chapter five

Origins of a Corpse

O may I join the choir invisible

Of those immortal dead who live again

In minds made better by their presence: live

In pulses stirr’d to generosity,

In deeds of daring rectitude, in scorn

For miserable aims that end with self,

In thoughts sublime that pierce the night like stars,

And with their mild persistence urge man’s search

To vaster issues.

GEORGE ELIOT, “O MAY I JOIN THE CHOIR INVISIBLE”

In the semester’s third week, the thoracic dissection has ended and we are ready to begin dissecting the arm. The muscles that anchor the arm to the body stretch across the shoulder and onto the back. Therefore, in order to continue with the dissection, we must turn our cadavers over. The bodies are stiff and very heavy and require someone to hold the legs, another person to hold the head, someone to guide the midsection as it turns, and a fourth person to make sure that the arms turn with the body. Otherwise they would catch and end up twisted beneath the torso’s weight. The ankles no longer bend, of course, and so the feet are insistently flexed, preventing the legs from lying flat on the metal table. The neck poses the same problem—the head does not turn, and so when the body is rotated onto its stomach, the face must support the weight of the head. From just such pressures, various parts of the bodies flatten, forever marked by their postmortem positions.

The first cadaver I ever saw was on a tour of a different medical school, when I was applying to programs. The man’s body lay faceup, but his nose was smashed to one side from the back dissection, which had preceded all others. Somehow that felt like a terrible insult to me, and whenever we turn our cadaver, I hold her face gently in my palm, making sure she rests on her chin rather than her nose, or some other spot that is equally likely to bend. It is illogical. We have at this point removed her heart and lungs from her body, tying them in a brown-black garbage bag and laying them on the shelf below the table for later study. Her rib cage falls to the table as we turn her, and one of her removed breasts lies out to the side of her, facing the ceiling as she lies facedown. Holding the cadaver’s chin does little to protect the body’s form, but as our actions render her less and less whole, it seems somehow important to preserve whatever human shape we can.

The stiffness of the cadavers comes from rigor mortis, prolonged by the formalin embalming. Several hours after death, the body loses its pliability and assumes a state of contracture, where the muscle tissue is abnormally shortened, preventing any kind of passive stretch. It is the extreme version of the morning stiffness any one of us might feel upon rising. And whereas we can stretch and lengthen our muscles, this action requires energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the powerhouse molecule of the human body. The body works constantly to provide energy to each of its cells. When we die, the production of ATP stops, but a bit of a stockpile remains. So for several hours the dead body can be manipulated and maneuvered. After that, rigor mortis sets in.

Usually, some fifteen to twenty hours postmortem, as the body begins to degrade, the rigor mortis begins to subside. Muscle proteins are destroyed, releasing potent enzymes, which cause cells to burst in a process called lysing. The connection between muscle filaments is gradually lost, and the body regains some pliability. In our cadavers, however, the formalin embalming process cleanses the body of those enzymes, leaving it in a perpetual state of rigidity.

The back portion of the dissection goes quickly for our group. The Dissector instructs us to cut one long line through the skin at the body’s midline from neck to tailbone. We then make three horizontal cuts: one following the shape of the shoulders, one just beneath the shoulder blades, and one arching across the top of each buttock. The Dissector’s illustration looks like a picture from an old cookbook showing the regions of the cow from which various cuts originate.

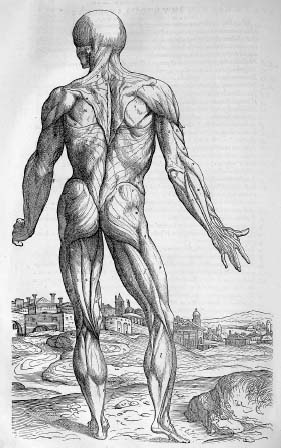

We peel back the skin and clear away some of the fascia to reveal the superficial muscles of the back. They attach the arms to the central skeleton. The muscles are big and broad, with serious-sounding names: latissimus dorsi and trapezius—large, flat, triangular muscles with extensive ranges across the terrain of the back. We are instructed to “reflect” them, cutting through them at a carefully chosen point and folding the muscles back to see what lies beneath.

The effect is somewhat like opening a triptych, with the muscles swung wide to reveal their undersides and a new layer of musculature, or sometimes bone, beneath. There is always a moment of expectation upon opening, the strange hope of beauty within all that darkness. I think of Fra Angelico painting his famous frescoes beneath the floors of the San Marco Convent in Florence. We see them now, with tricks of light and mirrors, but might they have remained unfound and therefore unseen? Nature is full of dazzling beauty in unexpected recesses. As his lover dies of AIDS, Mark Doty writes about the interior of a crab shell:

…A gull’s

gobbled the center,

leaving this chamber

…open to reveal

a shocking, Giotto blue.

