Field (August 18, 1835–January 16, 1906) hired the rising Richard Morris Hunt of New York to design this house in 1871, just before the outbreak of the Great Chicago Fire. Untouched by the conflagration, construction continued until the structure was completed in 1873, at a cost of approximately $250,000. At that time Field and Levi S. Leiter were partners in Field, Leiter and Company, Chicago’s most successful dry-goods firm. In 1881, when the annual volume had reached $25 million, Field encouraged Leiter to retire and renamed the business Marshall Field & Co.

He had been married to Nannie Douglas Scott for ten years when they moved into their new house on Prairie Avenue. This residential street near the Loop—Field walked to work—attracted millionaires. Until the 1890s, when they began to move to more fashionable locations, the residents were known as the “Prairie Avenue Set.” The Fields had two children, in whose honor they invited 500 guests to their famed Mikado Ball in January 1886, and were active socially, although their marriage was not the kind that poets write about. She died in 1896, and he remarried a widowed friend, Mrs. Delia Spencer Caton, in 1905, shortly before he died of pneumonia. The house was bequeathed to the Association of Arts and Industries in 1937 to be used as a school of industrial arts. After the building was remodeled, the school opened under the name of the New Bauhaus, directed by László Moholy-Nagy, who had worked with Walter Gropius at the original Bauhaus in Germany. This venture failed financially, and the school was closed.

Compared to the house erected in New York City by his dry-goods counterpart Alexander T. Stewart (nos. 1–8), Field’s town house was modest. It was certainly much less expensive, smaller, was finished in brick and sandstone rather than marble, and though designed in the popular Second Empire Style, it did not challenge the art world as Stewart’s palace had. The principal west facade comprised a high basement, two conservatively ornamented floors and a tall but uninteresting mansard attic. The house was neither gracefully designed nor expressive of a clear artistic idea. Visually more attractive was the asymmetrical south facade, containing the glassed conservatory.

