The Madison Avenue facade, the hotel tower rising at the rear.

Although his rapid rise and dramatic fall were not uncommon in the 1870s and 1880s, the early years of Villard (April 10, 1835–November 12, 1900) were atypical of the beginnings of most late-nineteenth-century American millionaires. Born in Bavaria, he studied briefly at the Universities of Munich and Würzburg prior to his emigration in 1853 and began his life in the United States as a sophisticated European, not a pragmatic Yankee. He had little to do with business initially, and his friends were not the “prosaic moneymen” whose reputations were already known in Europe. Villard became a journalist and war correspondent for several newspapers, among them the New York Herald, New York Tribune and Chicago Daily Tribune, and his sympathies for the Northern cause led to friendship with abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and to marriage with his daughter Fanny on January 3, 1866. At the height of Villard’s journalistic career, he owned the New York Evening Post and The Nation, the latter one of the leading liberal journals of the day.

Villard became publicly involved in railroad speculation in 1873 when he represented the interests of German bondholders in the Oregon & California Railroad. Eight years later, with the aid of the so-called “Blind Pool”—investors did not know the ultimate destination of their money—he purchased a controlling interest in the Northern Pacific Railroad. His reputation as a wunderkind soiled through overspending, Villard resigned the presidency of the railroad early in 1884. Although he was later reaccepted by the New York business community as well as by the directors of the Northern Pacific, he never again equaled his startling successes of 1881–83.

Villard did not follow the millionaire crowd when he purchased this site on Madison Avenue, behind St. Patrick’s Cathedral, for $260,000 in 1881. Fifth Avenue, not Madison, was then the desired address. Furthermore, he rejected the common relationship between a New York City residence and the street in preference for one reflecting European planning. The U-shaped plan of the house was built around an almost square courtyard that was separated from the public space of the sidewalk by a metal fence. Larger than the William H. Vanderbilt house on Fifth Avenue, it was designed to accommodate several families—another European approach. Villard planned to occupy the south wing (451 Madison Avenue) at the corner of Madison and East 50th Street. Behind the building on this 200′-deep lot, he envisioned a garden shared by those who purchased the remaining sections.

The brother of Mrs. Villard was married to McKim’s sister, in all probability, Villard and the firm agreed upon the shape and stylistic character of the house though its details were worked out by Stanford White’s assistant, Joseph Wells. Evidently Villard overrode the firm’s preference for light stone. In The Century Magazine (February 1886), Mariana Van Rensselaer, noting the choice of brownstone for this modern Renaissance palace, expressed a common reaction by calling the effect “very quiet, a little cold, perhaps a little tame.” However, she also stressed the “refined” character of the house and its contrast to surrounding “vernacular” designs inspired by similar sources. Referring to it as more grand than beautiful, The Architect of London (January 12, 1884) thought it was the “first attempt made to reproduce an Italian palace in America.”

The Madison Avenue facade, the hotel tower rising at the rear.

Construction began on May 4, 1882. When his Northern Pacific operation collapsed a year and a half later, Villard moved his family from an expensive hotel to the unfinished mansion to save money. Hounded by citizens and the press, who thought that by this act Villard was mocking those who had lost money in the crash, the family moved out the following spring, bravely declaring it was doing so “without regret.” Two years later their quarters were purchased by Mrs. Whitelaw Reid.

In the mid-1970s the Catholic Archdiocese of New York, which had used the Villard-Reid mansion since the 1940s, leased the site to hotel developer Harry B. Helmsley. He and architect Richard Roth, Jr., of Emery Roth and Sons, proposed the demolition of parts of the rear of the mansion to join it to a new hotel-office tower behind. Many groups and individuals in New York objected to the original plans because they would have eliminated some of the celebrated spaces, including the music room (no. 188), later called the Gold Room when it was remodeled by McKim, Mead and White for the Reids in the 1890s. After several years of spirited discussions about the future of the houses, construction of a 51-story hotel—the Helmsley Palace—began on March 14, 1978. The hotel opened in March 1981. Breakfast, tea and cocktails are now served in the Gold Room. According to William Shopsin and Mosette Broderick, who have recently published a solid history entitled The Villard Houses: Life Story of a Landmark: “the long debate about the fate of the Villard houses resulted at last in a creative marriage between preservation and development, an encouraging conclusion to a difficult chapter in their history, and a promising beginning for their second century.”

