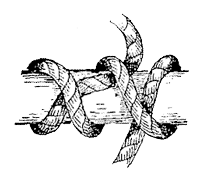

Rolling Hitch

Fortuna gave the bed frame another push, his lip raised in a disgusted sneer. “Time to go.”

I thought the boy should sleep in this morning,” Mrs. Cabral said as she scrubbed the kitchen floor, her stump hand holding the bucket still while she wrung the cleaning cloth. “There’s food wrapped up by the door. Enough for you, too, Fernando.”

Fortuna grunted his thanks, grabbed the bundle, and stepped outside. Lucky followed, not at all optimistic he’d see his share.

“You’d better not be so lazy you lose your place with Mrs. Cabral,” Fortuna warned as they walked down the street. “I couldn’t believe my luck when she said she needed some help. Got a handsome deal, too. If you foul it up, you’ll be a long time regretting it.”

“I won’t,” Lucky said and kicked at a weed that grew along the side of the street.

When Antone and some of the other mulespinners appeared, Fortuna hurried ahead to meet them. He threw a chunk of bread back and Lucky caught it eagerly.

Lucky took a big bite, happy to be rid of his guardian.

A moment later a loud squall let him know Delph was about and keen to share his breakfast.

“Go get yourself a clam,” he called to the hovering bird.

“Morning.” Daniel appeared beside him.

“Where’d you come from?”

“I board over to Mr. Bush’s, just there.” Daniel pointed at a large shingled house on South Water. “He’s one who takes in fugitives.”

“There are others?” Lucky asked.

“Plenty. I’m more blessed than most, though, ’cause I got trained as a mulespinner back in Alabama. Here, it’s a job wouldn’t normally be open to someone like me. But I’m good at it. Once Mr. Briscoe saw what I could do, he hired me on the spot.”

“Don’t know how it could sit right with you, doing the same thing you did as a slave.”

“It’d be wasteful for a man not to use the skills God has seen fit to give him.”

“Do you sometimes feel like you’re back in that mill in Alabama? Do you forget you’re free?”

Daniel looked at him as though he’d just blown a spout of water from a hole in the top of his head. “Even the air tastes different to a free man.”

They walked on awhile in silence.

“Tell you what does bother me,” Daniel said.

“What’s that?”

“Mills making fortunes on the backs of slaves.”

“I thought I was the only one who didn’t collect a wage. They pay you, don’t they?” Lucky asked.

“Sure, they pay me. But where do you think those bales of cotton come from? Slaves! Do you know what happens to a back bent over day after day, year after year?” Daniel stood rigid. “It won’t straighten anymore. When I heard about the trouble they had at the abolitionist meeting over in Lowell, I’d have liked to show ’em a few of those bent spines.”

“What sort of trouble?” Lucky wanted to know. He wasn’t looking forward to meeting Emmeline at the meeting tonight; best know what to expect.

“They threw stones at the abolitionists! Stones!” Daniel’s voice rose in indignation.

“Where’s Lowell?” Lucky thought he’d heard of it, but he didn’t concern himself with landlubber places.

“A day north of here. Lots and lots of mills.”

They’d closed some of the distance between Fortuna and the others, who looked back at them and jeered.

“They don’t like me, ’cause I can spin faster and more than they can. I meant it when I said I’d help you learn the ropes.” Daniel spread his arms, palms extended.

“Era negro de quintal de nha pai,” Antone said in a loud voice. The men around him laughed.

Lucky looked over at Daniel, hoping he didn’t understand Portuguese. Antone had just said, “He’s a slave on my father’s plantation.” But Daniel walked on, intent on the pattern of cobbles on the street.

“I don’t let the others get under my skin. I’ll meet my reward in the Hereafter,” Daniel said, but when Lucky looked over, the line of Daniel’s jaw showed his teeth were clenched.

“It’s the herenow I’m interested in,” Lucky replied, taking another mouthful of bread.

