chapter twelve

Dismantled

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

RAYMOND CARVER, “LATE FRAGMENT”

As the semester wears on into its final month, subtle changes in ability and perception occur in my classmates and me. Sometimes we notice them, such as when we dissect the leg and its structural similarity to the arm makes us laugh at how tentative our first cuts through the skin and fascia of the arm were, how befuddled we were by uncovering the musculature we expose so easily in the lower limb. Other times the change is a more whole and therefore less perceptible one, as when you are twenty and someone perfectly describes certain yellow orchid blossoms as miniature ball gowns, and it becomes impossible to remember ever looking at them without seeing the full skirt, the cinched waist. Eventually the thick elasticity of artery and the sheen of tendon are second nature to us. We cannot imagine not knowing that it is the pulse of the descending aorta that visibly beats in the thin woman’s belly, the bony zygomatic arch that forms the cheekbone’s rise.

And from the moment when anatomical knowledge begins to take on that quality of the innately known—at some unidentifiable point midway through the semester—the foundation is laid for an understanding of disease, and then a basis from which we can counteract the disease. In this way our dismantling of the body gives birth to our ability to make the sick and broken body whole.

Dr. Goslow takes advantage of this shift and tries to make us feel more settled in our new point of view. One day, in order to lighten things up in a lecture on gait, he shows us clips of Hollywood movies in order to discuss the topic. The movies are a perfect learning tool, liberating us all from memorizing isolated facts and reminding us that the big picture of anatomy is that the structures all actually work together. He turns down the lights and lowers the screen. A terrified woman in a knee-length skirt and matching suit jacket is running through city streets, looking back over her shoulder at someone unseen, chasing her. The next series of frames sends us into gales of laughter, as we learn that it is King Kong in pursuit, thumping along in his own earth-shaking run. Dr. Goslow stops the tape, turns up the lights, and jumps up on a table in the front of the lecture hall.

“Okay, you guys, so we all know we run like this,” and he makes the motions of running, leaning forward slightly but quite upright, pumping his arms and legs in a forward plane. “But Kong and his fellow primates, they’ve got an entirely different center of gravity.” In a startlingly good impression of the primate body habitus, Goslow spreads his feet wide, toes turned out and knees bent, and hunches his shoulders. He ambles across the table, arms dangling, body low and squat. The room roars. Our distinguished professor makes a terrific gorilla. “Do you see the difference?” he asks. “Gorillas have a huge upper body, I mean HUGE, in comparison to us, so their weight is shifted, and therefore their gait is totally different than ours. All right.”

The lights dim again, and Frances McDormand comes up on the screen in Fargo. She is rosy-cheeked in a bleak, snowy field with a dark blue police uniform and hat on, and she is easily eight months pregnant. As she trudges through the snow, she spreads her feet wide, and leans back, her hand on her lumbar spine. The clips continue: Jack Lemmon and Marilyn Monroe are both walking in heels in Some Like It Hot, leading to a discussion of gendered differences in weight distribution; a group of sailors belowdecks listening to the creepy thud of Ahab’s wooden leg in Moby-Dick are used to demonstrate how the rhythm of gait is altered when there is no give in the ankle or knee. “Hunchback” Igor shows us the walk necessitated by a bent spine in Young Frankenstein; a young girl who suffered from polio wends her way with arm braces and outwardly curved legs in The Little Girl Who Stole the Sun. Finally, Kevin Spacey as “Verbal” Kint in The Usual Suspects leaves the prison office where he has been held and shifts from the palsied, stroke-induced gait of his alibi persona into a completely normal stride. The whole lesson is perfect, both in tone and in effectiveness. We have the images of these walks etched in our minds, via lightness and laughter.

In lab, as my classmates and I make our ways further and further through the remaining regions of our cadavers, the bodies begin to look less and less human. With fewer areas covered by skin, body cavities opened and emptied, and flayed muscles disrupting the familiar outlines of the limbs, it is sometimes difficult to tell from afar which body part each table is dissecting. It is during this stage that my parents come to town for a visit. I invite them to come into the anatomy lab if they like, to see the work that I have been doing, what a heart looks like, or a lung. My father endured the loss of his own mother at a young age. As a result, perhaps, death is particularly resonant for him and mortality a great fear. He chooses to come with us to the medical school but wants no part of the cadaver viewing. My mother, on the other hand, matter-of-fact and not at all squeamish, enters the lab with me and, unfazed, promptly states that the bodies look a lot like turkey carcasses.

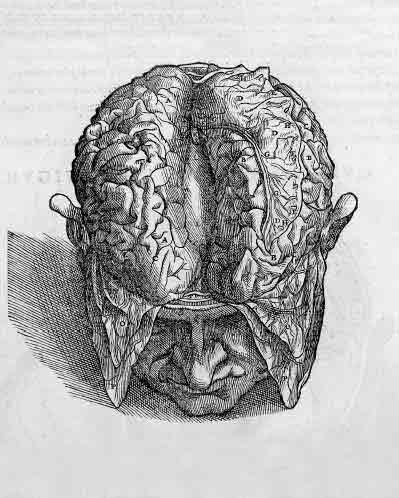

When Raj, Tamara, Trip, and I have finished a rather quick dissection of the leg, only Eve’s head and neck remain to open and explore. The head dissection gathers together many of the questions upon which the experience of gross anatomy has forced me to reflect. The brain is the true embodiment of my own conflicted response to anatomy. Somewhere deep within its crenellations, here lies wonder, and here lies the question of whether we have a right to pursue wonder in seemingly inhuman ways. Here is the knowledge gained by dissection, which drives our actions forward, and here lies the toll the process takes on each of us, in stress or dreams or dissonance. Here in the brain is the newly transformed identity of the doctor-to-be, with a beginner’s knowledge of disease and healing, with a stomach more steeled to trauma and to death. But somewhere, too, there must be the echo of the person who existed before cutting a human body, before feeling the cool stiffness of a pulseless heart.

The brain—the mind—is the manifestation of the liminal spaces into which doctors plunge. It is where personhood resides, of ourselves and our loved ones, of silent Mr. C in the ICU and, though undeniably quiescent, of Eve. The brain is what we as doctors fight to save, whether we are nephrologists or orthopedic surgeons, psychiatrists or dermatologists. We are trying to heal and preserve personhood, which can reside nowhere else. Still, in the midst of all these truths, the answer to how I feel about myself now as a dissector is not eminently clear.

