chapter six

In Pursuit of Wonder

CREON: About Polyneices:

He is forbidden

Any ceremonial whatsoever.

No keening, no interment, no observance

Of any of the rites. Hereby he is adjudged

A carcass for the dogs and birds to feed on.

And nobody, let it be understood,

Nobody is to treat him otherwise

Than as the obscenity he was and is….

ANTIGONE: Religion dictates the burial of the dead.

CREON: Dictates the same for loyal and disloyal?

ANTIGONE: Who knows what loyalty is in the underworld?

SOPHOCLES, ANTIGONE

Once we have finished the upper-arm dissection, we move down the limb to the forearm and the hand. We are a full month into the semester. Raj and I both begin working on the palm dissection, which is difficult in part because the hand feels very human. In order to remove the skin from the hand, we must, by necessity, hold the hand in ours, an intimate and familiar gesture that makes the directive to take a blade to the skin all the more unsettling.

As I cut the palm, I often feel the way one does when you hear about an accident or a gruesome wound. It is as if someone recounted an injury: The blade went right through her palm—took off the skin. You would turn your head to the side and wince, suck air through your clenched teeth, identifying with the pain. Because I can call up the feeling of an inadvertent glance of a kitchen knife on the hand much more readily than any cut across the abdomen—and surely because the palm dissection itself requires great pressure and pull—it is an emotionally tiring chore.

The palm dissection is also difficult because the skin of the palm is so much tougher than any other we have encountered. Usually one or two scalpel blades per person last the full seven hours of lab. On the palm alone, I go through five. In lecture, Dale has read us a passage written by Libbie Henrietta Hyman, a 1920s anatomist:

Dissection does not consist of cutting an animal to pieces. Dissection consists in separating the parts of an animal so that they are more clearly visible, leaving the parts as intact as practicable.

In dissecting an animal, very little cutting is required. Cleaning away the connective tissue which binds together and conceals structures is the chief process in dissection. In doing this, use blunt instruments, as the probe, forceps, or fingers. Avoid the use of the scalpel and scissors. You will probably cut something you will need later on. In short, do not cut; separate the parts.

When he has finished reading, he raises his head and says, “That’s a warning about your hands. Don’t let them look like a weed whacker has been through them.”

His voice hangs over us as our patience wears thin. Beneath the skin of the palm is a thick, fibrous sheath, a kind of broad, flat tendon, called an aponeurosis. In lab, Tamara reads us the relevant instructions from the Dissector: “Carefully remove the palmar aponeurosis. Do not damage underlying vessels and nerves.” Three hours into taking turns dissecting, Tripler and I are ready to hurl the Dissector against the wall.

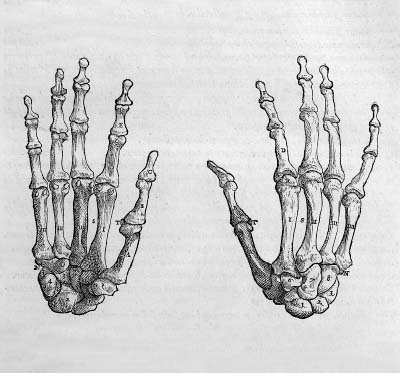

We take breaks from the tedium to work on uncovering the structures of the forearm. Between the muscles of the hand and those of the wrist and lower arm, we are awash in Latin: Flexor pollicis longus and brevis, Flexor digitorum profundus and superficialis, Adductor pollicis, Extensor carpi ulnaris. We will learn ten thousand new words in the first year of medical school.

By the end of the day, Trip and I are making dumb jokes that we find hilarious. Dale comes by to check on our progress and offer encouragement, and we tell him we have dubbed the day “nightmarus longus.” We think it is the funniest thing we have ever heard.

After the initial frustration of the palm dissection, the following day is completely different. Crazy clarity and order start to arise out of the fat of the palm. Muscles and nerves and arteries are all tangled around each other at first blush, but then, as fat is cleared away, a kind of layout takes shape, along with a larger context.

