Fig. 1. Samuel P. Hinckley house, Lawrence, New York.

HENRY VILLARD AND THE “GOLDEN MOMENT” OF AMERICAN WEALTH

In 1883, while George Sheldon was preparing his comments on the “magnificent and celebrated” Henry Villard house on Madison Avenue in New York, Villard himself rapidly reached the peak of his career as a railroad entrepreneur. In Sheldon’s description, the house, whose “size is perhaps unequaled by that of any other similar edifice in the city,” aptly matched Villard’s grand-scale ambitions for the Pacific Northwest, which his completion of the Northern Pacific railroad was now opening to the world. Villard saw the Northwest as America’s last productive frontier, able to bring prosperity to countless new farmers and other residents while pouring its grain out to the hungry of Europe. He in turn would be the great organizer of this bounty. Public acclaim was equal to Villard’s expectations, for his efforts had brought success after several years of intermittent railroad construction and now, in September 1883, resulted in completion of the longest single railroad line in the world.

Villard celebrated appropriately, organizing a four-train expedition to open the road and pound the ceremonial last spike. Using the English and German financial connections that had made completion of the Northern Pacific possible, Villard filled the trains with the English, German and Austrian ministers to the United States, several heads of German banks and members of the British parliament, American cabinet members, “two earls and a couple of lords,” and the ubiquitous former President Grant. The journey west from Chicago was an extended triumph. Financiers recognized Villard as the new peer of Jay Gould, William H. Vanderbilt and Collis Huntington, while crowd after crowd cheered the railroad builder and what he meant for their region. The Daily Pioneer-Press of St. Paul asserted that “but few men in the history of the country have ever been the recipients of such ovations as greet Mr. Villard and will continue to greet him as he moves westward.”

Yet even while driving in the last spike on a September evening in western Montana, Villard knew that construction costs were at least tens of millions of dollars above both earlier estimates and his company’s resources. By the end of the year, Villard found himself forced to resign several company presidencies and pledge his property to prevent complete collapse of his empire. Newspaper opinion now pilloried him as a typical example of the corporate looter, a view ironically corroborated by the Villard family’s move at just that time into their new house, which Sheldon described as having “unusual significance” for both “its magnitude and costliness.” The house became the symbol of Villard’s supposed callous selfishness. He knew the move would only increase public hostility, but he had built the seeming palace, actually intended for six families, when his wealth warranted it and now he had no other city home, nor the funds to rent. Villard was never at ease in the house, as the sparsely furnished rooms in Sheldon’s photographs (nos. 183–189) suggest, and in the spring of 1884 the family moved to a country home and soon left the United States for a two-year stay in Germany. As soon as he could, Villard sold the house to Whitelaw Reid, then editor of the New York Tribune. Although Villard had lived in the house less than six months and owned it for little over three years, he gave his name to the group of “Villard houses” that Sheldon recognized would become a landmark, although at the time his reference to their “chaste simplicity” might well have met with jeers from the public that now condemned Villard’s lavish celebrations.

While few of Sheldon’s 92 owners of the “Artistic Houses” experienced such a dramatic rise and fall as did Villard, particularly just as their houses were being publicized, Villard’s career showed elements common to the lives of many of Sheldon’s subjects. Several did indeed rise in fortune dramatically, only to drop as far. H. Victor Newcomb’s rising to “boy president” of the Louisville and Nashville and plummeting into drug addiction and commitment to a mental institution was the most melodramatic of all, but far from unique in its pattern. For many of these men and for others among the house owners whose material fortunes remained stable, the rapid reversal of public attitude was a common phenomenon. Many entered the 1880s almost universally acclaimed as great builders of both their own often immense fortunes and of the country’s material progress, only to find by the end of the decade that the same activities were now condemned as exploitive and parasitic. George Sheldon presented Artistic Houses to the public at what proved to be a key moment in shifting public opinion, marking years in which general fascination at ostentatious display turned to an increasing disgust. While most men of wealth found themselves still admired for their success by the end of the 1880s, it became increasingly necessary to fend off particular attacks and to justify certain of their activities.

Villard further typified many of Sheldon’s house owners in the particular form of his economic success, the consolidation of several separate, often faltering enterprises into one smoothly organized and stable corporate empire. In Villard’s case, although he failed dramatically for a time, the Northern Pacific survived in the hands of others as a solid, major element of corporate America. Virtually all the other great fortunes Sheldon found manifested in the houses stemmed from this same determination to bring order and stability to fragmented enterprises, whether in meat packing, oil refining, retail trade, insurance or any of several other areas. This process of large-scale organization, just like the personal reputations of the organizers, was commonly subject to a sharp change in public attitudes. While many of the “Artistic Houses” were going up physically, the creation of corporate empires was usually hailed as evidence of a distinctive American combination of efficiency and grandeur. Within a very few years in many cases, these same enterprises had become trusts and were being condemned for their rapacious determination to prevent any new competition.

Villard, like many of Sheldon’s men and women of wealth, searched for the right combination of activities and characteristics, both to satisfy his own sense of how a man of wealth ought to behave and to respond to public attitudes. How ought a person of wealth to live and what did such a person owe to society? These were questions much on the mind of many Americans as Sheldon displayed some of the fruits of wealth in such detail. Direct public service by holding elected or appointed office was characteristic principally of Sheldon’s older house owners, such as Presidential candidate Samuel Tilden, Secretary of State Hamilton Fish or New York Mayor James Harper, all born before 1815. Villard’s own way of fulfilling a sense of obligation was less direct but common to his generation. In Villard’s case it took the form of purchasing the New York Evening Post in 1881, in order to save one of America’s most respected newspapers from possible extinction. Villard kept at a distance from daily management, naming three trustees to conduct the business financially and hiring a trio of editors unexcelled in distinction in American journalism: Carl Schurz, Horace White and E. L. Godkin. Many others among the owners of “Artistic Houses” found similar ways to serve, and perhaps elevate, public taste and opinion. The accumulation of art, which the public might view on occasion, and the organization of museums were the most common expressions of a sense of public responsibility, but in other areas George W. Childs secured a reputation as an unusually philanthropic employer, while Robert Paine worked to organize and expand charity and social service in a municipality. Some of Sheldon’s subjects showed an intriguing beginning of the apparent loss of any sense of public obligation, as many of his younger house owners were already gaining reputations as “sportsmen” and “gentlemen of leisure.” For C. Oliver Iselin, sailing became the central preoccupation of his life, while for Bradley and Cornelia Martin, entertainment was their hallmark.

SOURCES OF WEALTH

Who were the owners of the “Artistic Houses”? George Sheldon himself says little about the people who owned the homes he describes, providing only scattered information about individuals, nothing at all about the owners as a group, and occasionally even using only a last name. Nevertheless, it is possible to discover significant information about the great majority of Sheldon’s house owners. Of the 84 men listed by Sheldon as house owners, only two, Henry Belden and F. W. Hurtt, remain too obscure for us to be sure of anything about their lives. Hurtt, in fact, may not have been living when Artistic Houses was published. Because of this possibility his house has been listed under the name of his wife, Sarah Ives Hurtt. Sheldon also referred to “Mrs. John A. Zerega’s House” (nos. 24–26), but we have listed the residence under her husband’s name because he was living in 1883–84. Five of the eight women owners were well known in their own time, either because of their own work, as in the case of Clara Jessup Moore, a successful writer, or as widows of prominent men, as was true of Julia T. (Mrs. James) Harper and Cornelia M. (Mrs. Alexander T.) Stewart. Yet three women owners are uncertain figures, and we know little or nothing about them.

