CHAPTER SEVEN

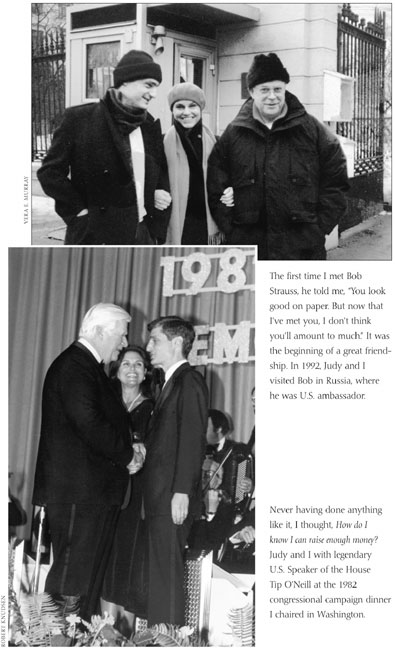

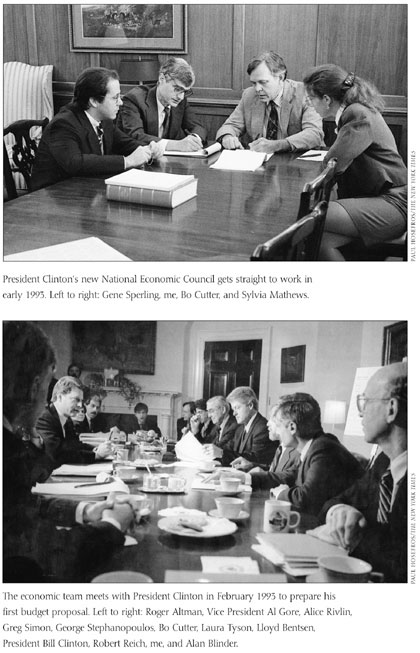

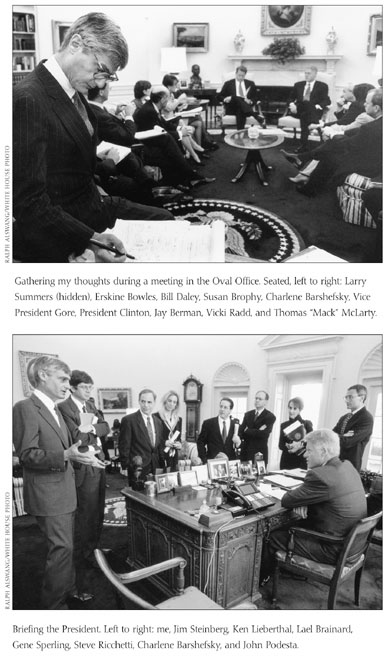

Talking Softly

I CONTINUED TO BE STRUCK by how different being at Treasury was from life in the White House. In many ways, heading a cabinet agency is like running a business, but someone who goes from the private sector to a cabinet position can easily be misled by the similarities and consequently fail to learn to deal with the differences. As a cabinet officer, you’re the head of a large, hierarchically structured organization. As Bob Reich told me when I moved to Treasury, you get to “run your own show,” much as a private-sector CEO does. In both worlds, setting objectives, establishing effective accountability, and having capable people are crucially important.

But the two worlds are different enough that the analogy to corporate structure can prevent a former CEO from being effective in government. In a noticeable sense, you don’t run your own show; the White House does. Goals, as I had already discovered, differ in government and the private sector. In business, the chief focus is on profitability. Government, by contrast, has no simple bottom line but rather a vast array of interests and priorities, many of which exist in a state of tension or conflict. For that reason, decision making in government is vastly more complex.

At Treasury, I also found a difference from business in terms of authority. Many former business executives feel great frustration when they discover the limits on their ability to act in government. I had not been accustomed to, nor did I expect, a corporate-style hierarchical structure. But even I was surprised at what limited power I had in my own building. The various bureaus and agencies that are part of the Treasury Department operate with considerable independence. Just because you are dissatisfied doesn’t mean you can make changes. Even with respect to the Treasury Department proper, many familiar management tools were not available. A private-sector CEO has the power to hire and fire based on performance, to pay top managers large bonuses, and to promote capable people aggressively. At Treasury, I had the power to hire and fire fewer than 100 political appointees among the 160,000 people who worked under me. Others could be dismissed for gross incompetence, but the practical obstacles to doing so made it seldom worth the effort. In general, the quality and commitment of many career civil servants was a great positive surprise during my time in government—but the rules were rigid and needed bold overhaul.

Furthermore, most structural departmental reorganization couldn’t be done on my own, but required legislation. Even closing an inefficient IRS field office would mean a time-consuming and often unsuccessful discussion with that state’s congressional delegation to avoid creating damaging political ill will. Luckily, as Roger Altman told me before I arrived, the organizational structure of the Treasury Department, which had been in place for many years, was basically sound.

The biggest difference in both process and authority is the organizational complexity involved in making major Executive Branch policy decisions. In the private sector, a CEO has more or less free rein. In a presidential administration, everything revolves around the White House and almost every major policy decision is brought into the White House, often through an extensive interagency process. Moreover, most significant decisions made at the cabinet level are reexamined at the White House not only for substance but for their “message” and political dimensions. As a cabinet secretary, you wear two hats at the same time—one as head of your agency, the other as part of an administration in which everything revolves around the President. And to be successful in the cabinet, you have to be skillful at working within the White House process on issues that affect you. The White House staff may have great and even decisive influence on policy decisions you think you should be making. Sometimes the cabinet agencies and White House work in harmony, sometimes they operate in ignorance of what the others are doing, and sometimes they go to war with one another.

Presidents have dealt with this problem in various ways. The National Security Council was created in 1947 to coordinate the different bodies involved in foreign policy. To deal with domestic and economic issues, Presidents have tried various approaches. Richard Nixon proposed having four cabinet supersecretaries, organized around subject areas, but never got to implement the idea. Some Presidents have tried to coordinate through lead cabinet members, but often not successfully. And President Clinton, as I discussed earlier, created the National Economic Council.

Clinton’s Health and Human Services Secretary, Donna Shalala, had it right when she told me that the position of a cabinet secretary is, in a sense, schizophrenic. You’re the boss in your own building—albeit with less authority than you’d have in the private sector. But when you come to the White House and sit around the table, you may have less influence than a thirty-some-year-old staff person, despite your august title and the trappings that go with being a cabinet member. For some, it’s hard to keep these two roles straight, and the complexities can create considerable stress and tension. Longtime officials at the Treasury Department sometimes recalled one of my predecessors, who was notorious for threatening to resign every few days after blowups with the White House.

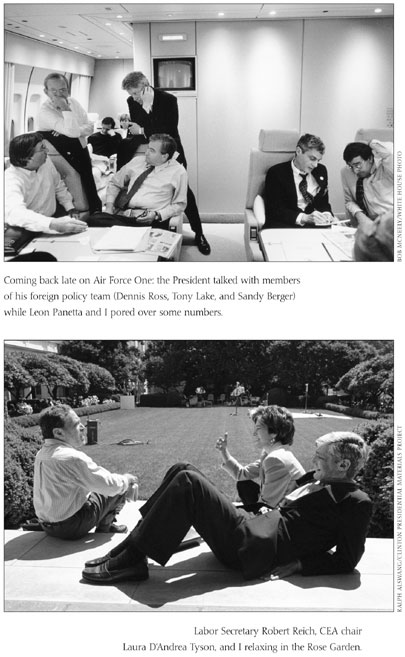

When I moved to Treasury, I had the advantage of having already developed a sense of the relationship between the cabinet agencies and the White House from the other side of the fence. Working at the NEC for two years, I had gotten to know the thirty-year-old staff people, respected their experience in policy and politics, and thought of them as colleagues. I also understood how the Clinton administration really functioned, including the importance of the daily early-morning staff meeting in the Roosevelt Room and the smaller meeting-after-the-meeting in the chief of staff’s office. That’s where the administration’s agenda was set and all sorts of decisions about the interplay of policy and politics, including congressional strategy and media strategy, were made. I never relished showing up for work at 7:30 in the morning. But after my move to Treasury, I told Leon Panetta that I’d like to keep coming to the daily staff meetings because Treasury was involved in so many issues. Leon said okay, although no other cabinet members attended, other than those located in the White House complex.