The gull swooped and stole a piece off the end of the loaf.

“Hell’s bells!” Lucky shouted and then to Daniel said, “Best be careful what you wish for. What if your only reward is to come back a dratted, thieving gull?”

“I’ve often wondered what it’d be like to fly.” Daniel sighed. “But I’m scared of heights.”

They trudged on until they passed into the shadow of the building.

“When we get to the spinning room, just follow my lead,” Daniel said as they joined the ranks of workers in line outside the door.

Fortuna appeared, grabbing Lucky by the shirt and pulling him off to the side. “Remember what I said about keeping your mouth shut,” he warned. “And stay away from that colored boy.”

“Why?”

“He’s not one of us.”

“He’s not much darker than we are.”

“He’s not at all the same as us,” Fortuna hissed. “We’re Cape Verdean, he’s colored.” An ugly sneer raised the side of his mouth, and Lucky noticed that his teeth were almost as square as the factory windows.

“Hallo,” someone called behind them. “Fernando, is that you?”

They turned to see Alice. Lucky looked to Fortuna, and as he watched, the ugly expression on his guardian’s face transformed to pleasure, then longing, and finally steely determination. Fortuna slicked his hair back, harpooned Lucky with a don’t-cross-me look, and strode over to where Alice waited.

Lucky hesitated for a moment, then turned to see the lady with the black shawl glaring at him.

“Morning, ma’am.”

“I’m surprised to see you,” she said. “Your type usually doesn’t last a day.”

“My type?”

She nodded. “Careless.”

Lucky opened his mouth to make a comment about the nosy, complaining, sourpuss old-lady type but caught himself just in time. Instead, he smiled widely. “And miss seeing your smiling face? No, ma’am, not a chance!”

She looked away.

“Your brother is sweet on Miss Alice,” Daniel observed.

“Only person that scoundrel cares about is himself,” Lucky said.

“That may be, but I have a feeling all his scheming has something to do with her.”

“What would she want with him?”

“Might be she wants him for a husband.”

“What’s he got to offer other than a bad temper and a greedy nature?”

“He’s a man of some means,” Daniel said as they stepped through the door, “especially now that he’s collecting two wages.”

In a dark mood, Lucky followed Daniel up the stairs to Spinning Room Three.

All that day, he watched and did as Daniel suggested. As loud as it was in the spinning room, Lucky was sure no one was able to pay much attention to anything other than the constant rotation of the big wheel, the rhythmic click, click, click of the cylinders as they were filled with thread and replaced while the wheel still spun, marking the minutes and hours. But Fortuna’s eyes followed him everywhere.

Lucky watched Daniel at work. His hands flew up to the cylinders, repairing the broken ends of thread before Lucky could even see they were broken. Sweat glistened on Daniel’s brow. He wiped it with a forearm and kept moving up and down the lines, putting up the ends of thread and repairing snags. Doffers, whose job was to replace spinning frames with thread, also occupied the floor, crossing the spinners as they worked their way around the machines as though weaving a net of fine threads.

Lucky moved down the row, sweeping fluff and ends of thread out of the way of the spinners and doffers. It was impossible to keep up. His head swam with the effort, and he paused for a moment, leaning against his broom.

Just then a shout rang out, loud enough to be heard over the machines. And then a scream, even louder. Anxious looks passed among the spinners and soon the huge wheel squeaked to a stop.

The spinners remained at their stools, except for Antone, who rose at a nod from Fortuna and passed quickly through the sliding door toward the cry.

In a moment Antone reappeared, nodded to Fortuna, and spoke to the spinner nearest the door. Word spread down the line until it finally reached Lucky: a worker in Room Two had gotten an arm caught in the loom. By the time the machine could be shut down, her bones had already been crushed.

“Better take care, little nipper,” Antone teased, “or you could look just like your landlady.” He pulled his arm into the body of his shirt, leaving the sleeve dangling. Parading across the floor, he swung the sleeve into the faces of the spinners. “Then Fortuna’d have a heap of trouble; what good is a one-armed sweeper?”