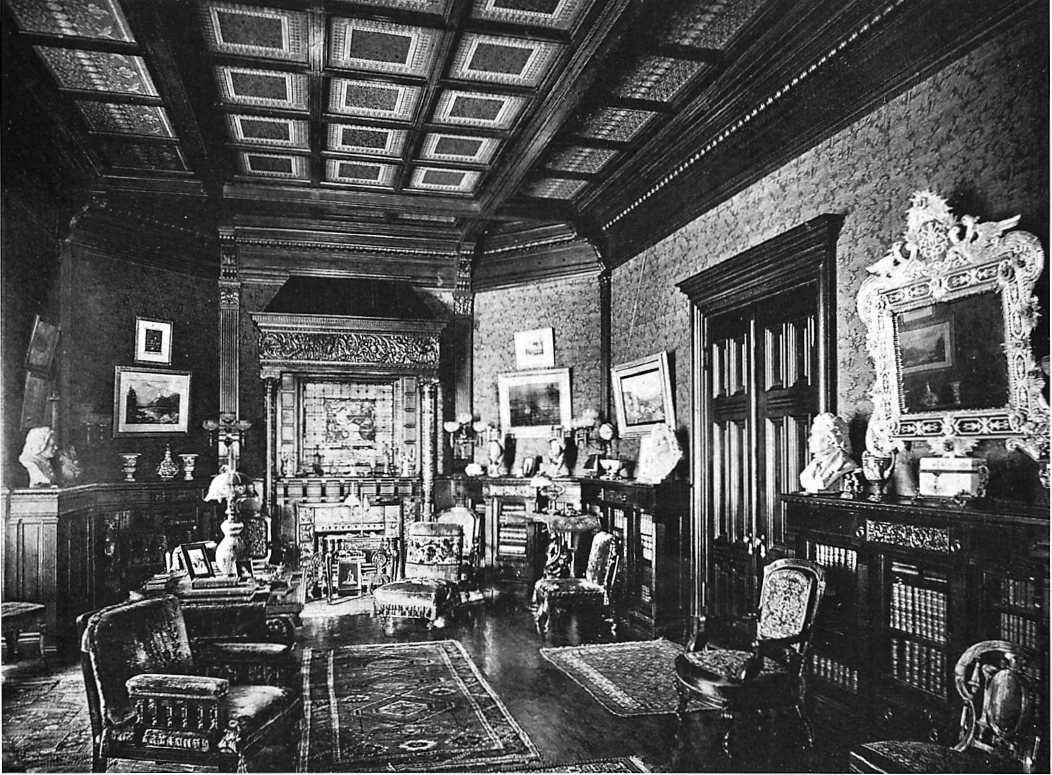

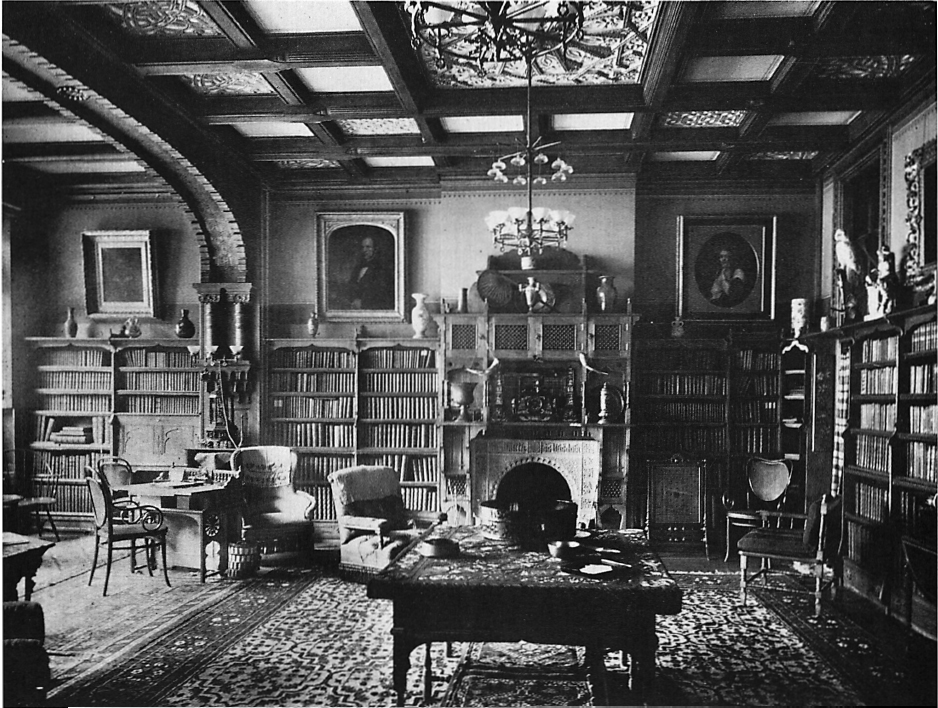

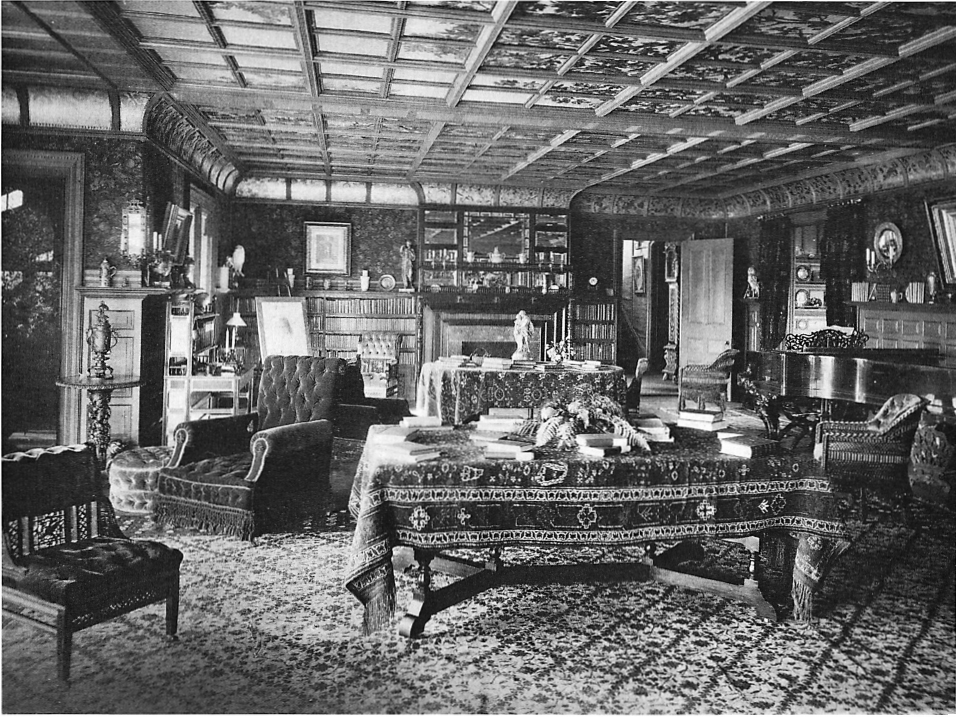

55. Library, Marshall Field house, 1905 Prairie Avenue, Chicago, Illinois; Richard Morris Hunt, architect, 1871–73; demolished 1955. Though this criticism may be unfair because there is no clear evidence to support it, this library seems to be composed of compatible objects that have been chosen and collected without a workable definition of a library to guide these choices. In other words, the inventory is there, but the parts do not mesh easily into a unit that reflects definable personal ideas and a specific functional goal. Perhaps a safer way to state this is to argue that Hunt designed a room with character that the Fields confused.

There is considerable power and fine craftsmanship in the double doors to the hall, in the cornice, ceiling and built-in bookcases that serve also as the wainscoting of the room. There are also focal points in the room—the bay window opposite the double doors to the hall and the elaborate fireplace opposite the doors to the drawing room. But the furniture has been placed without concern for the intentions of the designer. Ineffective for conversation, the chairs at the right also suggest that the glass doors of the bookcases were seldom opened. The closeness of the table to the fireplace may mean that logs were seldom burned. This table and its lamp obscure the beautiful tiles around the fire opening, while the containers and candelabra on the mantel shelf obstruct our view of the delicate stained-glass window behind. This apparent stress on the inclusion of items without much concern for their functional and artistic integration raises the possibility that this room was used primarily for display.

The Fields owned paintings by Millet, Schreyer and Meissonier, among others, but none of the paintings in the library can be identified with certainty.

