Greater Manchester, Cottonopolis, was once the world’s most futuristic city. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, architectural visitors like Karl Friedrich Schinkel saw in the repetition, inhuman scale and industrial materials of its mills a prophecy of the architecture of the future. We now live in that future. The unplanned industrial convulsions in China’s Pearl River Delta have their antecedents here. Nonetheless, Manchester offers a rather different aesthetic to the architectural traveller than that of toil and material production. More than any other city in Britain, Manchester has become a flagship for urban regeneration and immaterial capitalism. What other cities have dabbled in with piecemeal ineptitude, Manchester has implemented with total efficiency. If the regeneration that has taken place since the mid 1990s has a success story, it is surely here; and if we are to judge regeneration in its purest, least botched form, we have to turn to Manchester, a city which has neatly repositioned itself as a cold, rain-soaked Barcelona. Sit by Tadao Ando’s stained concrete furnishings at Piccadilly Gardens, squint at the strolling and coffee sipping, and you could almost believe it.

An impressive thing about Manchester’s new buildings is just how popular they are. In the newsagents, you can buy postcards of the Beetham Tower, Urbis or the Lowry, all sure signs that they have entered popular affection in a way relatively few modern buildings have since the 1960s—so to knock Manchester’s pride in its architecture could easily seem churlish, and the finer buildings here genuinely are superior to their equivalents in Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield or Glasgow, albeit within rather limited parameters. The populism of the new Manc Modernism should not be a surprise. Manchester’s regeneration industry draws extensively on the city’s legacy of extraordinary popular art, an area in which it has been markedly unimpressive since the early nineties, when the regeneration game began, although this doesn’t seem to have put anyone off. Regenerated cities produce no more great pop music, great films or great art than they do industrial product, although they may produce notable art galleries or museums. What they do produce is property developers—most famously Urban Splash, which has spread its ‘creative’ approach from here to as far as Plymouth; signature architects, such as Ian Simpson, subsequently much in demand elsewhere; and regeneration experts such as the unelected council leader Howard Bernstein, who is now busy transforming Blackpool, where he already finds a city devoted to leisure rather than having to transform a city of production into one of consumption.

Manchester City Centre has been repopulated over the last two decades to an undeniably impressive extent, at least in statistical terms: in 1987 its population was 300; now it’s over 11,000. As someone who has only the vaguest memories of the pre-regeneration city, I couldn’t help but approach the transformed centre without the requisite awe. The recession has led to the indefinite shelving of major projects like the Albany and Piccadilly Towers, so the regenerated metropolis has essentially found its final form. We are dealing with an unintentionally finished product, the most complete attempt to redesign an entire city on the basis of an alliance between property development, the culture industry and ubiquitous retail. In the process, the post-punk generation, even (or especially) those who considered themselves ‘Situationists’, has proved to be every bit as potentially corruptible as the hippies it reviled. Much as an oppositional, independent pop music has become a new museum culture in today’s Manchester, the Situationist critique of postwar urbanism has curdled into an alibi for its gentrification.

The Hulme Arch, entrance to the New Manchester

Ancoats, History–Prosperity–Technology

I make no apologies for the Smiths quotation that names this chapter. In the ultra-gentrified context of twenty-first-century Manchester The Smiths, along with The Fall, seem to matter much more than the Factory Records lineage of sleek Modernism. Both Morrissey’s unforgiving wallowing in the grim, grotty horrors of Cottonopolis and a self-constructed world of guilt, furtive desire and miserablism, and Mark E. Smith’s chaotic encryptions and denunciations are in implicit conflict with the blank Pseudomodernism that Factory’s industrial aesthetic eventually produced. The continuities are direct. The late, great Tony Wilson unfortunately spent much of the last years of his life as a propagandist for what the billboards in Ancoats call ‘New Emerging Manchester’, with the added Huxleyesque legend ‘History–Prosperity–Technology’. However, maybe The Fall are not so disconnected from the post-IRA bomb metropolis. Among the many, many quangos who have administered the regenerated Cottonopolis is one with the acronym ‘NWRA’—the North-West Regional Association, a Lancastrian regeneration quango which may just be connected with Mark E. Smith’s declaration that the North Will Rise Again. There are no coincidences in New Manchester.

The Los Angeles-based property developer John Lydon recently opined that he’d seen what a failure socialism was, because he’d lived in a council flat. This squares with the idea that punk was a sort of counter-cultural equivalent to Thatcherism—a movement for individualism, cruelty and discipline, as against the woolly solidarity and collectivism of the postwar consensus. Council flats were always an emblem of punk, at least in its more socialist-realist variants. There was a sort of delayed cultural reaction to the cities of tower blocks and motorways built in the 1960s, to the point where their effect only really registered around ten years later, when a cultural movement defined itself as having come from those towers and walkways. It wasn’t always actually true, of course, but when it was—Mick Jones’s Mum’s flat overlooking the Westway, for instance—it led to a curious kind of bad faith, where on the one hand the dehumanizing effect of these places was lamented, but on the other, the vertiginous new landscape was fetishized and aestheticized.

Although post-punk was always a great deal more aesthetically sophisticated, not bound by nostalgia for the old streets, this bad faith features here, too. Post-punk is usually represented in terms of concrete and piss, grim towers and blasted wastelands. This is best exemplified in the poster to Anton Corbijn’s woeful Ian Curtis biopic Control, in which Sam Riley, fag dangling from mouth, looks wan and haunted below gigantic prefabricated tower blocks (which, as we’ve seen, were shot in Nottingham, not the gentrified-out-of-recognition Manchester—although there are certainly parts of Salford that could still do the trick). Decades ago, when asked by Jon Savage why Joy Division’s sound had such a sense of loss and gloom, Bernard Sumner reminisced about his Salford childhood, where ‘there was a huge sense of community where we lived … I guess what happened in the sixties was that someone at the Council decided that it wasn’t very healthy, and something had to go, and unfortunately it was my neighbourhood that went. We were moved over the river into a tower block. At the time I thought it was fantastic—now of course I realize it was a total disaster.’41 (My italics.) This is often quoted as if it were obvious—well, of course it was a disaster. This is the narrative about Modernist architecture that exists in numerous reminiscences and histories: we loved it at first, in the sixties; then we realized our mistake, knocked them down, and rebuilt simulations of the old streets instead.

Decades on from the victories of punk and Thatcherism, after thirty years in which the dominant form of mass housing has been the achingly traditionalist Barratt Home or perhaps an innerurban loft, rather than a concrete maisonette, this yearning for old certainties, cobbles and the aesthetics of Coronation Street has a rather different resonance. In so many cases the places punk and Thatcherism wanted to destroy were swept away, particularly over the last fifteen years, in favour of ‘urban regeneration’. Yet the effect on the regenerated cities has been, in musical terms, unimpressive to say the least. In the 2000s, the very few areas to have retained a distinctive musical presence—forgotten estates in east and south-east London, depressed Yorkshire cities like Bradford or Sheffield—are those which have largely escaped regeneration. Meanwhile, Manchester—capital of regeneration with its loft apartments, its towering yuppiedromes, its titanium-clad galleries—has produced virtually no innovative music since A Guy Called Gerald’s Black Secret Technology in 1995. Jungle, garage, grime: all largely bypassed Manchester, while ‘alternative’ music degenerated into the homilies of Badly Drawn Boy, into innumerable ‘landfill indie’ acts, with or without attendant macho Manc swagger. You could blame this on the Stone Roses, or on Oasis—or it could be blamed on the new city created by an enormous and now-pricked property bubble.

