NICHOLAS L. ANDERSON HOUSE

Designed by Henry Hobson Richardson for its site on the southeast corner of K and 16th Streets, N.W., Washington, the house of General Anderson was singled out for commentary and illustration by critics of the period. Even Matthew Arnold, the English critic and poet, wanted to see the house on his trip through the United States in 1883–84. E. W. Lightner discussed it in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (March 1885) and Mariana Van Rensselaer in The Century (March 1886). Among the reasons for focusing on this house was the fact that it had been designed by Richardson, the architect considered not only by Americans, but also by Europeans, as the foremost architect of the country in the first half of the 1880s. Anderson may have chosen Richardson because they had been classmates at Harvard in the late 1850s. During the planning and building process, Anderson complained frequently about Richardson’s habits and demands. In a letter to his son Larz (January 1883) he wrote:

Mr. Richardson is with us, but as his valet broke his arm and did not accompany him, our Edward has had to act as nurse. He bullies and nags everybody; makes great demands upon our time and service; must ride, even if he has to go but a square; gets up at noon; and has to have his meals sent to his room. He is a mournful object for size, but he never ought to stay in a private house because he requires so much attention.

On the other hand, Richardson had reason to be unhappy with Anderson. Evidently, the General was insensitive to his architect’s deteriorating health (he died of nephritis in 1886). Furthermore, Anderson, concerned about the threefold increase from the original estimate of $33,000, complained to his friends that the cause was Richardson’s propensity to change his mind.

The house also attracted critics because it was erected in Washington, a city not previously noted for outstanding domestic architecture. According to the Washington Evening Star (August 18, 1883), quoted in the magnificently researched and clearly written Sixteenth Street Architecture (vol. 1) by Sue Kohler and Jeffrey Carson, the Anderson house “has drawn more general attention to it than is usually the case in this city, where handsome, costly residences are springing up on all sides ….”

Because Richardson’s design was not picturesque, inviting or gracious, and because Washingtonians were unaccustomed to houses expressed with such power and decisiveness, not all local reactions were positive. Defending it in another letter to Larz, Anderson wrote: “It is so essentially different from any other that the public taste must be educated up to it, and it requires a severe and well educated taste to see in its grand lines and simple beauty all that we claim for it.” Although its ground dimensions were not exceptionally large (approximately 57′ on K Street and 69′ on 16th Street), the building looked massive because of its battered foundation, its relatively plain red-brick walls and its vast roof that protected, but also appeared to exert enormous pressure on, the interior. Some thought the restrained ornament made the exterior too reserved. Van Rensselaer essentially seconded local reservations: “And Mr. Richardson has built a great brick house which is impressive because very simple and very strong, but looks a trifle eccentric—perhaps because the latter good quality is somewhat overemphasized. Mr. Richardson’s manner is, in truth, almost too monumental to lend itself gracefully to domestic work.” Today, critics tend to agree with a statement Van Rensselaer made at a later date. In her 1888 monograph on Richardson she wrote: “Yet in spite of these faults the building is a fine one—grand in mass, harmonious in proportions, coherent in design, and dignified in its severe simplicity.”

Finally, the house attracted attention because of its owners and their friends. The grandson of millionaire Nicholas Longworth of Cincinnati, Anderson (April 22, 1838–September 18, 1892) went to Harvard, studied at Heidelberg University and returned to fight for the Union in 1861. At 26 he became the Union’s youngest major general. In 1865 he married Elizabeth Kilgour, of a well-established Cincinnati family; Larz was born in 1866 and their daughter Elsie in 1874. Anderson studied law and moved to Washington in 1881. In the nation’s capital he became reacquainted with Henry Adams, whom he had met in Magdeburg in 1858. The Adamses and John Hay and his wife commissioned Richardson in 1884 to design adjoining town houses for them at the corner of 16th Street and H Street, N.W., a story systematically told by Marc Friedlaender in the Journal of Architectural Historians (October 1970).

