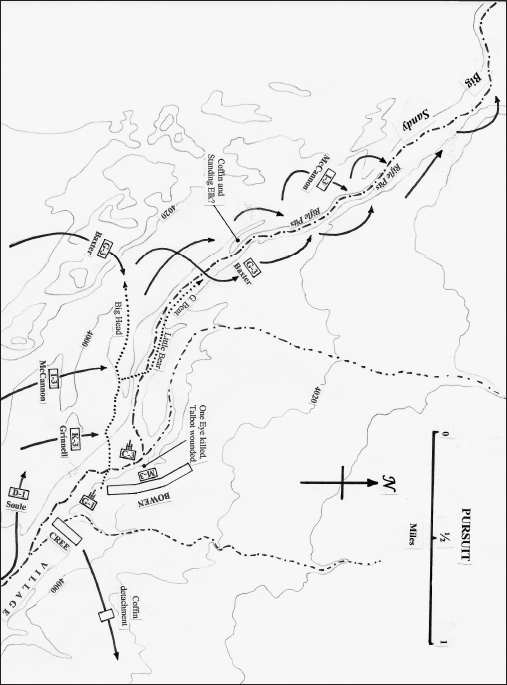

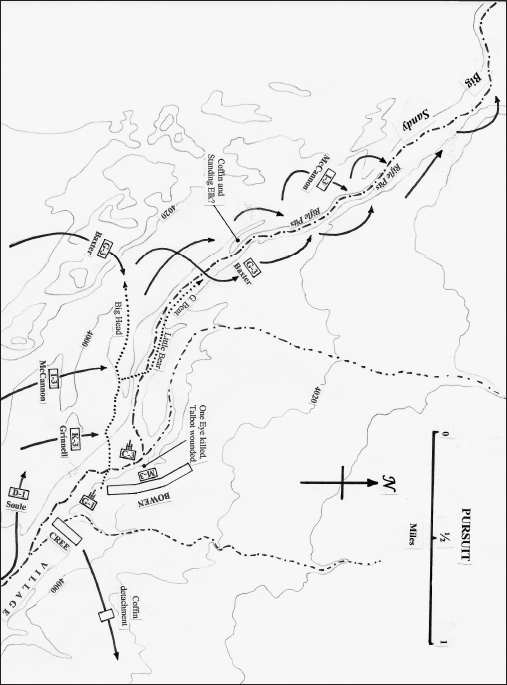

The Colorado volunteers moved through the village on a southeast to northwest axis. Only a few Indian dead were found at the northwest end of the main village, and only a few soldiers had been killed. So far, the fighting had been light.

Thaddeus P. Bell of Company M, Third Colorado, was passing among the tipis when he peeked into an Indian lodge. Lying on the ground was the fresh scalp of a red-haired man.1 In the abandoned camp, Chivington changed his troop formation from line to column, which he would not have done in the face of a resisting enemy, and continued up the left and right banks of the creek.

Company G of the First Colorado unlimbered its guns near the creek on the south side, while Company C of the Third Colorado unlimbered nearby on the north side. Company G had been left behind in the run toward the village, said Cpl. James J. Adams, because the mules drawing the artillery gave out. They caught up after the cavalrymen were already firing and, according to Sgt. Lucien Palmer, the Indians had already moved up the creek several hundred yards. “We threw several shells, which did not reach them,” he testified. Hauling the pieces all the way out to Sand Creek seemed to be a wasted effort, for the men only carried with them 16 rounds of ammunition per gun.

Up ahead of them, Morse Coffin saw an artillery shell burst about 100 feet above some Indians who had taken refuge along the banks. Baldwin’s battery fired several times before moving upstream to a new position. After unlimbering again, related Palmer, “We threw several rounds of grape and canister at them when they were entrenching themselves on the opposite side of the creek.” The artillery ammunition was quickly exhausted.2

The main command, meanwhile, approached the village from the southeast. But when Irving Howbert’s company secured the ponies, they approached out of the south, which allowed the Indians to retreat to the west and north. Those were not the only avenues of escape. Some also slipped away to the south, in the same direction from which the soldiers had just come.

Jim DuBois was still walking north after his horse played out. At daybreak, alone on the open plains, he heard the sound of guns and forced his tired legs to keep moving. After another hour, and now within two or three miles of the battlefield, he spotted a large party of Indians about one mile to the west, heading south. As they drew near, he took cover and counted 75 Indians and nine horses. When DuBois reached the village, he told his story to Morse Coffin; both concurred this was the largest party of Indians to escape in one body.