Two main arteries—the radial and ulnar—provide a supply of oxygenated blood to the hand. The ulnar artery feeds into an arterial arch in the palm, the superficial palmar arch. It looks a little like a traffic roundabout, with branches breaking off a central curve to run up each finger. As we clear away the fascia, we can slide a finger beneath this arch to appreciate its detail. The radial artery meets a similar end at a deeper level, diving beneath the ulnar roundabout to form the deep palmar arch. If you look at the palm of your own hand, there are two main skin creases that cut across it, side to side—a palm reader would designate one as the love line. The crease closest to the base of your fingers is positioned about where the superficial palmar arch lies. About an inch below the lower crease is the region of the deep palmar arch.

The intersection of these two arches and their subsequent shared pathways—and other intersections like them elsewhere in the body—has a beautiful name: anastomosis. The verb form is even prettier—the arches anastomose (from the Greek word meaning to intercommunicate, inosculate; said of blood vessels, sap vessels, rivers, and branches of trees). It is fitting, then, that anastomoses have highly important functionality. They represent multiple possible pathways for blood, so that in case of the interruption of one vessel, as with blood clots, trauma, or atherosclerotic narrowing, the blood’s flow in areas of particular importance will be preserved. Not surprisingly, the body’s most prominent anastomosis is the circle of Willis, joining the two carotid arteries with the basilar artery to provide blood to the brain.

As if to prove that the body sequesters resources, there is still more fat in the palm of our thin cadaver. We work to clean it away, and beneath the superficial palmar arch are slick, shiny white tendons leading to each finger, seemingly from the center of the palm. As we continue to separate out structures from fascia, we realize that for the most part the tendons actually originate in the wrist and forearm and first slide beneath a fibrous band at the wrist (through the famous carpal tunnel) and then again at the base of the palm, beneath the fibrous flexor retinaculum. We discover similar tendons running into each finger on the back side of the hand, coming from the wrist and the back of the forearm.

The sheen of the tendons renders them almost luminous. They look exactly like those in raw chicken—another in a long line of unfortunate links all too easily made between dissection and cooking. They also provide another powerful illustration of anatomic form relating to function. We do not discover this, though, until we ask Dale to come by and help us bring order to the twenty-odd muscles in the forearm alone. Dale reminds us that tendons originate at the end of a muscle and, by definition, connect that muscle to bone. Therefore, since a muscle shortens when it contracts, a tendon necessarily will pull on the muscle and thus tug on the bone in its contracted state.

Dale takes the upturned palm of our cadaver in his hand. “There are two opposing groups of muscles in the forearm,” he explains, “the flexors and the extensors. The extensors are on the top of the forearm, and they extend the wrist like this,” and here Dale bends back his own hands and splays his fingers as if he is stopping traffic. “The muscles on the underside of the forearm are the flexors,” he continues. “They perform the opposite motion,” and he snaps his hands down at the wrists and curls his fingers into a fist. “Extension,” he stretches his wrists and fingers wide, “and flexion,” he curls everything in.

Going back to the cadaver’s arm, Dale says, “This makes sense, right? Because if you pull on any one of these tendons going from a muscle on the underside of the forearm to the fingers or the hand, everything bends back toward the spot on which you are tugging.” He lifts two different sinewy tendons from Eve’s forearm and pulls gently on one and then the other; the cadaver’s wrist flexes. “Flexor carpi radialis and Flexor carpi ulnaris,” he says. One wrist flexor on the radial side and one on the ulnar side. Flexor for their actions, radialis and ulnaris for their locations, and carpi for the fact that they attach to the carpal bones of the wrist.

“Let’s see if you have a palmaris longus,” Dale suggests, and bends my hands back as all three of us look at the inside of my wrists. “Oh, yeah, a really clear one,” he says, and he is right. Through my skin, and beneath a few blue traces of vein, we can see a tendon about the width of a shoelace that runs right up the middle of my wrist. “Watch this,” he says, and presses hard with his thumb on the tendon, about two inches back from the base of my palm. My fingers curl in. “Not everyone has that tendon, and we don’t know why,” Dale notes. And then he continues, while I am still staring at the action my body has performed through no will of my own.