Little more was said amongst them, and soon the call came to make ready. Lucky worked his broom over to Daniel’s machine, so that when the mill wheel resumed, he could watch.

“Does it happen often?” he whispered.

“About every two or three weeks,” Daniel replied. “Briscoe tries to keep it quiet. Doesn’t want the reformers reporting on conditions.”

With a grinding whirr, the mill came back to life and again the spinners bent over their machines. Daniel pointed to the cylinders that needed threads put up. Lucky felt suddenly wary of getting too close. His right arm had begun to ache, and the furious twirling of the mules looked even more menacing. But after a while, he began to spot the barely perceptible thinning that would lead to a break. His friend’s hands moved in a blur over the reels, down the rows, here and there adjusting a machine, repairing a snag. Lucky could see why the other mulespinners were jealous. Daniel did it all seemingly without effort, his feet never leaving the ground.

One could probably work a lifetime and not be as good. Lucky supposed it was a bit like being a master rigger. You either had it in you to work the heights and the tight puzzle of ropes and knots, or you didn’t.

The heat and thick air of the mill bothered Lucky the most. He’d slept in many a stuffy and smoky fo’c’sle, but aboard ship one could always escape to the cool, fresh air of the deck. When they sailed into southern waters and the nights became hot, the crew often slept under the stars. Here in the mill, there was no escape from the heat. The air was so filled with lint it was hard to breathe, and many of the spinners and doffers who had been there as long as Antone coughed and wheezed their way through the shift. Lucky lifted Pa’s kerchief over his nose and mouth.

Just two weeks, he thought as the hours crept past. A body could put up with anything for two weeks, he reminded himself as he slipped for the third time on the oily floor. And wasn’t he more hardy than a dozen of these landlubbers? He looked around the room. They might work long hours, but whalemen worked around the clock, sometimes days at a time, with only a few hours’ sleep. Why, they’d worked so hard last year when the Nightbird had run into a pod of greasy luck, he’d forgotten his own birthday.

Lucky sucked in a ragged breath. He reached up to loosen Pa’s kerchief, hand shaking as his fingers fumbled with the damp cloth.

“Are you ill?” Alice stood beside him.

“What day is it?” he asked.

“Wednesday.”

“The date, I mean.”

She hesitated for a moment. “It’s the third. What’s the matter, Lucky?”

He’d done it again. He’d forgotten his birthday. As of yesterday, he was fourteen years old.

He opened his mouth to tell Alice, but stopped. Something about the concerned look on her face pulled at him, making his throat ache. He breathed in the oily smell of the spinning machines. “Just need some air,” he said, and walked toward the stairwell. As the door closed with a hard clank behind him, Lucky grasped the railing.

But even with his eyes shut, he couldn’t escape the presence of the mill around him. The vibration of its machines carried through the floors, up the rail, and into his fingers and bones.

“Are you sure you’re all right?” Alice had followed him out onto the landing.

Lucky blinked hard. “Better not let Fortuna catch you here.”

“Why? Fernando has no say over what I do. Besides, I think he’d want me to check on you.”

How could he explain? He must warn Alice, for she clearly had the little end of the horn where Fortuna was concerned. He cleared his throat. “A caution about Fernando, ma’am.”

She stepped back, looking puzzled, then held up a hand. “I know what you mean to say. He’s gruff—hard even, I know. But surely not beyond hope.”

Lucky eyed her skeptically. Was she truly addle-brained, or just having a go? But her hazel eyes were wide and her freckled brow wrinkled with concern. He felt strangely lonely now.

“I have a brother, back at home, just about your age,” she said. “You remind me of him.”

Lucky stood straight. “How old?”

“Fourteen.”

He relaxed. “I’m glad it wasn’t you got hurt earlier,” he said.

Alice sighed deeply. “I know her. The one who got caught. Fine worker and a good girl.”

“What happened?”

