chapter ten

An Unsteady Balance

You are a little soul carrying around a corpse.

E PICTETUS

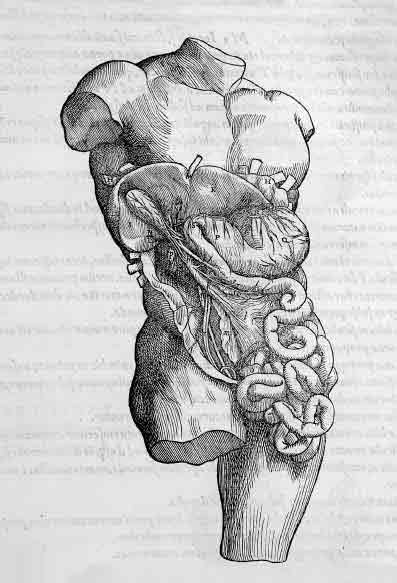

Although we’ve finished the dissection of the male genitals, we will not study their female counterparts for two weeks, so that they can correspond with the uterus in the pelvic dissection. In the interim, on the second day of the abdominal dissection, we open Eve’s abdomen more fully to examine her internal organs. The mood in the lab room is light, with the stress of the first exam behind us and the transition from male genitals to guts a welcome step down in emotional intensity. Although the initial cuts into the abdomen have removed the skin and exposed the abdominal musculature, we still need to cut through the abdominal wall. Trip grudgingly volunteers to be the one to make the incision, and once the belly is opened, all we see is a chaotic mess of fat and intestines. Raj is reading our instructions aloud from the Dissector and at first doesn’t raise his head from the pages to see what we see. He reads the names of the discrete organs and anatomic landmarks we’re supposed to find: “Okay, identify the fundus, body, antrum, and pylorus of the stomach. Then find the hepatogastric and hepatoduodenal ligaments of the lesser omentum, noting the greater omentum with its gastrocolic and gastrosplenic portions.” Tripler begins laughing so hard that she is practically in tears.

“Oh, yeah, I see the distinction between the gastrocolic and gastrosplenic portions quite clearly here, don’t you, Christine?” She gestures to the indistinguishable innards and can barely get the whole sentence out. She has to force herself to stop laughing in order to breathe.

“And here is the greater curvature of guts,” I respond, giggling, “followed by the lesser curvature of chitlins and the ligament of tripe.” For a moment Raj is disoriented, searching frantically for the names of our newfound structures in the Dissector. When he looks up, he breathes a deep sigh of frustration while waiting for Trip and me to compose ourselves and resume.

The room is full of discussion about how jam-packed the abdomen is with viscera. Two students from a table across the lab each take an end of the intestines they’ve cut free from their cadaver and step back from each other until the intestines are fully extended between them, like a clothesline. They are at least ten feet apart. We all stare at them, half amazed by just how much intestine there is and half stunned by the shift in all of us that has made it permissible—even natural—to do something like string out someone’s innards to see how long they can stretch. A third member of the table bends his body backward and walks toward the line of intestine, as if he is about to limbo beneath it. He stops and laughs with no intention of going through with it, a perfect expression of the tenuous balance of appropriateness we are beginning to find—of the transformation we are in the midst of negotiating: I will nod in the direction of humor, of absurdity, but I will stop myself before I cross the line into disrespect.

We do eventually find Eve’s stomach, which, paradoxically, is the largest of any of the cadavers’ in the lab. Like the others it is a flat sac, pale pink and nondescript but for the thick, ringed pylorus, from the Greek word meaning “gatekeeper.” The pylorus tightens and relaxes, determining when the gastric contents can pass into the intestines. Though the interrelationship among the stomach, pylorus, and intestines is straightforward enough, the abdomen introduces a host of complex anatomical intertwinings. The green fist of the gallbladder stores bile made in the liver and releases it into the duodenal portion of the intestine via a pathway of tortuous ducts. The broad portal vein brings blood through the liver for filtration with its multiple anastomoses. A seemingly endless number of arterial branches provide the gut its blood supply. The network of structures and names is utterly alien to us—we will not learn the functions of many of these organs for weeks yet. We have no systematic understanding either, of the ducts and veins and arteries and lymph nodes running through the region.

