H. VICTOR NEWCOMB HOUSE, ELBERON

This house attracted much attention in the 1880s and has continued to appeal to later generations of architectural critics. Bruce Price, an architect and contemporary of McKim, Mead and White, described the first time he saw the Newcomb house (Scribner’s Magazine, July 1890): “I was driving from Sea Girt to Long Branch at the time, and, unaware of its existence, came suddenly upon it. The whole scheme, form, and treatment of the house were new to me, and I looked upon it with mingled feelings of surprise and pleasure.” Price emphasized new treatment and his emotional response. He was referring to the shingles that covered the asymmetrical exterior and bound the centrifugally oriented volumes within. It was, he thought, “the forerunner” of the shingle houses that gave both character and coherence to American domestic work of the early 1880s.

But Price was also probably delighted by the broad, sloping foreground of grass, the blue-gray background of sky and sea and the lively, unpretentious and imaginatively composed work of art in the middle. He may also have been responsive to the firm’s ability to convey “both-and” while avoiding “either-or”—asymmetry without imbalance, expansiveness without loss of center, activity without confusion. Mariana Van Rensselaer (The Century Magazine, June 1886) commented on this resolution of opposites in the Newcomb design: “A very just medium has been struck, I think, between that dignity which would have been too dignified for the environment and that utter simplicity which would have been out of character with the interior.” In Artistic Country-Seats (1886–87; reprinted by Dover Publications as American Country Houses of the Gilded Age, 24301-X), George Sheldon called it “the pioneer of a new suburban architecture.” In the judgment of twentieth-century architectural historian Vincent Scully, the house revealed McKim, Mead and White “at their original best.”

The house was also a confident statement of American wealth in 1880–81, of summer wealth casually spread with ordinary materials over ample space in a socially acceptable and exclusive location. Sure of themselves, the designers and owners dispensed with traditional architectural means of expressing social status, such as formal composition, thick walls, fine materials, proven styles. Yet, without their confidence and skill, this house could have been interpreted differently, as fragile, vulnerable, tentative, insufficiently imposing, poorly controlled. New owners in 1946 were evidently not comfortable with the risks that had been taken. They transformed the Newcomb house into a one-and-a-half-story structure balanced at either end by related projecting gables held together by a long, quiet roof broken only by three symmetrically placed dormers. The brown shingles were replaced by harder and more serious materials.

