response from the American Architect and Building News (May 21, 1881), a journal that called repeatedly for a stronger profession. Clarence Cook (North American Review, September 1882) called the twin houses a “gigantic knee-hole table.” Montgomery Schuyler (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, September 1883) thought its decoration unrelated to its structure, and Mariana Van Rensselaer (The Century, February 1886) agreed with Schuyler but added that without their carved bands the two would look like “brown-stone packing-boxes.” Initial reactions to the interior were quite different. Stunned by the magnificence of the rooms of No. 640, critics expressed their amazement rather than their opinions.

During the last year of work on the interior, Vanderbilt visited Herter Brothers almost every day. He was an ideal customer—enthusiastic, generous, trusting. He made no contracts with them; they simply carried out the work and sent him the bills. To celebrate the completion of the interior, he invited 2000 friends to a reception on March 7, 1882. “Nothing could equal its magnificence in a decorative sense,” reported the Times. Announced as a house, it became New York’s newest and most discussed museum, its contents familiar to a public unable to visit it.

Vanderbilt died there 47 months after he moved in. He willed it to his wife, who died in 1896, and through her to successive Vanderbilt males. It was occupied until 1944 and demolished in 1947 to make room for the Crowell-Collier Publishing Co. The northern half of the block was razed in 1927.

114. Hall, William H. Vanderbilt house, 640 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York; Charles B. Atwood and John B. Snook, architects, 1879–82; demolished 1947. The main entrance led into a vestibule that linked the two halves of the building. At the south end of this space was an inner vestibule, roughly 12′ square, through which one reached the main hall with its superimposed galleries. In this photograph the entrance to the picture gallery on the west is directly ahead, the stairs on the north side are to the right, the door to the dining room on West 51st Street to the left and the opening to the drawing room overlooking Fifth Avenue behind the photographer. With its opulent, eclectic furnishings, this hall was more demonstrative than inviting. It contained a seventeenth-century Lille tapestry, a German bronze of a female falconer, a Japanese sculpture of a sea god and a Chinese screen. The boxy chairs were carved from English oak. Turkish rugs covered the hardwood parquetry, and the walls were divided into a high oak wainscoting and a Celtic frieze inlaid with small panels of marble. Twelve piers of dark red African marble with bronze capitals supported the gallery on this level.

115. Hall, William H. Vanderbilt house. A bas-relief frieze of festoons separated by female masks, interrupted near the corners by double cupids, completed the decoration of the first level. In a matching register a floor higher were reclining figures, symbolizing the seasons, painted by an unidentified French artist. Six tapestries executed in 1624 at Fontainebleau covered the wall of this level. This court rose through four stories and was illuminated primarily by nine stained-glass windows in the roof by day and at night by the sconces attached to the piers of the second level.

116. Drawing room, William H. Vanderbilt house. A sumptuously illustrated four-volume study entitled Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection, by Earl Shinn [Edward Strahan], was published in 1883–84. It was paid for by William H. and probably written with the unacknowledged assistance of Samuel Avery, his art adviser. Historians consider this publication the best record of any millionaire’s house erected in this period. Vanderbilt undoubtedly thought such an achievement should be documented for contemporaries and posterity, and he may have wanted immediate confirmation in print that he was not just a successful businessman but also a friend, if not a student, of art.

In 1911 Gustavus Myers (History of the Great American Fortunes) ridiculed Vanderbilt: “With the expenditure of a few hundred thousand dollars he instantly transformed himself from a heavy witted, uncultured money hoarder into the character of a surpassing ‘judge and patron of art.’” Today, we may conclude that Vanderbilt was self-indulgent and not well informed about art, and while some contemporaries in 1883 would have agreed, a large majority would also have regarded his house as a gift to his city, and its contents as proof and promise of national artistic growth. Paradoxically, this private museum was promoted as evidence of cultural progress about which the public, banned from its doors, could feel proud.

Overlooking Fifth Avenue, the drawing room (31′ × 25′) was located between the library on the north and the Japanese parlor, seen through the parted portieres, on the south. Herter Brothers lavished such attention on this room that even Sheldon sounded mildly critical: “almost every surface is covered, one might say weighted, with ornament….” Within the coved ceiling Pierre-Victor Galland of Paris painted on canvas a procession of knights, ladies and their entourage bringing in the first grapes. Below, the surfaces sparkled. Light was reflected from the mother-of-pearl butterflies and cut crystal sewn on the red velvet walls, from the beveled mirrors in each corner and from the stained-glass vases containing the gas jets. There were additional gas jets in each corner, shielded by a silver figure of a young woman. Mother-of-pearl was everywhere—in the frieze, on the backs of chairs, on the cabinets and casings of doors and windows. The central table, by R. M. Lancelot, was inlaid with gold in addition to mother-of-pearl. On top of this table was an ivory statue encased in glass, Fortune by A. Moreau-Vauthier (1831–1893). The carpet was woven in Europe.