Confusing as the complexity of the abdomen is, we soon learn that the story of how it forms is even more mind-boggling. Dale delivers the lecture on the fetal development of the abdomen. He hands out a series of color diagrams that are sequential pictures of stages of what he has humorously—but also pretty accurately—called “The Dance of the Intestines.” In it we learn that in order for our esophagus, stomach, intestines, liver, and pancreas to form and position themselves correctly, buds of organs come off the foregut, a precursor to the digestive tract. These buds “migrate,” literally sliding from one area of the body to another, and, in the case of the pancreas, fuse with buds elsewhere to produce the juvenile form of the developing organ. The stomach then takes shape and begins to rotate. It also begins to grow a first intestinal loop. This loop of intestine actually leaves the fetal body, rotating 90 degrees as it pushes out into the umbilicus. There it continues to grow and then undergoes an additional 180-degree rotation as it returns into the fetal abdomen.

It makes no sense. Dale goes over it multiple times in lecture. He points to the picture representing each stage as he explains the directions of the rotations, the exit, the return. Lex and I look at each other, baffled. When we consult our embryology textbook for an in-depth explanation, we are met with horrific pictures of fetal abnormalities that occur when this rotation goes awry. Our friend George, a frighteningly smart guitar player, suggests we meet at his house that night with Play-Doh, pipe cleaners, and beer to try to reconstruct roughly what happens. We agree, figuring that seeing the evolution in three dimensions and making the movements with our hands may help us understand it.

In the end we spend a few hours accumulating our supplies and trying to mold organs out of Play-Doh, only to make no more sense of the embryology than when we began. We decide instead to cook omelettes and drink Guinness while going over our notes from the week. We make a trivia game out of it. I name a structure in the abdomen, then ask Lex a question about its embryology, or innervation, or blood supply. Lex answers—if he’s right, he asks George another question about the same structure; if he’s wrong, George tries to answer the original question correctly, then asks me a different one. We go around and around with as many structures as we can think of. Lex knows the answers to twice as many questions as I do, and George knows twice as many as both of us combined, but the atmosphere is silly and light. Before Lex and I leave, we try to go over Dale’s pictures one last time, to no avail, and then head home.

Dale’s drawings force us to begin to think about the new ways in which we are called upon to visualize the body. Obviously, when we are with our cadavers, we look at them mostly from only one perspective. We look down into their newly opened spaces and study what we see. We may pick up the stomach or the heart and turn it in our hands, but we must learn to see the insides of the body from multiple perspectives, an ability that our dissections cannot help us acquire.

In another perspective, the cross-section, the body is drawn or viewed in many slices, like a loaf of bread. Learning cross-sectional anatomy is an important skill, which we will be called upon to use in our clinical rotations. We will need to look at CT scans of brains to try to determine, on the basis of those cross-sectional views, whether the ventricles are enlarged or whether there is blood beneath some of the brain’s protective layers. We will need to make decisions about whether a patient requires surgery based on cross-sectional images that show inflammation, tumors, or some other abnormal anatomy. But the perspective we get on the body from dissection alone does not allow us to envision the relative position of one vessel to another—even one organ to another—in cross section.

In order to teach us to read cross-sectional views, Plexiglas squares are scattered on lab benches all around the periphery of the room. Cross sections of an actual body are embedded in these squares. They are stored in a back room, where they are kept in museum drawers that might elsewhere hold ancient maps or pages from illuminated manuscripts. Dale and Dr. Goslow bring out several squares at a time that correspond with the part of the body we’re studying. Rounds of bone are surrounded by rounds of muscle, like grayed cuts of meat. The sections offer a helpful view, bizarre as it is, of how all of the structures interconnect, no organ or muscle working in isolation. In the midst of the abdominal dissection, which can feel like a disorienting mess, the squares help bring order to the chaos.

The strangest Plexiglas sections are those of the head, because here the body’s recognizable exterior features refuse to hide. The sections are numbered, beginning with the uppermost cut of the scalp as section one. Section number four reveals a beautiful view of the brain’s tissue, vasculature, and ventricles but also contains the eyebrows. Section five shows a look into the sockets of the eyes and the beginnings of the cerebellum, but most striking are the halved ears that jut out on two sections. In lab one day, I pick up each of the head sections, and look at them not from the top, as we are meant to, but from the side, where the facial features are, in inch-by-inch increments. Here the eyelids and lashes, here a section of a nose, pores visible, hair in the nostrils. Here the lip in front of the slice of jawbone, of flat, pink tongue. Here whiskers.

