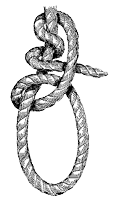

Midshipman’s Hitch

Lucky rose and made his way past the row of closed doors lining the narrow, whitewashed hallway. He descended the steep staircase, noticing again the smell of Island food. It was chachupa, a Cape Verdean dish of corn, beans, chorizo, and sweet potato. Pa had introduced him to the delicacy last spring when the Nightbird had stopped to provision and recruit crew on the tiny rock island of Fogo.

Maybe if he fetched water for the crazy woman, she’d give him a ration. Or should he even be thinking about staying there long enough to eat? He reached into his pockets and pulled them inside out. Tiny bits of lint drifted to the floor, and that was all that remained. His coins were gone. “Hell’s bells!”

“Missing something?” He hadn’t noticed that Mrs. Cabral had come down the stairs behind him.

Lucky eyed her suspiciously. There wasn’t a single member of the Nightbird’screw who hadn’t had his pockets lightened in his sleep by a land shark, the name sailors used for an unscrupulous landlord. One thing was for sure, either the one-handed woman or that cutthroat Fortuna had his bag, his gear, and everything he owned in the world but the clothes on his back. Not for long, he thought.

“Where’s Fortuna?” he asked.

“Said he’d be back in three shakes. Why?” She regarded him with narrowed eyes. “If you’re thinking you can light on out of here, you can forget it.”

“I’m a fish flapping on the deck. With my duffel and money both gone, I’ve no choice but to stay on a bit and try to get ’em back.”

She nodded. “Them’s wise words, boy. No use wasting time fighting the current. Sometimes you have to sail north to get south.”

“My husband was a boat steerer,” she added, as if reading his thoughts. “Get me that water and I’ll serve up some stew.”

He picked up the tin bucket and passed through a heavy planked door into the yard.

Divided into quadrants, with the water pump occupying a prominent spot in the middle, the back garden of Mrs. Cabral’s boardinghouse would make even the most particular of shipmasters proud. Neat rows of cassava and squash vines, just starting to bloom, snaked out from the dark earth to Lucky’s left. To the right, cabbage and turnips grew with young corn plants that came to his knee. At the back of the property, where a decrepit wooden fence separated the yard from the one beyond, beanpoles had been artfully arranged in a crisscross pattern. Overhead, an arbor made of driftwood and barrel stays held an enormous grapevine with new light-green tendrils reaching up to the sun.

The smell of soil, which usually made him feel claustrophobic and uneasy, was instead comforting in its heady richness. Lucky knew more than he cared to know about vegetables. As the cabin boy, he’d loaded bushels of them onto the Nightbird whenever they stopped in port—and then spent countless hours peeling and chopping them in the galley.

With a jarring shriek, a gull lighted on the back fence.

“Oh, it’s you…” He recognized the brown head against the white body immediately. He owed this bird for trying to belay Fortuna with a heavy load of dung. “You’re smart as a Philadelphia lawyer.” Lucky doffed his cap. “I think I’ll call you Delph.” The gull cocked its head and called in a way that seemed to indicate agreement.

“What’s keeping you?” Mrs. Cabral called.

“Coming.” He hurried along the smooth path toward the house. “Adios,” he said to Delph over his shoulder.

Within minutes, Mrs. Cabral had served up the promised afternoon meal and disappeared with the bucket of water. Though he felt a bit disloyal to old Enoch, the galley cook on the Nightbird, Lucky savored each mouthful.

“Where’s Mrs. Cabral?” Fortuna asked, entering the kitchen and taking a plate from the sideboard. He filled it using a ladle from the pot and took a seat next to Lucky at the table.

Lucky drew his arms in closer to his body. The mouthful he chewed suddenly lost all its taste. When he swallowed, a piece of potato stuck in his throat. “Washing the floor,” he managed to say after finally getting it down.