Tony Wilson was evidently pleased that the guru of the ‘Creative Class’, Richard Florida, had designated the Manchester of young media professionals and loft conversions as a ‘cultural capital’, irrespective of the conspicuous lack of worthwhile culture created in the regenerated city—save for Mancunian auto-hagiographies like The Alcohol Years, Control or the egregious 24-Hour Party People. At the end of the most recent and most intelligent of these, Grant Gee’s Joy Division documentary, Wilson reflected on how Manchester had gone from being the first industrial city in the early nineteenth century to what is today: Britain’s first successful post-industrial city. After the blight of the 1970s it is now a modern metropolis once again, this time based on media and property rather than something so unseemly as industrial production. The old entrepreneurs built the mills where workers toiled at twelve-hour shifts and died before they were forty; the new entrepreneurs sold the same mills to young urban professionals as industrial-aesthetic luxury housing.

Wilson squarely credited Joy Division and Factory Records with a leading role in this transformation, but he was by no means alone in doing so. Nick Johnson, one of the directors of Urban Splash, has given presentations in which he dates the beginnings of his company to the Sex Pistols’ gig at the Free Trade Hall. Justin O’Connor, academic and co-founder of Urbis, the exhibition centre on ‘the city’ built on the IRA bombsite, claims that Wilson

found Richard Florida’s book and thought it said all that needed to be said about cities and that Manchester should pay circa 20k to get him to speak … I tried (to convince him) what a complete charlatan Florida was and how a ‘cutting-edge’ ‘creative city’ should not be ninety-seventh in line to invite some tosser from Philadelphia. He completely rejected this and never really spoke to me again. The last time I saw him was in Liverpool at a RIBA do. He was saying that Liverpool was ‘fucked’, unlike Manchester—and the reason was that Manchester had an enlightened despot (in the figure of the unelected Howard Bernstein). Which more or less set a seal on the increasing moral and political bankruptcy of the post-rave urban growth coalition which had taken over Manchester post-1996. Simpson, Johnson, Bloxham—now all millionaires—all claimed to have the new political vision for the re-invented city. Despite the fact that Bloxham—a man of little culture and education—was given chair of the arts council and now VC of Manchester university, thus confirming the toadying of arts and education to the ‘creative entrepreneur’, it is Wilson who represents its saddest failures. He made little money from it all, and really believed in it. Now subject of a nauseating hagiography by the city council that kept him outside for years, until the last four or five, bringing him in when his critical faculties had been worn down by years of punditry. He used to say, of the post-rave coalition, ‘the lunatics have taken over the asylum’; pigs and farm was more apposite.42

The narrative of Sex Pistols–Factory–IRA Bomb–Ian Simpson–Urban Splash has no room for the postwar years, decades of decline which just happened to coincide with the most fertile and exciting popular culture ever produced in the city (was it accidental, perhaps?). When Manchester is profiled or reminisced over, it is most often through a narrative which leaps from the Victorian city of ‘Manchester liberalism’—a laissez-faire doctrine with distinct similarities to Thatcherism—to the city recreated and regenerated after the IRA bomb in 1996. The horrendous poverty of nineteenth-century Manchester and the gaping inequalities of today are entirely effaced. In between is a no man’s land.

Both approaches have an essentially nineteenth-century idea of the city as a place that should rise autonomously out of the activities of entrepreneurs and businessmen. The unplanned cities of the nineteenth century have long been a touchstone of a certain school of psychogeography—a term originally derived from the Situationist International. Under the influence of English writers Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd, it has come to refer to an archaeological, vaguely occult approach to the city, where that which already exists is walked through at random, the rich historical associations leading to recondite, occasionally critical chains of association and reflections on the nebulous spirit of certain areas. Although this school of psychogeography is fiercely antagonistic to the glassy, security-obsessed cities created by regeneration, they share a hostility to planning and to the planned cities of social democracy. Although they come from political antipodes, both can agree about the ghastliness of council estates and the deficient aesthetics of 1960s tower blocks. If a certain strain in punk continues in much psychogeographical writing, it is the element that laments the destruction of Victoriana—the punk and psychogeographical preservation societies, symbolized best by John Betjeman’s journey from the ‘Hates’ list on Bernie Rhodes, Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s 1975 ‘Loves/Hates’ T-shirt, to ‘Loves’ on the remake Rhodes put together in the 2000s.

Psychogeography, as defined by the Situationist International, originally meant something rather different. While it certainly had an interest in those areas untouched by renewal, regeneration or prettification, the SI in the 1950s dared to imagine a new urbanism, an entirely new approach to the city which wasn’t based on two up two downs or on spaced-out, rationalist tower blocks. To have an idea of what the Situationist City would have been like, you could read Ivan Chtcheglov’s ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism’, an elliptical prose-poem imagining a self-creating world of grottoes and Gothic spaces, which, through the declaration ‘You’ll never see the Hacienda. It doesn’t exist. The Hacienda must be built’ inadvertently found its way into the annals of Manchester history.43 Chtcheglov’s city divided into pleasure-driven quarters is not as unlike contemporary Mancunia as one might assume, and a travesty of it can perhaps be found in the Green Quarter, Salford Quays or New Islington. There isn’t, however, any trace of another Situationist proposal for a new urbanism, New Babylon.

This was a proposal for a genuinely new city, designed by the Dutch architect, painter and early Situationist Constant Nieuwenhuis. A ludic city dedicated to play, where ‘creativity’ becomes its own reward rather than a means for the accumulation of capital, New Babylon is a blueprint for a city that might exist in a future in which automation has eliminated the problem of work. Here, there are no Le Corbusier tower blocks, Constant’s ‘cemeteries of reinforced concrete, in which great masses of the population are condemned to die of boredom’. Nor will you find here any homilies on behalf of back to backs, red-brick mills or outside privies, nor on the glories of the entrepreneurial city. If punk obsessed over the realness of the streets, New Babylon doesn’t even have streets, in the old sense—it is a construction based entirely on multiple levels, walkways, skyways. It is a city in motion for a population in motion, ‘a nomadic town’ that functioned as a ‘dynamic labyrinth’ entirely through means of modern technology and construction. Models of New Babylon show tentacles of elevated bridges above the existing city, linking together megastructures that are sometimes the size of a whole town in ‘a continuous spatial construction, disengaged from the ground’. The most important part of it seemed to be this element of circulation, the walkways and bridges themselves, designed to create accidents and chance encounters. Fairly obviously, for all the Situationist pretensions of Manchester’s regenerators, neither the Hacienda nor New Babylon has been built there.