I wonder about this man—we first understood he was a man from the relative absence of breast tissue in his thoracic sections and later from the sliced segments of his penis and testicles. Some of my classmates had a guess even earlier, when they picked up a Plexiglas piece and looked at it from the side, seeing many dark hairs on the preserved surface of the skin. Could he have possibly chosen for this to be the way in which his body was to be used? And why does the way his body has been sliced and preserved strike me as more disconcerting than the cuts and the parceling we are doing to Eve? Is it simply that I have become accustomed to the process of dissecting the body as a whole, I wonder, a whole that retains—at least up until now—its human shape? Or is there something reassuring about the knowledge that Eve will eventually be cremated, will be delivered from this state in which I am keeping her? Is it the permanence of this sectioned man that so disarms?

I ask Dr. Goslow where these Plexiglas sections come from; how does one go about purchasing a man in one-inch increments? As is turns out, the answer is that you send a cadaver and twenty-two thousand dollars to a guy named Davy in Kentucky, who will embed the body in plastic and then cut it into slices with a band saw.

As the abdominal dissection progresses, we discover that Eve does not have a gallbladder. Unlike the absence of her umbilicus, this does not raise our eyebrows. Instead of assuming some mythical origin as an explanation, we assume that she has had her gallbladder removed, a cholecystectomy, a procedure we will see many, many times in our surgical rotations. Patients will come in with sharp, severe pain along their right sides, and we will accompany them into the operating room to “drive” the laparoscopic camera the surgeons will poke into their bellies, then watch the green sac be clamped off from its blood supply and bile ducts and removed from the body for good. Sometimes the sac will break and the thick, green-brown ooze of bile will spill into the patient’s abdomen, perhaps with small white stones floating along, and the surgeons will have to thoroughly rinse the abdominal cavity (an action they poetically call irrigation, as if they are encouraging crops to grow) so that the bile doesn’t irritate the other abdominal organs or the walls of the cavity.

The eerie, alien appearance of bile allows one easily to understand its historical demonization as a bodily fluid with the capacity to wreak havoc on the balance of health. In fact, bile was known as “choler” until the eighteenth century, from the Greek cholera, which the OED defines as “the name of a disease, including ‘bilious’ (jaundice) disorders.” The Greek bile meant “bitter anger” and became the ordinary name of one of the four humors (cholera, melancholia, phlegma, sanguis) whose tenuous balance was said to dictate the state of one’s health and spirit. Initial theories held that in Adam and Eve before the Fall the four humors existed in a precise balance. Mortality, however, brought with it a perpetual imbalance, in which one humor was always in recognizable surplus and another therefore in deficit. Bile was said to be the one of the four humors that caused “irascibility of temper.” Chaucer is responsible for the first documented use of “choler” in 1386:

Dreams are engendered in the too-replete

From vapours in the belly, which compete

With others, too abundant, swollen tight.

No doubt the redness in your dream to-night

Comes from the superfluity and force

Of the red choler in your blood. Of course….

For melancholy choler; let me urge

You free yourself from vapours with a purge….

And purge you well beneath and well above.

Now don’t forget it, dear, for God’s own love!

Your face is choleric and shows distension;

Be careful lest the sun in his ascension

Should catch you full of humors, hot and many.

And if he does, my dear, I’ll lay a penny

It means a bout of fever or a breath

Of tertian ague. You may catch your death.

What about this tension of dreams, to which Chaucer alludes? This need to purge oneself lest the imbalance of vapors brings unto our own selves literal or figurative illness or death? Is this the role that humor plays for us—stretching intestines across the room? How does one absorb those things we are not meant to absorb, and maintain an evenness? How to swallow the “melancholy choler” of other people’s sickness and death, to provide strength and support and knowledge to our patients, and yet detach appropriately so that we can lend ourselves fully to the matters of our own lives?

When we finish the abdominal dissection, we can finally study and name the contents of Eve’s abdomen; we understand bile more fully than Chaucer did. And yet some aspects of doctoring—the turns of the fetal gut outside the body, a man preserved in Plexiglas slices—still feel as vaporous as humors.

In the semester that follows anatomy, I will request to observe an autopsy in my pathology course. Having spent months in a room full of cadavers and having taken the body from a whole to its parts, I have no apprehension about attending the autopsy. However, when I enter the morgue, I find I can hardly stand. The body under examination is a young woman who is presumed to have died from complications of multiple sclerosis. Unlike our anatomy cadavers, she is young, has a full head of curly auburn hair, and wears a wedding ring. As you and I would be, she is also still full of blood, and as the autopsy technician makes a sweeping, Y-shaped cut across her chest and abdomen, a hose runs water beneath her and onto the table to course away her blood.

