Oliver Ames was near the height of his political and business career when he erected one of the finest mansions in Boston. Built in 1882, the Ames residence occupies one of the city’s most prominent corners, Commonwealth and Massachusetts Avenues. Ames was born on February 4, 1831 in North Easton, Massachusetts, and died on October 22, 1895. His father, Oakes Ames, was a successful businessman who operated a shovel factory. Oliver combined educational activities at various academies and at Brown University with working in his father’s factory, where his physical labors included work at the shovel forges. In 1860 he married Anna Coffin Ray (1840–March 11, 1917) of Nantucket and fathered two sons and four daughters.

The pivotal event in Ames’s career came in 1873, when his father became implicated in the Crédit Mobilier scandal involving the unscrupulous sale of federal lands to Western railroads owned in part by him. The elder Ames, at the time a member of Congress, was censured by his associates for his role in the affair. Upon the death of Oakes Ames in 1873, Oliver inherited the responsibility of managing a vast railroad and industrial empire that was on the verge of financial collapse in the wake of the scandal. Pledging his own fortune, Oliver finally succeeded in liquidating his father’s debts and honoring all obligations. He once remarked, “If I could efface the record of that [Congressional] vote of censure, I would willingly bring my political life to a close.” This desire to redeem his father’s name morally and financially led him into politics. Though he was never elected to Congress, he was elected Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts in 1882 and served for four years before his election as Governor in 1886. Neither a distinguished public speaker nor a creative politician, Ames was a moderate who gained the respect of the electorate and the Bostonian business community. Clinging to his principles of free trade, he retired from politics a few years after his third term as governor. As a vocal opponent of the high tariffs that were supported by his own party, Ames was denied a seat at the 1892 Republican Convention.

The interest of Oliver Ames in regaining the respect of the public in the wake of his father’s censure extended not only to the fields of politics and business, but also to architecture. In conjunction with his brother, Oakes A. Ames, he erected the Ames Memorial Town Hall (North Easton, Massachusetts; H. H. Richardson, architect; 1879–81) in memory of his father. His fine mansion on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston may also have been inspired by the same sentiment. Sheldon described it as “one of the largest and costliest of the many fine residences which line both sides of Commonwealth Avenue.”

Ames and his brother employed Henry H. Richardson (1838–1886) to design a number of buildings on their behalf, such as the Ames Building (1882–83) in Boston, the Ames Memorial Library (1877–79) in North Easton and the Ames Monument (1879) in Wyoming. These buildings for the Ames family were typically Richardsonian—rock-faced exteriors with simplified Romanesque styling. Richardson was initially employed by Ames to prepare the design for his Boston mansion. As part of the design, Richardson proposed a drawing room in “pearly white” and gold, with ultramarine walls. This decorating scheme was retained in the drawing room of the final version even though Richardson was replaced by the lesser-known Boston architect Carl Fehmer.

Resolute below, the finished house expressed materially a confidence that was apparent in the struggle of Ames to clear his family name. However, the weight and serious mien of the lower floors were relieved by the picturesque roof level, where overscaled dormers and prominent chimneys made a lighter public statement. Fehmer utilized a brownstone surface composed of smooth-cut rectangular blocks accented by classical ornamentation concentrated around the window and door openings and on a broad horizontal band between the first and second floors. It is unknown why Ames replaced Richardson with Fehmer, although it is possible that the widely traveled and well-educated Ames desired greater archaeological accuracy and a higher degree of ornamentation than was present in the plans by Richardson. This trend toward greater reliance on stricter interpretation of European precedent in architecture and decorative arts was to become more prevalent later in the decade.

