The area that became the Colorado Territory began as a land white Europeans usually only passed through on their way to somewhere else—“fly-over” country might ben the term used today. That quickly changed when gold was discovered along the Front Range of Colorado, a mountainous area located in the central part of the territory. A few fur traders were replaced by miners, and merchants, businessmen, farmers, and ranchers arrived. The lure of easy riches had a way of making the idea of Manifest Destiny more palatable to those who deigned to consider its ramifications. Trails and stagecoach lines veered toward central Colorado and railroads would soon be on the way. Denver was on the road to becoming a metropolis of the mountains. Unfortunately for them, the Indian tribes refused to quietly exit the stage.

The previously sporadic fighting increased when gold-seekers entered the region. Up in Minnesota in 1862, the Sioux had fought back, killing as many as 600 white settlers and soldiers. The military retaliation spilled over into the Dakotas, turning once-neutral tribes there into enemies. The turmoil and fighting spread farther west and south. In 1863, the US Army conducted major campaigns in the Dakotas, while in Colorado, Governor John Evans and Colonel Chivington were wringing their hands worrying that the war would spread to their domain. Rumors of raiding abounded.

In November 1863, Robert North, a white man living with the Arapahos, gave the governor a shocking report: Bands of Comanche, Apache, Kiowa, Arapaho, Sioux, and Cheyenne had pledged to each other to go to war with the whites in the spring of 1864, as soon as they could get enough ammunition and guns to do so. Since Robert North had an Arapaho wife, the Indians had asked him to join the uprising, but he had demurred. “I am yet a white man,” he replied, “and wish to avoid bloodshed.”

Governor Evans sent the alarming news to Commissioner of Indian Affairs William P. Dole, and added that corroborating evidence was received from Indian Agent Samuel Colley. In September, Evans had instructed the military commanders to not allow Indians to loiter about the forts or purchase supplies. Now he ordered Colley to stop supplying them with guns. With the trouble in 1863 and the news of threatened warfare in the spring, the coming winter would be a time of apprehension. It was a hard season, and the Indians in Colorado Territory took shelter in the sparsely timbered bottoms, relatively snug beneath their lodge skins and buffalo robes, as were the settlers and miners in their lodges of wood or adobe.1

The white settlers found more to worry about in January 1864, when the Second Colorado Cavalry was ordered to the Missouri border to guard against Confederate bushwhackers. With only the First Colorado to defend the territory, Governor Evans and many citizens grew increasingly anxious about the approaching spring. Evans believed a massive attack on the scale of the Minnesota uprising would surely occur. He wanted more troops, but was told to utilize the militia if the need arose. This late in the war, though, few men were willing to join a militia unit. Evans was quickly becoming aware that Coloradans were generally not cut out to be soldiers. As the Rocky Mountain News lamented, that “About ninety-nine hundredths of the citizens of Denver who are able to bear arms are constitutionally opposed to doing so.”2

Governor Evans continued to forward his concerns to Maj. Gen. Samuel H. Curtis, in charge of the Department of Kansas, of which the Colorado Territory was now a part. Curtis had his own problems, and was also being bombarded with pleas from Kansas citizens for protection along the Fort Scott and Santa Fe roads. On March 18, he wrote to his boss, Maj. Gen. John Pope, “An immense emigration is concentrating in the Platte Valley en route for the Bannock mines, and they are liable to create trouble with the tribes northwest of Laramie, whose territory they will undoubtedly invade.” Most of all, there was a continuing need for troops to counter the bushwhackers and Rebels on the borders of Missouri, Arkansas, and Indian Territory. Colorado was of secondary concern. Curtis wrote back to Evans, “I am glad to have transmitted to my notice all intelligence of a credible nature Your Excellency can send me, and I will take due notice and govern myself accordingly.” Not only would Curtis not send more soldiers to Colorado, be he also informed Evans, “I am obliged to draw every man who can be spared from the Indian frontier to operate against rebels who have devastated this State of Kansas.”3