Though it smells of seaweed and ruin…

Imagine breathing…

surrounded by the brilliant rinse of summer’s firmament.

What color is the underside of skin?

Not so bad, to die,

if we could be opened into this—if the smallest chambers

of ourselves, similarly, revealed some sky.

Compared to dissecting the thorax, the dissection of the superficial back muscles so far seems simple. As we gain more of a sense of how much time is required for each dissection and the study of it, we grow increasingly aware of how limited our time is and how many tasks lie ahead. So we quickly clean and reflect the muscles, find a couple of hidden nerves, and turn the cadaver on her back again. As we flip the pages in our manual to determine the first steps for the arm dissection, we notice that many groups are still fighting their way through thick clumps of fat to reach the back muscles. The slim frame of our cadaver makes dissection less tedious, more clear. My group feels lucky; we can move ahead into the arm while others still have hours of cleaning and separating ahead before they will be done with their backs. We are also lucky from an emotional standpoint.

The table behind ours, with the large male cadaver and his large heart, is getting angry. One of my classmates, Roxanne, is a spitfire of a twenty-two-year-old who has lived her whole life in Rhode Island. She does her dark brown hair in big curls and wears blush and eyeliner to lab every day. She lives with her college boyfriend, who teaches gym to special-ed kids in a small town nearby and earns extra money plowing snow. Roxanne speaks her mind; I like her instantly.

When she sees us turn our cadaver back over to begin the arm dissection, she lets out an exasperated groan, pushes her hair away from her eyes with her wrist, her gloved hands holding forceps and slick with fat, and says in frustration, “Why does our guy have to be such a flippin’ horse?” The comment flies in the face of the hushed reverence we have felt the lab required. It is perfect. After a quick moment of silence from both our tables, all eight of us break into giggles and wisecracks. We wait for lightning to strike in response to Roxanne’s transgression, and when it doesn’t, we all sigh happily into this new place where laughter is both acceptable and sometimes necessary.

We return to our respective tasks with a recalibration of balance. In college a treasured instructor pulled me aside after I had submitted a particularly dark series of poems in a creative-writing seminar. “You know,” she said, “Shakespeare was great because he wrote tragedy and comedy with equal vigor.” Whether this was advice on writing or a well-meaning attempt to pull a nineteen-year-old back from the edge of writerly angst, the comment resonated then and has continued to resonate for me. Even the most comic moment contains an element of melancholy; even the deepest tragedy harbors a trace of the ironic.

Roxanne’s comment then (and the many equally prescient ones that followed) also granted our work in the lab a kind of honesty and perspective. Dissection is work. The hours are long; the toll on our own bodies is felt in both emotional and physical ways. And what each of us knows is that work becomes mundane and demands a sort of levity, whether the profession is that of store clerk or surgeon, counselor or coroner. “I think we can feel free to break for coffee,” Roxanne says one afternoon, when frustrated with the lab’s slow progress. “It’s not like our guy’s going anywhere.”

Even with the new freedom of humor in class, aspects of dissection remain deeply disconcerting. Beneath each of the dissecting tables in our lab hangs a shiny stainless-steel bucket into which skin, bits of fat, and other unneeded pieces from the body are discarded. The buckets are never emptied over the course of the semester, and we are told to scrupulously place into them anything we remove from the cadaver. The theory is that when the body is cremated at the semester’s end, it will be cremated in its entirety. Perhaps the idea comforts potential donors and their families. To us, however, the buckets are haunting. The collection of contents is macabre, and though we try diligently to place all “scraps” in the bucket, we cannot always do so. Hardened blood from the heart is washed down the sink. Bits of skin and fat clinging to dulled scalpels are discarded. I come to think of the bucket as a gesture, and I try to keep as much of the waste in it as I can.

Before beginning medical school, I had heard of students naming their cadavers, often according to some physical trait. The idea of it struck me as disrespectful, and I was sure that I would resist if my lab partners suggested a name for our body. Whether naming cadavers is a means of participating in a medical-school ritual or a human way to make a connection to the body we are coming to know, I am surprised when the name we give our cadaver emerges so organically that I do not resist it. In fact, I embrace it.

When we first remove the damp cloth over her abdomen, the skin is set in firm, deep creases, so we do not notice right away that she has no umbilicus. But for the creases, the skin is smooth, uninterrupted. Already beginning to be trained in questioning morphology, we try in vain to diagnose: “What kinds of things could lead to no belly button?” Silence.

Even if we had known our embryology then, we wouldn’t have come up with an answer. Umbilic—“the central point.” Placenta—“Latin for cake.” Raj says, “Maybe we got Eve.”