In the cavity of her body are the same organs as Eve had, but their unembalmed condition means that they are more slippery and more flexible than Eve’s stiffened liver, stomach, and intestines. The surfaces of every organ are covered in a deep red sheen of blood.

The most difficult aspect to tolerate is not looking at this woman’s body but smelling it. She had been found in her home as many as twenty-four hours after she had died, and at the time of autopsy her body’s natural decomposition has already begun. The stench is overpowering, and as her body is opened and organs are removed, the potency is multiplied.

As I stand reeling, while hoping to appear as if I am watching attentively, I will my legs to support my weight. The technician and the pathologists go busily about their work. They weigh and section each organ, looking for visible abnormalities, slip tissue samples into vials for microscopic examination, call out measurements to be recorded, saw open the skull and spine, remove the brain and snip spinal-cord samples, pack the body with sheets to compensate for the vacancy left by the removed organs, replace the skull, and finally sew the trunk and scalp back together with wide stitches. The skin stretches taut with each pull, like hide. The stitches on the head are hidden by hair. If it were not for the Y seam on her naked form, you would never know that this body had been disturbed.

Through all of this, the doctors ask kind, everyday questions of the technician and of each other: How is your daughter’s baseball team faring? When is the continuing-education lecture today? They joke about the backlog of autopsies to be done and the rate at which Rhode Islanders seemed to be dying; they also joke about who should stay behind after the autopsy is finished to flush the blood and specks of organ and flesh into the wide, stainless-steel sink.

One gets accustomed to one’s job, and the normal range of human emotions needles its way into any working space. For my classmates and me, we have begun to realize that this desensitization is a vital part of our rite of passage. We must learn not to be frozen in place by the sight of death, by the sight of nakedness, by disease and the body cut open. We will be called upon to act calmly and ably when we are confronted with the body in crisis. We must begin to individually shape how we will cope with the impact of these extraordinary moments of urgency and whether those coping mechanisms take a healthy or unhealthy form.

I will more fully appreciate the incremental fashion in which we are introduced to the body in trauma two years later when, during an elective pathology course at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, I participate in autopsies with the histopathology staff. My first is a twenty-three-year old kid who had died the night before in a motorcycle accident. Though I witness several autopsies over the course of my time at the college, this is the one that distresses me the most. Willy, the autopsy technician, tells me how the young man died: A metal post had been bent down so that it extended into the road, and when he rode by on his motorbike, the post hit him in his side. When the medics arrived, he was standing, telling the medics what happened. He had a few scrapes and said that his side and shoulder hurt, but he wasn’t bleeding and had no visible serious injuries. The ambulance drove him to the hospital, and when it arrived at the emergency room, the young man was dead.

I’m working with the Nigerian pathologist, Ade. He takes me down to the postmortem suite, where he gives me scrubs to change into and a pair of once-white, bloodstained rubber boots. He also hands me a surgical bonnet, gown, gloves, and a green plastic apron. Once properly suited, we enter the autopsy room, and I’m aware that I’m subconsciously holding my hands in front of my chest, being careful not to brush up against anything in the room, as if we’re about to perform surgery and need to avoid contamination.

Ade laughs. “This isn’t the OR, you know.” And I do, but these encounters with the newly dead can be jarring enough to displace reason. Once, during a different autopsy, I leave the postmortem suite to look for a ruler—the elderly dead man had an unruptured aortic aneurysm, and Ade needs to note its diameter. When I return and swing open the door, I see the old man’s face and I am startled. I had forgotten that anyone but Ade was in the room.

The autopsy of the young man is well under way when we enter the room, and Willy is finishing up. At first I breathe through my mouth, trying not to fully take in the smell. The downside of this tactic is that you never grow accustomed to the odor—the sensory receptors of olfaction never fill. So, after a while, I opt to gradually begin breathing in through my nose, and before long I notice the smell only when new cuts are made or organs are moved, the slick red-brown glazing the stainless steel.

