The Phillips family purchased a lot at the corner of Berkeley and Marlborough Streets in Boston in 1877 and commissioned Peabody and Stearns to design a house for it, one of only two freestanding houses in the Back Bay district. The house, according to Peabody biographer Wheaton Holden, was French Renaissance with châteauesque features. Though not one of the first ten, this was the only house in Boston cited in American Architect and Building News’s celebrated poll of 1885 to determine the most beautiful buildings in the United States. Nevertheless, it was not one of the most successful designs of Peabody and Stearns.

Phillips (October 21, 1838–March 1, 1885) was a socially respected and philanthropic Bostonian whose ancestors had founded Water-town, Massachusetts in the 1630s. An inheritance from a distant cousin in 1873 influenced the rest of his life. That year he formed John C. Phillips and Company, an import firm concentrating on trade with China and the Philippines. He spent most of 1874 traveling in Europe, and the following year married Anna Tucker of Boston. They had five children, the best known being ornithologist Charles Phillips.

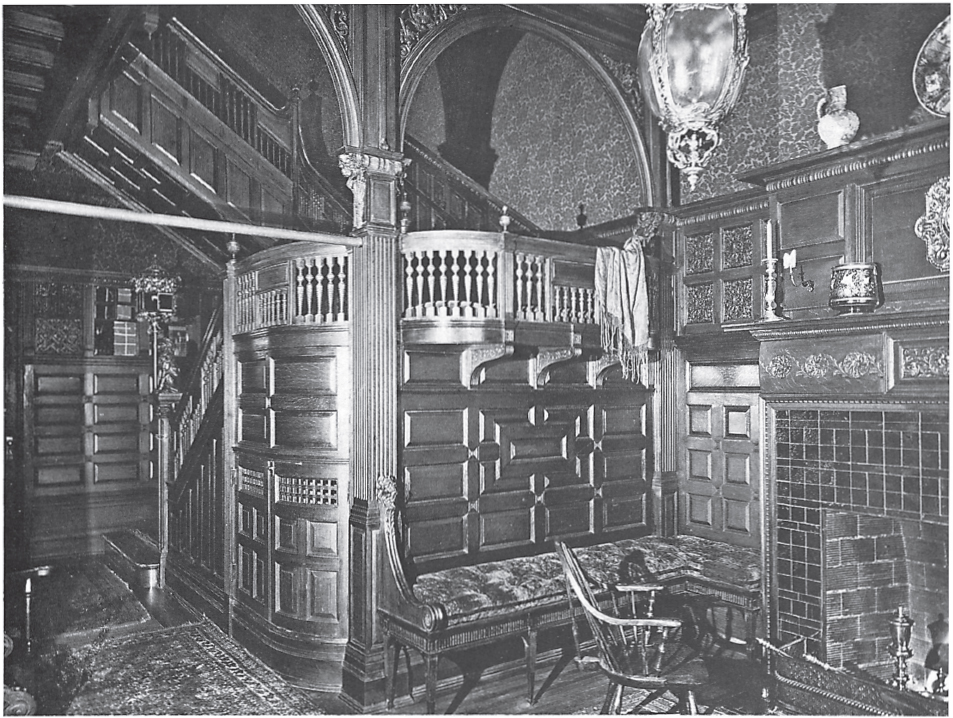

163. Hall, John Charles Phillips house, 299 Berkeley Street, Boston, Massachusetts; Peabody and Stearns, architects, 1877–79; demolished 1939. The shape and placement of this hall and stairway were somewhat unusual. The hall was shallow, in part because of the deep entranceway and in part because of the advancing, centrally placed stairs. The stairway probably was featured because of its carved frieze of garlands, formidable newel posts and distinctive balusters and panels. The effect of its projection into the hall was to invite visitors to move ahead rather than horizontally into the reception room to the right or the drawing room to the left. The rear hall, off-center at the left, led to the parlor behind the drawing room but did not service equally well the two rooms behind the reception room on the right: the library and dining room. Nevertheless, this space illustrates the local preference for beautifully shaped and finished wood, and though the scale of the architectural decoration may have been too large for the setting, the oak, red-painted walls and portieres of embroidery on olive-green plush probably added sufficient warmth to make this a pleasant central area of family movements.