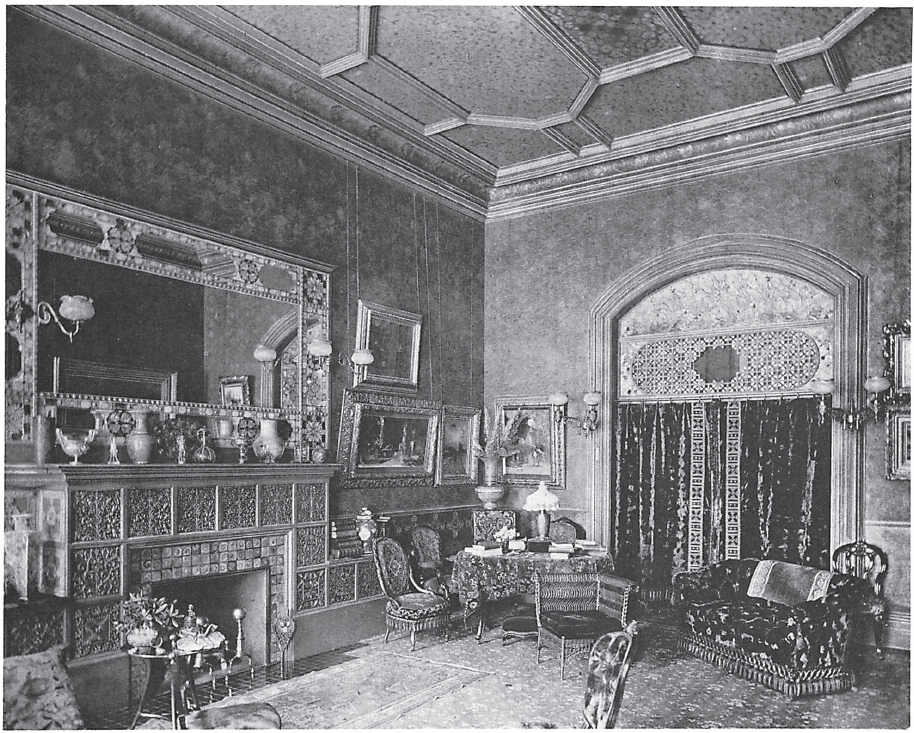

183. Reception room and hall, Henry Villard house, 451 Madison Avenue, New York, New York; McKim, Mead and White, architects, 1882–85; standing but altered. The main entrance to the Villard section of the building was in the middle of the south side of the court on East 50th Street. In this photograph the entrance to the hall is on the left just beyond the square opening; the reception room is in the foreground. This vista, looking east, revealed a long, impressive corridor illuminated by the light coming from the stairway on the left and the music room at the end. The fireplace on the right had a marble mantelpiece with an overmantel by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907) depicting peace as a female figure flanked by two children. Mexican marble and inlays of marble covered the walls, and the floor and groin-vaulted ceiling were finished in mosaic. Although the seats in the hall indicated it could be a lounging area, it is difficult to imagine this hard, shiny environment used except for traffic. By contrast, the reception room, the central section of a three-part drawing room, though proper and intentionally balanced, was much less formidable. The pilasters on either side of the doorway were inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Like some of the wall spaces of the drawing room, the Turkish frame furniture was covered with terra-cotta silk embroidered in orange-yellow.

184. Stair hall, Henry Villard house. The shimmering marble stairway to the second floor has been freed of its grime and polished to its original luster, making it one of the most exquisite spaces of the new Helmsley Palace Hotel. The reflections from the finished panels of Siena marble transform the area into a visual experience. This dark photograph shows the upper landing of the stairway, the triple arcade and the hall of the second floor—a hall that was less splendid but warmer than the one immediately below. The transition from the semipublic space below to the private space above was marked here by the shift from marble to leather-covered walls. On the second floor there were three bedrooms, three bathrooms, a library and a boudoir; on the third, five bedrooms, four bathrooms and a boudoir; on the fourth, 12 bedrooms and three bathrooms; and on the fifth, at least a dozen bedrooms.