Perhaps in a shared acknowledgment that this fact is collectively true, the entire room quiets when the face dissections begin. We have all now removed the plastic bags tied around our cadavers’ hands and feet, and though they are mostly replaced in order to keep the flayed structures in the fingers, toes, palms, and soles from drying, the mystery of what lies beneath these bags is totally gone. The bags over the heads, however, are a different matter. No group, including us, has spoken of their cadaver’s face, so I have no way of knowing whether any of the other groups have done what Tripler and I did on the first day, whether anyone else untied the cord around the neck, lifted the head to pull away the plastic bag, unwrapped the gauze to look at the face.

Initially I take the quiet in the room to signify that no one has seen the face of his or her cadaver, that this odd unveiling is new to everyone but us. Then I realize that we, too, are quiet. This moment has no less power for us, despite the fact that we have seen Eve’s face once before. Throughout the room lengths of gauze are being unwound and shorn heads and faces surfacing. What strangeness. The mix of reactions is inexplicable. How are you supposed to feel the moment you first see the face of a person whose body you have cut into, cut apart? A body whose interior you know more completely than your own or that of any loved one? Certainly we feel different about Eve now than we did that first night in the darkened lab. Her beautiful dead face is the same—mouth slightly open, eyes slightly closed. Only now her face seems to float above a dismantled body. The context is altered. She has become more and more like some dark, strange work of visionary art: opened chest, emptied belly, leg cut through and rolled to the side. And she is Eve now; large-stomached, gallbladderless, slight-framed Eve. It is strange to think that I feel I have come to know this woman. I’ve seen her daily, touched her, cared for her, been pushed and angered by her, dreamed about her, but know her? I know her body, yet in a manner that a psychoanalyst would love: Any emotion, any perceived relationship, any tenderness or fear or repulsion or frustration, any humanness is my own and only my own. She knows me from no one. She knows nothing. Anything beyond the physical is my own construction. I do not even know her name.

And yet when I look at her face, I think, Yes, that’s Eve, but now less so than before. Because if I have been witness to anything in her life, it has been this final change, where even the physical evidence of her life, left long ago by any spirit, now resembles her less and less. And it is hard to know just how big or small a role our dissection plays in that process.

One November I flew west to be with a dear friend at the funeral of her twenty-four-year-old brother who had hanged himself in their parents’ basement. Even in the casket, days after he had died, he had the beauty everything young does, and it was that beauty that struck the chord of most powerful dissonance. Amid lilies and vaulted ceilings and song, here was his lovely face that dared anyone to say, Better off or It was his time. But even with that beauty, even with his hands that were identical to my friend’s, even then he resembled himself less and less. From the calling where I said—and meant—my first Hail Marys to the moment just before the casket closed when I was seated in the church and from behind me heard my friend wail as if she had just found him hanging, already he was further gone.

I think of the Jewish sense of what happens after death, that we live on only inasmuch as we are kept in the memories of the living. And if we have the chance, the totality of our memories of people includes how they are with us after they are dead. My friend’s brother was less himself over the course of our days of mourning because our sense of his living self as something with us lessened. He is, of course, kept well in our memories, but kept differently now. The fact of his death intercedes. I never remember him as the living person he was. He is locked at twenty-four or younger, tainted by tragedy, past rather than promise.

And this is not unlike the shift that has occurred for me the second time I see Eve’s face. I recognize her, know it to be her, but know, too, that the changes I have witnessed—caused—in her are irreversible ones. That she will be kept differently in my memory. And as my friend cried out at the moment when the casket was just about to close, I understand that even these moments of reference are tenuous. In the next days, I will peel away the skin of Eve’s face. I will open her skull. I will render her unrecognizable. More than any other part of her body I have altered, her face, as it is for all of us, is her identity, and I will remove it. This—the first chance for many to look at the faces of their cadavers—is the last chance for us to look at the faces of our cadavers.

I wonder, then, what this brief moment feels like for those who have not looked beneath the gauze until now. Are they surprised? Does the face seem to fit? Does the group with the muscle-bound, tattooed cadaver think his face is smaller and sweeter than they would have thought? Does the face of the woman with lavender fingernails have jagged teeth—or no teeth? I suspect there are those who look at the face only as quickly as they can, or not at all, other than to perform the dissection. Though no one admits to it, I suspect there are those for whom the face is too real to focus on, too human.

But for most of us, when we have finished looking at the faces of our own cadavers, there is a kind of furtive glancing to see what other faces look like. We think there will be a power in this—that we will be moved by the emerging individuality of the cadavers—but the truth is, there is not. Partially this is due to the fact that, like the breathless bodies when we first saw them in their bags, the faces of these people do not look like faces of living people. The color is wrong. Their eyes are half shut, or one eye is closed more than the other. As was true with the first cadaver I ever saw, some of the faces have flattened cheeks or noses—postmortem alterations that make it impossible to picture what their faces were like in life. Their faces are, in shape and color and expression, like no living person’s face. Partially, too, the lack of resonance in the viewing of the faces is the result of the androgynous appearance that is unpredictably but universally lent to the cadavers by their shorn heads.

During the below-the-neck dissections, when we would study cadavers other than our own, we consistently used gendered pronouns in our conversation. “Does he have a good spinal accessory nerve?” or “Her subclavicular takes this crazy turn.” In what proves to be one of the more paradoxical realities of the semester, people increasingly misidentify the gender of other cadavers after the heads are uncovered. This is perhaps less surprising once facial dissections are performed, but even when the faces are intact, the shaved heads and un-made-up faces are, for the most part, gender neutral. Even Eve, so feminine in the fineness of her features, is frequently referred to as “he” by approaching classmates. “Can I see his digastric muscle?” they say, and we cringe.

“Her,” we say.

“Sorry,” they reply. “Can I see it?” Inevitably, we make the same mistake at other tables on other bodies. Without even realizing it, some of my classmates begin referring to individual bodies in the genderless, if plural, “they.” As in, “Do they still have an intact phrenic nerve?” Something lessens.

The night before the head and neck dissections begin, another dream: I am at my desk, holding Eve’s brain in my hands. I have two or three atlases spread out before me and am locating various divisions and compartments of the brain. Caudate. Putamen. Corpus callosum. Septum pellucidum. Fornix. Anterior and posterior horns of the lateral ventricles. I race through them over and over again, growing increasingly distressed. Lateral sulcus. Genu of the corpus callosum. Lentiform nucleus. Infundibular recess of the third ventricle. I am missing something. I frantically turn pages, look at diagrams, read charts, look again at the brain.

I cannot find her memories.