117. Dining room, William H. Vanderbilt house. Located to the west of the Japanese parlor, the dining room (37′ × 28′) was unlike the glittering drawing room. Here the expressive element—the dark stained English oak—was seen in the arched ribs of the ceiling, the wainscoting (12′ high) and the heavy cabinets and shelves surrounding the room. Carved from the same wood were the chairs, which were covered with a dull red stamped leather, a color that suggested age and decorum and matched the hue of the velvet hangings. Solid, rich and Renaissance, this room, more than the drawing room, was closer to Vanderbilt’s self-image, once expressed in a startling phrase, “We are plain, quiet, unostentatious people….” Counteracting the heaviness of the woodwork were the red figures, white, gray and brown horses and the pale blue sky of the scenes painted by E. V. Luminais (1822–1896) of Paris at either end of the dining room and in the central panel of the ceiling.

118. Japanese parlor, William H. Vanderbilt house. According to Sheldon, whose criticism was compromised by his relentlessly positive verdicts, this parlor was “in perfect harmony with the surrounding rooms.” This judgment makes no sense because the Japanese parlor was distinctly and intentionally different. Here Vanderbilt was simply putting on the style—and simultaneously fearing a vacuum—to convince diners on their way back to the drawing room that if he was familiar with the Renaissance he was also aware of the Far East. Sheldon took pains to point out that its setting was invented, not copied. The split bamboo nailed to the plastered ceiling was natural in color, the rafters were lacquered red and the dark red of the wall brocade was fronted by the blues, browns and yellows of the porcelains.

119. Picture gallery, William H. Vanderbilt house. According to a catalog of 1884, Vanderbilt’s collection consisted of 207 oils and watercolors, the majority of which were French. Only two were American. Art historians and critics have been hard on Vanderbilt, depicting him as an aesthetic dunderhead who, with little knowledge and even less feeling, sent Samuel P. Avery to Europe with a fistful of dollars to assemble a collection simply because owning art had become fashionable. Avery denied this in print.

Vanderbilt did rely heavily on his adviser and gave Avery authority to act in his behalf. However, to argue that he was incapable of being moved by art is insulting. Because subject matter was important to him—more important than style—he liked paintings with clear themes, clearly presented. At the left of the archway connecting the gallery and the main hall are two examples of subject matter he enjoyed, the animal picture (After the Chase by Edwin Landseer, 1802–1873) and below it the North African or Turkish scene (Gérome’s Sword Dance, purchased in London in 1880).

The picture gallery (32′ × 48′ and at least 30′ high) was directly west of the hall. A gigantic rug hid the fine parquetry floor. When the Vanderbilts needed a ballroom, the rug and furniture were removed. When the doors between the hall court and the musicians’ loft above the archway were opened, music could be heard throughout the house. The pictures were hung above the ebonized oak paneling and against dull red tapestry. Mahogany was used for the architectural and sculptural highlights and in the ceiling. A skylight containing opalescent and tinted glass illuminated the space during the day. At night, the gallery was lighted by 169 gas jets attached to pipes that crossed it and by naked light bulbs projecting from the walls at the base of the second level. In addition to the musicians’ loft, there were balconies on the north and the south that opened to the halls of the second floor.

120. Picture gallery, William H. Vanderbilt house. William H. also liked sentimental genre, exemplified by Munkacsy’s Two Families on the left above the wainscoting in this photograph. Another favorite category was military paintings, specifically, the depictions of French heroism in the recent Franco-Prussian War. On the huge easel near the center of the left wall was the largest painting in the gallery, The Defense of Bourget, which Alphonse De Neuville (1836–1885) painted in 1878 to honor those who had gallantly defended the village of Bourget against a division of Prussian troops.

In these years when private collection rivaled public museums in quality of material, effectiveness of display and even in documentation—the Metropolitan Museum in New York had published nothing comparable to Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection—collectors frequently set aside times for artists and the interested public to study their holdings. Initially, Vanderbilt followed this practice. By cards of invitation art lovers were admitted at a special entrance on 51st Street on Thursdays from 11:00 A.M. until 4:00 P.M. A year after Vanderbilt moved in he concluded the gallery was inadequate to display his growing collection and commissioned Snook to make major changes that created a vista of almost 140′ from the windows of the drawing room through hall and gallery to the walls of a new, glassed-in garden. On December 20, 1883 Vanderbilt invited 3000 men from the worlds of business and art to inspect the galleries and tour the house. They wandered at will, looked at books, handled costly bric-a-brac and even trimmed some plants as souvenirs. In 1884 Vanderbilt discontinued the Thursday openings.