185. Hall, Henry Villard house. The round-arch construction of the sturdy ceiling is divided into bays by unribbed, mosaic-decorated groin vaults. Despite the cost, craftsmanship and quality of materials, the effect of the Villard hall is authoritative but not encouraging, leaving the visitor with unanswered questions about what lies beyond the closed drawing-room doors of this architecturally orchestrated ritual of passage.

186. Drawing room, Henry Villard house. This room, part of the triple drawing room that could be treated as a single social space, was located in the southwest corner of the mansion. Although the stained cherry woodwork was dark, the space was adequately lighted by the East 50th Street windows at the right and the Madison Avenue window, behind the photographer. At the left is one of the four freestanding segmentally fluted columns at the entrance to the hall, and beyond the opening are several stained-glass panels of the front door. The wall surface of the drawing room, composed primarily of panels separated by pilasters, was inlaid with white mahogany, satinwood and holly, in addition to mother-of-pearl. Built to call attention to selected bric-a-brac, the two fluted niches at the sides of the mantel complemented similar forms at the opposite side of the drawing room. When the Whitelaw Reids remodeled the drawing room in 1891, they removed some of the paneling but left the plaster ceiling, the mantel of onyx and the parquet floor. In transforming the drawing room into the Madison Room, a chandeliered cocktail lounge of the Helmsley Palace, the mantelpiece was discovered behind built-in office cabinets.

Sheldon made an odd observation about the Villard house: “No attempt at ostentation appears in any part of the architectural outline or the decorative scheme. Not only good taste prevails, but good taste as understood by persons of refinement and education and experience.” Perhaps he was moved to write this because serious demeanor triumphed over the bizarre in every square inch of this house. Perhaps his reaction was affected by the absence of portieres and other drapery or the fact that the house was not completely furnished when these photographs were taken. When he used “ostentation,” he was evidently not thinking of size, for this was the largest building of its kind in the city, or of cost, for it amounted almost to a million dollars.

187. Dining room, Henry Villard house. Located between the fireplace of the hall and the doors to the music room were sliding doors leading to the dining room (20′ × 60′)· The west third could be closed off by a movable screen and used as a breakfast or informal dining room. The focal point of the dining room was the vast fireplace complex with two recessed basins and busts symbolizing joy, moderation and hospitality carved by Saint-Gaudens. The unit has been moved in its entirety to the center of the lobby of the new hotel. The walls were profusely carved and the panels between the ceiling beams finished in Lincrusta, indicating the decorator’s determination to avoid a vacuum. If the eye tired of these visual delights, it could read old sayings about the joys of good friends and good food worked into the frieze and other registers in white mahogany.

Channing Blake (Antiques, December 1972) commented perceptively about the role of the black English oak furniture:

The furniture was laid out in dogmatic Renaissance patterns. There was a heavy table in the center with a chair at each end, while all the rest of the chairs, and a chest or credenza or two, were backed stiffly up to the wall. White used furniture as the Italians and French had done for centuries; as rhythmic punctuations along the long expanse of a wall. The furniture thus became part of the walls rather than elements in the room’s space.

188. Music room, Henry Villard house. The music room, now the Gold Room of the Helmsley Palace, was bathed in light from stained-glass east windows. The Gold Room today looks much more inviting than the cavernous and unfinished space in this photograph. Some surfaces of the room have changed little—the carved paneling at the base, the relatively neutral middle section and the frieze. This photograph makes the music room look barnlike and bare, in part because the barrel-vaulted ceiling had not yet been decorated by Stanford White and the lunette above the cornice had not yet been painted by John La Farge. The musicians’ gallery, reached by the door in the far-right corner, remains, as do five well-preserved plaster casts of a work by Luca della Robbia (ca. 1400–1482), the Cantona, originally in the Cathedral of Florence. Five additional panels from the Cantoria were installed on the opposite wall, above the doors to the dining room. Shopsin and Broderick point out that Villard, in Rome in 1874, studied fifteenth-century Italian sculpture and returned with casts of work by della Robbia, Donatello, Ghiberti and Verrocchio.

189. Guest room, Henry Villard house. Despite the rich carving of the canopied bed, a bureau, the corner of which is seen at the left, and the fireplace, this guest room, like many of the Villard rooms, seems unexpectedly barren. The bare hardwood floor accentuated this appearance of spareness. Crimson-and-gold brocade covered the walls. The ceiling was divided into rectangular panels by beams. The woodwork was oak.