At this stage in the semester, our Dissectors have become disgusting. Each time Tripler has to consult the book for its instructions, she grimaces. “Most foul,” she groans. Days on end of gloved hands covered in formalin and the grease of fat, with the odd clinging particle of dried brown blood or unidentifiable tissue, have flipped through pages and rendered them nastily translucent and endlessly damp. The Dissector’s instructions sounds as if they are for something as banal as a cobbler recipe. “We will begin the dissection of the head and neck region by exploring the muscular and visceral components of the neck first. Then we will proceed onto the face, remove the brain, study the orbital region, and then work our way systematically down through the head toward the deep structures of the neck.”

“Oh, noooooooo,” Trip wails, and I share her sentiment. We know better than to trust the facile tone of the text. “As if we can just—poof!—remove the brain,” she says. “And by ‘study the orbital region’ I doubt they mean just lean over and look closely.” We both give a kind of defeated laugh, knowing that she is right and that it doesn’t matter. That we will open Eve’s skull and remove her brain, dissect her eye and socket, and “work our way systematically down through the head toward the deep structures of the neck,” whatever surely ominous path that implies.

We make a series of cuts, starting with the scalpel behind Eve’s right ear, guiding it down to her jawbone and along the edge of her jawline to her chin, then continuing, to make the same cut on the other side, finishing behind her left ear. The bone is just beneath the surface, so the splitting of the skin is visible only if you look closely. The skin now has a kind of reverse seam, two new edges. The other cut is perpendicular, beginning at the chin and sliding down the center of Eve’s throat, ending where, on the first day, we peeled away the skin across her clavicles. As we did with the skin on her chest, we grasp the corners of skin we have made at her chin (how inherently unlike skin to have edges, corners) with the rat-tooth forceps. Using the scalpel, we cut away the connective tissue beneath, little by little. The skin peels back, revealing the crowding of muscles in the human neck.

Because the neck lacks the bony protection conferred by a rib cage or a pelvis, for example, many of its structures can be seen or felt on our own, living bodies. The most easily identifiable muscle in the neck is the sternocleidomastoid. The name sounds prehistoric and powerful, but in reality it merely describes the bones connected by the muscle’s fibers. The sternocleidomastoid originates on the mastoid process of the skull, the bony prominence you can feel immediately behind your ears, and attaches on both the sternum and the clavicle. The muscle is clearly visible on a slender-necked person and can be quite prominent when the head is turned. In order to feel the tendon, we each return to our own jugular notch, which was our original landmark on Eve before we made the first cut across her sternum. We raise our fingers again to the very bases of our throats and find the notch in the bone. If, with your index finger in the notch, you then turn your head so that you are looking over your right shoulder, you will feel that your finger is now held between the bony notch and the tendon of your left sternocleidomastoid. You can grab onto the tendon and follow its course up the side of the neck, feeling the belly of the muscle. The muscle becomes even more prominent when flexed. To feel this, again look over your right shoulder, fingers along the sternocleidomastoid, and then, keeping your neck twisted to look over the right shoulder, tilt your head so that your left ear is parallel with the ground. The tendon goes taut, and the muscle is easily palpable.

Because the face and head dissections are the final ones of the class, I think we are all surprised by the extent of the reactions we have to them. Lex, heretofore a stalwart mix of studiousness and piercingly smart humor, leaves the room in a rush. He explains to me later in a quiet tone that he had a panic attack; he felt his heart would pound out of his chest; he felt he could not breathe. Despite the inertia of the dead, they actively affect us. Even now, as the term winds to a close.

There is, of course, an opposing argument. Lex’s panic does not stem from his cadaver; she has, of course, done nothing differently today than every other day he has come to her side. Rather the fear comes from the fact that he is in a room full of otherwise relatively normal people, his friends, his colleagues, and we are all engaged in taking the faces off dead human beings. Some cut through lips with scalpels. Others pull off masks of skin so they are holding in their hands the obvious oval of nostrils, whiskered cheeks, eyebrows. When they are not cutting, they talk to one another, consult their textbooks, and as they do so, their hands rest on a dead man’s chin, their forceps sit across his forehead. And how much easier for me to write of the things “they” do. As if my thumb does not come to rest on Eve’s eye socket or lips or teeth when I am trying to identify the muscles with which she used to chew.

The upsetting nature of these dissections resonates even more deeply with me because they occur as my grandmother recovers from her stroke and as my grandfather begins to die. My grandmother has filled a space in my life that no one else possibly could have. She is, above all else, a truth teller. She is the kind of woman who cannot see the point of beating around the bush, who does not understand how talking around something could possibly be any more effective than saying things the way they are. She is rare in this way as a person and even more rare as a woman, and there is something deep inside me that responds to her whenever I am near her and says, “Yes, yes.”

Unlike me, she is not at all sentimental. Deborah loves the story of when I asked her for the meaning behind my names. My first and middle names were names she had chosen as middle names for my mother’s two sisters, so I was anxious to hear from her how she had chosen their names, which then became mine.

“Well,” she said, “I always wanted to name a daughter Christine, but when the neighbors at Higgins Lake beat me to it, I certainly didn’t want to do the same thing they had done, so I just kept it as a middle name. As for Elaine, I guess by the time I threw out all the names of people I didn’t like, that was pretty much what was left over.” Though it wasn’t the emotion-laden story I might have hoped for, I knew it was honest, and so, crestfallen as I was at that moment, I have come to love the story, too. It represents her perfectly.

She was the college freshman at Michigan who danced with an older sorority sister’s date at the pledge formal and hence landed my all-American basketball player, law student, hotshot catch of a grandfather. (He would always tell the story of how he came to pick her up one Saturday evening for one of their first dates, only to find her coming home from an afternoon picnic with another beau. She, unapologetic, said good-bye to the afternoon date, ran upstairs to her room to brush her hair, and came back down, ready for an evening with my grandfather.)

In my childhood she was the grandmother to whom you brought your bluegills when you caught them in her pond. She would take out the hook for you, whack them on the head with a stone, fillet them in the laundry room, and then cook them for that night’s dinner alongside fresh Indiana sweet corn and garden asparagus. So it was through her that I first learned about death—about the birds that got tangled in the nets around the blueberry bushes, about the snakes that got hacked in half with her spade, eventually about the emotional fatigue of aging: “It’s a damn shame when every single one of your best friends is dead,” she would sigh. And if she said it was, I knew it must be true, though it was—and remains—nothing I could imagine.