Many of Clinton’s cabinet secretaries were fully effective without being part of the daily White House process. But for me, attending those meetings addressed the “schizophrenia” problem and kept me in the thick of everything going on in the Clinton administration. Erskine Bowles, who succeeded Leon as chief of staff in 1996, agreed that I could keep coming. Having run the Small Business Administration during Clinton’s first term, Erskine understood the problem of isolation inside the departments very well. He once said to me, “If you’re running an agency, you feel like you’re on the moon.” Erskine has accomplished many things in his career, none of them more important, in my view, than moving the morning meeting to 7:45.

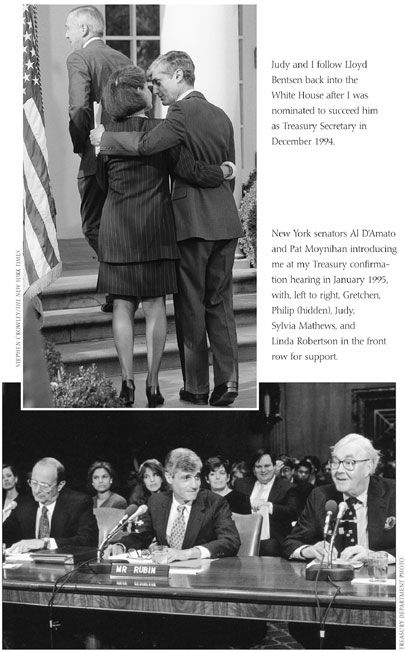

Becoming Treasury Secretary also enormously increased my activity on Capitol Hill. At the NEC, I had had some involvement with Congress, but only at Treasury did it become a part of my daily life. The first of those interactions was my confirmation hearing. Linda Robertson, then Treasury’s deputy assistant secretary for public affairs, was the quarterback of this effort. She and her colleagues used this preparatory process to bring me up to speed on all of the many aspects of Treasury, to introduce me to the key people, and to discuss questions that might arise. At the hearing itself, before the Senate Finance Committee, both New York senators, Alfonse D’Amato and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, joined me at the table to make the formal introductions, and then I was on my own. On the one hand, I didn’t anticipate any great difficulties; on the other hand, it was always possible that some senators might use the hearing—and me—as a vehicle for attacking the administration. And, since White House staff does not testify before Congress unless required to in some investigation, this was my first hearing as a public official and it was being nationally televised on C-SPAN. I felt some natural unease, but I remember feeling buttressed by thinking of my younger son, Philip, who was sitting right behind me, and his sense of perspective and wry, ironic view of life.

Committees that oversaw Treasury’s budget could direct departmental management and might, in some instances, try to affect policy positions as well. And, of course, virtually all major policy decisions were subject to congressional approval, or at the least to congressional inquiry and hearings. And beyond the question of oversight, members of Congress tried to exercise influence over how we ran the agency and the scope of my job. I remember Trent Lott (R-MS), who was then the Senate majority whip, asking me to come to his Senate office that first year. When I got there, he told me that, as Treasury Secretary, I shouldn’t be delving into social programs and the like. My job was worrying about the dollar and interest rates. I didn’t know quite what to say, so I disagreed respectfully.

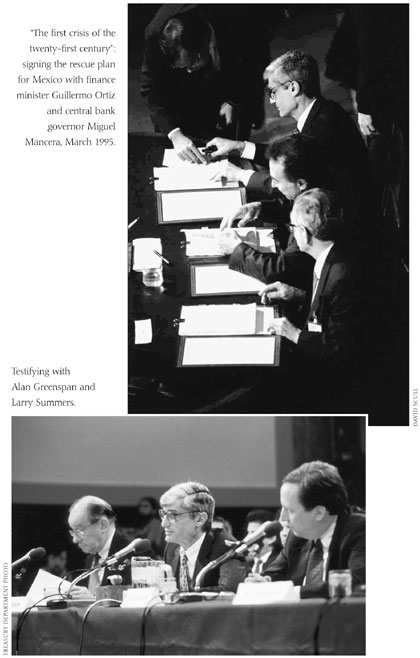

For all these reasons, one’s relations with key members and congressional committees are key to being effective and require a great deal of time and thought. In testifying before Congress, my approach was to apply what I’d learned about client relationships at Goldman Sachs: be well prepared, responsive to their concerns, and highly respectful. The master at the art was Alan Greenspan. Alan would doff his cap in the direction of a question, even if, on occasion, it was somewhat off the mark. “That’s an interesting observation you make, Senator, about the earth being flat,” he’d say. “If I might, let me rephrase the question.” Alan would then ask himself a completely different question and answer it with such complexity and finely calibrated nuance that the questioner faced a choice between nodding intelligently and acknowledging his own confusion. I must say that testifying next to the chairman, I was sometimes completely baffled myself.

Alan would then ask the House member or senator, “Does that respond to your question?”

And the interrogator would invariably say, “Yes, it does.”

In many other instances, of course, congressional testimony meant a real dialogue—and sometimes disagreement—on serious issues, but even those exchanges were best conducted with a highly respectful tone toward the interlocutor.

Press relations also took on a different dimension after I became Secretary. Before moving across the street from the White House, I never thought about how much of a role the media plays in the daily life of the Secretary of the Treasury. As head of the NEC, I could speak for the administration, but I wasn’t the point person. As Treasury Secretary, even though many others comment on economic matters, I was the administration’s principal spokesperson on the economy. I was expected to represent the President’s budgets, his tax proposals, and his views about any sort of economic crisis, problem, or event. I also represented the U.S. government at international summit meetings, such as the regular gatherings of finance ministers from various groupings of countries—the G-7, G-10, G-20, and so on. Because of this formal role, anything I said that had implications for financial markets could cause them to respond swiftly and powerfully. The markets might also react to comments by the NEC chairman or various other administration officials, but ordinarily not nearly to the same degree.

To avoid moving markets, I had to be consistent and highly disciplined in not only what I said but precisely how I said it. The most sensitive area was exchange rate policy. Because of Treasury’s ability to buy and sell currencies for the purpose of affecting exchange rates, the markets would respond to almost anything I said that seemed to make intervention more or less likely. Affecting exchange rates unintentionally would make me look undisciplined and unsophisticated. My credibility, with respect to our currency, could be especially critical if at some subsequent time we had a weak dollar and faced the possibility of a dollar crisis.

My substantive view was that economic fundamentals determine exchange rate levels over time, and that we should focus our attention on strengthening U.S. economic policy and performance, not on influencing the level of the currency. I also believed that a strong U.S. dollar was very much in the national interest. This was different from the question of whether our exchange rate was overvalued, though people often had difficulty recognizing that distinction. My rhetorical position thus always adhered unvaryingly to that policy, both because that was substantially right and to maintain confidence in the currency.

A strong currency means that American consumers and businesses can buy imported goods and services more cheaply and that inflation and interest rates will tend to be lower. It also puts pressure on American industry to increase productivity and competitiveness. These benefits can feed on themselves as foreign capital flows in more readily because of greater confidence in our currency. A weak dollar would have the contrary effects. A strong dollar does make imports cheaper—and therefore more attractive—in the United States, and American exports more expensive overseas, tending to increase the current account deficit. However, that is a problem with many underlying causes, including the gap between savings and investment in the United States.

In my view, the sensible way to deal with the risks that can come with a large and sustained trade gap is not to promote a weak dollar as an instrument of trade policy, which, in addition to its other drawbacks, could set off competitive devaluations. Instead, we should act to increase savings in the United States, especially by improving the government’s fiscal position, and to increase productivity to make American goods more competitive. At times, though, the dollar may trade for an extended period at a high degree of overvaluation relative to the fundamentals. An overvalued exchange rate that makes goods and services less competitive in world markets than warranted by comparative efficiency results in undesirable dislocations and will likely not be sustainable. Whether to try to correct this, and how to frame such action, is a very difficult judgment.

Some saw a tension between my basic stance in favor of a strong dollar and our action on rare occasions to spur a market correction of what seemed an undue rise in the dollar against a particular currency. But when we took this action, we were operating within the context of our strong-dollar policy. I was skeptical about the efficacy of currency “interventions” per se—that is, of governments trying to influence the exchange rate of a currency by buying and selling large quantities in the open market. My experience with foreign exchange markets at Goldman Sachs led me to believe that trading flows were simply too vast for such interventions to have more than a momentary effect, except in very unusual circumstances. Basically, currency levels reflect the market’s expectations—and the realities—of a country’s fundamental economic situation relative to the economic fundamentals of other countries: fiscal conditions, interest rates, inflation, and growth.