Judging from the absence of chandeliers in most of the Villard interiors, these rooms were probably not well lighted after dark. Although gas was the principal source of artificial light, the Edison Electric Lighting Company had installed wiring for later use. Impressed with the formidable interior decoration, critics have tended to overlook the modern conveniences of the Villard house. Its central-heating system consumed almost a ton of coal each day. There was also a hydraulic elevator off the vestibule. In Villard’s section of the mansion there were 13 flush toilets.

190. Dining room, Richard T. Wilson house, 511 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York; architect unknown, date unknown; demolished 1915. Once known as the “Old Tweed Mansion,” the home of “Boss” Tweed, the Wilson house was a four-story brownstone on the southeast corner of Fifth Avenue and East 43rd Street. Built in the 1860s, its principal rooms were small and dark measured by the standards of the affluent in 1882, the year the Wilsons moved in. The Renaissance Revival redecoration, probably done by the New York firm of Duncan, Johnston and Fenton, was heavy for the room’s size. The wall was divided into two basic parts: Below were the dado and woodwork of oak and above were disparate sections of nineteenth-century French tapestries. The built-in oil painting and fringed drapery over the fire opening, as well as the shiny andirons and absence of a screen and tending equipment, suggest that the fireplace produced more conversation than heat. When extended, the table probably accommodated ten.

Like their dining room, the Wilsons were more determined than casual and more calculating than graceful. They settled in New York City after the Civil War, during which Wilson (1829–November 26, 1910) had been a commissary general in the Confederate Army and also sold the South’s cotton in Europe. With a modest fortune of $500,000 from the cotton transactions, he founded the banking firm of R. T. Wilson and Company and by the mid-1870s was regarded as a minor millionaire on the fringes of New York society. Mrs. Wilson, the former Melissa Clementine Johnson (ca. 1831–May 29, 1908) of Macon, Georgia, was a shrewd matchmaker for her children—so shrewd that the family became known as the “marrying Wilsons” or the “devouring Wilsons.”

191. Dining room, Edward E. Chase house, 14 West 49th Street, New York, New York; architect unknown, 1882–83; demolished. This dining room was decorated by John C. Bancroft of Boston, who used inlaid woods extensively and contrasted heavily patterned sections. The ceiling, for example, was an intricately pieced mosaic of mahogany, sumac and walnut. Around the mantelpiece and at the side of the large buffet, Bancroft used strips of brass and silver to divide the inlaid wood into a checkerboard design. The most extravagant display of pieced work was his handling of the jambs and lintel of the wide opening that separated the two rooms. Above the wainscoting, the wall was covered with golden “Japanese cloth” that was partially covered by prints of landscape and peasant themes in frames that were also designed by Bancroft. Despite the apparent attempt to define this environment through planes of abstract energy, the results are more overbearing and relentless than the designer may have intended.

Chase (ca. 1841–April 23, 1900) was a minor New York broker closely associated with the Iowa Central Railroad. Mrs. Chase died childless in the early 1890s; he retired in 1898.

192. Library, George P. Wetmore house, Bellevue Avenue, Newport, Rhode Island; Seth Bradford and Richard Morris Hunt, architects, 1851–52 and 1869–73; standing. The original house on this site was erected in 1851–52 for William Shepard Wetmore, a merchant who traded with China. It was designed by local builder Seth Bradford. Despite its reputation as the finest house in Newport, George Peabody Wetmore (August 2, 1846–September 11, 1921), who had inherited the property from his father, asked Richard Morris Hunt to remodel and enlarge it. Hunt transformed “Chateau-sur-Mer” by adding a vast billiard room and splendid staircase on the north and a dining room on the east and by replacing the old dining room with a new library on the west. Hunt’s work was begun in 1869, the same year that Wetmore married Edith Keteltas. Governor of Rhode Island for two terms, Wetmore also served as a United States Senator from 1895 until 1913. Further changes were made in the house in the 1880s.

