chapter two

First Cut

The body dead is, in a way, our world’s greatest secret. We see always flesh in motion, animated, disguised beneath its clothing and uniforms, its signals and armatures, its armor of codes and purposes. When do we look at the plain nude fact of the lifeless figure? Pure purposelessness—and thus, in the absence of the spirit, strangely and completely present. Never having a chance to see it, to assimilate our horror of it and go on to actually look, how would we know that the lifeless body is beautiful?

MARK DOTY, HEAVEN’S COAST

In the morning we have our first lecture before going into the lab. I’m full of nervous energy. I’ve been anxious about dissecting a body since I decided to become a doctor, and sorting through the bone box has only made that anxiety more real. I wake up before my alarm sounds—rarest of rare occurrences in my life—and am unable to quiet my mind. I turn on the coffeemaker, but when I return to fill my mug, I realize I forgot to put the beans that I ground into the filter. Clear hot water fills the carafe. As I walk across campus to the medical school, my mind keeps turning to the dead bodies I have seen at funerals, stiffly clothed and made up, and to my surprise at watching those mourners who reach out to touch the bodies, kiss their cheeks, and hold their hands. If those touches of kindness have unsettled me, how will I respond to the actions I will be asked to perform?

As my classmates and I greet each other and fill the lecture hall, I try to project comfort and nonchalance—as if, with my new pens and empty notebooks, this is any other first day of school. In fact, I’m full of jitters and wonder how I’ll be able to focus on an entire morning of lecture.

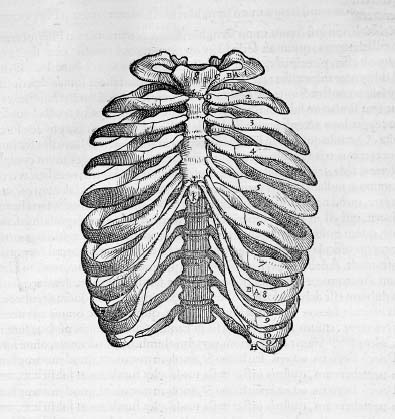

Our professor, Dr. Ted Goslow, brims with enthusiasm at the start of this new semester, and he speaks for an hour and a half on the intricacies of the thorax—the section of the body between the neck and the abdomen that is enclosed by the ribs and contains the heart and lungs. “When you get just below the skin,” he explains, “you’re going to see two sets of important muscles, the pectoralis major and minor, or ‘pecs’ as you bodybuilders may know them.” The class chuckles obediently, and Goslow continues, explaining what we’ll encounter as we uncover layer after layer of the chest. “Between the ribs, three layers of intercostal muscles work in conjunction with the diaphragm to expand the rib cage and fill the lungs with air.” Once we remove our cadaver’s rib cage, he tells us, we’ll see the lungs, and beneath the lungs we’ll find the heart and its great vessels. We must cut these with care, he warns, in order to remove and study the heart. “By the end of today, you’ll hold a human heart in your hands. It’s amazing!” Goslow says. Until this point I had been diligently taking notes in the first pages of my fresh notebook, but as he conjures this image, I stop and sit quietly, a little slack-jawed.

Suddenly we are talking about reaching the cadaver’s heart and lungs, and I have barely begun to get used to the idea of the initial cut through a dead body’s skin. Friends of mine who’d finished medical school had alluded to the pace of the course when I asked about acclimation. “You don’t have much time to process,” one friend said. “There’s just too much to get done.” This class would be a baptism by fire. We would be given driving directions and a car with no brakes. Twice a week we would spend seven hours a day in the anatomy lab, where we could make right turns or wrong turns, but we would most certainly be moving. Dr. Goslow’s tone is encouraging, yet also utterly straightforward: “This will be fascinating, frustrating, and technically and emotionally difficult, but it will also get done. We don’t have much time, so get started.”