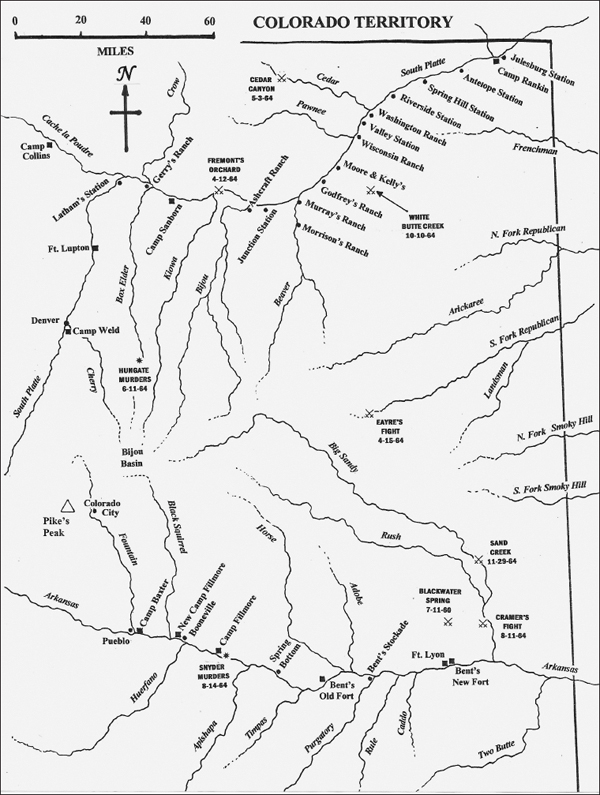

Evans would have to make do on his own. By April, some of his fears were realized. In Bijou Basin, a circular valley about 65 miles southeast of Denver, government freighters Irwin and Jackman fattened up their herd for the spring hauling, but Cheyenne Indians drove off 175 cattle. Herders trailed the stolen stock, following tracks leading eastward to Sand Creek. They eventually gave up and returned to Denver with the news of the thefts. General Curtis was notified and orders went back to Colonel Chivington as well as Lt. Col. William Collins at Fort Laramie: “Handle the scoundrels without gloves if it becomes necessary.” Chivington dispatched Lt. George S. Eayre after the culprits. Lieutenant Eayre, along with Capt. William McLain, who commanded an independent artillery battery, left on April 8 with 54 men of the battery, two 12-pounder mountain howitzers, and 26 men of the First Colorado. They picked up the trail, crossed the divide between the waters of the Platte and Arkansas, and moved down Sand Creek.4

While Eayre was searching, rancher W. D. Ripley rode into Camp Sanborn on the South Platte River to report that Cheyenne were stealing his stock along Bijou Creek. Lieutenant Clark Dunn and 40 men of Companies C and H of the First Colorado went with Ripley to recover the stock. On April 12, about three miles from Fremont’s Orchard, Dunn spotted about 15 Cheyenne driving horses across the South Platte. Ripley announced that the horses were his. Dunn and 15 troopers confronted the warriors while Ripley and four men went after the stock. The Cheyenne approached Dunn in an effort to shake hands to prove they were friendly. Dunn was wary, however, and made the mistake of trying to disarm them. Shooting began, the Indians bolted, and Dunn tried to catch them. Each side claimed the other fired first. The chase continued for nearly 15 miles before Dunn gave up. Four of his men were wounded—two of them fatally—and the Cheyenne took four casualties.5

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Eayre was trailing cattle into eastern Colorado. On April 15 at the headwaters of the South Fork Republican they found a fivelodge Cheyenne camp. The inhabitants were already fleeing, and a few warriors were riding their way. Soldiers tried to capture them, but the warriors shot and wounded one. When McLain unlimbered the battery, all the Indians fled. Eayre rode into the abandoned camp and burned it. The next day they found and burned another deserted camp and recovered 19 cattle said to belong to Irwin and Jackman. With the army mules breaking down from the strain of pulling their heavy wagons, Eayre returned to Denver. The Plains War of 1864 had begun.6

The Coloradans’ preemptive strikes may have only made things worse. Major Jacob Downing, of the First Colorado, rode out with Lieutenant Dunn and 60 men looking for more Indians. Downing’s column rode a circuitous route of 140 miles before returning to Camp Sanborn empty-handed. “Everything indicates the commencement of an Indian war,” he wrote in a letter to Chivington. “Active measures should at once be adopted to meet them on all sides, or the emigration will be interrupted. The people along the Platte are generally very much terrified.”7

Downing tried again. On May 1 near American Ranch on the South Platte, he captured a half-Lakota man named Spotted Horse. Under threat of death, they forced him to lead the soldiers to the nearest Indian camp. With 40 men of Companies C and H, Downing rode north to Cedar Canyon and, on May 3, found a 14-lodge camp. Downing moved to cut off the pony herd from the camp and his troops killed two young herders in the process. Ten men were detailed to guard the ponies while Downing divided his small command to move against the Indians. Most of them hurried for cover. While several warriors fired from behind some rocks, the women and children headed up the canyon. Downing had a tough time advancing against the warriors’ fire. He tried to draw them out, but they would not be baited. After a three-hour fight, one of his soldiers was killed and one was wounded. Downing had enough, and with “the carbine ammunition getting rather scarce, and the Indians so concealed that after fifty shots I could scarcely get a man, I concluded to return” to American Ranch. Downing took 100 captured horses with him. He claimed to have killed 25 Indians and wounded 35 more—which was probably more people than were in the entire village at that time. The Cheyenne acknowledged only two women and two boys killed. An excited Downing sent a note to Chivington immediately upon his return: “Send me more troops; I need them. The war has commenced in earnest.”8