He lifts two other tendons in the forearms of our cadaver, and her fingers bend inward even more severely than mine did, as if she is grasping something. “Flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus,” says Dale. Digitorum for the fingers, superficialis and profundus for their respective locations at the surface and in the depths of the forearm musculature. “And here, flexor pollicis longus.” He tugs, and the thumb comes toward the wrist in a solitary movement. The tendons make a marionette of the skeleton; even in death the bones have no choice but to respond to the strings that pull them.

Once Dale has finished his tour of the muscles, he stands beside our cadaver, as Trip and I retrace the map he has made for us so that he is satisfied that it has sunk in. It has, and we feel relief and some astonishment that order can be superimposed on chaos so quickly by someone who knows the terrain well.

We feel triumphant. In contrast to the endless charts and lists we were compulsively committing to memory, we now understand what it feels like to grasp the function of anatomy.

This moment helps me appreciate Vesalius’s commitment to firsthand study of bodies at all costs. As his anatomical discoveries resulting from direct bodily exploration began to resonate throughout the medical world, the authority of Galen’s texts slowly eroded. One by one, anatomists aligned themselves with the Vesalian dedication to human dissection, and a profound shift in the foundation of medical education resulted.

Staring from my own curled fingers to those of the dead woman on our steel table, I feel a rush of excitement, a new thrill of definitive understanding. I begin to imagine the energy, the promise that infused young doctors and anatomists when Vesalius’s revolutionary ideas began to take hold. Galen’s long-inviolable reign of twelve centuries was being toppled by the lowly body, the corporeal, the dead. Yet this burgeoning excitement in no way spread to the populace at large. Who on earth would offer their bodies to such an end?

In the absence of bequests, sixteenth-century surgeons and anatomists began to profit from frequent executions, laying claim to the bodies of criminals. Because the bodies were those of convicted transgressors, their families were in no position to make claims to the right of proper burial. The bodies were taken directly from the scaffold to the anatomical theater, often by surgeons and anatomists themselves, who would come to be seen as the hangman’s vultures. Records tell of anatomical theaters and gallows standing adjacent to one another, so that transport could be swift and unimpeded.

Executed bodies were especially prized because of their very recent good health. As opposed to the bodies of people who had died from illness or injury, those of executed criminals were more likely to have been healthy, and they therefore had normal anatomy from which to learn.

In the 1700s the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland was one of the many sites of anatomical teaching across Europe that benefited from the “subjects” offered by the gallows. However, as a history of the college points out, such an arrangement was not fully satisfactory. For one thing, eighteenth-century students had begun doing their own dissections, and, unlike the cadavers in modern labs, these bodies were not in any way preserved. Thus, instead of two or three cadavers per year supplying an entire cohort of future physicians, two or three cadavers per year now supplied just one anatomy student. Hence, “the demand for subjects greatly exceeded the number made available by the courts of justice.” Moreover, the college felt the brunt of the public’s disdain, and discretion helped only to a certain degree:

…The founders of the College school thought it necessary to provide a rear entrance…. The publicity attached to the arrival of a criminal’s body was not welcomed by anatomical schools. The outraged feelings of the relatives and friends of the murderer, whose dissection was for them an intolerable indignity, on some occasions led to riot….

Great Britain was one of the first countries to establish anatomical laws, which would inspire similar legislation across Europe and in colonial America. The combination of a growing scientific demand for cadavers and widespread public distress regarding anatomical dissection presented an unusual opportunity for the British government.

In the eighteenth century, sentences for crimes in Britain were severe, and death sentences for relatively minor offenses such as thievery were not uncommon. As the practice of dissecting the numerous victims of hanging went on unofficially for some time, the British government began to recognize that endorsing such a process as official law could have its benefits. Sanctioning the dissection of certain criminals following death would fill two societal needs: Surgeons and anatomists would be supplied with the cadavers to fill the increasing educational and scientific demand, and a judicial sentence even more terrifying than the death penalty could be wielded. The condemnation carried the weighty implication of eternal penance—a sentence not only to end this life but to bring suffering, or at least lack of restful peace, to the life that followed. Hence the 1752 Murder Act was passed, instituting the punishment of “penal dissection” following execution for anyone who was convicted of murder.