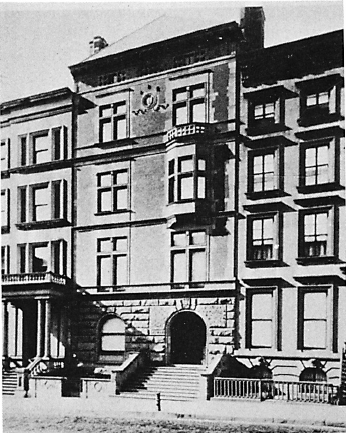

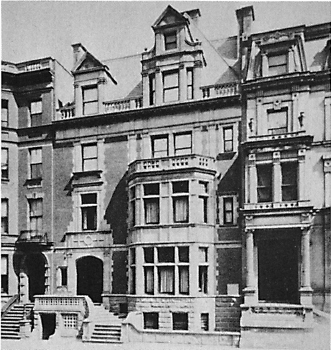

Not surprisingly, Sheldon found most of the people whose homes he wanted to present along the Eastern seaboard. His own career had developed in New York and Americans assumed that the most up-to-date taste moved from East to West. Accordingly, 40 of Sheldon’s 92 owners were studied with respect to homes they owned in New York, while ten more persons lived in “Artistic Houses” in the New York suburban area, stretching from Henry M. Flagler in Mamaroneck, New York, and Samuel P. Hinckley in Lawrence, Long Island, to William I. Russell, Franklin H. Tinker and O. D. Munn in the newer, planned New Jersey suburbs of Short Hills and Llewellyn Park. Three other men commonly lived in New York, but Sheldon preferred to describe the Newport homes of Samuel Colman, Robert Goelet and Henry G. Marquand.

Fig. 1. Samuel P. Hinckley house, Lawrence, New York.

Boston provided Sheldon with his next-largest concentration of homes, with 13 of his houses in Boston itself and four others in outlying towns, owned by men who earned their livings in Boston. Next came Philadelphia, providing ten homes that Sheldon described, including two of publisher George W. Childs’s houses, one in the city and one in Bryn Mawr. After Philadelphia, only Chicago provided a cluster of house owners for Sheldon, giving him four. Although Newport also yielded four houses for Sheldon’s study, only George P. Wetmore considered the town his principal residence.

Sheldon found eight more men and women who owned “Artistic Houses” scattered as far west as St. Louis, where lumber merchant Joseph G. Chapman’s home was known “even in the East” for its “artistic treasures.” The southern boundary to Sheldon’s interest was Washington, D.C., where General Nicholas Longworth Anderson’s new home, designed by H. H. Richardson, was “easily the most interesting private residence in the capital.” In upstate New York Sheldon found three homes to include, those of woolen-mill owner Swits Condé in Oswego, tobacco manufacturer William S. Kimball in Rochesterand the Geneseo home of gentleman farmer James W. Wadsworth. In New England, aside from Boston and Newport, Sheldon described three more homes. The new Bar Harbor home of Mrs. G. B. Bowler was being studied at the same time in a series of Century articles on contemporary architecture. Sheldon also included the home of silk-mill owner Knight D. Cheney in South Manchester, Connecticut, and the Providence, Rhode Island, home of another textile magnate, William Goddard. The inclusion of houses in such varied locations gave Sheldon’s work a semblance of comprehensive coverage, but over four-fifths of his examples were from his three main metropolitan areas.

Sheldon’s house owners were quite varied in occupation, representing most of the major sources of substantial wealth in the late nineteenth century. Yet the newer types of industrial activity were underrepresented. In the 1880s, railroads and iron and steel manufacturing were still the most fruitful newer sources of fortunes, joining the somewhat older textile mills as the principal foundations for industrial wealth. Only the relatively little-known John H. Shoenberger, who had recently retired from business and moved from Pittsburgh to New York, represented the substantial iron and steel industry. Railroads played a larger part in the wealth of Sheldon’s subjects, but a proportionally small one considering their importance in the national economy. William H. Vanderbilt was one of Sheldon’s best-known house owners, a man whose control of the New York Central and other lines had made him a principal public symbol of railroad wealth. Also well known when Sheldon was writing was Henry Villard, as mentioned, a principal figure in the Northern Pacific. Two other men had made their initial fortunes in railroads but were not actively involved when Sheldon described their homes: John Taylor Johnston had been president of the Central Railroad of New Jersey for 30 years, until the depression of the 1870s led to a reorganization of the line; H. Victor Newcomb became president of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad following his father, but resigned the position in 1880, as his interest turned more toward New York banking. Two other men also represented the newer forms of industrial activity. Henry M. Flagler possessed “one of the great fortunes of the United States” as a result of his partnership with John D. Rockefeller in the Standard Oil Company, while Edward H. Williams rested his wealth on his partnership in Philadelphia’s Baldwin Locomotive Works.

The older industrial activity of cloth and clothing manufacture was an important source of wealth in Sheldon’s group, accounting for eight of his home owners. Henry S. Hovey and William Goddard owned cotton mills, Swits Condé and David L. Einstein woolen mills and Knight D. Cheney and William De Forest silk mills. William Clark was well on the way to becoming one of America’s major producers of cotton thread while John T. Martin had made a fortune in clothing production during the Civil War, after which he diversified into banking and real-estate investment. Martin’s pattern was common to many of Sheldon’s subjects, who achieved substantial wealth in one field, but then increased it by activity in two or three others.

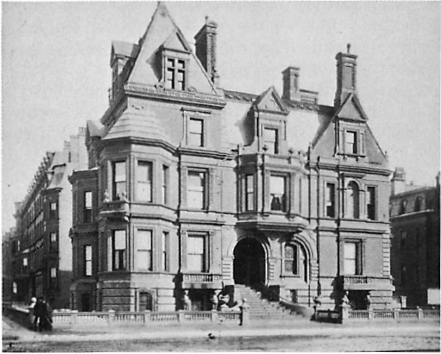

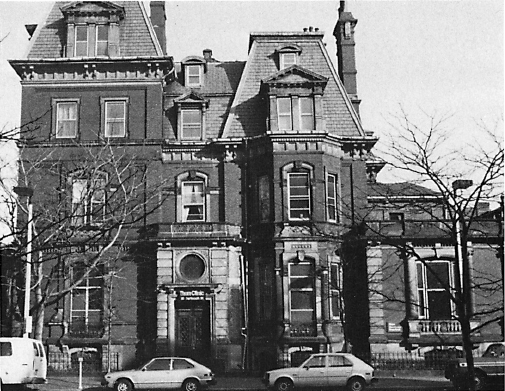

Fig. 2. William Clark house, Newark, New Jersey.

As with cloth and clothing, older types of raw-material processing were the foundation of the wealth of several of Sheldon’s house owners. Like Standard Oil’s Flagler, Herman O. Armour, one of four brothers in the meat-packing business, represented one of the better-known new fortunes of the post-Civil War era. William F. Havemeyer and Robert Stuart in sugar refining, Henry C. Gibson the Philadelphia distiller and Jacob Ruppert the New York brewer, Joseph G. Chapman in lumber milling and William S. Kimball the tobacco processor, rounded out this source of wealth among Sheldon’s people.

Trade was another important activity for Sheldon’s subjects. The most common figure was the dry-goods merchant, often a man who built up a substantial general hard-goods trade. Both A. T. Stewart and Marshall Field were preeminent in the developing department store, while Chicago’s Henry J. Willing had accumulated his fortune with Field before retiring to travel. Ralph H. White built up a major retail dry-goods firm in Boston and Charles Stewart Smith secured his wealth from the wholesale dry-goods business in New York. Also prominent in New York merchandising were George Kemp in drugs and toiletries and John Wolfe, who inherited his hardware business from his father. The sale of coffee, tea and groceries provided the origin of Chicagoan John W. Doane’s millions, while the general import-export trade with China and the Philippines occupied John Charles Phillips in Boston. The China trade had also been the principal source of John L. Gardner’s inherited wealth, but Gardner himself put the money into railroads, mining and other investments. Also in Boston, Gilbert R. Payson and Joseph H. White were partners in a firm marketing textiles for major New England mills.

Banking was the principal occupation of almost a dozen of Sheldon’s owners and a major activity that many others took up after they had accumulated a fortune in some other field. Among Sheldon’s bankers, J. Pierpont Morgan had already established a solid reputation in railroad financing. Morgan’s conspicuous investment activity, accompanied by growing public attention, was almost the opposite of the quiet “bankers’ bank” business of George F. Baker, who with Morgan would soon become one of the country’s most powerful financiers. Sheldon found bankers prominent among his house owners in all his major cities, with the Hunnewells and Asa P. Potter representing Boston and Samuel M. Nickerson prominent in Chicago. In Philadelphia, Clarence H. Clark of the First National Bank was reputed to be one of the city’s richest citizens. Rounding out Sheldon’s group of bankers were several New Yorkers, including Joseph S. Decker, Frederic W. Stevens, Frederick F. Thompson and Richard T. Wilson, whose banking was much less well known than the socially advantageous marriages of his children.