Any war that had begun was mostly due to the efforts of the Colorado soldiers. General Curtis began to realized that matters were spiraling out of control and cautioned Governor Evans to tone it down. “I hope, therefore,” Curtis wrote, “Your Excellency will dispense with all the Federal troops you can spare, and use your utmost efforts, by kindness and militia force, to keep down Indian troubles and side issues that draw away men” Curtis would rather use with better effect in Kansas and Missouri. For the time being, Evans and Chivington were to cool their heels with the Plains tribes.9

Unfortunately, Lt. George Eayre was out once more hunting Indians. The lieutenant had returned to Denver for reinforcements. This time with lighter wagons, 84 men, and McLain’s battery, his column headed east to the Smoky Hill River in Kansas. Eayre effectively disappeared for almost two weeks, and his superiors wondered where in the world he had gone. It was May 16 when the command stumbled into about 250 Cheyenne lodges at Big Bushes, some 40 miles northwest of Fort Larned at the junction of Big Timber Creek and the Smoky Hill.

When a line of warriors appeared on a hill ahead, Eayre hurriedly tried to form his cavalry into line. Lean Bear, who had met with President Abraham Lincoln the previous year and was given a silver peace medal, was apprehensive, but nevertheless rode out to see what the soldiers wanted. He probably did not recall Uncle Abe’s words, “You know it is not always possible for any father to have his children do precisely as he wishes them to do.” Lean Bear and his companion, Star, rode downhill as other warriors began moving around the flanks. Private Asbury Bird watched the men approach. “When the two Indians came to meet us they appeared friendly, but when they saw the command coming on a lope they ran off. No effort was made by Lieutenant Ayres to hold a talk with the Indians.” In a flash, related Bird, “we were attacked by about seven hundred Indians.”

The Cheyenne Wolf Chief told a different story. According to him, Lean Bear told them to stay where they were so they would not frighten the soldiers and rode forward to shake their hands. “When the chief was only within twenty or thirty yards of the line,” he continued, “the officer called out in a very loud voice and the soldiers all opened fire on Lean Bear and the rest of us.” Lean Bear and Star were shot off their horses and the troops pumped round after round into them. They were so engrossed with the Indians in their front that they did not realize that hundreds of other warriors had gotten around their flanks. “They were so close that we shot several of them with arrows,” continued, Wolf Chief. “Two of them fell backwards off their horses…. More Cheyennes kept coming up in small parties, and the soldiers were bunching up and seemed badly frightened.”

As troops and warriors merged—Eayre estimated the Indians numbered from 400 to 500—the scene became a vortex of shouts, shots, and confusion. The howitzers, loaded with small pieces of lead, rumbled up and were unlimbered on level prairie, but the artillerymen could not elevate their pieces high enough to hit the warriors on the hillsides. “The grapeshot struck the ground around us,” said Wolf Chief, “but the aim was bad.”

Soon, Black Kettle arrived and frantically rode among the warriors calling, “Stop the fighting! Do not make war!” “But,” said Wolf Chief, “it was a long time before the warriors would listen to him. We were very mad.” Black Kettle may have prevented serious losses on both sides. He reined in many warriors and a lull ensued. Eayre saw the opportunity to strengthen his position. When the wagons came up, he organized his men and the howitzers inside a makeshift square of dismounted cavalry. The most persistent attacks were over, but a moving fight continued for seven hours and about seven miles before the last of the warriors gave up the chase. The Cheyenne lost three killed and several wounded, while Eayre claimed he had killed three chiefs and 25 warriors. Eayre lost four killed and three wounded, and 15 saddled cavalry horses were captured. Eayre headed south toward Fort Larned, where he arrived on May 19. The war was about to be kicked into high gear.10

Lieutenant Eayre had his fill of Indian hunting, but the Cheyenne, who had engaged in some sporadic raiding up to this point, were now infuriated. Heavy raiding immediately began along the Santa Fe Trail, as was usual almost every year when the grass grew green for the ponies and the weather warmed. The routine spring raiding began concurrently with Eayre’s encounter.

Charles Rath owned the Walnut Creek Ranch 20 miles northeast of Fort Larned and 40 miles east of the Big Bushes fight. The day of the that fight, Cheyenne rode to Rath’s ranch and stole his Cheyenne wife, telling him they were going “to kill all the whites they could find.” Rath gathered all the goods he could pile into his wagons and sent them east with a few of his men. He and two employees, meanwhile, built a defensive position on the roof of the ranch house. The next morning the Cheyenne returned, stole horses and mules, and carried off whatever remaining goods they could find. The three white men decided to let well enough alone and escaped with their lives after the raiders left.