121. Library, William H. Vanderbilt house. The library was the same size as the Japanese parlor. The most conspicuous feature of this relatively intimate space (17′ × 26′) was its ceiling of small beveled mirrors set in molded plaster. Mahogany and rosewood were the principal woods, the latter visible on the jambs, inlaid with mother-of-pearl and bronze, of the opening directly ahead. The room contained several prized objects. On the left the large painting, done on order by Gérome in 1878, celebrates The Reception of the Great Condé by Louis XIVon the grand staircase of Versailles in 1674. Below this painting is a vase, Science, attributed to M. L. E. Solon (1835–1913) and to its right a fan said to have been owned by Marie-Antoinette. The inlaid rosewood table, decorated with a globe surrounded by stars, was attributed to Charles Goutzwiller (1810–1900).

122. Stairs, William H. Vanderbilt house. This photograph of the main stairway was taken from the first landing. Like most of the spaces on the first level, this section of the stairs was overdecorated. The newel post with its bronze figure of the slave girl illuminating the way, designed by Tony Noel (1845–1909) and cast by Ferdinand Barbe-dienne in 1881, cost a reported $2000. English oak was used for the stairs, paneling and soffit. Between the hand-carved posts of the railing were open panels of bronze strapwork. Red plush cushioned the top of the railing. Amid such surroundings, the picture at the bottom, Dance in a Roman Tavern by Francesco Vinea (1846–1902), depicting dancers and barnyard fowl in a crude interior, was a curious choice. On this landing was one of John La Farge’s most important stained-glass windows, which allegorized in three lights the ships and railroads that had secured the Vanderbilt fortune. A floor above was an equally large window, Hospitality.

Solidly constructed, the Vanderbilt house rested on bedrock and was supported by exterior walls that varied in thickness from 36″ to 8″ and by solid-brick interior walls that were a minimum of 16″ thick. Instead of conventional wood laths, these interior walls were faced with iron wire to which the finished surface was applied or attached. To support such a heavy structure, the designers called for iron columns and beams with brick-arch construction between the beams to insure against fire.

123. Mr. Vanderbilt’s bedroom, William H. Vanderbilt house. The Vanderbilts found repose in the private quarters of the family on the second floor, where he enjoyed his library rocking chair and she could relax in her boudoir. His bedroom was located in the southeast corner of the house near the library. Its walls were decorated with golden-yellow tapestry paper and pale blue draperies, and its ceiling was stenciled with tiny cupids. This room was connected to a dressing room paneled 8′ high with glass tiles and containing a tub and basin of silver set in frames of mahogany.

124. Mrs. Vanderbilt’s boudoir, William H. Vanderbilt house. Searching through the rooms of the Vanderbilt house for signs of human habitation, a writer for the Times wondered if clothes were ever mended there or whether in the midst of such splendors William H. ever needed a button sewn on. In effect, this writer was asking if mere mortals could function in such a rarified domestic environment. In contrast to the main-floor rooms, the boudoir contained clues to the private life of Mrs. Vanderbilt. On the shelf under the foreground table is her sewing basket and above are recently examined books, one of them containing a slip of paper to mark the place. On the rear table is an envelope that has escaped the tidying process that inevitably preceded these photographs.

Compared to the other rooms of the house we have seen, this one was more inviting and also more flexibly arranged. Despite its high ceiling and relatively tall overmantel, its center of gravity was also lower. The boudoir’s most distinctive fixed feature was the mantel hood, carved below and painted above. The frieze, probably designed by Christian Herter (1840–1883) of the New York firm of Herter Brothers, described a Triumph of Cupid in which a maiden, a soldier and even a monk bring gifts. Another mural, depicting cupids singing and dancing, can be seen in the oblong panel of the ceiling. Against the far wall was a cabinet of ebony inlaid with ivory. Among the choice smaller objects, concentrated above the fire opening, was a mantel clock and flanking vases attributed to M. L. E. Solon. The portieres were made of light blue silk; the carpet was predominantly of gold and blue.

125. Hall, George F. Baker house, 258 Madison Avenue, New York, New York; architect unknown, 1880–81; demolished. Today corporations rather than powerful individuals influence the course of American capitalism. This was less true at the end of the nineteenth century and during the years before World War I. George F. Baker (March 27, 1840–May 2, 1931), the “Dean of Wall Street,” “the last of the old guard in the world of American finance” and, at his death, probably the wealthiest person in the United States after Henry Ford and J. D. Rockefeller, once admitted his enormous power before a Congressional committee investigating the Money Trust in 1913. The financial power of the country, he testified, was under his control and that of J. P. Morgan and associates to such a degree that “no great enterprise could be carried forward successfully unless it had their confidence.”