Tracing the motivations for and specifications of the Murder Act of 1752 in his wonderful exploration of Renaissance dissection, The Body Emblazoned, the scholar Jonathan Sawday writes:

What was needed, it was felt, was a punishment so draconian, so appalling, that potential criminals would be terrified at the fate which awaited them in the event of their detection…. Some new horror was called for which would thwart delinquent desires on the part of the unruly metropolitan populace…

Yet although the Murder Act did establish a steady supply of bodies to anatomy theaters, it had the negative effect of reinforcing the public’s deep-seated aversion to dissection and an ever greater mistrust of anatomists.

Even with murderers designated for dissection, anatomists still turned to other sources for bodies when the supply from the gallows proved inadequate. Just as for the students of Vesalius, the only alternative source was grave robbery. Across Europe the increasing demand for cadavers gave rise to an entirely new profession: the resurrectionist.

In both Europe and America, profits were to be made for those who could “resurrect” dead bodies from the graveyard and deliver them to the medical colleges. Resurrectioning was an unsavory profession, to be sure, and one that, once its existence was discovered, outraged the public.

Compared to the corpses of executed criminals, bodies that were unearthed were undoubtedly in far worse condition. In all likelihood, mourning proceedings had gone on for several days following the death, so the body would have had as many days to decompose, unlike bodies brought directly from the gallows. Furthermore, the resurrected bodies would have been buried for a variable length of time, adding to the degree of decay. Bodies of the very poor, buried coffinless in mass graves, were often the easiest to disinter. However, they would also have been more exposed to the earth and thus in a more advanced state of rot.

Though “fresh” remains brought the resurrectionist more money, the need of the colleges was great enough to ensure that a use would be found for any subject. In the interest of fetching top dollar, special techniques and tools were developed for exhuming bodies as quickly as possible. Rather than waste the time and energy required to unearth the entire length of the coffin, adept resurrectionists would remove the soil only above the head. A special lever would then be slid beneath the coffin’s lid and lifted, to break the lid and create an opening through which the body could be dragged. Next, all clothing was removed from the body and replaced in the coffin. This step was imperative because, ironically, theft of a body would result only in the charge of a misdemeanor, but robbing material goods from a grave was a felony, for which an offender could be hanged.

Many anatomists and medical students could not afford the cost of a “professionally” obtained body and instead resorted to grave robbery themselves. Some medical colleges would even accept all or a portion of a student’s tuition in the form of cadavers. Porters in the anatomical theaters were also encouraged to supply bodies and were paid over and above their standard wages to do so. Students and teaching demonstrators would also often supervise the efforts of the resurrectionists. An 1814 letter in the archives of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland outlined the requirements for a demonstratorship position. The letter underscored the fact that the professor hired would be expected to “undertake the direction of the resurrection parties.”

As more and more graves were disrupted, public outrage increased. The fear of dissection now seized the public psyche. Editorials were written to papers, lawsuits were filed, leaflets were distributed. Expensive, tamperproof coffins were designed, made of metal rather than wood, with spring catches inside to prevent the lid from being pried off; iron vaults were sunk into the ground, and coffins were entombed within them. Some wealthy families even paid armed watchmen to guard their grave sites.

The graves of the poor were inevitably more vulnerable. Poor families took to marking grave sites with flowers or stones or shells, so that any disturbance would be detectable. In a more preventive measure, nineteenth-century African American communities, whose graveyards were disproportionately violated, often mixed the topsoil used to cover the coffins with straw and grasses, in an attempt to make the resurrectionist’s spade catch and fail.