The related fields of brokerage and insurance accounted for several other house owners, including James W. Alexander, first vice president of the Equitable Life Assurance Society, one of the largest firms in the field. Edward Eddy Chase, William G. Dominick, Rudolph Ellis and E. Rollins Morse all participated in stockbrokerage firms, while William I. Russell handled investments in metals.

Fig. 3. E. Rollins Morse house, Boston, Massachusetts.

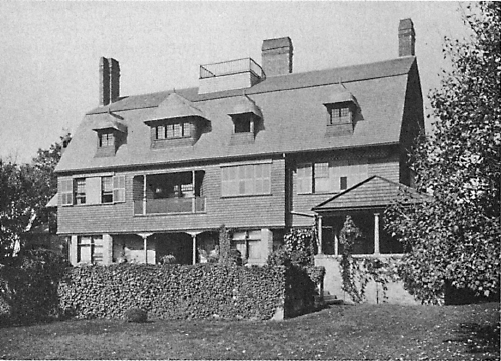

Along with banking, real-estate investment was an activity that provided the central wealth of several house owners and a secondary activity for numerous others. Robert Goelet was heir, with his brother, to one of New York’s major real-estate fortunes, begun in the early nineteenth century. Goelet needed to involve himself little in active management of the investments, as their value steadily increased with the growth of New York. Similarly, Nicholas Longworth Anderson in Washington lived a life of leisure on income from Cincinnati real estate developed by his grandfather Nicholas Longworth, the “first millionaire of the West.” Samuel P. Hinckley took a more active role as a real-estate dealer on Long Island, while James W. Wadsworth managed the landholdings his father had put together in upstate New York. The income of these four was most clearly tied to land, as was the inherited wealth of Mariana Arnot Ogden, widow of one of Chicago’s earliest major landowners, William Ogden.

Real estate and banking also provided significant second careers for many of Sheldon’s men of wealth, so that to some extent categories break down. John T. Martin, for instance, made enough money in a St. Louis clothing firm to retire before he was 40, in 1855. He then moved East and soon made a substantial fortune by means of uniform contracts during the Civil War. “Retiring” again, he concentrated on developing his increasingly significant collection of sculpture and paintings, but also served as a director of a half-dozen banks and trust companies and managed his large tracts of Brooklyn waterfront land. Many others, including William Goddard, George Kemp and Henry G. Marquand, followed similar paths, so that when Sheldon described their houses in the mid-1880s, they were as much or more involved in banking and real estate as in their original occupations.

Fig. 4. John T. Martin house, Brooklyn, New York.

One other business, publishing, was a significant occupation of Sheldon’s house owners. George W. Childs, owner of the Philadelphia Public Ledger, was one of the best-known newspaper publishers of his generation. The Ledger’s “exceptionally high tone,” which put it on “the right side of every question,” had made it both eminently respectable and financially rewarding. This success and Childs’s active philanthropy made him one of Philadelphia’s most eminent citizens, a fitting host for President Grant and the Emperor of Brazil when they arrived in Philadelphia to open the Centennial Exhibition in 1876. One of Childs’s competitors, William M. Singerly, who published the Philadelphia Record, was responsible for the only “artistic office” in Sheldon’s collection. Sheldon’s only other newspaper publisher was Oswald Ottendorfer, owner of one of the country’s most important foreign-language papers, the New York Staats-Zeitung. Ottendorfer had married the woman principally responsible for the paper’s early success, Anna Behr Uhl, who died as pictures of the couple’s “Beautiful pavilion on … the North River” were being published. Sheldon included two magazine publishers, the young Franklin H. Tinker, whose firm published several trade journals, and O. D. Munn, whose Scientific American had been an important periodical since the 1840s. Another of Sheldon’s house owners, Julia Thorne Harper, owed her inherited wealth principally to publishing, but she took no active role in Harper and Brothers, the firm that her husband James had helped to found.

Among the professions, law provided Sheldon with several house owners. Both Hamilton Fish and Samuel J. Tilden had legal practice at the center of their careers, but both had expanded their incomes with real estate and corporate investments and both had devoted much of their energy to political life. Fish capped his career with service as Secretary of State throughout the Grant administration, while Tilden went from the governorship of New York to an unsuccessful campaign as the Democratic nominee for President in 1876. When Sheldon described their houses, both were elder statesmen of their respective parties, each living “the private life of a gentleman of ample means and cultivated tastes.” Owing his reputation more clearly to his legal practice was Edward N. Dickerson, one of the country’s ablest patent lawyers, whose cases had included tests of Colt firearms and Goodyear rubber patents. In Boston, Robert Treat Paine, Jr., was a lawyer whose practice enabled him to find the profitable railroad and mining investments which, in turn, allowed him to retire to public service and philanthropy in 1870, at the age of 35. Several more of Sheldon’s subjects trained in the law and were members of the bar, including J. Coleman Drayton, Judge Henry Hilton and Bradley Martin, but legal practice was not a significant source of their income.

Fig. 5. Julia T. Harper house, New York, New York.

Medicine contributed two of Sheldon’s more accomplished house owners and one of his obscure ones. Dr. William A. Hammond had been Surgeon-General of the United States Army during part of the Civil War, but his “masterful personality” clashed with the “autocratic spirit” of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and he was dismissed in 1864. While spending 15 years winning reversal of his court-martial verdict, Hammond also became an authority on nervous diseases and “one of the pioneer neurologists of the United States.” Dr. William T. Lusk, by the mid-1870s “the fashionable obstetrician of the day” in New York, marked the opening of the 1880s with publication of his Art and Science of Midwifery, the most learned textbook on the subject at the time. Dr. Henry C. Haven, the third of Sheldon’s physicians, practiced in Boston, where he specialized in the diseases of infants and helped found several medical institutions for children.

Three of Sheldon’s owners made their livings in the arts, helping to create and decorate just the kind of homes Sheldon wanted to present as models for up-to-date taste. In the mid-1880s, Philadelphia’s Frank Furness was just reaching the apex of his career as an architect. Having already designed several important public buildings in his hometown, he was now being called on by the city’s banking and railroad magnates for both office buildings and suburban homes. Samuel Colman, a Newport painter who had begun to receive recognition during the Civil War years, also created during the 1880s designs for fabrics and wallpapers and experimented with interior wood stains. Similar experimentalism characterized the third of the professionals in the arts, Louis C. Tiffany, who had studied painting under Colman before turning toward more varied decorative arts, especially the many uses of stained glass. Another of Sheldon’s owners, Clara Jessup Moore, was a prolific author, but did not think of herself as a professional. While her husband lived, Moore published social advice, poetry and short prose under pseudonyms for about 20 years. By the late 1870s, living on the fortune from her late husband’s paper-manufacturing business and donating to charity the proceeds of her writing, Moore published more frequently under her own name and became a popular writer of novels and children’s stories.

Two of society’s traditionally honorable professions, the clergy and the military, were also represented among Sheldon’s people. Phillips Brooks, in the 1880s still the minister of Boston’s Trinity Episcopal Church, was among the country’s most widely known clergymen. He had turned down academic offers from Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania in order to remain in the church, a commitment rewarded a few years later when he was chosen Bishop of Massachusetts. Sheldon’s military figures included Nicholas L. Anderson, Charles A. Whittier and Ulysses S. Grant. Grant, who had commanded the victorious Northern forces in the Civil War and then served two terms as President of the United States, was in these years facing the last of many low points in his life. His investment firm failed in 1884 and in the same year he discovered the cancer that soon killed him, but not before Grant’s characteristic determination had enabled him to complete his Memoirs.

Fig. 6. Trinity Church rectory, Boston, Massachusetts.

While their professions provided the shape and focus of the lives of most of Sheldon’s house owners, a sizable group found earning an income of no particular significance. Inherited wealth was not the defining characteristic of these house owners, for others among Sheldon’s subjects had fallen heir to fortunes but had devoted their efforts to active management of inherited businesses. The single wealthiest owner in Sheldon’s array, William H. Vanderbilt, was also well known for his constant attention to his railroad empire. Others, such as Samuel J. Tilden and Hamilton Fish, gave a large part of their lives to public service, but only after strenuous effort in accumulating the fortunes that made such service possible. Unlike these men were the house owners who spent all their lives as men of leisure or the few who did engage in cultural or political activity made possible by wealth they had done little to develop.