On days when we are all present, seventy-two students huddle over bodies in the wide, white room, and our voices bounce off the painted cinder-block walls. Even at that size, ours is one of the smallest medical-school classes in the country. It is not uncommon for anatomy classes at American universities to take up several rooms, in order to accommodate two hundred or more students, and for faculty instructions to be shown on video monitors mounted in each room. At international schools, where class sizes can number several hundred and cadavers may be in short supply, students may cycle through the lab in rounds. In these arrangements, with sixteen or more students assigned to a single body, the students are essentially only observers of dissections that have been completed largely by staff members.

Sharing one cadaver among four students is a luxury, one to which we have access twenty-four hours a day. Despite spending two entire days each week dissecting with our group members, it is understood that we will not be able to absorb everything we need to learn during that time, so we all routinely make additional trips to the lab. Sometimes the lab harbors a kind of midday clatter past midnight and into the first hours of morning. However, on days with no tests on the horizon, the lab is often quiet, if not empty.

Trip and I occasionally make arrangements to meet one another at the lab in the evenings as the daily lab schedule keeps racing forward. One night we come in to try to get a handle on the coronary arteries, which take the freshly oxygenated blood pumped out of the left ventricle and feed it right back into the muscular heart to sustain its rhythmic beating. The arteries encircle the heart, and as we look for them, we are constantly befuddled. Eve’s vessels are small and difficult to locate. Since the body at Roxanne’s table has a gigantic heart, we zip up Eve’s bag, placing her heart back into the garbage bag that holds her lungs, and head to the table beside us.

Although human anatomy is largely consistent from one body to the next, there is a wide range of what are considered to be variations on the norm. The size of a given structure is one of the most common variables, but shapes and even locations of organs and vessels may differ slightly from person to person and still qualify as unexceptional. For this reason we’re encouraged to study the anatomy of many of the cadavers in the lab. Our knowledge base should therefore be broadly applicable, not specific to the one body we’ve dissected. And yet it is oddly disconcerting to leave Eve and approach the cadaver at Roxanne’s table. The familiarity of Eve’s body grants us a sort of comfort with the accompanying emotional terrain, and this comfort is absent when we reach beneath the table and pull up the plastic bag, from which we take out the man’s heart.

Despite the promising size difference, which we thought would clarify the anatomical structures in the same way the cow’s enormous organs did, this heart nonetheless provides its own challenges. As was true for us with Eve, once the heart is removed from the body, it becomes disorienting. We cannot identify one side from the other, and we spend the first few minutes poking our probes into the aorta and vena cava to determine where the channels lead, in the hopes that we can make some sense of right and left, front and back. In addition, the ubiquitous fat on Roxanne’s cadaver has not spared his heart. A thick layer of globular pericardial fat encases it, making our search for the coronary vessels all the more difficult.

After a frustrating hour in which we have accomplished little, Trip has to leave to teach an aerobics class. “I have them all doing heaps of push-ups now so that I can tell them about strengthening the pectoralis major and minor!” she chirps, and I grin. I guess we have learned something. I walk out with her, having decided to get my anatomical atlas from the trunk of my car and return to try to find the coronary vessels on one more heart.

It’s a beautiful, warm September night, and while we walk to our cars, Trip is regaling me with stories of her pet lovebird, Odette, who used to sit on her shoulder while she worked as a hostess at a New York nightclub. Odette has been losing feathers, and Trip tells me that the vet thinks the bird may have a seed allergy. “I mean, can you imagine?” she wails. “I’m supposed to pick the little green ones out of her food!”

When I get back to the entrance of the BioMed Center, it is dark. As I wind my way through the hall, I pass a few students leaving, but as I head downstairs I find myself totally alone.

As we’ve been instructed, Tripler and I turned out the lights when we left, and so when I walk in to the windowless lab, it is silent and pitch-black. I quickly flip the light switch, and the silence gives way to the buzz of fluorescent bulbs. For the first time, I’m alone in the lab with eighteen dead bodies. I pause in the doorway, take an involuntary deep breath, and hold it. The scene is eerie and disquieting. I feel a little scared and yet know it’s silly: the kind of mixed emotion you feel when you hear a noise in your house at night and are sure it must be nothing but sheepishly check the rooms and closets all the same.

I tell myself I’m being ridiculous, that things are no different than they were just moments ago when Trip and I were here together. I walk decisively over to Eve, then remember that I meant to look at a different heart. As I stand, trying to decide which table to approach, I hear my pulse, fast and regular, pounding in my ear.

Our lab table is in the corner of the room. I know that it’s crazy, but after I’ve selected a cadaver, I bring its plastic bag of heart and lungs back to my usual seat beside Eve. I cannot concentrate; it is too quiet. I switch on the small radio in the middle of the room which I realize must be there for just such occasions, but I find that my mind, distracted, floats away with the lyrics. I turn the radio off and start to talk to myself about the structures I’m looking for—“So the left coronary artery should be around here, and the circumflex branch should come off of it”—but I feel ridiculous, nervously speaking aloud in a room full of corpses. Before too long it’s just too creepy. I tie the bag and replace it, turn off the lights, and head home.