During World War II, Grandpa was playing semipro basketball and practicing law, and so he got sent to Texas to be in the Judge Advocate General program instead of to more dangerous places. That left Grandma in Indianapolis, a woman in her early twenties, living in the house next to her in-laws, with four children under the age of four. Never a woman to want too much input from someone else, Grandma tired quickly of this arrangement and packed herself and all four kids into the car, driving the eight-plus-hour drive to Michigan, to Higgins Lake. Once there, she lived with the children in a cabin with no heat or electricity or running water. She heated bathwater over a kerosene flame and washed diapers out in the lake, and she preferred the situation mightily to the one she had left.

“What a dumb thing to do,” she would say of her time alone at the lake with the kids, looking back years later. Of her mother-in-law, she would claim, “I’m sure she said one little thing I took offense to, and it got my goat, and without giving it any thought, I just decided that was that,” but her smile as she said it always made me understand that she knew exactly why she had done what she had done and would do it all over again the same way. The four children, the packed car, the lake, broad and dark when the sun went down, crickets and tree frogs singing through the screen door, through the starry clarity of Michigan nighttime.

A grandmotherly figure she was not, but a figure bigger than the room, a figure you couldn’t help but fall in love with, couldn’t help but want to be.

The story of her life with my grandfather is, above all, a love story. From the pledge formal, to their dating days in Ann Arbor, to their raising four children together and eventually growing old together, their devotion to one another was plain, as was their steadfast belief that they had each scored big in landing the person everyone else wanted to catch. Photos of my grandparents at various stages of life are all ravishing and depict a life that ranges seamlessly from daily midwesterndom to worldly glamour. At a bridal shower for my mother, my grandma is stunning in a yellow sixties minidress and white hoop earrings. My parents’ wedding was at my grandparents’ Mooresville, Indiana, home, and my grandfather looks regal in his tuxedo and perfectly combed hair, welcoming guests onto the porch for cocktails before dinner, to look at the sculpted ice swan and listen to music from a brass band. In another shot he and my grandmother are beaming and tanned on a deep-sea fishing boat in the Caribbean, holding a huge, shimmering tuna between them. At their fiftieth anniversary party on my uncle’s porch, my grandfather diligently looks at the camera and smiles, while beside him my grandmother nearly cackles with laughter, looking just past the photographer at something no one can now remember.

In my favorite series from 1941, my nineteen-year-old grandmother and twenty-three-year-old grandfather are at Higgins Lake, he in a dark pin-striped suit and diagonally striped tie and she in a polka-dotted shirtwaist dress with a knee-length pleated skirt and fabulous white-and-black spectator pumps. World War II has begun, and they’ve married quickly, before my grandfather has to leave for JAG duty. The family lake cottage will be their honeymoon retreat. They are seated in one picture and holding hands, both gorgeous, with the openmouthed grins of newlywed disbelief. My grandmother looks as if she will break into a gale of laughter at any moment. In another shot they mock solemnity, my grandfather seated with his hand over his heart and my grandma standing beside him, one hand on his shoulder, one gripping a clump of wildflowers. Neither of them smiles. In a third, a commentary on the speed of the wedding, my grandmother’s parents have orchestrated a hilarious scene. My young great-grandfather holds a shotgun and looks purposefully at the couple. My grandmother has a towel tied to the back of her head with a belt and holds a bouquet of cattails. Beside her my grandfather takes a swig from an old whiskey bottle. My great-grandmother, barefoot, buries her face in a dish towel, weeping. A family friend holds open a dog-eared Bible and wears a neck brace meant to resemble a religious collar. Each of their expressions is pure seriousness. I can only imagine how many shots were ruined by laughter. Knowing what I know, it is nearly impossible to look at the faces of my grandparents in these pictures for what they are—near children, in a moment of pure joy, unaware of the expansive family they will begin raising a year from then, of the sixty-year relationship into which they have just entered.

It has been clear, always, as one of those things that every family member knows but may never discuss, that my grandmother might survive many years should my grandfather predecease her but that the inverse could not possibly be true. In the years before I enter medical school, my grandfather has increasingly faced the battles of aging: breaking hips, losing his breath to worsening congestive heart failure, harboring the cool, weak-pulsed feet that are harbingers of failing circulation in his legs. His health has been diminishing in seemingly unrelated ways that add up, even knowing what I know now, to no diagnosis other than advancing age.

Once, having raced to Higgins Lake after my grandfather fell off the metal dock and into the shallow water in an attempt to step into a boat to go fishing, I sat with my grandmother in his hospital room, waiting for Grandpa to be rolled off to hip-replacement surgery. When the surgical transport team came, unlocked the brake on his bed, and began to wheel him away, Grandpa looked tearfully up at my grandmother and said, “Didn’t we always have fun with our Sanka after dinner?” He would survive the surgery and, despite his abysmally low motivation for rehabilitation of any kind, would survive many years beyond it. But that moment remained with me, a vision of the patriarch afraid, who, when pressed to define what was meaningful to him over the course of his life, looked to the woman he had loved so long and spoke of their nightly routine of ten or fifteen minutes of decaf and conversation. The wisdom of that moment of pure emotion resonates with me still: that the dearest and most enduring moments of our lives are sometimes the quietest ones.

The summer before I began medical school, just before my grandmother had her stroke, my grandfather awoke in the middle of the night with a cold and painful leg. He displayed the symptoms that I would later learn clearly indicate femoral arterial occlusion. A hospital evaluation did not take long to determine that my grandfather needed surgical intervention. The pain was caused by early necrosis. A lack of blood flow to the tissue meant that beyond the blockage the leg was receiving no oxygen. Without oxygen the tissue was beginning to die.

My grandfather underwent surgical bypass, grafting a vein to his femoral artery above the site of the arterial blockage and reconnecting it below, thereby providing an alternative route for oxygenated blood to reach his lower extremity. The surgical wound, by necessity from harvesting the vein and accessing the artery for the bypass procedure, was massive, stretching from his groin to below his knee. Thankfully, his fragile body tolerated the stress of surgery and anesthesia, but, to my grandfather’s chagrin, he was sent to a nursing home following the surgery for rehab therapy and skilled nursing before he could be sent home.

When, therefore, his wife of nearly sixty years had a stroke and was hospitalized, my grandfather was in his own state of recovery. And because, in her rare moments of awakening, my much-changed grandmother asked clearly and repeatedly to see her husband, my grandfather received special permission from his geriatrician to be driven to the hospital and wheeled in a chair to my grandmother’s bedside.

My mother and I had grave concerns about how my grandfather would handle the sight of my previously strong and out-loud grandma in her current condition, bedbound and only intermittently lucid. My first sight of her after her stroke had racked me, and I had had to take hold of the hospital bed frame to smile at her and remain standing.