The young man’s thorax and abdomen have already been opened by a long cut and the bone saw. Willy grasps and loosens the trachea and esophagus at the base of the throat, making a clean cut through both tubes. He grips the portion below the cut and pulls it firmly in the direction of the body’s toes. The trachea and esophagus pull up and out, and the structures attached to them follow: the stems of the bronchus and the floppy lungs into which they lead, the heart with its pericardial sac and its great vessels, the stomach, the pancreas, the spleen. Willy uses his scalpel to cut away any connective tissue holding fast to the body and then cuts the organs, removed en bloc away from the intestines, which he also cuts at the level of the rectum and removes. The intestines go into a basin in the sink.

The organs are set on the young man’s feet, at the end of the table where Ade and I stand, so that we can begin to open them. There is blood, of course, and it winds its way along the body’s ankles and pools on the metal table. It also forms a low, still lake in his now-emptied abdomen and rib cage. The young man is pale, but his entire underside is mottled in reds and purples due to the hypostasis of blood. Without the heart’s propulsion and distribution of blood—invisible to us, unwilled, unnoticed—gravity is the body’s strongest force, and the blood sinks as low as it can, flooding the vessels and leaking out to color the tissues. Because he lies on his back, the purple seeps into his back, the undersides of his legs and arms, the heels of his feet, the back of his neck. It looks as if half of him has been terribly bruised.

Apart from all the other autopsies I ever see, the motorcyclist’s body stands out because of the beautiful condition of his organs. When Ade cuts open his vessels, there are no dysmorphic yellow plaques of atherosclerosis, or “hardening of the arteries,” found in every middle-aged and elderly body I see. His liver is smooth and dark, his kidneys shiny and perfect. I see them and think instantly of the comments a transplant surgeon made to a handful of my classmates and me during a small group-teaching session.

“Every state has a transplant list,” he said. “Some waits are longer than others because of the number of patients waiting for organs, but some are longer just because there is a smaller supply of organs. If I have somebody who’s really desperate,” he continued, “I tell them to move to Florida.” Everyone in the group looked quizzically at him. “I’m totally serious. If you’re in a hurry for a transplant, you need to be in a warm-weather state where healthy boys ride too fast on their motorcycles year-round.”

In the autopsy suite, Willy moves back to the kid’s head and, with the scalpel, makes a cut over the top of it, beginning above one ear and ending at the top of the other. What happens next causes me to gasp. Willy slides his thumbs beneath the cut he has just made, beneath the mop of curly blond-brown hair, and peels the scalp down over the face, until the cut edge reaches the body’s chin. He has essentially turned this face inside out, so that where the young man’s features should be is instead the yellow-and-red underside of skin, hair curling oddly from beneath, at the level of his mouth. “Have yeh never seen the head done before, then?” Willy asks me in his thick Dublin accent, having apparently heard my sharp intake of breath.

“I have,” I say. “I just forgot.”

“Well, yeh can leave the room anytime yeh like,” he says, smiling warmly.

“I’ll be fine,” I answer, grinning. “I’m tough.”

He laughs. “So yeh are, then, luv. So yeh are.” I have issued a knee-jerk response, a willful assurance that I can handle whatever medicine throws me.

The reality is that I am affected, profoundly so. As Ade is explaining his postmortem technique for examining the coronary arteries, I am focusing on the poor kid’s hands, pale and cold, and on his feet, now bloodied by eviscerated organs, weighed and waiting to be cut apart and analyzed.

I have come to Ireland with Deborah, who is writing a comic play about an Irish art theft. Later that night in our tiny Dublin apartment when I see her, I find myself holding back the degree of my disturbance. She stops in the middle of typing to ask if anything is bothering me. I tell her that the commute to the hospital is tedious, that I will be happy to be done with the elective. I know that the truth is that I am not sleeping well, that the autopsies have brought back the sleep disturbances I had endured while dissecting Eve three years earlier.

I begin to weep in the kitchen before dinner one night a little while later, and I tell Deborah that it’s awful how life is in someone one moment and gone the next, how I never, ever want that to happen to her. I can no longer tell how much of the emotion I’m feeling is about Deborah—and love and fear and mortality and me—and what is about a poor twenty-three-year-old who ruptured his spleen on his motorbike. One minute he was standing up, talking to the medics, Willy tells another technician who wanders through the room, and the next minute he was dead.

Just as a personal transformation must occur in order to quell the dissonance that dissection generates, a community transformation must occur for anatomical exploration to be embraced and encouraged. The prospect of a dissected body created—and continues to create—a great deal of confusion around ideas of mourning and resurrection. Though in America an increase in the prevalence of cremation testifies to the decreasing emphasis on the body in funerary proceedings, this shift is definitely not universal.