Assignment of some men to such a category represents a judgment not strictly factual and objective. Robert Goelet, for instance, was seen as “uncommonly sagacious” in augmenting the immense New York real-estate fortune left to him and his brother by his father and uncle, but such activity seems never to have provided the focus to his life, which he devoted to music, sport, club life and travel. The Metropolitan Opera and his magnificent steam yacht represented his paramount concerns. A more clear-cut example of the man of leisure was Bradley Martin, a man who “began at college the social career in which he subsequently attained such a conspicuous place as a leader of society both in America and Europe.” When Martin married Cornelia Sherman in 1869, he married the fortune that launched them both on an increasingly lavish series of balls and enabled them to spend the last portion of their life in Britain, after public reaction to their depression-era ball of 1897 made life in America too unpleasant. Skill at leisure activity was seen as most noteworthy in such others as New York banker’s son C. Oliver Iselin, “whose love of sports and his prowess in coaching, polo, hunting, quail and pigeon shooting, made him a notable and colorful figure.” Iselin, from one of the country’s wealthiest families at the time, was especially well known as a yachtsman and defended the America’s Cup in three famous races.

If Iselin used wealth to cultivate a firm mastery of recreational skills, other house owners demonstrated a talent for scandal and defeat. When Sheldon was describing his home, J. Coleman Drayton was coasting smoothly through an active social life that rested on the fortune of his wife, Charlotte Astor, whose family combined wealth and social distinction as few others did in the 1880s. By the end of the decade the Draytons were headed toward the separation and subsequent divorce that became the “most conspicuous society scandal of the generation.” Less explosively dramatic but equally precarious in his good fortune was Henry Hilton, early in his career an inconsequential municipal judge in New York. Hilton’s wife was a cousin of the wife of department-store millionaire A. T. Stewart, a connection the Hiltons carefully cultivated. The matter-of-fact Stewart made Hilton his social master of ceremonies and friend, coming to treat him as a son and leaving in Hilton’s hands management of the fortune he left his widow upon his death in 1876. As custodian of Stewart’s millions, Hilton lived lavishly, bought a luxurious house, donated freely to charity, but so mishandled Stewart’s business, especially after Mrs. Stewart’s death in 1886, that he rapidly ran through and dissipated the huge fortune ($20 to $40 million) that observers estimated he began with.

More productive in their use of inherited wealth were John L. Gardner of Boston and George Peabody Wetmore of Newport. Neither had much involvement in the businesses their merchant fathers created and both initially used their wealth for extended and frequent tours of Europe. Gardner, and particularly his wife, the former Isabella Stewart, soon became increasingly committed to sponsorship of the arts in Boston, while Wetmore entered Rhode Island politics in the mid-1880s, starting at the top with election as governor in 1884.

A quieter life, free from both great scandal and notable achievement, characterized Sheldon’s remaining families of leisure. Representative of several was the amalgamation John Hay saw when he ushered at the wedding of William Sprague Hoyt and Janet Chase in 1871: “He is a very nice fellow—and no end of cash. She is a very nice girl—and no end of talent.” Although Hoyt’s cash had its ups and downs depending on the fortunes of his cousins’ cotton firm, and although Mrs. Hoyt’s connections with national and Rhode Island politics (through her father and brother-in-law) sometimes presented problems, the marriage included European and Caribbean travel, a comfortable home the couple designed for themselves on an island near Pelham, New York, and enough jewelry to warrant newspaper coverage of its theft, with time for Janet Chase Hoyt to gain a reputation as a writer and illustrator of children’s books. Apparently similar was the life of Charles A. Whittier and his wife Lillie, who divided their time between homes in Boston, Buzzard’s Bay and New York; traveled frequently to Europe; and married one daughter to a wealthy Iselin and the other to a Russian prince.

Such families devoted themselves chiefly to private pleasures, often centered in the homes Sheldon presented. For some, personal enjoyment and their home became a preoccupation equivalent to a business career for others. Sheldon notes that Egerton Winthrop imported from France every article of furniture in his New York apartment (nos. 53 & 54), including papier-mâché ornamentation. Winthrop had spent much of his early married life in France, where his second son was born, and he became a pioneer in the use of antique French furniture in America. His concern with taste in art led novelist Edith Wharton to find in Winthrop her first real adult friend, the first to provide her with “intellectual companionship.” As Winthrop turned more and more toward devotion to such amenities as the perfection of his dinners, Wharton described him in a way that suits many of Sheldon’s men of leisure: “Never, I believe, have an intelligence so distinguished and a character so admirable been combined with interests for the most part so trivial.” For Winthrop, the rooms themselves that Sheldon portrayed, and the activities he orchestrated in them, became essentially the entire content of his life.

DEFINING AN AMERICAN ELITE

Fortunately for later researchers, the contemporaries of Sheldon’s house owners were becoming increasingly interested in establishing and defining categories of elite status in America. Wealth and social prestige had long fascinated Americans, in part because possession of either could change so rapidly, in part because great wealth and high status paradoxically both affirmed and denied American tenets of social mobility, individual ambition and egalitarian democracy. As a result of this American fascination with wealth and status, there had always been impressionistic identification of the richest or most well-born Americans. In the 1880s, both outside observers of the wealthy and those who saw themselves as inside guardians of “society” began to be more systematic and explicit in their defining of categories, producing extensive lists of families and individuals. The lists, among their other functions, help to define Sheldon’s house owners.

Among the first to attempt a comprehensive identification of men of great wealth was Thomas G. Shearman, who intended his series of articles for The Forum in 1889 and 1891 as an alarm signal calling attention to the growing concentration of wealth in the United States. In an effort to prove that the “wealthiest class in the United States is vastly richer than the wealthiest class in Great Britain,” which Americans were used to thinking of as an aristocratic society, in 1889 Sherman published a list of all those Americans easily identifiable as having at least $20 million in individual wealth. His 67 people and estates were those commonly accepted as the very top level of wealth in America. Although his list was current for the late 1880s, and thus came after the death of some of Sheldon’s house owners, eight of them figured in Shearman’s list in some way. Henry M. Flagler, J. Pierpont Morgan and Marshall Field were counted as individuals; William H. Vanderbilt’s spirit was present through the listing of several of his heirs; and inheritance or other family connections gave Herman O. Armour, Robert Goelet, William F. Havemeyer and Cornelia M. Stewart either a place on, or a link with, Shearman’s list.

Shearman’s efforts, as well as a rising public concern with concentrated wealth, led to an even more careful study by the New York Tribune in 1892. The Tribune’s interest was prompted by arguments that recently raised protective tariffs were responsible for unjust concentrations of wealth. The protariff Tribune hoped to show that most Americans who possessed great wealth gained it in fields that received no advantage from the tariff, but overall it also devoted great time and effort to accumulating the most accurate list of all Americans who were worth $1 million or more. After much correspondence and cross-checking, the Tribune’s researchers discovered and listed 4047 millionaires from all over the country, about .0001 percent of the adult population.

As with Shearman’s list, the Tribune’s came too late to include those of Sheldon’s owners who had died in the 1880s. Thirteen of the owners of “Artistic Houses” had died by the time of the Tribune’s list, yet even so five of them were represented. Three men whose houses Sheldon described (Anderson, Shoenberger and Vanderbilt) had passed on sufficient wealth so that their widows merited inclusion on the list of millionaires, while two (Gibson and Phillips) had their estates listed. Mrs. James Harper, a widow, was not listed, but all of her brothers-in-law were, while the fathers of three other house owners (Hovey, Walter Hunnewell and Tiffany) were included by the Tribune, though the sons were not. The Tribune listed the wives of four men whom Sheldon considered the owners of houses (Drayton, Iselin, Bradley Martin and Wadsworth) as millionaires by inheritance, but not the husbands. Fully 44 more of Sheldon’s subjects, almost half his group, made it onto the Tribune list in their own right. Twenty-two of the house owners who were still alive in 1892 had not accumulated enough wealth to merit inclusion, while in the case of five it is not known if they were still alive or where they were living.