I learn that I am in good company when Dr. Goslow tells me that before he began teaching medical students, he didn’t feel as though he had “really ‘learned’ human anatomy with any confidence or done extensive dissections.” As a result, he says, “I lived in the dissection labs for three years. I would dissect into the night, six nights a week, until two or three in the morning. I recall more than once while dissecting alone in the labs that I was freaking myself out for no apparent reason.” In order to dissect, we detach from what we are doing, and that detachment is easier to accomplish in a crowd.

For us, in comparison to medical students of centuries past—who dissected unpreserved bodies in various states of decomposition—feeling uneasy in our lab seems foolish. Our cadavers are not only completely formalin-embalmed, but thanks to Arnis Abols, the lab manager who maintains the cadavers—and who for many years used to embalm and preserve them—they are then scrubbed with soap and water. Their hair is cut. Vaseline is rubbed into their hands, feet, and faces. They are covered with fabric drapes soaked in wetting solution. And though they may be stored for some time before they are brought up to the anatomy lab, Arnis changes any soiled drapes and washes the bodies again when they are ready for our use. As is true in our modern funerary customs, we are spared many of the body’s unpleasantries, and the elaborate preparation of our bodies enables us to separate from the totality of death more easily.

Yet despite the chemical smell and the distance from the decay of the dead, there are still moments when I am struck by the gravity and the lunacy of dissecting a human body. Andrew, my three-year-old nephew, is getting ready to begin preschool, and to quell his nervousness my brother and sister-in-law tell him that I go to school, too. “What do you do at school, Aunt Beanie?” he asks me over the phone before his first day. “Books!” I blurt out. “I get to read lots of books with pictures in them, and you will, too.”

Our cadavers are in our lab because they have explicitly chosen to be. Not only has each of them signed a declaration in life that they would like to donate their bodies to medicine, but in our case they have specifically designated that they would like their bodies to be donated to our medical school. Regardless of any of our misgivings, they knew what they were signing up for. However, this has certainly not been true historically, and it is not universally true for medical students even today.

During a pathology elective after my third year in medical school, I spoke with two pathologists, one from Iraq and one from Nigeria, about the sources of their first-year anatomy cadavers. Ade, the Nigerian doctor, described almost exactly the population that might have been found in an American or European anatomy lab decades ago. The dissected cadavers in Nigeria, he said, were all either “homeless,” and therefore “unclaimed,” or “criminals.” He laughed uneasily when he mentioned the criminals, and when I asked him why, he told me that he perceives the government in Nigeria to be incredibly corrupt. Friends arrived home from abroad with money for their families, only to be arrested on fabricated charges and made to pay outrageous fines on the spot to the arresting officers. “So, you see,” he said, “the definition of ‘criminal’ is a little too loose.”

Recent papers in the medical literature confirm that Nigerian anatomy departments do not dissect donated or “willed” bodies but instead have access only to executed criminals and the abandoned, indigent dead. In such an arrangement, one paper concludes, “the ethical considerations that attach to unclaimed and bequeathed bodies…have implications for the way human material is treated in the dissecting room.”

One of the coping strategies most often used by students in the anatomy lab is rationalization, and many of the students quoted in the papers offer arguments that I have either made, or heard from my classmates. “The knowledge to be gained is important for my career,” one student says; “[dissection] is an integral part of anatomy in which I must succeed to become a doctor.” Another student claims a more altruistic motivation: “I felt it was an activity necessary for the prevention of deaths in the future.” Yet another student absolves himself of responsibility by reminding himself that “it is not our making that these people are dead.”

And yet the provenance of the cadavers allows rationalization to take on a sinister and vindictive tone. Despite Ade’s argument that the definition of criminal was “a little too loose,” one Nigerian student took solace in “knowing that the cadavers could not have been good people when they were alive.” Another (with the telling use of the words “must have,” subconsciously acknowledging less certainty than their absence would) classified the cadavers as “criminals who must have unleashed terror on society and had been abandoned by their relatives.” Most hauntingly—and in a way that indicates a deep failure to view dissection as anything but harmful mutilation—one last student asserts that “I considered the cadavers to have been robbers and criminals who deserved no pity.”

The Iraqi pathologist, Sam, told me that none of the corpses in his medical school were native Iraqis, but rather that all the bodies appeared to be of Southeast Asian ethnicity. “I have no idea who they were or where they came from,” he said. “Maybe Vietnam or Cambodia? But they definitely weren’t Middle Eastern.” A recent journal paper examining dissection in the Middle East confirms, “A variety of sources have been used to acquire cadavers for medical training ranging from executed convicts to unclaimed or abandoned bodies from public/mental institutions, and also importing cadavers.”