In Ireland, as elsewhere, the corpse, and the tradition of burial, is still a very central part of the mourning process. Those who have come to pay their respects to the family do so by filing past the body and shaking hands with the family beside the casket, sometimes stopping to touch or kiss the body. The tradition includes a graveside service, initiated by a procession of the casket from the church to the graveyard, followed by the whole congregation of mourners. The customary funeral is a weeklong affair, and the number of attendees at the funeral is considered to be a testimony to the life of the deceased. To eliminate the presence of the body—here, the true embodiment of the person whose life is being celebrated—disrupts this process. The result is a kind of cultural disorientation and unease, and it requires a redefinition of one of Ireland’s most anchoring and fundamental societal rituals.

Clive Lee, the anatomy professor at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, invites me to attend a biannual memorial service organized by the medical students, held to honor the people who have donated their bodies to the college. In order to express their gratitude to the bodies from which they have learned, students invite the friends and family members of the donors to gather in the Unitarian church on St. Stephen’s Green. This year’s service is held on a damp, cold January day.

I arrive a half hour early and take a seat in the corner of the sanctuary. Over the course of the next twenty minutes, a steady stream of people fill the pews. It is a crowd of all ages. Some people have come alone and others as large families. I am sitting behind a pair of elderly women. When six more women file in beside them in various states of religious dress, it becomes clear to me that they are all nuns and that many of them are simply not in traditional habits. When it comes time to sing hymns, I sing softly to hear their high, warbly voices that add in harmonies and crescendos. They clearly know the songs and one another’s voices with an intimacy that comes only from years of familiarity. I suspect that it is one of their sisters whom they have come here to honor, and I think of how far a distance they have traveled to arrive at this theological point from Boniface’s edict and Vesalius running to St. Anthony’s basilica for mock absolution. Despite such religious history, the presence of these eight women makes much more logical sense to me. What more complete act of sacrifice and denial of attachment to the material world exists than to relinquish the vessel by which your soul was bound to it?

The nuns in attendance remind me of a phone conversation I had with my father after the autopsy of the young motorcyclist. Over the course of the conversation, he asked how my time at the hospital was going. I recounted to him, without going into much detail, that the process of the autopsy is quite difficult to watch.

“Is it just that the body is treated so brutally?” he asked. I paused for a moment to consider the question, then decided that it wasn’t actually that at all. The process is brutal, I told him, but the upsetting part of the autopsy is not the way the body is handled, but rather that such handling makes no difference whatsoever. What one cannot quite comprehend, in the end, is that no matter what is done to the body, it has absolutely no effect on the person who once inhabited it. The horror is not what is present and cut apart but what has so completely and irreversibly gone.

The idea of a memorial such as this one is not altogether unusual. Many medical schools in the United States hold similar services, some just for the students to express their own appreciation and some, like this one, to which families and friends of the donors are invited. In a paper published in the Anatomical Record, Yale course director Lawrence Rizzolo states that the decision as to whether to invite donors’ families is not necessarily a straightforward one. “Although the last several classes have considered inviting families of the donors,” he writes, “none have chosen to do so.” The ceremony, it seems, has become an institutional means of helping students cope appropriately with the extraordinary moments of doctoring. Rizzolo states that the concern has been that students would not feel comfortable fully expressing the “angst and frustration [associated with dissection] along with their joy and gratitude” if family members of the donors were present.

When Professor Lee steps to the podium of the Dublin church to offer his message to the people who have gathered for the Royal College of Surgeons service, he makes what I perceive to be an important distinction between this service and others by shifting the focus from the donors to the donors’ families. In Ireland’s body-centric mourning culture, this recognition is not just courteous, it is essential. Professor Lee expresses to the families that he understands and appreciates that they have undergone an unusually extended period of mourning. As is appropriate for a society in which bodily donation is so highly uncommon, he says he suspects that there are many in the audience who may not have known anyone else who has donated his or her body to medicine and that he hopes there is comfort in seeing all the other families here whose loved ones have also done so. Finally, and importantly, he thanks the family members for carrying out the wishes of the donors, “despite misgivings which you may have had” about their decisions.

Later I am sitting with Professor Lee in his office in the college, just down the street from the Unitarian church in which the memorial service was held. I tell him how happy I was to have seen the service and how nice I found his comments. He makes clear to me he felt that it was doubly important to address the families for reasons beyond the gratitude expressed by the students. First Professor Lee points out that an American medical school might get three hundred bodies bequeathed to it annually, whereas the number taken in by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland each year would be closer to twenty-five. For this reason, continued normalization of the process of donation and clear communication of the benefits conferred by such an altruistic act are an important investment in helping people consider donation as a viable and much-appreciated option. The second important reason, he explains, is a legal one.