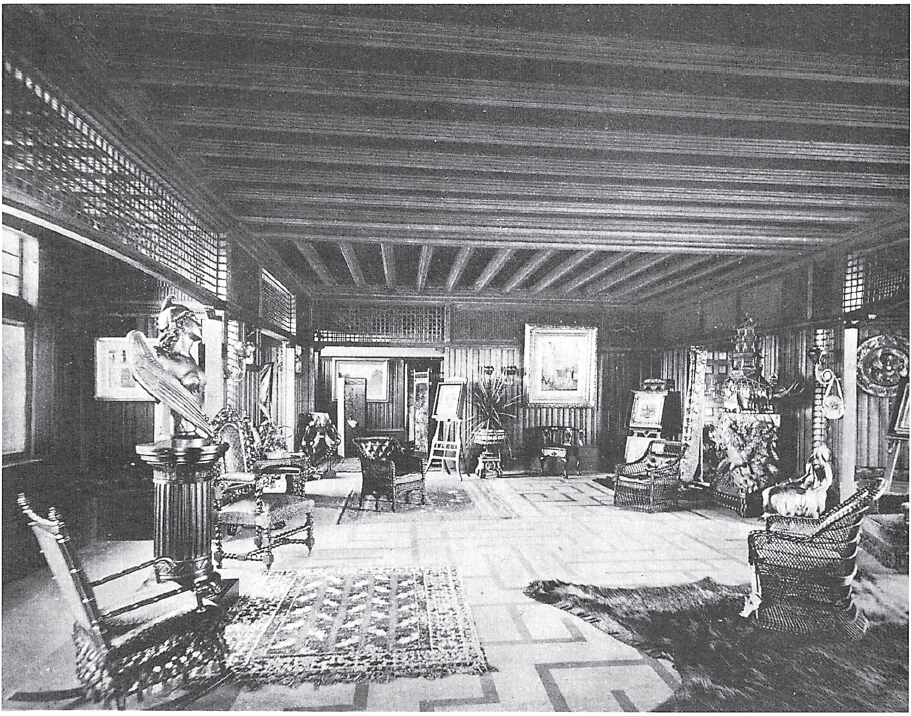

84. Hall, H. Victor Newcomb house, 1265 Ocean Avenue, Elberon, New Jersey; McKim, Mead and White, architects, 1880–81; standing but altered. This photograph, looking north, catches the spaciousness and easy combination of odd items in this living hall, the hub of the house. The principal entrance on the land side led into the vestibule, seen immediately beyond the bay on the left. Directly ahead was the opening into the stair hall that connected with the back hall and the servants’ work area. In the right corner was a reception room overlooking the Atlantic Ocean.

If formality reigned in the Newcombs’ New York town house, informality marked their summer residence. Contemporaries remarked on the “freedom and roominess” of this large space, approximately 50′ × 25′, and twentieth-century observers have complained about the Newcombs’ inclination to clutter it with varied and often uncomplementary furniture and art. It was a superb spatial exercise of the 1880s carried out with a shrewd mixture of craft and daring. Though the space is the provocative agent here, it is difficult to define. Granted, the objects add a peculiar note, but many of them, particularly the wicker chairs, are not heavy, and their thrown-together look fits with the apparent informality of the planning. This space is elusive more because of projections and cavities, its play of light and dark and the constant suggestions of movement of space and vibrations of surface. Suspended from the ceiling, White’s simple but elegant wooden screens further frustrate our attempts to rationalize the space. While they define a geometric area within the hall, the light and space seen through them raise questions about where this space begins and ends. Furthermore, the movement implied in the ceiling beams and the light entering at the bays and other openings encourage us to look to the hall’s edges.

85. Hall, H. Victor Newcomb house. A wide opening on the south side of the hall to the right of the fireplace led to a much more formal sitting room in white and gold, with walls of leather. In the hall the designers contrasted colors, materials and densities. The floor, of brick and marble, was light, the walls and ceiling, of stained American oak, were dark and the screens, unlike the hardness below or the strength above, were delicate. In the Shingle Style (1955), Scully claimed these screens were derived from the Japanese ramma or transom grille. Clay Lancaster, in The Japanese Influence in America, noted this and other Japanese influences in the Newcomb house: “Tangibly Japanese are the ramma in the upper part of the openings into the recesses or adjoining rooms, the beams arranged in groups at right angles in various areas of the ceiling, and a key pattern on the floor carried out in brick and marble instead of Japanese mats.”

86. Entrance hall, David L. Einstein house, 39 West 57th Street, New York, New York; architect unknown, 1882–83; demolished 1912. This ostentatious entranceway served an expensive mansion on West 57th Street, which had become in the early 1880s a most prestigious residential street. Built for a prominent manufacturer, the residence was a massive brick-and-stone turreted Queen Anne structure that was stretched vertically and constricted horizontally to conform to a narrow New York City lot. The narrowness of the lot required a plan substantially different from what would have been built elsewhere. This long central corridor, sufficiently lavish to convey immediately the wealth of the owners, leads to the dining room at the rear of the house and to the main stairway that provides access to the second-floor parlors. The Einstein house was somewhat informal in its asymmetrical plan, lively exterior and the romantic combination of Classical and Gothic themes that marked the major interior spaces. But the ponderous woodwork and conspicuous effects throughout the interior, lavish even by the standards of this period, suggest a conscious effort to reveal wealth and clarify artistic sophistication.

David Lewis Einstein (May 20, 1839–May 7, 1909) was born in Cincinnati. Involved in textile manufacturing, he became president of the Raritan Woolen Mills and head of the Somerset Manufacturing Company, also in Raritan, New Jersey. He married Caroline Fatman in 1870. Their marriage produced three children: Florence, Amy and Lewis, all of whom were raised in this house. Einstein occupied the house until his death; his wife continued to live there until her death in 1912. Little written information survives on Einstein. Since he was Jewish, it is not surprising that his name is absent from the social registers of the era and from contemporary editions of Who’s Who in New York. Evidently he was a self-made man who acquired his fortune, estimated at more than $2 million at his death, through a successful business career. The Einsteins traveled to Europe to purchase a number of items suiting their conservative tastes for their new house.