According to the Tribune’s systematic assessment, one major characteristic Sheldon’s house owners had in common was great wealth, for almost two-thirds of his subjects, either personally or by family association, rated inclusion in the category of millionaire, the pinnacle of the pyramid of wealth in America. Even among the 22 men still living in 1892 but not ranked as millionaires or represented by a relative, many had accumulated substantial wealth. James W. Alexander was vice president of the Equitable Life Assurance Society, one of the country’s major insurance companies. Knight D. Cheney was moving up toward the presidency of his family’s silk mills, the largest in the country. Although neither Frederic W. Stevens nor Frederick F. Thompson, had amassed a million dollars, each was director of a half-dozen significant New York banks, insurance companies and other financial institutions. Still others, who lacked a million of their own, constantly rubbed shoulders with the very rich, either as their pastor (the Reverend Phillips Brooks), their decorator (Samuel Colman) or their architect (Frank Furness). Among those dead by 1892, the year of the Tribune’s list, and not represented by heirs, Cornelia M. Stewart had briefly enjoyed one of the country’s great fortunes and several others, such as James L. Claghorn, Edward N. Dickerson and Samuel J. Tilden, had been men of substantial wealth.

Thus, the homes Sheldon presented were owned almost entirely by men and women of unusual wealth. In a few cases, notably those of Marshall Field, Henry M. Flagler, Robert Goelet, J. Pierpont Morgan, Cornelia M. Stewart and William H. Vanderbilt, Sheldon was discussing homes owned by people of legendary wealth, the sort of immense fortune that made the family name a household word throughout America.

In dozens of other cases, Sheldon’s subjects constituted what English observer James Bryce identified as one of “the most remarkable phenomena” of the late nineteenth century, the rapidly growing class of “millionaires of the second order, men with fortunes ranging from $5,000,000 to $15,000,000.” The prosperity of the 1880s was creating a great surge of such wealth, a development that fascinated the general public, alarmed reformers and perplexed Society itself.

With the great rise of new fortunes, various leaders of Society decided it was necessary to define the boundaries of acceptability. Of course, there had always been social definition, but it had been largely informal and simply in the minds of those who belonged. As late as the 1870s, according to such old-family representatives as Edith Wharton and Mrs. John King Van Rensselaer, it had still been possible for “New York Society” to be “a representative, exclusive body of all that was best in the city,” on a basis of mutual recognition and privately agreed-upon invitation lists. Then, according to Wharton, “the first change came in the ‘eighties, with the earliest detachment of big money-makers from the West.” Just as the great increase in “millionaires of the second order” had led journalists to develop their explicit, categorized lists of the wealthy, so too the influx of new families led to a formalization of membership in Society, most clearly exemplified by the Social Register.

The Social Register was another new phenomenon of the 1880s, designed to end confusion as to who truly belonged in Society. American journalists had been attempting to define Society, looking for “Class Distinctions in the United States” or “Caste in American Society,” but they found themselves puzzled. One writer, Kate Gannett Wells, reported that she had been to eight society functions in a week and had not seen one person twice. “Where is society?” she asked. “At each door there were carriages, and each house was well appointed. Some would fold their napkins; others would throw them crumpled on the table. Some would have wine, others water.” She could find no certain key to Society behavior and membership. The Social Register sorted this out, both recording and in a sense creating in print the formal Society that the 1880s called into being. Published by the Social Register Association, the first volume of the Register appeared in 1887 and naturally devoted itself to New York. Listing fewer than 2000 families, the Register included Dutch and English families from the colonial era, families who had made fortunes and gained status in the early nineteenth century and some of the more recent arrivals.

Forty-nine of Sheldon’s house owners were still alive in 1887 and in the New York area. Of them, 28 merited inclusion in the first Social Register, a slightly lower proportion than earned their place on the Tribune’s list of millionaires. Among Sheldon’s members of Society were several whose families had been prominent for several generations, such as the Fishes, the Goelets, the Iselins and the Winthrops. Early-nineteenth-century wealth was represented by such men and women as Julia T. Harper and William F. Havemeyer. Some of Wharton’s “moneymakers from the West” (and others from the South) won a listing as well, among them H. Victor Newcomb, born in Kentucky and at the beginning of the decade the youngest president of a major railroad, the Louisville and Nashville. Another post-Civil War arrival in New York Society was Richard T. Wilson, a Georgia native who settled in New York in the 1860s with money gained marketing Confederate cotton in England. Still others of Sheldon’s owners gained a presence in Society primarily through professional contacts. Two of his physicians, William A. Hammond and William T. Lusk, acquired only moderate wealth but were well known as society doctors.

Doctors Hammond and Lusk, in their Social Register inclusion but absence from the Tribune’s list of millionaires, represented six other New York-area owners of “Artistic Houses.” James W. Alexander and William Sprague Hoyt were others who had inherited or married social connections, but failed to achieve great wealth. Among Sheldon’s New Yorkers, the largest single group consisted of those 19 house owners who were both socially prominent and wealthy. All of the wealthy owners noted above were in the group, as were bankers George F. Baker and J. Pierpont Morgan; such substantial merchants as George Kemp, Henry G. Marquand and John Wolfe; and John T. Johnston, a railroad investor. Edith Wharton might have been pleased to note that there were a dozen house owners with enough wealth for the Tribune who had not been accepted into Society and that such Western millionaires as Herman 0. Armour, Henry M. Flagler and John H. Shoenberger were prominent in the excluded group. They were joined by Sheldon’s one Jewish house owner—David L. Einstein—and several millionaires of German immigrant background, such as Oswald Ottendorfer, Jacob Ruppert and Henry Villard. Eight of Sheldon’s New York-area owners were not distinguished for either wealth or social prestige in the 1880s.

Fig. 7. Jacob Ruppert house, New York, New York.

The Social Register Association followed its New York debut with volumes for Boston and Philadelphia in 1890. The first Philadelphia Social Register was much smaller than New York’s—one-tenth the names for a city about half the size of New York. Of Sheldon’s Philadelphians, only James L. Claghorn had died by 1890. Among the others, George W. Childs, Frank Furness, Henry C. Gibson and Clara Jessup Moore had earned state or national recognition for their achievements or philanthropy and, except for Furness, they owned at least the $1 million that the Tribune looked for, as did three others of Sheldon’s group, but neither wealth nor achievement won them or any other owner inclusion in Philadelphia Society, a group noted in the late nineteenth century for its high degree of exclusiveness.

Fig. 8. Joseph H. White house, Brookline, Massachusetts.

Boston Society, on the other hand, was more inclusive or else Sheldon had selected his Boston owners in a different way, for, of 16 families who owned houses in Boston itself or in nearby towns, 12 merited inclusion in early Social Registers. An additional person, Phillips Brooks, died too early for listing in the extant Registers but surely would have been included. Of Sheldon’s owners, only two Boston merchants, Joseph H. and Ralph H. White, banker Asa P. Potter and Elizabeth E. Spooner failed to be listed. In Boston, then, Sheldon had a group with an unusually high proportion of membership in the social elite. The other house owners lived in cities which produced Social Registers only in the 1890s or never, but there is no question that men like Joseph G. Chapman, trustee and benefactor of Washington University and the St. Louis Museum of Fine Arts; John W. Doane, who presided over one of Chicago’s banquets for Ulysses S. Grant after completion of his world tour in 1879; or William S. Kimball, one of Rochester’s foremost businessmen and philanthropists, were considered among the elite of their communities. Overall, Sheldon assembled a group that enjoyed not only great wealth but high social status.

THE UPPER CLASS ORGANIZES CULTURE, LEISURE, EDUCATION AND MANNERS

The Social Register was simply one way in which the American upper class attempted to define itself and achieve what proved to be an elusive stability and organization. In the 1880s, such an achievement of order still seemed possible and Sheldon’s owners played an active role in most of the activities designed to bring it about. To some extent, the efforts of the 1880s built upon, yet in a way opposed, earlier work by an upper class that thought of itself as more exclusive. This earlier elite included some of Sheldon’s older house owners, among them Hamilton and Julia Kean Fish, pillars second to none in New York’s Knickerbocker aristocracy. The home itself was central to social organization, for Mrs. Fish’s invitations were crucial in defining who belonged and who did not. While she (no. 52) or such a friend as Elizabeth Marquand (nos. 92 & 93) hosted a “limited but exceedingly brilliant gathering of society people” in their homes, Hamilton Fish took his turn presiding over the older cultural institutions, such as the Academy of Music and the New-York Historical Society, that helped define his generation’s elite. According to longtime New York diarist George Templeton Strong, what he and Fish and several others had been trying to do was to “take charge of polite society, regulate its institutions, keep it pure, and decide who shall be admitted….”

