Once the bags of roasted coffee are shipped to joe, our baristas undergo an intense learning experience as they familiarize their palate with the flavors of the individual coffees. Since we rely on freshness and seasonality, our origin coffees have a quick turnover. The Brazilian you loved on Monday may be replaced with a very different Kenyan by Friday. Throughout the ongoing transition of getting what coffees are in season, Amanda Byron leads the cupping sessions and educational seminars for the joe staff as well as directs our classes, which are open to the public at our in-house coffee university.

When cupping and tasting, we look for complexity, richness, and perfect balance in the brew. Complexity occurs when the taster identifies diverse flavors commingling, richness might be identified as the roundness of the body, and balance is the comprehension of all of the desired elements required for a specific blend. These characteristics come together in a brew that is 98 percent water and 1 to 2 percent flavor and color.

When combined with hot water, about 28 percent of coffee is soluble; however, we do not want to leech out all 28 percent as this would make the brewed coffee acrid and bitter. Precise brewing will only extract about 22 percent of the coffee solids, leaving the bright, sweet, caramel-like cup that we desire. The actual percentage determines what is usually known as the “strength” of a cup of coffee.

Cupping takes practice. The first few attempts can be awkward, but once you get into the swing of it, cupping can be a lot of fun as well as educational. Much like wine tasting, it is an old process that has strict rules and regulations that are followed throughout the world. The coffee to be cupped is ground and carefully weighed. At joe cuppings we use 12 grams of coffee, ground fairly coarse in a 7-ounce bowl or cup.

The first job is to experience the dry aroma of the coffee. Next step, add hot water, just off the boil, to the top of the cup, letting it brew for four minutes. Take a moment to experience the aroma of the wet grounds, then “break the crust.” This is done by pushing a spoon into the grounds (which have formed a crust) carefully to the back of the cup. The cupper will place her nose right above the crust to get the full measure of the aromatic characteristics trapped just under the surface of the coffee.

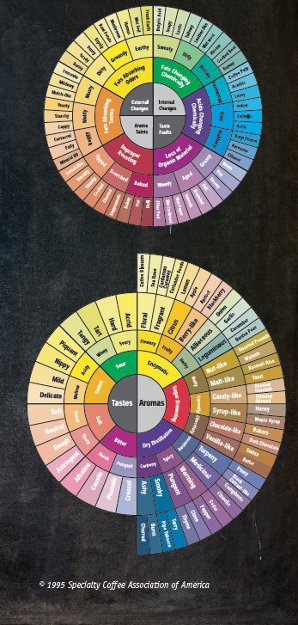

The Specialty Coffee Association Of America

FLAVOR COLOR WHEEL

After the crust has been broken, the grounds then steep for anywhere from another 5 to 10 minutes depending on how much the cupper wants the coffee to cool. After skimming the foam and minimal grinds from the top of the cup, tasting begins as small amounts of coffee are taken in with loud, noisy, inelegant slurps. This sounds easy enough, but it takes time and practice to slurp properly, allowing the coffee to be sprayed across the entire palate. Once tasted, the coffee is usually spit into another cup so as to avoid overcaffeination. Interestingly enough the flavors change and intensify as the coffee cools. It is often easier to discern all of the qualities sought when the coffee is lukewarm. In fact, it is standard practice to first taste the coffee when it is hot, but not scalding, and then go back for another taste when the coffee cools.

Although each cupper will find her reaction to a specific coffee to be very personal, with the aromas occasionally bringing up long forgotten memories, there are some generalizations that can cover the primary sensual experiences of coffee cupping. On the following pages we will attempt to give a brief overview of the various fragrances and aromas, tastes, and mouth-feel that predominate when cupping specialty coffees. These will give you the base for cupping your own freshly brewed coffee.

FRAGRANCE/AROMA

The fragrance is defined as the aroma you inhale after the beans have been ground and placed in the cup. This is your first sense of the flavors you might experience in the finished cup. The aroma follows as it comes from the smells that arise once the ground coffee has been covered with hot water. Breathing in these complex aromas furthers your sensory expectations. Although not limited to these varying bouquets, the following are among the many aromatic sensations you might experience. Some of them are very pleasant while others might be off-putting. Some of these associations are only experienced by a professional taster, and we, as a group, have not come close to familiarity with all of them. When a seasoned buyer or roaster cups, his refined palate can judge when, if, and how the off-putting aromas will impact the finished cup.