However, Manchester may have had a fragment of New Babylon within it without really noticing, in the form of its major example of the New Brutalism. The idea of the multi-level city, which Constant and the Situationists argued had the potential to create a new urban landscape based on chance and on play, was very much in the air in the 1950s, particularly through the international architectural group Team 10. Although as practising architects, none of Team 10 was ever likely to be accepted by the Situationists, there is evidence that they had some contacts with Dutch members of the group such as Constant. Team 10 was an oppositional grouping which set itself up in opposition to the mainstream of Modernist architecture and planning. The structures it championed, opposed to the serried ranks of tower blocks that mainstream Modernism was erecting en masse, were based on walkways and the elevation of the street above the ground, based on the urban theories of the British architects Alison and Peter Smithson. The nearest built equivalent to this in Britain, though no ‘pro-Situ’ or psychogeographer would dare admit it, is Sheffield’s Park Hill, a building whose Mancunian offshoot has a decidedly complex history.

After leaving his post as Sheffield’s City Architect, Lewis Womersley set up a private practice with another architect, Hugh Wilson. Together, the pair designed two enormous structures in Manchester at the turn of the 1970s. One of them, the Arndale Centre, which swallowed up a huge swathe of the inner city and sucked it into a private shopping centre under one roof, is the antithesis both of New Babylon—dedicated as it is to work and consumption—and of Womersley’s work at Park Hill. Montage and walkways are replaced by a lumpen, grounded space topped by a lone office block, while its multiple levels benefit the car rather than the pedestrian. The other structure designed by Wilson and Womersley was the comprehensive redevelopment of the inner-city district of Hulme. The most notorious part of this, the Hulme Crescents, were a shadow, a memory of Park Hill; a series of labyrinthine blocks accessed by street decks. The relative conservatism of the Crescents can be ascertained from their names—John Nash, Charles Barry and so on, all taken from architects of the Regency period, to whose work in Bath and London this was intended to be the modern equivalent—and their prefabricated concrete construction was markedly less solidly built than Park Hill. Nonetheless, in the context of Greater Manchester, where dozens of blocks from Pendleton to Collyhurst rose out of the Victorian slums, gigantic spaced-out tombstones that amply made Constant’s point about the boredom factor of postwar redevelopment, the Crescents provided a Modernist labyrinth, its street decks winding round and interconnecting four vast, semicircular blocks enclosing a no man’s land of indeterminate pedestrian space. Within a couple of years of its 1971 completion, it was vermin-ridden and leaky, as a result of costs cut during the construction.

Hulme Crescents and its surrounding areas were demolished in the early 1990s. Apparently yet another example of the failures of British Modernism, its demise was seen as being nearly as pivotal for Manchester’s regeneration as the Hacienda, the Commonwealth Games and the IRA bomb. ‘Now of course I realize it was a total disaster.’ There’s another story about what went on within the street-decks, a story which suggests that post-punk was not so conservative in its urbanism. There’s no doubt that the early incarnations of Brutalist Hulme fully support the concrete and piss version of punk history. A 1978 World in Action documentary set out its stall early on, by describing the deck-access, streets in the sky system of the estate, then stating baldly ‘it doesn’t work.’ The documentary depicts the new Hulme as a rabbit warren, Constant’s labyrinth turned into a hotbed of crime, fear and paranoia, a place whose tortuous planning makes the seemingly simple experience of getting a pram into your flat into an ordeal, a place where rates of crime and suicide are off the national scale. Yet at the exact point that this documentary was being shot, Hulme was becoming something else entirely. Manchester City Council, which had at that point a surplus of council housing, was implementing a policy of rehousing the families that found Hulme so unnerving on housing estates with gardens in Burnage or Wythenshawe, leaving many empty flats. The Russell Club, which was home to the Factory nightclub, opened in 1978 by the embryonic record label, was surrounded by the estate’s concrete walkways—and the club’s clientèle would follow suit.

Liz Naylor, fanzine editor and scriptwriter of the Joy Division soundtracked film No City Fun, remembers how after running away from home in 1978 at the age of sixteen she asked the council for a flat. First of all, she was housed in Collyhurst, then an area with a heavy National Front presence. She asked for a flat in Hulme instead, because it had already acquired ‘a population of alternatives’, as ‘by then the Manchester Evening News had been running stories for years about how awful it was’. Not only was the Factory based there, so were many of the bands, along with fanzines like City Fun and recording studios. One of the most famous images of Joy Division was taken from one of the bridges over the motorway that bisected the new Hulme. Photographer Kevin Cummins later recalled: ‘the heavy bombing (of World War Two) along with an ill-conceived 1960s regeneration programme, conspired to make Manchester redolent of an eastern European city. Revisiting my photographs, I see the bleakness of a city slowly dying. A single image taken from a bridge in Hulme of Princess Parkway, the major road into Manchester, features no cars.’44 Yet this image of a depopulated, Brutalist Manchester as a sort of English Eastern Europe resonated in a less clichéd manner with those who chose to live in Hulme—it was welcomed. Naylor remembers that the entire scene was obsessed with Berlin—‘we weren’t sure whether east or west Berlin’—a fixation that also dictated what they listened to: ‘Iggy Pop’s The Idiot and Bowie’s “Heroes” was the music’. This extended to the films they saw at the Aaben, the estate’s art house cinema, where Fassbinder or Nosferatu were eagerly consumed by the area’s overcoated youth.

There was an attendant style to go with the Germanophilia. In her far from boosterist history of the area, Various Times, Naylor writes that ‘during the early 1980s there was a “Hulme look” when the whole male population of Hulme seemed to be wearing the clothes of dead men and everyone looked as if they had stepped out of the 1930s with baggy suits and tie-less shirts.’ The early eighties scene in Hulme, which included Factory bands like A Certain Ratio or ‘SWP types’ like Big Flame and Tools You Can Trust, was perhaps a romanticization of these surroundings, of the stark, ‘eastern European’ aesthetic, the sense of a Modernist utopia decaying, gone crumbled and decadent. Naylor remembers it being very comfortable in this period, ‘not scary’, an arty scene rather than the macho Mancunia that has dominated since the late eighties. Although post-punk Hulme could be seen as a sort of slumming, the families long since decamped to more hospitable areas, Naylor argues that rather than being just a form of urban tourism, this Hulme ‘became almost an independent city, another town within a town with a shifting stream of young, single people with their own dress codes.’

Especially intriguing is that this scene constituted itself here, in this bastardized approximation of New Babylon, this space of walkways, streets in the sky and vertiginous pedestrian bridges, rather than amidst old terraces or in between serried tower blocks. Partly this is happenstance: the City Council were essentially giving away the empty flats left by the families who escaped. But it also has surely to do with the possibilities of the structure itself. All the things bemoaned in the World in Action documentary as deleterious to family life—the labyrinthine complexity of the blocks, the noise and sense of height and dynamism, the lack of a feeling of ‘ownership’ in the communal areas—were perfect for the purposes of a self-creating urbanism. In Martin Hannett’s minimal, atmospheric productions, you can hear the ambiguous spaces created by the blocks’ enclosures; in tracks like A Certain Ratio’s ‘Flight’ or Section 25’s ‘Friendly Fires’ you can hear the lightheadedness of attempting to live in crumbling edifices somewhere in the air.

