The Tyneside conurbation, or, as current branding calls it, NewcastleGateshead, is an area of wild contrasts. The first impression is of the serious urbanity of its nineteenth-century buildings. The Red-brick Gothic and Wrenaissance that denotes civic pride in so many English towns seems grasping and arriviste in comparison with the centre of Newcastle, which has far more in common with the more European urbanism of Glasgow or Edinburgh. Meanwhile, the multiple levels of the city, its bridges, walkways and steep changes of view give it a rare sense of spatial drama. Lots of this derives not just from the accidents of geology, but from planning: Richard Grainger’s planned speculative town centre is enormously impressive. There are two very good things about this area which are not shared by many English cities. The first is, as mentioned, the planned centre—odd to have something this good named after a property developer, or to imagine that all this dark classicism was part of a speculative development (and Grainger was apparently not a very efficient speculator, running up massive debts and risks). Regardless, the end result is that, like Glasgow, Newcastle looks like a city that actually had an Enlightenment as well as industrial capitalism, something that certainly can’t be said about Manchester or (pre-1953, post-1987) Sheffield.

Squaring this with the city I have read about in Viz for the last twenty years is difficult—at least until you see the remarkable women with their minuscule skirts, enormous heels and imperviousness to cold, with their somewhat less glamorous, shirt-and-chinos male charges, emerge for an evening’s entertainment at around 9 p.m. Nonetheless, even some awful malls and Terry Farrell’s egregiously bumptious ‘Centre for Life’ can’t spoil the centre of Newcastle, and the best postwar parts of it—the Civic Centre, MEA House and its walkways—seem to fit into it neatly. Even the accidents have a certain serendipity, as when the tower blocks and terraces seem to slot together into the same geometric pattern.

The Tyne Bridges

The other great thing is the Metro, and it’s amazing that it is this conurbation—smaller than the urban areas centred on Birmingham, Manchester or Leeds—that has this basic urban amenity denied from all other British cities save Glasgow, the capital and, partially, Liverpool. It has more than a passing resemblance to the U-Bahn, with spacious, tile-clad subterranean stations at the centre and outright weirdness further out where it consumes earlier rail lines, such as the alternately painted and picturesquely rusting ironwork of Tynemouth. Of late there has been talk of rebuilding some of the UK’s many closed rail lines, and we can only hope that if this occurs the Metro’s curious combination of antique and futuristic will serve as a model—and not only because it’s one of the few parts of our transport network still unprivatized (although that’s not for want of trying).

If it were only for this, and the succession of increasingly powerful, ever-more dizzyingly Constructivist bridges along the Tyne, culminating in the Tyne Bridge and the High Level Bridge, both of them more thrilling than any Thames crossing, the area would be worth visiting. There’s something insufferably patronizing about the idea that a city like this needed to be made more like Bilbao/Barcelona/London (or in an earlier era, Brasilia). Yet despite its remarkable urban qualities, Newcastle and its surrounding area has been ‘regenerated’ several times. A city this good ‘needs’ regeneration because its industries are long dead: dented in the thirties, wounded in the sixties and finished off by Thatcher. It had to run its economy on something—tourism and the wildly unstable property racket seemed the best bet. This is, let’s not forget, the home of Northern Rock.

While it’s appalling to treat Newcastle as if it were some sort of backwater before the arrival of lottery money, Gateshead is arguably another matter. Its nominal centre is still as shabby and aesthetically stunted as Newcastle’s is sweeping and sophisticated, a product of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries’ more budget aesthetics. It’s debatable whether its highly publicized riverside developments have had much effect on the town itself. Gateshead’s most famous buildings exemplify the area’s sharp contrasts. The first of these represents what most British cities are desperately trying to suppress: the memory of the first draft of an abortive northern renaissance in the 1960s.