In any case, whatever my views were about whether the dollar at any given moment was too strong or too weak relative to economic fundamentals, I virtually always said exactly the same thing: “A strong dollar is in our national interest.” A lot more thought went into that small phrase than was evident from my boring repetition. The repetition reflected not only my belief in a strong dollar, but also my belief in leaving markets to market forces. The slightest shading, such as going from “I believe a strong dollar is in our national interest” to “I believe it’s in our national interest to maintain a strong dollar” could have market effects, even if no change in view was meant.

At press conferences at home or on the road, reporters from financial publications would try to engage me in a cat-and-mouse game. They would ask the same questions about the dollar and the stock market again and again, each time with some new twist, hoping to elicit something different from my standard response—a response that was always true on its own terms but not necessarily a complete answer relative to the circumstances at any given time. I had said a strong dollar was in our national interest when one dollar could buy 120 yen. Now the yen was at 130—was the stronger dollar better? How strong was too strong? Wire service reporters kept their cell phones on to broadcast my remarks directly to their news desks, in case I disgorged some unexpected nuance. But I became very adept at simply repeating my mantra—except in those rare instances when we deliberately used a slight shading, always built around commitment to a strong dollar, to convey a message. For example, my saying “A strong dollar is in our national interest, and we have had a strong dollar for some time now” created great excitement at a press briefing, as it was construed to mean that we wouldn’t mind seeing the dollar remain strong but soften somewhat. However, I would never give any explanation for such a change beyond my prepared phraseology.

A good illustration of how sensitive markets can be is what happened when I was testifying before the Senate Finance Committee in June 1998. At that point, the Japanese yen had fallen to 141 to the dollar, its lowest level in eight years. The weak yen seemed to have reached a troubling extreme and was exacerbating our trade deficit by making Japanese imports cheaper in the United States and American exports more expensive relative to Japanese products in overseas markets. Of even more urgent concern at that moment was that the falling yen could worsen the economic crisis that had then been afflicting Asia for nearly a year, by putting pressure on the currencies of the troubled Asian countries and by motivating China to devalue its currency. When Senator Frank Murkowski asked me about the possibility of U.S. intervention to support the yen, I said that intervention was “a temporary tool, not a fundamental solution.” Weakness in Japan’s currency, I said, reflected the underlying weakness in Japan’s economy. In order to raise the value of the yen, the Japanese would have to address their fundamental economic problems.

That was all correct, but in focusing on Japan, I mistakenly discussed intervention in an intellectually serious way. Larry, who was sitting next to me, passed me a note that read, “Bob—Yen has moved to 143.20 in last 15 minutes. I think we need a little more saber rattling.” In other words, the foreign exchange markets were interpreting my remarks to suggest I had made the possibility of intervention to support the yen less likely, and were selling yen against the dollar. In fact, my policy views had not changed at all: I was never enthusiastic about currency interventions, but I didn’t rule them out as an occasional tool.

After reading Larry’s note, I hastened back to my normal level of opacity, offering the clarification that I didn’t want anyone to infer that I was suggesting that intervention was not an appropriate tool to affect the short-term direction of currencies. “We have often said in the past, Mr. Chairman, that we will intervene when appropriate and not intervene when it’s not appropriate, but it is always a tool that is available for the kinds of impacts that it could have.”

This was not especially useful guidance, a point Senator Moynihan picked up on immediately. “And you will always know when it is appropriate and when it is inappropriate?!” he interjected.

But my clarification was unavailing. The yen continued to fall that day, to 144.75 to the dollar. We hadn’t adjusted our policy on the yen-dollar relationship or on currency intervention in the slightest. But currency traders were reading nonexistent meaning into my comments, even after I said that I hadn’t meant what they’d thought I’d meant. An episode like that demonstrated the value of discipline and, on exchange rates, of avoiding interesting discussions and sticking to carefully wrought stock phrases.

Having said all that, currency intervention can make sense on rare occasions. Just a few days later, with the yen continuing to fall against the dollar, I felt the conditions that can make a currency intervention effective might well be present. The first was that the yen-dollar exchange rate, now at 147 yen to the dollar, seemed to have gone to a real extreme—the yen was approaching free fall. American manufacturers, who were always worried about the level of the dollar, were becoming truly alarmed. The second condition was that the intervention would be supported by policy changes. Japanese officials were prepared to make a series of statements supporting economic reforms we were encouraging, such as closing insolvent banks. (Whether they would follow through with such promises was another question, but their going on the record seemed like progress.) The final condition was the psychological element of surprise. If the markets expected you to act, that would already be reflected in market positions and prices and tend to vitiate the impact of the action. My well-known bias against currency intervention—and even my unintentionally direct Senate hearing remarks—were helpful here. For this kind of move to be successful, surprising the market can be key.

But despite propitious conditions, I still felt that the odds of success might not be good enough to warrant intervention. Alan, Larry, several top Treasury officials, and I debated the pros and cons at length. Japan’s economic slide urgently required economic reform that the government seemed unable to accomplish. How much reform commitment had to accompany the intervention for the market to react? And I was concerned, as usual, about the effect that an unsuccessful intervention might have on our credibility. But Larry and Tim Geithner made a strong case that intervening in support of the yen was a risk worth taking, largely because of what was happening elsewhere in Asia. After many, many hours of discussion, they persuaded me.

That decision illustrates another point about decision making. While keeping your choices open for as long as possible—a proclivity of mine that Larry termed “preserving optionality”—is desirable, the markets don’t wait for you. As we continued our discussion into the early evening, in the Far East the new day was under way and we had to decide before the Tokyo markets opened. When the markets opened the next morning in New York, we would be too late. So rather than continuing our deliberations in the hope of new information or new insights, I had to make a decision without further delay.

In this case, the intervention worked—which is to say that the psychology of the foreign exchange markets was clearly affected. When the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which acts as the Treasury’s agent in the foreign exchange markets, converted $2 billion into yen, currency traders were caught by surprise and the exchange rate moved all the way back to 136 yen to the dollar. Although the larger issues related to Japan’s economic weakness remained, the yen never again reached the lows of that summer. We intervened very seldom, and each of our interventions was successful.

ANOTHER CONSTANT FACTOR in the life of a Treasury Secretary is the stock market. As my time at Treasury went on, my personal view was that excesses were probably building. The U.S. bull market had begun in 1982. By the second half of the 1990s, investors were asking much less of a risk premium for investing in equities than they had historically. People had come to believe that stocks would bounce back reasonably quickly from any decline, as they had from the sharp drop in October 1987; that stocks always outperform bonds over the long term; and that stocks involve minimal risk if you hold on to them. The proliferating financial news on television and book titles such as Dow 36,000, published when the Dow was around 11,000, exuded financial market euphoria. The attitude of people who grew up in the 1980s and ’90s was the mirror image of people I had known who grew up during the Depression. Whereas many people of my parents’ generation never lost their wariness about investing in the stock market, many people of my generation and younger were equally conditioned toward complacency.

My view was that nothing had changed to reduce the substantial risk that has always been associated with stocks. From the last day of 1964 to the last day of 1981, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fluctuated a great deal, but the closing price was roughly unchanged—meaning it had declined substantially when adjusted for inflation. We were now in the midst of a bull market of similar duration that could potentially be followed by a long period of underperformance. In Japan, in admittedly different circumstances, the Nikkei average lost roughly three quarters of its value between 1989 and 2003.

Many new investors weren’t knowledgeable about stocks and were investing based on theories that were oversimplified and, at worst, simply incorrect. Take the popular hypothesis that stocks outperform bonds over the long run. This has been true historically, though the assumption that the future will resemble the past remains exactly that—an assumption. Moreover, stocks might have ceased to be undervalued in relation to bonds once investors became aware of the phenomenon and priced it into the market. Leaving that issue aside, what’s true of market aggregates is not necessarily true of any one portfolio, which is subject to the performance of particular companies. A preference for stocks in general doesn’t help you understand valuation or choose investments wisely. Moreover, while buying stock index funds and holding shares for a couple of decades or longer may provide a good likelihood of a distinctly higher return than bonds, history also indicates that markets can provide subpar returns for lengthy periods. Even if the stocks-versus-bonds thesis is correct, not all investors have a time horizon of sufficient duration to benefit from what might be a very long run—for example, if you’re planning to retire on your savings in five or ten years or don’t have the psychological staying power to withstand a long drought. All of this was relevant—but ignored—in the subsequent political debates, at the height of the bull market, about reforming Social Security by creating individual equity accounts.