Commissioned and designed in 1881, the Anderson house was completed two years later. The Andersons moved in during the middle of October 1883 and the following month entertained Marian and Henry Adams—the first of many bright occasions Washington society enjoyed in the house. Mrs. Anderson resided there until her death in 1917 at the age of 75. Sold by her children the following year, the house was razed in 1925 to clear space for the Carlton Hotel.

144. Hall, Nicholas L. Anderson house, 16th Street and K Street, N.W., Washington, D.C.; Henry H. Richardson, architect, 1881–83; demolished 1925. When he described this house as “easily the most interesting private residence in the capital of the nation,” Sheldon probably was thinking of its interior. From the porte-cochere or the modest main door, one entered a rectangular vestibule, paneled in oak with a tiled floor, that led to the main hall. Approximately 25′ long and 19′ from fireplace to stairway, the hall was also finished in oak. Some of the artistic highlights of this space were concentrated in the stairwell: the hand-turned balusters, the fine Egyptian screen and four stained-glass windows designed by Treadwell of Boston. Although competently handled, the remaining woodwork, including the ceiling beams and paneling, was less impressive. Opposite the windows was the fireplace with a mantel of yellow Italian marble. The first four steps of the main stairway, to the left of the clock, led to the door of the study. The door to the rear hall was concealed in the paneling at the right of the clock, and in the right-hand corner was the door to the dining room.

The plan of the first floor was excellent. The hall was impressive, implying generous-sized rooms beyond, and provided efficient access to adjacent spaces without permitting the doorways to weaken its unity or alter its character. For highlights, the Andersons depended on plants, fans and a parasol carefully placed to insure asymmetrical balance.

145. Dining room, Nicholas L. Anderson house. In this photograph the Anderson dining room appears to be one of the few illustrated in Artistic Houses in which space dominated the materials within it, although, with the table fully extended and all of its chairs in place, we might conclude otherwise. The owners did not add more furniture than necessary, tried to keep the lower paneling visible and concentrated bric-a-brac in disadvantaged places, for example, in front of the two stained-glass windows by John La Farge and below the inlaid portrait of Anderson’s father attributed to Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828). Similarly, the vases and pots were imprisoned rather than presented in the unusual recessed shelf of the mantel. On the other hand, this enabled the Andersons to show the thickness of their slab of Siena marble. Another reason the space seemed uncluttered was the size of the room, approximately 22′ square. Furthermore, the interior seemed to expand toward the concave wall of light. From the built-in seat under these six windows one could look sharply left to see the White House three blocks away. The room was also impressive because its wood surfaces were simple but not dull, for they were polished Santo Domingo mahogany. In summary, this was a dining room that was large, strong, warm, bright and uncrowded.