A journal entry from those first days:

She is able to speak and is totally lucid, with the exception of moments in between sleep and wake. The second or third day, she told me a little boy had found pieces of her eye, and now they were at the fire department. A few days ago, she woke up thinking she owed money to a bunch of people on an airplane. Yesterday she at least knew it was a dream—but stayed stuck in it awhile, looking alarmed—and had been dreaming of “spare parts”—I think prostheses—that “didn’t fit” and were “like lobster claws.” Shortly after that, though, she regained some motion in her left leg (though continued to bemoan the “left arm not worth a damn”). What a week. It was simultaneously ugly and wrenching, but with these moments of small progress that were somehow now relatively wonderful and important. The first few days were very tough. I arrived to see her with oxygen in her nose and eventually a feeding tube in her nose also, which was excruciating to put in and which she pulled out in her sleep one night. Then she had an abdominal tube put in, through which she was fed a Slimfast-looking bag of stuff laced with a tincture of opium to try to stop her diarrhea. I had to adjust to an extremely weakened Grandma, who spoke rarely and softly, slept all but five or ten minutes an hour, opened her eyes only barely and only if asked to, and flopped around lifelessly as nurses rolled her, pulled her on and off her bed and gurneys, etc. The first few days, she would be so exhausted that she would sleep—even snore—through nurses turning her body, starting IVs, giving her shots in her belly, pulling her onto a gurney, wheeling her on and off of elevators, and she wasn’t even medicated heavily.

We first tried to gently suggest to my grandmother that she wait to regain a bit of her strength before she had a visit from my grandfather. Wouldn’t she rather wait until she could be assured of staying awake while he was there? But she asked for little during those days, and her request for him was consistent. Eventually we realized we could not guarantee that she would be any better a vision for him to see days, or even weeks, from then. Even more importantly, we knew that she had undergone this substantial loss, was afraid, was having terrible dreams that disoriented her, had no idea of what the future might hold, and wanted her husband. It was such an obvious desire.

My mother, who had kindly tried to shield Grandpa from some of the severity of Grandma’s condition, fearing that it would slide him in to a deep depression that could be a blow he might not recover from, began to prepare him for what he would see when he saw his wife. She also tried to explain to him that Grandma’s state was tenuous and that it would be important for her that he not have too severe a reaction, which could discourage or upset her. Grandpa, consistent with his nature surrounding difficult conversations, was mostly quiet on the subject. In her characteristic thoroughness under such circumstances, my mother consulted with a social worker friend who specialized in geriatric issues. The advice she received was simple but good. Keep the visit relatively short, and then take your father to ice cream afterward. Keep conversation light, but try to get him to talk a little bit about his feelings after having seen her. We had no idea what to expect, but it would be dishonest to say that we did not fear a mutual collapse.

As it turned out, I could never have predicted what actually transpired. I left Grandma’s room to meet my mother and Grandpa when they arrived. He appeared solemn and nervous, his postoperative leg heavily bandaged and his tall, athletic frame crunched into a wheelchair. We rode in the elevator up to Grandma’s floor, and my mother and I made small talk in the elevator about the tiny but encouraging bits of physical progress she had shown that morning. A bit of movement in the left leg. Slightly longer periods of wakefulness. Grandpa said nothing and looked straight ahead at the elevator doors. When we reached the ward, I walked quickly ahead to tell Grandma that they had arrived and to make sure she was awake and as presentable as possible. She was a little tearful.

Suddenly we heard a booming voice outside the door, coming down the corridor. “Is this the room of Mary Townsend? Magnificent wife of John Townsend? I’m looking for Mary. Is this where I can find my love?” We looked to the doorway, and in came Grandpa, wheeled in by Mom and gesticulating dramatically. In a moment for which I will always love him, at first sight of her he registered nothing like sadness or disappointment or fear. Instead he looked squarely at her and said, “There is my Mary. Mary, you look so beautiful! I’ve never seen you more beautiful in all my life.” I, on the other hand, had never seen such an outpouring of emotion from my normally reserved grandfather, and he was nowhere near done. Both of them in tears, he took her hand in his and began to talk to her about the picnics they used to have in the arboretum in Ann Arbor, where they would lie on a blanket and kiss. He asked my mother and me to help him stand, so he could lean over the rail of the hospital bed and give his wife a kiss. He began to sing, in a full voice, a song to her about the wind in her hair. In so many ways, the scene was implausible: My grandmother was, at that time, a fragment of her former self, exhausted, sick, with plastic tubing in her nose and side and IVs in her arms, and my grandfather was as vociferous as I had ever heard him about her beauty and allure. It was, without question, the most perfect thing he could ever have done for the woman he loved, and it will remain, I suspect, the image that defines the depth of true love for me for the duration of my life.

Over the course of the fall, my grandmother’s health slowly improved and my grandfather’s health gradually declined. I was aware that my own personal grappling with the body’s ability to heal and to fail colored the ways in which I approached my medical studies. At school during the day, the minutiae of histological slides and physiological equations seemed too far removed from the medical treatment of real people. At night, during phone conversations with my parents or grandparents, I felt the full thrust of how illness affects people’s lives, but I was not yet equipped with any of the knowledge to help assuage it. The result felt cruel and misdirected, like learning the alphabet and numbers in a foreign language, when you just want to know how to ask for the bathroom.

Rationally, of course, I knew that the first year of medical school was a necessary foundation for clinical knowledge. And similarly I knew that even as I would acquire a broader and deeper understanding of medical treatments in the years to come, there was nothing that I could do differently from what my grandparents’ fully trained doctors were doing. None of us knew the cure for aging. None of us could prescribe medication to return an elderly couple to the sepia-toned photograph in my living room of barely twenty-year-old newlyweds, holding hands in a lake cottage and laughing at whatever the future might throw their way.

Still, the anatomy lab was a tangible space in which the specter of my loved ones’ mortality swirled. For all the time spent wondering what was going on in their sick bodies, I could look into Eve and attempt to localize their bodily failings. The dissection of the head would have already held this potency for me, due to the fact that a clot of one of the brain’s vessels had taken the use of my grandmother’s left side, along with an unlikely collection of numerically oriented skills. She could no longer tell time. Even looking at a digital clock, she did not always know the time of day. She could not play cards. She called my mother endlessly, complaining of the channel numbers on her TV being changed, of her VCR remote control not working. I wanted to see the vessel, named by her doctors and identified on CT scans and MRIs, whose blood supply momentarily ceased, blackening a section of her brain.