As it seemed more and more likely that stock prices were excessive—and that the NASDAQ was almost manic—I became increasingly concerned that a sudden return to historical valuation levels could do harm to the economy. My considered view was never to say anything about the level of the stock markets, but with possible serious overvaluation posing larger risks to the economy, was there anything I could do about it? Alan, Larry, and I talked about this issue as the Dow broke 5,000, 6,000, 7,000, 8,000, and 9,000. Warning off the investing public might have seemed tempting, but I thought, and still think, that public officials ought not to comment on the level of the stock market—and that applies when stocks seem undervalued relative to historical trends, just as when they appear overvalued. A Treasury Secretary serving as a market commentator and hoisting a green, red, or yellow flag depending on his current view is a genuinely bad idea for four reasons. First, whatever our opinions might be, nobody can say what the “correct” level of the stock market is—or whether the market is overvalued. My personal alarm bells started ringing thousands of Dow points below the peak, and I know very shrewd people who were bearish at many points during the great bull markets of the 1980s and ’90s. Having been wrong then, I was reminded that I could well be wrong now.

Second, I think any comments I made probably wouldn’t have had any effect. An object lesson occurred on December 5, 1996, when Alan Greenspan posed a rhetorical question in a speech: “But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions . . . ?” I’m not sure Alan was even intending to express a view about stock prices. But markets thought the “irrational exuberance” phrase was deliberate and the Dow declined the next day, from 6,437 to 6,382. Then the bull market resumed its run—for another 5,000 points. The only lasting effect of Alan’s comment was to win him a probable future entry in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations.

Third, I believed that attempts to influence financial markets through words not only would be ineffective but would harm the credibility of the individual making the effort—because knowledgeable people will understand that he has no special insight, and because he’ll almost surely be wrong a good bit of the time. By undermining the credibility of policy makers, such attempts could erode confidence and damage the economy itself. Finally, a gradual decline of an overvalued stock market can be readily absorbed. But if an official’s comments, for whatever reason, precipitated a rapid and substantial market decline, that could be economically disruptive.

On the other hand, I did, in speeches and television interviews, what seemed appropriate and useful, namely advise investors to focus adequately on risk and valuation, and express concern that these disciplines had flagged. That seemed to me a sound approach no matter what the state of the market might be and carried with it none of the disadvantages of comments on the level of the markets.

By mostly refraining from comment, Alan and I differed greatly from our Japanese counterparts, who tended to take the view that markets should be managed by policy makers. I remember one bilateral meeting with a Japanese finance minister where the issue arose of whether our stock market was too strong. The Japanese official said to me, “Why don’t you bring the stock market down?” Obviously, government actions, including fiscal and monetary policy, do affect equity markets. But the Japanese view was that government can affect markets by providing guidance or, in the case of currency rates, through intervention. My view, and that of most American economists and policy makers, is that the impersonal judgment of a vast number of participants guides markets. Over the longer term, stock markets, like currency markets, tend to reflect fundamental economic conditions, although they often diverge from those averages and go to excess in one direction or the other, sometimes for extended periods. In any case, in the long term as well as the short term, markets are going to go where markets are going to go—with jawboning by government officials unlikely to have more than the briefest effect, at most. As I often put it to others in the Clinton administration, “Markets go up, markets go down.” Some people viewed this as a profound observation. To others, it was the most obvious of truisms.

All that notwithstanding, in rare instances a Treasury Secretary probably does have to say something about unusually dramatic movements in the stock market. On October 27, 1997, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 554 points, its largest-ever single-day point drop at that time. The precipitating factor was a decline in foreign markets brought on by the Asian financial crisis, which created widespread concern in U.S. markets that the problems might spread to us. Adding to the psychology of the situation was that, just ten years and one week before, the Dow had suffered what was then the largest point drop in history, the 1987 stock market crash. People started referring to “Black Monday II.”

Now, 554 points in 1997 was a 7.2 percent decline, far less significant than the 508-point, or 22.6 percent, drop on Black Monday in 1987. Moreover, ten years earlier, the crash had overwhelmed the systems that processed and cleared buy and sell orders. As a result, the New York Stock Exchange had temporarily ceased functioning in an orderly way. This time, the market’s order-clearing and protective systems had worked much better. Trading had been halted before the end of the trading day by the so-called circuit breakers put into place after the 1987 crash. Nonetheless, the fall worried us, in the context of large declines and growing market volatility at home and abroad, and had been receiving intense media attention throughout the day.

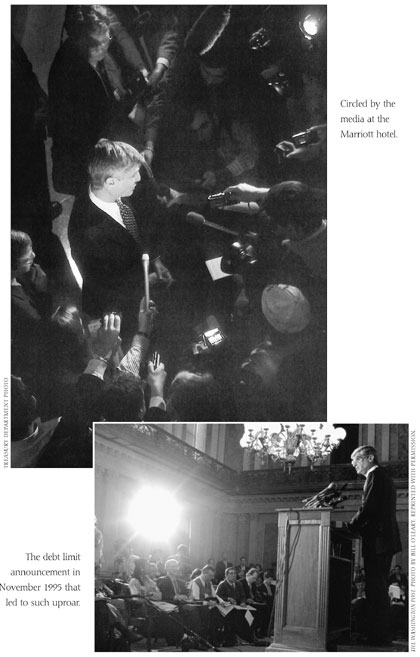

I was torn about whether to say something publicly. On the one hand, I did not want to be in the position of cheerleading the stock market, since that is intellectually dishonest, very unlikely to work, and potentially counterproductive with respect to confidence. On the other hand, the great nervousness and uncertainty in the U.S. financial markets seemed to call for a reassuring presence. Larry Summers, Alan Greenspan, Gene Sperling, and I decided, after much discussion, that I should make some statement. We didn’t want or expect to affect the market’s direction, but we did want to try to diffuse a panicky environment. Our hope was simply that whatever was going to happen would happen in a calm, orderly fashion, as opposed to what had occurred in 1987.

With Greenspan at the Treasury, the four of us spent more than an hour with other Treasury officials constructing a brief statement. It said that I had been in touch with other officials, that we’d been monitoring developments closely, and that these consultations indicated that market mechanisms, such as the systems for settling trades, were working effectively. The statement continued, “It is important to remember that the fundamentals of the U.S. economy are strong and have been for the past several years.” As a final note, we added that the prospects for continued growth with low inflation and low unemployment remained good.

The delivery of this statement was a dramatic moment. I walked down the steps of the Treasury Department and read the statement we’d worked out to a vast number of television cameras. Then I turned around and, ignoring the questions being shouted by members of the press, walked back inside. This was treated as a major news event; the networks broke into their regular programming to carry it live.

The next day, the stock market recaptured some of its losses, and the news media expressed a general view that my comments had served a useful purpose. Having somebody who is viewed as possessing some measure of credibility with respect to markets and economic matters speak in a calm and thoughtful fashion, even if he says nothing that is relevant to the immediate market phenomenon, probably does contribute positively to the psychology of a volatile situation. One advantage of avoiding frivolous market commentary is that one builds and maintains a credibility that can be drawn upon when it is really needed.

Given the remarkable rise in the Dow following Clinton’s election in 1992, political people in the White House often wanted the President to take credit for the strength of the stock market. I argued that for Presidents to validate their policies by pointing to the stock market’s performance was always a mistake. The stock market could fluctuate for all kinds of reasons and could overstate or understate reality for extended periods. I sometimes dissuaded Clinton’s advisers by using the argument that if the President took credit for the rise in the stock market, he’d get the blame for the fall as well. Live by the sword, die by the sword.