Entering the interior through a pair of stained-glass doors, one was confronted with the view shown here. The woodwork of the entrance hall was striking in its solidity, massiveness and intricacy. The woodwork covering the ceiling and lower half of the walls is all quarter oak which was darkened by the application of ammonia to give the room an aged character. The process of treating wood to change its color was a common practice of the era; some interior designers applied lime to oak to give it a lighter, whitish color. In this case, the darkening was probably an attempt to make the interior more respectable by creating the illusion of age and stability. Complementing the paneled surfaces were immense leather panels, made to order in France, of subdued red embossed with designs.

Each of the major rooms of the house was designed in its own style. As was common in Queen Anne residences, different woods and other decorative materials were used to create a different effect in each space. Here this approach is carried a step further, as each room represents a different style and historic period. The hall was patterned after the Early English Renaissance, the library was in the style of Louis XIII, the dining room was Henry IV and the sitting room was Anglo-Japanese. At the near right is the entrance to the small Chinese reception room, ornamented in dark blue plush fabric accented by red and gold. Located at the end of the hall was the grand stairway, the focal point of this space, which is illustrated effectively in number 88. The floor shown in this illustration is made of intricate pieces of encaustic tile overlaid with a Persian rug in a Tree of Life design. On the right the oak bench is enlivened by a pair of oak griffins serving as armrests.

87. Living hall, David L. Einstein house. Though treated as a living hall at the end of the main hall, this sitting room was too small to accommodate many people. For this purpose the Einsteins used their Louis XVI parlor located at the front of the house and entered from the left side of the hall. The idea of the living hall was based on the large halls of medieval castles which functioned as the principal congregating space. To heighten the room’s medieval flavor, the owners hung antique shields and swords on the wall and displayed old drinking mugs on the mantel.

The central feature of this living hall was a substantial fireplace, which Sheldon claimed had “one of the thickest and solidest mantelpieces in New York City.” Like most of the major fireplaces in this house, heavily carved woodwork, extending from floor to ceiling, articulated the opening. In this case, the woodwork was particularly robust, highlighted by clustered columns and thick, leafy capitals. The brilliantly polished metal casing that backs the fire opening was so ornate that it is unlikely wood was ever burned here. The absence of pokers and bellows confirm this conclusion. Thus, this fireplace probably functioned ceremonially in a time when central heating was well established. Nevertheless, these owners could afford unused chimneys and flues, and this fireplace, though reduced to a decorative effect, was undoubtedly functional.

Before the fireplace, on the Oriental rug, is teakwood furniture carved in an intricate, weblike fashion. In the foreground the settee, two chairs connected by a common seat, was a shape common in the mid-to late nineteenth century. The walls are finished in embossed leather similar to that of the hallway, and the woodwork repeats the designs a visitor would have seen immediately upon entering the house. Even the paneling of the ceiling is identical to that in the hallway. Suspended from the center of the ceiling is a metal gas lighting fixture with filigree shields.

88. Hall and staircase, David L. Einstein house. This staircase, the final and most spectacular act of the main hall, was a formidable link between the more public spaces of this floor and the more private ones above. Within the jurisdiction of this heavily ornamented enclosure were four separate flights of steps that terminated at the second floor. Walking through and up this massive structure became a ceremonial procession offering unusual vantage points from which to examine the space and decoration. The screen was created by three identical arches; above each were stained-glass panels in an abstract floral pattern. Stained glass was used extensively on this floor, creating, with the darkened oak woodwork and deeply colored leather walls, a dark interior. Striking gas fixtures surmounted each newel post of the stairway, which extended into the hall. In a complicated, if not absurd, lighting system, carved oaken griffins held in their mouths chains supporting a nest of four serpents from whose mouths extended gas burners. When illuminated, the flames looked like flickering tongues. The clustered columns that form the newel posts are medieval in inspiration while the three arched openings above are Renaissance-inspired. The stair rails were heavily carved panels with a free-flowing latticelike pattern.

Though this screen-and-stairway was an impressive achievement, its environment may have been too dark. Furthermore, behind the photographer was a stained-glass bay window illuminated from behind by gas jets, an addition that would have only contributed to the serious mien of this part of the house. Sensing this problem, the Einsteins may have added the brightly colored banner under one of the arches and the scarf on the railing under another to relieve the somberness. The main stairway extended from the first floor to the third floor but did not include the basement or attic. A rear stairway, used by the servants, rose around an elevator shaft, providing access to these floors.