In rural Ireland, where graveyards were often set apart from the watchful eyes of town residents, resurrectionists executed less care in their trade, leaving graves open, damaging tombstones and monuments. Cadavers were sometimes even left on the side of the road if the grave robbers feared being caught in the act. Armed relatives of the deceased would often spend every night guarding their family graves until the corpse would have decomposed enough to render it useless—a time period that varied greatly depending on the season. Undeterred, groups of grave robbers began to carry weapons, and battles actually took place among tombstones. Towers were built in which weapons and ammunition were stored, so that relatives could stand watch over the graves from on high.

There are few recorded instances of members of the upper class and policy makers taking up for the poor by protesting the practice of grave robbery. In general such attempts were met with disdain. In the archives of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, the records of such a case can be found. In 1819 in Dublin, an Irish charitable organization proposed funding a watch over one of the city’s graveyards for the poor. Professor James Macartney of Trinity College’s anatomy department swiftly responded, railing against the proposal by appealing to the pocketbooks and lifestyles of the Dublin middle and upper classes. He pointed out that such a watch would harm the financial well-being of the city, since the medical school brought seventy thousand pounds per year to Dublin. Further, he noted, “I do not think the upper and middle classes have understood the effects of their own conduct when they take part in impeding the process of dissection.” Specifically citing the practice of the day of using cadaveric teeth to build dentures for the wealthier classes, Macartney added that “very many of the upper ranks carry in their mouths teeth which have been buried in the hospital fields.”

Governmental intercession was, however, sometimes a necessity. In Dublin this occurred when dissected human remains were once found floating in the river Liffey. A nineteenth-century county councilman’s letter gently mentions this “unsavoury finding” and asks the medical colleges to take greater care in disposing of their used “subjects” in the future.

Anatomists and resurrectionists did not work alone. In addition to employees of the medical school, others with access to dead bodies benefited from the trade. Accounts abound of graveyard watchmen paid to ignore bands of resurrectionists. Undertakers sometimes also played a role, making funerary arrangements with family members and then accepting fees from anatomists to send the bodies to medical colleges instead. Coffins would be filled with sacks of dirt of the body’s weight. And, as Professor Macartney pointed out, sometimes cadavers’ teeth were removed and sold, as well as their gold fillings.

As communities grew more vigilant in watching over their burial grounds and fending off body snatchers, the demand for bodies nonetheless continued to grow. As a result the resurrection trade became an import-export trade, with cities like Dublin, nearer to rural areas, shipping bodies across the sea to London.

It’s not difficult to conjure the unpleasantries that must have been associated with the transportation of decomposing bodies over long distances in a ship’s unrefrigerated cargo hold. The inevitable shipping errors also occurred, sending packages of dry goods and foodstuffs to medical colleges and thus presumably delivering the intended cadavers to unfortunate, unsuspecting recipients.

Continued anatomical exploration and discovery fueled the commitment to dissection in Britain, as elsewhere, but the cultural discomfort with such a trend was unabated. By the nineteenth century, it was clear to the British government that the number of cadavers supplied to medical schools by the 1752 Murder Act was insufficient. In addition, the means by which resurrectionists were compensating for the inadequate number of corpses was causing civic unrest. Not only did the routine disruption of graves continue, but eventually—perhaps inevitably, with the least decomposed bodies providing the highest profits for resurrectionists—dead bodies began to arrive at medical schools in “suspiciously fresh” conditions.

The best-known example of this is that of the infamous nineteenth-century Edinburgh duo William Burke and William Hare. The two Irish immigrants to Scotland did not begin their shady dealings as body snatchers but came upon their trade almost by accident. Hare’s wife ran a cheap boardinghouse. When an elderly lodger named Donald died without having paid his past bills, Burke and Hare decided to make up for the loss by selling the old man’s body, which, having never been buried, was in comparatively pristine condition. The substantial profit they made off the cadaver, and the ease with which they had acquired it, proved to be more temptation than the two men could withstand. When a second boarder, a miller named Joseph, fell ill, Burke and Hare did not wait patiently for his demise but instead plied the sick man with large amounts of whiskey and then smothered him to death. When that body yielded the pair with a similar amount of money—and a surprising lack of suspicion—their destinies were sealed.