Inside the High Level Bridge

The late Rodney Gordon, the most mercurial and pugilistic of the New Brutalists, designed two remarkable buildings in Gateshead with Owen Luder Partnership, both now facing demolition. One of them, Trinity Square Car Park, is best known on Tyneside (and everywhere else) as ‘the Get Carter car park’. It glowers out from its hilltop site, an abstract silhouette. Up close, it becomes one of the most visceral architectural experiences available in Britain, in terms of sheer physical power, architecture that both hits in the gut and sends shivers down the spine. Neglected for decades, it’s undeniable (and irrelevant) that the detailing is decidedly cheap, but its buckling, distorted strips of concrete remain overwhelming, storming heaven with a millennarian arrogance comparable with Newcastle’s outrageous, brilliant medieval Cathedral. It’s absurd that something so remarkable should be destroyed when, as we will see, several mediocre sixties buildings are being renovated, but part of it has already been. It is almost certain the car park will eventually go (although it still stands at the time of writing, in early 2010) and similarly certain that—as with its southern cousin, Portsmouth’s late, lamented Tricorn Centre—nothing of note will take its place. Nonetheless, the Tesco billboards emblazoned on the pink wall that surrounds the site try to convince us otherwise. ‘I love the new Trinity Square’, says one of its anonymous, regenerated ghost people, rather presumptuously.

A big man, in bad shape

To compare Trinity Square with other attempts to transform Gateshead reveals the jarring inconsistencies of the area. The 1986 Metro Centre, still the biggest mall in the EU, is far more dated than Trinity Square, to an almost cute extent—the themepark flights of fancy like ‘the Village’, a Disney Tyneside, are a far cry from the slick supermodernist Westfields. The Metro Centre’s unreconstructed pomo is almost charmingly dated—I went here at the age of ten, and even though I have no specific memories of it, on visiting in 2009 I felt I’d been here a thousand times. It is marked by a wonderfully contradictory tension between two models of non-place. On the one hand, the theme park approach most popular in the 1980s, with the central Village even featuring a Parish Chapel. The land on which the Metro Centre is built is owned by the church, strongly supporting The Pop Group’s claim on their 1979 single ‘We Are All Prostitutes’ that ‘department stores are our new Cathedrals’. This ridiculousness has seemingly absolutely nothing in common with the Metro Centre’s new bus station by Jefferson Sheard, a Northern firm that did some fantastic Brutalist work in sixties Sheffield.

The Village, Metro Centre

The bus station really did feel Cathedral-like in the sense of vast enclosure. However the Metro Centre itself, for all its hugeness, always feels poky and claustrophobic, always resists making the pedestrian aware of its scale. In that it’s like the ‘community architecture’ with which the nearby district of Byker is inexplicably lumped, refusing to do any of the things with space and scale that you can do with the form and instead basically creating a series of rooms where you can shop and eat (we had a Tex-Mex buffet, incidentally). It’s afraid of itself, of its own enormity. By comparison, the bus station is a Fosterian canopy seemingly designed for the personal edification of Marc Augé, where Elgar was being played loudly over the PA system, almost certainly as a means of dissuading youth from loitering there. The Metro Centre is not connected to the Metro transport system, and it’s telling that these two Metros, both built in the eighties, describe the consumerist tedium we’ve inflicted on ourselves, and a possible way out. The mall’s effect on the rest of Gateshead is vampiric, the direct cause of its town centre’s depopulated bleakness. Not that this area isn’t every bit as bleak, if not more so: looking out from the Metro Centre bus station, you see a post-industrial motorscape, bleak and straggling where central Newcastle is compact and exciting. No-one seems deterred by the post-industrial wastes they travel through to get to the Mall; it remains very successful, while the town centres in the conurbation (especially those outside the central Urban Renaissance zone) fall into dereliction. Undeterred, North Tyneside Council began in early 2010 to rectify this situation by designing fake shop fronts for the disused high streets of North Shields and Wallsend.