This sense of space is one of the most salient things about Manchester’s post-punk, a dreaminess necessitated by low land values, where the very fact that the spaces were unused or even unusable led to a sense of possibility absent from the sewn-up, high-rent city of today. Naylor stresses that rent is the great unspoken factor behind culture, and in Hulme, she points out, ‘hardly anyone was even paying any rent, including the rent boys’. The very emptiness retrospectively claimed as the blight from which regeneration saved the city was instead the source from which it drew its power. ‘The centre of Manchester’, she says now, ‘was like a ghost town. From 1979 to ’81 I’d walk around it, and no-one was there. Now, if you go to the centre of Manchester at 10 a.m. there’ll be a line of people from Liverpool queuing for Primark.’

Although she warns me that her views might now be coloured by nostalgia, Naylor raises the possibility that Hulme ‘became functional for people in a way that hadn’t been anticipated by the planners’. Or rather, in a way that was anticipated by the people the planners had drawn their ideas from, like Constant or the Smithsons, but which they had long since forgotten.

Naylor remembers the overriding feeling of Hulme’s sense of itself as an enclave, embattled but cohesive: ‘There’s no future, but if we stay here we’ll be all right’. Nonetheless, starting from the mid eighties, the drugs shifted from speed to heroin, crime became more common, Tory election landslides led to despair, ‘people started being mugged for their Giro’, and many of those associated with the post-punk scene moved on. Yet the New Brutalist Hulme went on to become a (fairly crusty, by many accounts) centre for the rave scene in Manchester, with the Kitchen, a club made by knocking through three council flats, being the Hacienda’s hidden reverse. In the mid nineties, on the eve of the Crescents’ demolition as a ritual sacrifice to New Emerging Manchester, there was another television documentary made about the place, this time for The Late Show. Only just over a decade later, and we’re miles from the hand-wringing of the World in Action documentary, with no condemnations of the idiocies of planners from the inhabitants. Instead, the Crescents’ occupants fiercely defend the estates’ light, air and openness, the possibilities of the streets in the sky, and the richly creative community that had established itself there, even in a context where crime and deprivation was still rife. One comments that a friend’s daughter ‘only found out she lived in a slum when she heard it on the news’. Meanwhile, if the streets in the sky had come full circle, back to New Babylon, then this is entirely supported by the documentary, which features images of travellers’ caravans in the open space between the blocks, reminding us that the hypermodernist Situationist urbanism of New Babylon was originally inspired by gypsy camps.

Homes for Change, Hulme

When Brutalist Hulme was demolished, what was built in its stead was a mix of social and private housing, with styles ranging from Barratt rabbit hutches to ‘Homes for Change’, designed in 1999 by Mills Beaumont Leavey Channon—an interconnected series of small but undeniably deck-access blocks. To the planners’ surprise, when the more militant of the former Crescents residents, who had formed a co-operative, were consulted, they insisted on the much derided streets in the sky. This part of Hulme at least is still very striking, and one of the very few examples of Brutalism—in terms of planning, at least—built in the last twenty-five years. If approached from the ‘Joy Division bridge’ photographed by Kevin Cummins (there are now proposals to rename it in memory of Ian Curtis), you can see in one direction the skyscraping Beetham Tower and Wilkinson Eyre’s Hulme Arch, an ‘iconic’ gateway to the regenerated centre erected in 1997, and in another, a large patch of wasteland, with low concrete walls providing much potential interest for a future Brutalist episode of Time Team, some standard Blairite office architecture, and just in the distance, the jumbled yellow and grey outline of Homes for Change.

Some of the moves the architects made here, such as the mix of materials—yellow brick, dark brown wood and metallic detailing—seem to be straight from the regeneration pattern book, but there the similarity ends. First of all, the materials are used ‘as found’, in the brusque Brutalist manner. You can still read the labels on the bottom of some of the blocks cantilevered out over the entrances, and mortar bulges rudely out between the cheap bright yellow brickwork. The walkways, metal rather than concrete, protrude seemingly at random, though their angularity is actually designed to catch the light. Even the artificial grass hill in the middle seems like a more domestically scaled version of the Smithsons’s own streets in the sky complex, Robin Hood Gardens in East London. The austere elegance of Brutalism is missing, however, with the ad-hoc look, a way of factoring into the design the adaptations tenants had made to their flats in the old Crescents, often seeming slightly whimsical. Like New Babylon, there is still a mobile architecture attached, with several caravans parked around the complex (with ‘Roma Supreme’ emblazoned on one of them). This is still a politicized space, but in a milder way, albeit without having anything to do with the Blairism of the centre. The blocks include studios and a café, and there is a van offering organic coffee in the middle of the courtyard. Homes for Change is by some measure the most interesting housing scheme in contemporary Manchester, especially in the context of the drab traditionalism that makes up the overwhelming majority of the new Hulme, but it might be caught—like much green politics—between an inspiring everyday utopianism and the politics of lifestyle.

Detailing at Homes for Change

Although the redevelopment of Hulme is often cited as one of the regenerated city’s successes, housing co-operatives with streets in the sky did not become the basis for the new Manchester. The place is based on an uneasy compromise, as the Homes for Change co-op were impelled to go into partnership with a Housing Association, in this case the Guinness Trust, and there have been periodic conflicts between the two over who actually owns the building. And where Wilson and Womersley’s Hulme applied avant-garde ideas on a massive scale, Homes for Change is of necessity a small and perhaps somewhat embattled enclave. Contemporary Hulme is itself another enclave (less gentrified than most) of a city which has dedicated itself to the service industry and the property market, bolstered by the propagation of an ideology of culture and creativity, where it matters little what the actual cultural product is, as the glories of the past can be lived off seemingly indefinitely. Hulme Crescents was one of the places where Modernist Manchester music was truly incubated and created, and its absence coincides almost perfectly with the absence of truly Modernist Mancunian pop culture. Yet what happened here—the use of spaces intended for working-class families by musicians, artists and so forth—is a strange inverse of what has been happening in the centre of Manchester since, a gift returned and in the process transformed into its antithesis.

For a picture of the New Mancunian metropolis, we start in Spinningfields, towards the river Irwell and the border with Salford. Recently zoned as the Business Quarter, it includes within it the People’s History Museum, as if to quarantine the city’s radical past on site. The new building for the Museum is clad in a rusty red corten steel, in some sort of ineffectual gesture against the opaque glass all around. There is in Spinningfields an alignment of Capital, in the form of buildings for barely solvent banks designed by Norman Foster’s B-Team; Discipline, in the form of Denton Corker Marshall’s Civil Justice Centre; and Property, in the form of Aedas’s Leftbank Apartments. These last are typical of Manchester’s many ‘stunning developments’, and a skyway adds a mildly futurist dash to the usual bet-hedging multiple materials and muddled geometries. Festooned with property adverts (a ubiquitous feature of contemporary Manchester), Leftbank is, according to the local property rag Manchester Living, ‘the home of credit crunch chic’—which is rather remarkable, given that only a year before these would have been marketed as ‘luxury apartments’ or ‘living solutions’. When we visit they’re festooned with an ad of a leering executive couple asking ‘Like what you see?’