Before the new livelihoods of Burke and Hare were to be discovered, twelve women, two men, and two handicapped children would be murdered and sold to anatomists. Many beggars and street peddlers were among the victims, as well as Joseph, a prostitute and her retarded daughter, and William Burke’s cousin through common-law marriage. One youth, known as “Daft Jamie,” was a familiar street character in Edinburgh whose absence was noticed. In order to render his body less identifiable, Burke and Hare severed the head and deformed feet from Jamie’s corpse. The murderers’ tactics were always the same: They preyed on the very poor, promising food and drink and shelter, and always chose someone they were sure to be able to physically overpower when the time came to do so.

Despite the practically still-warm condition in which Burke and Hare’s “subjects” arrived at the anatomy school—and the clear evidence of violence that must have been perceived by those who received the body of Daft Jamie—the pair’s undoing was ultimately a result not of suspicious anatomists but of neighborly mistrust. In 1828 a woman named Mary Docherty was begging for food and money in Edinburgh, having come there from Donegal, Ireland, to search for her missing son. Burke brought her home with the promise of a meal and invited her to a Halloween party following dinner, where, after she had drunk an appropriate amount, she was summarily smothered and hidden in the bedstraw until Burke and Hare could take her to the anatomy school. In the end Burke betrayed himself, and Hare betrayed him as well. When visitors arrived at Burke’s house the following morning, Burke acted strangely and demanded that no guest go near the bedstraw. Curiosity piqued, one eventually did, only to discover Mrs. Docherty’s body, now lifeless and cold. Given the chance to spare himself, Hare gave evidence that convicted Burke, who was hanged.

In the ultimate degree of irony the penal codes of 1828 Britain afforded, following his execution Burke was dissected at an event witnessed by select ticket holders. The report of the execution reads in part:

Early on Wednesday morning, the Town of Edinburgh was filled with an immense crowd of spectators, from all places of the surrounding country, to witness the execution of a Monster, whose crime stands unparalleled in the annals of Scotland…. As soon as the executioner proceeded to do his duty, the cries of “Burke him, Burke him, give him no rope,” and many others of a similar complexion, were vociferated in voices loud with indignation…. Burke’s body is to be dissected, and his Skeleton to be preserved, in order that posterity may keep in remembrance his atrocious crimes.

At the end of the dissection, two thousand students filed past the body, which was then exhibited to the general public and said to have been viewed by thirty to forty thousand onlookers. And even today, in the library of Edinburgh’s Royal College of Surgeons, a set of books can be seen whose bound covers were made from the skin of William Burke.

The Burke and Hare case received widespread attention, and the British public seized upon two facts: first, that anatomists in their thirst for subjects to dissect had fueled a market that would devise such a horrible scheme, and, second, that despite the fact that some of the bodies supplied by the murderers had blood crusted around the mouth, nose, or ears, no suspicion was ever reported by the medical school.

These sentiments only contributed to the prevailing mistrust of the medical community and gave rise to a kind of conspiracy theory when, by sheer chance, the arrests of Burke and Hare were followed closely by a cholera epidemic that swept through England. Doctors warned of the risks of contagion and insisted that the sick be quarantined in specific hospitals. The dead were rapidly buried in secluded graveyards. Yet these measures gave scant assurance to the citizenry. Instead the popular opinion was that patients—alive or dead—were not as unwell as the doctors had declared. The consensus was that the sick and dead were being taken in by doctors for experimentation and that all the regulations and recommendations surrounding the disease were a hoax to support anatomists’ endeavors.

The traits of cholera as a disease did little to refute these notions. In the throes of the illness, the body’s muscles can be gripped by contractions that, after death, suddenly release, giving the perception that some degree of life remains in the body. Similarly, in severe cholera, living patients might turn blue, breathe almost imperceptibly, and feel quite cold to the touch. Such patients might be deemed dead, only to later recover, multiplying fears of being buried alive or, worse, of being vivisected.

