As demonstrated, our memories are altered by a multitude of conscious and subconscious factors that can lead to inaccurate history in a natural world made up of nuts and bolts reality. It should come as no surprise, then, that all of the processes influencing our brains also have an impact or influence on what some of us might consider the supernatural world.

One year after the Sand Creek fighting, a buffalo hunter named Kipling Brightwater claimed to have seen a band of Cheyenne camped on the site. He sent his partner out to talk to them, but no one was there when the man arrived. Although the man sent to investigate did not see anything, he “felt that something very wrong had gone on in the area.” Brightwater reported his experience at Fort Lyon and soldiers investigated but found nothing. The next year, however, Brightwater and more hunters found themselves back in the Sand Creek area. This time around he claimed he saw Indians, tipis, animals, and fires. According to Brightwater, he rode closer to investigate and the entire assemblage simply disappeared into the mist. The perplexed hunter later explained that the only thing he heard was “the sound of a woman crying out in mourning.”

In 1911, a local woman said she was traveling near the site when she said she heard crying, but a search turned up nothing. Similar stories were told for the next hundred years. In the 1990s, visitors to the area were said to feel pain, anguish, and grief. Even members of archaeological teams searching for the village site allegedly felt “overwhelming senses of grief and sadness.” Recent visitors to the area have reported being overcome with such feelings. But do they have anything to do with the supernatural, or are they merely human emotions?1

Don Vasicek, who made a documentary film about Sand Creek, said in an interview with Ghost Story Magazine that he was overcome with emotions on his first visit to the field. Bill Dawson, the rancher who owned the land where the fighting was said to have taken place, gave Vasicek a tour and shared his interpretation of events. “At that moment,” claimed Vasicek,

I saw Colonel John M. Chivington, on a dark-colored horse, with his saber drawn, thrashing down this butte into Sand Creek leading a charge right into the heart of the Cheyenne and Arapaho village. I saw his flaming eyes, orbs of hatred and terror. It was at that point, I felt coldness penetrate my body. I shivered. I rubbed the back of my neck. It was rigid. I closed my eyes. I didn’t want to look anymore. I could hear gunshots, the thud of rifle butts colliding with human heads, sabers slashing through the air, people screaming, and I could smell globs (sic) gun powder.”2

As we know, however, soldiers testified that they had walked into the Indian camp without any sabers in play.