33. Hall, Oliver Ames house, 355 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts; Carl Fehmer, architect, 1882; standing. The house is entered through a vestibule which, in the 1880s, was lined with statuary and richly colored marble. These figures were grouped beneath a vaulted stained-glass ceiling of softly tinted colors. The hall in this period was finished with cherry woodwork and colored in soft gray-blue. A large, ornately carved wood screen, which appears in the left foreground, partially divides this enormous hall, somewhat lessening the dramatic scale of the room. The center of the attention in this view is the large fireplace placed between two windows. Above the fire opening was a carved arch containing relief figures and at the sides peculiar columns, classical below with unclassical caryatids above, supporting the high mantel. While the basic character of this space is Renaissance-inspired, the vigorous ornamentation, with its human, animal and composite figures, lends a medieval flavor.

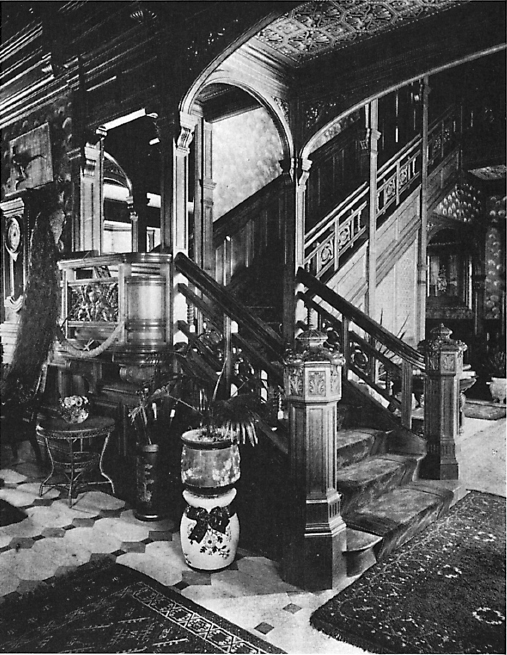

34. Hall, Oliver Ames house. This view shows the large stairway that winds to the second floor beneath an enormous stained-glass dome in strong colors. On the first landing is a painting by Jean-Gustave Jacquet, The First at the Summit. At an auction of the Ames estate held at the American Art Galleries in 1919, this painting was sold for $425. The major spaces on the first floor open onto this great oak hall—the library, music room, reception room and dining room. The drawing room was not pictured in this publication, though a period photograph appears in The Tasteful Interlude (1981) by William Seale.

35. Library, Oliver Ames house. This room has a more refined elegance than the animated decorations of the hall. It was decorated by C. H. George of New York with a dominant color scheme in a soft greenish hue with contrasting deep red mahogany woodwork. The walls are covered with a copy of old Venetian silk in tones of green and brown. This green was also used for the hangings and to upholster the furniture. Like other parts of this room, the finely painted embossed ceiling, arranged in octagonal sections, was created to be impressive to the eye without being distracting. Judging from the shelves and available work area, the books in this library were used as much for decorative value as for their intellectual stimulation. Although the windows of this space provided good interior light, the light could be reduced by drawing the hangings. Stained glass fills the clerestory panels.

Examples of the valuable collection of paintings and art objects that Ames collected are visible in this room. The collection was liquidated in 1919 for a total value of almost $60,000. Although he hung in his library paintings by popular European artists, among them Mihaly Munkacsy (1844–1900), J.J. Lefebvre (1836–1911), Charles Landelle (1812–1908) and C. E. Delort (1841–1895), the canvases that brought the highest bids were two by the American landscape painter George Inness (1825–1894). Opening directly from the library, but not visible in this photograph, is the music room, decorated in golden plush drapery and gilded woodwork.

36, 37. Dining room, Oliver Ames house. This large room spans the entire breadth of the house at its rear, separating the formal rooms of the front section from the extensive rear servants’ wing. The room is finished throughout with oak woodwork. The paneled wood ceiling is supported at its edges by large caryatids depicting characters from mythology. Looking toward the west, we see five of the seven windows in this spacious room and matching niches containing identical vases, while toward the east we see an enormous sideboard of oak flanked by similar niches. To complement the oak color, the wall of silk tapestry was dull blue and the hangings a warm madder red. Polished brass fittings sparkled in the fireplace. Also of oak, the tables and chairs were created in an early German Reniassance style.