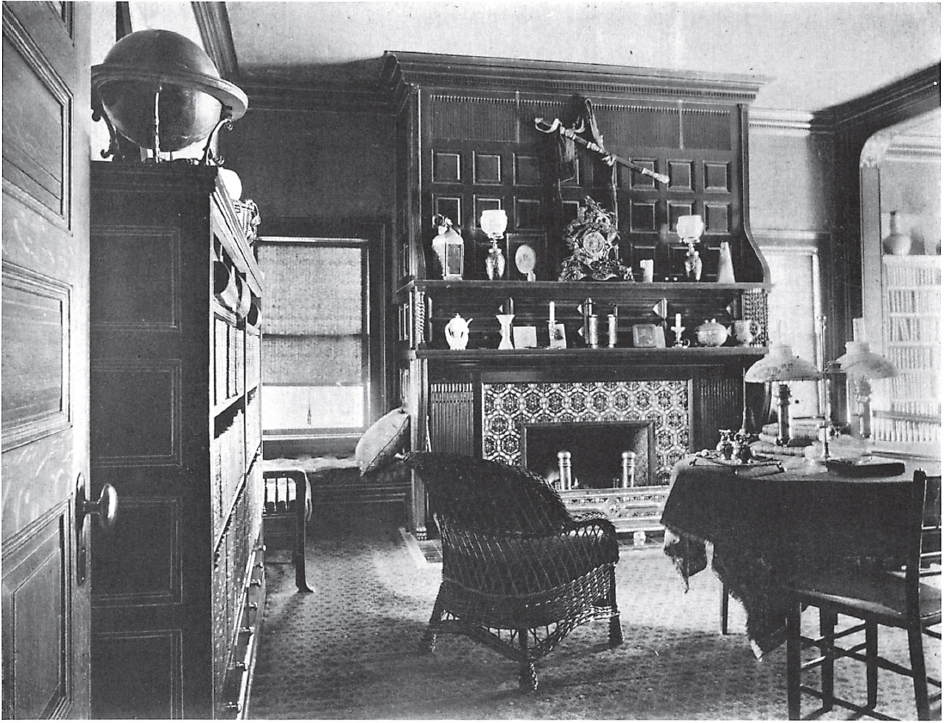

146. Study, Nicholas L. Anderson house. The room behind the fireplace in the hall was identified on the plan as a “library,” and this one off the main stairway as a “study.” The first room was a showcase library that also served as a reception room and possibly as an after-dinner smoking room for the men; the latter was a working library, the General’s den. The room was about 17′ deep and 16′ wide with a bay (7′ × 10′) at the right overlooking the stable, servant’s room and clothes yard. Beside the bay was a small lavatory. The color scheme was rather dark, some of the woodwork an olive green, and the Japanese paper of the upper walls and ceiling red and gold. With the exception of the mantel area, the study was an underdecorated interior in which shades on rollers replaced the usual curtains or drapes. However, most of the objects on the shelves were not works of art but photographs, keepsakes or lighting devices. The sword hanging on the overmantel was probably Anderson’s own from the Civil War. The wicker and side chair, like the two matching window seats, were comfortable and functional. On the table are several books, an album, a tea service and a student lamp that could be raised or lowered.

147. Hall, Walter Hunnewell house, 261 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts; Shaw and Shaw, architects, 1880–82; standing. The process of filling in the Back Bay area of the Charles River with gravel and dirt from pits at Needham, Massachusetts, began in 1857 and continued until the eve of the First World War. As the filling process moved westward, fine residences sprang up. Today this district and, particularly, Commonwealth Avenue offer in quantity and quality a collection of late nineteenth-century urban houses unmatched by other cities of the Northeast.

Designed in the “Academic Brick Style,” to quote Bainbridge Bunting, this row house, sparely ornamented with light stone facing below and brick on the upper walls, was finished between 1880 and 1882. Slightly left of center and running through four floors was a prominent bay that was the principal feature of the facade. The hall, approximately 36′ long and paralleling Commonwealth Avenue, occupied the entire front of the house. Visitors walked from the vestibule, seen in the center of this photograph, under the stairway and were immediately blocked by the landing and balustrade. Shunted to the right, they discovered the spacious and empty main hall ahead of them. Though minimally furnished, this space was handled with aristocratic simplicity. The figures and designs of the stained-glass windows did not curtail the natural lighting needed for such a deep space. This grand space became the prologue to the equally grand stairway, which made ritualistic changes of direction as it rose gradually to the next level.

This house was completed less than ten years after Walter Hunnewell (January 28, 1844–September 30, 1921) married Jane A. Peele (December 8, 1848–September 15, 1893), during the years they were raising their six children. Unfortunately, there is little evidence to suggest that children affected the design and planning of these houses, so hospitable to art and so sensitive to society approval.

Unlike many of his friends and many of the home owners included in Artistic Houses, Walter Hunnewell performed philanthropic acts and services that were not token, his primary concern being with the needy. Like his better-known brother Hollis Hunnewell (nos. 11 & 12), he was a wealthy banker and broker associated with H. H. Hunnewell and Sons.