Such efforts proved unable to cope with the surge of new wealth during and after the Civil War, so that the 1880s became the crucial period for the establishment of a sufficiently inclusive yet durable upper class. Local cultural institutions played a notable part, as they had earlier, with such newer organizations as the Metropolitan Opera and the Metropolitan Museum of Art expressing the energies of the newer upper class. Among Sheldon’s owners, A. T. Stewart was one of the biggest early donors to the Metropolitan Museum, sugar refiner Robert Stuart was active on the organizing committee and railroad president John Taylor Johnston became the museum’s first president. The Metropolitan Opera provided an even greater opportunity for new families to shine, for box ownership gave conspicuous places to such new arrivals in New York as H. Victor and Florence Newcomb and Richard T. and Melissa Wilson and to other rapid risers in society, such as George and Juliet Kemp and Bradley and Cornelia Martin.

Parallels were to be found in such other cities as, for instance, Philadelphia, where banker James L. Claghorn, retired from active business since the outbreak of the Civil War, took over leadership of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The Pennsylvania Academy, Philadelphia’s preeminent art museum since soon after its founding in 1807, moved into its new home, designed by Frank Furness, a few years after Claghorn became its president in 1872. Claghorn, one of America’s foremost collectors of etchings and engravings, worked on the Academy’s board with another Sheldon subject, distiller and wine importer Henry C. Gibson, and the two made substantial donations to the collections. Rising to challenge the eminence of the Academy was the Pennsylvania Museum of Art, begun only in the late 1870s as a result of the great Centennial Exhibition. Gentlemen such as Claghorn and Gibson kept the museum at arm’s length, but it received a solid foundation in the fine arts from the mid-1880s gifts made by still another Sheldon owner, Clara Jessup Moore.

In Chicago too, men of newer wealth built up a new museum to help symbolize their own economic and cultural achievements. For Chicago, the Great Fire of 1871 gave particular impetus to new beginnings and the Board of Trustees that set out to reestablish the Academy of Design soon founded instead a new Academy of Fine Arts, which in 1882 became The Art Institute of Chicago. Active on the Board in all these stages was Samuel M. Nickerson. Born in Massachusetts, and later clerking in his brother’s store in a Florida town in the early 1850s, Nickerson had moved to Chicago in 1857 and by the time of the fire was president of both the First National Bank and the Union Stockyards National Bank. By the time Sheldon presented his home (nos. 103 & 104), Nickerson’s art collection was considered one of the largest in the West, a collection he ultimately donated to the Art Institute.

Art, both in the home and in museums, had long been a way for an upper class to combine personal pleasure with a declaration of social status. To this and other traditional expressions of rank, the newly enlarged upper class of the 1880s brought several innovations intended to make clear lines of social distinction and establish homogeneity. Residential patterns, for instance, took on a new significance as the 1880s brought the rise of the upper-class suburb, a planned community with firm restrictions on who could buy and build. In Artistic Houses, Sheldon limited himself primarily to distinctly urban homes, but Short Hills, New Jersey, the home of William I. Russell and Franklin H. Tinker, typified the new suburban pattern. As Sheldon noted, “six years ago the place was a wilderness of forest-growth,” while when he visited it contained three dozen attractive year-round homes and all the amenities of “a beautiful village, without the nuisances of a village.” In other words, it had music hall, church, club, stables and greenhouses but “no stores, no unsightly sheds, no country ‘bar.’” Russell, a broker in metals who late in life wrote an autobiography, moved into his new home, “Redstone” (no. 74), in 1882, soon made friends with Tinker, a fellow book collector, and found life in the small, self-contained suburb “all that we would have it—peaceful, happy, contented.” Given the small size and homogeneous character of the community, social activity involving all the residents soon became a hallmark of Short Hills life. Russell found that “the frequent pleasant little dinner-parties of four to six couples, where bright and entertaining conversation was general,” made his new home the key to “serenity and delight.” Bringing together the whole little community were “enjoyable amateur dramatic performances, followed by light refreshment and a couple of hours’ dancing.” Now and again there would be a special community event, as when Russell hosted a ball to open his new carriage house and stable. The stable itself was transformed into a ballroom, with floral horseshoes, a bronze jockey and coaching pictures for decorations, the orchestra upstairs around the open hay doors, and guests receiving with their dance cards “a sterling silver pencil representing the foreleg of a horse in action, the shoe being of gold.”

A complementary innovation, drawing the well-to-do out of the city in an organized and exclusive way, was the country club, also a new phenomenon of the 1880s. Such clubs, springing up on the outskirts of most Eastern cities in the decade, brought together the rising interest in sport, such as riding, coaching and tennis, with the growing concern for social exclusiveness. The Country Club, founded in Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1882 is commonly considered the first of its kind, and one of Sheldon’s Boston couples, John L. and Isabella Stewart Gardner, were active members. Coaching with two, three or four horses and a variety of conveyances became a particular interest of the Gardners; leading a line of coaches from Boston out to The Country Club gave Isabella Gardner an opportunity to cultivate and display flamboyance. Similarly, in Washington, Nicholas Longworth Anderson was writing to his son in the 1880s that he and his wife were helping to establish a similar country club, perhaps inspired in part by Gardner, “one of my most intimate friends.” The Andersons found their new club a welcome opportunity for recreation and a new vehicle for the social life that included frequent entertainment of American political leaders and European diplomats.

Club and suburb were important not only for who was included and accepted, but for who was excluded. In many cases no doubt a man of wealth found himself left out because others did not care for his personal habits, his business practices or his family. One type of exclusion by group identity was becoming more pronounced and formal in the 1880s—anti-Semitism. Institutionalized anti-Semitism was relatively easy to bring about when one was forming a new club or residential area, but the practice received its most well-publicized beginning in a long-established place of public accommodation. In the late 1870s, one of Sheldon’s owners, Judge Henry Hilton, had recently begun effective management of the A. T. Stewart millions and one of his responsibilities was the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga, New York, a summer retreat popular with the wealthy. When Hilton, in 1877, refused rooms to Joseph Seligman, a prominent New York Jewish banker, he incurred a flurry of denunciation, but Hilton’s anti-Semitic policies soon caught on and set the pattern for an increasing number of upper-class institutions in the 1880s.

While the exclusive suburb and the country club offered upper-class definition to separate local groups, the prestigious boarding schools begun in the 1880s were designed in part to cultivate links between elites in different cities, to help bring about a self-conscious national upper class. A few of what became socially selective boarding schools had been founded earlier, notably Phillips Exeter, Phillips Andover and St. Paul’s. They had been day schools, educating a local clientele at a time when many wealthy families hired tutors to educate their children at home. The shift of the older schools toward boarding students drawn from throughout the Northeast mirrored the character of the new schools founded in the 1880s expressly to educate a national elite. Foremost among the new schools was Groton, founded in 1884 by Endicott Peabody to help train gentlemen. Learning was important, but it was also essential “to have good manners and be decent and live up to standards.” On his first small Board of Trustees, Peabody enlisted the vital support of two of Sheldon’s householders, Trinity Church’s pastor Phillips Brooks and prominent Episcopal layman and banker J. Pierpont Morgan. As one of his first two teachers, Peabody hired William A. Gardner, nephew of John L. Gardner and raised in the Gardner home.

Such formal institutions were important ways of organizing society, but the home itself remained the key to definition and cultivation of a recognizable and responsible upper class. Clubs and schools affected people only at a particular time in their lives or through a specialized interest, and for the most part their activities included only men. Invitation into the home was the one act that could touch all aspirants to inclusion in Society. Such an invitation was first an opportunity and a testing and later a confirmation that one belonged.

Proper behavior in the home was not something that could be taken for granted, for the rapid increase in the number of wealthy Americans meant that there were many men and women who believed they ought to be invited into upper-class homes but who were unsure how to behave once they got there. They solved the problem with a book. The fictional Silas Lapham, for instance, as soon as his family had been invited to dinner by the long-established Coreys, immediately bought an etiquette book to save himself from obvious blunders.