BECOMING SECRETARY of the Treasury greatly increased my interaction with the Federal Reserve. At the NEC, I had always supported the Fed’s independence with regard to monetary policy, and I continued to do exactly that at Treasury. The basic logic here is familiar: the head of a country’s central bank has the job of acting countercyclically—prompting growth during economic slowdowns and constricting the money supply when strong growth threatens to produce inflation. The latter task is intrinsically unpopular. As the longest-serving Federal Reserve chairman in history, William McChesney Martin, famously said, the Fed chairman is the fellow who takes the punch bowl away just when the party is getting going. That’s why the chairman should have a fixed term, which he does, rather than serving at the pleasure of the President. This helps insulate him from political pressure.

Before 1993, Presidents and Treasury Secretaries had sometimes opined on what the Fed should be doing with regard to interest rates and sometimes tried to lean on the Fed chairman in various ways. Bill Clinton, by contrast, always adhered to the principle of not commenting publicly on Fed policy. Whenever the contrary suggestion was made inside the White House, I argued that commenting was a bad idea for several reasons. First, and most fundamental, the Fed’s decisions on monetary policy should be as free from political considerations as possible. Second, evident respect for the Fed’s independence can bolster the President’s credibility, economic confidence, and confidence in the soundness of our financial markets. Third, the bond market might be affected by any belief that the Fed chairman was under political pressure that could affect the Fed’s actions. There was also another factor I came to recognize after moving to Treasury: we advised other countries around the world, such as Mexico during the peso crisis, that their central bank governors should be insulated from political pressure. Attempting to put political pressure on our own central bank could undermine that prescription.

Whatever a President’s philosophy about publicly commenting on the Fed, every President probably complains about it privately from time to time. There’s a natural tendency to second-guess any decision not to let the economy grow faster, especially when such a decision comes in advance of an election. Even with President Clinton, who respected the Fed’s independence both in principle and in practice, behind-the-scenes discussions sometimes grew rather heated. In 1994, a few people in the White House suspected—totally wrongly—that Alan Greenspan, a Republican, might be raising interest rates more than necessary out of some kind of political bias. I responded that Greenspan seemed to me to be trying to extend the recovery by preventing the economy from overheating. That would ultimately benefit the President politically when he ran for reelection in 1996.

Greenspan’s actions in 1994 were vindicated by subsequent economic developments. But such suspicions of political motivation, though not warranted in this case, leave nagging questions. What should be done if the Fed chairman is consistently wrong or ineffective or politically motivated, and who should make those judgments? We obviously never had to face those quandaries with Greenspan, but they have no easy answer.

At Treasury, my personal relationship with Greenspan also grew much more familiar. The Treasury and Fed staffs work closely together on a range of issues, despite what has historically been some degree of institutional competition. There is a tradition, maintained by Lloyd Bentsen before me, that the Treasury Secretary and Fed chairman meet on a regular basis. So I now got together with Alan at least once a week for breakfast either at my office or at his, and before too long Larry Summers also joined us.

Our discussions ranged all over the place. Sometimes we were dealing with issues of crisis, such as Mexico or Asia. Other times we would be preparing for one of the several different international meetings of finance ministers and central bank governors or considering some issue expected to arise in Washington. But many times, we simply debated and explored issues about the U.S. and world economies. These meetings were a cross between a graduate seminar in economics and a policy-planning meeting, with bits of gossip thrown in. We were looking at intellectually complicated issues in the context of immediate, practical issues and decisions. While these discussions were serious, they could also be very funny—assuming you shared Alan’s taste for jokes about the yield curve.

One of the issues the three of us returned to again and again was the strong performance of the American economy. By mid-1996, the expansion was well established and still going strong. The growth rate was higher, and unemployment lower, than prevailing views would have said was possible without igniting inflation by putting upward pressure on wages and prices. People were throwing around the phrase “new economy,” suggesting that advances in technology had revised the familiar rules and limits. Some investors appeared to be falling prey to the timeless boom-era temptation to believe that the business cycle had been tamed, that companies would never fail in their earnings, and that the next economic slowdown would never come.

Yet amid such indicators of what Alan called irrational exuberance, real signs suggested that something had indeed changed for the better. With unemployment so low, a Fed chairman’s normal instinct would be to raise rates to prevent inflation. But there were no signs of increased inflation. The question was whether—as Clinton had intuitively argued in our internal discussions in 1994—the American economy could safely grow faster than during the previous few decades. Though there was no real evidence at the time, Clinton’s instinct turned out to be correct.

This apparent change in the so-called speed limit of economic growth strongly suggested that productivity growth—which had greatly slowed from the early 1970s through the early 1990s for reasons not fully understood—had now picked up again. Productivity increases work wonders on an economy, allowing faster growth without inflation. Understanding why productivity growth first faded and then apparently returned would help us estimate future growth and develop policies to promote it.

Most economists were initially skeptical about increases in productivity. But as time went on, Alan said that the data he was poring over didn’t reconcile unless productivity was substantially higher than was generally thought. One of Alan’s great strengths is his wide-ranging focus on data and his insight in drawing inferences from it. He’d show up at breakfast and ask what I thought about the latest railcar shipments of some type of wheat I had never heard of. “Alan,” I’d say, “I don’t know how I missed that figure in the paper, but I did.” He would have worked out a whole hypothesis around it. Greenspan was the first of the three of us to reach the tentative conclusion that productivity growth did explain the absence of expected inflation. That meant that the speed limit on economic growth was higher than we’d thought. Larry and I followed in agreement somewhat later.

In my view, a critical factor in the return of productivity growth was the restoration of sound fiscal policy. That helped catalyze productivity-enhancing investment by contributing to lower long-term interest rates, increased business and consumer confidence, and greater foreign capital flows into the country. Another key factor was advances in technology, which raised an interesting question. Europe and Japan had access to the same technologies we did in the 1990s but did not experience increased productivity growth. I think the explanation for the difference lies in a third factor: America’s cultural and historical disposition to take risks and embrace change. That inclination helped to explain why American companies invested much more heavily in new technologies than companies in other countries. A fourth factor, related to the third, was our more flexible labor market, which meant that companies could more readily benefit from productivity-enhancing investment, and our greater availability of risk capital. Japan and Europe were and are far less change oriented, more mired in structural rigidities, and shorter on risk capital.

A fifth factor, also related to our cultural tendency to embrace change, was our relatively low trade barriers. My initial belief in open markets was based on the standard comparative-advantage argument that dates from the great nineteenth-century British economist David Ricardo—that all countries will benefit if each specializes in the areas where it is most efficient compared to the others and then trades with the others. But Alan once made another point that never had occurred to me until he said it. The biggest advantage of free trade, he said, is competitive pressure within the United States from foreign producers. Companies have to become more efficient in order to meet competitive threats from outside our borders. Trade drives companies to reorganize and invest in pursuit of increased productivity. Conversely, Japan’s and Europe’s relatively less open markets protected companies and reduced their incentive to become more efficient.

But did these seemingly real changes in America’s productivity growth justify the tremendous rise in stock prices that was taking place? Again, Alan, Larry, and I reached a similar, tentative conclusion: something real was happening in the economy, but at the same time, the markets were probably overreacting to that real thing. That is what the great Austrian émigré economist Joseph Schumpeter said: almost every transformative, productivity-enhancing development also results in financial market overreaction. To me at least, that tendency seems grounded in human nature. Markets—which are expressions of collective behavior—tend to go to excess, in both directions, because human nature tends to go to excess.

Some of our continuing discussion was about what, if anything, people in our position could or should do to mitigate that inherent tendency to excess. As discussed earlier, none of us thought that economic policy makers should become market commentators, or that we could guide financial markets the way the Japanese and some previous administrations in this country had tried to do, by talking them up or down. I tended to believe, however, that regulatory measures might possibly have some effect in inducing investors to exercise discipline, and could certainly help protect the financial system itself. Disclosure requirements were obviously the place to start and were generally not controversial, at least in principle. But such mechanisms were like the old adage: you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t force it to drink. All the disclosures in the world won’t help if investors don’t care about risks or valuation. The boom in Internet stock prices in the late 1990s occurred despite full disclosure by companies with no real earnings.