FOOD ASSOCIATIONS

Herb/Grass: Sensations include all fresh-cut herbs, especially parsley, tarragon, and basil, freshly mown grass or hay, bursting spring green foliage, dewy grass, the air of a bright spring day.

Fruit: Berries and citrus fruits are the most common aromas sensed. The sweet, juicy aroma of mashed ripe berries (usually a specific type) is a frequent denominator, while both the smell and taste of citrus, particularly the sweeter fruits, often follow from the fragrance through to the final taste.

Chocolate: All manner of chocolate—from cocoa powder to unsweetened baking chocolate—is frequently found in the fragrance and aroma of specialty coffees. When milk chocolate is smelled, the coffee is often described as simply sweet-smelling.

Spice: Generally only those spices that are termed sweet, such as cinnamon, cloves, allspice, and cardamom, are found. Although the scent of savory spices can be noticed, it is usually described specifically, such as black pepper or ginger.

Caramel: Caramel-like is often the first descriptor a cupper will experience, but it is the aroma of perfectly caramelized sugar that the cupper is seeking. The aroma of burnt sugar, though, would be an unpleasant note throughout the coffee.

Cereal: Both the aroma of raw or uncooked grains as well as cooked or roasted ones, such as oats, wheat, or corn, can be noticed. For professional cupping, this particular fragrance/aroma has been grouped with malt and toasted bread aromas into one category, a grain-type aroma.

Toast: The aromas sensed include freshly baked sweet breads, toast, and warm out-of-the-oven yeast-based breads and rolls.

Malt: The fragrance and aroma range from warm biscuit-like to deep earthy grain flavor; sometimes even the defining malt characteristics of beer are sensed.

Nut: The all-encompassing aroma of fresh and/or roasted nuts often defines specialty coffee. However, any note of rancidity or bitterness indicates a poor quality coffee.

Wine: Everything about the sensations of drinking a fine wine—aroma, flavor, body—comes together when this fragrance/aroma is experienced. This generally indicates fruity qualities and a refined acidic note in the finished cup. However, at the opposite end, the fragrance/aroma should not be one of sour fermentation.

Burnt food: The dark, earthy, rather unpleasant aroma when foods are overcooked may be experienced.

Rancid fat: The aroma may seem like the oxidation of nut and animal fats. This aroma is not necessarily a sign of deterioration in the coffee, but of a general strong note.

Rotten food: The aromas emanating from decaying vegetables or vegetation or other non-fat products again can indicate strength rather than deterioration in coffee.

NOTES OF NATURE

Floral: The cupper may sense the bare scent of almost any flower, but often sweet flowers such as jasmine or honeysuckle, occasionally rose. Of all the fragrances and aromas, this one is rarely experienced in the finished cup.

Woody: Aromas include damp forest floor, dry wood, wooden barrels, even old cardboard, particularly if wet.

Dirt: Freshly dug earth, humus, damp soil, a soaking, watered garden may all be experienced, but a moldy, earth-like aroma is undesirable.

Tobacco: The aroma should be of fresh tobacco, only.

Burnt wood: The fragrance/aroma of smoke from burning wood often indicates a bean that has been overroasted.

Animal: The general smells of an animal—wet fur, a just-raced horse, leather, dried hides—may be sensed. Again, this is used to describe intense coffee notes and is not considered undesirable.

OTHER ASSOCIATIONS

Medicinal: The fragrance/aroma may be of a just-opened pill bottle, a hospital corridor, a doctor’s office—all familiar, but not necessarily pleasant associations.

Rubber: A cupper may sense the smell of burning rubber, hot tires, and rubber bands. Interestingly, this aroma is required in some coffees and, as such, is not considered undesirable but can be a characteristic of darker roasted coffee.

Ash: This is a scent one normally shies away from—a dirty ashtray, a smoker’s fingers, or the accumulation of ashes in a fireplace. Again, this is not an undesirable aroma but one used to indicate the degree of roast.

TASTES

Acidity comes from the hint of brightness you experience with a sweet, clean coffee. It is acidity that offers the most captivating floral or fruit flavors. The perception of high acidity in some coffees is correlated with the characteristics of citrus fruits. In a specialty coffee, the perceived acidity can range all over the map—from intense to almost nonexistent, from soft and round to irritable, from sophisticated to untamed; you name it, acidity has been so described. Acidic notes are best experienced once a coffee has cooled to lukewarm.

Acid: This is not the unpleasant taste often associated with sour acids, but a quite refined sharp, agreeable flavor that frequently exemplifies coffees from specific regions.

