chapter eleven

Pelvis

…mother

of my mother, old bone

tunnel through which I came.

you are sinking down into

your own veins, fingers

folding back into the hand,

day by day a slow retreat…

MARGARET TWOOD, “FIVE POEMS FOR GRANDMOTHERS”

These initial forays into the body and disease inherently force my classmates and me to think about and define the boundaries of life and death. In strange ways the origin and the end of life sometimes overlap. One day in my final year of medical school, I am spending the afternoon on an inpatient hospice unit with Dr. Nancy Long, a wonderful end-of-life specialist. As we are rounding on patients, a dying woman’s family approaches us. Of their loved one’s final moments, they ask, full of grief, “How much longer can we expect this to go on?”

Dr. Long begins quietly, “Once someone starts to die, it is very much like when someone starts to be born. Just like labor, we know for certain that active dying means we are in the final stages, but we cannot say for certain when the end will come.” Here she stops for a moment, until the family nods for her to continue. “A natural and human process has begun, and it has its own pace. We can only be here to participate in it and wait for it to progress.” It seems right somehow that despite all the interventions we will learn over the course of our medical education, life is bracketed by forces that cannot ultimately be controlled.

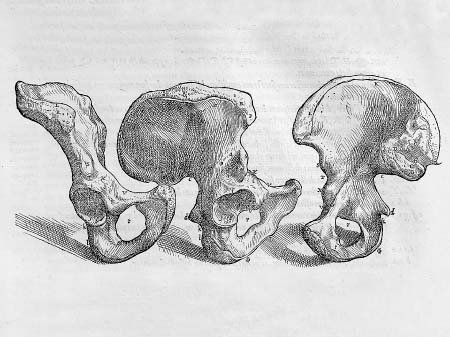

For me, thoughts about life’s boundaries emerge at both expected and unexpected times throughout medical school. Some of the most concentrated contemplation comes for me during the pelvic dissection in the seventh week of anatomy. I love the shape of the pelvis, as I have since the first day when I carried home my bone box and held that single pelvic bone in my hand. When we are learning the pelvic geography, Dr. Goslow brings a massive model of the bones to lecture, the size that an elephant might have. The model seems to me like a beautiful sculpture, with perfect, proportional, continuous lines and series of holes whose dimensions shift as the structure rotates: from one angle, mirror images of near circles separated by bone; from another, asymmetrical ovals; from another, creases of light, overlapping and oblong. The language of these bones slides along their edges. Os coxae, the hip bones. Their three parts, with names like flowers: ilium, ischium, pubis. The place where all three parts fuse: acetabulum. Coccyx: ancestral vertebrae—a tail?—now fused. The pelvic brim, as if water spills over it. The obturator foramen, the ischial tuberosity, the pubic arch, the ischial spine, the sciatic foramina. The names are so geographic it is impossible not to lose oneself in the massive model. Brim, arch, spine. The ligament names like a call to prayer: sacrospinous, sacrotuberous. Sacrosanct.

Vesalius’s illustration of the bony pelvis and its accompanying annotation reflect an unusual lack of specificity when it comes to the nomenclature of these bones. Vesalius names the bone without naming it. That is, he calls it the innominate bone, or “the bone with no name.” Galen had given no name to the bone. Vesalius, then, as a follower of Galen, subsequently refers to the bone as innominate, perhaps in deference to Galen’s (conscious?) omission. Maybe it is this bone’s inability to be encapsulated by language that makes me marvel. Or, equally probable, the fact that it is so unlike any other bone—or organic object—I know. Its effect is as when we see a lady slipper, and think, Yes, flower, but utterly different from everything else that blooms.

It may also be that there is something Platonic about this shape for me. Does the form resonate with me on some subconscious level, as if to say, Motherhood, birth canal, womb? Is my response to this shape different now, as I begin to feel a primal yearning for pregnancy? Or is this purely an echo of the unmistakable shape of the mothering from which I benefited? My young and beautiful mother, slim and sure of her body, wading backward in a hip-hugging two-piece swimsuit in the shallows of Higgins Lake on a northern Michigan summer day, gesturing for me to follow. How old am I in this memory? Two? Three? The orange swimsuit is what I fix my eyes on, determined to reach her. I am aimed toward reassurance and comfort. To her lap where I lay my head in the evenings after dinner. There she absentmindedly sorts through my tangled waves of still-damp hair and laughs with my handsome, larger-than-life father. Sleepy from swimming and sun, I follow the conversation around the room from my dad and mom to my New York artist aunt and uncle, my loud and wonderful grandmother, smoking her Winstons and retelling stories about the neighbors, my grandfather in light summer clothes with his sweet disposition and big, quiet smile.

My grandmother had this pelvic shape, too, bending over in her Indiana garden to hoe between the rows of peas, to dig potatoes, to let fat red and yellow tomatoes fall off the vine and into her hands. I can see her hips, strong and lean like a swimmer’s, outlined in her white cotton pants as she lifts a bushel basket of apples into the station wagon or the tractor cart, and then again as she hoists tray upon tray of apples—Jonathan, Golden Delicious, Winesap—into the cider press. This shape of nurturing resonates. This outline of womanhood differentiated the bodies of my mother and grandmother from their husbands in their square swim trunks and khaki pants, from my brother’s straight and lanky shape—all arms and legs, as if the torso were an afterthought—from my own thick child’s form, which always seemed to me too big, too shapeless.

The pelvic dissection begins with the female genitalia. Nearly two months in the anatomy lab are behind us, but, regardless, this dissection is very strange to do. It feels so clinical and cold to peel back the labia with tweezers, to find the clitoris with a probe, to cut away the labia majora, exposing the labia minora and the vaginal opening whose numerous folds make it seem as if they cower in the light and turn in on themselves, so accustomed to being tucked away and shrouded. And whether it is because Eve’s gender—and genitalia—are the same as my own or because of the interiority of the female genitals compared to the male, the probing and pulling feels particularly invasive. A probe does not belong in a woman’s urethra. These are not parts that are meant to be touched by metal. In addition, it is an unnatural feeling to put a gloved finger into a stranger’s vagina, and how much more a dead stranger?