Street sign, Spinningfields

The Civil Justice Centre and People’s History Museum

In a ‘marketing suite’ in Salford we picked up a selection of free property magazines, which proliferate here as if they were a substitute for a real local press, something which just about survives in the form of the trenchant non-believers at the Salford Star, a rare voice of sanity in New Mancunia. Amongst the magazines is one called Urban Life, and the copy we peruse features a column by a local radio DJ, decrying the sixties redevelopment of Salford as soulless high-rises, next to hundreds of adverts for new soulless high-rises. Irony does not sit well here. There’s more proof of this assertion round the corner, near the cute pop Modernism of the Granada building, in the form of Aedas’s Manchester Bauhaus, a mixed-use office and apartment complex. Walter Gropius’s estate must be irked that it never copyrighted the name—the new Bauhaus even replicates Herbert Bayer’s original typography. But in case we feel inclined to chart a simple, unbroken lineage of serene Modernism, it’s instructive to compare slogans. The Bauhaus, Dessau, in 1926: ‘Art and technology, a new unity’; The Bauhaus, Manchester, in 2009: ‘Business and life in perfect harmony.’

Leftbank Apartments, home of credit crunch chic

In comparison, The Civil Justice Centre is refreshing in its sheer aesthetic fearlessness. It is a genuinely striking building, although one eventually as unnerving as everything else here: the irregular protrusions at each end and the vast sheer glass wall are sublime in scale, suggesting a decidedly New Labour combination of domination and mock-transparency. Peering in, we see the ground floor houses ‘Café Neo’, a shimmering, cold non-space. You can’t possibly imagine something so grubby as one of the city’s many acts of petty crime being processed here. Nearby, on Deansgate, are two of Ian Simpson’s glazed apartment blocks. Simpson’s work is undeniably superior to the run of the regeneration mill, if only by default. His first major buildings—Number 1 Deansgate, the Urbis exhibition centre—both employ a sloping form that has been repeated by a series of lesser works in Manchester and Salford: Assael’s grandiosely named Great Northern Tower, BDP’s Abito Apartments, Broadway Malyan’s ‘The Edge’, all follow Simpson’s formula of sexy name, contrived irregularity and machined sleekness with rather less success, and all appear to be half-empty.

Café Neo, Civil Justice Centre

Urbis

Urbis is a curious gallery, its glass made opaque to protect the exhibits. It’s a flashy, dizzy memory of Patrick Geddes’s idea for an urban exhibition centre in an observation tower. Justin O’Connor, partly responsible for the idea, comments on its swift dumbing-down:

it was my idea and picked up in the absence of any other. However, the process of choosing the name, the architect and the building were done with no input from me at all. It was about two years into the project; after Ian Simpson had unloaded his preprepared designs with no reference to content (glass building for an interactive museum etc) and a management team cobbled together; only then did a stray question at a council meeting (‘what was going to go into this building’) lead the cultural supremo of Manchester to track down the author of the original eight-page memo (me, with some input from Tony Wilson) and ask us to tell him what it was all about.45

In typical pseudomodernist fashion, form preceded function by several leagues. O’Connor continues: ‘In effect all they had been concerned about was the building as icon. Ian Simpson exemplified the no-politics, no-intellect “intellectual”—able to strut with black polo-necked arrogance through his building refusing any signage (like, entrance and exit) in the name of aesthetic purity, even when rain was coming in from the roof.’ The first time we visit, Urbis features an exhibition on video games, some photos of ‘hidden Manchester’, drab recent New York art, and a small exhibit on the city’s (somewhat beleaguered) greasy spoon cafeterias—all with little context or information. As if as a final judgement on the ideas-above-its-station nature of a museum dedicated to a concept so abstract and arty as The City, by the end of 2009 Urbis was emptying itself of its original purpose, to become the National Football Museum. It’s difficult to imagine any fate more depressing.

Ian Simpson can’t be held responsible for any of this, of course, though he can be for the way his Beetham Tower dominates contemporary Manchester. In it, a mix of empty flats and footballers’ penthouses looks out over Cottonopolis, the Pennines and on a clear day, out to Liverpool. The Beetham Tower is distinguished by negative virtues, its lack of the aesthetic cowardice and confusion of most recent high-rises. It shows a mediocre architect at the very top of his game, and the relative virtues of the pugnacious local pride can be seen here, in that a native Manc has given the city something more distinctive and thought-out than megacorps like Aedas, Broadway Malyan or BDP would be able to offer. Moreover, Simpson’s towers in Birmingham and Liverpool are far, far worse, indicating that here the architect made a major effort—unsurprisingly, as he lives here. The Beetham Tower’s curtain wall is confidently unencumbered by the insufferable vernacular red terracotta and slatted wood, while its top-heavy massing creates a clear, distinctive silhouette without resorting to the silly hats worn by its contemporaries. Inside, the glass greenhouse effect is offset by lightness and opulent pseudominimalism. The Skybar’s cocktail menu offers a range of drinks named after songs by Manchester luminaries—the Buzzcocks, the Smiths, Happy Mondays (fancy a Hand in Glove?). Meanwhile, as if intent on re-enacting the plot of J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise, Simpson himself purchased the penthouse at the top for £3 million. He proceeded to fill it with an olive grove, revealed on a short BBC film about the tower. ‘It is aspirational’, he proclaimed. Post-punk Ballardianism is, then, reborn in the Beetham Tower in a most unexpected fashion.

Beetham Tower

The Beetham Tower Skybar (Great Northern Tower behind)

The most adroit user of Manchester’s pop culture fame in the service of property development is, of course, Urban Splash, which evidently shares Wilson’s opinion that the eventual point of Joy Division or Acid House was to lay the groundwork for post-industrial speculation and gentrification. After seeing how spectacularly it had fucked up Sheffield’s Park Hill, it was interesting to see some of Urban Splash’s successes. The redevelopment of Castlefield’s mills and warehouses are stylish and well executed enough—and if nobody is going to make stuff in them I suppose there are worse things than them being occupied by what Tom Bloxham once called ‘decision makers’.46 It’s marginally better than their being demolished, although the gated-off nature of much of Castlefield makes it less fun to walk around than it ought to be. Urban Splash has helped preserve what is, by any measure, one of the truly great industrial landscapes—the criss-crossing chaos of railway and canal bridges is utterly exhilarating, however marred it might be by some dull new-build flats. The true unpleasantness of the operation is, however, never far away. Along one stretch of Urban Splashed ex-industrial ‘lofts’ is a banner, advertising its never-begun (let alone completed) ‘Tutti Frutti’ selfdesign scheme in Ancoats. It declares: ‘COME AND HAVE A GO IF YOU THINK YOU’RE HARD ENOUGH.’