Led by Dr. Goslow, my classmates and I travel en masse to the anatomy lab from the lecture hall and enter a narrow hallway filled with rolling racks on which hang scores of white coats. An additional group of instructors is waiting for us in the hallway—a mix of graduate students and junior faculty members who will supervise our dissections and provide us with much-needed guidance. One of the instructors tells us the three-number sequence to the combination lock on the wide metal set of double doors to the lab hallway, numbers we will all punch in at various hours as we come in late or early over the course of the semester.

Immediately after the announcement of the combination, I’m too nervous to recall a single one of the numbers. Already the sharp smell of the formalin-and-alcohol embalming fluid is washing over us. We try to ignore the smell, as well as the doorway that opens into the lab at the end of the hall. Instead we focus intently on the sizes of the white coats. None of us seems to be able to find the right size. We laugh nervous laughs, until we finally manage to slide our arms into jackets whose cuffs reach our wrists and there is no longer any reason to linger in the hall.

The view into the lab is jarring—eighteen white body bags atop stainless-steel rolling tables. There is no way for me to mistake the forms for anything other than human, but the fact that the bodies are enclosed and airless also makes them unmistakably dead. As we enter, we are supposed to grab our name tags off the table to our right and clip them to our jacket pockets. I forget and head mechanically toward the table to which three of my classmates and I have been assigned during lecture. I am hoping for a woman. Perhaps I want to learn about my own interior. Perhaps I think I cannot take anything that makes this experience more foreign than it already is.

I try to assess the form on the table without touching it, only looking at the way the thin, white, zippered plastic bag encases it, and I decide it must be a female form. Many of the bodies are unquestionably male, due to postmortem erections that make an odd tent shape of the bag. I have heard jokes about anatomy groups naming their cadavers “Woody.” At the moment it is hard for me to picture—I feel far from being able to joke about any of this.

You’ll hold a human heart in your hands, Goslow had said. But by the time I enter the lab, I have forgotten the promise of discovery and am focused only on his more practical advice: “Some reflex pathways we can control, like our eye-blink reflex, and some we can’t, like our knee-jerk reflex. This explains that our brains sometimes overpower our wills. So if, once we go down to the lab, you see someone talking but you can’t hear them, sit down, because it means you’re going to faint.”

I am the first of my group of four to arrive at our table but am joined quickly by Tripler, a bright and wonderfully quirky exballerina; Tamara, a shy and often-absent twenty-one-year-old whom I will know little better on the last day of lab than I do on the first; and Raj, a recent biology major who cannot wait to begin dissecting. Like Tamara, Raj is twenty-one and has come to medical school straight from college. Tripler and I are both twenty-eight, having followed circuitous paths to med school. A no-nonsense intellect, despite her swinging blond ponytail and chirpy voice, Trip studied at Harvard and Oxford and has a master’s degree in the history of medicine, which allows her to pipe up with often obscure but always fascinating historical tidbits over the course of the term.

“Listen to this, you guys,” and some ridiculous but interesting story will follow. “In the 1700s this English country doctor thought that the dairymaids in his town might be immune to smallpox because they were lovely and smooth-skinned despite their constant exposure to cowpox. So, to test this, he inoculated some poor kid with the cowpox pustule of a dairymaid. Six weeks later he injected the kid with smallpox, and he didn’t get it! Hence the first vaccinations!”

In the first nervous moments of lab, however, even Trip’s merriment is muted. All four of us surround our table while other groups are still trying on coats and looking for their table numbers. Tripler and Tamara and I are quiet, our gazes bouncing from the body bag in front of us to one another, to the hushed and filling room. Raj is pulling small tools out of a drawer, chattering about dissections he’s done in his biology classes: fish and lambs, piglets and cats. He is the only one who is excited to begin.

Once all the students have gathered around the eighteen tables, the instructors disperse among us to demonstrate dissection techniques. Dr. Dale Ritter comes to our table. He’s an affable and frighteningly knowledgeable young member of the faculty, with an easy laugh and an unmistakable southern twang. When he unzips the bag covering our cadaver, we discover that she is indeed female. Her torso is covered with a damp white cloth. Her hands, feet, and head are wrapped in a translucent, cheeseclothlike material and then enclosed by tightly tied plastic bags. This elaborate wrapping, Dale explains, is to protect those parts of the body from desiccation until we begin our study of them. He adds that their coverage also helps depersonalize the body. The hands, feet, and head are parts of the body that are instilled with character. They can most quickly conjure up an individual life. But I cannot take my eyes off the woman’s arms. They are covered in age spots and thin and long. They have skin that drapes from the bone. They are surely the arms of an old woman who has spent time in the garden or at the lake. They are the arms of my grandmother, which I massaged for a week before coming to medical school as she lay in bed following a stroke.