When we are trained to do gynecological exams on the hospital wards, we will be told to tell the patients what we will be doing far before we do it: “You’ll feel my finger at your vagina. I’m going to insert the speculum now. Some cold jelly and my two fingers going inside.” The implication is that communication will decrease the discomfort of surprise, of unknowing. And also that the advance warning gives women time to respond: “The big speculum always hurts me. Can you use a smaller one?” or, “I hate this, so do it as quickly as you can,” or even, “Once you’ve had children, you don’t care what has to be done down there!” In any case, there is a dialogue. A seeking of permission, in essence, to enter into an intimate space.

Obviously, this is not possible with Eve, and I understand that she must have known that implicit in her agreement to have her body taken apart by students would be these moments of interiority. Still, the region is far more charged for us than was the relatively superficial forearm or even the distant, never-touched ventricles of the heart and knuckled shape of the spleen. The interiority of the genitals is associated with intimacy and in that way differs broadly from that of other parts of the body. These are spaces reserved for passion, for birth or the processes that allow it. This is not the neutral realm of the esophagus, the abdominal cavity, or the interior of the chest wall.

There are spaces in the body that lack the kind of emotional weight that the genitals possess but that share the idea of bodily entrance. At the mild end of the spectrum, we feel this when hooking a probe through the nostrils or deep into the back of the mouth. At the more extreme end, it is unnatural to push a probe through the eustachian tube of the ear, and it is an awful feeling to poke metal into the orifice of the eye. These are deeply held, practically innate lessons that even my toddler niece and nephew know—you don’t put anything into these spaces in your body, and certainly not in anyone else’s. You do not probe the ear, the socket of the eye, lest you cause damage. And we cannot help but feel as though we are.

The pelvic dissection does not get easier in the week after we have finished dissecting Eve’s genitals. The summer before beginning medical school, I learned of the procedure performed in anatomy lab called the pelvic hemisection, in which the pelvis is literally sawed through at right angles so that one of the legs can be rolled to the side and removed. Since that time I have been dreading the dissection, and I do not now feel any less apprehensive about it. The night before the scheduled hemisection, I have no appetite and snap at Deborah for no reason. I sleep poorly, and when I do sleep, I clench my teeth so tightly that when I wake in the morning, my jaw aches and will not fully open. I try to tell myself that these are the physical manifestations of a mounting workload in all my medical-school classes, of the conceptual difficulty of the physiology of the kidney, of the seemingly impossible differentiation of tissue samples on slides in our histology course. What I know is that these are the physical manifestations of being asked to do something truly horrible to a body, to push beyond any shred of comfort or even interest. These are the sensations of breaking apart a previously inviolable internal wall.

The Dissector, in the end, does not pull punches. “Hemisection of the pelvis offers a unique opportunity to view many structures that lie deep within the pelvis and affords a chance to trace nerves and vessels,” it begins. Then, frankly, “Check with your instructor to determine if you should complete this dissection.”

The day is a difficult and emotional one. To begin, we pry Eve’s legs apart as instructed, and put a rectangular wooden block between her ankles. We use the scalpel to make deep cuts through all the soft tissue we can, cutting into the body’s side, above her iliac crest to the spine, and directly, inconceivably, down the middle of her vagina, clitoris, uterus, rectum, bladder. There is a different tone to the day for the whole room, and it is less tolerant of the lightness that has felt acceptable at other times.

When the soft-tissue cut is made, we are to take a ten-inch-long manual bone saw and saw through the spine crosswise and then up through the center of the pubic symphysis, the sacrum, and the lowest lumbar vertebrae (which means we must begin by sawing through the initial, lengthwise cut in the vagina and uterus). As we read the instructions in the Dissector, I feel dread in the pit of my stomach and remember the talk I have given myself that morning during my commute into school: I was the one to saw the rib cage. I skinned her hand and cut off one of her labia majora. I don’t have to saw her pelvis. I know that Tripler won’t volunteer to do it either, so I decide I will let Raj do it, or let him ask Trip or Tamara to.

I expect to feel shaken and upset once the sectioning actually begins. I do, partially. The sound of the bone saw is terrible, and we hear it, portentous, in other groups before we start the process ourselves. As is typical for them, Roxanne’s tablemates are gung ho, and we are still cutting through the soft tissue when they have completely cut their man in two at the waist, are holding his legs in the air, with his low spine propped up on the table, and are sawing between the detached legs like mad. When the leg comes off, they let out a kind of cheer. The rest of the room lets out a deflated, instinctive groan of disapproval, and I feel sad for the spectacle of it. In contrast, our table’s trepidation is evident. We wait and wait to begin, insisting that we need Dale or Dr. Goslow to help us find the barely visible bulbospongiosus fibers in Eve’s innermost labia before we begin the process that will certainly render them unrecognizable.

Raj does begin the sawing, and when he does, I am holding Eve’s right leg, pulling it slightly to the side. Trip is talking about going to visit her parents in Newport for the weekend, and I focus as much as I can on her mouth moving and her chirpy, high-pitched voice. The sawing goes on for a very long time—longer than anyone would have expected—and we stop several times to assess our progress, to break for lunch, to see a prosection. Raj and I are alone to do the final push of it, and he grows tired from all the sawing just before the end, so I reluctantly take over, sawing into Eve’s vertebrae. It is my cut that causes her leg to roll to the side, exposing her split, apricot-size uterus and its thick inner wall. She is now in two parts—her amputated leg and the body from which it came.

This dissection causes a kind of shift in the emotional momentum of the course for my lab partners and me. Where we had been growing increasingly at ease with the actions we performed upon Eve, we now grow less so. And where her partitioned body had begun to resemble a human being less and less, it now harbors new and undeniable reminders—like this small fist of uterus—of the living body that Eve once was. Each cut we make into Eve’s flesh should reiterate her lifelessness, and yet the distinction between “alive” and “dead” is not always as evident as it rationally should be.

My classmates and I are not the first to stumble into the netherworld of these boundaries between life and death. Countless cultural rituals and superstitions surround the liminal period between death and burial. In many modern and historical cultures, there exists a widespread belief in a sort of liminal state of consciousness immediately following death. The duration of this period differs significantly—in some instances just until the body’s temperature becomes cold, in others until some spiritual quest is resolved or reconciliation occurs; in many there is a sense of ongoing personhood or consciousness that is permanent.