From his base at the First National Bank of New York, he became, at the height of his power, director of 43 corporations and companies. Estimates of his fortune ranged up to half a billion dollars. Yet his home on Madison Avenue, where he lived with his wife, Florence Tucker Baker, whom he married on November 18, 1869, his son and two daughters, was surprisingly modest. On the other hand, the Bakers also owned houses at Tuxedo Park and on Long Island. In 1917 he moved uptown to the corner of East 93rd Street and Park Avenue, and in his later years he spent more time at his retreat on Jekyll Island, Georgia.

The Bakers moved to this address in 1881. Their hall, one of the least cluttered of this series, was, like his reported public style, functional and unpretentious, but not ordinary. The walls of the hall were divided into two parts, a high wainscoting of American oak below and a brocade of jute above. The landing was faced by a screen of spindles and leaded crown glass. Through the door at the right can be seen the mantel of the music room, which connected the dining room at the rear of the house with the drawing room in front.

126. Dining room, George F. Baker house. Sheldon responded positively to the modesty of the Baker dining room:

No guest can sit at its generous board unmoved by the pleasantness of the deep and significant message of the artistic surroundings. A wainscot of antique oak, about ten feet high, extends around the room, terminating at the top in a series of pretty cabinets of the same material, behind whose glass doors appear porcelains and earthenware of excellent pedigree and color…. The ceiling, of paneled antique oak, is connected with the walls by a deep and beautiful frieze of painted canvas, and it is difficult to say which elicits the more admiration, the unconventional interpretative design of leaf and fruit ornamentation, or the bold and decisive touches that have wrought the subdued beauty of tones…. The concord of the various decorations in these rooms does, indeed, constitute an exquisite harmony, but the dexterity of the painter’s brush shines with peculiar effulgence.

127. Drawing room, 55th Street, New York, New York. This was the final plate of volume II of Artistic Houses. No additional information accompanied the photograph.

128. Dining room, Jacob Ruppert house, 1451 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York; William Schickel, architect, 1881–83; demolished. Jacob Ruppert (March 4, 1842–May 25, 1915) was one of the wealthier individuals featured in this publication. Upon his death he left an estate valued at $20 million in trust to his widow, the former Anna Gillig, whom he had married in 1864. Ruppert, a brewer, learned the trade from his father, who came to America from Bavaria in the early 1830s. With profits from the brewery, which he established in 1867 on Third Avenue, Jacob formed a successful real-estate company. A patron of the arts and especially of music, Ruppert owned the Central Opera House in New York. He also raised trotters on his estate near Poughkeepsie.

This house was large (50′ × 100′) and freestanding and cost $90,000. The dining room was richly paneled in antique oak by Schickel and Herter Brothers. Its ceiling was finished in elaborately paneled antique oak and supported at the edges by broad wall brackets. At left, the fireplace was recessed within a broad opening and flanked by built-in seats. The small musicians’ gallery above, with a railing carved from solid oak, was supported at either side by atlantes in the form of satyrs. The walls were covered by a heavily embossed leather paper with designs of grapes and leaves accented in gold against a dull-red background. Along the top of the wall was a frieze showing a Bacchanalian procession of children, leopards and other creatures. This room had a heavy, intricate, Germanic character reflecting Ruppert’s background and social style.

129. Drawing room, Jacob Ruppert house. In its light tones and relatively subdued decoration, this room contrasted sharply with the character of the dining room and hallway. Like the dining room, it featured a frieze, depicting children involved in various sports, painted on canvas with a gold background. The room had a modified Louis XVI treatment with woodwork that was painted ivory with trim accented in gold leaf. A soft red amplified the papier-mâché ornaments of the wainscoting. Divided into square patterns with intricately painted fresco work, the ceiling received the most elaborate handling. The furniture, graceful and delicate in form, was made of enameled wood. The numerous lights of the bronze chandelier would be reflected by the pier mirror above the mantel.

130. Hall, O. D. Munn house, Mountain Avenue, Llewellyn Park, West Orange, New Jersey; Alexander Jackson Davis, architect, 1858–61; standing but altered. This residence was one of three owned by Orson Desaix Munn (June 11, 1824–February 28, 1907) and his wife, the former Julia Augusta Allen (d. October 26, 1894), whom he married in 1849. Their Manhattan residence was located on East 22nd Street, and their large farm was not far from this Llewellyn Park retreat. This was one of a number of fine houses built in Llewellyn Park, a private community for which the celebrated Romantic architect A. J. Davis laid out the picturesque grounds and designed the impressive gatehouse. Many of the residences survive today in what continues as a well-maintained, exclusive residential community. Called the “Terraces” today, the house was designed for stone by Davis but executed in wood. The Munns purchased the Italianate villa in 1869 and commissioned Lamb and Rich to enlarge it in the early 1880s.