By the time Howbert approached the field the action was rather heavy. “[T]he firing had become general,” he remembered, “and it made some of us—myself among the number—feel pretty queer. I am sure, speaking for myself, if I hadn’t been too proud, I should have stayed out of the fight altogether.”

To the north, Indians were riding away on ponies taken from another herd grazing on the far side of the village. Down in the creek bed, however, the fight was a hot one. “The Indian warriors concentrated along Sand Creek,” testified Howbert, “using the high banks on either side as a means of defense. At this point Sand Creek is about 200 yards wide, the banks on each side being almost perpendicular and from six to twelve feet high.”

The sight of the Indians running from the village was more than most of the volunteers could handle. They had kept in some semblance of order until then, but now the Indians were getting away, and the officers could no longer restrain the soldiers. According to Privates Shaw and Patterson, the left wing of the command broke after the Indians first. Colonel Shoup tried to check them, but as he did so the soldiers on the right side picked up the chase. “The officers lost control over them,” testified the privates, “for the volunteers, at sight of the Indians, remembered the crimes committed by their hands and were determined to wreak vengeance.” Private Chubbuck took note of the loss of discipline. “Colonel Shoup tried to keep the soldiers in line,” he said, “but he could not control them. They broke ranks and began firing as fast as possible. Some of them fought the Indians in the pits, some chased Indians out on the plains, and some chased Indians up the creek.”

Morse Coffin of Company D, Third Colorado, took in the chaotic scene unfolding along the creek bed: “From nearly opposite the village, and extending up the creek in a northwest direction, for, say, a half mile or more, the bed of the creek was dotted more or less thickly with moving humanity. I think a majority of these were women and children, and who seemed to be going away in a sort of listless, or dazed, or abandoned manner, as though they knew not what to do, nor where to go.” The village was deserted, but the Indians were waiting for the soldiers one-half mile upstream where the creek changed course abruptly from east to south.3

Captain Theodore G. Cree led a battalion consisting of Companies D, E, and F of the Third Colorado. They formed to the southeast of the village, moved forward along the north bank about one-half mile, and dismounted. The bank where Sergeant Coffin dismounted was four to six feet high, and the Indians made good use of the bluffs for defense. Some of the volunteers rushed to the creek bank without orders, and Coffin thought them foolhardy. An arrow hit Jim Arbuthnot’s horse. Hiram J. “Hi” Lockhart of Company D was thrown from his mount. As he tried to follow on foot, an Indian rose from the bank and shot at him. Lockhart went to ground and returned fire, but also missed. The Indian shot again before Lockhart could reload. The soldier dropped flat, for it was difficult to reload his old infantry musket while lying down. Finally, some of his company came up and killed the Indian that had him pinned down.

Coffin watched as many women and children took shelter in the creek bed. “I am of the opinion that no special attack was made on these women and others,” he later testified, “from the fact that comparatively few were found in that locality after the battle.” But when the artillery opened up, continued the Company D sergeant, they scattered up the creek and to the west bank, which was ten to fifteen feet high about a mile upstream.4

Lieutenant Colonel Bowen took his battalion of Companies A, H, L, and M of the Third Colorado through the deserted village and along the north side of the creek. Company M, under Capt. Presley Talbot, was in the advance. Its members emerged from the camp to find another cluster of tipis near the creek, defended by more Indians than they had faced before. Colonel Shoup described this as “the main body.” Most of the adult warriors of these families were said to be out hunting. A Cheyenne girl named Man Stand said that all who were left to protect them were teenage boys, but if so, they bravely took on the job. The oldest ones, armed only with bows and arrows, rode their ponies straight into Talbot’s oncoming soldiers. When they were scattered or killed, the younger boys went in, with the same result. Whether adult warriors or teenagers, they put up a good fight.

Irving Howbert described this part of the action: “I saw a line of about one hundred Indians receive a charge from one of our companies as steadily as veterans, and their shooting was so effective that our men were forced to fall back.” The troopers counter-charged and forced the Indians behind the banks of the creek, which they effectively used as breastworks. They retired in a “leisurely manner,” said Howbert, but they left “a large number of their dead on the field.” The remaining men and boys fled. One boy rode by Man Stand, grabbed her by the hair, and hoisted her on his pony. They rode away and survived.