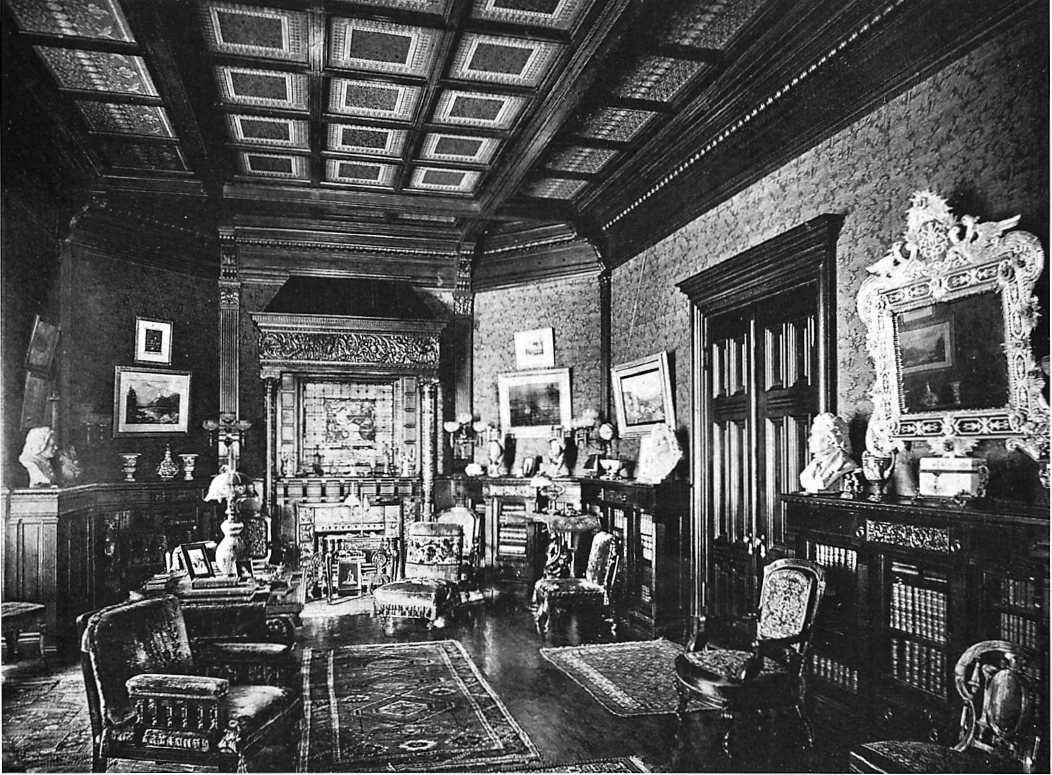

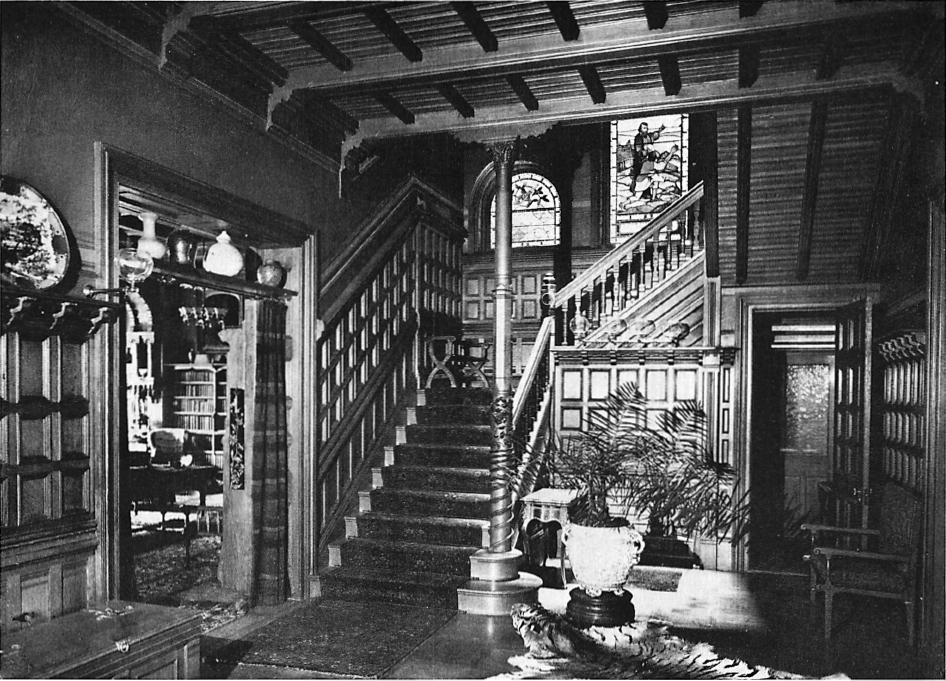

56. Hall, Marshall Field house. From Prairie Avenue granite steps led to the main door, which opened into the vestibule, with its marble floor and mahogany woodwork, and then into this peculiar hall, cut through the center of the house. On the left of the hall were the drawing room, decorated as a French salon of the seventeenth century, and behind it the library. On the right side was the reception room and behind it a short passageway that led from the bulge in the center of the hall to the conservatory on the south side.

In an obvious attempt to counteract the length and emptiness of this hall and also to deemphasize its traffic function, the center of this space was widened. Domestic touches—the hearth, rug and chairs—were added, but the result looked contrived and not very inviting. Furthermore, the graceful stairway at the end of the hall, bathed by light from stained-glass windows above and faced below by imaginatively designed woodwork, a stairway that deserved an uninterrupted view, was diminished by the chandelier and the projecting furniture and heavily articulated entranceway. There is so much friction between this wide space in the hall and its objects that we may wonder if the photographer did not take the picture after the furniture companies had disgorged their wares and before these pieces had been carried to their intended rooms.