“You can will me your jewelry, your furniture, your clothes, and your family won’t have anything to say about it. You own those things. But, legally, we don’t own our bodies,” he says, gesturing with a kind of shrug meant to underscore the odd lack of logic. “This means that if you designate your body for donation and your son or daughter or spouse can’t stomach the idea of it after you have died, they are under no legal obligation whatsoever to honor your decision.” As he speaks, I begin to understand just how completely earnest, then, his words at the service were, thanking families for looking beyond their own misgivings in order to fulfill the specified wishes of their relatives.

Following the memorial service, all the attendees are invited to gather for refreshments in one of the rooms of the college. The idea is not only to continue to express appreciation to the families but also to allow them a chance to talk with the students whose careers have benefited from their loved ones’ gifts. I did not attend, not wishing to disturb this fragile exchange, but as I filed from the church, I did see one interaction that must also be a benefit of the refreshment hour. Lines from several pews merged at the door, and as they did, two women in front of me recognized one another and said hello. An awkward pause followed, and then one of the women turned back to the other and said, “So it’s both our mums, is it?” The other woman nodded. They both smiled and sighed in a way that seemed to acknowledge both the shared experience of losing a mother and the relief at having said out loud the fact of donation, which had perhaps been a truth at times too difficult to utter.

Mid-January darkness comes to Dublin late in the afternoon, and when I walk home from the church at nearly four o’clock, it is dusk already. On the pond in St. Stephen’s Green, the mallards and a pair of tufted ducks tuck their beaks beneath their wings for sleep, ignoring the toddler throwing clumps of fist-mashed bread toward them with all her might. Behind me a bell rings in a repeated rhythm. It is a handbell held by the side of a limping man whose job it is to lock the park gates. He alerts us all that darkness approaches and we must leave. I stand for a moment longer to take in the last silver glint of the pond’s oval, the floating ducks, the determined bread thrower in her orange coat and black patent-leather shoes. The air is cold and damp, but something about the canopy of trees in the green makes it feel as if every breath is purifying. The man is near me now, the bell ringing more loudly, a beautiful tone that sounds the uneven rhythm of his footfall. I take one last look, walk to the gates, and leave. I wonder if this is what death is like. A nighttime motorcycle ride, a glance at evening’s light on water. A desire to stay to take in the beauty of the world with all its imperfections and a bell that sounds to say the hour has come beyond which we cannot possibly stay.

Just like the culture of detachment, which begins with legends of severed limbs and toll booths, the silence we all adopt marks another initial transformation on the road to becoming a doctor: the initiation into the culture of isolation. I am silent about my deep disturbance when Willy uncovers the young man’s skull because I understand on some fundamental level that I am supposed to be. Here in medicine, because failure and weakness can cost people their lives, it is unacceptable to fail; it is unacceptable to be weak. Admission of either makes one seem unfit for the lofty charge. It is a culture currently blamed on litigiousness, but in truth its origins come from within medicine. Doctors stay up thirty-six hours at a time and subsist on vending-machine fare. They perform emergency surgery while others sleep. They maintain composure when the baby is lodged wrong in the birth canal, when the bone breaks through the skin, when the face is unrecognizably burned away. Part of this comes from necessity. But the problem arises when instead of setting aside our natural reactions, they are denied altogether. Then the culture simply becomes superhuman. And thus in the realm of the superhuman there is no room for human frailty, and admission of it by one risks revealing the illusion of the many. So no one speaks up, and as a result each person believes that she is alone in her experience. To that end, we are left in a profession with the pretense of untouchable greatness and infallibility, but one whose members kill themselves more than any other.

As medical students we are in the interspace between doctor and nondoctor. We have the spontaneous feelings that nondoctors do when we are first exposed to sickness and injury. We feel upset and disgusted and faint. Because we are in the interspace, however, we are aware that we must begin to manage those feelings and that, just as we must not blush when a woman opens her blouse nor cry when helping a family make decisions about a loved one’s care, we must also touch and carry on conversations with patients who have seeping wounds, contagious rashes, disfiguring burns, bizarre delusions.