Metro Centre Cathedral

Descending into the Metro

The Metro Centre’s Thatcherite exurbanism contrasts in turn with the third New Gateshead, that quintessentially Urban Renaissance ensemble—the Baltic, the Sage, and the Millennium Bridge. This is easier to get to from Newcastle’s Quayside than from Gateshead itself. Foster’s Sage, though it looks beautiful from the High Level Bridge in the drizzle, opens itself out in a derisory manner to the car park, particularly unforgivable in the context of one of the few British cities with a reliable and extensive public transport system. The Baltic, undeniably aimed at tourists, is often accused of being over-scaled and irrelevant to the surrounding area, but the exhibitions and the public spaces are of a very high standard and I suspect that at least some arty young Geordies are pleased it exists. Still, whatever the merits of these buildings, they turn their back on Gateshead. The second time we visit, the poster draped over the riverside façade depicts a Miners’ Strike-era banner from the Martin Parr exhibition inside, declaring ‘Victory to the Miners, Victory to the Working Class’. Seen kindly, it’s an irruption of the repressed, but mostly it just seems a bad joke, a sign of powerlessness, that such an object can be displayed and no longer found threatening. The Baltic’s main knock-on effect is the Baltic Quays flats, arrogantly towering over the flour mills’ already domineering mass. Their ineptitude is almost matched by a cliff of poor executive housing on the other side of the Tyne.

The Sage, above the roofs

The remnants of an earlier attempt at regeneration sit at opposing ends of the Tyne, west of the majestic bridges. First, the tower blocks of Cruddas Park. These system-built (that is, assembled from prefabricated parts to a standard design from an engineer or builder rather than an architect) blocks exemplify the Newcastle of the corrupt, charismatic sixties city boss T. Dan Smith; not without a certain drama, better than the slums they replaced, but cheap and unimaginative compared with their contemporaries in Sheffield or their successors in Byker. Rumour has it that after his fall, Smith himself rented here. Yet Cruddas Park too must be regenerated, and the method is familiar: recladding (presumably losing the Mondrian patterns and abstract mosaics on the elevations); rebranding (as ‘Riverside Dene’); and soon, social cleansing, as council flats are flogged as luxury apartments for rent and sale. Over the river in Dunston, Gateshead, is a far superior example of sixties housing, at least visually—Luder’s Derwent Tower, or ‘Dunston Rocket’. This is unique, bespoke public housing and like Trinity Square, Rodney Gordon’s wild Constructivist-Gothic, all flying buttresses and distorted volumes, suggests Richard Rogers had he favoured shuttered concrete over neoprene. Like Trinity Square, it’s scheduled for demolition, yet the bulldozers have yet to arrive. There is a Save Dunston Rocket campaign, and perhaps some hope that recession will make the council reconsider demolishing yet another structure by this outrageously talented architect.

When we were looking for the tower’s entrance we were stopped by a middle-aged couple on their front patio, in the maisonettes which surround the tower. They asked if we wanted to take a picture of their front door, which we did. After all the time we’d spent wandering around estates taking photos, these were the first two people to express any curiosity about what we were up to, or seemingly even to have noticed us. They lived in the last part of the estate to be cleared, and were not best pleased about being forced to move from where they’d lived for twenty-six years. They spoke well of the flats’ space and how much they were liked after they were built. Nonetheless, they’d been told they would have priority for being moved to the ‘town houses’ that were being planned, which they expected to be like those on the riverfront. Given what we found in Sheffield, it’s doubtful whether a Labour council today can be trusted on such a commitment, but the alternative, if the residents are lucky and/or atypically affluent, is just round the corner. This is Staiths South Bank, luxury and individuality enclosed by a gasworks, lots of industrial sheds and the ornamental ex-industry of the Dunston Staiths, former structures for loading coal onto ships.

The Dunston Rocket, grounded

Designed by Ian Derby Partnership for Wimpey, with the much vaunted input of Red or Dead boss and ubiquitous design pundit Wayne Hemingway, Staiths South Bank is mooted as a revolutionizing of spec housing. While this stuff might be rare in Tyneside, Londoners or Mancunians will find it very familiar. It has some qualities, a diversity of façade and a (fenced-off) view of the strange and beautiful Staiths; yet is deeply mediocre compared with Rogers Stirk Harbour’s attempt to do the same thing in Milton Keynes. Perhaps the relative mediocrity is the point—the creation of a standard, deliberately nothing special. Yet the mannerisms imply individuality, even exclusivity. Its main claim to innovation, its attempted suppression of the private car, seems doomed in this desolate enclave served by neither Metro or train—and the public spaces are stuffed with cars. The area has a certain hint of dubiousness about it. Working Men’s Clubs with extremely expensive-looking cars parked outside. Of all the cities we’ve been to, Gateshead was the first where we got funny looks. Not hostility so much as ‘not seen you two in the Dun Cow’.