I see that she is not my grandmother when Dale pulls back the sheet to reveal gray hair matted between the woman’s legs. In March my grandmother had laughed and bragged to me that “one of the best things about getting old was not having any body hair.” She didn’t have “a speck of pubic hair” left. Was this woman younger than my eighty-year-old grandmother? I wonder. Was her death expected? Over the course of the next few months, would I learn things about her history from looking at parts of her that no member of her family had ever seen? Sutures from an accident, an empty space where her uterus should be, atherosclerotic arteries, a missing gallbladder or appendix? I would certainly learn some things about her that they would never know: the exact shape of her stomach, the marks left by pollution on her lungs, irregularities in the paths of her veins, the precise heft of her brain, the look of the inside of her eye.

Dale tells us we must spray our bodies with a wetting solution to keep them from drying out and making dissections stiff and difficult, if not impossible. He is all business. I feel as though I’m in two places at once. I listen intently to Dale, relying on his practical words to ground me in this most preternatural of moments; however, I’m also staring at the cadaver, wondering how I—how any of us—will be able to make the first cut into this woman’s body.

As it turns out, by either coincidence or design, it’s a leap that we do not have to make. Dale props our cadaver’s right shoulder up on a rectangular block of wood and pulls a bright ceiling lamp over her to light her upper arm. “I’m just going to do a quick demonstration of dissection technique,” he explains as he cuts a confident six-inch line and then perpendicular three-inch lines at either end of it, making a wide H. Then he pulls the skin up and shows us the fascia beneath, a yellowy, loose, fatty, connective tissue. We will discover that it is at times thick and greasy and globular, at others webby and thin. Below it we see muscle, gray and well defined, with clear linear fibers that make it look more ordered and purposeful than the fascia overlying it.

As Raj has discovered, several instruments are kept in drawers at the head and foot of each metal table, and Dale shows us how to use the scalpels to cut quickly and easily through skin. So sharp is the scalpel that you practically trace rather than cut with it. It is immediately evident how fast and irreversible the scalpel is, and Dale turns to slower, more cautious tools, which will therefore be those we choose most often. Scissors are rarely used to cut but are much more often inserted, closed, into spaces beneath skin or between arteries, or veins, or organs, or nerves, and then opened, to spread away fascia and connective tissue, separating out the structures intended for study. Two types of forceps are available, one with thin, blunt ends and one with a “rat-tooth”—a metal V on one end that fits into a corresponding notch on the other—to grasp and pick away extraneous matter.

We wear latex gloves, and Dale notes that, more often than not, our hands and fingers will be our most valuable and effective tools. He slides his finger into the incision he has made and then beneath the skin. Then, with remarkable ease, he makes an authoritative sweeping motion, which divides the layer of skin and fat he now holds between his finger and thumb from the gray muscle below it. He peels the skin away, revealing a section of overlapping muscles of the upper arm. The emergence of the muscles is an introduction to the promise of discovery, of clarity beneath disorder.

Before we begin to try these techniques ourselves, each group is called into another room for a prosection, a demonstration of what we are instructed to uncover in our impending dissection. This will be a far more elegant version than our efforts will yield. The demonstration cadaver is the body of a big man with tattoos on both biceps, which have blurred into large blobs of inky blue. The skin of his chest is gone. We watch Dale peel back the man’s pectoralis major and minor, then lift off a large, precut square of rib cage revealing gray-blue lungs and a reddish diaphragm. He explains that we will use a saw to cut through the ribs. The saw, like the light, pulls down from the ceiling. I can see through the window to the lab room that groups who have left the prosection are already beginning to saw. Thin curls of cartilage and muscle are wheeling off the blade, and the dust of bone is breaking the light in the room into rays. The dust in the air smells like the dentist’s office. I am eight years old and have fallen mouth-first into the concrete, with my friend Myla Wilson on my back. The dentist is grinding my teeth down.