The walnut surfaces of the library were the work of noted Florentine carver Luigi Frullini. According to Winslow Ames (Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, December 1970), the Wetmores may have met Frullini while on their wedding trip. He was responsible for the competently designed and carved arabesques of the frieze and at either side of the fire opening, the frequent pilasters that emphasized the height of the ceiling and an elaborate built-in writing desk. The walls of stamped and painted leather were partially obscured by paintings and Chinese chargers. Other souvenirs of the family’s China contacts were displayed on the tops of the bookcases and at the sides of the desk. By the fireplace a Chinese ceramic pug stands guard by a doghouse.

193. Dining room, George P. Wetmore house. Winslow Ames explained that in the dining room Frullini was responsible for the twin sideboards, serving tables and overmantel. The sideboards, heavily ornamented with small relief busts and bunches of grapes and supporting Bohemian wine sets, were pressed so tightly against the ornate mantelpiece, festooned with drunken putti above and painted with an Italian majolica hunting scene below, that the whole became a single decorative unit that upstaged the fireplace’s function. Opposite, according to Ames, the majolica was repeated in a plaque inserted in the woodcarving over the sideboard, its ceramic blue and yellows joining the walnut of the wood and the polychrome of the wall “in an extraordinary florid celebration of the hunt and of food.” Despite this outburst, which continued around the room in the painted leaves, this dining room also expressed soberer thoughts. Exceptionally large (23′ × 33′ and 17′ high), it did not look crowded. The respectable family portraits matched the American Empire dining table.

194. Hall, William Clark house, 346 Mount Prospect Avenue, Newark, New Jersey; Halsey Wood, architect, 1879–80; standing. Trained in his father’s cotton-thread business in Paisley, Scotland, Clark (1841–July 7, 1902) arrived in the United States with his brother George in 1860 and settled in Newark four years later. There the two brothers began to manufacture spool thread in a small factory on the banks of the Passaic River. By the 1880s the factory had expanded to both sides of the Passaic and employed several thousand workers. The management was praised at that time for its concern for its employees.

Clark was survived by his second wife, the former Jennie Waters, and four children, two from each of his marriages. A yachting enthusiast, he died aboard his yacht at Portland, England. During the last five years of his life, his primary address was Largs, Scotland.

Renovated after a destructive fire in 1976, the house is now known as the North Ward Educational and Cultural Center. One entered the original vestibule through brass-mounted doors of ebonized oak and proceeded from the vestibule into the main hall (22′ × 26′)· On the left was the staircase; directly ahead, the dining room. Though large, the hall was relatively simple—too simple for the ornate, lumbering stairway that demands our attention. The architect and decorator seem to have consciously minimized the oak wainscoting, neutral wallpaper and simple frieze to prevent competition with the overstated stairway. The broad stairs rose slowly and heavily to a landing 8′ above the floor and from there continued around an open shaft to the top floor. Conspicuously placed on the carpet is an armchair made from the horns of Western animals and cattle, a type that was popular in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

195. Dining room, William Clark house. Apparently, the objective of the Clarks and Wood here was a dining room that looked modern, one free of high-relief ornament, grave walls, oppressive hangings and cumbersome furniture. Although they avoided these features, they did not replace them with a coherent program. To counteract the height of the ceiling, they divided the walls into registers that were too numerous and too strongly differentiated. These attempts to minimize the impression of height resulted in a complicated wall plane that served as a poor backdrop for featured pieces. For example, the two side tables looked dwarfed and the paintings as if they had been “skied” by a revengeful exhibition hanger. Furthermore, the setting lacked consistency; the wall opposite the one illustrated contained windows of stained glass held in place by robust stone mullions. Yet the room was neither pedantic nor pretentious; it was a product of goodwill and innocence and, consequently, had a charm of its own.

196. Drawing room, William Clark house. Unlike the dining room, the drawing room was pretentious. Its dominant central feature was the ottoman, upholstered in damask and supporting a Chinese porcelain bowl on its column. The ottoman, with the complicated gasolier above, became, in effect, a static carousel that obstructed traffic and devoured space. But at least this piece of furniture was given sufficient space for its richness to be appreciated. Unfortunately, this was not true elsewhere. Fabrics competed with the mantel shelf of Mexican onyx and columns of white marble. The heavy flowered drapes to the right, selected to complement the stained-glass windows, actually weakened their effect. The glass and drapes formed a screen two feet from a heavily mullioned bay window. If this wealth of fine stuffs is too strong for twentieth-century tastes, it was acceptable to Sheldon: “The walls of the drawing-room, finished in satin-wood, and decorated in ebony and gold, are upholstered in a rich, tufted silk damask, with a dark-red border at the angles, giving a prevailing effect of a golden glow of color, to which the quiet, rich tone of the carpet is auxiliary.”