Ancient Egyptians, for instance, performed a ceremony in which the mouths of the dead were pried open so that the deceased could speak important passwords in the afterlife. Still today, in rural China, the parents of young men who die as bachelors search for recently deceased unmarried women to whom their sons can be “married” in death. The couples are interred together in the hopes that they will have happy afterlives. The wealthiest of these families may slaughter an animal and have a reception to honor the union; those too poor to afford even a dead woman’s dowry may bury their sons beside bridal figures made of straw.

In nineteenth-century Britain, it was commonly thought that the unburied corpse might return to life. In recognition of this possibility, food and wine were left by the body, so that hunger and thirst would not go unsatisfied if the corpse should awaken. Even if the body were to remain dead, it was commonly believed to be able to defend its wishes, and help the cause of justice in the case of wrongdoing. Many traditions state that the corpse was capable of showing displeasure—a murder victim would speak or begin to bleed if the murderer walked into the room, as would the deceased person whose falsified will was read in his or her presence. The most dubious law surrounding the newly dead established their ability to enter into agreements and sign documents—any mark or signature taken from the hand of the corpse was held in the same legal regard as one made before death, so long as the mark was made while the body was still warm.

As is true for so many beliefs and superstitions, it is likely that these initially arose from real circumstances: remnants of blood that happened to come into view when the body was shifted by an unlucky mourner’s touch, a last release of air from the mouth as the muscles of respiration began to collapse. And if we, with our broad base of knowledge and highly sensitive medical equipment, at times struggle with the definitions of life and death, it is not surprising that it would be murky territory for those who relied upon the presence or absence of the fog of breath on a mirror to delineate between the two. Indeed, the popular lack of confidence in the ability to resolutely determine death led to fears of being buried alive. Hans Christian Andersen, for instance, is said to have propped a note up on his nightstand each night before sleep that read, “I am not dead.”

Strange superstitions also surrounded the bodies of executed criminals during the nineteenth century. It is tempting to think that the superstitions arose from a sentiment that I, too, have had: an inability to fully believe that once dead, the people we have known lack any powers or abilities at all. Yet the specific power that criminal bodies seemed to possess may, in fact, have indicated a belief in the powers of dark forces rather than a disbelief in the powers of death. Both of the two most commonly held superstitions involved the criminals’ hands but were used to very different effect.

The “Dead Hand” was technically the severed hand of any corpse, thought to possess healing powers. The most powerful Dead Hands, however, were those that had once belonged to newly executed criminals or suicide victims. The Dead Hand was used to rub ailing body parts and was particularly helpful for sufferers of cancer, tuberculosis, warts and other sores, but it was also said to help with neck and throat problems and (though the treatment conjures disturbing images) female infertility! Incongruously, the severed hand was also believed to speed the churning of butter when used to stir the milk.

The “Hand of Glory,” conversely, despite its rather religious-sounding name, was used by witches and thieves throughout Europe. The hand of a hanged felon was severed from a body still on the gallows, pickled and dried. A candle, made in part from the fat of a hanged man, was fixed between the fingers. When lit, such a candle would cause occupants of a home to fall into a deep slumber, uninterruptible by even the greatest noise, allowing thieves to work in the house at will. Some variations of the Hand of Glory lit the fingers of the hand itself, rather than a mounted candle. If the finger would not stay lit, it was said to indicate that someone in the house remained awake. Perhaps this omen was ignored by the burglars who were discovered using just such a Hand of Glory in a foiled robbery attempt in rural Ireland as recently as 1831.

Various spiritual beliefs shaped ideas about the afterlife. In a wonderful Norse tale, ghosts haunt an Icelandic castle. The ghosts take claim of the fireplaced rooms and force the owners to the cold and gloomy recesses of their home. The owners are intimidated by their unwanted houseguests but eventually are driven to try to reclaim their home. In order to do so, they air their official grievances at a full trial by jury. There the ghosts, who are present, are convicted and sentenced to permanent exile from the castle. Apparently having no choice other than to comply, they do so, thereby leaving the legally ordained, rightful owners in peace.

Pagan as these beliefs may sound, examples abound of religious authority relying on just such principles. Pope Stephen VI, in the ninth century, claimed that his papal predecessor, Formosus, had been disloyal to the church. Stephen actually took the corpse of Formosus to trial, where, after the appropriate proceedings, it was promptly pronounced guilty. As punishment, the right hand was severed from the dead body of the accused, mutilated, and finally, for good measure, thrown into the Tiber.

Though this anecdote of long-ago ecclesiastical judgment is an outrageous one, it does not stand alone as an illustration of the church’s participation in the bodily interspace between life and death. Deborah and I found a vivid example of just this tension while I was researching anatomical history in Italy: the incorrupt corpse of Santa Caterina of Bologna.

St. Catherine’s relics are housed in a small church called Corpus Domini, and when we arrived, the chapel of the saint was closed, the church empty. We rang the buzzer of the convent beside the church and waited a long while. Nothing happened. When we were considering whether we might try to find someone within the church, a female voice came from a tiny speaker above the button: “Si?”

I responded in terribly broken Italian: “Buongiorno. Sorry. No. Speak. Italian. To see. Saint?” The voice came back over the speaker, and I understood her to say that the saint’s chapel was closed. We could come back tomorrow. I tried again: “Leave. Today. Is possible. To see. Saint?”

A long silence. Then in English: “Open door, please.” When I did, no one was there.

“Over there,” Deborah whispered, nodding in the direction of a white wall, which on closer inspection had a white mesh square in the middle, like a confessional screen. Behind it a barely visible dark shape moved.

As we approached, we heard, “Go into church. I will open door in five minutes.”

“Grazie, grazie!” I said, leaning toward the screen, but it was now all white, and any trace of movement had gone.

In the silence of the church, the lock turning in the door sounded like a shot, and we jumped at the noise. When I opened the door, there was no sign of the nun who must have been there only seconds before. With no other option but to go forward, we began walking. The door closed solidly behind us. At the end of a hallway was a very small chapel, glittering with gold, its ceiling ornately painted in pastels. And there, in the center of the room, seated upright in a glass chamber canopied in red-and-gold brocade, was the 541-year-old corpse of Santa Caterina of Bologna.

Unlike countless saints whose bodies are scattered in pieces between tens or even hundreds of churches, St. Catherine’s body is completely intact. She wears a traditional habit, and her bare toes peek out from beneath its hem. In the center of the chapel wall directly across from Catherine is a porthole through which the saint’s face—a wizened dark mahogany hue like her hands and toes—can be seen from the sanctuary of the church.

