A defeat for the Royal Navy in the South Pacific, and then an emphatic victory in the South Atlantic

At 6.18 p.m. on 1 November, off the coast of central Chile near the port of Coronel, Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock, a bachelor Yorkshireman with a passion for foxhunting, signalled to the distant HMS Canopus, a pre-dreadnought battleship sent by the Admiralty to reinforce his South Atlantic cruiser squadron: ‘I am now going to attack enemy.’

So began, wrote Winston Churchill, first lord of the Admiralty, ‘the saddest naval action in the war. Of the officers and men in both the squadrons that faced each other … nine out of ten were doomed to perish. The British were to die that night: the Germans a month later’ (The World Crisis, vol. 1, 1923).

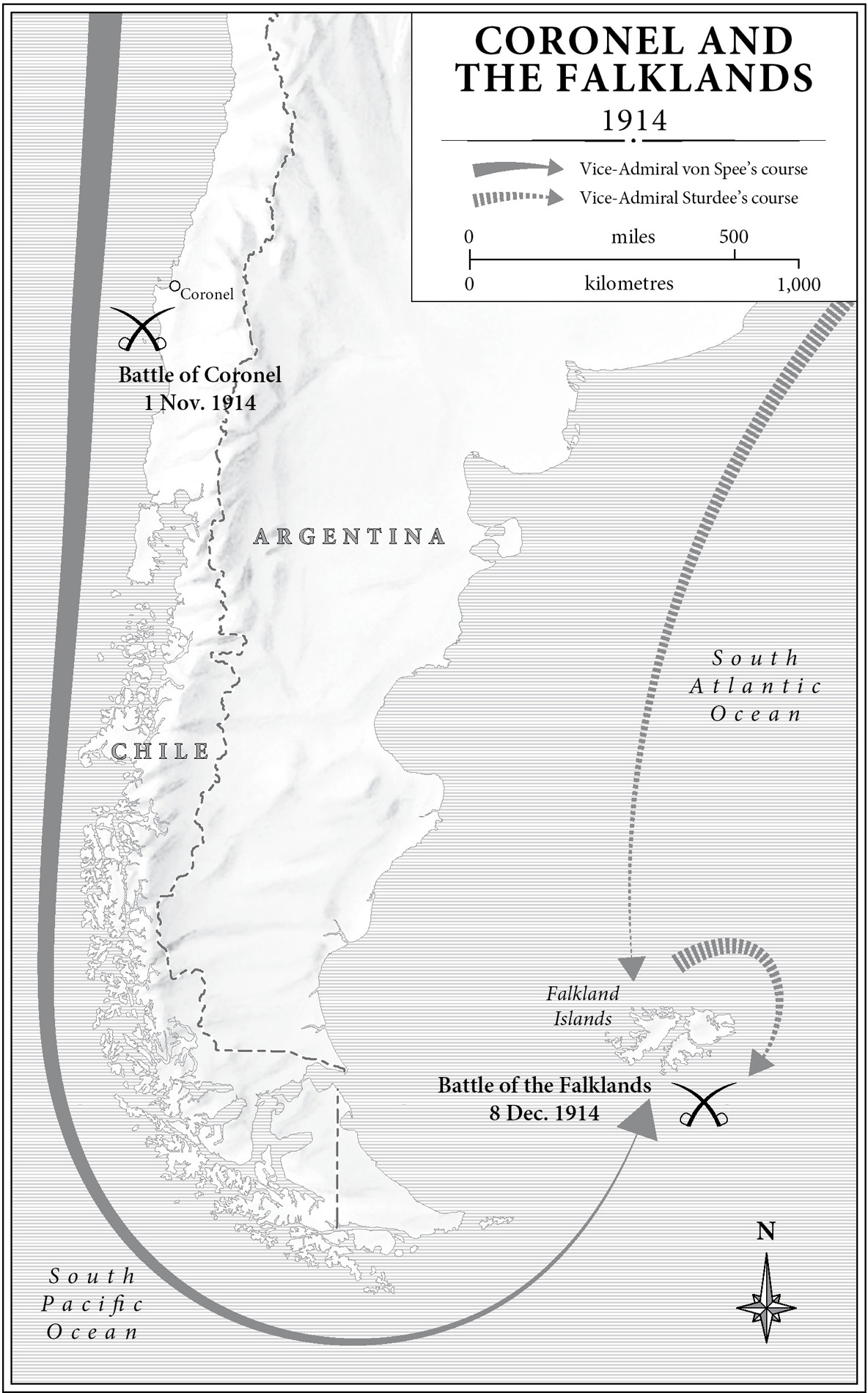

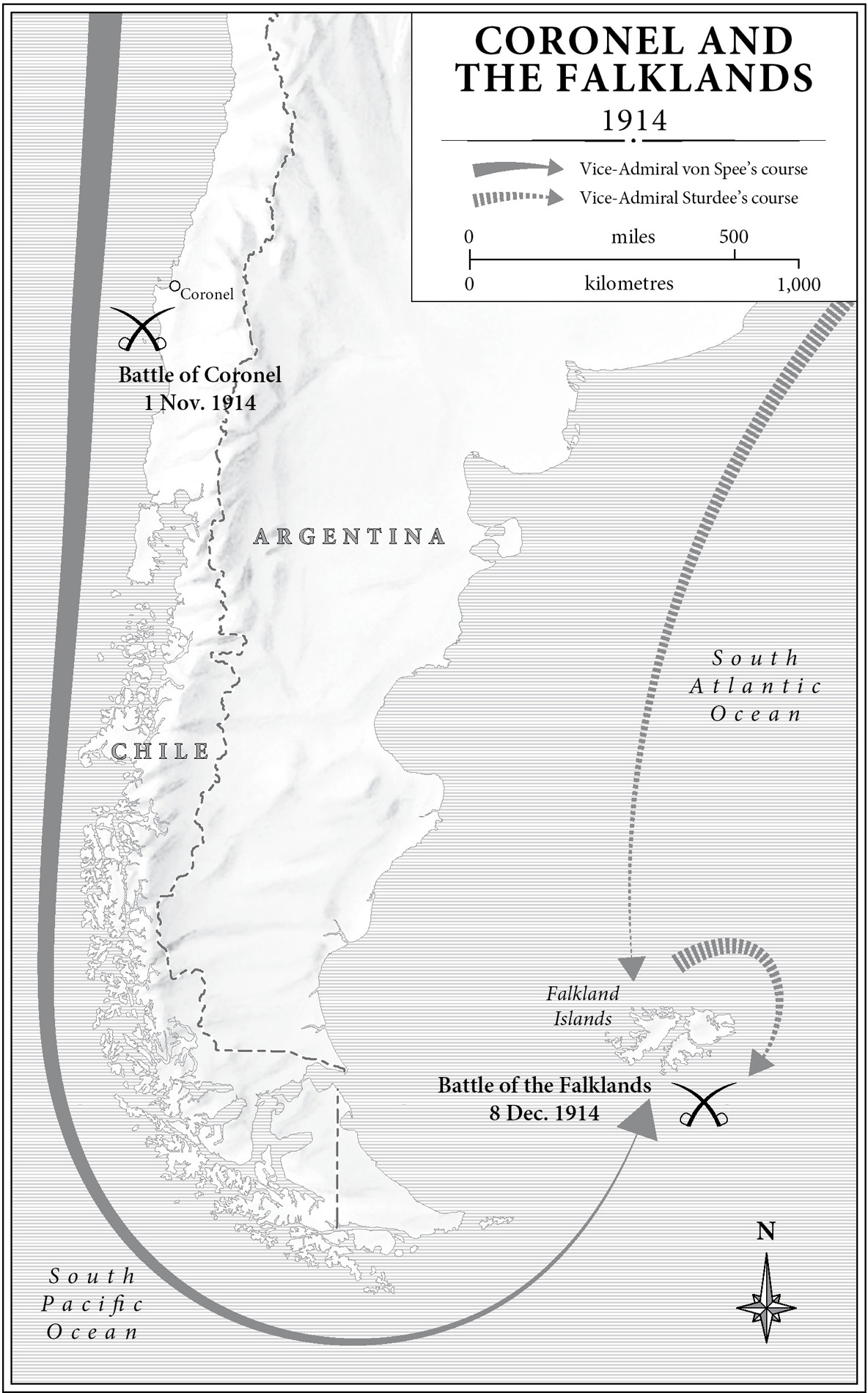

The Battle of Coronel, still the subject of controversy, was the result of faulty intelligence, misunderstanding and miscommunication. After commerce raiding in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, Vice-Admiral Maximilian Graf (Count) von Spee’s East Asia squadron had turned its attention to southerly waters. The squadron comprised mainly light cruisers, some of which were detached for independent action – notably the Emden, which in September had bombarded Madras – but had two modern armoured cruisers, the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, crewed by the best men of the German fleet. In mid-September Cradock was told to prepare to meet Spee if he came into South American waters. However, his own squadron consisted of elderly cruisers manned largely by reservists, and whereas Scharnhorst and Gneisenau could each dispose eight 8-inch guns, six of which could fire on either beam, Cradock’s flagship, HMS Good Hope, had but two 9.2-inch guns that could match their range, while his second cruiser, Monmouth, carried only nine 6-inch guns that could fire on the beam. The Admiralty, judging that not a single dreadnought-class battle-cruiser could be spared from the Grand Fleet, which was keeping the German High Seas Fleet penned up in Wilhelmshaven, sent south instead the elderly battleship Canopus. Her four 12-inch guns could easily deal with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, but she lacked speed – 15 knots compared with Good Hope’s 23.