89. Dining room, David L. Einstein house. The dining room was located in a one-story wing at the rear of the house that had a play area on top of it. In this roof garden, surrounded by a high iron railing, the children of the family played, the family sunbathed in warm weather or sought relief on hot summer evenings. This reference to a children’s play space reminds us that the lives of children seldom affected interior planning of these upper-class mansions and almost never the interior decoration.

Because there were no floors above the dining room to interfere, the mahogany beams of the ceiling sloped upward from the sides to the center, creating a sense of height. Despite the dark paneling and heavy floral wall covering, this room was lighter in feeling than the ponderous hall. The woodwork was detailed in a crisp, rectangular manner. Here too, the fireplace was surrounded by floor-to-ceiling woodwork, crowned by a sizable pediment resting on two clusters of peculiar columns. The gasolier, containing metal and stained-glass globes that glowed like jewels at night, was the most elaborate lighting fixture in the house. Not visible in this photograph, a large stained-glass window comprised most of the rear wall.

The Einsteins obtained many of their decorative objects when traveling in Europe. However, most were not antiques, but contemporary copies of museum pieces. Sheldon stated that they owned an excellent copy of a silver goblet for which Baron Rothschild reportedly had paid the astounding sum of $250,000. Their acquisition of copies of European works, as opposed to originals by American artists, reflected the conservative fashion of the time. Many wealthy Americans lacked confidence in American art because most Europeans lacked confidence in it. Dependence on European arbiters of artistic quality may also expose a lack of faith in one’s own judgment. The absence of a separate art gallery in this house suggests that Einstein was not a serious collector of paintings, at least by the standards set by the Stewarts (no. 7), the Smiths (no. 51), the Stuarts (no. 99) or the Vanderbilts (no. 119). Nor was the house well designed to display the objets d’art the couple had collected. Competing with architectural detail for attention, the individual qualities of these pieces were lost in the resulting visual confusion. Paradoxically, then, the greater the number of bric-a-brac attesting to the taste and means of their owners, the more difficulty the admirer had in appreciating the achievement.

90. Library, David L. Einstein house. In this Louis XIII library the usual wainscoting has been replaced by five-and-a-half-foot-high shelves. Although the bindings of the books behind the glass doors may indicate that Einstein purchased sets for display, the fact that this library contained shelves running 50′ suggests that he may have been a serious reader. The room was so tall (16′) that three registers were required to organize the wall surface, and the overmantel looks as if it has been stretched to fill the void. Mr. Einstein’s library—libraries in these days were male preserves—contains comfortable but suitably direct furniture covered with dark leather and velour.

91. Boudoir, David L. Einstein house. Sheldon’s comment on this small sitting room deserves to be quoted because it reveals his positive criticism, writing style and attitude toward European pieces:

We pass now to the second floor, and into the front sitting-room. Its style is Anglo-Japanese. The ceiling is of canvas, hand-painted in greenish blues alternating with tans and reds. The inside panels of the doors recount the story of Orpheus in delicate line-work of gold upon a ground of neutral blue. We see an immense ebony mantel, with cabinets containing bric-à-brac of varied and fine interest—an ivory snuffbox of Louis XIV’s, a miniature Italian guitar enriched with marquetry, old Nuremburg samplers embroidered with exquisite grace, an old Geneva watch, a French harp-clock—an ebony writing-case, fitted up to be a thing of use as well as of beauty, a corner cabinet laden with specimens of Dresden, Royal Worcester, and enamels, one of the Dresden pieces being curious for its successfully illusive treatment of a woman’s gauze veil. Again the visitor is struck with the generous argosies of foreign travel; the host has ransacked the ends of the earth for objets d’art.

92. Reception room, Henry G. Marquand house, 140 Rhode Island Avenue, Newport, Rhode Island; Richard Morris Hunt, architect, 1872–73; destroyed by fire 1973. Marquand (April 11, 1819–February 26, 1902) gave 33 paintings to the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 1889—the first significant collection of old masters the museum received. Marquand deserved much credit for encouraging collectors in the United States to purchase paintings by Renaissance artists when, in 1886, he persuaded the Treasury Department to classify paintings created before 1700 as “antiques” and to exempt them from duty. Active in real estate, banking and railroads, he devoted increasing attention to art during the 1880s and in 1889 succeeded the Metropolitan Museum’s J. T. Johnston, becoming its second president.