John Smith, traveling with Lieutenant Baldwin’s battery, was near that spot where “about a hundred” Indians were cornered. The soldiers nearly destroyed them, although, Smith added, “Four or five soldiers had been killed, some with arrows and some with bullets.” The companies were scattered. “There were not over two hundred troops in the main fight, engaged in killing this body of Indians under the bank,” concluded Smith.

Jim Beckwourth claimed the Indians did not fight in the village and didn’t form up in a line of battle “until they had been run out of their village.” Once out in the open, they formed up and fought “until the shells were thrown among them,” at which time they broke and “fought all over the country.”

Major Anthony figured there were between 75 and 100 male warriors firing at them. He briefly described the confrontation: “Quite a party of Indians took position under the bank, in the bed of the creek, and returned fire upon us. We fought them about seven hours, I should think, there being firing on both sides.”

Many defenders lined the creek on the east side. “My company was permitted to charge the banks and ditches,” Captain Talbot recalled. “There I received so very galling a fire from the Indians under the bank and from ditches dug out just above the bank that I ordered my company to advance, to prepare to dismount and fight on foot.” As they moved in, the Indians fired a volley. Talbot’s orderly, Sgt. Louis P. Orleans, moved too near the bank and was hit with an arrow in the arm and a bullet in the side. He staggered and fell. Talbot spurred his horse toward Orleans to assist him, and as he did so, thought he recognized one of the warriors firing from only 75 feet away. “At the command to fight on foot I was shot,” he said, “with a ball about fifty to the pound, from the rifle of a chief known by the name of One Eye.” The projectile went through his groin on the right side. He dragged his right leg over his horse and tried to ease off, but fell to the ground. If the Indian was One Eye, he assuredly felt both anger and satisfaction when his ball plunked into a blue-clad officer.

With Talbot and Orleans down in front of the command, some warriors rushed forward but were met by soldiers determined not to let the wounded men be captured alive. “Indians,” said Talbot, “twenty-five or thirty in number, (bucks) made [a] charge, [and] were repulsed, some of my men clubbing their guns on account of [the] guns refusing to discharge, and forced [the] Indians to seek shelter under the banks, and in holes dug out for concealment.”

Theodore Chubbuck saw his captain go down along with two or three other volunteers who tried to go to his assistance. After the wild melee, a fiveminute lull in the fighting allowed Chubbuck and another soldier to rush forward. While his companion placed a blanket under Talbot’s right leg to ease his pain, the captain asked Chubbuck to fetch the doctor, who was thought to be riding with Capt. John McCannon’s Company I. Chubbuck hunched over and hurried back to his horse. Talbot spotted an Indian he recognized as Big Head stand up and wave a buffalo robe as if to draw their fire. When scattered shots rang out, the prone and wounded captain cautioned his men “to be guarded, hold their fire, and be very particular what they fired at, and to be sure it was an Indian.” While Talbot was being carried away, “The Indians,” he recalled, “en masse, at least thirty in number, made a charge, which was repulsed by eight of Company M” and two men of the First Colorado. The Indians, Talbot added, “acted with desperation and bravery.” He estimated that 30 Indians were killed within 75 feet of where his company fought. Big Head got away to head west across the prairie, only to run into McCannon and Baxter.

Colonel Shoup reported the same action. “Here a terrible hand-to-hand encounter ensued between the Indians and Captain Talbot’s men and others who had rushed forward to their aid, the Indians trying to secure the scalp of Captain Talbot,” testified Shoup. “I think the hardest fighting of the day occurred at this point, some of our men fighting with clubbed muskets, the First and Third Colorado Regiments fighting side by side, each trying to excel in bravery and each ambitious to kill at least one Indian.”

Privates Shaw and Patterson remembered the Indians being scattered over hundreds of acres, but there in the sand pits “was the principal scene of the fight. Some fought from ambush, some stood in the open and exchanged shot for shot; some struggled in hand-to-hand fights, using knives for weapons; squaws would take their bow and arrows and at every opportunity would down a soldier. No discipline was used; the soldiers had to fight in the savage fashion.”