It was, in part, this climate of public furor over Burke and Hare, resurrectioning in general, and (however misguided) cholera, combined with pressure from the colleges to provide a greater number of cadavers, that pressed Parliament to look to a new population for a supply of bodies. Their solution was to pass the 1832 Anatomy Act.

Replacing the preexisting Murder Act, this new measure authorized officials to take possession of the bodies of dead paupers. The bodies of the poor would then be transported directly to the medical colleges for dissection. A punishment that had been assigned to the most severe of criminals was now the fate of those whose only crime was poverty.

The act was justified in two primary ways. First, it was cast by legislators as a means by which the poor could repay their indebtedness to the society that had sustained them. If paupers had been given room and board for “free” in homes and workhouses (the work perhaps overlooked as a sufficient form of repayment for food and lodging) and had been unable to pay for it during their lifetimes, then the use of their bodies was a natural—if rather abstract—way for them to negate the debt which had been incurred by their poverty.

Second, by specifying that the act benefited from “unclaimed” bodies, the argument could be made that if there was no one to claim and mourn over the body, then there were no living relations who would suffer from the knowledge that a loved one was being dissected. This was meant to draw a distinction between those thoroughly mourned and carefully buried dead who risked being unearthed and dissected, to the agony of their surviving family members, and those who had no friends and relatives to endure such knowledge. (Interestingly, this may have marked the beginning of a cultural shift in that the main threat of dissection was perceived to be to the feelings of the living, as opposed to the everlasting soul of the deceased.) In fact, the designation between claimed and unclaimed bodies was not altogether clear. It could be construed that a body that was not claimed for burial had no relatives or friends to mourn it. However, it was equally likely that it simply meant that there were no friends or relatives who had the means to pay for a burial, and so the body was left to be buried at the expense of the state.

Either way, medical schools profited from the expansion of sanctioned subjects from murderers alone to murderers and paupers. Certain colleges had more of an advantage than others. If a medical school was affiliated with—or even physically connected to—a hospital for the poor, then it had far easier access to the bodies of the recently deceased poor than did freestanding, unaffiliated schools. Even under such prime circumstances, the mathematics of required cadavers and available bodies did not always square. An 1829 commentary on a small, private medical school connected to one of Dublin’s large poorhouses calculated that

this large pauper asylum does not half supply this small private school, its proprietors being obliged to have recourse to the ordinary means of procuring dead bodies by exhumation…. There are…at present, in Dublin, upwards of five hundred dissecting pupils; allowing each of them the lowest quantity stated by those examined on the question, that is three subjects each, they would, of course, require 1,500, a number of unclaimed bodies which would, I think, not be supplied by all Dublin, not in one year, but even in ten.

As the commentary suggests, illegal acquisition of bodies continued, even under the Anatomy Act. Ploys to make illicit money from the anatomy trade were spurred on in part by the new legislation, which centered on the claimed versus the unclaimed dead. Though the resurrection trade was predominantly male, women would sometimes be employed to sit at the bedside of a dying stranger in a poorhouse, pretending to be a grief-stricken relative, or to circulate among hospital wards to learn which patients were gravely ill, so that they could show up following a death and have the body released to them. The valuable “fresh” bodies, which might otherwise have gone unclaimed and have been transported to the anatomy labs free of charge, were now sold to the schools from the entrepreneurs who had claimed them. The hospitals and poorhouses had little incentive to thoroughly check the credentials of those who claimed the bodies of the dead, for it meant their employees did not have to spend time arranging transport to the colleges.

Despite governmental intentions, public outrage—and mistrust—over anatomical dissection grew in response to the expansion of the cadaveric pool to include the poor, and to the fact that these legal measures had no effect on the vigor of the resurrection trade. Facts and rumors swirled together to incite an already-volatile climate. The head of a dead three-year-old child was discovered to have been removed from its body and replaced in the coffin with a brick. The head was eventually found in the local apothecary’s shop and duly sewn back onto the body. In Aberdeen local dogs unearthed human remains in the backyard of the anatomy school, provoking a riotous crowd to burn the school down. Two medical students were caught in Scotland attempting to steal a body from a grave and, though at first held in a private home, requested to be taken quickly to jail for their own safety. Once the grave-robbing students were imprisoned, hundreds of people surrounded the jail, holding axes above their heads and threatening to kill the offenders.