Staiths South Bank advertises itself

Dunston Staiths

Pedestrian Staiths South Bank

In its language of differing colours, mixed materials and contrasting scales, Staiths is (perhaps unknowingly) indebted to what might be, at least in superficial terms, the most influential housing project of the last thirty years—Ralph Erskine and Vernon Gracie’s 1969–81 Byker Redevelopment, a few miles to the east. Every block of yuppiedromes with painted balconies and coloured sloping roofs is a vague memory of Byker. Accepted history alleges this was the start of vernacular, community architecture, famously based on input from and co-operation with future tenants. Yet compared with other examples of community architecture, we are dealing with something very different. There’s no Poundburyesque wistful woolliness, none of the apologetic non-architecture of Militant’s council semis in Liverpool or the bland suburbanism of London’s Coin Street housing schemes (all the nondescript, apologetic eighties and nineties schemes which are usually used to define ‘community’ and ‘vernacular’, leading eventually in the US to New Urbanism, a school of thought which essentially rejects all urban planning and architecture after 1914). Byker’s salient features are wholly Modernist—walkways, towers, scale, sublimity, genuinely public space, stylistic consistency, and a programme to (re)house working-class tenants, not the ‘aspirational’ buyers courted by Staiths. It’s a product of the New Brutalist group Team 10’s other Modernism (Erskine was a member of the circle), as opposed to the reactionary fantasies of the New Urbanism—the mid-point between Park Hill and FAT, perhaps. Yet its Scando look, if not its ultra-modernist planning, has become as dominant as the attenuated Corbusier that Erskine’s team set itself against. It has faced social problems as much as anywhere else, and we suspect that if Anthony Kennedy, aka ‘Rat Boy’, the miscreant youth who transformed Byker’s manifold ducts and decks into escape chutes, had hailed from an estate clad in concrete rather than polychrome brick and painted wood, there would have been calls for the whole place to be dynamited.

Byker

Tower block at Byker

Nonetheless, this is a Modernist monument based on montage and consultation rather than master planning’s imperiousness, with odd leftover details from the slums it replaced forming the area’s only really postmodernist element. It retains a sweep, confidence, modernity and interest in sublime scale combined with small-scale intimacy that housing from the eighties onwards would completely abandon. It’s especially weird that it gets bracketed with the terminally dull housing-association architecture of the seventies and eighties—this couldn’t be further from the aesthetic cowardice of ‘vernacular’. And much as it would have been difficult by the seventies to see the utopian aspirations of postwar Social Democratic architecture, you have to explore Byker properly to see its originality. After all, its formal language was borrowed by all manner of hacks. But what is especially interesting about the area is the way the estate abuts what looks like the remnants of a canal, now landscaped into a pedestrian path towards the Tyne, inexplicably punctuated by a collection of tiny sheds (pigeon coops? Allotments?) which either borrowed the colours and styles used by Erskine or were borrowed by him. When you get out at the other end, you’re at the extraordinarily weird-mundane Ouseburn School, designed as a gesture to the Japanese businessmen who regularly visited this allegedly provincial city in the late nineteenth century.

The highly un-English Metro system takes you through an environment that can swing in minutes from density and drama to exurban desolation and back again. Tourist boards unsurprisingly favour Grainger’s town more than T. Dan Smith’s, yet the multilevel city created then still endures. Alongside one of these bracing plaza/walkway systems is the new library, an inoffensive glass block by Ryder Architects. This is the successor firm to Ryder and Yates, which itself grew out of Tecton, the Londonbased firm headed by Berthold Lubetkin through the 1930s and 1940s, responsible for Modernist ‘icons’ like the Highpoint flats in Highgate and the Penguin Pool at London Zoo. Yet unlike the famous post-Tecton southerners (Denys Lasdun, architect of the National Theatre, and Peter Moro, co-designer of the Royal Festival Hall) their work is relatively obscure. You can follow the walkways to their mirror-glass MEA building to see a trace of the ‘Brasilia of the North’ promised by Smith—or you could find it in Killingworth.