Reliquaries from other saints surround Catherine. A skull and a pile of bones rest on a shelf. A large glass box holds a board with mounted rows of teeth—too many to have come from one mouth. Numerous small boxes contain the staples of holy containers found in nearly every church in Italy: vials of saintly blood, bits of skin and fingernails, the small bones of the wrist, a desiccated toe. It is impossible to know how many saints are represented here, their fragments positioned to pay homage to the upright corpse. Catherine’s head is cocked a little, as if she is listening to something that the bits of saints might say.

Deborah and I were alone in the chapel with a person who died in 1463. The nun whose shadowy presence led us here was nowhere to be seen. We tried to behave piously, while at the same time desperate to glance at each other in the total silence to say, Can you believe this? Two offering boxes were positioned at Catherine’s feet, along with two benches upon which we knelt until a sudden whoosh to my right nearly made me jump out of my skin. It was the disappearing nun, who slid open a fabric window through which she must have watched us arrive. I stood to thank her. She did not meet my eyes but wordlessly slipped something through the window, closed the fabric, and was gone. I picked up what she left us: two tiny prayer cards in English. On the front, in glossy color, was a photograph of the dead saint on her golden throne.

Catherine of Bologna was an accomplished miniaturist and was therefore named the patron saint of artists. In death she is said to have appeared to a seventeenth-century nun with proposed designs for the ornate chapel where Deborah and I knelt, so that her incorrupt body could be properly enshrined. As I studied her withered face, I thought that Catherine’s glass-encased corpse was the perfect symbol for the Renaissance collision of art and science and religion and death. In a faith that forbade dissection, Catherine would be the patron saint of Leonardo in nearby Vinci, eleven years old when Catherine died, or Michelangelo, born twelve years after her death—two artists who zealously attended dissections, even took legs or heads or bodies to their own studios for study. In an era that condemned the fact that dissection denied the dead the burial necessary for the soul’s rest, resurrection, and eternal life, Catherine’s sanctified corpse was removed from the grave (and placed in a not particularly rest-inducing position) with no intention of reburial. And in countless churches, the enshrined bits and pieces of the most religiously revered human bodies in the Catholic faith are displayed, partitioned and segmented, cleaved and severed and torn. If there is a difference between the physical treatment of these saints’ bodies and that of the bodies of the dissected, which were deemed desecrated, I cannot see it. And, I suspect, neither could Vesalius, kneeling before the tongue and larynx of St. Anthony of Padua.

When Deborah and I left the holy corpse and reentered the sanctuary, we stood in front of the round window that looked into the chapel. Santa Caterina’s face was framed in a circle of light, and though we could not see any more of her body, or the room, a shimmer of gold encircled her. After only a moment, the light snapped off. The ghostly nun must have known we left and, once we did, turned out the chapel lights. When we peered into the circle, we could now see only the round glass of the window, a framed lens of darkness in which our own reflected faces were visible.

Though her purportedly incorruptible flesh and her ornate chapel give St. Catherine a relatively unique position among relics, the idea of a holy body on display rather than buried is certainly not an anomaly. One of the most vivid, and currently accessible, examples of the church’s invitation to the living to view the holy dead is the crypt of Santa Maria della Concezione, in the heart of downtown Rome. The church’s front looks like any other among the hundreds that dot the Roman streets and alleyways, and even the presence of a crypt in any such church is more the rule than the exception. In fact, the only clue that even hints at the oddities behind the doors of Santa Maria della Concezione is the name of the street leading to the church: Via dei Cappuccini—the Street of the Capuchins.

Beneath the sanctuary of Santa Maria della Concezione, the bones of four thousand Capuchin friars have been arranged in a series of chapels that, even after my time in anatomical museums and conducting cadaveric dissection, remain the most bizarre thing I have seen. The skeletons of monks, still clothed in their dark brown tunics, stand hunched in arched spaces. Between and over them are the meticulously stacked bones of their brethren, their leg and arm bones, their jawless skulls.

Without question it is not the bodies that unnerve the most, or even the piles of bones that, if one begins to count how many lives are represented by each sacrum or jawbone, cause the mind to spin and reel. The most disconcerting element of the crypt is that the bones are used not just as memorials or relics but omni-presently as décor, which is injected with a creepy kind of whimsy. From the ceilings hang illuminated chandeliers of cantilevered arm bones and clavicles. The doorways between the chapels are outlined by a filigree of looping ribs. Half pelvises on the walls and ceilings overlap at a central point, flowering out in petaled whorls, and vertebrae are gathered in clusters, forming oddly beautiful wreaths.

In some spots the collages of bone convey portentous, tempus fugit–style messages of mortality: The pointed base of one sacrum abuts the base of another so that they, outlined by matching clavicles, form the shape of an hourglass. Two scapulae branch out from the sides of a skull, like wings. On one ceiling the skeleton of a child is mounted—one of three nephews of Pope Urban VIII on display in the crypts. In one small hand, he holds a grim reaper’s scythe. In the other the scales of justice, whose chains are made of finger bones, interlaced and dangling.

There is little explanation of why the crypt is as it is. Informational signs explain that in 1631 the remains of four thousand friars were exhumed, but nothing addresses the question of why the logical thing to do with them was to turn them into bony lamps and flowers. It is the shift away from the solemn idolatry of reliquaries that makes the crypt feel like the playground of some lone sociopathic monk, until you read further and realize that the crypt was maintained and added to—presumably as a now-incomprehensible act of religious devotion—from 1631 until 1870.

The ongoing decorative arrangement of Capuchin skeletons—and the seventeenth-century construction of the gilded chapel and throne for Santa Caterina—neatly overlapped with the religious and public outrage over anatomical dissection, underscoring a paradoxical—and perhaps evolving—view of the dead body and its importance. Indeed, to deny a body eternal burial was sacrilege. However, whether in medicine or religion, the boundaries of life were beginning to extend, granting dead bodies a role of importance and a chance to improve the lives of those still living.

When we are instructed to split the pelvises of our cadavers in two, it necessarily requires an additional distancing from the life, from the personhood of the bodies. Detached concern. Perhaps because of this, I am, in the end, very tired, but less bothered by the hemisection than I had imagined I would be. The reactions to the day from my classmates, however, are deeply varied. Helen, a warm and peppy twenty-two-year-old, begins to cry during lab. Many people seem testy, angry at jokes their tablemates have made. Everyone understands that the jokes are merely another way to deal with the emotion of the day, but one that in this instance can more easily bleed into presumed disrespect. Everyone looks a bit haggard and seems to wish the day over much sooner than normal. At the end of the day, I think to myself that I have done one of the strangest things I will ever have to do.