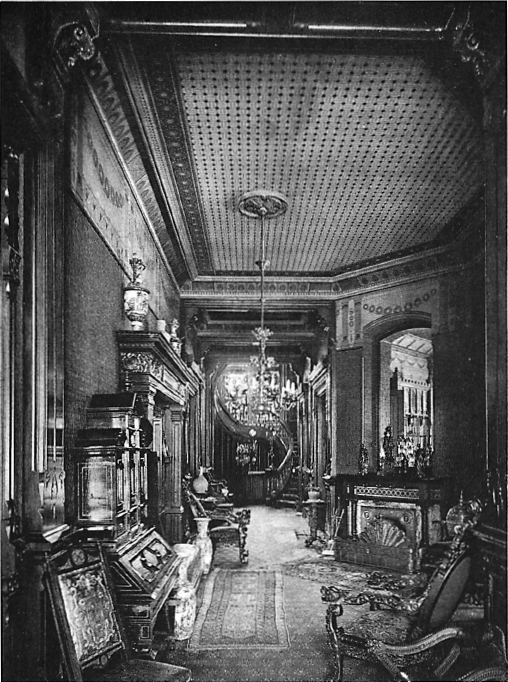

57. Hall, Asa P. Potter house, Nantasket Beach, Massachusetts; architect unknown, date unknown; demolished. What a contrast between this hall and the hall of the Field mansion! In the latter the potentially intriguing space was given character through very respectable pieces and by fine details such as those on the embossed walls or on the frescoed frieze and ceiling. Because these specific objects invited individual attention, it was impossible to move from the vestibule to the stairs without engaging in a series of acknowledgments. At the Potter house, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, the great space of the hall was more impressive than anything in it. The planners and owners did not clutter it with furniture and kept its structural details to a minimum. In the hall of the Field house visitors understood that, interrupted as it was, they had to pass through it to participate in family life. In the Potter hall visitors were more likely to stand still, watching for signs of family activity on three levels. These differences were encouraged undoubtedly by the differences in purpose and location of the two houses. One was a solidly built city residence in Chicago’s most prestigious neighborhood, the other a summer house of wood overlooking the shore.

The Potters lived at 244 Commonwealth Avenue in Boston and relaxed in this house at Nantasket Beach. Asa P. Potter was born in 1838 and died on June 17, 1929; Mrs. Potter died on February 14, 1916. They had two daughters and four sons. Beginning in the paper business, he shifted to banking and became president of the Maverick National Bank of Boston.

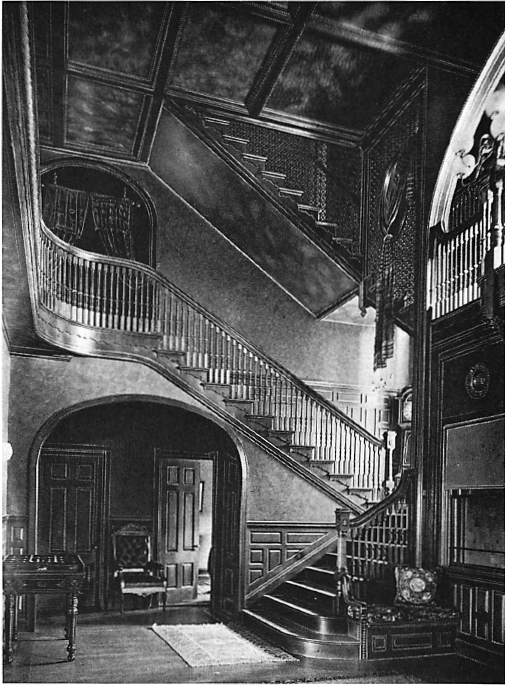

58. Hall and stairway, Frederick F. Thompson house, 283 Madison Avenue, New York, New York; McKim, Mead and Bigelow, architects; 1879–81, demolished. A founder and longtime director of the 1 st National Bank of New York City, Frederick Ferris Thompson (June 2, 1836–April 10, 1899) was a banker throughout most of his adult life. In 1857 he married Mary Clark (December 27, 1835–July 28, 1923), the daughter of the governor of New York. Thompson was a gregarious and intellectually lively individual who gave generously to educational institutions (Williams College, Vassar College, Columbia Teachers College) and to organizations encouraging the arts and the study of folklore, geography, archaeology and photography. He operated his own printing press, publishing a small paper dedicated to the advancement of photography. After his death, Mrs. Thompson gave money to Williams for a chapel and to Vassar for a library.

The house cost approximately $66,000. Ten steps from the sidewalk led to a high first floor, permitting a well-lighted basement that contained a billiard room and a rare bowling alley erected over brick-arch construction to limit noise. There were many conveniences and safeguards built into the house at the request of the Thompsons. In one of the two vestibules was an exposed steam coil to warm the cold feet of waiting telegraph boys. The inner vestibule had a concealed door that admitted those familiar with the house to use the toilet facilities on the second floor before making their formal entrance down the main stairway of the hall. There was also a hydraulic elevator with several safeguards.

Though Montgomery Schuyler (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, September 1883) did not think the exterior noticeable, the main hall was unquestionably distinctive. Completed by Stanford White after he replaced Bigelow as third partner of the firm in September 1879, it was large (38′ × 18′) for a New York town house and, in character, reminiscent of halls this firm designed for country houses in the early 1880s. Used as a connecting link, it was sparsely furnished. European visitors were often surprised by such internal openness as the inviting entrance to the library at the left, accustomed as they were to compartmentalized entering halls that protected the privacy of the family. In the same spirit, the route to the upper floors was open and clearly marked; in fact, the visitor was challenged to climb to the summit by the stained-glass windows illustrating Pilgrim’s Progress.

Madison Avenue entrance (right).