This ironic thuggery has another meaning in Ancoats itself, where regeneration has led to some extremely sharp disjunctions. The area between Manchester’s centre and this formerly pioneering (and famously impoverished) industrial district is already marked by the sleek modern architecture that is an arguable antecedent to the new city, an American modernism more about machined precision, minimalism and cold affluence than the earnestness and raw formalism of Brutalism. Here there’s the black glass of Owen Williams’s 1937 Daily Express printworks, and a set of excellent buildings designed for the Co-Operative movement, pioneered up the road in Rochdale, ranging from smart Dutchissue interwar brick Modernism to the glacial monolith of Gordon Tait’s CIS Tower, which vies with London’s Euston Tower and Sheffield’s Arts Tower as Britain’s most elegant tribute to Mies van der Rohe’s Teutonic America, and has the curious honour of being Tom Bloxham’s favourite building. You can’t imagine him citing the Co-Op’s main offices in Stockport, which take glass Modernism into bizarre kitsch, rejecting tower and podium for Giza-via-Trump pyramid. The CIS Tower’s architect dabbled in politics as a Tory councillor, and while its service shaft might now be clad in solar panels, stylistically this is emphatically not the Modernism of noble social programmes. It’s likely that this is what New Emerging Manchester wants to tap into, this lineage of sharp, businesslike Modernism. After crossing the road from the CIS Tower into Ancoats, a series of property billboards (white on black, in Helvetica) announce the area, trying to coax businesses into this proletarian district. ‘Ancoats is a Place to Pioneer’, it insists, accurately, although the many things that have been pioneered in its gargantuan factories are not wholly benign.

Manchester Modernism, Mk 1—The Daily Express

The Dutch Modernist CWS Building

Just north of here is Collyhurst, and a straggling landscape which demonstrates just how shallow the regeneration of Manchester actually is. Railway viaducts with every variety of shrub growing out of them lead to collapsing warehouses and ghostly council estates which somehow manage to feel peripheral despite being in the centre of Britain’s third largest city, but even they are less grim than the Green Quarter, a wall of massive new apartment blocks designed by locals Leach Rhodes Walker. A green space in the centre of this ‘Quarter’ provides a neat planning alibi for the relentless, domineering elevations, as profit is extracted from every other inch of the site. They’re a design nightmare, a headache-inducing clash of tiny windows, ‘friendly’ curves and unrelieved mass. In a sorry attempt to make them look less barrack-like, green render is slathered across the façades, as if at random. Meanwhile, one cluster of derelict Collyhurst council towers was sold (‘for £1 each’, says local rumour) to Urban Splash, who transformed them into The Three Towers. Clad in the obligatory wood (in this case almost hyperreal in its artificiality) and given the equally obligatory irregular windows, each block is topped by a beacon with the name of one of the Pankhurst sisters—Emmeline, Sylvia and Christabel, in flowing letters painted a hot lipstick pink. Some of the Suffragettes may not have minded this towering tribute, but Sylvia Pankhurst, founder of the British Communist Party, would no doubt have been disappointed if she’d known that a century hence, her name would be used to promote a transfer of assets from the poor to the affluent. It’s another example of the use of radical Mancunian history to sell Old Corruption all over again, the triad of land, property and finance given a lick of pink and lime green paint. It’s surely only a matter of time before some disused factory or council block becomes Peterloo Apartments or Engels Mansions.

The newly green CIS Tower

At its edges, visible from the main ring road, the new ‘Urban Villages’ of Ancoats look appropriately shiny and neat. Yet at the centre of it is an emptiness where the Cardroom Estate used to be. This was a low-rise council development of the 1970s that was demolished and re-branded by Urban Splash nearly a decade ago as ‘New Islington’ (what could be more ‘aspirational’?), one of a government-sponsored series of ‘Millennium Communities’. It is, to be frank, an awful bloody mess. Marked by huge swathes of wasteland and scattered industrial rubble, the area has as its centre a derelict pub, named—with perfect conjunctural timing—the Bank of England. There are two completed schemes, both funded by housing associations rather than the developers, both suggesting that Urban Splash’s eye for architecture contrasts with their fantastical ineptitude as urban administrators. Sober Modernists dMFK and unashamed postmodernists FAT (Fashion Architecture Taste) worked closely with residents to produce contradictory results—FAT’s display of cartoonish artifice, dMFK’s stern Brutalism—but both show a similar sensitivity towards their non-executive residents. Yet they’re set amidst dereliction and blight, loomed over by vast mills (renovated or rotting) and tower blocks in dire need of renovation, the area dressed at the corners with mostly dismal new architecture.

The wastes of New Islington

The farcical attempt on the part of Urban Splash and their state sponsors to build a ‘Millennium Community’ on the ruins of the Cardroom estate is a pop-PPP farrago which has levelled an area of social housing in one of those gentrification frontiers on the edge of Manchester’s ring-road. So far it has replaced it with one (apparently very hard to sell) Alsop block, two small closes of houses, and a whole lot of verbiage. The promised self-build enclaves, high streets, parks, schools and health centres weren’t built during the boom so sure as hell won’t be now, for all the Homes & Communities Agency money flowing in its direction. Irrespective of the awfulness of the place, FAT’s scheme is far more conscientious than seeming jollity might at first glance imply. In the blasted context of New Islington their houses look great, and only partly because almost everything else around them is so awful—while the use of a sort of trompe l’oeil wall/screen to pull together the terrace of clearly very modern houses is clever without being smug.

Bank of England, Ancoats

These houses present more actual ideas than all the other recent buildings in the city put together. Yet the low-rise nature of the scheme (something also used by the very different and similarly decent, if rather less intellectually interesting dMFK housing, also based on consultation with estate residents) makes it seem rather beleaguered, given the vastness of the mills and the yuppiedromes, and in the context of the wasteland all around the humour could seem merely grisly to the uninitiated; laughter in the dark. There’s also something deeply odd about creating a low-rise suburbia in the heart of such a huge city—but then people ask for some odd things. Sadly the furnishings left around the site—a cuddly little fibreglass bear, two fibreglass birds and a hedge trimmed to resemble a dinosaur, all sat near the broken millstones and fenced-off wastes—imply something infantilizing to the whole affair.

FAT’s houses at New Islington

dMFK’s houses, New Islington

This is more apparent in Urban Splash’s propaganda than FAT co-director Charles Holland’s own description of the place’s rationale (entirely coincidentally, he gave a talk about it the same day we visited). Holland explained in great detail the extent to which the estate was an attempt to meet the Cardroom tenants’ own desires—for houses with gardens and decoration—without patronizing them, instead treating them as thirty individual clients. Even then, his documentation of the alleged ‘wrongness’ of council tenants’ interior furnishings as a source of architectural inspiration had (no doubt unintentionally) a queasy Martin Parresque side, especially given that this ‘wrongness’ is purely in the eyes of the architecturally educated. There was one irresistible irony. After showing a set of photos from one Cardroom resident’s particularly eclectic 1970s interior furnishings, it turned out that when the FAT scheme was finished, this tenant filled his new house with Ikea-modernist new furniture. ‘Because I was moving into a modern house.’