This, on the edges of the city, is a new ‘township’ planned in the 1960s. This really is a deeply strange place, where the remnants of a suburban Modernism coexist with the familiar limbo of spec homes and malls. These new spaces replaced a series of linked towers, the view of which in the distance is likened by the Pevsner guide to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, an office block on stilts and a Modernist shopping centre. Killingworth’s current, timelessly boring incarnation had to efface something more interesting first. In the middle of the ‘township’ is the obligatory artificial lake. On one side of it are some small, incredibly narrowly planned houses by Ralph Erskine, with paths that could get you lost even in this small space, and on the other side the faded sleekness of Ryder and Yates’s Norgas House. Round the corner is Ryder and Yates’s Engineering Building. Its hieratic International Style, in a remarkable state of preservation, is utterly alien among a desert of Barratt Homes and aimless roads. It’s across the road from a bus stop, so we could contemplate it for some time. The aggressive double-fencing around it was taking no chances whatsoever. It’s on these outskirts that you finally find traces of the New Economy, the concomitant of the tourism of the centre—the Quorum Business Park’s huge car parks and call centres, a hidden but mundane non-city, the would-be Milan or Brasilia replaced with Americanized exurbia. It’s a relief to get back in the Metro and what suddenly seems a comforting urbanity.

Today’s Killingworth

Killingworth Corbusier

We returned to Newcastle in late autumn, to see an exhibition entitled ‘City State—Towards the Brasilia of the North’. You can learn a lot about an exhibition from its comments book. In City State (helpfully subtitled ‘T. Dan Smith—What Went Wrong?’) the book has more arguments in it than most exhibitions have in their entirety. ‘A charismatic visionary’, scribbles one, ‘AN ARROGANT MAN!’ another; ‘demolish the lot!’ here, ‘saddening for a lost public vision’ there. Some are surprised that buildings they’ve always hated look so beautiful in John Davies’ photographs, others express admiration for Smith’s politics but note ‘what a mess he made of Newcastle’. It’s a reminder that no definitive judgements can be passed on Smith, save perhaps the six-year sentence passed down by the judge at his 1974 corruption trial.

Thomas Daniel Smith was of what people used to call the hard left. The son of a miner from Wallsend, after spells in the Independent Labour Party and the Revolutionary Communist Party (not to be confused with the eighties libertarian organization that continues as Spiked Online et al.), he took control of Newcastle Labour Party along with a group of fellow far-left entryists, and subsequently of the incongruously Tory Newcastle City Council in 1958, with the promise of massive rehousing programmes. Variously declaring an intention to make it a ‘Brasilia of the North’ or ‘Milan of the North’, Smith left Newcastle in 1965 to take a job heading the Northern Economic Planning Council, ran various PR companies, headed the Peterlee New Town Development Corporation, and founded a company called Open System Building, which would later be run by the architect John Poulson. In 1970, when Poulson went bankrupt, his accounts were meticulously pursued, landing Smith with a series of trials, some of which acquitted him, one of which sent him down for six years. By the 1990s he was living out his dotage on the fourteenth storey of a tower he had commissioned thirty years earlier, with enough gumption to play himself in a film, T Dan Smith—A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To Utopia. When thinking about Smith and Poulson, it’s impossible to keep from your mind their fictional portrayals on British television. Smith became Austin Donohue, corrupt local Labour leader in Our Friends in the North, a snake-oil salesman of ‘cities in the sky’; Poulson, meanwhile, was fictionalised as Red Riding’s John Dawson, portrayed by Sean Bean as a terrifying Yorkshire thug. This is the dark heart of postwar urban politics—backhanders, the threat of violence, one-time socialists forgetting they were in politics to help anyone but themselves, the tearing apart of once-great cities, the desecration of ‘heritage’. What is so interesting about City State is that it ignores this narrative completely, in favour of taking Smith’s urban ambitions seriously.