I am afraid that I won’t be able to do this.

The Essential Anatomy Dissector, our textbook version of a road map for the term, reads simply, “Make the incisions shown in Figure 1.1.” The figure is a drawing of a naked woman, apparently in her thirties or forties, who looks straight off the page with open eyes and appears to be alive. She is, however, conveniently in what we have learned is called “anatomical position,” which means that for this dissection she lies faceup, with her arms at her sides and her palms facing the ceiling. She has a full head of hair, which our cadavers, we can tell through their shrouds, do not. Their heads have all been shorn, giving them a look that is part androgynous and part awful, like prisoners of war. When I mention this to a friend who is already a doctor, she tells me that the cadavers in her lab still had their hair. Imagining how the hair would look after weeks of wetting solution and bone dust and how, early on, it might make them seem more human, I prefer our cadaver as she is.

My sense of the humanity of our cadavers is evasive and shifting. One of the strangest things about dissecting a human body is the difference between a human body and a human being—in some ways readily identifiable and in others barely perceptible. Everything tangible that is human is present in our cadavers. Their dead body parts are structurally identical to our living ones. Our cadavers are undeniably human. Each bears distinguishing traits that evoke the life of an individual. Once her hands are uncovered, we learn that the woman at another group’s table has lavender polish on her fingernails, and, as a result of that lone variation, we find ourselves wondering about her: Did she have a weekly manicure appointment that she never missed over the last twenty years, for vanity and to share confidences with her manicurist? Did she live in a nursing home, which had a Beauty Day that she initially resisted, eventually acquiescing, only to love the experience of her first manicure but hate the old-lady color? Did her granddaughter paint her nails on her annual visits, despite the old woman’s inability to recognize the girl after the ravages of Alzheimer’s? Was the polish a preparation for a dinner date, an anniversary, a wedding, a funeral?

We can make cuts through our cadavers and peel their skin away. We can trace the paths of their circulatory systems and marvel at the fragility of vein and strength of nerve. We can curse the difficulty in finding a tiny artery in the thumb or neck and even laugh at our ineptitudes and mishaps. But the humanity of the body emerges in unexpected moments, and the balance of our voyage of discovery with the voyage of a finished life is sometimes difficult to steady.

Dissection, we will learn, will require us to turn off, in a sense, our connection with this humanity. I cannot say whether for me that is a conscious or subconscious decision, but I do remind myself more than once that my grandmother is alive in Indianapolis. I take a deep breath, and I focus—on the Dissector, on the scalpel and how much pressure is required to go deeply enough to proceed but not so deeply as to do damage. And I do this—this breathing and focusing and gauging and cutting—for hours. The work is slow and deliberate, and this first morning of lab will bleed into the afternoon and then the evening, with all groups progressing forward, little by little.

The skin of the chest pulls back easily after we have made the incisions, and the body opens like a book. Thumbs inserted at the midline of the chest above the sternum, or breastbone, pull back both sides, like the covers of a text, revealing the ribs and the muscles that connect them. In the female cadavers, the breasts, firm and set in an unchanging shape by the embalming process, remain attached to the skin. They are removed from the body when the folds of skin over the chest are peeled away and replaced when the skin is pulled back over our day’s dissection. It is as if the breasts are part of a strange vest, as if this marker of gender can, in death, be slipped off or on.

When it is time to cut through the rib cage, none of my group members wants to do it. Neither do I, really, but I do, not to be macho, and not to force myself through something unpleasant or difficult, but because I need to know what I am capable of. I do not know whether I will be able to do it until I do. I am almost surprised when the body does not flinch or cry out when cut. And so, just as the humanity of our cadavers asserts itself in nail polish and tattoos, the inverse of humanity emerges in the body’s utter lack of response to profound wounds.

