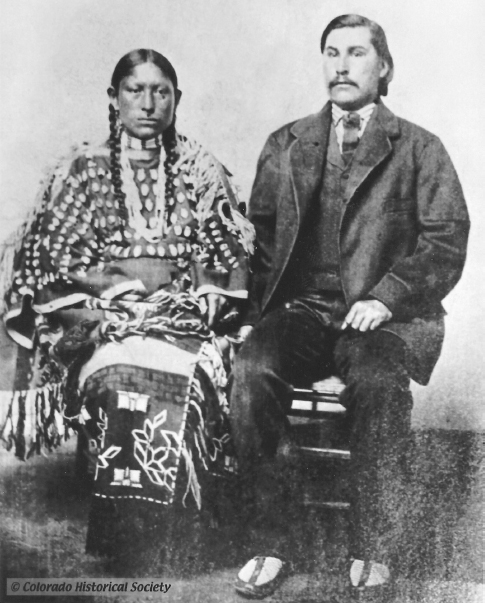

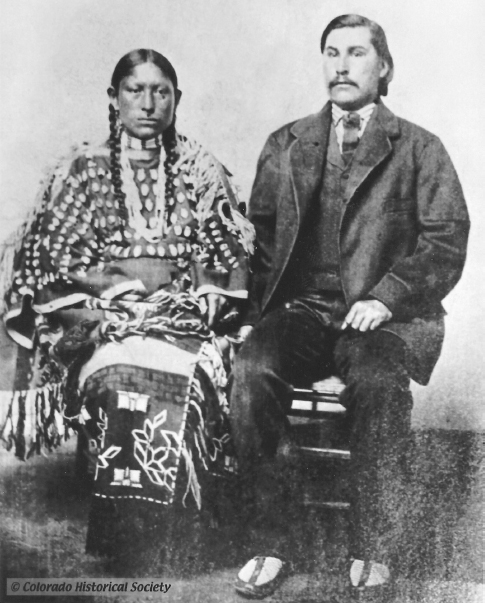

George Bent, the mixed blood son of William Bent and the Cheyenne, Owl Woman, offered the most complete description of the Sand Creek incident from the Indian perspective. History Colorado, Denver, Colorado

Eyewitness testimony provided the foundation of the three hearings about Sand Creek. Although a significant portion of the testimony was not from actual eyewitnesses, but from so-called experts or other interested parties, the fact finders were supposed to build the base on a rigorous examination of those who had seen the events with their own eyes. After all, the American jurisprudence system, including military courts, is built upon eyewitness testimony.

There is little that is more convincing to a jury than a witness who is confident, consistent, and certain that he saw what he saw and that he heard what he heard. According to the U.S. Supreme Court, the “level of certainty of the witness” was usually the most important factor in gaining a conviction. Psychologists who testify about the memories of witnesses, however, claim that “an eyewitness’s confidence is not a good predictor of his or her identification accuracy.” In fact, mistaken eyewitness identifications confidently presented to the jury are the main cause of more than 75 percent of wrongful convictions.1

A large body of research demonstrates that eyewitness testimony is not as reliable as we think. According to Professor Richard Wiseman, “the truth of the matter is that, without realizing it, we tend to misremember what has happened right in front of our eyes and frequently omit the most important details.”2

A classic example of this phenomenon is the “invisible gorilla” experiment. One version of this at Cornell University had students watch a one-minute film with two basketball teams, one wearing white uniforms, and one wearing black. The teams passed a basketball back and forth and the students were asked to count the passes. In the middle of the short movie, a student in a full-body gorilla suit walks into the middle of the players, faces the camera, thumps her chest, and walks off after spending about nine seconds on camera. The actual number of basketball passes was irrelevant because the real test was to see how many people saw the gorilla. One might think such an interruption in the middle of the scene would be like a pie hitting the viewer in the face. In fact, fully one-half of the witnesses saw nothing but teams passing a basketball. When asked if they saw the gorilla, many answered, “A what?”3

A related phenomenon is referred to as “weapon focus.” It would be like a witness in the gorilla experiment seeing only the gorilla and none of the basketball players. For example, one test involved a staged fight by two students. The test ended with a gun held by one of the students going off and the other student falling to the floor. The teacher, a German criminologist, halted the proceedings, explained the test, and quizzed the students about what they had seen. Most of the students could not recall who had been involved in the “fight,” what the students looked like, what they wore, or what they had argued about only a few minutes after watching the test. What they did remember, however, was the gun. Their minds had focused on what they believed to be the most important issue—and forgot much of the rest.4