Lieutenant Cramer, who was opposed to the fighting and often expressed it as a massacre, said the “warriors, about one hundred in number, fought desperately.” Billy Breakenridge believed that the Indians “were much better armed than the soldiers and they put up a desperate fight…. Although they put up a stubborn resistance and contested every inch of the ground, they were slowly driven back from one position to another for about four miles.”5

When the Coloradans broke through this defensive position, a slight lull ensued, as if both sides stopped to catch their breath. Scout Duncan Kerr, ever ready to wield his Bowie knife, advanced to the creek bed and searched around for more trophies. There, he found the body of One Eye. “Some of the boys had scalped him,” Kerr recalled, “but they either did not understand how to take a scalp, or their knives were very dull, for they had commenced to take the scalp off at the top of the head, and torn a strip down the middle of the neck.” Kerr continued beyond the creek and a short distance away found One Eye’s wife sitting alone in a buffalo wallow. He recognized her; for she had been with One Eye and Minimic when they carried the message from the chiefs to Fort Lyon. He described her as “a lively, sprightly, mischievous, little thing, that fairly worshipped her Chief One Eye.” He walked up and put his hand on her head.

“How de do Dunk,” she said, “me heap dry. Give me some water.”

They spoke in Cheyenne, and Kerr asked if she were seriously hurt. She pulled back her blanket and showed him “a ghastly wound in her side, through which the entrails were protruding. The wound must have been caused by the fragment of a shell,” concluded Kerr. “I gave her a drink of water, and left my canteen. As I turned to leave, she took my hand to detain me, and begged me to shoot her with my gun.” Kerr couldn’t do it, he said, “for I had known her a long time.” He walked away while she covered up her head and began singing her death song. The scout met another soldier nearby and pointed her out to him. He told the man that he had just wounded an Indian but had fired his last shot and could not finish the job. Kerr asked him to “creep up behind the Indian and shoot him in the back of the head.” The crash of the gunshot echoed in the crisp air as Kerr strode away.6

When Private Chubbuck left the wounded Captain Talbot, he rode off “between two fires,” dodging bullets from Indians and soldiers. He failed to find the doctor. When he was returning across the dry creek bed, an Indian rose and shot his horse from under him. Chubbuck tumbled to the ground and sought shelter. He fished for his cartridges, but found to his horror that his pouch was empty. He had been so excited, he “could not tell when he had shot his eighty rounds of ammunition.” He extricated himself from that tight spot and made his way downstream to the camp. Somehow the sun had already traversed the sky and it was getting dark when he stumbled in, so overwrought that he “could not remember what he did afterwards.”

The battle upriver unfolded in a staccato series of starts and stalls. Lieutenant James D. Cannon, accompanying Major Anthony as adjutant, rode along the north side of the creek and described the haphazard nature of the battle. One company would ride up to the bluffs above the creek, dismount, fire, and dodge along the banks until the Indians got out of its reach. “Then the dismounted cavalry would be ordered to mount and renew their charge. In the meantime another company would often pass them and get in ahead and dismount to commence their fire the same as before.”7

Little direction was given the men, and the battalion commanders appeared less involved in the decision-making than the company commanders. All of this would have implications for what happened at Sand Creek.

1 “Sand Creek Massacre,” 151, 223.

2 “Sand Creek Massacre,” 143, 149-51; Coffin, Battle of Sand Creek, 20.

3 Howbert, Indians of Pike’s Peak, 101–02; Shaw, Pioneers of Colorado, 81–82; Chubbuck, “Dictation. Sand Creek,” 2; Coffin, Battle of Sand Creek, 19–20, 30; Sand Creek Massacre Project, 130–34. Archaeological investigations showed little evidence of Indian resistance in the village, which confirms observations that it was nearly deserted before the soldiers got into it. The soldiers found few weapons there. This does not mean the Indians were unarmed; it means, as the narratives tell us, that they had plenty of time to gather their weapons before leaving.

4 Coffin, Battle of Sand Creek, 20–21.

5 “Chivington Massacre,” 68, 73; “Sand Creek Massacre,” 70, 207-08; Howbert, Indians of Pike’s Peak, 103; “Massacre of Cheyenne Indians,” 6, 17; Sand Creek Project, 234; Williams, Through the News, 274; Cree to Shoup, December 6, 1864, Sayr to Shoup, December 6, 1864, Shoup to Chivington, December 7, 1864, OR 41, pt. 1, 956-59; Chubbuck, “Dictation. Sand Creek,” 2; Shaw, Pioneers of Colorado, 82; Breakenridge, Helldorado, 49-50.

6 Roberts, “Sand Creek,” 430.

7 Chubbuck, “Dictation. Sand Creek,” 2; “Sand Creek Massacre,” 110–11.