Less easy to locate, less easy even to attribute causality to, was my grandfather’s physical and mental deterioration during this time. I could follow on Eve’s leg the exact vessel in the leg that had failed him and the vein that had been used to bypass its path. I knew the tract of the wound along his leg, and, when it failed to heal, I knew the line the orthopedic surgeon must have used for the amputation. But in what locatable space was the reason the tissue did not heal? I could find the vessel that occluded and brought my grandmother into this shifted and foreign existence, but which section of the brain explained these new moments of delusional fear in my previously steady grandfather when he thinks that my grandmother is having an affair with his nurse, when he thinks that the IRS has taken his remaining leg?

I am thinking about the brain, the look and feel of it. I am thinking about how the heart was at first mysterious to me, but then I could name its spaces, chart the flow of blood through it, fill it with water and watch its valves expand and catch. I learned the physiological formulas that described the electrical impulses in cardiac muscle, which could account for its incessant beating, for the life-sustaining propulsion of blood. I think of the lung and its branching network of exchange, oxygen for carbon dioxide, new for old; the kidney and its countercurrent exchange, serpentiginous nephrons, giving back to the body what it needs to retain and taking from the body what it needs to expel. The spleen, the pancreas, the stomach, the liver, the eye. All of it, in the past few months has been diagrammed and parceled, explained and organized. Demystified.

And now, though I can map the regions of the brain, draw its ventricles, trace the path of cerebrospinal fluid, even fathom synapse and neurotransmitter and nerve impulse, I cannot help but feel as if, when it comes to the recesses of the mind, I know a laughably small amount. My grandfather’s mind is letting go. And that is the saddest trick of it.

What anatomy can explain to me the flight of dementia? What nomenclature can be given to the mean truth of a dying man couched in disorientation and fear? When I look at eighteen brains held in the hands of my classmates, I cannot differentiate one from another—not even in the way that one heart varied from another, or muscles did, or bones. Where, then, in the crenellations of the brain’s tissue is the explanation for how a man’s reason can depart when half of his leg does? Where is the space in which his firm knowledge of his wife’s pure devotion gets lost? Where are the origins of the nightmarish visions that came to my grandfather in the interspace between life and death?

This—this seeking, based in both resolve and uncertainty, is unlikely to have any effect whatsoever on my interloping emotions from the outside world or my ability to cope with them. And yet this seeking is what I bring with me to the anatomy lab when we open Eve’s skull and remove her brain.

On the day when we are to open the skull, Trip ties a string around Eve’s head in order to draw a markered line around its circumference to guide the bone saw. We talk about the awful smell as the saw shaves a line of skull to dust and how the odor of bone is far more overpowering than it was in either the rib or the pelvic dissections. Tiny particles of bone float all around us, and we have the odd knowledge that we are inhaling specks of bone from Eve, indeed from all of the cadavers in the room, from whose heads rise wisps of smoky dust that dissipate until they vanish.

Moments like these, which are sometimes too much to dwell on, are perfect opportunities for philosophy, scientific theory, even poetry. If the whole of the universe was created from infinitely compressed matter in the big bang and if, as scientific law holds, matter is made only from existing matter and no truly new matter is ever created, then there should be no discomfort whatsoever with the knowledge that motes of another human’s body are entering my own. If I can, happily and without hesitation, accept that the molecules that now reside in my own ring finger, hip, and spleen may have traveled first from a star and then billions of times over between sea and rain cloud and frog gut and branch and soil and lambswool and ocean floor and glacial shale or any such imaginable combination, then I shouldn’t shudder to think that this palpable liberation from dead body to living one occurs at this moment, just as at any other. Three years, almost to the day, from the initial skull dissections, I will stand at the border of Higgins Lake, hoping to be pregnant, breathing in the damp November air. Though by this point I know more than enough embryology to know that even if some hope of life grows in me, it is only a few cells and nothing more, I breathe deeply. I tell the hope to take the oxygen I give it now and hold tightly to it—that the place it comes from is holy and so is the perfect sustenance for these few cells that will become the foundation of all others. As if we, at our small and singular moments in time, can discern the provenance of the air we breathe and hence judge it more or less heartening, more or less wonderful.

Bits of philosophy like these are what Trip and I talk about as long as we can, in an attempt to will away the smell of the bone dust. When we are done sawing and must take a hammer and a chisel to the line we have made to begin to remove the crown of the skull, Trip comes undone. What I did not know until that moment was that a few years before she and I began medical school, Tripler’s best friend left her apartment one morning to get coffee and a newspaper and was struck by a car. She was thrown and hit her head on the curb, which caused intense cranial swelling and left her brain dead. Trip saw her friend a last time in the hospital, with her head greatly swollen.

It is an agonizing conversation to have, particularly under such exceptional circumstances. We take an early lunch, which we eat indoors due to the inclement fall weather, but, desperate for perspective and fresh air, we bundle up and take a walk down to the corner coffee shop, where they make terrific chocolate chip cookies. We buy one to share and walk aimlessly, just to be outside and walking. We half laugh about how pretty the quad is and how we never notice, since we are only ever in the contemporary brick science building on the periphery of the undergraduate campus. One of the buildings we walk by has a row of large tinted windows at street level. In it I see our reflection—our ratty sneakers we have resurrected from dark closet corners so as not to ruin any worthwhile shoes in the anatomy lab, our thin hospital scrub pants beneath our winter coats and folded arms. I point it out to Tripler to show her how ridiculous we look, and for a moment, when we both face the mirrored glass, all I see is two young women who look deeply, deeply tired.

When we return to the lab, we have more chiseling to do, with the crown of Eve’s skull still incompletely removed. The only word we can think of to describe our actions is “barbaric.” Dale comes over while I am striking the chisel and says, “Ah, bone is her medium!” Neither Trip nor I laugh. Usually his jokes are funny and welcome, but today they strike us as irreverent and flip. We have run the gamut of emotion already today and have arrived at irritability. Our unease is compounded by our solitude. Tamara is home sick. Raj, after inexplicably missing his fourth lab the day before, leaves just prior to the skull sawing, and we are unforgiving. It is a task that has demanded physical and emotional divvying-up.

In fact, what we do not know then is that Raj will fail two of our three courses and will not even take our final exams. In hushed tones his friends will allude to the fact that he is suffering from depression. Distracted as I have been by his bravado during dissections, I will be stunned at the semester’s end when I learn that he is one of a small handful of our classmates to drop out of medical school.

When we finally have chiseled through all the remaining bony connections between the crown and the base of the skull, we twist the chisel within the crack in various positions, in order to broaden the opening and try to remove the bowl-shaped top of the skull. We do this carefully, not wanting the chisel to slip and punch through the slitted opening into the brain. With each turn of the wrist, a kind of groan issues forth from the separating bone. The slit broadens, but the skull still holds fast, so we start to use the chisels to pry the top from the bottom. We use more force than it feels like we should need to, and Trip and I both grimace quietly. Finally, with a crunch, the top is freed, and now, in order to see the brain, we must only cut through the dura mater, the outermost protective layer of the brain, which attaches to the inner lamina of the skull.