Fortuna took a bite of stew and then another. Soon his plate was empty. He stood and pushed back from the table, wiping his mouth with his sleeve. “Let’s go,” he said.

Lucky eyed him over his second plate of chachupa. It had been a wise decision to carry water for Mrs. Cabral. The meal was the best he could remember. Though the food had improved his mood considerably, he wasn’t ready to give quarter to Fortuna.

“Where’s my things?” he said.

“I’m keeping them for you. Not that they’re worth saving. A moth-eaten wool cap and jacket—”

“Those’ve seen me around the Horn in some dirty weather!” Lucky protested.

“Don’t worry, I haven’t tossed them on the rubbish pile.”

“What about my rigging tools and money? You have no right to keep me from my ship and trade!”

“I have every right. Everything you own is mine. For the next four years, you are mine. That’s what the law says.”

“If it’s what the law says, why’d you have to grab me on the street?” Lucky asked.

Fortuna laughed. “Didn’t want to take the chance of you slipping away. If you’re anything like our father, you’re an expert at that.”

“Why’d you wait ’til now to make yourself known?”

“Before our father died, I had no claim on you.”

Lucky stared at the plate in front of him, his appetite gone.

“So you see, you have no need for rigging tools.” Fortuna nodded toward the door. “Dinnertime’s over. We’re due at the mill.”

Lucky turned the words over in his head. He needed fresh air and a chance to think.

“Know this,” Fortuna said. “I’ll send you to blazes if you don’t do as I say. I’ve already started to sour on your talk of the sea.”

Lucky rose and followed him down the hallway that led to the front of the house. A tall hall tree guarded the door, its long arms reaching toward the ceiling. An assortment of hats and caps dangled from hooks like apples. On the lower branches hung a multitude of dark-colored coats and capes. The bottom held a stand containing several walking canes and parasols.

“Whose are these?” Lucky asked. It appeared that at least thirteen souls must have come for tea.

“Boarders,” Fortuna said.

“Where are they?”

“Gone whaling.” He took Lucky’s sleeve and pulled him through the door onto the outside landing. “Or dead.”

Lucky wanted to know more, but his half brother was down the stairs and on the street before he could ask. He followed, but turned to take a look at the outside of Mrs. Cabral’s house. Its clapboards had once been whitewashed, but time and the elements had left the building looking as if it had been dipped in the ocean and only white salt residue remained in the crevasses.

The yard in front was neatly swept, though, and as he turned to catch up with Fortuna, Lucky thought he saw a movement in one of the front windows.

“Is this the place they call Little Fayal?” he asked.

“You’ve never been here?” Fortuna said. “I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that ole Jack didn’t keep with his own.”

“Sailors do keep with their own,” Lucky said. “We bunked at the Mariner’s House.”

They passed three dark-skinned children, one leading a bedraggled-looking dog by a rope. They stopped talking as Fortuna and Lucky moved closer, and kept the dog out of Fortuna’s path.

“Among our people, children are respectful to their elders. You would do well to learn this quickly.”

“I’m respectful,” Lucky said. He could feel his color rising. “Whaleman’s commandment #6 is ‘swear, but never in front of a good woman.’”

Fortuna let out an exasperated sigh. “When we get to the mill, just keep your mouth shut.” He glared at Lucky. “And tuck in that silly scarf! That gets caught in the machine and it’ll wring your fool neck.”

Lucky bristled at the insult to the only thing he still had left that was Pa’s. He tucked it into his shirt. No use arguing with Fortuna. Instead, he’d try to get on the man’s good side. Maybe that way Lucky could find out where the cussed swindler had stashed his goods.

“Look here,” Fortuna said, pointing down the street they had just crossed onto. “This is Water Street. You stay on it ’til you reach the train tracks, then go north two blocks to Third Street. Turn right on Third, and you’ll be at the mill.”

“I know my way around this part of the city. You don’t have to tell me how to get there.”