The Marquands (he married Elizabeth Love Allen on May 20, 1851) chose Hunt to design this summer house at Newport and their new city residence at 8 East 68th Street in New York City (1881–84). The Marquands displayed so many paintings and objects here at “Linden Gate” that their neighbors dubbed it “Bric-a-brac Hall.” Although he had a reputation for being unable to say no to a persistent bric-a-brac vendor, the army of authorities that gathered for the week-long Marquand sale in January 1903 agreed “he knew what he was buying when he bought.”

This was an unusually formal reception room for a summer house by the shore. Its focal points were the fireplace and overmantel in a wood surround of chestnut that was simple below but not above, where the first register consisted of three panels of tiny figures carved by the Italian sculptor Luigi Frullini (1839–1897). In the center of the next level was Near Lily Pond, Ocean Drive, a Newport scene painted expressly for this spot by R. Swain Gifford (1840–1905). Floral designs decorated the five remaining panels of the overmantel. John La Farge had also worked in the reception room, painting on the blue background of the ceiling Oriental-inspired designs, over which a fretwork of mahogany had been laid. This fretwork was then edged by a border of intricately carved mahogany. Below this border was the cornice, hand-painted against a field of gold, and the wall of eighteenth-century tapestry.

93. Dining room, Henry G. Marquand house. The Marquands found places in the dining room for dozens of their objets dart, particularly their fine pieces of large and petite Chinese ceramics. The overmantel was constructed for display purposes; the Hispano-Moresque chargers at the top look like inlaid discs in a wooden frame. The sideboard held so much that there was little room left over for food and drink. By concentrating on their possessions, the Marquands seem to have deemphasized the function this room served. In competition with the projecting fireplace and sideboard, the table was left with inadequate space. Stretching to the coved frieze, the overmantel may also have been too heavy. On the other hand, we are looking at the windowless corner of the room, in which the woodwork may look more dominant than on the opposite sides. There, light entered through windows with stained-glass depictions of Spenser and Milton.

94. Dining room, Henry Belden house, Fifth Avenue, New York, New York; architect unknown, date unknown. Published information about Henry Belden (d. 1902) is scant, and the specific address of this house is unknown. Evidence suggests that he was the son of the Reverend Henry Belden, a fairly prominent abolitionist and the brother of William, a New York broker. He may have been a partner of William in Belden and Company of 80 Broadway, brokers for rapacious investor Jay Gould. Mentally unstable in his later years, Belden died in a sanatorium.

According to Sheldon:

The dining-room is finished in oak, with a mantel-piece of colored marble. Two immense Chinese porcelain vases stand on either side of the fire-opening, above which the design shows niches for other porcelains and for bronzes; but the shelf is not littered with ornaments. This negative feature is in harmony with the general aspect of the surroundings. There is, perhaps, not a beautiful dining-room in the city whose plan of decoration is at once so simple, without baldness, and so solid. The most striking effect in Mr. Belden’s dining-room is the immense screen of spindle and perforated work.

95, 96. Library and parlor, Sarah Ives Hurtt house, Yonkers, New York; architect unknown, date unknown. Sheldon wrote that the Hurtt house overlooked the Hudson River at Yonkers, directly opposite the Palisades. However, its precise location remains a mystery. It was evidently owned by Mrs. F. W. Hurtt, who was first listed in the Yonkers Directory of 1885 as living at 117 Glenwood Avenue. She died in New York City on July 31, 1907. Her husband, Francis W. Hurtt, possibly deceased in 1883–84, had owned the company that manufactured and distributed Pond’s Extract, an internationally sold panacea for “Piles, Neuralgia, Catarrh, Rheumatism, Diphtheria, Inflamed Eyes, Sore Throat, Toothache, Old Sores, Wounds, Bruises, Scalds, Burns, and all Pain.”

Though it was neither expensive nor conventional, Sheldon thought that this house in “a strictly Moresque style” expressed “an artistic atmosphere.” His choice of words and his emphasis are revealing:

Every article of furniture, except the frames of the chairs, was selected and bought by Mrs. Hurtt herself in Morocco. The hangings are Moorish embroideries on a ground of yellow silk, or a fabric closely resembling silk, the art of manufacturing which is lost. Along the center and extending the whole length of the black-satin cover of the lounge is a Moorish woman’s wedding-sash …. The walls offer a choice assortment of Alhambra decorations, and nearly all the designing is in gold on a solid ground. Between the library and the drawing-room rises a triple arch of true Alhambra pattern, colored in red, gold, blue, and black….