At the age of 22 Munn, with Alfred E. Beach, purchased the Scientific American. In addition to publishing this increasingly influential journal, Munn and Company also worked with inventors to obtain patents and to market new inventions.

The walls and ceiling of this hall were paneled in quarter-sawn oak that had been specially treated to give an aged appearance. Above the wainscoting and carved-oak furniture the walls were covered in leather in intricate patterns. This hall is an eclectic space, combining medieval features, such as the wrought-iron lanterns, with Moorish features, such as the stairway screens with their carved diagonal baluster work. The inner hallway was illuminated by stained-glass windows, making it appear somewhat dark, probably to create a contrast with the spacious, airy living hall, which took advantage of the fine vistas Llewellyn Park afforded.

131. Drawing room, William A. Hammond house, 27 West 54th Street, New York, New York; architect unknown, 1873; demolished. The Art Amateur, commenting on Dr. Hammond’s house in June 1879, concluded that “the doctor uses his own ideas and selects his designs, and himself gives instructions to the artisans he employs.” Sheldon also saw a connection between Hammond’s strong personality and cultural breadth and the individualistic manner in which the house was decorated.

Hammond (August 28, 1828–January 5, 1900) was a remarkable person. At 21 he graduated from the medical school of the City University of New York. During the Civil War he served as Surgeon General of the Army but was court-martialed and dismissed from service for criticizing superiors, an act nullified by Congress in 1878. He held several professorships at medical schools in New York City, founded or edited five journals of medicine, authored 280 articles, published 30 books and wrote seven novels. His library of more than 1300 items contained early editions of Ariosto, Boccaccio and Dante. He married Helen Nisbet on July 4, 1849 and Esther Chapin in 1886. Two of his five children from the first marriage survived him, and one of them, Clara, became the Marchioness of Lanza.

Mrs. M. E. W. Sherwood (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, October 1882) regarded these rooms as possibly the first “artistic interiors in New York.” In retrospect, they are good examples of the personalized interiors that appeared between the proper settings of the pre-Centennial period and the self-consciously refined rooms of the later 1880s. In reflecting the American discovery of both Western and Eastern styles and objects, they verify that this new internationalization of taste welcomed simultaneously the Gobelin tapestry, the Caterina Cornaro chests, the Japanese cups and the Spanish faience.

Hammond hired Engel and Reynolds to paint the Celtic cross pattern of turquoise blue on the ceiling of the drawing room and to reproduce on the frieze scenes from the Bayeux Tapestry. The walls were covered with raw silk; below the wainscoting was satinwood inlaid with ebony. Most of the furniture was also of ebony. Unfortunately, the wainscoting was obscured by cabinets and tables, and the walls were weighted with Persian, Moorish, Egyptian, Chinese and Japanese plaques. In the center of the room was a small table on which was a cloisonné chessboard, and directly behind it in the corner stood a miniature version of the Medici Venus. Natural light for this dark room came from stained-glass windows that portrayed two Saxon princesses. To the next generation, this unabashedly worldwide eclecticism looked naive; to Mrs. Sherwood, it represented a learned and courageous step “which will be difficult for artists to surpass for some time to come.”

132. Japanese bedroom, William A. Hammond house. Clay Lancaster (The Japanese Influence in America) is probably correct in claiming that this bedroom, redone somewhat inconsistently to look Japanese, was not original with the house. Nevertheless, it was one of the earliest examples of Japanese influence in American interior design. The Art Amateur (June 1879) described it enthusiastically:

The ceiling is frescoed in bold work of black and gold of unsymmetrical design. The walls are paneled with Japanese painted stuffs framed in gilt bamboo, and the frieze is a continuous band of brilliant figures on paper crêpe. Over the doors, and in the spaces where the tint of wall is flat, fans of brilliant colors have been tastefully displayed. A table in blue and white, and red lacquer saucers inserted in the dull black wood of the furniture, help the effect; while on the mantel, formed like a lacquer cabinet, is a clock made out of an exquisite Chinese lantern in blue and white.

Though Japanese in materials, the room was not Japanese in feeling or function. Did the Japanese shade their gas jets with parasols? Hammond has collected and exhibited Oriental creativity but has disregarded, probably intentionally, the restraint and coolness of the typical Japanese room.