59. Hall, Frederick F. Thompson house. The recessed fireplace under the elliptical arch on dwarfed columns was on the north side of this hall, which paralleled Madison Avenue. The scene carved on the Caen stone mantel frieze depicts calla lilies and ferns; the panels above have signs of the Zodiac: Pisces, Aries and Scorpio. The right angles of these mantel panels were repeated in the small square oak panels of the walls and the ceiling of the same wood. Two brass ewers were the only objects on the short mantel shelf. In this warm but well-disciplined setting, the glass globes of the wall sconces look exceptionally delicate. At the foot of the stairs was an unexpected piece of contrasting decoration, a carved plant that wrapped around the column with the freedom of a fully developed Art Nouveau motif.

60. Library, Frederick F. Thompson house. Among the libraries illustrated in these photographs, this was one of the largest and, judging from the setting, one of the most functional and frequently used. The room, 30′ square, held approximately 3000 volumes stacked on maple shelves, some equipped with slides to support the book being consulted. There were enough tables and flat surfaces for work. The unmatched furniture—the slat-back Windsor armchair, bentwood chairs with cane backing and well-used stuffed armchairs—was not selected primarily for display. Similarly, the bric-a-brac was mixed and not obtrusive. Above the shelves, 7½′ high, the wall space was painted a neutral color and hung with portraits. The Moorish flavor of the room came mainly from the arabesques of stucco in some of the ceiling panels and the tile designs painted on the underside of the wooden divider. As in every major room of the house, there was a ventilator in the center of the ceiling to circulate the air and to remove cigar smoke and gas leaking from the chandeliers.

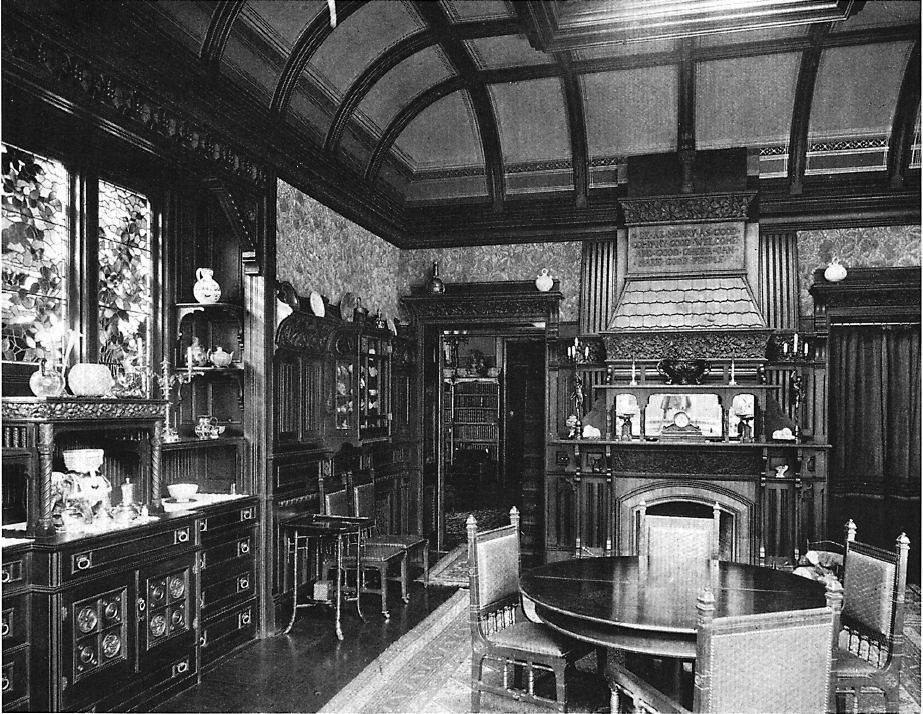

61. Dining room, Frederick F. Thompson house. The principal rooms of these houses of the early 1880s were often designed and furnished to look distinctly different from each other. In the Thompson house, dissimilarities were particularly striking, as if each space had been designed by a different hand. Since the architects were paid approximately $6500 for interior furnishings, they may have been responsible for finishing these rooms.

The dining room was not timidly designed; it contained features that could have affected the whole negatively if they had not been skillfully controlled. The space could have been overwhelmed by the woodwork that rose to the cornice above the sideboard and almost to the height of the doors in other sections. To avoid this, the lively stained-glass windows, depicting birds, trees and flowers, counteracted the prominent sideboard below. At the sides of these windows were thin, curving shelves that also counteracted the weight of the sideboard.