In late October, having intercepted signals from the cruiser Leipzig, Cradock concluded that she was the only one of Spee’s ships to have reached Chilean waters, and so took the armoured cruisers Good Hope and Monmouth, the light cruiser Glasgow and the armed merchant ship Otranto round Cape Horn to intercept her, leaving the slower Canopus to escort his colliers. Glasgow scouted ahead to Coronel, where on 1 November, instead of just Leipzig, she found Spee’s entire squadron.

In the coming darkness Cradock could have withdrawn to the cover of Canopus’s 12-inch guns 300 miles to the south, but he decided to stand and fight. Not the least of his reasons was that a fellow rear-admiral, Ernest Troubridge, was facing court martial for letting slip the cruisers Goeben and Breslau in the eastern Mediterranean the month before.

According to Glasgow’s log, ‘the British Squadron turned to port four points together towards the enemy with a view to closing them and forcing them to action before sunset, which if successful would have put them at a great disadvantage owing to the British Squadron being between the enemy and the sun’. However, Spee used his superior speed to overcome the dazzle, putting his ships on a parallel course south. Within an hour Cradock’s ships were silhouetted against the afterglow of the sun, which had now dipped below the horizon, while his own were scarcely visible against the dark background of the coast. At seven o’clock he opened fire.

The sea was high, adding to the difficulties the Good Hope’s and the Monmouth’s gunners faced, for their 6-inch guns were on the main deck, while the Germans’ were on the upper. Scharnhorst’s third salvo put one of Good Hope’s 9.2-inch guns out of action, and shortly afterwards she exploded with the loss of all hands, including Cradock and his beloved terrier Jack. Monmouth, though holed and listing badly, refused to surrender and was shelled at close quarters by the cruiser Nürnberg until she too sank without survivors. Otranto, unarmoured and having only 4.7-inch guns, was incapable of taking part in the action, and managed to use her 18 knots to get away. Glasgow remained pluckily in action until darkness overcame her, when she too managed to escape. In all, the British had lost 1,654 sailors in less than an hour, the Germans none.

Coronel threw the Admiralty into a rage, for not only was it the Royal Navy’s first defeat at sea in more than a century, it left Spee in command of South American waters and with a wide choice of alternatives. But Spee himself had doubts. When the German community in Valparaiso, where he had put in after the battle, pressed congratulatory bouquets on him, he replied: ‘They will do for my funeral.’

This time the Admiralty spared no measures. While Churchill arranged for the Japanese navy to cover the South Pacific, the 73-year-old first sea lord, Admiral of the Fleet Lord (Jacky) Fisher, who had been brought out of retirement days earlier following the enforced resignation of the German-born Prince Louis of Battenberg, detached the dreadnought battle-cruisers Inflexible and Invincible from the Grand Fleet. After hasty refit at Devonport, these raced south under command of the square-jawed Vice-Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee and, having rendezvoused with Rear-Admiral Archibald Stoddart’s mid-Atlantic cruiser squadron at the Abrolhos Archipelago off Brazil, reached Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands on 7 December. Here they found Canopus undergoing repair to her boilers, but her guns ready for action, and began at once to coal.

It was not a moment too soon, for the day before Spee had sailed through the Straits of Magellan intending to destroy the signal station at Stanley. At about eight o’clock on 8 December his leading armoured cruiser, Gneisenau, with his younger son Heinrich on board, came in sight of Sturdee’s guardship. ‘A few minutes later a terrible apparition broke upon German eyes,’ wrote Churchill. ‘Rising from behind the promontory, sharply visible in the clear air, were a pair of tripod masts. One glance was enough. They meant certain death.’ For only dreadnoughts had tripods – and eight 12-inch guns apiece.