133. Bedroom, William A. Hammond house. The pictorial friezes, ceilings of flat surfaces and relatively quiet wall decoration, particularly in the Japanese bedroom and this room in which Mr. Hammond slept, implied that the rooms of this house were bounded by thin panels incapable of serious support. In this bedroom the responsibility for structural reassurance has been transferred from the walls and ceiling, where it was often expressed in the early 1880s, to the fireplace of oak articulated with Gothic ribbing. Similar ribbing appeared on the dressing table at the far left, behind the leather dressing screen, and in an 8′ × 10′ cabinet, also of oak, directly opposite. Near the corner was a Spanish washstand, no longer used, with a storage cabinet for shaving equipment above. The debate over the advisability of movable washstands or fixed stands with running water was still alive around 1880, but here running water was probably available nearby.

Compared to the fireplace and solid pieces of furniture, the finely detailed brass bed looked delicate, if not flimsy, and insufficient for the task of supporting the 6′2″, 250-pound Hammond. The fabrics of the framework of the canopy have been removed; perhaps they had never been fitted. The right side of this photograph is unusually bare, even for a bedroom. Several small fine rugs have been placed over the plain carpet. The fire opening had a brass-turned fender flanked by two Chinese porcelain vases. Divided into two parts, the wall was composed of heavy composition paper stamped and painted in India-red impasto below and a dark band of raw silk above. Scenes from medieval life were displayed in the frieze. The simple ceiling in black, crimson and gold may have been unfinished when the photograph was taken.

134. Hall, Herman O. Armour house, Fifth Avenue and East 67th Street, New York, New York; Lamb and Rich, architects, 1882–83; demolished. Born near Syracuse, N.Y., Armour (March 2, 1837–September 7, 1901) initially settled in Chicago, where he worked as a grain-commission merchant. In 1865 he went to New York City as the Eastern representative of Plankington, Armour and Co. In 1870 he became a partner in Armour and Co. and was its vice president at the time of his death. On February 4, 1887, at the age of 50, he surprised his friends by quietly marrying Jane P. Livingston of New York.

The hallway in this house was one of the more peculiar illustrated in Artistic Houses. Despite the fine materials—white mahogany used in the front door (seen at the far left), the wainscoting, the band that continues the horizontal lines of the balcony, and the strongly beamed ceiling, and despite the skilled workmanship evident in the woodwork of the balcony, the stained glass above and the Lincrusta Walton wall surfaces—the hallway looked pinched, dark and uninviting. (Lincrusta was an imitation leather derived from solidified linseed oil, introduced by Frederick Walton in 1877.) The two chairs and the plant, obviously included to make this entranceway more attractive, only obstruct a route intended primarily for traffic. The fireplace was probably never used, but its polished reliefs were seen as soon as a visitor crossed the threshold. The stained-glass window illuminated the toilet under the balcony. The focal point of the hall was the mezzanine balcony, which was reached after a series of decisive turns. From it one could view the front door.

135. Dining room, Herman O. Armour house. The first floor must have been at least 18′ high. In the dining room this height enabled Lamb and Rich to insert stained-glass windows between the lower section marked by the lintels of the doors, windows and the cornice of the sideboard and, above, by the paneled frieze of Santo Domingo mahogany. In contrast to the simplicity and calm of the extension table and its matching set of chairs, the semioctagonal section is confused by disparate forms and levels.

136. Hall, William S. Hoyt house, Pelham, New York; William S. Hoyt, architect, date unknown; demolished. Many of the New York families of wealth and prestige maintained a primary residence in the city and a summer or weekend retreat at the shore or in the mountains. Usually, the city house was a self-contained structure finished in stone, brick and sometimes marble, while the resort or country house, of wood or rough stone and wood, tended to engage its environment informally. Despite his Wall Street business address, Hoyt (January 1, 1847–April 27, 1905) lived in this rural area considerably north of Manhattan. His wife was the former Janet Ralston Chase, daughter of former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Salmon P. Chase. Not trained as an architect, Hoyt claimed to have designed and built the house using stones from the area for the first story and shingles for the walls above.

The interior reflected the vernacular quality of the exterior. The hall of the Hoyt house was expansive, particularly in the 50′ × 15′ section to the left of the fireplace. Instead of the Japanese vases and tufted ottomans we might expect in the city, this space was decorated with products of the wilderness and medieval weapons. Despite the refinement momentarily asserted by the foreground table and tea set, the character of this part of the hall was shaped by the simple, strong and engulfing fireplace and its inviting but hard seats. The weapon collection was assembled during European trips.

137. Hall, Swits Condé house, West Fifth Street and Seneca Street, Oswego, New York; Oscar S. Teale, architect, 1882–83; demolished 1912. Conde (April 24, 1844–January 21, 1902) and his wife, the former Apama Tucker (June 1845–October 20, 1911), invited 300 guests to celebrate the opening of this $150,000 house, “Mon Repos,” on June 7, 1883. The presence of the Utica Symphony Orchestra at this event reminds us of the wealth and influence of this upstate textile baron.