148. Drawing room, Walter Hunnewell house. This drawing room also stretched across the front of the house, its bay and supporting Corinthian columns directly above those in the hall. The opening at the right led to a central corridor and the dining room opposite. If the main hall encouraged formal behavior, this room encouraged informal loitering. The Hunnewells chose unmatched chairs that were deeply tufted and inviting. Judging from its accessibility, good lighting, adequate space, pleasant atmosphere and books tossed randomly on the tables, this room was probably used by the family as its gathering place. Because it is so informal, open and comfortable in appearance, we may overlook the effort and expense behind some of the decoration and pieces. The ceiling, for example, was frescoed in gold, and the walls were covered with light red silk and old gold linen. On the Renaissance Revival mantel complex were glassed-in sections for choice porcelains and faience. Below, the fire opening was actually used. The dark cabinets to either side were atypically curtained. Note the combination of the wicker armchair and the highly ornate French dressing screen on the right.

149. Picture gallery, John T. Martin house, 28 Pierrepont Street, Brooklyn, New York; architect unknown, ca. 1851; demolished ca. 1897–1901. Sheldon wrote enthusiastically about Martin’s well-known collection and gallery in Brooklyn Heights:

Through the glass panels of two doors in the drawing-room the visitor receives the most pressing of invitations to enter, and, when the door has slidden aside to admit him, finds himself in a commodious and beautiful apartment, whose wainscoting of ebonized cherry is inlaid with mahogany and plain cherry and ornamented with gilt lines, and whose walls are hung with a dark, neutral-blue brocade of worsted and silk, shot through with a delicate thread of gold. One of Christopher Dresser’s papers, of a pattern probably not to be seen elsewhere in this country, covers the cove of the ceiling to the borders of the immense, oblong, octo-paneled skylight, whose wood-work again is of ebonized cherry, smoother than polished ebony itself.

The prize work was Going to Work, Dawn of Day by Jean-François Millet, seen directly behind the sofa at the near left. Sheldon was also pleased to see La Charrette by Corot and two paintings by Narcisse-Virgile Diaz because they proved that American collectors were beginning to discover the Barbizon school of French painting.

Despite these recent purchases, most of the 80 paintings in the Martin house either recounted history or doted on life’s messages. Immediately above the Millet was A Charge of Dragoons at Gravelotte, which Alphonse de Neuville painted to order in 1879. Directly above the folio cabinet was a painting that illustrated the virtues of life, Reapers’ Rest (1873) by Jules Breton. Above and to the right of this painting was another moral poem, The Spirit Hand by Gabriel Max (1840–1915), which the Martins ordered in 1879.

150. Picture gallery, John T. Martin house. Martin (October 2, 1816—April 10, 1897) had made his fortune from the clothing contract he had with the Union Army and from his even more lucrative banking and real-estate ventures after the Civil War. He lived in a Greek Revival house on Pierrepont Street with his wife, the former Priscilla Spence, until 1895, when they moved to 20 West 57th Street in Manhattan. The major pieces of this collection were purchased after the Centennial in Philadelphia and the gallery, built as an addition on the east, was probably constructed in the last half of the 1870s. Comfortably furnished, it looked more like a living room than most private New York galleries of the day, but it was also functional with its drawers and cabinets and with its gas jets and raised skylight to provide illumination.

Despite his late interest in the Barbizon school and his acknowledgment of the Japanese influence after the Centennial (evident here in the prizewinning vase by Tiffany from the Parisian Exposition of 1878, seen between A Charge and Reapers’ Rest), Martin’s paintings were becoming old-fashioned in the 1880s. Auctioned on April 15 and 16, 1909 in New York, these canvases brought only $281,000. Although bidders competed for the Barbizon landscapes and peasant pictures, Martin’s anecdotal and sentimental paintings had fallen from grace. The Millet went for $50,000 and the Corot for $30,000, but A Charge was sold for only $10,200, Reapers’ Rest for $6000 and The Spirit Hand for $1600.