“You know your way around the waterfront, you little wharf rat. I’m telling you that these are the only thoroughfares you are permitted to travel. If I find you’ve been elsewhere, I’ll row you up the salt river. Understand?”

“Jeesh,” Lucky said.

Fortuna grabbed his ear. “And listen good. I’ve put the word out on you among the merchants and ships’ agents. It’s on the dossier that you’re underage and lack my permission to ship.” He twisted Lucky’s earlobe viciously. “Hear?”

“Oyyy. Yes.” Hell’s bells! He’d been counting on Fortuna being unwise to the ways of maritime trade. How’d he found out about the dossier? This would make his lot much harder.

As they neared the corner of Union and Water streets, the sidewalks became more crowded. Here beat the heart of the shoreside district, where Lucky had passed earlier this morning, full of anticipation and blissfully unaware of Fortuna.

Could it have been just a few hours ago? He scanned the faces in the crowd for someone he knew. But they’d all gone. Away on the ship, full up with supplies and hope, into the wide Atlantic. It could be three years or more before the Nightbird returned. Never mind, Lucky told himself, he’d just have to find a way to catch up with her.

“Read and ponder, my good people,” a man called from a street corner in front of them, “The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.” He held a stack of handbills, which he pressed on passersby. “A law that disregards personal liberty, tramples on the Constitution, and makes criminals of good Christians!”

Fortuna quickened his steps to get past.

“You sir,” the man said, reaching for Fortuna’s elbow. “Are you already a member of the Abolitionist Society?”

“Why would I be?” Fortuna glared at him.

“As a colored man, I’d think this would interest you.”

“I’m Cape Verdean,” Fortuna said, his voice low and menacing. “What use would I have for your fool society? Besides, I think personal liberty is overrated.” He grabbed Lucky by the ear. “Isn’t that true, brother?”

Lucky shook off Fortuna’s grasp.

The man’s face turned red. “The slave catchers don’t care who you are or where you came from, my good man.” His voice rose to include the gathering crowd. “You’re colored, and as such could be kidnapped and forced into a life of slavery.”

Fortuna grabbed the abolitionist by the collar.

Like me! Lucky wanted to shout.

“You can shout from street corners if you’ve got nothing better to do,” Fortuna growled in his ear. “But some of us work for a living.” The man’s eyes widened. “Do not bother me or my brother again.” Fortuna gave the abolitionist a shove and the stack of handbills fell from his hand and scattered. Fortuna stepped on several of them as he charged down the street.

The hope Lucky’d felt evaporated like a raindrop on tar. What had he been thinking? Laws made by a bunch of fancy landlubber politicians in Washington didn’t have anything to do with him. Bunch of hot air in slack sails.

“Someday,” Fortuna said, his mood seemingly improved by his dispatch of the abolitionist, “my name will be known on these streets.”

“These streets aren’t so fine,” Lucky said. “And Pa’s name was spoken in ports far off as Valparaiso, the jewel of the Pacific.”

Fortuna glared down at him. “And everywhere else he owed money.”

“No! Pa was known as far abroad as the Galapagos Islands, where they have birds with feet bluer than a May sky.”

“Probably talked a blue streak of lies.”

Lucky bit back the urge to defend his father. He gritted his teeth and kept walking. One way or another, he’d get Pa’s knife back.

The waterfront was so close he could smell the whale oil.

Fortuna pointed at a plaque outside one of the bank buildings. “Lucem Diffundo,” he read out loud. “Do you know what that means?”

Lucky shook his head.

“I pour forth light.”

Fortuna poured forth something, but it surely wasn’t light, Lucky wanted to reply. Best keep it to himself.

“Someday, I’ll have my share in all this.”

This was too much. Lucky couldn’t hold back the wave of fury. “Any share you’re able to wrangle was born on the backs of men like Pa,” he said. “They made this port rich on whale oil. What’ve you ever done?”

“Don’t forget your own scrawny back,” Fortuna said. “You’ll have a part in the getting of my fortune.”