Edouard Leissner of New York City was responsible for the interior decoration. The woodwork was Santo Domingo mahogany, the ceiling was composed of flocked panels held by mahogany beams and the chimney hood and chandelier were made of antique brass. The outer panels of the overmantel symbolized Night and Morning, a clock standing between them. To the right of the fireplace was a marble-top table on which we here see a cane, a karakul hat and a card plate. To the left were Chinese porcelains and a corner bench covered with Spanish leather. The relieving vistas to the library at the left, the stairway in the center and the rear hall to the right compensate somewhat for the narrowness of this entrance hall.

In the last years of his life Conde was embroiled in numerous legal actions. In 1898 he tried to have the Navy court-martial an ensign who was seeing one of his daughters. He was fined six cents in 1900 for slandering his butler and a year later he brought suit against his son-in-law to recover $5700.

138. Hall, John L. Gardner house, 152 Beacon Street, Boston, Massachusetts; architect unknown, 1860–62; demolished. David Stewart purchased this Back Bay property for his daughter Isabella (April 14, 1840–July 17, 1924) in 1859, a year before her marriage to John L. Gardner (November 26, 1837–December 10, 1898). Because their house at 152 Beacon Street had become too small, in 1880 the Gardners commissioned John Sturgis to combine it with the single residence next door, No. 150. Though the house is no longer standing, a plaque on the site explains that Mrs. Gardner requested that the number never be used again; currently there is no 152 Beacon Street.

This photograph of the hall of the “Queen of the Back Bay” was taken when her interest in European art was growing but before she had developed, with the assistance of connoisseur Bernard Berenson, her remarkable collection of old masters now in the Gardner Museum in the Fenway. Despite the Renaissance details of the mantelpiece and the paired cathedral candlesticks and cloisonné ducks to the sides and below the inlaid painting, this hall was unusually puritanical and clean for the early 1880s. Its energy came primarily from the lathework of the balusters; its focal points, the painting and the French regimental banner, were limited in number and controlled in expression. To a greater extent than in most of these halls, the light coming from behind the balcony conservatory (John’s hobby was horticulture) and the plants themselves shaped the character of this space.

139. Hall, George Kemp house, 720 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York; architect unknown, 1879–80; demolished. Described by the Times as “one of the most widely-known men in business and social circles in this city,” Kemp (1826–November 23, 1893) was not active politically and, unlike many of the millionaires whose houses were featured in Artistic Houses, was neither a serious art collector nor a philanthropist. His wealth came through his firm of Lanman and Kemp, one of the largest dealers in drugs and chemicals in the country. His wife, the former Juliet Augusta Tryon, died four years after he did.

This broad corridor hall connected the front door with the main stairs, seen beyond the wooden archway. At the right were the doorways to the main rooms of this floor. Characterized by simplicity and elegance, the space held few pieces of furniture or artistic treasures. On the left wall was a Persian rug from the early eighteenth century and on the floor a wide Oriental runner. Neither the built-in double seat at the base of the dividing screen nor the inlaid table that held the card plate and bust was conspicuous, but they were finely crafted. Slightly offbeat though modest, this passageway probably did not prepare visitors for Tiffany’s spirited handling of the adjacent salon.

140. Salon, George Kemp house. In the early 1880s, numerous comments were published about the Kemp house, and particularly about this salon. The most exhaustive description was written for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine by A. F. Oakey in April 1882:

In this room Messrs. Louis C. Tiffany and Co. have made an elaborate attempt to assimilate the moresque idea to modern requirements, and no expense has been spared to attain the most perfect result in every respect, even the grand piano being made to assume a moresque garb …. The fireplace is lined with old Persian tile in blue, blue-greens, and dark purplish-red on a white ground, making a valuable sensation in the surrounding opal tile, of which the hearth is also composed…. The dado and the floor would not be described by the word “parquet,” being much more than this term implies—an intricate system of inlaid-work of all manner of native and foreign woods, highly polished, and forming gradations and contrasts of browns, buffs, yellows, reds, and black. All the wood-work above is executed in white holly, the panels in which are filled with various incrustations of stucco in delicate moresque patterns re-enforced with pale tints, gold, and silver. Such portions of the walls as are not otherwise occupied are covered with stamped cut and uncut velvet on a satin ground, in tones of pale buff, red, and blue, receiving the light in various ways, so that no two portions appear the same from any stand-point.

The frieze between the bands of silver and red mosaic and moulded lines of turquoise blue is brought out in bold disks at varying intervals on a buff ground, filled in with an infinite detail of silver, gold, pale purple, and white. The cornice is formed by a procession of carved silver corbels appearing against a brilliant chrome background, and on these rests the ceiling of galvano-frosted iron overlaid with geometric tracery in relief, forming hundreds of small panels of various forms, in which enrichments of gold and silver appear against the frosted background.