The bedrooms, located on the upper floor, were ornamented in a variety of colors. In its dazzling decor and opulence, this house is symbolic of the wealth and prestige attained by Oliver Ames and of his triumph over his family disgrace. The decoration of these interiors also displays quite dramatically some important concepts in late nineteenth-century American interiors: the implication of age, created by darkened wood and ornamental motifs inspired by medieval and early Renaissance styles; the ever-present clutter of small decorative items that leaves few voids; and the mixture of styles from room to room and even within each room. Because the owner evidently took such a direct role in the shaping of this residence, as indicated in the selection of the architect and involvement with various decorating firms, the house was an informative document of Bostonian wealth and social-political power in the early 1880s.

The Oliver Ames house was converted into luxury office space in the course of a 1981 renovation, resulting in the restoration of the major rooms of the first floor and the creation of additional office space in the basement and attic—a total of six floors of offices. Using federal income-tax incentives for historic preservation, restorers have reclaimed the stained-glass windows, gilded ceilings, wood paneling and grand stairway. The Ames house is among the minority of houses in this book that survives in a respectable state of preservation.

38. Library, Rudolph Ellis house, 2113 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Furness and Hewitt, architects, ca., 1874; standing. The house of Rudolph Ellis (November 20, 1837–September 22, 1915) and his wife, Philadelphia native Helen Struthers (whom he married April 26, 1866) was either built or remodeled by Furness and Hewitt about 1874. In 1889 the house was remodeled again for R. Winder Johnson by Furness, Evans and Co. Ellis returned to Philadelphia after service as a captain in the Civil War. He formed R. Ellis and Co., a brokerage firm. In time he held several directorships, including one on the board of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and in 1901 became president of the Fidelity Trust Co. of Philadelphia. In his last years he moved to suburban Philadelphia, serving as a trustee of Radnor Township and president of the Radnor Hunt Club.

Judging from the pieces on the shelves around the mantel, the Ellis bric-a-brac was fashionable but not exceptional, consisting of Japanese ceramics, bronze statues, a metal clock, a brass container. However, the ceiling of the library was unique. Apparently, it was arranged in squares outlined in oak blocks. The field of each square was highlighted in crimson, the same color used for the portieres and the window draperies. Ceilings of such height and decorative complexity were not common in domestic libraries because these rooms usually were designed to appear intimate and peaceful. In the ideal library the books were expected to be the focus of the decorative scheme; here they were not. On the other hand, we could conclude from the manner in which they have been stacked on the shelves that these owners used them more frequently than most whose libraries appeared in Artistic Houses.

The woodwork around the mantel, like that of the ceiling, was eye-catching and complicated. Lathe-turned, inlaid supports, resting on plinths, not only stabilize the mantel but also pass through it to support a higher shelf at each side of the mirror. Were these supposed to be the stalagmites complementing the stalactites in a ball-and-rod motif that hung from the blocks of the ceiling and secured the overmantel shelf? In the middle of this intricate support system was a dark oasis, a plate-glass mirror backed by velvet rather than the usual quicksilver. This room probably was much lighter than it appears in this picture because the drapes have been drawn to aid photography.

39. Hall, Henry M. Flagler house, Edgewater Point, Mamaroneck, New York; architect unknown, date unknown; destroyed by fire 1924. In its obituary notice, the New York Times referred to Flagler (January 2, 1830–May 20, 1913) as “one of the world’s richest men.” His oil-refinery partnership with the Rockefeller brothers in Cleveland was reorganized as the Standard Oil Company in 1870. Although Flagler remained an officer of Standard Oil until 1908, he concentrated his energies after the mid-1880s on the development of Florida, building the hotels and railroads that helped to transform the state into a winter resort.

He rented this house at Mamaroneck in the summer of 1881 and purchased it the following year for $125,000. He may have rented the house as a means of keeping his family together after Mary, his wife of 28 years, died in May of 1881. Two years later he married Ida Shourds, but their relationship deteriorated and in 1897 she was committed to a mental sanatorium. A week after he obtained a divorce on grounds of insanity in August 1901, he married 34-year-old Lilly Kenan.