The uterus is amazing. The fallopian tubes are obvious, and the tiny fimbria look like a baseball mitt ready to catch the perfectly aimed ovum. I picture a balance that is this day, this pelvic hemisection. One side is weighed down on the balance’s tray by Helen’s tears, by the harsh words I spoke to Deborah the night before the scheduled lab, by the time and the amount of force required to saw between a body’s legs, by the sounds that a joint makes as its connections give and break.

On the other side lies wonder: this small, perfect swell of an elderly woman’s uterus. What a surprise to see in reality the picture of my fertility. Here are the small blue ovaries that cannot be described as anything other than egg-shaped. Here are the fimbria, from the Latin meaning “fringe,” here the fallopian tubes, small, but sturdy and purposeful. And here the uterus; how to imagine that this tiny, misshapen ball stretches and grows to hold a new person within it? How to make sense of its capacity to fiercely and forcefully contract, to push a baby-size baby out of the small tunnel that is its entrance?

It is this moment that makes me wish to speak to Eve. I do not know which weight the balance favors. I do not know whether this new acquisition of knowledge, this vision of her depths is worth what I have done to her. I do not know if it is worth it to me. But from Eve, with her leg sawed off and rolled aside, with her chest now open, her bowels in a bag beneath her, what I wish to know is the story of her uterus. I wish I could ask her: Children, Eve? Joy? Heartbreak? Catastrophe? Passion? Power? I see this small space of hers and wonder how, if at all, it was tied to who she was, to the life she led. I wonder if her bodily womanhood was centered here or someplace else, more subtle, that I would never guess. Nonetheless, I reach into her to touch this space she never saw and wish I could offer it a blessing.

At first, in our training as doctors-to-be, we are given medicine at its most clear-cut. Thankfully—and necessarily—paired with the feelings of transgression we experience during dissections are teaching sessions that are objective, factual, and emotionless. Here is the context that will allow us to think of these elements of the body as functioning parts to a systemic whole. These are the gears of the machine that we may be called upon to find and to fix. So think like a mechanic and pay attention. In general, this works well. We are taught the way the genitals develop in men and women from shared fetal anatomic precursors; this accounts for findings like the small slips of muscle around the labia minora that are elusive, but present, and parallel the more evident muscular structures in the male. In this, our first exposure to the fork in the developmental road of gender, we learn how each fetus, regardless of chromosomal gender, is equipped with the physical tissue for both testes and ovaries and for both male and female external genital structures. We learn that a cascade of hormones causes either the male or female genitalia to take root and grow and, consequently, to cause the opposite gender’s structures to wither and fade.

What we do not learn now, but what we will learn later, is that, like all bodily pathways, there can be wrong turns, missed steps, interrupted directions. We learn that even physical gender—one of the physiologic distinctions we take as the most basic—is not nearly the black-or-white, male-or-female, pink-or-blue differentiation we have classified it to be. In the back of my mind somewhere during this lecture is the disturbed awe I felt while reading John Colapinto’s mind-boggling As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as a Girl—that there are some for whom this developmental fork is not distinct. Robbins’ Pathologic Basis of Disease, the most widely-used pathology textbook in medical schools, acknowledges the murkiness of this territory:

The problem of sexual ambiguity is exceedingly complex…. It will be no surprise to medical students that the sex of an individual can be defined on several levels. Genetic sex is determined by the presence or absence of a Y chromosome. No matter how many X chromosomes are present, a single Y chromosome dictates testicular development and the genetic male gender…. Gonadal sex is based on the histologic characteristics of the gonads. Ductal sex depends on the presence of derivatives of the müllerian or wolffian ducts. Phenotypic, or genital, sex is based on the appearance of the external genitalia. Sexual ambiguity is present whenever there is disagreement among these various criteria for determining sex.

This lack of clear definition—even lack of clarity regarding the criteria for definition—surfaces and resurfaces as a theme in medicine. What is male and what female? When is a person alive, and when dead? At times, in fact at most times, specific knowledge in medicine seems to be better understood than general knowledge. We might know the exact, microscopic ways in which hormones and chromosomes alter embryological tissue to yield a child with both ovarian and testicular tissue, but we cannot with confidence say whether this child is a baby boy or a baby girl. The realization that looms is that the categories upon which we build our understandings of humanity do not leave room for those who fall between them. And as shifting beliefs and medical advances mean that a baby with both a vagina and a penis can no longer be left to die in the wilderness or relegated to circus sideshows or medical exploitation, those who are not easily categorized also do not easily disappear.

When, during my third year of medical school, I am rotating through the surgical intensive-care unit and working twenty-four-hour shifts every other day, I witness firsthand the inexactness of medically defined states—in this case alive versus dead. Mr. W has been in intensive care for two weeks; his skin is totally yellow. His testicles are the size of grapefruits. Mr. W no longer responds to painful stimuli.

“What does that mean?” Deborah asks when I am recounting to her the upsetting condition of Mr. W. I tell her that it means every morning, in our assessment of his condition, we take our thumbnails and push down, hard, in his fingernail beds, and that he doesn’t pull his hands away. I tell her that it means we make a fist and press our knuckles, hard, into Mr. W’s breastbone, and he doesn’t respond. It is the standard way in which the most basic neurological reflex—retraction from pain—is measured, and we do so daily. We pull his always-closed eyelids open and shine our penlights in to see whether his pupils constrict.

“Maybe a little,” says the resident on duty. The attending physician shrugs. I take my light from my white coat pocket, pull his left lid up with my gloved thumb, shine the beam on his pupil, and see nothing. I aim the light away, then back over his pupil. Still nothing. I know that he is not conscious, that we are not even sure how alive he is, that I can’t see any change in his pupils with light, but he still seems to be staring straight at me. Unflinching. I take my thumb away, allow his eye to close.

“It’s subtle,” says the resident.

“So how do you define someone as dead?” Deborah asks when I tell her about Mr. W. I don’t have an answer. We talk about it for hours, even though my schedule has me so tired that I can’t come up with the words I want to use, that I have to ask her to repeat herself, because unpredictably, and unintentionally, my concentration drifts away in the middle of her sentences, and I am thinking about the pattern on our napkins or the twitch in my eyelid that comes on every few hours and has during my whole tired surgical rotation.