It was said that in such a room no book-cases could be put with any pretext of propriety; but, as books are very useful in a library, the hostess solved the difficulty by getting her carpenter to fit into the walls a series of low shelves ….

In order that the Moorish feeling of the library might not intrude upon the parlor (whose scheme of decoration is distinctly different), the effect of the triple arch was neutralized, so far as the latter room is concerned, by hangings that conceal the two smaller openings. Here the general tone of the furniture and embroideries is a peacock-blue, the furniture being covered with plush of that hue, except the smaller chairs, which show the delicate tint known as robin’s egg blue. The walls are frescoed in yellow and in pale blue, and the frieze of solid gold-leaf looks as if several peacock-feathers had been tossed up and stuck there…. The ceiling is in gold and silver of Japanese design. All the doors are sliding, and, if we push aside the farthest one, we enter the English dining-room ….

Based on this interior and Sheldon’s endorsement of it, we can make the following observations. Freedom of movement was not a major consideration. Mrs. Hurtt had a mind of her own. The terms library and parlor could be interpreted freely. Each side of the dividing archway could contribute to separate and different artistic goals. Eclecticism unified the two spaces.

97. Smoking room, Frank Furness house, 711 Locust Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Frank Furness, architect, after 1873; demolished. The only interior from a professional architect’s house included in Artistic Houses, this den or smoking room was added to the rear of his row house by Furness (November 20, 1839–June 27, 1912). He had spent several summers in the Rockies and had collected the weavings and skins draped on the chairs, sofa and rafter, the stuffed game and ram’s head and local souvenirs, such as the snowshoe. Evidently, he wanted a suitable place in which to put these trophies and reminders. Furness constructed his retreat out of unrefined materials, decorating it in a manner that suggests a Colorado trapper’s cabin. His fireplace was made of irregular pieces of hard rock and capped by a stone shelf that looked as if it had been found instead of prepared.

He chose cedar for the roof and walls and unbarked cedar saplings for the dado. The “rustic” table and stool, also of cedar, were supported by poles trimmed by hand. On the other hand, there was evidence suggesting this was the outpost of a very cultured trapper. Over the mantel were framed prints and caricatures, and on the right wall unframed Western prints and a row of pewter jugs. How refreshing to see a room that has not been meticulously tidied before the photograph was taken!

98. Picture gallery, Joseph G. Chapman house, 1714 Lucas Place, St. Louis, Missouri; Henry G. Isaacs, architect, 1868–69; demolished before 1906. The character of developing cities in nineteenth-century America was often shaped by individuals who were initially successful in business and subsequently used their influence to strengthen local cultural institutions; Chapman did this in St. Louis. He was born in Norwich, New York, on April 27, 1839 and died in St. Louis, October 9, 1897. Following his graduation from Brown University in 1860, he settled in St. Louis, where his father was senior partner of Chapman and Thorp, a prosperous lumber firm with offices in Missouri and Wisconsin. When his father died in 1873, he became vice president and regional head of the newly formed Eau Claire Lumber Co. On October 21, 1868 he married Emma Bridge, whose father headed the hardware firm of Bridge and Beach and was also president of the first line to Kansas City, the Pacific Railroad.

Shortly after their marriage, the Chapmans moved into this house. Isaacs (1840–1895) had studied with Richard Upjohn in New York before moving to St. Louis in 1864. Lucas Place (now Locust Street), an exclusive street requiring a 25′ setback for houses, was blocked from downtown traffic by Missouri Park. The Chapmans’ only child, Isabel, was born here.

For 15 years Chapman was a trustee of Washington University, then only a block from his home. A generous benefactor of the St. Louis Museum, he became its second president in 1883. It is not known when he became a serious collector; however, he frequently purchased pictures exhibited at the Royal Academy Exhibitions in London in the 1870s and probably added this one-story gallery to his house shortly after 1880.