Lapham had innumerable real parallels, as the great popularity of such books in the 1870s and 1880s demonstrated. Of these the most widely read was Sensible Etiquette of the Best Society by one of Sheldon’s Philadelphia house owners, Clara Jessup Moore. Moore first published the book under a pseudonym in 1878, and it soon went through 20 editions. Having inherited some $5 million on her husband’s death in the same year, Moore had a solid place among the wealthy in Philadelphia, but her father had suffered business failure when she was young and wealth had come only in the 1850s, as a result of a partnership between her father and her husband in paper manufacturing. Moore was perfectly aware of at least a part of her market, giving the name “Madame Newrich” to one of the recipients of instruction in her book. Moore assured her readers, however, that they need worry about no inherent inferiority in manners. No one had natural or inborn manners, which were “only acquired by education and observation, followed up by habitual practice at home and in society.” So there was no reason for men or women to fear betraying their origins, as long as they applied themselves to learn the intricate and rigid code Moore described.

Fig. 9. Clara Jessup Moore house, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

As in the other efforts to define a stable upper class, etiquette too required fixed order. Moore recognized that mobility and economic growth made a fixed code of manners difficult to achieve, but American heterogeneity made such a code all the more necessary because friction and conflict could be avoided only as a result of “our obedience to the laws of that etiquette which governs the whole machinery, and keeps every cog and wheel in place, and at its own work.” People had to know what to expect of each other and only agreed-upon manners could prevent serious misunderstandings or “rudenesses suspected where none are intended.” Writing after the upheavals of the Civil War and of the depression of the 1870s, Moore hoped that America had settled into a pattern that would make possible fixed manners. Otherwise, if “the first principles of social intercourse” are “violated at the foundations, the entire structure of society becomes insecure.”

Quite apart from such goals of national stability, Moore also knew that people going through her own earlier experiences would feel more comfortable in the homes of the Claghorns and Gibsons and the like if they knew just what to do. She would tell them, in chapter after chapter of specific instruction. Suppose a reader found him- or herself in one of the dining rooms Sheldon pictured, exactly the kind of situation Silas Lapham worried about:

As soon as seated, remove your gloves, place your table-napkin partly opened across your lap, your gloves under it, and your roll on the left side of your plate. If raw oysters are already served, you at once begin to eat; to wait for others to commence is old-fashioned. Take soup from the side of the spoon, and avoid making any sound in drawing it up or swallowing it. Vegetables are eaten with a fork. Asparagus can be taken up with the fingers, if so preferred. Olives and artichokes are always so eaten.

To master such rules and go on to host such social events was no trivial accomplishment, Moore and other etiquette authorities argued. The person who could “make her parlor a rallying-point for nice people is doing a great public service,” according to M. E. W. Sherwood, author of Manners and Social Usages. She and Moore agreed that a society leader was a power for good, by refining and elevating standards of behavior, checking the pretensions of the vulgar and the immoral, and raising to influence those with genuine merit in a country where all sorts of people were mixed together. The home in this way was the key to decency, honesty and stability in society.

Moreover, the home gave women in particular an influence otherwise difficult to exercise. Women of wealth recognized that the lack of household work gave them no practical importance in the home. As adults in the 1880s, most such women had not enjoyed a substantial formal education and they did not expect important roles in the public institutions of their lives, such as the church. They faced a dilemma well described by a fictional young woman in a popular novel of the decade, Ruth Cheever in Edgar Fawcett’s A Gentleman of Leisure. As Cheever explained to the novel’s hero, “A woman gets no satisfaction, in this age, out of the most legitimate discontentments. She has a choice between two extremes, and that is all. She must either consign herself to frivolities, or else be satirized as a prig, a person ‘with views.’ And in either case she is satirized, 1 find, all the same.” Moore and Sherwood offered women a way out. They could transform those social activities that others might label frivolous and infuse them with moral purpose. “What do women want with votes,” Moore asked, “when they hold the sceptre of influence?” This influence, she made clear, was not just that traditional influence of moral motherhood, for it did require rigorous formal education, but it was a use of domestic position well beyond the benefit of one’s own family to achieve goals that men alone could not. By setting a standard in society and organizing it so as to make social distinction both clear and desirable, women could see to it that members of the American upper class “really fulfill certain important functions, that they really offer a higher standard of elegance and culture, that they really encourage an improvement in manners, and stimulate the growth and spread of refined taste.”

The ordinary dinner party or tea naturally offered opportunities for working toward Moore’s ends, but what most caught the public’s eye was the much more conspicuous effort to organize one unified upper class, as seen in the great balls of the 1880s. Probably the single most important event of this sort took place not in one of the homes that Sheldon described, but in that of Mr. and Mrs. W. K. Vanderbilt, son and daughter-in-law of Sheldon’s William H. Vanderbilt. The younger Mrs. Vanderbilt’s ball to open her new Fifth Avenue home on March 26, 1883, marked the at least limited acceptance of the newer aristocracy by the older, symbolized by Mrs. William Astor’s attendance. The desire of Mrs. Astor’s daughter Caroline to be invited to the ball had supposedly been the principal reason for the mother’s social acceptance of the younger Mrs. Vanderbilt. The amalgamation of older and newer aristocracy would soon be made more vivid by Caroline’s marriage to another ball guest, Orme Wilson, son of the Richard T. Wilsons who had been making such a social splash in New York since their arrival from Georgia after the Civil War.

A more substantive indication that old differences could be overcome in the interest of upper-class unity was the presence at the same ball of two other Sheldon house owners, Mrs. Hamilton Fish and Mrs. William H. Vanderbilt. To her own generation, Julia Kean Fish, even more than Mrs. Astor, represented the most rigorous exclusiveness of the old Knickerbocker elite. Edith Wharton and M. E. W. Sherwood, for instance, both singled her out as an example of the high moral tone and seriousness of the old-school social leader. Her ability to live up to expectations had been amply demonstrated when she set the social standard for the Grant administration, in which her husband was Secretary of State. Maria Louisa Kissam, on the other hand, had been socially unacceptable even to the self-made Cornelius Vanderbilt when his son married her at the age of 19. The senior Vanderbilt virtually exiled William H. and Maria to a farm on Staten Island, and Mrs. Vanderbilt never felt comfortable with the position in New York society to which her wealth and home entitled her. That she and Mrs. Fish could converse readily at her daughter-in-law’s ball indicated a coming together of the urban upper class such as the new boarding schools, for instance, were trying to achieve or that Boston minister Phillips Brooks was working for in his church.

The junior Mrs. Vanderbilt’s guest list included a variety of representatives of the older and newer upper classes. Among other Sheldon home owners were former President and Mrs. Grant, friends of both the Fishes and the senior Vanderbilts, and J. Coleman and Charlotte Drayton, she the daughter of Mrs. Astor. Bradley and Cornelia Martin no doubt surveyed the ball for usable ideas in their own beginning social campaigns. Others participating in the lavishly costumed quadrilles or observing included Mr. and Mrs. Robert Goelet, who enjoyed one of New York’s older real-estate fortunes, and Mr. and Mrs. John T. Johnston. Frederic W. Stevens, on the board of a half-dozen banks and insurance companies and another half-dozen museums and libraries, was present with his wife. From out of town came Mr. and Mrs. George P. Wetmore, owners of a Newport “Artistic House,” but thoroughly at home in New York social and cultural activity.

The Vanderbilt ball, which according to the New York Tribune “equalled, if it did not excell, any similar entertainment ever given in this city,” marked the beginning of a decade of flamboyant entertainment. Grand costume balls became a standard method either of claiming or of consolidating social position and the most elaborate were noted as the pinnacle of social activity for decades before and after in their respective cities. Such, for instance, was the “Mikado Ball,” hosted in 1886 in Chicago by another of Sheldon’s home owners, Marshall Field (nos. 55 & 56). Some 500 guests attended in oriental costume and the reputed $75,000 expense helped make the Field ball a landmark event in late nineteenth-century Chicago.

The great balls, with their published guest lists, together with the appearance of the Social Register late in the 1880s, might be thought to have achieved the goal of a fixed, defined Society. In New York at least, such methods of selection still produced too large a group, so further refinement seemed necessary, and in 1888 society organizer Ward McAllister first used the term “the Four Hundred” to describe the core group, the most elect. The term supposedly derived from the number of guests who could be entertained comfortably in the ballroom of Mrs. William Astor, foremost of the three principal society hostesses in New York. The other two, Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt and Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish, were daughters-in-law of Sheldon householders.