Bitter: This is one flavor that the roasting and brewing techniques impact. It is one of the primary taste notes in coffee that is identified by a mixture of quinine, caffeine, and particular alkaloids.

Saline: This is another premier taste that is identified by sodium chloride and other salts.

Sour: When tasting, these notes are often confused with the more pleasing acidic notes. Sour notes will be much more bitter and sharp, rather like vinegar, and can be the result of fermented coffee.

Sweet: This is one of the best and most desirable tastes, used to define any coffee that has absolutely no off-flavor. It is the one characteristic that often separates great coffee from good. It is often found in partnership with acidity and, in turn, creates the perfect balance necessary to mellow out the intense acid. It brings forth the sweet notes of caramel, fruit, and/or chocolate.

BODY OR MOUTH-FEEL

This is simply how the coffee feels when sipped and rolled on the tongue. It is often the most difficult trait for beginning cuppers to grasp. It is best to think of it as the weight of the coffee and the texture you feel in your mouth. A good example would be the varying weights of heavy cream, whole milk, and skim milk on the palate. Great specialty coffee should leave a lasting fullness on the palate, never a thin, watery feel.

FLAVOR

This is the complete sensation of all of the elements of a particular coffee coming together in the mouth.

FINISH

Great specialty coffee has a pleasant, lingering aftertaste. This is the lasting impression and is often far more memorable than the first sip. The perfect finish is one that is sweet, free of imploding elements, and lasts for at least ten seconds after the coffee has been swallowed. Most of all, the finish should produce the defined flavor of the coffee. If the coffee leaves an unpleasant, astringent aftertaste and a dry mouth, it is not good coffee and should be discarded. And, if the coffee is neutral in flavor and leaves no aftertaste, it would be deemed unacceptable.

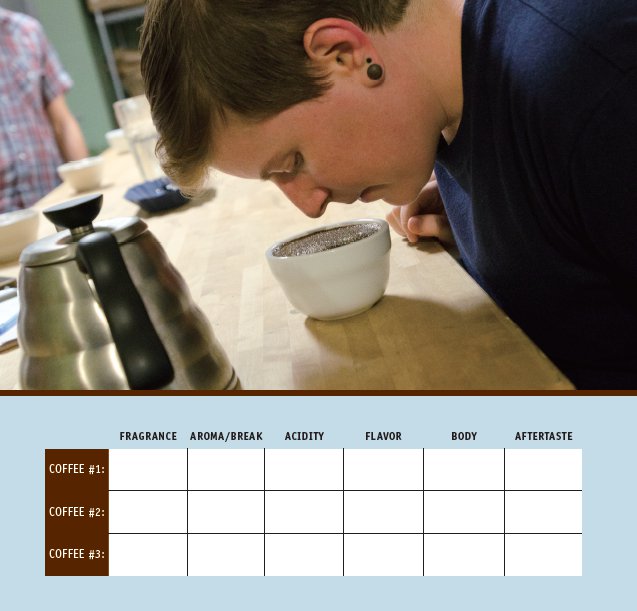

COFFEE CUPPING CHART

The chart opposite is a basic cupping chart and can be used by the individual taster to enter his or her analysis of each of the defined coffee characteristics through the specified segment of the cupping process. This process will be fully described and illustrated so that the reader can “cup” at home to determine the quality of purchased beans.

Over the past few decades, almost twenty thousand studies have investigated the benefits and/or drawbacks of coffee consumption. Whether such news impacts the buying and brewing habits of joe consumers, we can’t say, but it has been found that coffee does contain a number of excellent health perks while coming with a few health warnings. Because of the antioxidant compounds in coffee, moderate coffee consumption can aid in the reduction of risk of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and stroke, while frequent coffee drinking can lower the risk of diabetes, prostate cancer, and liver disease. In fact, it seems that the more coffee you drink the less your chance of contracting liver cancer, although just the opposite occurs with heart disease as it is believed that too much caffeine combats the effects of the antioxidants. The warnings center on the consumption of too much caffeine, resulting in a “caffeine buzz” that can disturb sleep and concentration as well as cause anxiety and irritability. Although doctors and studies note that pregnant women can consume up to 300 milligrams of caffeine a day, roughly one large cup or three espressos, at joe we find that a lot of our customers who are pregnant or nursing switch to decaf for the duration.

FRAGRANCE: The smell of beans after grinding

AROMA/BREAK: The smell of the coffee after water is added

TASTE: The flavor of the coffee

BODY: The feel of the coffee in your mouth

AFTERTASTE: The vapors and flavors that remain after swallowing