Other Indians hit Curtis’ and Cole’s Ranch at the Great Bend of the Arkansas, and the Cow Creek Ranch about 15 miles northeast of Rath’s. Indians also hit settlers and merchants along the roads east to Salina. By May 18, citizens had sworn out affidavits that depredations were being committed between Fort Larned and Fort Riley. Settlers fled their homes in the Smoky Hill country and congregated as far east as Abilene. One civilian deposition concluded, “The terror among the frontier settlements is general, and unless aid is afforded the probability is that all the settlements will be abandoned, if the settlers are not murdered.”11

Many Indians were involved in the May raids, but only a minority could blame their marauding on retaliation for Eayre’s killing of Lean Bear. Eayre, however, added fuel to the fire that was already smoldering. As such, he became a convenient patsy as the man who started an Indian war—until a bigger culprit in the person of John Chivington stepped in six months down the road.

At this time, Curtis wanted all available troops moved east to deal with the larger Confederate threat, while Chivington and Governor Evans shuffled their meager forces to deal with what they believed was a full-scale Indian uprising. Chivington was certain bloodshed was the only answer. “The Cheyenne will have to be soundly whipped before they will be quiet,” he cautioned Maj. Edward W. Wynkoop, who was in command at Fort Lyon, on the last day of May. “If any of them are caught in your vicinity kill them, as that is the only way.” On May 28 Evans wrote to General Curtis explaining his predicament. Colorado troops had been sent out of the territory, and “Now we have but half the troops we then had, and are at war with a powerful combination of Indian tribes, who are pledged to sustain each other and drive the white people from this country.” Evans believed his prediction had come true. “The depredations have commenced precisely as foretold in my communications to the Departments last fall.”12

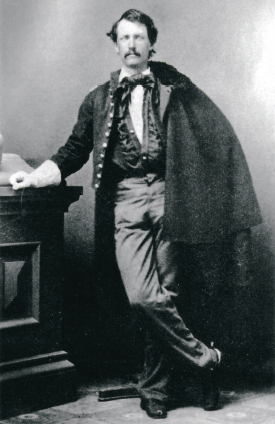

Major Edward W. Wynkoop, First Colorado

He tried to bring peace, but his actions led to the Sand Creek incident.

The Denver Public Library

It was something of a self-fulfilling prophesy. The Coloradans were so certain the Indians would go to war that when the inevitable (and not uncommon) stock thefts occurred, it was seen as something different: The beginning of a great uprising. White retaliation resulted in Indian reprisals, and a snowball became an avalanche. In early June, when Indian raiders drove off 150 cattle and horses along the South Platte, the telegraph operator at Junction Station tapped off the sarcastic question, “Where is Chivington and his bloodthirsty tigers?”13

The Denverites were already on edge when the latest news arrived from Running Creek. On June 11, a band of perhaps a dozen Arapaho were in the area stealing horses from ranches and freighters and paid a visit to Isaac Van Wormer’s place 35 miles southeast of Denver, a ranch being operated by Van Wormer’s hired man Nathan Hungate. Perhaps the Indians believed the ranch would be easy pickings, but Nathan had other ideas. The raiders were running off some stock when a hail of gunfire rang out from the ranch house. One or more Indians may have been hit, and the Arapaho decided to teach the defiant hired hand a lesson. Bullets blasted the ranch house while Hungate’s two little daughters cowered in a corner and his wife Ellen bravely loaded several available weapons. Ellen may also have been firing, for the pair put up quite a defense. Frustrated, the Arapaho set the house on fire, and the Hungates had no choice but to flee the burning structure. Ellen and the children were cut down within a few hundred yards. The angry warriors vented their rage upon them, raping Mrs. Hungate before stabbing and scalping her. The two young girls, one an infant of three or four months and the other two years old, had their heads nearly severed, and the infant was disemboweled. Nathan made it another mile, working his Henry rifle before succumbing to wounds. The Indians desecrated his corpse and disappeared east onto the plains.14

On June 15, the Hungates’ bodies were carried into Denver and displayed in a wagon box. The Commonwealth, a Denver newspaper, printed a clarion call cal arms:

A HORRIBLE SIGHT! The bodies of those four people who were massacred by the Cheyennes on Van Wormer’s ranch, thirty miles down the Cut-off, were brought to town this morning, and a coroner’s inquest held over them. It was a most solemn sight indeed, to see the mutilated corpses stretched in the stiffness of death, upon that wagon bed, first the father, Nathan Hungate, about 30 years of age, with his head scalped and his cheeks and eyes chopped in as with an axe or tomahawk. Next lay his wife, Ellen, with her head also scalped through from ear to ear. Alongside of her lie two small children, one at her right arm and one at her left, with their throats severed completely, so that their handsome little heads and pale innocent countenances had to be stuck on, as it were, to preserve the humanity of form. Those that perpetuate such unnatural, brutal butchery as this ought to be hunted to the farthest bounds of these broad plains and burned to the stake alive, was the general remark of the hundreds of spectators this afternoon.15

The slaughter put Denver into an uproar. Mobs broke into the ordnance stores demanding guns and ammunition. On the night of the 19th, a panic swept through town when horsemen came tearing down the streets, Paul Revere-like, shouting that the Indians were coming. At Camp Weld, Mollie Sanford rushed for her door at the furious pounding and opened it to see a soldier with “his eyes almost starting from their sockets.”