The translucent dura mater feels a little like a thin layer of nylon, flexible yet resilient. It cloaks the brain and extends through the foramen magnum at the base of the skull to become the tubular sheath that encircles and protects the spinal cord. It also dives between the brain’s hemispheres, creating a fold known as the falx cerebri. Before we can remove the brain, the falx must be cut away from the skull, and hence the dramatic midline division it provides cannot be appreciated. In order to show us the fibrous partition, Dale will show us a prosection that comes to be known as Falx Man.

Just after we remove the domed skullcap, we are called into the prosection room. Typically, the prosections are laid out on the same stainless-steel dissecting tables on which our cadavers lie. Sometimes they are entire bodies with several areas expertly dissected. Other prosections are isolated parts: an arm and shoulder, a single leg, a limbless torso. When we enter the room on this day, no such specimen is visible. We collect in a circle in the middle of the room and wait for Dale. A moment later he enters, empty-handed.

“Hey, guys,” he says warmly. “How go the heads?” Mostly we shrug in response. Trip is more candid.

“Ugh. It’s dreadful, Dale!”

Dale smiles. “This is definitely the rough stage,” he replies, “but it’s about to get really cool.” With that he is ready to go. “Okay, so this is the falx prosection,” he begins, and reaches down toward his feet, where there is a lidded white plastic bucket.

“Oh, noooooo,” Trip groans. Her overt reaction is the one all of us are having internally. We know that the combination of head dissection and a prosection that fits in a bucket is an ominous sign. As feared, Dale quickly snaps on latex gloves, reaches into the formalin contained in the bucket, and lifts out a man’s head.

In order to show the midline falx, the two upper sides of the skull have been sawed off and the hemispheres of brain removed. A two-inch strip of bone is left behind, running from between the eyes to the back of the neck. The man’s face is totally intact. Dale holds the bony strip with one hand, making the odd impression of a handled basket. With the other hand, he points to the falx, which runs down from the handle and then, forming the portion of dura known as the tentorium cerebelli, spreads perpendicularly to either side, where the base of the brain’s hemispheres would have been.

Various other structures are visible from this view, and Dale is pointing them all out to us when a classmate of mine leaves the room to be sick. It is the first time this kind of reaction has been publicly visible, and when she returns to lab the next day, she is embarrassed and explains that she had been fasting for Ramadan, and otherwise she is sure such a thing would never have occurred.

“I’ll be fine. I’m tough.”

“So yeh are, then, luv. So yeh are.”

Those who have seen the brain in surgery say that the consistency of the live brain is somewhere between mucus and Jell-O. That it is gray. When we go to remove Eve’s brain, it is firm and cream-colored. To detach the brain from the body requires us to cut its many connections, beginning with the spinal cord at the very base of the skull and including many critical arteries and nerves. Severing such important structures feels counterintuitive, and we consult the Dissector over and over to be sure that we have understood it correctly.

Reassured by the instructions, I slip my hands beneath the brain and try to lift it while Tripler gingerly aims the scalpel toward the connections we need to cut. The space in the skull is cramped and dark, and we proceed slowly to be sure that Trip does not cut something important, including my fingers. In order to give her enough room and as much visibility as possible, I am pulling the brain toward me. With each nerve and vessel cut, the brain inches steadily away from the bony base of skull, yet even once all the necessary attachments are severed, it does not emerge easily from its carapace. The Dissector instructs us to “cut…each of the remaining pairs of cranial nerves before gently ‘delivering’ the brain from the cranial cavity.” Having as yet neither reached our months of hospital obstetrics nor birthed children of our own, Tripler and I are surprised by the degree of tugging required for the “delivery.” Eventually, and not without some disconcerting tearing sounds, the brain is freed intact, and we hold it in our hands.

The experience is surreal. The brain, with its ridges and valleys called sulci and gyri looks like a contradiction: half prehistoric, half incredibly complex. Veins and arteries trace over its surface, contained in the space between the pia mater—“tender mother,” the thin, transparent membrane closest to the surface of the brain, barely perceptible, clinging to the brain tissue as it does through all of its dips and curves—and the arachnoid, whose extensions up through the dura gave this meningeal membrane its spidery name.

Removing the brain has exposed the stumps of the numerous vessels and nerves that Tripler cut, poking up through their particular bony pathways in the base of the skull. In addition to learning the identity and function of each, we have discovered a new geography of the skull that has surfaced, with foramina and fossae and protuberances galore. Too fatigued to acknowledge that new realm, we allow ourselves to be satisfied with our freed brain and call it an early day.

When I get home, I take a scalding shower. I scrub my hair, brush my teeth twice, inhale water in my nose until I choke to try to rid it of the smell of the bone dust. That night, at home, Trip calls me to check in. She says that after lab she sat in her car and cried. When I hang up the phone with her, I open the window, despite the cold, misty night, and take deep breaths through my nose. I cannot get rid of the smell. I feel ashamed at being disgusted at this moment by the bodies, their skull dust, their skinless eyes. I feel ashamed, because I understand the unthinkable gift I have been given and how it deserves to be met with steady appreciation and reverence. I am ashamed to feel disgusted. But I am.

My journal from the time reflects the tension of the head dissections, yet also hints at their rewards:

Anatomy takes a nasty turn once we go above the neck. Not only does the information increase in detail like crazy (the skull is amazing in its intricacy—seemingly endless numbers of holes, indentations, seams, processes, all of which have beautiful Latin names and some kind of function for development, protection, collection), but the intensity of the dissections seems to multiply exponentially. Everything that I perceived to be difficult before pales, and by “difficult” I mean a host of things. Emotionally, the dissections are certainly far harder. We are peeling off the skin of the face, we are removing the scalp, we are tugging out the eyeball. But physically they are harder, too. We must saw around the circumference of the skull, chisel through the orbit, the jaw.

We chisel through the atlas, the perfectly named vertebra that holds the skull, and then pull the head up and forward so it flops down on the body’s chest, now connected to the body only by the muscles that attach the sternum to the jaw, leaving a stump of neck one would imagine from a guillotine or an executioner’s blade. Eventually we saw the head in half lengthwise, which is a gruesome and tiring task. I have some visceral reactions during these times, and so do my classmates.