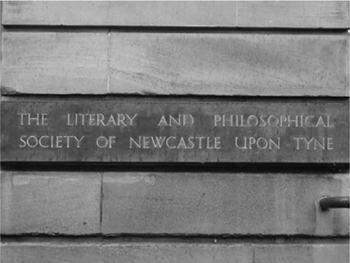

Newcastle’s urbanism is poised tensely between classical rectitude—the planned city designed by John Dobson and others from the 1820s to 1840s, which bankrupted its developer, Richard Grainger—and the exhilaratingly aggressive industrial structures that made the city its money. Both are implicitly combined in the Literary and Philosophical Society, an extensive library and debating society housed in a serene, sharp neoclassical building by John Green. It was headed at one point by Robert Stephenson, the engineer whose proto-Constructivist High Level Bridge sliced a castle in two, something which would give any heritage watchdog today a coronary. It is, then, an appropriate place for this ambiguous half-celebration of a council leader best known for his destruction of traditional Newcastle. The images in City State show how this destruction, the domineering nature of modernity and the way its structures leap over, crush or transcend tradition, is a part of what makes the place distinctive, and not at all its opposite. The organizers hired for this the great photographer John Davies, whose book The British Landscape offers twenty-five years of wide-angled monochrome photographs of Britain as it actually is. Along with images of Stockport viaducts and Durham pit villages, The British Landscape contains astounding photographs of usually derided, master-planned postwar landscapes—the chaos of intersections in Herbert Manzoni’s Birmingham, the meticulously planted hillscape of J. L. Womersley’s Sheffield—taken from the planner’s vantage point. That is, from above, seemingly either from the top of a tower block (where the perspective is supposedly bleak and isolating) or an office block (where it is the perspective of the lord of all he surveys). These images combine a certain classical stillness with a barely suppressed charge of excitement.

Their planner’s-eye view is wholly appropriate. Under Smith, Newcastle’s was the first English council to have a planning department (headed by one Wilfred Burns) and here you can see the brochures and PR booklets sent out to council tenants that detailed the benefits of urban motorways and point blocks. With inadvertent irony, one booklet notes that ‘much of the money needed for the five year plan will be borrowed’. Davies took a book’s worth of photographs of the area, and these decorate the walls of City State. Where contemporary critics like Ian Nairn saw an international style of boredom unworthy of Newcastle, he claims to have found something unique. In fact, he goes as far as to say that this is ‘unlike the architecture of any city I have photographed’, and sets out to prove ‘the distinctiveness of Tyneside Modernism’. What makes it distinctive, according to Davies’s captions, is the way the buildings support themselves on massive pillars, which allow pedestrian or vehicle traffic to pass underneath, or fire off pedestrian walkways, flyovers and overpasses from over and under. Other elements are apparent, such as a strange neo-medievalism in the design of office blocks and the Bank of England, the use of rough stone or concrete, a generalized northernness; all with a black and white palette imposed by the council. The photographs were taken in the last year or so, and they show the multilevel city in an ostensibly well-preserved state, the recent cladding and/or rotting masked by the monochrome. The finest of these buildings look breathtaking in these images. RMJM’s Swan House becomes a sublime elevated grid, at the centre of a riot of walkways and highways, while Ryder and Yates’s MEA House appears as the strange, angular terminus of that same system. Meanwhile, the council was every bit as ruthless about ploughing the private car through the city as their 1840s predecessors were about slicing it into pieces for the benefit of the railways. With hindsight we can see what a mistake that was, and, as we find out five minutes after leaving the exhibition, there are few places as uninviting to the pedestrian as the point where Swan House meets the Tyne Bridge. Yet this is more to do with a failure to achieve Smith and Burns’s aim of completely separating pedestrian and traffic than the evils of the aim itself.

The problem with the idea of the Brasilia of the North is that Newcastle never found a northern Oscar Niemeyer. This was not for want of trying. Smith invited Le Corbusier to design what would have been his only British building, although it never worked out. He did manage to convince the Danish architect Arne Jacobsen (designer of that other icon of 1960s corruption, the curved chair which Christine Keeler famously straddled) to redesign the neoclassical set piece of Eldon Square, although he was sacked after Smith left the council, meaning at the very least that the banal mall which sits there now can’t be blamed on him. As it is, Smith relied upon Scottish architects such as Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall (designers of the walkways and Swan House) and Basil Spence (designer of a cluster of blocks by the Tyne Bridge, and the now-demolished Central Library), along with locals Ryder and Yates. English artists were employed for the public art which accompanied the buildings, such as the Victor Pasmore murals in the Rates Hall of the new, Scando-style, no expenses spared Civic Centre (‘as they fingered their chequebooks or opened their purses, I longed for [ratepayers] to snarl “this is the end!” ’50).