According to biographer S. Walter Martin, “By January 2, 1885, Flagler had spent $330,992.51 on the Mamaroneck property. The house was completely renovated inside and out. New fixtures were installed throughout the dwelling and attractive furniture was bought. Even the chandeliers were according to Flagler’s own ideas.” The appearance of the inlaid wood floor suggests that this part of the house had been renovated when this photograph was taken.

The hall of this 40-room summer retreat was probably large with a high ceiling and ample natural lighting. It is a good example of American open planning of the early 1880s, which often resulted in vistas passing through linked rooms of the main floor and even vertical perspectives between levels. The carved newel posts, supports and cornice were designed in a simplified Renaissance style. Less conservative was the balustrade of the stairs with its carved panels and truncated, lathe-turned elements. The landing of this staircase was unusual. A large mirror, reflecting the space in front of it, contributed to the spatial complexity of the hall. The area of the landing was large enough to provide room for a rocking chair. The outside face of this peculiar alcove contained a complicated carving of two griffins facing a central urn. From a hook or nail above, someone has hung a carved elephant tusk that cradles a dried starfish. Another odd feature is the block of wood, attached to the railing by a common rope, that balances the stuffed peacock.

40. Dining room, Julia T. Harper house, 4 Gramercy Park West, New York, New York; architect unknown, 1847; standing. Julia Thorne (1821–1902) married James Harper (April 13, 1795–March 27, 1869) in 1848, a year after his first wife of 24 years, Maria Arcularius, died. Their residence overlooked Gramercy Park, one of two fenced parks in New York City to which only the owners of surrounding houses had keys. In front of the Harper house were two wrought-iron lampposts, mayor’s lamps—symbols reminding pedestrians that he had held the highest office in the city (1844–45). The lamps, as well as the iron portico of the porch, still stand in front of the relatively unchanged four-story exterior.

After an apprenticeship to a printer, James, with a younger brother, formed the printing firm of J. & J. Harper in 1817. In 1833 it became Harper & Brothers, one of the most successful publishing houses in the United States in the nineteenth century. Historians credit James for conceiving of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, which appeared in 1850. Mrs. Harper was not philanthropically active after his death, in part because she was an invalid for most of her life.

In 1879 her son, James Thorne Harper, and his wife commissioned Stanford White to create this dining room at the rear of the house. Solid and unpretentious despite an abundance of whatnots, it attracted Sheldon by its moderation and cohesiveness. “A fine sense of repose belongs to surroundings in perfect accord with the desires of a cultivated taste, and full of evidences of a sensitive observation at the disposal of a trained and knowing hand.” The principal woods—mahogany for the wainscoting and oak for the paneled ceiling—were choices often seen in elegant dining rooms of the period. The embossed leather, covering the wall between the wainscoting and ceiling, was another material considered quite proper though also quite expensive. This leather was a discreet blue-green, highlighted with touches of bronze paint. Like the walls, the chairs were mahogany padded with embossed leather. Sheldon appreciated such a carefully coordinated unit: “Nothing glares; nothing stares.” The dark propriety of this dining room was distinctly unlike the rooms of the Tiffany (nos. 13–16) and Colman (no. 29) houses, in which the decorative means were varied and competitive and their impact less subdued and stable.

On the other hand, the Harper dining room was not featureless. Above the table the splendid chandelier of cut glass that concealed the gas jets was set in a coved octagonal recess. At the side wall were windows of intricately leaded glass, partially veiled by the thin curtains. Warm, serious and protective, this dining room was a formal expression of the sentiment cut in the marble over the fire opening, “Tis Home Where The Hearth Is.”