A very different model of human dissection occurs in Thailand. The majority of the Thai people are Buddhist, and, due to their belief in reincarnation, there is a cultural reluctance even to donating organs for transplantation. Nonetheless, Thai medical schools benefit from cadavers that are, without exception, voluntarily donated. A recent paper from the British Medical Journal explains that the Thai culture deeply respects teachers “to an extent unfamiliar to Westerners,” and every Thai donor is granted the highly esteemed status of ajarn yai, meaning “great teacher.” Two ceremonies establish the status of ajarn yai: a dedication ceremony that occurs prior to dissection and a cremation ceremony that occurs at the course’s end.

In the dedication ceremony, Buddhist monks and family members of the deceased join students and faculty members in the dissecting room to chant and pray. The names of the donors are read aloud as the title of ajarn is conferred, and each cadaver is presented a bouquet of flowers. In a symbolic act of giving to the deceased, meals and gifts are then bestowed upon the monks.

Thai medical students are described as entering into a relationship with their ajarn yai that is in the familiar teacher-student model they have known since they were young. The students always refer to the bodies as “great teacher,” and never as sop, the Thai word for “cadaver.” They sometimes bring flowers to the bodies, greet them with traditional bows, and pray for their ajarn yai at the temples. In contrast to the American tendency to depersonalize the cadavers with anonymity, covered hands and faces, humor, even rationalization regarding the inanimate nature of the bodies, anatomy classes in Thailand post on each dissecting table the name, age, and cause of death of each donor. Students are expected to know the name of their donor when asked and to retain memory of the name as they practice medicine.

This intimacy yields situations that would be unheard of in Western medical schools. For instance, at the Dalhousie University Faculty of Medicine in Nova Scotia, an introduction is given prior to beginning dissection advising students to notify the faculty if they either know of a recent donor or have recently experienced the death of someone close to them. Any potentially known donor is removed, and, in the case of a recent death, the faculty ensures that the student dissect a body of different sex and age than the deceased relative or friend. In contrast, the Journal paper recounts that the grandfather of one Thai medical student had specifically requested that she dissect his body after he died. “She did so,” the paper reads, “and was thought to have especially good support from his spirit thereafter.”

For each of the donors and the medical students in Thailand, the semester culminates in a ritual procession. Buddhist monks lead the students, who carry the bodies of their dissected teachers to the crematorium. Buddhism itself may help establish this emotional closeness of students with their deceased teachers. Rather than think of themselves, the way a Nigerian student might, as distinct from the bodies they dissect, students in a Buddhist culture may be encouraged to contemplate the fact that their own bodies will eventually be no different from their cadavers.

The Buddhist sutra The Foundation of Mindfulness has in it a section entitled The Nine Cemetery Contemplations in which Buddhist monks are urged to view their own bodies on an inevitable continuum that ends with an unprettied vision of decomposition. “And further,” reads an English translation of one of the contemplations, “if a monk sees a body thrown into the charnel ground, and reduced to a skeleton, blood-besmeared and without flesh, held together by tendons,…he then applies this perception to his own body thus: ‘Verily, also my own body is of the same nature; such it will become and will not escape it.’” The Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh refers to this sutra as the “meditation on the corpse” and suggests that even lay followers of meditation and mindfulness

meditate on the decomposition of the body, how the body bloats and turns violet, how it is eaten by worms until only bits of blood and flesh still cling to the bones, meditate up to the point where only white bones remain, which in turn are slowly worn away and turn into dust. Meditate like that, knowing that your own body will undergo the same process. Meditate on the corpse until you are calm and at peace, until your mind and heart are light and tranquil and a smile appears on your face. Thus, by overcoming revulsion and fear, life will be seen as infinitely precious, every second of it worth living.

This type of vision is so entirely avoided by our culture, whose modern death rituals, if they even involve the corpse, center on a body embalmed and made up to prevent any whiff of decay. And so perhaps the question is not whether what is done to the body by doctors and anatomists is wrong but whether the way in which we regard the body—as a “great teacher,” as a criminal “who deserved no pity,” or as the eventuality of our own physical selves—can be ethically reconciled with the actions we perform upon them.

For me, in the anatomy lab, these questions linger, and their resolutions are outpaced and temporarily derailed by the revelations our forays into the body offer up. In this way, as in Renaissance Italy or Buddhist Thailand or Iraqi anatomy labs, the arguments against the discomfort of medical training are trumped by wonder and discovery.

At the end of our third week of dissection, we completely remove the skin from the upper arms of our cadaver, and I feel some sadness that she is beginning to look less human. Her purple-brown muscles are now exposed, and the skin on her hands and forearms has come to resemble formal gloves—like a Magritte painting where the only thing that belongs is so alone that it appears out of place.