It was decent enough, but where Smith’s administration really succeeded (and failed) was in the rehousing of his core constituency, the working-class voters of Newcastle. The high-rise estates take up fairly little of City State, perhaps because they don’t fit the thesis of civic ambition, although one image of a Shieldfield block raising itself up on pillars fits the overarching idea of a distinctive Tyneside multilevel metropolitanism, and the cubic houses by Ryder and Yates in Kenton look extremely weird. After Smith, the Byker slums that his administration had cleared were redeveloped by Ralph Erskine in the sort of sensitive Scandinavian Modernism Smith had tried and failed to impose on Eldon Square, but couched by a Tory council as an explicit alternative to Smith’s schemes like the Cruddas Park high-rises. Meanwhile, the most famous buildings of the time are in Gateshead, outside of Smith’s jurisdiction, in the form of Owen Luder and Rodney Gordon’s Trinity Car Park and Dunston Rocket.

The walkways to MEA House

Norgas House

All of this is photographed by Davies as part of an argument that the greater ambition of the time was to do with an intriguing fusion of regionalism—devolution, fierce local pride—and internationalism, achieved by looking out towards Europe and the Third World for ideas both architectural and political. So the architecture of the entire area makes up a wider picture of a potential enclave, a genuine city state, which Smith and his allies attempted to create through the Northern Economic Planning Council and New Town Development Corporations. This is where Harold Wilson’s Labour governments were at their most interesting, and most unlike those of Blair and Brown: where they made a serious attempt at a real reorganization of power in the United Kingdom. In the corner of the exhibition a three-hour film, Mouth of the Tyne,51 shows footage of Smith in the mid 1980s, explaining the ideas on devolution he lobbied for in the 1960s: Britain divided up into eleven locally administered areas, each of which would control the ‘commanding heights’ of its local economy. These would elect a representative to a second chamber, replacing the House of Lords. This would then be integrated into a federal Europe, and in the process the south-eastern aristocratic biases that skew British politics would be eliminated. The failure of this is all around us, as Old Etonians dominate the government and their think tanks advocate the population of Sunderland moving to London.

Some of Smith’s ideas sound really rather similar to the ‘Urban Renaissance’ announced by Lord Richard Rogers. The estate he commissioned overlooking the Tyne, Cruddas Park, is currently being reclad and rebranded as luxury duplex development Riverside Dene. In these eighties interviews, meanwhile, he talks about wanting to make Tyneside into a ‘science city’, removing its reliance on ‘yesterday’s industry’, i.e. coal and shipbuilding. There’s no truck with nostalgia for the local past but a clear intent to build something more high-tech on top of it, partly through a massive extension of polytechnic education. Then there’s his use of more civic-minded European cities as exemplars, his talk of ‘science parks’ rather than factories and, perhaps most importantly, his emphasis on culture. The ‘philosophical background’ of Labour’s plans for the area was Northern Arts, an organization he founded. The discussion of the importance of arts and, by implication, of tourism, sounds like an inadvertent prophecy of the Blairite urban renaissance and its local incarnation, the ensemble of Millennium Bridge, Sage and Baltic that is carved out of the post-industrial Gateshead Quayside. The accidental descendants of Smith’s New Town science parks are no doubt the call centre colonies of Killingworth. The difference, of course, is that Smith’s kind of regional boosterism had a place for democracy and for socialism, both of which are as absent from today’s NewcastleGateshead as they are from everywhere else.

John Prescott may or may not have had Smith in mind when he devised plans for regional devolution in the early 2000s. Perhaps because the Greater London Authority, the Welsh Assembly and the Scottish Parliament had managed to carve out niches to the left of New Labour, the North-East Assembly was designed to be a relatively toothless creature. Nonetheless, the region’s overwhelming rejection of the plan in a 2004 referendum perhaps shows that it doesn’t want to become a city state, an independent metropolitan area able to step out of London’s shadow. People in Teesside or Wearside would apparently rather be ruled from Thameside than Tyneside. As it is, rather than being able to reject the more unpleasant whims of New Labour, as have Scotland and Wales, the area is instead largely administered by a multitude of competing unelected Regional Development Corporations, who can pursue Pathfinder schemes more brutal than any 1960s slum clearance. Meanwhile, Newcastle became the epicentre of the financial earthquake when Northern Rock (based, incidentally, in the Regents Centre, an out-of-town office complex built under Smith) had to be nationalized to save it from collapse. The 2004 referendum and the Northern Rock collapse were a return as farce of the calling-in of accounts that did for Smith, much as the crash of Blairism was the sorry echo of the crash of social democracy in the 1970s, this time without any principles whose betrayal we could lament.