The panels of the bevelled mirrors above the mantel serve to reflect the white enamelled shafts in the large bay-window opposite, and the mother-of-pearl effects of the double stained glass windows draped in rich folds of olive and gold embroideries.

The furniture is all of white holly, carved, turned, and inlaid with mother-of-pearl, making rich effects with the olive plush coverings embroidered in cream and gold-colored floss.

The room is lighted by five lanterns, not including the three small ones over the mantel, which, though dimly lighted, are only intended to complete the decoration in brass and turquoise….

The only fault we think it fair to find is one for which the decorator is only indirectly responsible: the room is too small for such a treatment, and refuses in other ways to lend itself absolutely to the scheme. However, the result is a fair example of consistency throughout, as far as it is possible to be consistent in transplanting an exotic to a Northern clime, and it is to this faithful preservation of style, as well as the delicate distribution of color, that the apartment owes most of its charm.

141. Dining room, George Kemp house. According to biographer Robert Koch, this was the first house decorated extensively by L. C. Tiffany & Associated Artists. Kemp had been a friend of Tiffany’s father. The grand sideboard of the room was carved oak, the same material used for the 10′-high paneling. Above the wainscoting was a scene painted on gilded canvas of fruits, plants and vegetables, including Tiffany’s beloved pumpkins. Above two of the doors were transoms of opalescent leaded glass, similar to the frieze in theme and continuing the decoration in this register. One panel represented gourds, the other featured eggplants. In these transoms the leading was also employed decoratively as the stems of plants.

Tiffany may have utilized the glass left over from the Kemp commission in two windows for his own apartment on East 26th Street in New York. Over the four windows of the dining room were double transoms that filtered light through thin colored glass. In order to soften the relatively hard surfaces, he chose heavy hangings and portieres of embroidered plush.

As was true of his later dining room for Dr. William T. Lusk (no. 18), this one contained a simple table surrounded by studded leather chairs. Reflecting the design tendencies of the firm, but atypical of the majority of decorators in the early 1880s, these two dining rooms were defined by walls subdivided nervously into right-angled sections.

142. Library, George Kemp house. Although there are several Tiffany effects in this library, the room looked less fashionable and more traditional than either the salon or the dining room. The decorator’s hand is visible in the interlaced tracery of the transoms above the two front windows and in the iridescent shells of the coved ceiling. But the sturdy upholstered chairs, the solid bookcase and the ponderous entablature of the mantelpiece produced, comparatively, a heavier and slower-paced interior. Colors also contributed to this room’s restraint—the mahogany of the table, bookcase and entablature, the bronze plush of the hangings and the chairs and the relatively dark walls of silk topped by an even darker border of embroidered plush. Neither the bric-a-brac in the library nor the few paintings were exceptional.

143. Library, Franklin H. Tinker house, 39 Knollwood Road, Short Hills, New Jersey; architect unknown, 1878; standing. We know little about the Tinker family. Franklin H. Tinker (1853/54-May 14, 1890), the head of one of the largest trade-journal publishers in the country, Root and Tinker, was also the editor of The American Exporter from 1883 until 1887. He died at 36 of spinal meningitis, leaving a wife and one child. When Artistic Houses was published, there were approximately 35 houses in the picturesque suburb of Short Hills, a thoroughly residential planned community near Millburn, New Jersey, founded in the mid-1870s by Stewart Hartshorn. Initially, there were not even stores or a bar to disrupt this suburban fairy tale.

The original owners of “Sunnyside” were the Russells, who had moved into “Redstone” (no. 74) by Lamb and Rich in April 1882. In the same year Lamb and Rich remodeled and expanded this library to create more space for Tinker’s impressive collection of rare and autographed books. (He owned signed copies of works by Hugo, Tennyson, Ruskin, Bancroft, Whittier, Holmes, Aldrich and Strickland.) For the new walls the firm used bronzed Lincrusta (see no. 134). Although these walls and ceiling were enlivened by an allover pattern, they looked qualitatively different from the allover patterning created by L. C. Tiffany & Associated Artists. Lacking the disciplined fragmentation and abstraction of Tiffany’s work, it was, for all of its heavy energy, an inventive, vernacular summary rather than a preview of interiors to come. Mahogany was chosen for all woodwork and furniture. Above the low cases of the alcove were three stained-glass windows that symbolized, from left to right, art, science and history. The fabric casually draped over the plate on the left wall partially obscures the picture wires; below it, the large bow or butterfly of white lace is used as an antimacassar.