On our course syllabus for the day, Dr. Goslow has written, “The Brachial Plexus—a nightmare in anatomy?” A complicated network of nerves, called the brachial plexus, stretches from the neck through the shoulder and the armpit, extending out toward the upper arm. It gives motion and sensation to the arm and hand. The cords of nerve begin in the base of the cervical spinal cord and the uppermost portion of the thoracic spinal cord. From those nerve roots, trunks of the brachial plexus (about the width of a piece of yarn, sometimes thicker) emerge, split, braid together, rejoin, split again, and around the underarm divide into the branches of the three main nerves of the arm: the musculocutaneous, the median, and the ulnar. The plexus is by far the most elaborate structure we have studied, and due to its placement, and the rigidity of our cadavers, it is hard to dissect out from the clavicle and underarm.

In the body, nerves look much cleaner than everything else; they seem less constitutionally affected by death. They are white and fibrous, and though we initially struggle to differentiate nerve from artery from vein, experience and texture begin to distinguish one from another.

Arteries are more muscular, as they must often regulate the level of resistance the blood encounters. If you whack your hand against the corner of a table, the arteries expand, or vasodilate, to increase blood flow to the injured area and promote healing—hence the swelling and redness that accompany a wound. To the contrary, if your body is in shock, or is hemorrhaging, the arteries vasoconstrict in an attempt to conserve blood for the brain and heart and other central organs by allowing less blood to flow into the periphery—hence the cold, sometimes blue pallor of a person in physiologic shock.

Veins are less sophisticated, to an extent, yet have a greater capacity to hold large supplies of blood and make it available to the circulation when necessary. It follows logically, then, that the texture of a vein would be less rigid than that of an artery. Think of how much more easily a thin-walled balloon is inflated than a thick-walled one, or how much more effort it takes to stretch a thick rubber band than a thin one. If one major function of the venous system is to distend and one major job of the arterial system is to constrict, then the relative consistencies of their walls make perfect sense.

Nerves, on the other hand, are wholly distinct. Instead of tubular, nerves are fibrous, like a bunch of threads bound together. The nerves feel like thin cords between my fingers, and they are strong. Whereas veins can sometimes accidentally tear away with an inadvertent tug, nerves tend to resist breaking. The trick is in finding them. They are mostly quite thin and often lie buried in fat or fascia. It can take an hour or more of picking fat away from an area the size of your cupped hand to expose one nerve you’re looking for. And part of the strangeness of dissection is not even knowing what lies beneath, not knowing wheat from chaff. Early in the semester, we run poor Dale ragged. “Is this something?” we ask at every turn. We don’t yet even know for sure vein from nerve from artery from webby fat. “Is this important?” As if there are things in the body that are of no significance whatsoever.

When we find the brachial plexus, we know it is important. Not only are these woven nerves responsible for all movement and sensation in our arms and hands, they are also a huge component of our fast-approaching exam, which is less than two weeks away.

Like the other lab groups, we have (as yet metaphorically) divided the body down the center so that one pair of students dissects the structures on the left side and the other pair performs the matching dissection on the right. The limbs are easily divided in this way, whereas the trunk and organ dissections are necessarily a group effort. Not surprisingly, Raj and I are happiest to be on opposite sides of the body, able to progress with our respective degrees of speed and care. Tripler, who shares the body’s left side with me, has begun to loathe time in the lab, however, and sees only lost efficacy in the group’s doing two dissections of the same structure.

“I don’t understand,” she says. “Can’t we all four just do one arm really well and then spend the time we’ve saved trying to learn all this stuff that still we haven’t had time to learn?” She is paging back through the lab manual; the structures we are supposed to learn are bold and in red print, and the pages are packed with them. “We haven’t even learned the coronary circulation yet.”

If we measure the learning process by the standards to which we’re accustomed from any other course we’ve ever taken, we should now be wrapping up new work in favor of reviewing the areas of the body we’ve already exposed. Instead we have two more full days of dissection before the exam, the first of three over the course of the term. In these two days, more than a hundred new muscles, arteries, and nerves will appear, all to be learned by name, function, beginning, and end point. Even certain empty spaces in the body have anatomical importance and their own names—the pulmonary fissure, for example, or the oblique sinus of the pericardial cavity. So the spot at which a muscle splits or the boundary of an organ dips is another landmark to memorize.