This conversation is one we’ll repeat throughout medical school. It is one I raise when I care for a fifty-six-year-old man who has been brought to the hospital by ambulance after having been “down in the field for a long time.” The translation is that he had a heart attack and was resuscitated. But in between those two happenings, enough time passed without his brain getting adequate oxygen that it left him unable to communicate, unresponsive, and yet making disconcerting, patterned movements. The neurologists call them primitive gestures, meaning that they are indicative of nothing purposeful, meaning that his brain has been reduced to putting out meaningless firings of neurons, which meaninglessly move muscles, cause his head to twist to the side, his elbows and wrists to flex, his lips to smack and tongue to protrude. For doctors these symptoms are often a clear indication of the appropriately named cerebral devastation, and a hopeless prognosis. For families these are movements that must offer promise, mustn’t they? If we’re supposed to believe he’s brain-dead, then why are his eyes open? Why is he moving?

“It’s okay, honey, we know you’re in there. You don’t have to convince us that you’re still fighting. We can see it plain as day.” The words spoken by desperate family members are pointed, directed not at their loved one but at us, his medical providers, as if to say, Don’t you try to talk him out of a chance. Are we? The truth is that this is an instance when medicine seems to fly in the face of reason. The other side of the truth is that for every hundred, or thousand, or even ten thousand Mr. W’s who have these symptoms and waste away and never recover, there is the one miraculous story of a woman who comes back from certain brain death, from months or years in a coma, from, the patient’s family says, these exact symptoms. We health-care workers hear this and give a knowing (patronizing?) smile, clear our throats, explain that those instances were probably examples of misdiagnosis, of inadequate testing, that they were probably different and less clear-cut than this scenario.

And even if they were not…And here is the rough truth of it, where the voice trails off. The end of the sentence is this: Even if they were exactly the same as this, and through some miracle of miracles, recovery was made, is it necessarily morally right to keep vigil? To spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on a gamble with odds like the lottery? To allocate medical resources and, dare I say it, perfectly good organs, which could be, if taken right now, nearly guaranteed to give a good chance to someone else, to this long shot of long shots? The answer, almost always, is: Easy for us to say. The answer is that that girl who needs a liver is not my son. My son is here, having just had a terrible motorcycle crash, or a heart attack, or massive surgical complications, and I am on the brink of losing him. The answer is that the utilitarian perspective of resource allocation and odds is a luxury afforded to someone who does not love the body lying in the hospital bed with oddly flexed arms. The answer is that almost no patient’s family can know—can bear to know—just how slim the odds are, let alone acknowledge that and make an irreversible decision based upon it.

These are the kinds of questions I share with Deborah after dinner, after the lights go out. What does it mean to be dead? How, short of the rigid, wrong-colored, breathless, embalmed state of Eve, to define dead from alive? These are the gnawing questions that must be shared in some capacity, or the impossibility of their answers creates a space between doctor and nondoctor that, in any loving relationship, is difficult to reconcile.

And yet I absolutely do not tell Deborah everything. The distinction is wholly mine, completely arbitrary, and I cannot know how much of it is truly a valiant attempt not to disturb her and how much is my own need not to revisit the things that upset me most or, as is sometimes the case, upset me most inexplicably. When I first see a laparoscopic endometrial ablation to stop a woman’s dysfunctional uterine bleeding, I tell Deborah that the inside of the uterus looks soft and pink and red like cotton candy, but I do not tell her that to complete the procedure the resident rolls an electrified metal wheel along all the surfaces, burning out the pink and red in strips until the whole surface is white, tinged with brown char, lunar.

I do not know for certain the first time I see someone die. Which one you count depends on definition, on timing.

In February of my third year, I will run to a room in the veterans’ hospital when the overhead announces, Code Blue, Room 576, Code Blue, Room 576. By the time I arrive from the basement cafeteria, the room is full. Nurses and doctors have run from all over the hospital in response to the announcement. A resident stands in the corner of the room on a chair, shouting instructions. Nurses fill syringes and hand commanded items to other residents: I need another milligram of epinephrine, a new pair of gloves, where the hell is that atropine I need now? A medical student does chest compressions on a pale, lifeless, naked man. One and two and three and four and exhale (breath from strong and living twenty-four-year-old man inflating the lungs of dying seventy-three-year-old man), breathe, exhale again. Every few minutes the resident in the corner shouts, Stop compressions! and all eyes watch the EKG monitor to see whether there are beats on the screen. At other codes I will have seen, there were. This time, and all subsequent times this day, for this man, there will not be. The cycle resumes several times. CPR. Epinephrine. Atropine. Stop compressions! A flat, green line on the monitor.

Was he dead when I arrived? Or dead when the resident on the chair said, “Does anyone have any objections if I call this? Okay. Eleven twenty-nine. Thank you, everybody.”

After the man died, an intern said to me, “You should have gotten in there to do compressions so you know what the ribs feel like when they break. Do you want to try it on him now?”

Which one you count depends on definition, on timing.

It is April of my third year, two months after the code blue at the VA. He is a new patient to hospice that afternoon, and therefore I am assigned to gather his history, do a physical exam. This is not new to me. I have been to hospice one day a week now for four months, and I know what dying people look like. Once they have been sick long enough, as most who are in hospice have, they grow thin. They are pale. When they sleep, which can be all the time, their mouths are open wide. This has its own terminology outside hospice, which was explained to me by a surgery resident. “That’s the O sign, considered a poor prognostic factor, but not as bad as the Q sign,” he said, grinning, referring to the open mouth with the tongue lolling out of whichever corner is most susceptible to gravity.

When death is imminent, the skin mottles. It looks as if reddish blue yarn has been crocheted beneath the skin. The hands and feet typically grow unnaturally cold. Both of these changes are indications of circulatory failure.

Occasionally, paradoxically, the extremities feel as if they are on fire. A last, feverish flare. This I felt once, on the hands of a Portuguese woman who was dying alone, a portrait of Jesus tacked above the head of her bed.