Instinctively we find ourselves using our own bodies as reference points, as road maps. Perhaps due to her years of ballet training, Tripler stretches and hops absentmindedly in lab from time to time. When we begin studying the motions of muscles, she is brilliant. “What is the action of serratus anterior?” we ask her, already trying to quiz ourselves on the first structures we encounter. She is wrist-deep in dissection, separating out the pectoralis muscles, and instantly lifts her straight arm out to her side, then raises her outstretched hand above her head, saying, “It rotates the scapula when you raise your arm.” We pause, holding our tools still above the cadaver in order to watch Trip’s demonstration. “And it draws the scapula forward when you push your arm forward,” she explains, miming a forward punch with one gloved and messy fist.

We begin this kinesthetic learning without knowing it: We are nervously trying to determine where to saw across the top of the rib cage, as the Dissector instructs us. Tripler reads to us from the textbook, “We go through the manubrium, so we have to find the suprasternal notch,” and we all put our fingers to our own throats and find the thumb-size bony notch at the base of the neck, “and that’s the top of it, and then we keep going down a couple of inches to the angle of Louis—you should feel a transverse ridge on the anterior aspect of the sternum, and that’s where the manubrium ends and the sternal body begins.” I’ve got the notch but can’t find my angle of Louis, and so she has me feel hers, then try again. Ultimately she finds mine for me, putting my hand in exactly the right place. Dissection, we discover, is in part a process of beginning to name parts of our own bodies whose names we have never known. We find a structure beneath our own skin, a place we have toweled dry perhaps ten thousand times and never noticed, and then we uncover it in our cadaver, feel the shape of it, learn its purpose.

To cut away the front of the rib cage and remove it from the body, the Dissector tells us we must cut through, “ribs 2 through 6 just anterior to the serratus anterior muscle.” I guide the saw down the body’s sides. If you put your hands on your hips and then slide them up your sides to just beneath your armpits, your fingers are exactly where the projections of your serratus anterior muscle are. I am sawing alongside where both breasts were just hours ago, down to the sixth intercostal space—the space between the sixth and seventh ribs on both sides. I then saw across the body so that the two parallel cuts meet. To free the top of the rib cage, I have no choice but to go through the manubrium, which I can now locate easily.

I must cut with the bone saw through each rib and through the muscles and cartilage that support them. The saw is imprecise and requires a good deal of force—you have to lean the weight of your own body into it. Sawing through the rib bones is disconcerting; enough pressure must be applied to coax the dull blade through the bone, but too much sends it sailing past the far edge of the rib and into God knows what—whatever is in the space into which we’re entering blindly. The muscle and cartilage are much easier to saw, but, as a result, doing so lacks the distraction that effort affords. The tissue spins off the blade in small bits, which look like tiny roots or fingernail clippings. The cutting doesn’t feel awful or triumphant when I finish; it only feels done, and suddenly quiet, and, after all, there is now the first dark and open space to look into.

With the sawing finished, my lab partners can begin to separate the rib-cage section from the body, cutting through any remaining connections with their scalpels. In the center of the section at the top and bottom is a set of blood vessels that run along the inside of the breastplate. They must be cut before the rib cage is removed. When my partners do so, we can lift the rib cage free. Its outline dips down in the center to the midline sternum and then flares out at both top and bottom to either side with the rows of ribs. Disembodied, the rib cage looks like a butterfly.

Most of us, I think, harbor an ingrained, innate aversion to doing willful harm to the body. Of course, such harm is regularly done: adolescents shoot each other over vapid allegiances, men kick their pregnant wives, children smash beetles to bits under their heels. There is an internal restraint, however, that must be overcome, by rage or fear or sheer will, before we will do harm to a body. And so, watching the flesh coil away, the bone rise above the chest as dust, I feel that feeling you get when you think of the moment your teeth broke as a child or you hear about a fracture in which the splintered bone pierced the skin—an inescapable feeling of wrong. Tamara cuts through skin, and I feel the instinct to place my hand on the cadaver’s arm: This will only hurt a minute. This will be over soon.