“Run, wimmen!” he cried. “Run for your lives, the Injuns are coming three thousand strong! Run for the brick building at Denver! Governor’s orders! But don’t get skeered.”

“I was already about paralyzed,” Mollie admitted, but another woman who shared the quarters with her “immediately went into hysterics.”

Mollie spread the word around the barracks and soon all the women were shrieking. She wanted to flee but decided to wait for her husband, Lt. Byron H. Sanford. When he arrived, they gathered their two children and some essentials and walked to town. By daylight the streets were filled with families, but there were no traces of Indians and the scare petered out. Mollie later learned that it had all begun when some folks living outside town saw some Mexican cattle drivers and thought they were Indians. The Denver Commonwealth elaborated:

The great panic of last night will never be forgotten by anyone who witnessed or shared it. It was terrible as causeless, and as unreasonable…. There are dangers, but none which preparation will not avert. It may require some sacrifice of time and comfort, but in mercy to poor women, don’t let us make them suffer another such a fright.16

Exaggerated as it may have been, the Indian menace was real enough to the Coloradans, and rumor believed is reality. Governor Evans began organizing the militia and wrote the War Department for permission to raise another regiment of volunteers. On June 27, Evans decided to wait no more and issued an ultimatum addressed “To the Friendly Indians of the Plains”:

Agents, interpreters, and traders will inform the friendly Indians of the plains that some members of their tribes have gone to war with the white people. They steal stock and run it off, hoping to escape detection and punishment. In some instances they have attacked and killed soldiers and murdered peaceable citizens. For this the Great Father is angry, and will certainly hunt them out and punish them, but he does not want to injure those who remain friendly to the whites. He desires to protect and take care of them. For this purpose I direct that all friendly Indians keep away from those who are at war, and go to places of safety…. The object of this is to prevent friendly Indians from being killed through mistake. None but those who intend to be friendly with the whites must come to these places. The families of those who have gone to war with the whites must be kept away from among the friendly Indians. The war on hostile Indians will be continued until they are all effectually subdued.

Evans and almost every citizen of Colorado Territory were sure there was a war on. There was no doubt the soldiers were on a war footing. The Cheyenne and Arapaho were certainly aware of the war, and even the Lakota, when in council with the US Army at Fort Cottonwood in June, remarked that they would try to keep their people out of the way “until this war is over between the whites and Cheyennes.”17

The Army command, however, appeared to be in denial about the matter. General Curtis ordered Chivington to move his troops to central Kansas. He believed “a good company or two, with two howitzers well attended, is no doubt sufficient to pursue and destroy any band of Indians likely to congregate anywhere on the plains, and it is bad economy to divert needless numbers in pursuit of Indians.”

On July 5, having grown tired of Evans’s constant cry for help, Curtis finally snapped:

I may not have all you have seen and heard, but I am sure I have great deal on the subject which you have not seen nor heard, and I am obliged to Your Excellency for all the intelligence which you have sent me…. While prepared for the worst as far as possible we may not exhaust our efforts in pursuit of rumors, and I, therefore, request you to send me telegraphic information of outrages which were fully ascertained.18

After Evans issued his ultimatum, he told Agent Sam Colley to employ John Smith, his son Jack, and William Bent to spread the word to get the peaceful Indians together because the non-complying Indians would be treated as hostile and bent on mischief. While some heeded the warning, others were out raiding. In mid-July, Satanta and his Kiowa attacked Fort Larned and stole about 170 horses. Kiowa, Comanche, and Arapaho raiders attacked wagon trains in the Great Bend area, killing 10 teamsters and plundering the wagons. The friendly Arapaho Left Hand rode to Fort Larned to talk, but the nervous soldiers shot at him, which only further served to anger many young warriors. Cheyenne and Arapaho raided ranches along the South Platte in Colorado.

In August, Indians attacked a wagon train at Lower Cimarron Springs in Kansas, killing five men. There was fighting across the Central Plains and down into Texas. With so many Indians in non-compliance with Evans’s ultimatum, Agent Colley weighed his possibilities. With a war on, he could probably hold back the annuity goods—food and other supplies the US government provided to the Indians in exchange for land—he had been stockpiling, even though Maj. Scott Anthony at Fort Lyon had already forced him to distribute much of it. When he learned of the increasing depredations, the Indians’s “good friend” Sam wrote to Governor Evans, “I now think a little powder and lead is the best food for them.”19

There was plenty of fighting prior to August 1864, but early that month the conflict increased another notch. Along a 60-mile stretch of the Little Blue River in Nebraska between August 7-9, hundreds of Cheyenne and Lakota warriors devastated the ranches and roads. When the assault was over, 38 settlers were dead, nine were wounded, and five were captured. On August 8 farther west along Plum Creek near the Platte River, Cheyenne attacked wagon trains and stagecoach stations, leaving 13 people dead and capturing two more.20