Given the limits on what could be accomplished through disclosure requirements, I thought limiting leverage was also necessary both to constrain market excesses and to mitigate the harm they can create. For many years, banks and registered broker dealers had lived with capital requirements, and all investors were subject to margin requirements when they borrowed against stocks. But other kinds of financial institutions, including hedge funds, had no regulatory leverage constraints other than the margin requirements, if any, associated with the instruments they bought or sold short. My own view was that it wasn’t necessary to impose special leverage rules on hedge funds as a class of investor. I still think that is right, though as they become a larger and larger part of trading activity, policy makers may revisit that question, if some systemic risk is thought to be at stake. I do think, however, that derivatives, with leverage limits that vary from little to none at all, should be subject to comprehensive and higher margin requirements. But that will almost surely not happen, absent a crisis.

While economically useful under most circumstances for more precise risk management, derivatives can pose risks to the system when market conditions become very volatile. That occurs because of various technical factors that can cause derivatives users to suddenly need to buy or sell in the underlying markets to maintain appropriate hedge positions. With the truly vast increase in the amount of derivatives outstanding, it is at least conceivable that the effect on already disrupted markets could be vast. Some evidence of that potential appeared in the third quarter of 2003, when a rapid spike in interest rates changed the hedging requirements for mortgage-backed securities. The result was substantial exacerbation of that spike. Similarly, in 1987, some traders estimated that “portfolio insurance” selling of stock index futures added substantially to the October 19, 1987, stock market collapse. In a later speech at the Kennedy School at Harvard, Larry characterized my concerns about derivatives as a preference for playing tennis with wooden racquets—as opposed to the more powerful graphite and titanium ones used today. Perhaps, but I would still reduce the leverage allowed on derivatives substantially.

ANOTHER FOCUS OF MINE, which was less typical for a Treasury Secretary, was poverty and the distress of inner cities as critical economic issues. We set up, for the first time at Treasury, an office to focus specifically on these matters, headed by an extremely able and highly committed former Supreme Court clerk, Michael Barr. Such questions were often framed as debates about whether or not to help the poor. But, as important as moral and ethical issues are here, you don’t need to rely on altruism to make the case for tackling poverty. It is in everyone’s self-interest to reduce the societal consequences of deprivation. Poverty can foster crime and health care problems and in various other ways increase social costs and affect the lives of people who aren’t poor.

I learned very quickly, however, that advancing programs to help the poor—especially for minorities living in inner cities—was very difficult. Many people object to the idea of government assistance for the poor on principle; even well-designed programs meant to encourage work instead of welfare faced strong opposition. And the poor are not easily mobilized to advance their own economic interests. All sorts of groups could bring great pressure to bear when their concerns were at stake: environmentalists, labor, the elderly, business, and many, many others—but not the poor. You couldn’t count on a major letter-writing campaign in support of food stamps or inner-city job programs.

A significant accomplishment in this area by the Clinton administration was a large expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, a payment under the tax code to low-income working families to help lift them out of poverty. However, the EITC increase and other measures—though they had substantial impact—were not even remotely commensurate with the scale of the problem. But our ability to do more was limited. For our first two years, deficit reduction and health care reform were our highest priorities. For the next six years, control of Congress was in the hands of people who rejected most government involvement in these issues.

Nonetheless, real progress was made in combating poverty during Clinton’s years in office, largely because of the strength of the American economy. As unemployment fell back to levels not seen since the 1960s, the number of Americans living below the poverty line dropped steadily and gains by minorities were very strong. Births to teen mothers, which had been rising for forty years, finally began to fall. Welfare rolls began to decline significantly, even before the passage of a welfare reform bill in 1996. In New York, as in other big cities, the homeless population declined visibly. Clinton used to say that the best social program is a strong economy, though he always added that that wasn’t sufficient. He was right. Some people focus only on the economy and neglect the necessity of well-designed programs. Others focus on the programs and miss the central importance of a healthy economy.

Advancing new programs was not our only difficulty. Once we lost control of Congress, defending the effective programs already on the books, such as the EITC, became a major challenge. Without a large staff or a big bureaucracy, the EITC had made an enormous dent in the size of our poverty population by providing a subsidy to the working poor that was a powerful incentive for poor people to work full-time instead of getting by on public assistance. A group of conservatives in Congress, led by Senators Don Nickles (R-OK) and William Roth (R-DE), pointed to fraud in the program—people who weren’t entitled to the credit were receiving refunds—and we had to threaten to veto the 1997 tax agreement with the Republicans to prevent damage to the program. Fraud was a serious issue, significant reforms had been made, and we were strongly supportive of further reform. But the EITC was an excellent concept—Ronald Reagan, not a leading advocate of social programs, had strongly endorsed it because of its focus on work. And we insisted that the program be fixed, not cut back or thrown out.

Another program under attack was the Community Reinvestment Act, passed in the 1970s to discourage banks from the practice of “redlining,” or refusing to make loans in minority neighborhoods. The CRA required lending institutions, when seeking regulatory approval, to demonstrate that they had invested in their communities. This measure had greatly increased the availability and flow of credit in inner cities. After the 1994 election, however, we faced constant efforts to roll the program back in one way or another. One argument was that the CRA was simply a way for community and political groups to extort money from lending institutions. CRA almost surely had been misused in some instances—and we were again fully supportive of reforms. But, as with the EITC, we had to fight the all-too-common Washington strategy of using one rotten apple to proclaim the barrel spoiled. Our opponents seized on real issues about misuse in an attempt to eviscerate what had been, on balance, effective and valuable antipoverty programs. Happily, we were able to protect the CRA as well as the EITC. However, I’m not sure what would have happened absent our veto threat, and that is a sobering thought.

Welfare reform was the highest-profile issue in this area. In 1994, the administration had proposed legislation intended to replace welfare with work. But once Republicans took control of Congress, they passed a bill that was much more stringent. Inside the administration, feelings ran high. Some of us thought the bill Congress passed in 1996 was too severe and could create serious humanitarian and social problems. Others argued that the GOP bill was close enough to what Clinton wanted. Some believed that Clinton’s reelection prospects could hinge on his signing the bill.

The President convened a meeting of relevant members of the White House staff and cabinet. George Stephanopoulos, who was one of the first to speak, set the tone for the discussion. George was against signing the bill, but he said—as I think everyone in the room thought—that this was an agonizingly difficult decision. A veto could have a decisive impact on the 1996 presidential election, and if that happened, the consequences for people on welfare could also be far worse. I had not been much involved in welfare reform, but I shared George’s view that the President should not sign the bill. I felt strongly that some people on welfare are unable to work for reasons that are beyond their control, whether psychological, physical, or simply through a lack of work skills and work habits. This legislation didn’t seem to me to address any of that sufficiently. What’s more, the notion of cutting food stamps and other benefits to legal immigrants just seemed wrong to me. We needed more of a balance—not only stronger incentives for work, but also a greater effort at preparing and training people to work, and continuing to provide a true social safety net for people who couldn’t work.

I never knew if that was a real meeting or if the President had already decided to sign the welfare reform bill and was merely mollifying those likely to disagree by allowing them to be heard. In either case, airing the issue in this way was an example of shrewd governmental process. Getting everyone into the room and giving us all an opportunity to speak on an issue about which people felt so strongly minimized subsequent leaks and carping to the press. A couple of well-respected subcabinet officials did resign over Clinton’s decision to sign the welfare reform legislation. But had the President made his decision in a different way, the internal fallout could have been much heavier.

I never saw welfare as central to Clinton’s reelection, but I understood its larger symbolic significance and the political concern. To me, the central issue was the economy. The country’s continuing economic strength was obviously a powerful argument for giving the President a second term. Bob Dole, by contrast, seemed to me not to have a strong vision for his candidacy. I remember watching an interview with Dole on This Week with David Brinkley one Sunday, when I happened to be a guest. John Cochran asked him why he was running and what he wanted to do for the American people. Dole’s response focused on the politics and the polls, instead of where he wanted to lead the country.

AT THE BEGINNING of Clinton’s second term, I had to decide whether to stay or leave—possibly to become chairman of the Carnegie Corporation, a foundation involved in an enormous range of issues from education and civic participation to international security and development concerns. The President wanted to get together to discuss the issue and called me at the Jefferson one night at about 10:30 and asked me to come over. I was getting ready to go to bed but was happy to oblige. Since my Secret Service detail had turned in for the night, I went downstairs and walked over to the White House.

I went to the nearest gate, and the uniformed Secret Service officer inside the gatehouse asked if he could help me. “I’m here to see the President,” I said, mentioning that I was Secretary of the Treasury.