To create plate shelves above the panels and above the lintels of the doors, the designers projected the frieze instead of allowing it to remain flat, adding to the possibility that the woodwork was too high and too heavy for the room. On the other hand, the floral pattern of this projecting frieze may have added more energy than weight to these sections. The same rippling effect is apparent on some registers of the terra-cotta overmantel. This floral pattern connected the woodwork and the terra-cotta to the plant life of the stained-glass window and also to the textured paper below the cornice. Furthermore, the profile of the supporting plate and pot shelves announced the coved ceiling, where the architects knew better than to include the heavy timbers of ancient banqueting halls. Instead, the ceiling was divided by relatively light strips of mahogany. The higher ceiling permitted higher wall decoration. Above the table was a square stained-glass skylight.

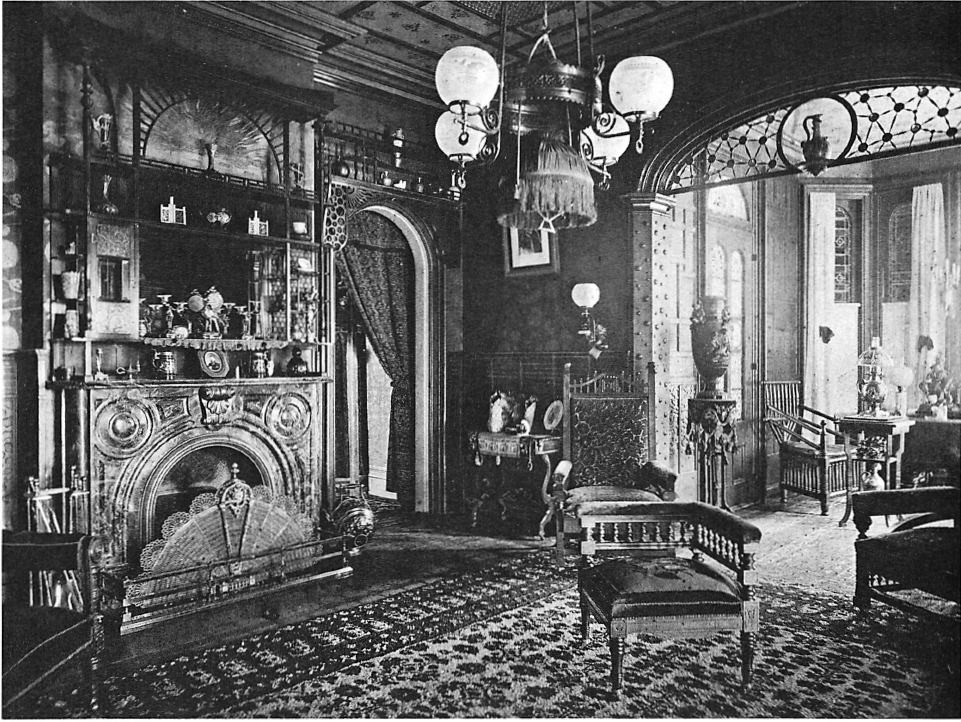

62. Dining room and conservatory, Frederick F. Thompson house. The woodwork of the dining room would have been more oppressive without the grand conservatory bay. Conservatories were commonly attached to dining rooms because plants gave off a pleasant fragrance that could also combat odors from the kitchens nearby. (Some architectural writers and arbiters of etiquette warned that prolonged exposure to the smells generated by plants could adversely affect guests. Consequently, the opening between dining room and conservatory was usually much smaller than it was here, or could be closed off.) From the evidence of this photograph, the dining room could not be sealed off from the conservatory. The main feature of this large conservatory, framed in brass, was its centrally located fountain.

63. Drawing room, Frederick F. Thompson house. Unlike most of the drawing rooms in this series, the walls and ceiling of the one in the Thompson house were treated as flat, neutral areas that set off the heavy coved cornice above and the paneled dado below. Except for the border lines and geometric designs in the corners, the buff ceiling was plain. The walls, painted a dull Indian red to complement the red cherrywood of the mantel, furniture and window trim, provided a suitable background for the paintings and Chinese embroidery that hung from the picture rail. Among the few wealthy New Yorkers who did not concentrate on French academic painting, the Thompsons had a small but respectable collection of works by Americans (Alexander Wyant, William Hart, John Kensett, Emanuel Leutze). Over the mantel is Venice, by Sanford R. Gifford (1823–1880).