Not until 1892, when McAllister agreed to an interview with the New York Times, did the public get a reliable list of the Four Hundred by name, and then it included fewer than 300 individuals. The list showed that the core of Society was much as the interested public had come to think, a group of men and women who devoted their lives primarily to entertainment of themselves and each other. Few of the men had an active occupation, but had lived on family income for most of their lives, and most had used their leisure in club life, yachting and the like rather than in museum trusteeships or some other form of public service. Among Sheldon’s house owners, McAllister’s list did include former Rhode Island Governor George P. Wetmore and his wife, long mainstays of New York society. Egerton Winthrop was more representative. Mr. and Mrs. Robert Goelet, owners of one of the most magnificent steam yachts afloat, were included, as were those constant party givers, Bradley and Cornelia Martin. The Richard T. Wilsons were by now well established at the center of New York society through their son’s and daughters’ marriages into the Astor, Goelet and Vanderbilt families. By the end of the 1880s, then, Society leaders had accomplished what they set out to do: make clear the composition of the accepted American upper class.

THE EFFORT TO ACHIEVE LASTING ORDER IN AMERICAN SOCIETY

The Four Hundred made up one small but well-publicized segment of wealthy America. The ever more lavish entertainments sponsored by Vanderbilt and Fish heirs and others increasingly captured public attention by the end of the 1880s and gave a false sense of frivolity to upper-class activity. In one respect, however, the Four Hundred did show a pervasive current in upper-class concern—the determination to create a lasting order, to impose unity where there had been fragmentation. The decade of the 1880s saw the ripening of a generation of wealthy men and women who seized the opportunity to gain firm control over the American economy in order to make permanent what they saw as the necessary conditions for continued prosperity and social stability and, based on those two factors, the flourishing of American culture.

At the opening of the decade, such men and women looked back on a period marked by upheaval, disorder and tension in many areas of life. Political life had been tarred by corruption and scandal in the Grant administration, although the President himself escaped with his reputation for personal honesty intact. The panic of 1873 and subsequent depression had revealed instability in economic expansion. A by-product of the depression had been bitter conflict between workers and employers, most vividly seen in the great railway strikes of 1877. Continued dissent over race relations and the federal government’s responsibility for civil order in the South remained a source of friction through much of the decade. Corporations seemed plagued by guerrilla warfare waged against each other, as in the railroad skirmishes launched by the Erie Railroad, or by internal weakness that brought bankruptcy after the 1873 panic. In all of these areas and others, those men who survived the 1870s with wealth and power intact saw patterns of instability and disorder that they were determined to correct. They would impose their control in crucial areas and launch a period of calm which would not only profit themselves but make possible widespread prosperity and cultural advance. For a time they succeeded, and the 1880s proved to be the last period in which men of wealth enjoyed not only such relatively unchallenged power in America but also so much public acclaim. In most of these achievements, Sheldon’s householders were at the forefront.

For many of Sheldon’s owners, men who were in the midst of creating their own fortunes, business success was, of course, the focus of their lives and their activities give little sign of larger social concerns. For some, such as silk manufacturer Knight D. Cheney, woolen maker Swits Condé, or another wool manufacturer, David L. Einstein, concentration was on rescuing and strengthening a family business. Each of these men found himself fully busy in the 1880s saving and expanding a business, founded by father or uncles, that had slipped in the depression of the 1870s and now needed a newer, firmer hand. Sheldon’s group also included several who had started their own business, devoted their lives to them, and saw the prosperity of the 1880s essentially as a chance for personal gain. Irish immigrant George Kemp, who had arrived in New York in 1834 at the age of eight and gradually built up a major drug- and perfume-manufacturing and wholesaling firm, and metals broker William I. Russell, who had started with one clerk and a tiny office in 1871, concentrated on making the most of the expanding economy. For Russell, increased prosperity meant opportunities to get rid of small customers and concentrate on large ones. The resulting satisfaction and continued focus on one’s own business, with recognition simply among one’s business associates and friends, was characteristic of many of Sheldon’s owners.

While men like Kemp and Russell remained inconspicuous, strict devotion to one’s own business became part of Marshall Field’s increasing reputation. If men of wealth had any obligation to society, Field saw that responsibility as pure and simple efficiency in business. Find products that people needed and sell them at a uniform, moderate price; the man who could do that well had fulfilled his most important social role, in Field’s view. Starting in retail trade in Chicago in the mid-1850s, Field had already gone through several partners by the mid-1880s and was well known for taking no active part in Chicago politics and giving little attention to any charitable activities. Field was becoming a recognized model for the strict, no-frills businessman who never borrowed or speculated, who kept all transactions on a cash basis, who held all his associates to a strict meeting of obligations, and who spared no energy from the affairs of his own firm. In this light Field embodied the virtues that men of wealth respected, but he was an inadequate model for an upper class that welcomed wider responsibilities.

Similar to Field in some respects, seeing his business itself as his main form of public service for a time, was John Taylor Johnston. Johnston entered railroading by means of the practice of law and helped consolidate several New Jersey lines into the Central Railroad of New Jersey, of which he became president in 1848. Like Field, Johnston saw economical provision of an essential service as his main contribution to society, but he expanded that idea somewhat to a hope that his railroad could be a particularly safe and attractive example. Accordingly, Johnston used his control to eliminate grade crossings wherever possible, to erect well-designed stations and to surround his stations with landscaped parks. Though focusing clearly on the railroad business, Johnston accepted responsibilities other than efficient service.

If running one’s own store or railroad well was the focus for some of Sheldon’s owners, others were gaining a reputation for attempts to dominate a whole segment of the economy. To such men, the lesson of the 1870s had been that economic instability resulted from fragmented industries in which too many firms lacked the resources to survive temporary setbacks. The solution was consolidation, with major firms buying out and absorbing competitors while at the same time gaining control over the suppliers and distributors of their product. For Americans at the time the greatest and most controversial example of this effort to impose order and stability was the Standard Oil Company and, except for its principal founder John D. Rockefeller, no person had played so large a part in Standard Oil’s success as one of Sheldon’s house owners, Henry M. Flagler.

Flagler, in Bellevue, Ohio, had dealt with Rockefeller in Cleveland as early as 1850, when both were buying and selling grain. After an unsuccessful venture in salt in Michigan, Flagler moved to Cleveland and, in 1867, entered into a partnership with Rockefeller and others in oil refining. At the time, the petroleum industry was made up of innumerable small, independent drillers, refiners, tank-car companies, retailers and the like. Flagler and Rockefeller set out to bring order to what they saw as chaos. They concluded that they could enlarge the market and lower the price of petroleum products, ensure stability of supply and make fortunes for themselves if they eliminated the waste and duplication of competition, so for some 15 years they persistently extended their control and discipline over the industry until, by the time they formed the final Standard Oil Trust in 1882, they controlled at least 90 percent of American refining.

Flagler’s work in Standard Oil was probably the best example among Sheldon’s group of the characteristic determination to impose order and set a pattern expected to last, but other house owners were equally active in other areas of the economy, if not as successful as Flagler. In meat packing, Herman 0. Armour worked with several brothers in Armour and Company to consolidate an activity earlier characterized by many small packers. Another food-processing field, sugar refining, experienced the very successful amalgamating efforts of the American Sugar Refining Company, in which the Havemeyer family, represented in Sheldon’s collection by William F. Havemeyer, played a significant role. Railroading was one of the country’s most active fields of consolidation and two of the most well-publicized entrepreneurs of the 1880s, Henry Villard of the Northern Pacific and William H. Vanderbilt of the New York Central system, were among Sheldon’s owners.

While some consolidators were able to rely largely on their own resources, banking houses were heavily involved in much of what went on. If the achievement of order and stability through the elimination of competition and the strengthening of dominant firms was a hallmark of the 1880s, then already playing a leading role was another Sheldon figure, investment broker J. Pierpont Morgan. From the late 1860s on, Morgan had built a career on the identification of his own fortunes with the elimination of weak or erratic firms in major industries, especially railroading. Morgan sought to put out of business those he saw as working only for short-term gains and to put industrial activity into the hands of those who would ride out economic fluctuation. In 1879 Morgan helped William H. Vanderbilt maintain the value of New York Central stock by placing a large block of shares directly with English investors, an act that particularly solidified his reputation as a man of both great ability and great concern for stable control.