Research psychologists have been intensively studying the reliability of eyewitness testimony since the early 1980s. The studies have included staging mock crimes and asking the witnesses to identify the perpetrators from photos, testing interviewing techniques, and trying to learn if eyewitnesses could be misled by questions after the event. One test conducted on television staged a purse-snatching event and asked viewers to identify the thief from a six-person lineup. Some 1,800 of the 2,000 respondents identified the wrong man. The studies demonstrate that eyewitness testimony can run the gamut from reasonably accurate to completely worthless.5

So what does all this say about memories? If every memory can be called into question, how does that affect the memories of the Sand Creek participants of their own actions and of the actions they witnessed?

We have already read how some of Edward Wynkoop’s recollections changed over time. Let us consider George Bent, who provided about the only surviving testimony (with the exception of short statements from Edmund Guerrier) we have from the Indian side of events. Bent corresponded voluminously with George Bird Grinnell and George E. Hyde during the first two decades of the 20th century. His letters are a treasure of information about Indian life on the frontier during the mid-1800s. However, they were written four and five decades after the events.

Bent wrote twice to Hyde about the number of Arapaho who were in the Sand Creek camp. In March 1905, he claimed there were 15 lodges of Arapaho and only four individuals managed to escape. Eight years later in April 1913, he wrote that there were only seven Arapaho lodges in the camp and that three individuals escaped. As to the number of Indians captured, Bent wrote Hyde in March 1905 that Colonel Chivington took nine prisoners (six women and three children). In October 1916, Bent wrote to Grinnell that the soldiers captured three women and three children—two Cheyenne women and two children from the lodges, and one Arapaho woman and one child from the sand pits.

In the winter of 1865, many Indians were raiding along the South Platte River. There, they attacked and killed a band of soldiers, or ex-soldiers, heading east. According to Bent, among the soldiers’ possessions were scalps of Indians who had been killed at Sand Creek. In March 1905, he told Hyde they found two scalps. A year later, he wrote and added information that the two scalps belonged to White Leave and Little Wolf. Seven years later in December 1913, Bent wrote to Grinnell that only one scalp had been found, and it belonged to an Indian named Coyote.

Bent offered differing numbers for prisoners and scalps. Which should we accept as correct, and why? It does not appear that Bent had anything to gain or lose by relating these recollections. Instead, his letters demonstrate a malleable memory that subconsciously changed with each retelling. Different motivations may have influenced Bent’s 1913 letter to Hyde that 53 men and 110 women were killed at Sand Creek. Contrast those numbers with Colonel Chivington’s 500, or John Smith’s significantly lower 80. Bent did not remain in the area to do any counting. Instead, he garnered the numbers from the reports of others who may or may not have had their own incentives to inflate or deflate the casualty figures.6

George Bent, the mixed blood son of William Bent and the Cheyenne, Owl Woman, offered the most complete description of the Sand Creek incident from the Indian perspective. History Colorado, Denver, Colorado

We like to believe that our memories are exact accounts of what we witnessed, but that is not the case. According to psychology professors Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons, “What we retrieve often is filled in based on gist, inference, and other influences,” more like a vague melody than a digital recording. “We mistakenly believe that our memories are accurate and precise, and we cannot readily separate those aspects of our memory that accurately happened and those that were introduced later.”7

1 Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons, The Invisible Gorilla: How Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us (New York, NY, 2009), 111-12.

2 Richard Wiseman, Paranormality: Why We See What Isn’t There (Lexington, KY, 2010), 72.

3 Chabris and Simons, Invisible Gorilla, 6-7.

4 Wiseman, Paranormality, 71.

5 Ibid., 72; Kathryn Foxhall, “Suddenly, a Big Impact on Criminal Justice,” American Psychological Association (January 2000), no. 1, accessed January 29, 2014, www.apa.org/monitor/jan00/pi4.aspx.

6 Bent, “Letters of George Bent to George E. Hyde”; George Bent, “The Letters of George Bent to George Bird Grinnell, 1901-1918.” Southwest Museum, Los Angeles, CA.

7 Chabris, Invisible Gorilla, 62–63.