Like Governor Evans, Governor Alvin Saunders of Nebraska and Governor Thomas Carney of Kansas cast about for help. General Robert B. Mitchell reacted, writing to General Curtis, “I find the Indians at war with us through the entire District of Nebraska from South Pass to the Blue, a distance of 800 miles and more, and have laid waste the country, driven off stock, and murdered men, women, and children in large numbers. In my humble opinion,” he continued, “the only way to put a stop to this state of things will be to organize a sufficient force to pursue them to the villages and exterminate the leading tribes engaged in this terrible slaughter.”21

A frustrated Governor Evans nullified his June proclamation to the friendly Indians, and on August 11 issued a new one in the Rocky Mountain News:

All citizens of Colorado, either individually or in such parties as they may organize, to go in pursuit of all hostile Indians on the plains, scrupulously avoiding those who have responded to my said call to rendezvous at the points indicated, also to kill and destroy as enemies of the country wherever they may be found, all such hostile Indians. And further, as the only reward I am authorized to offer for such services, I hereby empower such citizens, or parties of citizens, to take captive, and hold to their own private use and benefits, all property of said hostile Indians that they may capture.22

Evans had just given carte blanche to raid and kill Indians, and unfortunately, few Indians subscribed to the newspaper. “All good citizens,” concluded the proclamation, “are called upon to do their duty for the defense of their homes and families.” Coincidentally, that same day the War Department in Washington authorized Evans to raise a 100-days regiment of cavalry or infantry at his discretion. The papers trumpeted the news. To many, it finally appeared as though Colorado had been given the means for its salvation.23

With Evans issuing a proclamation that sanctioned open season on the Indians, there was no telling what would happen. On August 11 near Sand Creek, Lt. Joseph Cramer of the First Colorado led 15 troopers in a chase against Neva and a small band of Arapaho on their way to Fort Lyon to talk peace. Neva carried a copy of Evans’s initial armistice proposal, but Cramer’s aggression drove him off in a running skirmish.

From that time on, it would not be easy for Indians to demonstrate their goodwill. At Fort Lyon, Major Wynkoop wrote to Chivington that two of his men had been recently murdered. He also complained that his carbines were “absolutely worthless,” but he intended to present a bold front. “At all events,” he added, “it is my intention to kill all Indians I may come across until I receive orders to the contrary from headquarters.”

Sam Colley also painted a pessimistic picture in a letter to Governor Evans. “The Indians are very troublesome,” he complained, writing of the Cramer affair. He believed large war parties were nearby. Contractors were working on a new agency at Point of Rocks, but Colley feared it “will have to be abandoned if troops cannot be obtained to protect it. I have made application to Major Wynkoop for troops. He will do all he can, but the fact is we have no troops to spare from here…. I fear that all the tribes are engaged.” The Arapaho he had been feeding, added Colley, “have not been in for some time. It looks at present as though we shall have to fight them all.”24

On August 14, Arapaho under Little Raven’s son had just stolen stock from Point of Rocks Agency when they came across a wagon making its way to Fort Lyon from Denver. The Indians attacked and killed three men, including John Snyder, a soldier stationed at the fort who had been allowed to ride in the wagon to Denver to pick up his wife. Anna Snyder was captured in the attack and taken to a camp on the upper Solomon in Kansas. Only a short time after she arrived there she tried to escape, but was recaptured. The distraught woman had watched her husband slaughtered and despaired of ever being released. One night she tore up her calico dress into strips, twisted them into a rope and hanged herself from the crossed tipi poles in a lodge. Some thought the Arapaho had killed her.25

War parties were still out. In north-central Kansas in early August, four homesteaders—John and Thomas Moffitt, John Houston, and James Tyler—picked a bad time to go on a buffalo hunt and died for their efforts. On August 21, Cheyenne under Little Robe attacked a large number of freight wagons camped at Cimarron Crossing of the Arkansas River, killing 11 men and driving off about 130 mules.26

The various tribal camps spread across the Central Plains were becoming loaded with contraband goods, stolen horses, mules, and captive white women and children, but the raiding season would come to an end. Winter was a time to take shelter in isolated creek bottoms and wait out the weather in comparative safety and comfort. Peace negotiations were essential. In Black Kettle’s Cheyenne camp, George Bent, the mixed-blood son of the white trader William Bent, and Edmund Guerrier, another mixed-blood married to George’s sister Julia, wrote two (nearly) identical letters—one to Agent Colley and the other to the commanding officer at Fort Lyon. Here was what the wrote:

Cheyenne Village, August 29, 1864

Sir:

We received a letter from Bent, wishing us to make peace. We held a council in regard to it; all came to the conclusion to make peace with you, providing you make peace with the Kiowas, Comanches, Arapahoes, Apaches and Sioux. We are going to send a message to the Kiowas and to the other nations about our going to make peace with you. We heard that you have some prisoners at Denver; we have seven prisoners of yours which we are willing to give up, providing you give up yours. There are three war parties out yet, and two of the Arapahoes; they have been out some time and expected in soon. When we held this council there were few Arapahoes and Sioux present. We want true news from you in return, that is a letter.