In several respects it was unlike many of the well-publicized galleries of New York City, such as the Vanderbilt (nos. 119 & 120), Stewart (nos. 7 & 8) and Martin (nos. 149 & 150). It was smaller and more intimate. Only 35′ long and furnished with a center table on a splendid carpet, it looked more like a living space than an exhibition hall. The polished butternut floor and hand-carved mantel reinforced this feeling of domesticity. Chapman avoided the institutional appearance of the oblong box by including an annex, seen through the wide arches on either side of the fireplace. He also displayed bric-a-brac as well as oil paintings in this gallery. A marquetry clock in the center of the mantel was flanked by a pair of August Rex Bock vases and crystal candelabra. The oak sideboard against the far wall held a service of Dresden china reportedly manufactured in the late eighteenth century. But the major difference between this room and the galleries mentioned was that it was not crammed from floor or wainscot to molding with pictures. Instead, they were hung close together at eye level. Because this exhibition space was not equipped with overhead gas or electric lighting, the objects could be seen effectively only during the day. This suggests that the Chapmans were not inclined to make an issue of their collection during evening social occasions, that the purpose of the collection may have been private enjoyment rather than a public statement.

Though this collection was not one of “great excellence” containing “examples of the highest art,” as a partisan local writer tried to argue in March 1882, it was unusual among American collections because it contained works by British artists, not just Continental painters. At the far left is A Fishing Haven in the Zuyder Zee by Edward Cooke (1811–1880). In the two pictures to the right, we see a theme popular in nineteenth-century American collections, the struggle for survival in nature. In the center is A Winter’s Tale, painted by Briton Riviere (1840–1920) about 1880; the collies of a search party have just found an exhausted, lost Highland girl. To the right is an account by Adolf Schreyer of a team of horses chased by wolves, Winter Travel in Russia. According to today’s market, his most valuable painting was Dover by J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851), a portion of which is visible on the easel at the lower right.

99. Picture gallery, Mary Stuart house, 961 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York; William Schickel, architect, 1881–83; demolished 1942. Designed in 1881, this house on the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and East 68th Street was completed in the spring of 1883, several months after Robert L. Stuart (July 21, 1806–December 12, 1882) had died of septicemia. Robert and his brother Alexander had inherited $25,000 each from their Scottish father in 1826 and two years later formed the R. L. and A. Stuart Co., a firm that continued their father’s candy business but also branched into sugar refining. They concentrated on refining exclusively after 1835, becoming the largest sugar processor in New York City. That year Robert married Mary McCrea (1810–1891), daughter of David McCrea, a wealthy New York merchant. In 1862, when the lower part of Fifth Avenue was still fashionable, they built a brownstone residence at the corner of 20th Street. After Stuart retired in 1872, he spent much of his time developing his art collection, adding books to his library and giving assistance and money to cultural, medical and educational institutions. Inheriting between $5 and $6 million at his death, Mrs. Stuart continued to give liberally to charities and institutions.

The New York Times predicted the new house would be “one of the most notable of the avenue.” It fronted Fifth Avenue for 55′ and extended 136′ along East 68th Street, was five stories high and cost an estimated $350,000.

At the end of the main hall was the picture gallery, a room that projected from the rear of the house. Compared to the better-known domestic galleries of New York, it was not large; compared to the lesser-known, it was uncluttered and modestly furnished. The chairs were upholstered in carpet fragments. Gas jets on the central rectangular frame augmented natural illumination above. Because of the gallery’s size and the relatively narrow band on which the pictures were hung, only 66 canvases were displayed here. According to an 1885 catalogue, the remaining 174 paintings in the collection were hung throughout the house, most in the halls of the first three floors.

This collection was unlike others featured in Artistic Houses in two respects. First, Stuart had purchased many works by nineteenth-century American painters. Among the 48 Yankee artists included were Frederick Church, Thomas Cole (1801–1848), J. F. Cropsey (1823–1900), Asher B. Durand (1796–1886), Eastman Johnson (1824–1906), William S. Mount (1807–1868) and A. F. Tait (1819–1905). Granted, this number was less than the 63 European artists represented in the collection, but Stuart was a recognized collector and his endorsement of talent in the United States must have encouraged American painters, who clearly understood that New York millionaires preferred to buy their paintings in Paris. Secondly, the Stuart gallery contained more than fine art. In the ebonized oak cabinets below the picture line were rocks, minerals and archaeological fragments, in addition to prints.