The unifying cornice was composed of bronze panels depicting sunflowers and tiger lilies in relief. Strips of bamboo marked the panels of the dado, and bamboo was also used in the decoration of the mantel. Related stickwork appeared in the Japanese Revival sidechairs and in the cabinet in the right corner. This open and movable cabinet held prized small pieces which in most of the living rooms of Artistic Houses would have been displayed on fixed shelves attached to the fireplace. At the far left is another arrangement not seen often in these photographs, the bay filled with planters and the rod-and-curtain system that could separate this section from the main part of the room.

64. Library, Mariana Arnot Ogden house, Fordham Heights, New York, New York; Calvert Vaux, architect, ca. 1855; demolished. Following her husband’s death in 1877, after only two years of marriage, Mrs. Ogden managed “Boscobel” (beautiful wood) and its exquisite grounds until the relentless expansion of New York City transformed this area. Once a paradise of unusual trees—linden, weeping ash, purple beech, catalpa, cypress and Austrian, Weymouth and Cembra pines—this estate became an untenable oasis after the nearby Washington Bridge over the Harlem River opened in March 1889. The house, constructed of stone quarried on the site, was built for another family. William Ogden (June 15, 1805–August 3, 1877) purchased the property in the spring of 1866 but did not spend much time there until his marriage on February 9, 1875, four years after he moved to New York following the Great Chicago Fire. As the first mayor of Chicago, he was more closely tied to the first four decades of that city than any other single person.

Evidence suggests that this room was planned as the drawing room and the drawing room as the library. If true, this would explain its appearance, atypical of separate domestic libraries in the early 1880s, which would have been smaller, more intimate in character and less formal in decoration. The ceiling was tightly frescoed in a geometric pattern, the ebony jambs and lintels of the openings were unusually triumphal and the hangings and wallpaper smacked of “good taste.” On the other hand, the furniture, light and movable, made the room appear less formidable than its walls and ceiling implied it should be. The room was probably more important as a spatial extension of the drawing room than as a functioning library.

65. Drawing room, William F. Havemeyer house, 86 Harrison Street, East Orange, New Jersey; architect unknown, ca. 1871–78; demolished 1960s. William F. Havemeyer, Jr., (March 31, 1850–September 7, 1913) was born in New York, married Josephine L. Harmon in 1876 and began his career with the Havemeyer Sugar Refining Co. He retired from the sugar business in 1889 but continued to be active in banking. As a collector, Havemeyer concentrated on second-level American painters. He later concentrated on another hobby, collecting George Washington memorabilia.

The Havemeyer drawing room was not a memorable interior, despite its recent decoration by Roux and Co. of New York. Although it was finished in chestnut and mahogany with fretwork panels on the ceiling and Japanese paper of armor designs on red for the walls, and although much effort had been spent on the fireplace and overmantel—the peculiar coal scuttle on the left, the Victorian fan screen that echoed the rising-sun motif at the top, and the numerous display shelves in the middle—the room lacked distinctiveness and focus.

66. Drawing room, Knight D. Cheney house, 50 Forest Street, South Manchester, Connecticut; architect unknown, ca. 1860; standing but altered. This drawing room was one of the largest and most expensive included by Sheldon. It consumed space as if it were unlimited and cheap, in the manner of the great living halls that such architects as McKim, Mead and White created at the center of their resort houses of these years. Like those halls, this encouraged varied functions without appearing to be subdivided into obvious sections. Its appearance of unity was achieved by the fixed height of the wainscoting, the mantel shelf and bookshelves, and by the continuous wall covering of leather and the coved frieze above. Its appearance of breadth was due, in part, to the mirror of the mantelpiece, the vast carpet and the beams of the hand-painted ceiling that led the eye to the edges. Its appearance of comfort owed much to the softness of the upholstery, such as the Turkish frame armchair and ottoman at the left, the generous table coverings and the carpet.

The beautiful fabrics and coverings of this room were probably influenced by the owners’ business activities. Knight D. Cheney (October 9, 1837–August 13, 1907) became in 1876 a director of Cheney Brothers of Hartford and South Manchester, Connecticut, pacesetters of the American silk industry. In 1894 he became the firm’s president. On June 4, 1862, he married Ednah Dow Smith of Peterborough, New Hampshire. With 11 children, the Cheneys probably needed this family space.

The house was built as a three-story clapboard structure; the renovation of 1878–80 is attributed locally to Henry Hobson Richardson.