Black Kettle and other Chiefs27

Some of the tribes were suing for peace, but the Coloradans still had nightmares of being tomahawked in their sleep. They may have gotten some relief knowing that a new regiment was being organized, but it seemed as if they had been calling for help forever and most of their warnings had been ignored as trivial complaints. Some historians have disregarded their pleas as no more than crying “wolf,” or as a plot by Evans and William N. Byers, editor of the Rocky Mountain News, to stir up a war for their own political ends.28 Although the terror may have been unfounded, a century and more later it is easy to overlook the very real fears felt by the isolated white population.

Initially, volunteers responded well to Governor Evans’s call for troops. Sixty men from the mining camp of Central City signed up in one afternoon after a recruiting promotion made by mining engineer Hal Sayr and future senator Henry M. Teller. In a few days, 44 more men had joined and marched to Denver to be mustered in as Company B, Third Colorado. In similar fashion, four companies were raised in Denver and one in Boulder. In the Rocky Mountain News of August 24, a line read, “Over seven hundred men are enlisted for the new regiment. Pretty good recruiting for a single week.” The initial recruiting may have gone well, but most Coloradans were not convinced that their survival depended on flocking to the colors. On August 18, Colonel Chivington proclaimed martial law, closed down businesses, and made additional efforts to get more men. Enough joined in the counties of Pueblo and El Paso to form Company G. There was little gear for them and many waited for almost two months before they received adequate arms, equipment, and horses.

Despite the relatively successful recruitment effort, most Coloradans were not enthusiastic Indian fighters. They had moved there to begin a new life, get rich, or escape the Civil War. The territories were havens for draft dodgers. General Curtis had expressed his concern. Every time there was a gold discovery, it impacted the dwindling population’s available to fight. “It is hard to tell whether love of gold or fear of the draft has the longest end of the singletree,” Curtis wrote. It took another month to raise the remaining companies.

Ultimately, a total of 1,149 men enrolled. Of the approximately 800 men whose occupations were known, more than 500 were farmers and miners, and about 200 were laborers, clerks, teamsters, carpenters, engineers, printers, and merchants. The men were not the dregs of society as some have claimed, but a typical cross-section of citizens. And most of them, some enthusiastically and others reluctantly, were ready to fight Indians if they could get weapons and find a target before peace or winter prevented it.29

The Third Colorado began assembling in late August at Camp Evans, a post on the South Platte a few miles north of Denver. Because of logistics and supply problems, however, the entire regiment never did gather in one place. There were simply not enough supplies and mounts for them. From the start, only about 375 horses were available to mount the new regiment. Captain Cyrus L. Gorton, assistant quartermaster, scrambled to purchase 120 more horses on the open market, which, he said, “was entirely irregular” for he had no authority to buy them. Eventually they got about 725 horses, which still left some 300 soldiers without mounts. They only got enough horses to mount the entire regiment in December—when the enlistments expired. The regiment was issued two howitzers, 1,103 used rifles and muskets (mostly old .54 calibers), and 103 used pistols. Colonel George L. Shoup assumed command on September 21.30

The Third Colorado was as ready for action as it would ever be.

1 Evans to Dole, November 10, 1863, OR 34, pt. 4, 100; Harry E. Kelsey, Jr., Frontier Capitalist: The Life of John Evans (Denver, CO, 1969), 135.

2 Roberts, “Sand Creek,” 201-02.

3 Curtis to Pope, March 18, 1864, Curtis to Evans, March 26, 1864, OR 34, pt. 2, 652, 742-43.

4 Eayre to Chivington, April 23, 1864, OR 34, pt. 1, 881; Mitchell to Commanding officer, Fort Laramie, April 7, 1864, OR 34, pt. 3, 85.

5 Gregory F. Michno, Encyclopedia of Indian Wars Western Battles and Skirmishes, 1850-1890 (Missoula, MT, 2003), 134-35.

6 General Curtis at Fort Leavenworth was also getting edgy. On April 19, he wired Brig. Gen. Benjamin Alvord, commanding the District of Oregon, in an effort to coordinate their efforts. Curtis wrote that a “vast army of immigrants” was converging on the Platte Valley and he was not sure he could protect them. Ibid.

7 Downing to Chivington, April 20, 1864, OR 34, pt. 3, 233, 242, 250-52.

8 Downing to Chivington, May 3, 1864, OR 34, pt. 1, 907-08; Doris Monahan, Destination: Denver City The South Platte Trail (Athens, OH, 1985), 142-43. American Ranch was also known as “Moore & Kelley’s.”