But Sturdee’s battle-cruisers, still coaling, could not immediately raise steam, and it was Canopus, beached on the mudbanks, that opened fire first as Gneisenau turned away to rejoin the main body of the squadron. Soon all five of Spee’s ships were making full steam east then south, pursued by the cruisers Glasgow, Kent and Carnarvon, but it was not until nearly ten o’clock that Invincible and Inflexible could give chase. However, both ships, fresh out of dry dock, had a 5-knot advantage over Spee’s, and in three hours closed to within 17,500 yards of Leipzig and opened fire. Spee now ordered his light cruisers to turn south-west, while Scharnhorst and Gneisenau turned north-east to cover their retreat. They opened fire half an hour later and scored a hit on Invincible, though the shell burst harmlessly on the belt armour.

British gunnery was poor at first, scoring only four hits out of more than 200 rounds fired, largely owing to the copious quantities of smoke generated. Sturdee therefore decided to put distance between the opposing squadrons and, as in Nelson’s day, to seek the weather gauge, though not for steerage but to get upwind of the smoke. But Spee closed again to 12,500 yards to enable him to use his 5.9-inch guns, and firing continued for some hours, both sides now troubled by poor visibility. Damage to both Scharnhorst and Gneisenau mounted, however, while that to Inflexible and Invincible was negligible. Scharnhorst ceased firing at four o’clock and capsized a quarter of an hour later with not a single survivor, Spee going down with his flagship. Gneisenau was pounded for another hour and a half by both battle-cruisers, which had closed to just 4,000 yards, until her captain opened the sea-cocks and she too capsized, the British ships picking up 176 men from the freezing sea. Lieutenant Heinrich von Spee was not among them.

Sturdee’s cruisers, which had given chase to the lighter ships, overtook and sank the Leipzig later that evening, pulling just eighteen sailors from the water. HMS Kent had earlier caught and sunk the Nürnberg, having exceeded even her design speed. Nürnberg had refused to surrender, and as she foundered by the head, a huddle of her remaining crew on the rising stern could be seen waving the German flag. All but seven of her complement of over 300 perished, including Lieutenant Otto von Spee, the admiral’s elder son.

Only the Dresden escaped, but she was cornered three months later in Chilean waters, where she too was scuttled and her crew interned; they included Lieutenant Wilhelm Carnaris, the future chief of Hitler’s military intelligence service, the Abwehr. In December 1939 the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee, named in honour of the victor of Coronel, would herself be scuttled in South American waters after a brilliant affair of gunnery and deception by Commodore Henry Harwood’s cruiser squadron at the Battle of the River Plate, off Montevideo, when once again Churchill was first lord of the Admiralty.

With the fortuitous wreck of the Karlsruhe off the West Indies in November, the cornering of the Königsberg in German East Africa and the destruction of the Emden by HMAS Sydney in the Indian Ocean, by the middle of March 1915, as Churchill wrote, ‘no German ships of war remained on any of the oceans of the world’. The consequences of their exclusion, he noted, ‘were far-reaching, and affected simultaneously our position in every part of the globe’.

From now on the Germans’ war against merchant shipping would have to be waged by submarine – activity which would do so much to bring the United States into the conflict – or else the High Seas Fleet would have to break out of Wilhelmshaven. This they would not try until the middle of 1916, when at the Battle of Jutland the Royal Navy forced them back into their North Sea haven for the rest of the war.

While the Royal Navy’s distant drama of tragedy and revenge was being played out, the fighting at Ypres on the Western Front had become very bloody indeed as the Germans made desperate attempts to break through to capture the Channel ports. Reservists of every type, as well as dismounted cavalrymen and Indian troops, many still in their tropical uniforms, were thrown in to hold the line. On 6 November, Captain Arthur O’Neill of the 2nd Life Guards became the first MP (for Mid Antrim) to be killed – the first of nineteen. His youngest son would be prime minister of Northern Ireland in the 1960s. Casualties at ‘First Ypres’ to 22 November, the close of the qualifying period for the medal known colloquially as the Mons Star, were some 60,000.

Fighting on the Eastern Front, though, remained fluid. Having managed to defeat an Austro-Hungarian offensive in Galicia and a German attempt to take Warsaw, in early November Russian forces began a counter-offensive into Silesia. After heavy losses, however, both sides accepted they had gone as far as they could, and in early December the Russians withdrew to a new and stronger line closer to the Polish capital.

Meanwhile, in Mesopotamia, the British were striking the first blow against the Turkish army. On 7 November the 6th (Poona) Division of the Indian army landed at the mouth of the Shatt al-Arab waterway to secure the Persian oilfields, taking Basra a fortnight later. It would be another three and a half years, however, before the Turks were finally ejected from what is now Iraq.