41. Library, Clara Jessup Moore house, 510 South Broad Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Charles M. Burns, architect, 1875; demolished 1958. Despite Clara Jessup Moore’s (February 16, 1824–January 5, 1899) reputation as a writer, the Philadelphia Directory of 1883, reflecting the period’s reluctance to credit women as professionals, identified her as a “widow” living at 510 South Broad Street. Granted, this information was true. Her husband, Bloomfield Haines Moore, the owner of Jessup & Moore, a paper-manufacturing firm, had died on July 5, 1878, leaving her this house in a French château style that King’s Views of Philadelphia, as late as 1902, described as “unquestionably the handsomest residence on South Broad Street and one of the finest in the city.”

The couple were married on October 27, 1842. They raised three children, one of whom, Ella, became the Countess von Rosen, wife of the chamberlain of the King of Sweden. Clara Jessup Moore wrote on social etiquette—The Young Lady’s Friend (1873), Sensible Etiquette of the Best Society, Customs, Manners, Morals and Home Culture (1878), Social Ethics and Society Duties (1892)—several novels, (including On Dangerous Ground of 1876, which enjoyed many editions and was translated into French and Swedish), books for children (among them Master Jacky’s Holidays, which went through more than 20 editions), poems and even The Role of Doctor and Nurse in Caring for Insanity (1881). She wrote under the pseudonyms Bloomfield-Moore, Clara Moreton and Mrs. N. O. Ward.

Number 510 South Broad Street was an address closely associated with art collecting in Philadelphia. In 1882 Clara Jessup Moore gave many pieces of furniture, pottery, textiles and other types of decorative art to the Pennsylvania Museum, later the Philadelphia Museum. In 1883 she donated 100 paintings from her collection and in 1899 gave 20 more. Two other collectors, Francis Thomas Sully Darley and John G. Johnson, subsequently lived in the house.

Where Clara Jessup Moore wrote is not known; here the library does not appear to contain any writing equipment. The room certainly was a distinctive space, one independent of contemporary views of how to furnish interiors correctly. The high ceiling confirms the approximate date of the house, 1870–75. The mantelpiece was gigantic, imaginatively designed and plastically aggressive—somewhat similar to a few exteriors in Philadelphia designed by Frank Furness. A veritable medieval bestiary haunted the gable of the overmantel, while below Burns transformed familiar elements of old architecture into peculiarly modern shapes. So strong was the wooden frame of the fireplace that it overwhelmed the decorative contributions of shelf objects and figured andirons. Through the window at the right, unusually broad for an interior window in these houses, we can see the drapery, chandelier and exterior window of the adjacent drawing room. The marble statue of Cupid, seen from the rear, was in the drawing room; in front of the glass were two bronze figures representing Science Guiding Industry. Despite these architectural peculiarities, the room looked more comfortable than staged. There were Chinese porcelain fishbowls serving as planters on either side of the window, a Chinese-silk fire screen, ancestral pictures on the walls, black-walnut bookcases and modest furniture.

42. Dining room, Clara Jessup Moore house. The Moores had collected much of their furniture during trips to Europe. Some of their finest pieces were displayed in the dining room—the sideboard carved in high relief in the left corner and an oak cabinet, also carved, opposite it. This cabinet was filled with choice pieces of Capodimonte, porcelains initially manufactured in the royal palace of Capodimonte under the patronage of Charles III of Naples in the mid-eighteenth-century. At the immediate right was a mantel with an oval mirror, the frame also in high relief. Through the doorway at the rear can be seen the picture gallery, which may have been an addition to the original house.

43. Hall, Clara Jessup Moore house. To the left of the hall were the library and the drawing room, directly ahead the dining room and picture gallery, and to the right the stairway and a front reception room. The hall was an exhibition area, a preliminary space that announced the finer attractions beyond. The exhibition consisted of an assortment of chairs on which people seldom sat, examples of the owners’ porcelains and inlaid tables, a collection of Moorish arms over the arch—proof that the Moores had traveled in exotic lands—and copies of the Venus de Milo, Augustus of Primaporta, and Nydia by Randolph Rogers (also seen in the Stewart home, no. 1). The most unexpected elements of this stylistically eclectic setting were the pre-Art Nouveau flowers of the stairwall.