197. Library, J. Coleman Drayton house, 374 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York; McKim, Mead and White, architects, 1882–83; demolished. Historians have not been kind to J. Coleman Drayton, focusing almost exclusively on his divorce, one of the most publicized scandals of the 1890s. In 1879 he had married Charlotte Astor. On March 18, 1892 he read in the New York Sun that she had run off with their next-door neighbor in Bernardsville, New Jersey. Before their divorce was settled in December 1896, New York gossips had a field day.

The Draytons moved into this house, one of the earliest urban projects of McKim, Mead and White, in 1883 but relocated in Bernardsville in 1886. Despite Sheldon’s report that the library contained shelves loaded with books two and three deep, this photograph implies the room was an obligatory gesture seldom put to use. Certainly, the room was distinctively furnished. There were Beauvais tapestries of hunting scenes on all the walls, printers’ marks of the sixteenth century painted within the ceiling frames of ebony, a musicians’ gallery at the right fronted with a screen of Chinese latticework and a hand-carved Renaissance-style table in the center. But the suggestion of emptiness persists. Perhaps the Draytons had moved in only shortly before this photograph was taken.

198. Drawing room, John Taylor Johnston house, 8 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York; architect unknown, 1856–57; demolished. Johnston (April 8, 1820–March 24, 1893) is primarily remembered as the first president (1870–89) of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Although he passed his bar examination in 1843, he acquired his wealth through the Central Railroad of New Jersey. He married Frances Colles (d. July 20, 1888) on April 15, 1850; they had four daughters and one son.

Before it was dispersed at auction in December 1876, the Johnston collection of approximately 200 oils was probably the finest in the United States. It consisted of outstanding American painters (West, Allston, Stuart, Sully, Trumbull, Cole, Homer, Church) as well as works by the popular, conservative artists of contemporary France and Germany. Johnston realized $300,000 from the auction, evidently held to meet his debts caused by the depression of 1873–77.

Johnston’s drawing room had recently been redecorated by L. C. Tiffany & Associated Artists. They had created a warm environment using salmons, red, yellows and browns. Above the double doors they inserted a latticework transom that contained pieces of colored glass. Most of their effort, however, was concentrated on the mantel area where they surrounded the bevel plate mirror with smaller mirrors held by frames of leaded glass. The fire front was faced with panels of East India teakwood and tiles of Siena and colored glass. The pattern of the ceiling was applied by a palette knife while that of the wall was brushed on.

199. Library, Rectory, Trinity Church, 233 Clarendon Street, Boston, Massachusetts; Henry Hobson Richardson, architect, 1879–80; standing. The first rector to occupy the residence was The Right Reverend Phillips Brooks (December 13, 1835–January 23, 1893), who had been called by the parish in 1869 and under whose charge the new Trinity Church on Copley Square was built and finally consecrated in February 1877. A brilliant preacher whose liberal social and religious views were well publicized, Brooks was probably the best-known Episcopal rector in the United States.

The archway of this cozy inglenook off the first-floor library contained matching sunburst panels and was decorated above with incised hexagons. Dominating this intimate space was a simple, if not crude, fireplace composed of brick sides and slabs of brownstones that formed its shelves. On these shelves Brooks put objects and souvenirs he had received from friends or collected on his travels. This setting, then, was determined by experiences and personal choice rather than artistic rules. This was one of the rare private spaces illustrated in Artistic Houses on which contemporary decorative etiquette exerted little influence.

200. Drawing room, George W. Childs house, 2128 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; John McArthur, Jr., architect, 1869; destroyed by fire 1970. Though not well remembered today, Childs (May 12, 1829–February 3, 1894) was respected in the late nineteenth century as a responsible and benevolent millionaire. His story was one of the true fairy tales of American capitalism. He left school at 13, was an errand boy in a bookstore at 15 and the owner of a bookstore three years later. During the 1850s he became a partner in the publishing firm of Childs and Peterson and married his partner’s daughter, Emma Bouvier Peterson. In 1864 Childs purchased the ailing Public Ledger, made the necessary managerial and editorial changes and confirmed the newspaper’s recovery by erecting the magnificent Ledger Building in Philadelphia in 1867. Financially secure, he gave increasing attention to collecting rare books and letters, to hosting international dignitaries and to philanthropy.