Contemporary critics valued the Stuart collection because of its European paintings. Calling it “one of the finest in the city,” the Times cited as evidence works by “Schreyer, Gérome. Bouguereau, Merle, Alvarez, Madrazo, Breton, Verboeckhoven, and others.” In general, the choice of subjects reflected the subjects that also appealed to other major New York buyers; however, there was a much higher percentage of landscapes because of the higher proportion of American painters. The dominant category was clearly genre, with such canvases as The Mother’s Prayer, The Dispute, The Little Knitter—most of them painted by French and German artists. On the left, the larger paintings are Pilgrims Going to Church by G. H. Boughton (1833–1905) and, below, The Quarrel by Ludwig Knaus (1829–1910), Home Lessons by Ludwig Bruck-Lajos (1846–1910) and Tropical Scenery by Church. In the center of the rear wall are On the Esopus by William Hart (1823–1894) and, below, Grandmother’s Birthday by Wenzel von Broczik (1851–1901). In the right corner is Luncheon in the Garden by Munkacsy, below; above, The Bridal Jewels by Giuseppe Ferrari (1843–1905). The posthumous portrait of Stuart was commissioned by his wife.

100. Drawing room, Mary Stuart house. The photographs from Artistic Houses both reveal and obscure. They are revealing because they record for us the physically rich interiors of the 1880s. Yet they are devoid of human beings—those for whom this artistic effort was intended. Consequently, we may understand the material setting but fail to understand how it was utilized. For example, did the guests at one of Mrs. Stuart’s social evenings really sit on these isolated chairs facing various directions?

This space was large enough to absorb, at least partially, the intense decorative attack launched by William Bigelow for Herter Brothers of New York City. The central rectangle of the ceiling contained a painting on canvas of life-size figures representing art. On the frieze, broken into sections by conspicuous brackets, were cherubs playing amid garlands of flowers. Louis XV damask in light cherry covered the walls and also some of the pieces of furniture. An enormous Axminster carpet lay on the floor. On top of this surfeit of dutifully treated surfaces the decorator added focal points: bronze chandeliers with glass crystals attached, two tall Sèvres vases balanced on onyx pedestals and an African onyx mantel capped by the mirror. There were also four paintings on the walls—Study of Natural History by A. Gisbert (1835–1901), The Nine Muses by P.O. J. Coomans (1816–1889), May Festival in Spain by Luis Alvarez (1836–1901) and The Poet by Luis Jiménez (1845–?).

101. Dining room, Mary Stuart house. Like the living room, this room was quite spacious for a New York house of the period. Despite the size and the $150,000 spent to furnish the interiors of the first floor, the dining room was relatively informal, its mood affected by the unexpected presence of the piano, sofa and even the bay window. The vast Turkish rug over the parquetry of the oak floor, and the portieres of blue-green plush embroidered with garlands of flowers, also added warmth to this space. Though the materials differ, the handling of the wall, frieze and ceiling was similar to that of the drawing room. Carefully crafted brackets supported the ceiling of English oak beams. The panels of the ceiling were finished in papier-mâché, those of the frieze in painted plaster and the walls below in stamped leather. Intended to support gas fixtures, the two African marble pedestals of the fireplace look overly precious in this setting impressive for its serious colors and textured surfaces.

102. Sitting room, Henry S. Hovey house, 238 Western Avenue, Gloucester, Massachusetts; Hardy and Day, architects, 1879–81; standing but altered. The Hoveys had spent their summers in Gloucester since the 1850s. Their first house on this site, Lookout Hill overlooking Gloucester Bay, burned in 1875, but in 1879 a son, Henry S. Hovey (January 30, 1844–November 19, 1900), commissioned a second, Queen Anne in style, which was completed in May 1881. Hovey owned the Pittsfield Cotton Mills in Pittsfield, New Hampshire, wintered in Boston at 100 Beacon Street and summered in Gloucester with his sister Marion.

The view from the padded window seat of this sitting room was superb and must have pleased Hovey, who was the owner of the sloop Fortuna and commodore of the Eastern Yacht Club of Marblehead, Massachusetts. The exterior style and setting probably gave license to the casual mixture of objects in this pleasant space: tall case clock, carved table with spiral legs and stretcher, wicker chair, three-legged side chair, horns above the mantel and Oriental ceramics. Despite the dark ceiling and wall panels of stained quarter oak and the parquetry of the floor, the ample natural light reflected from surfaces and gave this potentially heavy interior a lively appearance.