Bear, New Islington

FAT’s work here is an ambiguous comment on the status of the ‘radical’ architect today—its houses are both within and against the overarching Urban Splash plan. The residents chose them precisely because they seemed most interested in their own ideas, rather than in slotting them into the slick towers and their attendant loft-living lifestyle. FAT’s designs were chosen precisely because they were the least Urban Splash-like of all that was on offer. At the same time, the images of these houses—with the wasteland all around invariably cropped from the shot, perhaps combined with renders of the never-built Tutti Frutti scheme—became the new fun and jolly face of real-estate speculation, of Urban Splash’s infantilist Innocent Smoothie approach to urban design. Master-planning and population transfer with an irreverent touch. But, as the many hostile reactions it has caused from right-thinking aesthetes can attest, it is genuinely different to the prevailing Pseudomodernism. When I first saw these houses in a Guardian article, my immediate reaction was horror—postmodernism returns in the guise of urban regeneration! Yet in the context of contemporary Manchester they seem far more subversive, a return of all that is repressed from regeneration architecture—most of all, the way in which taste and aesthetics are almost invariably determined by the unspoken matter of class. They represent a serious approach to designing social housing, contrasting with the deceptively simple drolleries of the decorative embellishments. It’s as if they decided to create a new aesthetic of public housing on the basis of the additions tenants made to their flats in the 1980s after they purchased them through Thatcher’s Right to Buy scheme. Architectural historian Steve Parnell claimed that FAT is the ‘only avant-garde architects in Britain’. If so, the avant-garde is in a strange place, where the only way to return to something resembling the original ideals of Modernism is to break every one of its formal rules. At the same time, to get their ideas built, FAT allowed them to become an emblem for one of the most spectacularly botched attempts at redevelopment in the Blairite era.

There’s no doubt that the non-Splashed areas of the redevelopment are worse, without even fragments of good ideas. At the entrance is Broadway Malyan’s Islington Wharf, which has a certain brash, supercity dynamism from its ‘good side’ (as Jonathan Meades pointed out in his regeneration diatribe On the Brandwagon, ‘iconic’ architecture always has a good side for photographs and another side blemished and pockmarked), but stodgy and lumpen from all the others. Curiously enough, its design appears to be a slicker remake of the Mathematics Tower at Manchester University, a Brutalist casualty to New Emerging Manchester, perhaps in some bizarre act of appeasement to the recent past. To the north, Jacobs Webber, formerly of the massive multinational corporate firm Skidmore Owings and Merrill, have produced the hilarious Skyline Apartments, a car-crash of ‘luxury’ new-build clichés. The proliferation of excrescences here happens all at once—the mess of materials, the inept patterning, the glass protrusion at the top, the nails-down-blackboard yellow—and is so awful that we were left incredulous. The website for the towers promises all manner of opulence, including a ‘Zen Room’. ‘Prepare to be seduced’, it begins, before suggesting you have your celebratory drinks the moment you get in (it’s furnished, you see!) and finally reminding you that it is aimed, of course, at ‘savvy city dwellers’ which presumably means buy-to-let landlords. To the south is Design Group 3’s Milliners Wharf, an imposingly long, featureless, loft-living version of an Aylesbury Estate slab-block. Will Alsop’s nearly completed Chips, the only other Urban Splash scheme after the housing association enclaves, appears in this context to be a more imaginative version of a generic Pseudomodernism. If dMFK or FAT had been allowed to design a whole area of social housing rather than tiny closes of ten or fifteen houses, this place could have been a genuine achievement, with or without its absurdly aspirational name, rather than what it is in the recession’s unforgiving light—a failed confidence trick.

Islington Wharf

Skyline Apartments

Milliners Wharf

Salford is the constituency of the disgraced Communities Minister Hazel Blears, who resigned due to her particularly impressive venality in the expenses scandal that formed a serendipitous distraction from the bank bailouts throughout 2009. One of the most authoritarian of Labour ministers (launching the nannying Five a Day nutrition campaign as under-secretary of health, defending various repressive measures as minister of state at the Home Office, and echoing the rhetoric of the British National Party as Communities and Local Government secretary), Blears is also one of the few prominent New Labour figures from a working-class background. Accordingly, her upbringing itself is mythologized as a subject of austerity nostalgia. She grew up amongst the deserving poor of Salford, and was featured as one of the child extras in a fine instance of austere Northern mythography, Tony Richardson’s film of that saddest of kitchen sink dramas, Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey. Her somewhat Thatcheresque rhetorical combination of 1950s schoolteacher and 2000s motivational manager led to a seemingly meteoric rise in New Labour, now perhaps only temporarily halted by a resignation elicited by the thrifty if not especially austere matter of huge, and possibly criminal, mortgage fiddling. A Times interview in December 2008 showed that Blears’s public persona was based on a curious combination of homely wartime rhetoric and utterly ruthless Blairite modernization, and as such is grimly intriguing as an exemplar of austerity nostalgia, only in her case lacking the requisite ironic distance. Much of the interview reads as a document from a country where World War Two never ended. Not only is Blears’s office decorated with the ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ poster, her rhetoric is pervaded by a strange combination of Victorianism and Blitz-spirit platitudes. You can see a frankly impressive performance of Blairite dialectic in her clear desire to play to every constituency at once. So she mocks bankers but laments (in a symptomatically progressivist metaphor) that the ‘train’ which the banks presumably commandeered didn’t transport every member of society; she defends the strict working-class Salford that created her and longs for the days when foremen would teach their workers ‘how to behave’, but also sticks up for the ending of ‘deference’ and backs off from the possibility that she’d ever stand in the way of anyone’s fun; and her obvious contempt for the Welfare State is combined with a belief that the working class need to be surveilled at all times. Perhaps the most interesting phrase used in the interview is that, in the recession, ‘we’ve all got to do our bit’.47

In her Times interview Blears with austere rectitude decries the 1980s as a time when yuppies caroused and others suffered, seemingly unaware that this is by now the public perception of the boom of the last decade (while the irony that it described her behaviour too, as we now know, is another matter). She represents one of the most unequal constituencies in the country,48 but one which has been very keen on remaking itself via a series of high-profile regeneration strategies on her watch. Most prominent among them is the transformation of the former Salford Docks into an exclusive entertainment and luxury housing enclave, soon to be occupied by a large section of the British Broadcasting Corporation. A less high-profile example is the selling of terraced houses condemned by the government’s Pathfinder Housing Market Renewal scheme (in which, as we saw in Sheffield, a property market was artificially stimulated in former manufacturing towns by the wholesale demolition of working-class housing) to the aforementioned Urban Splash, who turned them into ‘Chimney Pot Park’, a proletarian theme park for Manc media workers. Blears also talks of her love of modern buildings. What this means in the Salford context is Urban Splash’s austere/luxury enclaves, or the new jerry-built condos. She certainly wasn’t referring to any new housing for the Salford working class she perpetually invokes. Rather, she explicitly distanced herself from council housing in favour of the spectacularly severe solution of ‘mother and baby homes’. Blears’s make do and mend rhetoric was, as we now know, combined with mandarin corruption, a contradiction about which she appears oblivious.