During lab, as Raj and I continue the group dissections, Trip and Tamara begin to construct vast charts with columns on the lab blackboards. We try to pool our knowledge and fill the chart without looking in our books and notes. Trip reads the columns to us, and Tamara chalks in the answers once we agree upon them. The board fills. Muscle: Palmaris longus, Proximal Attachment: Medial epicondyle of humerus, Distal Attachment: Distal half of flexor retinaculum and palmar aponeurosis, Innervation: Median n. (C7 and C8), Main Actions: Flexes hand and tightens palmar aponeurosis. And another line. And another. Over the course of the next few years, I will say many times to many people, “It’s not that med school is difficult conceptually, it’s just that there’s such an incredible amount of information to learn and attempt to retain.” There is no need yet for any kind of original thought. So far our learning is regurgitation at its most pure.

In Italy, amid the creative and scientific energy of the Renaissance, the public viewed anatomical exploration as a new and exciting frontier. However, in other parts of Europe, and in America, the reactions to dissecting cadavers were far less enthusiastic. Even today a natural trepidation exists when we think about bodies as subjects for dissection. Centuries—even decades—ago this unease was compounded by the fact that family members died at home. They were often prepared for burial by loved ones, and their dead bodies were central participants in the mourning process. In addition, widespread belief held that transition into the afterlife would be disrupted if the body could not easily be found in a marked grave. Therefore the absence of the corpse would at least interfere with long-standing funerary customs and important burial rites. At most it would disrupt the eternal fate of the parceled body’s soul.

As a result of these misgivings surrounding dissection, bodily donation prior to the 1940s was extremely rare. In the instances when donation did occur, bequests came largely from people who, like the men whose skulls were encased in glass in Padua, had directly observed the need for cadavers for teaching. One entertaining exception is the case of a nineteenth-century British captain who had been denied a war pension. In the hopes of shaming those who had refused him payment, the captain announced his decision to donate his body in the London Times, citing an interesting war wound.

The difficulty of acquiring adequate numbers of cadavers—from the time of Vesalius to modern-day anatomy labs in Nigeria and Iraq—has given rise to a constant and ongoing drive to find a substitute for the dead human body. Today three-dimensional digital images are made from living and dead bodies, improvements over the wax sculptures that were used for teaching in the eighteenth century. One collection of such wax sculptures is on display today in Bologna, Italy, which I visited after my stop in Padua. The collection is open to the public but unlikely to be found by tourists—it is housed on an upper floor of a college building in Bologna’s Palazzo Poggi, accessed by climbing several unconnected staircases and walking through corridors filled with glass cases of bird skeletons and fish bones.

A marble dissecting table occupies the center of the first room of the palazzo’s Anatomical Museum. Along the walls, in glass cases and positioned on pedestals two skeletons stand: a male, holding a staff, and a female, holding a scythe. Their serious props and poses make them look ridiculous. Between the two skeletons, four male wax figures stand in various stages of dissection. Ercole Lelli, the sculptor of the full-body models in the Palazzo Poggi collection, was commissioned to make these models for the University of Bologna by Pope Lambertini in an eighteenth-century attempt by the Catholic Church to dissuade cadaveric dissection.

The irony here, of course, is that despite the intended appearance of the removal of subsequent layers of skin and muscle, the sculptures have never had any such layers. The first appears as if he has been skinned. On the second, the superficial muscles have been “removed” to expose the muscles that lie beneath them. The third is still further dissected, and the fourth displays an empty abdomen, revealing the musculature of the abdominal and pelvic floors. The jaw has now fallen off; with the skull stripped bare, there is no tissue to attach the mandible to it. The waxen upper teeth arch over empty air. The figure resembles Edvard Munch’s Scream—only a chasm where bone should be.

Interspersed among the pedestaled figures are a hodgepodge of random anatomical constructions of wax and bone. One glass case contains the perineal muscles, which would lie in between the anus and the scrotum or vagina, displayed alongside a model diaphragm and wax muscles of the hands. In another case, which recalls the relics of St. Anthony, the muscles of the pharynx, larynx, and neck are displayed. Thin straps of muscle are splayed out around the thyroid cartilage so that from afar the case looks as if it contains a pinned-down specimen of rare beetle. Near the window is a glass dome that looks like an African violet globe or a cake plate. In it are a solitary sternum and four ribs.

The second room is more ghoulish. The figures in it were sculpted in the mid-1700s by a sort of wax-anatomy team, Anna Morandi and Giovanni Manzolini. It is hard to pinpoint the difference in these sculptures versus those by Ercole Lelli, other than to say that there is emotion in them, a kind of pathos. Several of the works incorporate waxen elements of the recognizably human, which many similar sculptures do not bother with: skin and hair, an intact ear, a seductive posture, a drape of clothing. As in the anatomy lab, when painted fingernails or faces are unveiled, the closer a body seems to life—even in wax—the more disturbing it becomes.

The bones of the skull lie on a navy cloak, alongside a lone open mouth, a severed tongue. The fabric somehow shifts these sculptures not only from clinical to artistic, but also from toneless to emotive. The effect is disarming, in part because of this humanization, and in part because this particular shift away from the scientific introduces a whiff of sensational voyeurism. An open chest cavity is shown, but with intact shoulders and a gracefully upturned neck and chin, just exposing a lovely jawline before a red wax cloth shrouds the implied shape of an absent head, severed from the body at the mouth.