151. Dining room, John T. Martin house. Because of the limited floor area and high ceiling that marked this house as a product of the 1850s, this interior did not resemble the spacious, professionally designed dining environments popular in New York in these years among families of means. Its size, however, did not discourage the Martins from displaying numerous choice objects and china; nor did they stint on the quality of the materials. The chairs, based on a Louis XIII model as the table probably was as well, were made of carved mahogany, which was also used around the closed fireplace and for the buffet to the right. Stamped leather covered the walls and hand-painted canvas was used to finish the ceiling. The hangings were made of bronze plush. The unidentified scene above the mantel of two dogs contemplating a hanging fowl may have been a fragment from a tapestry.

152. Dining room, Joseph S. Decker house, 18 West 49th Street, New York, New York; architect unknown, 1881–82; demolished. At the age of 20 Decker (ca. 1836–January 28, 1911) began his career, probably with the help of his banker father, in the banking house of Turner Brothers in New York City. Eventually he formed his own firm, Decker, Howell and Company, which in the early 1880s helped the Northern Pacific Railroad secure a $40 million loan to complete its road to the West. Decker retired about 1901; his wife and only child died before he did.

Cottier and Company, New York decorators, was responsible for the expensive front parlor, but it is not known to whom the decoration of the dining room was entrusted. Falling between success and failure, the room looks like a representative outcome of abundant money in search of artistic and social approval, producing a strong interior dominated by the dark mahogany of the wainscoting, mantelpiece and ceiling beams. Despite a few unusual features, such as the mural of the coved frieze above the mantel, the leaded window and the birdcage in the corner, decorative risks did not dominate this interior. Though proper, the Decker dining room looks eclectic or somewhat hollow, as if its expression was superimposed rather than revealed.

153. Hall, Henry J. Willing house, 110 Rush Street, Chicago, Illinois; Palmer and Spinning, architects, 1880–81; demolished before 1909. After spending his working life in dry-goods businesses in Chicago, Henry Willing (July 10, 1836–September 29,1903) retired in 1883 as a junior partner of Field, Leiter and Company (renamed Marshall Field & Co. in 1881). He retired early to spend more time with his wife Frances Skinner, whom he married in 1879, and his two children.

Willing took the responsibilities of wealth seriously. He worked hard to strengthen public institutions and support causes that he thought would improve the quality of life in Chicago—the Y.M.C.A., Chicago Home for Incurables, Newberry Library, The Art Institute of Chicago and Chicago Historical Society. Though deprived of much formal education, he was actively curious about the past. In this distinctive hall, he expressed his fascination for history earnestly though perhaps naively.

Frederick Almenralder (1832–?) of Wiesbaden and Chicago took 14 months to carve the mantelpiece. Inspired by illustrations by Gustave Doré (1832–1883), the nine scenes were (left to right): Rebecca, a corner statuette of Oliver Cromwell, Moses, Solomon, in the center Michelangelo’s seated Moses, Abraham and Isaac, Daniel among the lions, a corner statuette of Richard Cœur-de-Lion, and Ruth gleaning. The frieze below these figures contained the coats of arms of leading nations: Germany, the United States and Great Britain in the middle. The portieres from India and rugs woven in Paris contributed color to the hall finished in white oak.

154. Library, Henry J. Willing house. The house contained some unusual copies of Western masterpieces. Resting on engaged Doric columns, the frieze that divided the library into two sections was a diminutive version in mahogany of the north frieze of the Parthenon. Another distinctive reproduction in the library was that of the Cumean Sibyl, the central figure carved on the mantelpiece in the second room. Carved in Iowa stone, the figure had been adapted from Michelangelo’s painting in the Sistine Chapel. Above the mantel are more common reproductions. From the right, the first framed picture is a Raphael self-portrait and the fifth the Four Apostles by Albrecht Dürer. An enthusiastic innocence characterizes Willing’s peculiar assemblage of great works.

The portieres that divided the rooms were reportedly from a private apartment of the Empress of China, and the table in the foreground, of cedar of Lebanon, was once owned by Maximilian of Mexico. For all of its ingenuous effects, this library looked surprisingly comfortable, its feeling of informality being conveyed through the tacked carpet, slanting stacks of books and modest furniture.