In several respects this house was a modest version of A. T. Stewart’s palace (nos. 1–8), completed the same year in New York. Both had a marble exterior and were studiously detailed within. When completed, both were considered foremost examples of expensive interior decoration in their respective cities. This photograph shows the drawing room from the adjoining music room. The drawing-room floor was covered with an Aubusson carpet, the wainscoting was made of amaranth wood (not a commonly used material), the walls were covered with panels of crimson satin and the ceiling was decorated in fresco with papier-mâché relief. The mantel mirror, framed in satin-wood, was placed to reflect the lights of the chandelier and its Florentine glass pendants. At the end of the room was one of the world’s most expensive parlor clocks (Childs owned more than 50), a medal winner at the 1867 Parisian Exposition for which Childs had paid $6000, outbidding A. T. Stewart. Nine feet high and weighing approximately two tons, the clock consisted of a 4′-high base on which stood a silver figure of a woman holding a gold pendulum in her raised hand.

201. Dining room, George W. Childs house, 401 South Bryn Mawr Avenue, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania; John McArthur, Jr., architect, date unknown; standing but altered. Emma and George Childs owned two additional houses. Their summer home at Long Branch, New Jersey, was next to the summer house of Ulysses S. Grant. Their summer and weekend house at Bryn Mawr was a Queen Anne design called “Wootton.” Today this house serves St. Aloysius Academy. The dining room was comforting in scale, playful in its wallpaper frieze and table covering and warm in its mahogany paneling and beams—in effect, an interior suitable for the relatively relaxed summer life at a country seat.

202. Drawing room, George W. Childs house, Bryn Mawr. Compare this drawing room with the same family’s city drawing room. Here the ceiling is flat and quiet, encouraging the eye to look below. Even the pale wallpaper is relatively unobtrusive and emphasizes the stronger colors of the portieres. The room has been divided into three basic registers. The first includes the carpet, throw rug, chairs and divans (of blue and crimson plush), piano, table and fire opening, and extends to the top of the butternut wainscoting. Here the colors and textures are the strongest. Above this is a less demanding though more formal register that ends at the top of the rods over the doorways and the top of the mantelpiece. Finally, there are the flat, paler upper walls and frieze. This system has been reinforced by the small size and subdued themes of the paintings. On the far wall is a watercolor of a standing dragoon and his horse by Detaille.

203. Office, William M. Singerly, Philadelphia Record Building, 917–919 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Willis G. Hale, architect, 1880; demolished 1932. Singerly (December 27, 1832–February 27, 1898) was publisher of the Philadelphia Record and owner of the Record Publishing Company on Chestnut Street. He was twice married: to Pamelia Jones in 1854 and to Mary Ryan in 1872. In addition to his publishing activities, he served as president of the Chestnut Street National Bank, the Chestnut Savings Fund and Trust Company and the Singerly Pulp and Paper Mill.

With its fine furnishings and odd assortment of “authentic” works of art, this office suite looked more like a domestic than a commercial setting, and was probably included in Artistic Houses for this reason. This room of the suite was approximately 20′ from side to side and also from floor to ceiling. The sides visible in this photograph were filled with cabinets lined with sea-green plush and fronted with doors and mirrors of beveled glass. Below the cabinet on the left was a fireplace faced with Formosa marble and lined inside with Minton tiles. Opposite was a sink, also of Formosa marble. Clusters of turned columns accented the cabinets and framed the entranceway. The furniture was of wicker or black walnut with maroon leather. The simplified gasolier with two globes held an awkwardly attached electric wire that ran from the floor through the table lamp to bare bulbs. Silver, gold and turquoise blue were the colors chosen for this space. The frieze near the top of the room showed birds of paradise in ornate panels.

In this man’s world of late nineteenth-century American capitalism, most of the fine art glorified women. Right of center is a small marble, The Diver, by Odoardo Tabbacchi (1831–1905); the bronze statuette of a woman dancing with bells next to the entranceway is unidentified.