When I enter the room to gather information from the man who has just arrived, I cannot do so. He has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also called Lou Gehrig’s disease. He cannot speak or gesture. In fact, he can move nothing but his eyes. One blink of the left eyelid means yes, the nurse tells me. Two blinks mean no. These are the only movements he can make. Nearly everything else is paralyzed—his arms and legs long ago, his trunk afterward. Then his vocal cords. Only this weekend his ability to swallow. I know that when his diaphragm succumbs, he will suffocate and die. His breathing is becoming progressively more difficult, she tells me. He is forty years old.

He stares at me, unwavering. I introduce myself. I obviously forgo the history and settle for essential information.

Mr. L, are you uncomfortable?

Blink. Yes.

Are you in pain?

Blink. Blink. No.

Is it still hard to breathe?

Blink. Yes.

Is the medicine they gave you to help that making any difference?

Blink. Blink. No.

I’ll be right back.

I walk quickly to find the doctor, and she prepares to give him more medication—morphine to help his shortness of breath and some Ativan, an antianxiety drug, to help calm him. When I ask her why Ativan, she says, “Read this,” and hands me Mr. L’s chart. In a note written by his primary-care physician many months ago, is written, “Mr. L continues to have severe and distinct fear in regards to the potential loss of respiratory function, as has been his primary fear since the day of his diagnosis.”

When I return to his room, I tell him that more medicine is coming and reassure him that it should make his breathing easier. He lies atop his covers, wearing only the adult version of a diaper. He is emaciated. His skeletal feet turn toward one another so that the toes of his left foot overlap those of his right. He shows the textbook signs of respiratory distress. When he breathes, every conceivable muscle seems to try to help him do so. The space beneath the sternum retracts. The spaces between the ribs invert. Even his nostrils are flared to allow as much air to enter as possible.

Are you feeling scared, Mr. L?

Blink. Yes. It is emphatic. And so is the stare that follows.

I tell him that the Ativan is coming, too, in addition to more of the first medicine, that it will help his anxiety. I cannot know whether I am lying. How strong a medication does one need to take away the feeling of terror each of us feels when we cannot get enough air into our lungs? It is felt in asthma attacks. It is felt at high altitudes. With too much exertion. It is felt when we are caught in currents underwater. When we inhale water and cannot stop choking. How much worse when paired with the knowledge that it is a symbol for the end of an irreversible process? How much more do we fear the symptom when we know what the symptom implies?

I do not tell him that I don’t know if the Ativan will touch the fear he feels. And I do not tell him that his is the disease I fear the most of every one I have studied. He is the embodiment of what I never, ever want to experience. What I never want a loved one to know. Give me cancer, if you must. Give me Alzheimer’s. Give me emphysema, congestive heart failure, diabetes. It is this disease that I fear each time my eyelid twitches, each time I feel numbness in an unexpected place. Is it…? Could it possibly be…? Mr. L, please do not ever let me be you.

His parents arrive and, unbidden, deliver the history that I was originally seeking. Mr. L went to the doctor’s two years ago with a limp that wasn’t going away. It was interfering with his rock climbing. Mr. L was an adventurer who worked to support his travels. His home was decorated with maps. His shelves lined with guidebooks. When the limp worsened despite physical therapy, the doctor did further testing. There was no familial history of neurological disease. Mr. L had had no previous significant illnesses. He had no symptoms, other than the limp. With the diagnosis came gradual decline. Mr. L moved back in with his parents and eventually became immobile. This weekend when they fed him, they noticed that the bites of food never left his mouth to travel down his throat. When he began to struggle to breathe, they took him to the hospital, assuming (probably correctly) that he had aspirated some of his food and now had pneumonia, decreasing his ability to breathe fully and enough. Mr. L had designated in a living will that he did not wish to be intubated, to have a machine breathe for him, thus potentially prolonging his life significantly. But with eventual paralysis of his eyelids and then no ability to interact with others at all, despite a fully conscious interior mind, the hospital could do nothing further for him and so transferred him to hospice, where his comfort would be the primary medical goal.

I leave his parents for them to spend time with him and to hopefully help him feel calmer. Moments later his mother rushes up to me, and looks scared. “He’s having a terrible time breathing, and he looks awful,” she says. I find the doctor immediately, and we go to Mr. L’s room, where his father is standing by him, helplessly looking for us to arrive. The hospice nurse is there, answering the parents’ questions, arranging pillows, using a suction device to clear secretions from Mr. L’s mouth when his breath sounds coarse and rattling.

Mr. L’s eyes are open wide, and he is gasping big, irregular breaths. He is a foreboding shade of gray. And though his eyes stare straight at me, it feels to me as if it is only because I am at the foot of his bed, and that is where his eyes happen to be directed. It feels as if he is absent from the gaze. Or perhaps I cannot bear, cannot understand the thought of him trying to communicate something to me in this moment. His parents look to the doctor, who calmly, gently, explains to them that the raking sounds of his breaths sound worse to us than they feel to him due to the medication we have given him and, though he looks distressed, it is unlikely that he feels so. The parents ask what is happening. The nurse says that we never know, but that it seems as if he may be taking his last breaths. The doctor nods in agreement. I am dumbfounded.

The parents each let out their own, independent, primal moans. It is as if this chorus is a parental reflex—what you do when you are told that you are watching your child die. Yet, unlike children at the bedsides of their dying parents, these two do not have any kind of innate sense of what to do. The moment defies the natural order. Where is the innate response of action in a parent whose child is dying? Perhaps there is none.

The nurse guides them. Tells them that he can hear them. Can he? Regardless, it is better for everyone if we believe it is so. She tells them to take his hands if they wish. They do. The father falls to his knees and sobs. The mother collapses into a chair that the nurse slides beneath her. I cannot look at the father without beginning to cry. I look straight back into the eyes of Mr. L, which look straight back at me. I grow increasingly convinced of his absence behind his gaze—otherwise why would he fix it on me? Why, with his parents beside him, with a doctor beside me? Nonetheless, I try to smile a comforting smile, in case he can see as well as hear. I try to convey to him peace. I expect that I am not particularly convincing, though in the moment I believe that I can be. But I do not feel peace inside. What I feel is emotion, and then a sense that I am not entitled to the emotion. I feel sadness, yet who am I to feel sadness when I am in the presence of parents watching their son die? I feel fear, yet how could it compare to the fear of this young man, taking labored breaths that propel him toward death’s uncertainty? I wish him to live, but I am sure that is only to relieve my own discomfort, and, if Mr. L’s living will is any indication, it is not necessarily what he desires. As minutes pass and his breathing seems to grow more and more pained, as his parents seem less and less sure what they should be saying, which breath will be his last, I begin to wish he would die. To end this fraught stretch. I do not know if it is a selfish wish. It is an interminable time. I wish the scattered, fractured breaths would cease, because we all know that they will.