Yet Blears is keen to exculpate herself and her government from the charge of neglecting the working class ‘core vote’ by referring to what they’ve done for Salford, so a trip over the Irwell is essential—and easy, as despite administering itself as a separate city, Salford is at the dead centre of Greater Manchester. You could cross via the swanky bridge designed by instant regenerator Santiago Calatrava, but to get the true measure of the place it’s best approached through the bleak dual carriageways, retail parks, office complexes and industrial estates of Trafford, where you get to see the bizarre Yeltsin-Constructivism of Old Trafford Stadium, redesigned by local architects Atherden Fuller in the late 1990s. This freakish mix of domineering symmetries and bared structure is heralded by a statue of Denis Law, George Best and Bobby Charlton, the United Trinity locked in embrace. Their faithfully rendered skinny bodies and skimpy 1960s kit contrasts vividly with today’s lumbering soccer supermen, leaving them looking dainty and rather camp, with a slight mince to their celebratory pose.

Public art at Exchange Quays, Trafford

The area near Salford Central station is full of mediocre 2000s high-rises, the districts near Salford University loomed over by their similarly drab, if less pretentious and more spacious 1960s forebears—but at least their straightforward geometries make their failings more easily ignorable than what has been built since 1996. At least they rehoused people in something better than what they replaced—and at least nobody kidded themselves these towers were part of some elite, exclusive Lifestyle. I spent a bit of time in the company of new-build chronicler Penny Anderson, whose blog Renter Girl profiled with wit and anger ‘Dovecot Towers’, the block in central Salford she called home, expanding into a wider critique of the shoddy tat marketed as the height of executive chic and revealing the hidden grimness of even the new middle-class enclaves. We visited Dovecot Towers, a chillingly bleak red-brick thing shoved into a Salford side street that she insists remains anonymous, but for a real negative-equity dystopia she recommended the ‘Green Quarter’ over the Irwell, a superdense mess of blocks dissolving into Cheetham Hill. We watched as a BNP van, complete with megaphone, sped past the CIS tower in that direction.

Salford has been hit especially hard by the demolitions of the Pathfinder programme, the second or third major wave of slum clearance the city has faced in the last half century, with many streets of terraces left tinned-up and derelict over the last decade. The earlier clearances led to the construction of thirty tower blocks, and a large concentration of these still survives in Pendleton, opposite the University of Salford. They are reached by a thin concrete bridge over a wide dual carriageway. Walking over it, the sublime terror induced by 1960s planning at its worst attacks you—the bridge can seemingly only let one person past at a time, and the fences are temptingly low. On each side are huge slabs, on one side running almost as far as the eye can see. Somehow here the planners managed to combine the sensations of agoraphobia in the form of the yawning ravine of the dual carriageway, claustrophobia in the form of the bridge’s mean proportions, and vertigo in the blocks’ twenty-five-plus storeys. Unnerving as they may be, they’re mostly now used as student accommodation. The two tallest are neighboured by a drive-thru McDonalds and a few derelict eighties vernacular brick cottages, these later accretions presumably being the reason why Control was not filmed here rather than in Nottingham.

Joy Division urbanism at Pendleton, Salford

These blocks are highly visible from Chimney Pot Park in nearby Langworthy, Urban Splash’s old Salford theme park, and they monolithically disrupt the fantasy of enclosure. Like in Sheffield, the developers’ remaking of former proletarian areas has been drastic, to say the least. The interiors have been completely stripped out, with steel frames put in their place, which provide first-floor patios at the back and black steel car parks where the back alleys would once have been. Everything is scrupulously regular, with burglar alarms, street signs and of course the titular steel chimneys all in the same sober, colour-coded language—Joy Division’s ‘Autosuggestion’ lingers over the obsessively ordered landscape: ‘here, here, everything is by design …’ Despite all the car parks, there are cars everywhere in these tiny streets, and cars provide a perfect hiding place for any undesirables who might want to enter the theme park. Given how poor the surrounding area is, they appear as an invitation. The cabbie who drops us off here (after we find it, spotting the tell-tale minimalist metal chimneys: unsurprisingly, he has no idea where Chimney Pot Park is) mutters ‘mind your pockets round here’ when we get out. There are plenty of places to hide and to escape in these close-knit streets, unlike in the gated blocks of flats in the city centre. Such are the drawbacks of Victorian urbanism, even when occupied by a better class of resident.

Chimney Pot Park

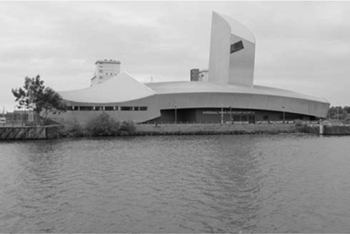

Imperial War Museum North

The Lowry, in its natural climate

Regardless of the straggling mess of much of the regenerated city, Salford Quays is where the icons are. Here is Britain’s most sustained push for the Bilbao effect, built on the site of the Manchester Ship Canal, a now useless but once technically astonishing feat of Victorian engineering that turned an inland city into a port. Aside from Michael Wilford’s messy but occasionally interesting Lowry, a building which, as if to prove Meades’s point, is from some angles clumsy and straggling, in others sharp and striking; and Libeskind’s minor but at least vaguely memorable Imperial War Museum, my main thought was ‘Wow, this is bad enough to be in Southampton’. The two icons are a strange pair indeed, linked by an arched bridge, the cladding of both the Lowry and War Museum nodding with amusing blatancy at Gehry’s Basque blob. The Imperial War Museum ‘symbolizes’ carnage through the imagery of a World Torn Asunder (it says so when you enter the building), but what Wilford’s building might have to do with the miserable marionettes of L. S. Lowry’s Salford is rather more mysterious. Libeskind’s and Wilford’s buildings might have made the magazines and brochures, but they are entirely dominated by DLA Architects’ woeful stone-clad high-rises, more luxury tat by Broadway Malyan and a nondescript slab for the now-defunct City Lofts, with more enclaves to follow. The BBC’s Media City is under construction, and while it’s nice to see it moving at least some of its functions from the over-favoured capital, it’s moving into a securitized enclave in marked contrast with the way the Granada offices insinuate themselves unassumingly into the heart of central Manchester.

Looking out through torrential rain over the Manchester Ship Canal at this, the most famous part of the most successfully regenerated ex-industrial metropolis, we can’t help but wonder: is this as good as it gets? Museums, cheap speculative housing, offices for financially dysfunctional banks? What of the idea that civic pride might mean a civic architecture for the residents of Greater Manchester’s crumbling tower blocks and condemned terraces? Cottonopolis might still be a vision of the future, but if so, it’s only marginally less unnerving than the nineteenth century’s industrial inferno. After the crash, we can see it as the ultimate failure of the very recent past, a mausoleum of Blairism. But what can be done with these ruins? The sheer stark strength of the remnants of the postwar settlement in the unforgiving light of the late 1970s inspired something equally bracing and powerful. How do you react to something which already tries incredibly hard not to offend the eye, or respond critically to an alienated landscape which bends over backwards not to alienate, with its jolly rhetoric, its ‘fun’ colour, its ‘organic’ materials? How do you find an atmosphere in something which tries everything to avoid creating a perceptible mood other than idiot optimism? It’s difficult at first to imagine what the ruins of New Labour could possibly inspire—but in places like the Green Quarter or Salford Quays you can almost hear the outline of it, the sound of enclosure, of barricading oneself into a hermetically sealed, impeccably furnished prison against an outside world seldom seen but assumed to be terrifying. We await the Joy Division of the dovecots with anticipation.