9 Curtis to Evans, May 9, 1864, OR 34, pt. 3, 531.

10 Wynkoop to Maynard, May 27, 1864, OR 34, pt. 1, 934-35; Wynkoop to Maynard, June 3, 1864, Alfred Gay to G. O’Brien, June 10, 1864, OR 34, pt. 4, 208, 403, 460-62; U.S. Congress, Senate. “The Chivington Massacre,” Report of the Joint Special Committee on the Condition of the Indian Tribes, Senate Report 156, 39th Congress, 2nd Session (Washington, DC, 1867), 72, 75; Savoie Lottinville, ed., Life of George Bent Written From His Letters (Norman, OK, 1968), 131-32; Peter John Powell, People of the Sacred Mountain, Vol. I (San Francisco, CA, 1981), 263-64.

11 Donald J. Berthrong, The Southern Cheyennes (Norman, OK, 1963), 188; Louise Barry, “The Ranch at Walnut Creek Crossing,” Kansas Historical Quarterly (Summer 1971), 37, no. 2, 143-44; Louise Barry, “The Ranch at Great Bend,” Kansas Historical Quarterly (Spring 1973), 39, no. 1, 96-98; OR 34, pt. 3, 661.

12 Evans to Curtis, May 28, 1864, OR 34, pt. 4, 98, 151.

13 Monahan, Denver City, 151.

14 Jeff Broome, “Indian Massacres in Elbert County, Colorado New Information on the 1864 Hungate and 1868 Dietemann Murders,” The Denver Westerners Roundup (January-February 2004), 11-15.

15 Scott C. Williams, ed., Colorado History Through the News (a context of the times.) The Indian Wars of 1864 Through the Sand Creek Massacre (Aurora, CO, 1997), 44. The effect of the Hungate killings on Denver was powerful and long-lasting. Stephen Decatur, who later fought at Sand Creek, testified that he had counted with real satisfaction the number of dead Indians after that event. “I was at the house of Mrs. Hungate only a few days before she was murdered, and I became attached to her and her babes, and I wished her friends to know how many of the bloody villains we had killed,” explained Decatur. U.S. Congress, Senate. “Sand Creek Massacre,” Report of the Secretary of War, Senate Exec. Doc. 26. 39th Congress, 2nd Session (Washington, DC, 1867), 198.

16 Mollie D. Sanford, Mollie: The Journal of Mollie Dorsey Sanford in Nebraska and Colorado Territories 1857-1866 (Lincoln, NE, 1976), 187-88; Williams, Through the News, 59.

17 Kelsey, Frontier Capitalist, 143; Washington Henman, June 8, 1864, OR 34, pt. 4, 459.

18 Curtis to Chivington, June 29, 1864, OR 34, pt. 4, 595; Curtis to Evans July 5, 1864, OR 41, pt. 2, 53.

19 Kelsey, Frontier Capitalist, 144.

20 Michno, Encyclopedia of Indian Wars, 147-49.

21 Mitchell to Curtis, August 15, 1864, OR 41, pt. 2, 722. Many orders were issued to exterminate Indians. General James H. Carleton gave orders to Kit Carson to kill all male Indians. Colonel Patrick Connor gave orders to his troops to kill all the males. General George Crook issued orders to hunt down and kill all Apaches. Generals Pope, Mitchell, Blunt, Curtis, Sherman, and Sheridan used phrases that contained the words “kill” or “extermination,” but genocide was never formal policy. William Dole, in Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs 1862, 188, expressed the official viewpoint: “The idea of exterminating all these Indians is at once so revolting and barbarous that it cannot for a moment be entertained.” Yet, perhaps we are walking the line between de jure and de facto policy.

22 Williams, Through the News, 118-19, 124-27.

23 Williams, Through the News, 118-19, 124-27.

24 Wynkoop to Maynard, August 13, 1864, OR 41, pt. 1, 237-40; Colley to Evans, August 12, 1864, OR 41, pt. 2, 673.

25 Gregory F. Michno, Battle at Sand Creek The Military Perspective (El Segundo, CA, 2004), 138-39.

26 Gregory F. Michno and Susan J. Michno, Forgotten Fights Little-Known Raids and Skirmishes on the Frontier, 1823 to 1890 (Missoula, MT, 2008), 205-07.

27 Report of the Secretary of War, 1867, Exec. Doc. 26, 39th Congress, 2nd Session, xi, 169, hereafter referred to as “Sand Creek Massacre.” This letter has been reprinted with various spellings.

28 Margaret Coel, Chief Left Hand: Southern Arapaho (Norman, OK, 1981), 181, 186-92, 197; Berthrong, Southern Cheyennes, 169, 171; Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (New York, NY, 1970), 74-75; David H. Bain, Empire Express Building the First Transcontinental Railroad (New York, NY, 1999), 185-88.

29 Michno, Battle at Sand Creek, 144-46.

30 “Sand Creek Massacre,” 160-62, 175.