“Turned her attention away—just for a split second.” She shook her head slowly. They stood in silence, and Lucky wondered what the future would bring for the injured woman.

“You’ve got to pay attention every moment,” Alice said softly, “lest you end up with a life not of your choosing.”

Lucky’s cheeks burned. He thought back to the moment when he was snatched off the street by Fortuna. Was he here now because he’d failed to pay attention? Is that what she thought? He took a deep breath and tried to speak in a normal tone. “Are you saying you chose to work at the mill?”

She beamed at him. “I did. And my wages support my mother and the six little ones still at home.”

Her words were more than he could take. The control he’d worked to gain sailed out the window and it was all he could do to keep his voice steady. “Well I didn’t choose! Your sweetheart Fortuna chose for me! My wages go toward securing your future!”

Alice stepped back from the rail. She opened her mouth, then shut it, backing away from him like he had a pox.

She looked so hurt and bewildered that the anger drained from his temples down into his gut, where it sat like a lump of salt horse. She turned away, as if to collect herself before leaving the stairwell. He thought about what she’d said about Fortuna not being beyond hope. Unbidden, the memory of his last birthday came back to him.

Lucky had expected Pa to get him his first rigger’s knife as a gift. But when the Nightbird docked in Vera Cruz, Pa’d gone out on one of his benders, arriving back on board with only moments to spare before they’d sailed. Lucky’d made the mistake of asking whether he’d bought anything in port.

The pale skin under Pa’s stubbly cheeks and the smell of rum on his breath should have been answer enough. “Don’t pester me when there’s work to do,” he’d said, and swatted at Lucky like he was no more than a troublesome fly.

Later, when Pa was himself again, he’d bribed the cook with a bit of tobacco and gotten an extra ration of plum duff which he presented to Lucky the day after his birthday.

“Son,” he’d said. “I’m trying to do right by you. I believe there’s hope for me yet.”

Lucky let out a sigh. He’d gotten a rigger’s knife not six months later. Inherited when Pa’d died.

“What’s going on here?” The spinning room door swung open, and Briscoe stood before them.

“The boy felt ill, sir.” Alice stepped up to meet Briscoe.

“Indeed!” Briscoe pushed the door open and shouted against the frantic spinning and clanking of the machines, “Fortuna!”

He turned back to them. “You better get back to your loom, missy. That is, if you plan to collect any wages.”

“Yes, sir.” Alice stood tall. “I’ll walk him back—”

“The boy stays here!” Briscoe barked. “Get back to work while you still have a job!”

Alice nodded curtly at Briscoe, shot Lucky a look that he couldn’t read, and passed through the door. In the clouded din beyond, Lucky could make out the eyes of the other workers on them.

“You’re a lazy layabout,” Briscoe snarled, “and the sorriest excuse for a mulespinner’s assistant I’ve ever had the bad luck to come upon.”

For the second time in the hour, Lucky cheeks burned. He’d like to see this no-account fat-cat landlubber go up against a whale. Probably scare the stuffing right out of him. How dare he say that Lucky was lazy!

Before he had a chance to reply, Fortuna was through the door, bobbing and nodding like a fool, trying to kiss up to that son of a sea cook.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Briscoe. It won’t happen again. You have my word!”

“Your word doesn’t seem to mean much these days. Try to do a charitable deed and look what misery comes of it! I ought to toss both of you out the door!”

Fortuna bowed his head, but Lucky could sense his anger. It rose off him like heat rose off the spinning jennies.

“As it happens, I’m down a worker. So I’m going to give you and this sorry baggage you’ve brought with you one more chance.”

“Thank you, sir,” Fortuna said. He grabbed Lucky by the ear and pulled him through the spinning room door.

“What’d you say to Alice? Antone said she looked upset.”

“Nothing.” Lucky’s thoughts raced. What would Fortuna do when he found out what Lucky had said about him? He groaned aloud, glad for once to have his voice drowned out by the machines.