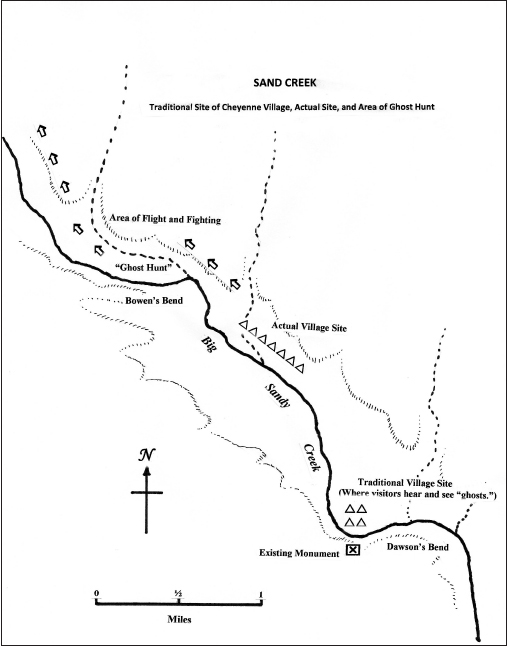

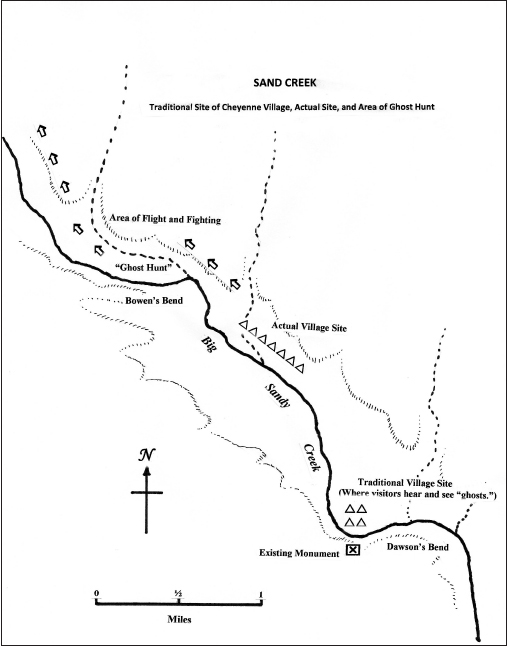

Even more than a place of personal emotional impact, the Dawson’s Bend site has taken on spiritual connotations. A chief of the Cheyenne Council of 44 named Laird Cometsevah visited the site many times over the years and performing sacred rituals there. He claimed to have “heard the voices of children, of mothers, crying for help.” Because he heard voices he “knew that’s where Black Kettle’s people got killed.” Years earlier, Cometsevah had accompanied the a Cheyenne named Sacred Arrow Keeper to Sand Creek, where he consecrated soil to make it “Cheyenne earth.” “Spiritually and religiously,” Cometsevah explained, we “claimed that spot for the Cheyenne.” “The Arrow Keeper wasn’t wrong,” he insisted. “I wasn’t wrong. That’s exactly where the massacre happened.” Unfortunately, no physical evidence of the fighting has ever been found at that site. In what appears to be an exercise in circular logic, the village had to have once stood at Dawson’s Bend on Sand Creek because a sacred ceremony was performed there. Why was it performed there? Because that’s where the village was located.

Many Cheyenne, however, could not accept the fact that the traditional village site contained none of the artifacts that should have been associated with a village and a battle. In addition, archaeological surveys demonstrated that the village and the fight took place at least one to three miles upstream. “They’re calling our ancestors liars,” was Cometsevah reply. Of course Cometsevah’s ancestors were not being called liars, but not being a liar is not the same thing as being accurate.3

The old monument on the bluff overlooking the traditional village site.

Author

The reality is that the deficient memories of everyone involved wreaked more than enough havoc on the historical truth of what happened at Sand Creek, and where it happened. The simple fact is that Vasicek, Cometsevah, and hundreds of other visitors were mistaken about where the village was located and the fighting took place. Black Kettle’s village was not on the spot where these people stood and envisioned all the horrors of warfare and heard weeping women and crying babies.

The lack of archeological evidence did not stop the National Park Service (NPS) from acting. While the NPS was negotiating the purchase of the land, a team of professional archaeologists inspected the area and found that actual site of Black Kettle’s village was a mile to a mile-and-a-half north of the area where the so-called spiritual encounters had occurred. Despite this information, the NPS constructed its visitor center near a stone monument that sits atop a bluff overlooking Sand Creek—but nowhere near the site where the actual Cheyenne village once stood. But the Park Service now owns the land, so it serves a purpose (and brings to mind the famous movie line “If you build it, they will come”).

Chuck Bowen grew up on a ranch a few miles north of the NPS site. He spent many years searching the the area and discovered numerous village- and battle-related artifacts. He and his wife Sheri intensified their efforts to find the real site of the battle after 1993, when the Colorado Historical Society began inspecting the area. By 1997, they were hard at work with metal detectors, history books, and maps, and as a result assembled a remarkable collection of more than 3,000 relics—all found on Bowen property starting about two miles northwest of the traditional site at Dawson’s Bend.

When the NPS entered the picture as a result of a 1998 public law, Chuck Bowen suggested to park representatives that the U.S. soldiers got their first view of the village from the bluffs near the monument above Dawson’s Bend, but that the real village site was nearly two miles farther north. That area, he explained, was where they should begin looking for artifacts. The NPS located a concentration of artifacts a mile and more north of Dawson’s Bend, which they soon determined was the actual site of Black Kettle’s village. The artifact patterns also indicate that the village was not drawn up in a tight circle as is usually depicted, but was instead strung out along the course of the creek for at least a mile. The archaeologists noted that the “absence of definitive artifacts of resistance” was consistent with the Indian accounts that the attack came as a complete surprise.4

If the lack of weapon relics in the village suggest the Indians were surprised and did not put up much if any of a fight, it also supports what a number of soldiers claimed: The Indians had already vacated the camp before they reached it, they had simply walked in, and that there was no battle in the village proper.

Thus, the relativism—knowledge and truth existing in relation to historical context—and its parent, postmodernism, are reflected even in scientific study.

1 “Mystery History the Paranormal and More,” http://mysteryandhistory.blogspot.com/2011/05/ghosts of-sand-creek.html, accessed December 17, 2013; “The ghosts of Sand Creek,” http://www.examiner.com/article/the-ghosts-of-sand-creek, accessed December 17, 2013.

2 “Donald L. Vasicek: The Zen of Writing,” http://donvasicek.com/uncategorized/1516/, accessed December 18, 2013.

3 Kelman, Misplaced Massacre, 126, 140–41.

4 Jerome A. Greene and Douglas D. Scott, Finding Sand Creek History, Archaeology, and the 1864 Massacre Site (Norman, OK, 2004), 96.