164. Drawing room, John Charles Phillips house. This room leaves the impression of relaxed and durable wealth confident enough to combine favorite items with disconnected objects in a setting that was usable and comfortable. The shelves contain pieces that Phillips probably acquired in 1860–62 while in India and the Far East. These are displayed unself-consciously alongside Western objects such as the bronze and marble French mantel clock and the porcelain vase on the table. Above the mantel is a painting by the German artist Adolf Schreyer, and in the passageway separating the drawing room and parlor stands Thomas Crawford’s statue Cupid in Contemplation of the early 1840s. In these two rooms were paintings by Bouguereau, Daubigny, Ziem, Corot and Alfred Stevens (1823–1906) indicating the interest of Mr. and Mrs. Phillips in Barbizon work as well as the more conservative nineteenth-century schools. Above the fireplace is a Middle Eastern scene by Eugene Fromentin (1820–1876).

165. Dining room, John Charles Phillips house. This dark, strong interior implies that eating here was a very serious, if not primarily male, affair. The ceiling was painted in oil to represent growing pomegranates and the walls hung in jute in variations of green. Evidently the men retired after dinner to the large chimney nook to smoke and converse. Rarely in these photographs do we see logs burning. Although this dining room was too weighty both in color and in its woodwork and furniture to be modish, it offered, like the drawing room, a pleasant and reassuring domestic atmosphere.

166. Hall, James W. Alexander house, 50 West 54th Street, New York, New York; Robert H. Robertson, architect, 1881–82; demolished 1906. The halls on these two pages represent three versions of the “living hall,” in which the woodwork played a significant decorative role and the setting was relatively informal. This kind of hall would have been more common in the suburbs (Hinckley) or the country (Wadsworth) than it would have been on West 54th Street in New York City. Warm, comfortable and unpretentious, the central space in the Alexander house seems modest for an expensive brick house of four floors. Alexander (July 19, 1839–September 21, 1915) joined the Equitable Life Assurance Society in 1866, was first vice president of the firm when his house was built and served as its president from 1899 to 1905. He married Elizabeth B. Williamson (November 24, 1862); they had three children.

After crossing the threshold, one immediately sensed the invitation to relax offered by the fire and the warm glazed tiles of the fireplace, open-arm Windsor chair with plank seat, built-in cushioned chimney seat, warm stained-oak paneling and red and gold portieres pushed aside to reveal the stair hall. Because it was physically connected with the main stairs, this section of the hall, paradoxically, offered protection and freedom, stillness and movement, reassurance and adventure. The architect, responsible for designing the carved mantel face, paneling, cupboards, brackets and stair railing was the real decorator of this part of the house.

167. Hall, Samuel P. Hinckley house, Central Avenue and Hicks Avenue, Lawrence, New York; Lamb and Rich, architects, 1883; demolished. Unlike the dark, semienclosed Alexander hall, this was a light, porous space. The hall was not intended to be seen as an isolated compartment, but as a spatial link fluidly connected with the dining room, through the wide double doors on the left, and with the parlor, entered at the base of the stairs. Uncluttered by city standards, this summer-house hall contained several distinctive pieces and features: the Brewster and Carver armchairs on the left, the eighteenth-century grandfather clock, the Dutch door, the transomed English casement windows and the rampant lions in relief between the brackets of the mantel hood. The leopard skin and animal rug were casual touches considered appropriate in a semirural setting.

“Sunset Hall” was one of five houses designed for Hinckley’s estate (see Building, September 1888) by Lamb and Rich, among the least inhibited and most sensuously playful architects of the early 1880s. Initially a builder in Lawrence and by the mid-1890s successful in real estate, Hinckley (1850–October 20, 1935) and his wife, formerly Rosalie Neilson, were peripheral figures of New York society. They separated in 1910.

168. Hall, James W. Wadsworth house, Avon Road, Geneseo, New York; architect unknown, 1835–38; standing. James Samuel Wadsworth, the father of James W., had married Mary Craig Wharton of Philadelphia in 1834, and while touring Europe the couple met Lord Hartford in London, were impressed by his Regent’s Park mansion and asked him for its plans in order to erect a similar house in Geneseo. “Hartford House” was occupied in 1838. James W. (October 12, 1846–December 24, 1926) inherited the house and 8000 acres of valley land in 1872 and on September 14, 1876 married Marie Louisa Travers of New York City. They had a daughter and a son, James W., Jr., who served in the United States Congress for 35 years. James W., Sr., served in Congress for 16 years before his retirement in 1907. Known as “The Boss,” he ran an extensive farming and cattle-raising operation in Livingston and adjoining counties.

Europeans in the 1880s often interpreted the absence of a separate vestibule in American houses as a sign of Yankee confidence in the surrounding community. Here one walked directly into a sitting hall that was attractively supported by a stair hall containing columns, screen, paneling, balustrade, landing and stained-glass window. The low couch, Windsor and Bar Harbor wicker chairs, steerhorns and bison head, and functionally placed hat rack conveyed an immediate impression that the Wadsworths, not a New York decorator, determined the artistic tone of their house.