A darkened alcove lies at the end of this room in which the waxen body of a beautiful young woman lies alone. Her head lolls back over the edge of a velvet pillow, exposing her fair throat and the string of gold beads that encircles it. From her neck to the top of her pubic hair, she has been cut open, exposing her opened heart, her great vessels, her diaphragm, liver, gallbladder, kidneys, a stump of sigmoid colon, and also an opened womb, complete with a small, tucked fetus inside. Her eviscerated organs lie at her feet—lungs, omentum, stomach, intestines—and beside her lies a semicircle of the pink-hued flesh of her breasts and abdomen, as if a large puzzle piece or lid were lifted from her living body, neatly revealing her interior. The viewer feels voyeuristic, implicated in a glance that might be akin to that of a serial killer.

As I leave the museum, I spot two glass cases that look like the fortune-telling Gypsy mannequins at an antique arcade. In fact they are waxen busts of the sculpting duo, both done by Anna Morandi. Giovanni Manzolini is depicted as serious, holding an opened heart in his hands. Morandi, on the other hand, has sculpted her self-portrait with a hint of a coy smile. Her hands peel the scalp off of a decapitated head, exposing a bit of brain.

Lifelike as they are, the waxen figures are no more than a three-dimensional textbook—accurate, but completely unable to offer the propelling moments of revelation and functional comprehension of actual dissection. The body is staggeringly complex, and to understand it with any degree of completeness demands dealing with the thing itself—picking up and holding the heart, tracing the path of an artery by threading a pipe cleaner through its lumen. Experienced surgeons return to cadavers constantly throughout their careers, to learn new procedures or practice difficult techniques. The true body as a teaching tool is neither inexpensive nor reusable, but it grants moments of instant and penetrating education: semilunar valves flaring wide and joining with their soft catch of water.

As anatomical exploration across Europe and America began to flourish, the public became more and more fearful of a medical institution that seemed to feed on corpses. Anatomists were not discriminating when it came to the source of their cadavers, and the public started to worry that practically anyone was susceptible to being taken to the medical college and dismembered after death. These fears multiplied when combined with centuries-old rumors that anatomists and surgeons routinely performed vivisections—dissections of the living. Few actual references to such a practice exist, although the Anatomia Magistri Nicolai Physici, a manuscript of the court physician in Baghdad at the end of the tenth century, states flatly:

The anatomists went to the authorities and claimed prisoners condemned to death; they tied their hands and feet, and made incisions first in the animal or major principal members, in order to understand fully the arrangement of the pia mater and dura mater, and how the nerves arise therefrom. Next they made incisions in the spiritual members in order to learn how the heart is arranged and how the nerves, veins, and arteries are interwoven. Afterward they examined the nutrient organs and finally the genitalia or subordinate principal members. This was the method practised upon living bodies.

Though any acknowledgment of historical vivisection was, and still is, fiercely contested, versions of such gruesome accounts persisted and inspired intense public fear and mistrust of the medical field.

Rumors of vivisection aside, whether it is in fact wrong to dissect the human body is neither a purely historical nor a simple question. Over the course of the semester—indeed over the course of our years of medical training—my peers and I would frequently bump up against feelings that we were doing something innately wrong.

As I sit with Eve, my fingers threaded through the nerves of her brachial plexus, following each branch as it joins with and splits from others, becoming renamed at each intersection—radial, ulnar, musculocutaneous—I wonder how I would feel about her had she been a murderess. I know there would be a palpable difference. And had she been impoverished? A ward of the state? A body unclaimed by friends or relatives? A foreigner whose country I did not even know? I wish I could say that those circumstances would make no difference to me, that I would view her just as I do now. I suspect it is not true. The emotional connection that I feel to Eve is due in part to my ability to have sympathy for her lifelessness. In spite of my misgivings about capital punishment, this sympathy would be less readily evoked in me if she were someone whose death was the result of her having killed another.

Eve’s body resonates more profoundly with me because I know that she is on the stainless-steel table of her own choosing, and yet that simple decision allows me to make her into the type of person I imagine would choose such a thing: educated, opinionated, concerned with the greater good, unsentimental, rational. Of course, the reality is that some of these things could be true of Eve, or all of them could, or none. But Eve’s own agency in her dissection more easily allows me to assign her the traits I imagine a woman of her age would need in order to decide to donate her body to this kind of fate. The fact that the decision was hers, and that it is a special kind of decision that requires a sort of chutzpah, makes it easier for me to think of her as someone like my grandmother. It makes it easier to think of her as someone not so different from the way I see myself.