What of Socialism, presumably the reason Smith entered politics in the first place? Was he just on the make, or was the graft all a means to a definite political end? Naturally, Smith consistently claims the latter in Mouth of the Tyne. Yet the documents assembled at City State show a dizzying quantity of business ventures—in PR, engineering, design, painting and decorating—all established with the ex-Trotskyist’s adroitness at setting up front organizations. They sit strangely next to his notes for speeches at ILP or RCP meetings—‘workers of the world unite!’ is scrawled on one of them, something you just don’t get with New Labour civic dignitaries like (Sir) Bob Kerslake and (Sir) Howard Bernstein. The video footage shows Smith building up a complicated, often unconvincing but strident and intriguing defence of his, ahem, ‘extracurricular’ interests. He claims that the reason he established such close links with Poulson was because he was an opponent of system-building (note here the name of Poulson and Smith’s former business venture, Open Systems Building, and take the following with a heavy pinch of salt). In fact, he claims, rather than being the corrupted, he was using Poulson all along in order to influence architecture and planning on a nationwide scale, so as to shift it in a more careful and individualistic direction. ‘I wanted to influence as many British cities as I could, and Poulson was my instrument for that.’ The nondescript, interchangeable curtain-walled towers that Poulson produced for British Rail, some of which still survive, are proof of just how questionable Smith’s assertions here are. It sounds like a post-facto rationalization of entirely contingent alliances, yet put across with a certain gall: ‘if I had been successful and Poulson had been successful, then 70 per cent of the problems of our town centres would have been avoided’; apparently none of their blocks would have been system-built. ‘I have no moral qualms.’

This is as maybe, but one thing which is certain is that Smith pleaded guilty in 1974—although even this, he claims, was because of ill health brought about by a nerve-steadying diet of ‘Valium and Carlsberg Export’. Mouth of the Tyne ends with Smith discussing the power structure of money both old (the House of Lords, the public schools, Oxbridge) and new (financial and industrial capitalism). He claims, plausibly, that he was too powerful and too influential to be allowed to continue at the top, an area strictly reserved for those who have been groomed for it, where after Eton and Cambridge ‘the sign on the bus stop reads “to the power structure”.’ These ‘non-elected people that you never hear about’ were in his day sundry Lords and civil servants. In ours we could add the multiple Regeneration Commissions and Local Development Corporations, with their names like Yorkshire Forward, Creative Sheffield, Bridging Newcastle-Gateshead, One NorthEast, Housing Market Renewal Pathfinder, and knighted, unelected council leaders like Bernstein and Kerslake. This particular variant of quango was pioneered by the Wilson government, and many of them had T. Dan Smith on their board.

Damien Hirst and/or Victory to the Working Class

In this 1980s footage, a red-faced, tired but pin-sharp and funny Smith declares that ‘capitalism itself is fundamentally immoral and corrupt, and its major corruptions are all legal’. It’s both utterly true and a rather poor alibi. Yet listening to him, you can’t help but think how relevant his rhetoric is now. He notes that working-class movements are told by ermine-clad Lords that their politics are outdated; today, Baron Mandelson of Foy tells trade unions to move with the times. Smith claims the real corruptions are legal; while he got six years, Northern Rock chairman and enthusiastic neoliberal ideologue Matt Ridley escaped without even a fine. As the missing link between Marxism and Mandelsonism, T. Dan Smith appears here as the ultimate political curate’s egg: fascinating and charismatic, creator of an impressive but often despised landscape, both convincing and dissimulating, a corrupt mandarin who intended to create a decentralized socialist Britain. Swallow it all whole and it might poison you, but better a man who got his fingers burnt when trying to create cities in the sky than when claiming expenses for mock Tudor beams. Tyneside’s first version of an urban renaissance holds out the faint promise that a city could be transformed on its own terms.