The force necessary in the dissections feels barbarous, and I am still fascinated by what is revealed but hate the push and tug necessary for revelation. It feels wrong to push against the back of the head so strongly that you know the nose is smashed against the table; knowledge of pain’s absence does nothing to remove the feeling that what you are doing is something that should not be done to a person, especially someone who has entrusted her body to you.

My dreams at night are full of Eve. I am Persephone, somewhere between the living and the dead. Feeling increasingly uneasy.

It is December, and the end of the term approaches. Mornings, a tight grip of frost clings to my windshield. It is still dark as I drive into campus, and my breath forms white clouds the moment it leaves my mouth—the way in which my body has changed the air made manifest. The snow on the ground looks blue in the darkness, except for the occasional yellow halos cast by the streetlights that send the shadow of my car, distorted and large, behind me as I drive. Even as the hours of darkness are lengthening, my nights of sleep have grown shorter and shorter. Exams are looming, and when I do turn out the last light in the house and, drained, climb into bed, even my dreams are overtaken by medicine. Odd mixtures of all of my coursework combine in fruitless nighttime anxiety, and when I wake, I am grouchy and unrestored—not even sleep is a respite from tension, from the feeling that some untended thing needs to be understood, or committed to memory.

The cranial bisection—the sawing of the skull into two symmetrical halves—splits Eve’s head between the eyes, divides the nose and lips and tongue and chin in two. When we reach the mouth and see perfectly pink gums, we realize for the first time that Eve still wore her dentures. Wordlessly, Trip pries them out with her fingers, sets them on the table beside Eve’s right shoulder, and we continue the cleaving.

When the bisection of the head is complete, the few remaining days of the semester are spent in review for the final exam. My classmates and I have finished dissecting our cadavers. However, the need to prepare for the upcoming exam and our fatigue from partitioning and studying the head combine to make this accomplishment anticlimactic. There is no celebration or commemoration. We merely segue into reviewing the structures we have forgotten and committing to memory those we have recently exposed.

Initially I find my discomfort with the head dissections discouraging. After all, hadn’t I been feeling increasingly at ease in the anatomy lab over the course of the semester? Now, as the course draws to a close, shouldn’t I notice a real difference from those first, tentative days? I fear that my regression into fitful sleep and edginess somehow marks my failure as a doctor-in-training. Yet, increasingly, I am now able to hear the symptoms of a patient and have some sense of what might be wrong. I can pick up Eve’s arm, or heart, and name its innermost structures; I can trace the flow of blood through her body, naming her arteries and veins. What does it mean that my emotional progress is more difficult to chart?

I think the reality of doctoring may be that in medical school, and in the years of training and practice that follow, clinical comfort steadily increases. Concepts that were initially elusive become clear; procedures that seemed impossible are eventually done with ease. Most importantly, a gestalt view of the body begins to build, so that injury and disease become easier to identify and the corresponding means of returning the body to health are more comprehensively understood. Nonetheless, comfort with certain wrenching tasks—the most difficult dissections, assessing a severely injured trauma patient, delivering a terminal diagnosis to a young person—must naturally wax and wane. I think that Deborah was right when she suggested that the emotional challenge of anatomy class might be partially intended to prepare my classmates and me for the rigors of tending to patients whose bodies are sick and maimed. Yet I also believe that the lesson of anatomy is that we do not need to overcome all our emotion or conquer all difficulty in order to be good clinicians. In fact, in light of the important balance that clinical detachment requires, I should perhaps feel encouraged by my inability to always emotionally disengage.

Eve’s body has been thoroughly dissected, and we still do not know why she had no belly button. Dr. Goslow hypothesizes that she had some kind of abdominal surgery and that in the closing of the surgical wound the umbilicus got tucked in, like a seam. “But there’s no scar,” we protest.

He shrugs. “Maybe she had the surgery at such a young age that the scar just faded away.”

We are not satisfied. There was no evidence of major surgery inside Eve’s abdomen. There was no scar. And so it remains a mystery, a symbol of how some things about Eve remain unknowable, that our understanding of her cannot help but be only partial, even after the dissection is complete.

The semester ends in a blur of studying and exams, of sleep deprivation and note cards. When the final exam is behind us and I have officially finished my first semester of medical school, I find myself returning at unexpected moments to thoughts of Eve. And the thoughts are less and less the intrusive, troubling ones that interrupt my sleep and disrupt my mood, and more a deepening sense of gratitude and awe for Eve. Poor, dead Eve, who came to me beautiful and whom I have reduced to a shambles of muscle and bone, cut away and divided. Eve, who has, among other things, given me a sure and indisputable understanding of the impenetrable fact of death. I do not shudder at all to think of my body, or the bodies of my loved ones, burning to dust. Eve has shown me that no matter how gravely a dead body is altered, its lifelessness is the one aspect that does not budge.

I think of Eve’s family in their mourning, some years ago, and cannot imagine that the thought of her body in the anatomy lab was to them either comforting or sacred. I wonder if her ability to donate her body came from the very knowledge that she gave to me: No harm can come to one after death. I wonder if she shared that knowledge with her family, and if it brought them peace.

I think of the vast amount of knowledge I’ve acquired since the year began. When my mother called me to tell me about the surgery on my grandfather’s leg and said “femoral artery bypass,” the vessel I pictured was not my grandfather’s but Eve’s. I have never seen the right middle cerebral artery that occluded to leave my grandmother’s left side debilitated, but I have seen Eve’s and can picture its precise path and the brain matter it nourished.

Truly, when I listen to any patient’s heartbeat or lungs, or feel for someone’s liver or pulse, or find tendons to tap with my hammer in order to test reflexes, the structures I picture hidden beneath the skin are all—all of them—Eve’s. As Vesalius and William Harvey and Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci knew, the body’s interior is a black box into which we grope and guess, unless we have had a chance to unveil it and see beyond the mystery. I cannot begin to know what led Eve to give me such a gift, whether it was practicality or altruism or cynicism or love of science or some other, equally unknowable, aspect of her personality or life. What I do know is that she neither knew me nor knew anything about me, and yet she bequeathed to me this offering, unthinkable for centuries, that has formed the foundations of my ability to heal. My hours with her neither cured her nor eased her suffering. Bit by bit, I cut apart and dismantled her, a beautiful old woman who came to me whole. The lessons her body taught me are of critical importance to my knowledge of medicine, but her selfless gesture of donation will be my lasting example of how much it is possible to give to a total stranger in the hopes of healing. That lesson, when I am called to treat critically ill patients who no longer appear human, and prisoners, and demented grandfathers who are dying and angry and scared, is the lesson I hope beyond all else to have absorbed.