In his diary from this period, Charles Darwin recounts having seen an angry mob descend upon two resurrectionists in Cambridge: “Two bodysnatchers had been arrested, and whilst being taken to prison had been torn from the constable by a crowd of the roughest men, who dragged them by their legs along the muddy and stony road. They were covered from head to foot with mud, and their faces were bleeding either from having been kicked or from the stones.” With language that conflates the resurrectionists’ fate with the victims of their crimes, Darwin writes, “They looked like corpses, but the crowd was so dense that I got only a few momentary glimpses of the wretched creatures…. [Eventually] the two men were got into prison without being killed.”

The 1830s roiled with riots against various and ongoing defamations of the dead, both in America and abroad. The Massachusetts Anatomy Act was passed in 1831 and amended in 1834, similarly allowing unclaimed bodies to be claimed by medical schools. By 1913 the only states that had not passed a law designating the indigent poor for dissection were Alabama, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Tennessee—all southern states whose schools benefited from their large prison systems, which held predominantly African American populations.

For their part, physicians of this period felt betwixt and between. As anatomical knowledge and surgical advancement exploded, the public demanded that medical practitioners have a working knowledge of anatomy and yet continued to protest the cadaveric dissection by which this knowledge was obtained.

The medical information gleaned by anatomists and the resulting advances in treatment were too tantalizing to doctors and policy makers alike to threaten the continued availability of bodies for dissection. Medical understanding, then as now, ignites a thrill in the human spirit. The ability to vanquish disease and heal a failing body combines noble intention with a kind of superhuman power. It can make a doctor look—and sometimes feel—a little like a god. It can also justify and render ordinary certain actions, like cutting apart a dead woman’s body, which would normally seem impossible to consider.

My classmates and I are undeniably new to doctoring, but the lessons that the body teaches us are profound and resonant, and they begin to change us. As our understanding of anatomy becomes more comprehensive, we start to see differently not only the structure and function of the body but the beauty of it as well. One day in lecture, Dr. Goslow shows us art slides, and the entire auditorium slips into a darkened, awestruck hush. On the broad screen onto which complicated anatomical diagrams and flowcharts of embryological development are typically projected, breathtaking images flash: Leonardo’s perfect studies of the arms, legs, hips; a detail of Michelangelo’s Libyan Sibyl from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, with her massive shoulders lifting the book of knowledge to the sky. Dr. Goslow shows us pictures of the hands of Rodin’s Burghers of Calais, the feet of the scandalously naked Balzac—both show that odd glory of Rodin, whose stone feet and hands look more perfectly human than my own, than any in flesh I have ever seen. In my mind I picture Camille Claudel’s sculpture L’Âge Mûr, in which a woman on her knees extends her arms, reaches desperately toward her aged and hunched love, departing with the figure of death. I see Picasso’s Blue Nude, seated, with her back turned modestly toward the viewer. The Elgin Marbles, their flexed quadriceps, their forearms rotated to hold what must have been a spear, their headless necks. The limbs were what could be understood about the body uncut and unopened. These limbs are signifiers of strength and expression and intent.

We prepare to leave the lecture hall for lab to attempt to link the bravado of Balzac’s unclothed stance to the blank, openmouthed rigidity of our cadavers; to look closely at their now-motionless limbs and understand what structures lent them movement.

Just as the lights come on and Dr. Goslow is making his final comments about the musculature of the hand, Arnis Abols, the lab manager who maintains the cadavers, pops into the room to ask a quick question. We are all a little in awe of him—Arnis immigrated to America after having lost his hearing in his childhood, but in spite of this he reads lips flawlessly in English. When he enters, his fingers are a flurry of motion as he signs to Dr. Goslow across the room. The room remains silent, and we all watch Arnis’s hands: flexion, extension, adduction, abduction, anastomoses, blood vessels, sap vessels, inosculate, intercommunicate.