And then they do. Though there have been several times when twenty, thirty, sixty seconds passed between desperate breaths, this time each of those segments pass, once, twice, and there are no more breaths forthcoming. I cannot tell if his parents notice. Then his father says, “He isn’t breathing anymore, but…” and points to his son’s abdomen, where the aorta is still pulsing, a sign that the heart is futilely pumping, refusing to cease. We expect it to cease momentarily, because, like any muscle, it will run out of oxygen, too.

I do not know how many minutes pass, but several. Perhaps four. Perhaps five. The father asks the nurse to close his son’s eyes. She does. Another moment passes. And then, as if we are in a horrible movie, there is a long, loud gasp from Mr. L. I am so surprised that I jump. There is another. And another. And then they come more regularly. And he still looks lifeless and gray, but he is clearly, inexplicably alive. When, after ten or twelve minutes of breathing, it becomes obvious that Mr. L will breathe on his own again for at least a short while, the doctor and nurse explain this to the parents and then leave the room, and I follow them.

The nurse says in thirty years of caring for the dying, she has never seen anything like it. The doctor says one time: She left an elderly, demented man who she thought had just died after telling the nurse she was going to call his wife and have her come in. She says the man began to breathe again, and the moment his wife arrived and held his hand, he died for good.

Was Mr. L alive, dead, then alive? Was he dead until his breath resumed? What did I see him experience? I was not there when he took his final breath, but did I see him die?

During my first semester of medical school, I cannot know how the emotional difficulty of the actions we perform on our cadavers will help us prepare for the agonizing moments we will observe in the lives of the living. Nonetheless it is a welcome shift away from this intensity when the pelvic hemisection is complete and we move on to other dissections in lab.

The afternoon following the hemisection, we are to roll Eve over, dissect the deep muscles of the back and chip open vertebrae, with a chisel to look at the spinal cord. Now that Eve’s left leg is detached, turning her body is significantly easier. While Tripler and Raj take the whole afternoon to snip at the vertebrae first with heavy-duty toothed shears called ronguers and then literally use a chisel to break into each whorled vertebral body, Tamara reviews cross sections, and I spend my whole day “cleaning up” the deep pelvis.

It is inevitable that when Dale or Dr. Goslow come over to answer a question, somewhere in their response will be “so just clean this up a little more….” No matter whether we are looking to locate a structure, trace its path, find branches or innervation, or even understand its functionality, there is always more isolating to be done. There is rarely time built into the syllabus for this kind of detail, so when the assigned dissection is one that cannot be manned by everyone at the table, it is a good opportunity to tend to a previous dissection.

Clearing away fascia from structures takes patience, and the fascia clears away differently in different places. Its consistency—and hence its tenacity—varies. Under the skin it is webby and soft, and you can push through it with your flattened hand or a finger inserted between muscles. In areas of fat, it is also soft, but thick; using rat-tooth forceps, you can “pick” it away if it is in globules. If it is less dense, a whole area will fade into one clingy strand, much as a spiderweb does when you grab it with a broom. Clearing this kind of fascia makes a sound like peeling a slightly green banana. It is quiet, and one of the parts of anatomy I find most satisfying. Progress is clear, and you don’t have to battle; each movement is an act of revealing—the thick belly of a gray-brown muscle, the shiny white of tendon, the gloss of smooth muscle in an organ. You slide your hand beneath one of the four quadriceps and you can isolate it from its partners, hold it by itself, your hand wrapping under and circling all the way around it. You can slide your hand up to the point on the pelvis or femur where it begins and down to some slim tendon where it ends, and you can easily imagine that if the space between the two ends shortens, then the knee has no choice but to kick out, just as it does in reflex tests in the doctor’s office.

Other areas of fascia are tedious. The thick aponeurosis of the palm is replicated on the sole of the foot, and it is very slow going in both spots. The connective tissue is tough and irregular, as one would expect from the functions of these all-important areas. In these regions I am impatient and use a scalpel to clear despite suggestions not to. I am sometimes left at the end of the day without a small nerve or artery, having “blown through it,” as Dale would say. The texture of this fascia is tough and stringy, like the mesh coating of a scrubbing dish sponge invested with fat where the sponge would be, occasionally harboring vessels and nerves.

By the afternoon’s end, I have separated out most structures of importance inside the pelvis, having cleared (and thrown) away tangles of vein. We can see clearly how the common iliac artery branches into the internal and external arteries and gives off blood supply to the uterus, rectum, bladder, even through the pelvis to the gluteus muscles and one muscle of the thigh. We can pull on the inferior gluteal artery and nerve and see them tug on the gluteus maximus muscle on the other side of the pelvis. More than anything it is exhilarating to me how much the afternoon and the search for branches among the mess helps me learn what is what and what is where.

I do not pay much attention to the spine dissection until Tripler and Raj are through. I can, after all, easily roll the leg around whichever way I want the pelvis to be oriented now that it is disconnected from the upper body on which they are working. They are tired. An afternoon’s work has given them just a three-inch window of the spinal cord, covered by a cloak of dura mater, a tough, membranous coating, translated literally as “tough mother,” which protects the brain and the length of the spinal cord. The cord itself is unimpressive, given its extraordinary function. Eve’s is dark brown and about the diameter of my pinkie, dull in comparison to the sciatic nerve, which shoots out of the pelvis and down the leg and is the size of a sturdy rope and a gorgeous, glistening off-white. The colors of the spinal cords vary from cadaver to cadaver, as they do with all tissues in all structures. A rather incredible look at a dorsal root ganglion has emerged, however, complete with roots and rami, over which you can trace the path that sensory impulses would take to the central nervous system from the rest of the body. It is tiny and perfect and replicated on each side at each vertebra. Crazy.

At the end of this lab, Dr. Goslow holds a question-and-answer session, as the second exam is only days away. We all sit by our cadavers. I clean off little pieces of fat from the body and clear away obscured portions of muscle as I listen. This process that just weeks ago kept me from falling asleep at night is now something I do to occupy myself, strangely satisfying.