The guard gave me a suspicious look and sent me to another gate, where they recognized me and let me in. Then I went upstairs to the second floor of the residence, where Clinton and I had a long talk about what I was going to do, interspersed with an open-ended discussion of politics, our views of other people, and the policy issues that animated both of us.

Sometime after 2:00 X, I finally said, “Mr. President, I’ve just got to go home. I need to get up and be at work tomorrow.”

“Okay,” Clinton said. “Thanks for coming over.”

There was just one problem. I’d left home without my wallet.

“Can you lend me five dollars for cab fare?” I asked. “I’ll pay you back tomorrow.”

“Well, I don’t carry money,” Clinton said. “Maybe Hillary has some.” But she was already asleep, and he didn’t want to wake her up.

I suggested borrowing money from the Secret Service. So we asked them, and they immediately offered to drive me home.

There was another job possibility for me if I stayed. Leon Panetta was heading back to California and the President needed a new chief of staff to run the White House. Leon tried to convince me that I should take his place. For years, when I worked on Wall Street, I had always thought that being chief of staff to the President—which put you at the very core of the U.S. government and involved you in virtually all matters—would be the most compelling job in America. But now that this had—beyond my wildest imagination—become a real possibility, I knew I would pass.

While the job retained much of its appeal in the abstract, I didn’t think my being chief of staff would actually work, either for the President or for me. When you’re chief of staff at the White House, you can be an effective advocate for your own views, but you’re ultimately a personal assistant to the President and you’re deeply involved in all of his politics. I’d read some books about how previous administrations had functioned, and from them, as well as from working in the White House myself, I understood that an integral part of the chief of staff’s job was taking calls at one in the morning about whatever was on the President’s mind and dealing with complaints about newspaper articles he didn’t like. As Erskine Bowles said to me once, you may be the “chief” but you’re still “staff.” I couldn’t see being at the beck and call of anybody, even a President I liked and respected as much as I did Clinton. And after four years of commuting back and forth between Washington and New York, I didn’t want a seven-day-a-week, twenty-four-hour-a-day job. Finally, the position involved more immersion in politics than I wanted. At Treasury I could focus more intensely on a host of policy issues that I felt deeply engaged with.

So I took my hat out of the ring. But that left the question of who should be Clinton’s chief of staff. Erskine Bowles, who had resigned as Panetta’s deputy to return home to North Carolina and his financial career, had called to try to convince me to accept the job. We went through an Alphonse-and-Gaston routine: Erskine thought I should take it; I thought Erskine should do it. He didn’t want to come back to Washington. But Erskine has a strong sense of responsibility, and with Clinton leaning on him to return, he felt he either had to find someone else acceptable to the President or take the job himself. Somewhat reluctantly, Erskine agreed to become Clinton’s third chief of staff. But there was a price for me as well: Erskine wanted my chief of staff at Treasury, Sylvia Mathews, to become his deputy at the White House.

At the same time this was happening, I knew Larry Summers was thinking about leaving as well. He had been offered a high-level academic job and was also a leading candidate to become chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers. That caused me to think seriously about resigning. The Treasury Department was a team run by Larry, Sylvia, and me. Sylvia was essentially our chief operating officer; Larry provided a lot of intellectual leadership for what we did and played a big role in management. Both were superstars, with the kind of political savvy that’s critical in the ever-dangerous world of Washington, and, not unimportantly, we had a comfortable and good-humored relationship with each other. Perhaps I could have built a new team of equal effectiveness, perhaps not. In any case, my life at Treasury would be quite different, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to start all over again. I was mindful that I had had four good years and that in Washington things can change completely at any minute of any day. New York also held many attractions for me, including the prospect of being home again.

If, however, I could convince Sylvia or Larry to remain at Treasury, staying would become much more appealing. Sylvia was willing to stay and Erskine would have let her—albeit with great regret—but I didn’t want to hold her back from something she wanted to do. I thought the better alternative was to persuade Larry, whose importance to the administration was great and underappreciated, to remain in place. In government, as in business, the top person often has a complicated attitude toward the second in command. Some people think a powerful deputy will upstage them or make them look weak. I’d seen chiefs follow an instinct—conscious or unconscious—to prevent capable seconds in command from succeeding them. But I’d long had just the opposite view: having an extremely bright and skillful deputy greatly increased Treasury’s effectiveness. I also thought it made me look good, just as I thought that Gene Sperling’s prominence as my deputy at the NEC was good for the NEC and good for me. For two years, Larry and I had worked together as partners and shared credit for the department’s accomplishments. If I left before the end of Clinton’s presidency, I thought he would be the best possible choice to succeed me.

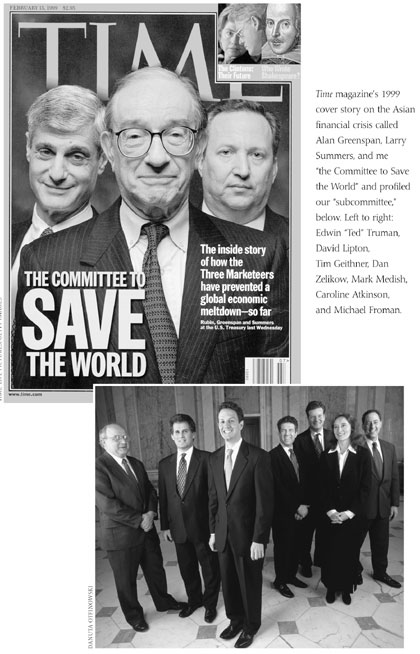

So I worked out a rather complicated proposal to make Larry comfortable with staying. I told him that my intention was to remain for two more years. I would try to get the President to agree that if I served two years into the second term, he would then name Larry as my successor—assuming, of course, that the President was still comfortable with Larry. If I left sooner, there would still be what lawyers call a “rebuttable presumption” in Larry’s favor. If I decided to stay longer, Larry could do as he saw fit. Larry said jokingly that he would understand if something dramatic happened that made my leaving after two years impossible. We both laughed at that. As it turned out, there were two such events: a global financial crisis and the President’s impeachment.

No guarantees were involved. I could decide to stay, or the President could simply say he wasn’t comfortable with Larry as Secretary for whatever reason. But we had an agreement in principle. For it to work, though, absolute confidentiality was essential. The only people who knew about this arrangement, as far as I knew, other than the President, Larry, and me, were the Vice President—whose agreement was requisite and readily given—Erskine, Sylvia, and Judy. For two and a half years, no hint of this understanding ever leaked—which was remarkable.

With Larry in place, I asked Michael Froman to take over Sylvia’s job as chief of staff. Mike had come to Treasury from the NEC staff some months after I had moved. He had a doctorate from Oxford, a law degree from Harvard, where he’d been an editor of the Law Review, a strong intellect, a deep interest in policy issues, and good practical judgment. Mike, like Sylvia, was straightforward, worked well with people, was highly effective managerially, and had an irreverent sense of humor—sometimes, alas, directed at the Secretary. One recent instance sticks in my mind. During the 2000 presidential campaign, my name briefly and implausibly surfaced as a potential running mate for Al Gore (along with all kinds of other people). Froman commented that it would be an interesting ticket: Gore and I would be on the stage fighting over who had to kiss the babies.

FOR THE TREASURY DEPARTMENT, the second term soon brought a crisis in one of the most basic functions of government: tax collection. The battle we fought with Congress—both Democrats and Republicans—over the Internal Revenue Service in 1997 stands in retrospect as a microcosm of much that I learned about Washington: the central importance of management; the complexity of managing effectively in government; the great difficulty in most circumstances of anticipating when matters will explode into political conflicts; the need to frame issues in ways that resonate; the power of the media to shape the political agenda and drive events; and, finally, the challenges of dealing with a political firestorm in the public sector.

Years before moving to Washington, I had clipped and kept an interview that Michael Blumenthal had given to Fortune magazine after resigning as Jimmy Carter’s Treasury Secretary in 1979. Blumenthal said that management tends to be taken much less seriously in government than in the private sector. Unlike CEOs, Treasury Secretaries aren’t remembered for how well they ran the place. Nonetheless, I had a strong interest in management and paid a lot of attention to management problems in the department. I was able to recruit Nancy Killefer, a partner at the consulting firm of McKinsey & Company, as assistant secretary for administration. Nancy brought great expertise and skill to issues such as the Treasury’s own budget and created flexible rewards for employees within the existing rules, as well as improving training and personnel practices.