Allowing the feelings to wash over us in their fullness is no longer reasonable. Yet the idea of reaching the stage where we are unmoved by any of these things that so normally move other people is equally uncomfortable, if not more so. We understand how it can happen. After all, we are laughing now in anatomy lab. A paper in the medical journal Clinical Anatomy states bluntly, “Medical students’ empathy tends to wane with each year of education, and by their third year many medical students want to distance themselves from their patients.” How far are we from becoming the resident I follow on my surgery rotation who has had forty minutes of sleep for the umpteenth night in a row and, when a patient on another resident’s service dies, says, “Why couldn’t Mrs. Z have been under my coverage? Then I’d have one less patient to round on.”

One night, eighteen hours into one of my twenty-four-hour shifts in the surgical intensive-care unit, a family had gathered around their patriarch, Mr. A. The patient’s condition had steadily deteriorated over the course of weeks, and his body, having given out on practically every conceivable level, was being kept alive artificially—a roomful of large, state-of-the-art, whirring machines struggling to do the work that compact human organs had done effortlessly for decades. It had been weeks since Mr. A had shown any sign of consciousness, and there was no indication that he would do so in the future. One by one, the family members began to understand that their much-loved father and grandfather had no hope of improvement, and that the life remaining in him was borrowed from technology, that it no longer had origins in his body or his spirit. The family had gathered together at the bedside to discuss this grave reality, which had been confirmed by the doctors caring for the dying man.

Mr. A’s physician, for whom a surgical resident and I were covering all night, had explained to the family that the ventilator, the dialysis, the endless medications could keep Mr. A alive for an indefinite amount of time in his present condition, but without any hope of improvement. The alternative would be to dial down the ventilator so that Mr. A received fewer breaths each minute. This shift in breathing would gradually mean that increasing amounts of carbon dioxide would accumulate in Mr. A’s blood. Without adequate exhalations to expel what the body must normally breathe out, the failing body would be unable to compensate, and quietly, perhaps almost imperceptibly, in minutes or in hours, Mr. A would die.

After multiple grueling conversations, Mr. A’s eldest son and daughter approached the resident and me. Their faces were dark with grief and drawn by the penetrating fatigue of not just this moment but of the past weeks. Calmly, they informed us that the entire family was in agreement: This kind of existence was not what Mr. A would ever have wanted. His loved ones were surrounding him—they would like for us please to turn down the ventilator, as their doctor had explained was possible. The resident agreed to do so. I nodded as the siblings spoke, in an attempt to support what had to have been a wrenching and awful decision for children to make about their parent. The conversation was a short one, and after it ended, the son wrapped his arm around his sister’s shoulders and they headed back to the family, and their father, in the crowded room.

Once an hour for the next several hours, I quietly knocked and entered Mr. A’s room to check on his exhausted family. Occasionally one or the other of them would leave for a tray of vending-machine coffee or to make a phone call to faraway relatives, but otherwise they remained. When four hours had passed with no apparent change in Mr. A’s condition, I took the resident aside. “I know I haven’t seen this kind of thing before,” I said, “but are you surprised that Mr. A is still alive?”

“Not at all,” he replied with a half smile. “In fact, I would have been surprised otherwise, since I haven’t touched his vent since we came on this morning.” I nearly stumbled as he spoke, picturing this family who was emptied of all reserves, awaiting their unenviable, but peaceful, finality of grief. My shock must have been easily recognizable, because the resident quickly continued, “Have you seen the paperwork I have to do for every death on this unit? His own doctor will be on in six hours and can dial the vent down then. No one dies on my clock.”

We say we’ll never get there. I say I’ll never be that. But as doctors-in-training, we are reshaping the ways in which we react—in fact we are suppressing universal reactions of fear and grief and horror. Will I be able to suppress some but not all? Will I be able to detach from strangers and maintain the humanity with which I would respond to loved ones in similar circumstances? But then am I not bound to consider each patient as I would want my brother to be considered? My partner? My niece? The lines blur, and I am left feeling dissatisfied. I do not wish to blunt the spectrum of my feelings, to lose the discomfort I feel in violent movies, to lack empathy at the bedside of a dying patient. I do not wish to hear “stroke” and think of the distribution of vessels to the brain and the territories they serve instead of my grandmother’s now-curled left hand and stooped walk. I do not wish to make love to my partner and think, Latissimus dorsi, umbilicus, myocardium. How much of becoming a doctor demands releasing the well-known and well-loved parts of my self?