Our greatest management challenge during my first two years at Treasury was our largest agency, the Internal Revenue Service. At that point, the IRS’s most widely publicized problem was an automation effort that in large measure hadn’t worked. The technology failure related to more general problems in the way the agency was run. Since the Second World War, the commissioner of the IRS had always been a tax lawyer, someone capable of navigating the labyrinths of a tax code that had grown to 9,500 pages. Larry Summers, who convened a working group to focus on the wayward technology project, convinced me that an organization of the IRS’s size, complexity, and importance needed a CEO experienced in management, not taxes. Larry and I spent a great deal of time at the beginning of Clinton’s second term interviewing candidates for this post. The person we liked best was Charles O. Rossotti, who had run a large Virginia-based consulting firm and was an expert in information technology.

We worked hard to address Rossotti’s concerns about the job, which included a fear that for political reasons we would commit ourselves to overhauling the IRS overnight. Rossotti knew what we knew: that the agency’s problems were vast and serious. Morale among employees was low and sinking lower. We were concerned that because of its antiquated technology, the system—which processes 95 percent of the revenues of the federal government—might simply break down.

While we worked quietly on this effort, others were becoming more vocal. Senator Bob Kerrey had set up a commission on restructuring the IRS, and its hearings became a forum for using complaints against the IRS to argue against the progressive income tax itself. The House majority leader, Dick Armey (R-TX), came and testified in favor of his flat tax. The conservative activist Grover Norquist, who was chosen as one of the Republican members by Newt Gingrich, tried to turn the hearings into an investigation of whether the IRS had politically targeted conservative organizations such as the Christian Coalition—a baseless accusation. Around that time, bumper stickers that said X began to appear.

Senator Kerrey tried with mixed success to resist the effort by some conservatives to turn the hearings into an antitax, antigovernment platform. He also used it to promote one of his own favorite ideas: the separation of the IRS from the Treasury Department. Despite my regard for Kerrey, a man with enormous personal charm, this proposal appeared to me to be monumentally wrong. The notion, which reappears periodically, of breaking out discrete parts of government into independent units reporting to boards, seems to me to be a formula for less accountability and hence less effective government. In this case, a board would never have the knowledge or the continuity of focus that Treasury could have. And unlike a private-sector CEO—the argued analogy—a freestanding IRS chief wouldn’t have to worry about his share price or stockholders. Kerrey and I had some fairly contentious meetings in which I failed to persuade him of my position and he failed to persuade me of his. I felt strongly enough to recommend that the President veto the reform legislation that Kerrey was planning to introduce on this issue.

With Rossotti signed on and the White House supporting our position on an outside board—although not to the point of agreeing to my veto recommendation—we began to feel that we were getting a handle on the IRS. It was far from my mind during our trip to China in September 1997. I was walking through Tiananmen Square late at night with Mike Froman and Bob Boorstin, who had moved from the White House to Treasury to advise me on political and communications issues, when Linda Robertson, by then our assistant secretary for legislative affairs, reached me on a cell phone to say that a storm had broken out in Congress. What flashed through my mind was a warning signal I hadn’t recognized. Back in 1995, soon after I’d been confirmed as Treasury Secretary, I’d appeared on This Week with David Brinkley. Brinkley’s first question had been about complaints he was hearing about the IRS. I’d been surprised that this legendary Washington journalist would waste valuable interview time on such an obscure topic, and I’d fobbed off the question with a kind of nonanswer. Now I thought that Brinkley might have had his finger on the political pulse after all.

We knew, of course, that Senator William Roth, chairman of the Finance Committee, was going to hold hearings to look into IRS abuses. But we had no idea of the media feeding frenzy that would develop. Opponents of the income tax had found—or created—a great political opportunity. Roth’s staff gave an advance preview of the worst horror stories they had gathered to 60 Minutes, which presented them on the Sunday before the hearings in a highly dramatized way that was lacking in balance. Clearly, the IRS had real and serious problems. But the 60 Minutes presentation was misleading. Shortly after that, Newsweek published a cover story about the IRS that was also inflammatory.

Over a period of three days, the Senate Finance Committee had IRS employees testifying in hoods and people hidden behind partitions speaking into voice distortion machines for protection against possible retribution. We didn’t even know who these people were. Those on the committee who were truly interested in fixing what was wrong with the IRS—as opposed to demonizing it—had no way to bring balance to the hearings.

We couldn’t respond to the horror stories even if we had wanted to. A federal law forbids any release of private taxpayer information, unless the taxpayer waives his right to sue for violation of privacy. Such waivers ought to have been a condition of this sort of testimony before the Senate Finance Committee, but neither the committee nor the media required that of witnesses. As a result, the public had no way of knowing whether people who claimed to have been so abused were telling the truth.

In a more reasonable perspective, the IRS was a largely effective tax collection agency with some very real failings. One problem was that it had too much of a law enforcement mind-set and not enough of a customer-service mentality. But many people simply refused to acknowledge that law enforcement was necessary for our system of voluntary compliance to work. Some critics, such as Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA) and Representative Rob Portman (R-OH) were sincerely concerned with making the IRS more taxpayer-friendly. But throughout the hearings, others tried to turn a few abusive episodes into a misleading impression about the IRS as a whole. No one cared that 205 million returns were processed every year without any known dishonesty or corruption. Once the idea took root that the IRS was an out-of-control agency gratuitously abusing taxpayers, reason and proportion could not be brought to the issue. Republicans, Democrats, and the media piled on, without any serious focus on the larger picture.

I soon realized we had no way to effectively respond to allegations, let alone restore balance, in the midst of a political firestorm. David Dreyer told me that no one would listen to anything I said on the subject unless the first words out of my mouth were “There are problems at the IRS, and we’re committed to reform.” But this wasn’t like Clinton and the balanced budget or Bill Lynch refusing to criticize Jesse Jackson at that dinner in New York. Even with that admission, which I made constantly, no one was interested in a balanced view of the IRS. I could have hired a marching band, and no one would have paid any attention.

The problem is that when one person is abused—and some people really were—a government official who tries to paint a more complete picture simply won’t be heard. When a taxpayer gets up and tells a story about IRS agents acting like thugs, it wipes out everything else. Saying that the overwhelming preponderance of the 102,000 employees at the IRS are conscientiously applying a code of incredible complexity, and that some error, even some wrongdoing, is inevitable, gets absolutely no traction. The most courageous U.S. senator couldn’t bring balance to such a discussion with the whole process lined up against him in this way. He would simply be overwhelmed by a bad process on its way to creating flawed legislation.

What I never understood in any of these firestorms is why some enterprising reporter didn’t pursue the other side of the story out of self-interest. Someone attempting to be the voice of reason in a lopsided debate would seem well positioned to get onto the front page or appear prominently on television. Eventually a few journalists did write more objective articles about the IRS. But for the most part, the coverage seemed utterly one-sided, with at best an offsetting paragraph or two buried deeply in articles with sensational headlines.

In private, I did try to make the point about the inevitability of error. At one meeting with Senator Roth, he said that the IRS should have “zero tolerance” for mistakes. I’d say, “Bill, I don’t know of a single day of my life with zero errors. There are a hundred thousand people at the IRS—how are you going to do that? I’ll bet even you make mistakes sometimes.” Roth laughed and said, “It’s true we all make mistakes.” But he didn’t alter his course.

With these hearings and the surrounding media coverage, IRS reform legislation became veto-proof. When I got back from China and met with Erskine and a few others in the chief of staff’s office, everyone there agreed that vetoing the GOP bill made no sense. But with the Democratic leadership in Congress signaling support for a law that was sure to pass and no threat of a presidential veto, we had little with which to negotiate. However, the Treasury team decided to persist. I steeped myself in the technical details and functioned almost as a senior staff person in working with congressional members and staff to try to improve the bill. Despite our lack of leverage, we were able to make a significant contribution to the legislation in the end, due in large part to the credibility that our prior work on reforming the IRS gave us with those legislators who took the problem seriously. In particular, after the political uproar had died down, I was able to work with the two House members most involved with this bill—Republican Rob Portman and Democrat Ben Cardin of Maryland—in a refreshingly non-political way on the key issues. The other congressman I remember most vividly from that episode was Democratic Representative Steny Hoyer, who supported us on principle at a time when few others were willing to do that.