What distinguishes Cambridge amongst the cities in this book is that it shouldn’t need any kind of regenerative interventions. Not only is it the seat of the most powerful and ‘best’ University in Europe, it’s the pulsating centre of the New Economy, and the research pivot around which the Silicon Fen of ‘new settlements’, business parks and science parks revolves. In Cambridge, we should find out what success looks like.

On apprehension of the area around Cambridge Station, success looks like a lower-rise version of Leeds, with all the paraphernalia of the ineptly regenerating northern industrial cities. There’s a towering derelict flourmill, wasteland, cheap ‘luxury flats’, a gigantic leisure complex with attendant multi-storey car park, and a paucity of real public space. In the North, there might at least be a certain scale and pride in such an ensemble, but here it looks even shoddier. As an introduction to the city which has perhaps more than any other pioneered the alleged replacement for the industrial economy, it’s unprepossessing to say the least. Architecturally, it gives a false picture of the city, but in its obstructive planning it harmonizes perfectly with the rest of contemporary Cambridge.

So it seems Cambridge has almost as many brownfield sites as anywhere else, but they are not always so ineptly used as they are in the area round the station. Within walking distance, on a former ad hoc government site, is Accordia or, as it calls itself, ‘Accordia-Living’, winner of the 2008 Stirling Prize. This is a very large housing estate developed by Countryside Properties, a volume house builder. The architecture here, by ‘Humane Modernists’ Fielden Clegg Bradley, Alison Brooks and Maccreanor Lavington, became a brief cause célèbre as the anti-icon; the clipped, nobullshit riposte to recent fashionable nonsense, its architecture made to be lived in rather than photographed. It is extremely high-spec as these things go. Although we’re under no delusion that the show homes are anything other than the largest and most well-appointed of the properties, the one we see is full of space, surprising internal arrangements and multiple balconies. It is surprising in the sense that one of the bedrooms has a little mezzanine overlooking it, for the voyeurs. The bed is picked out in purple and black. The opulent and kitsch interior decoration totally reverses the ethos of the severe but smart exterior, in that it looks expensive but also decidedly tacky—though it would be a perfect set for a future film about cynical, philandering academia, a sort of science-park update of Joseph Losey’s Accident. However, any sexual tension is dampened by the show home’s strategically placed children’s wellingtons.

The architecture of success

The bed is made at Accordia

Accordia’s style, meanwhile, is the most recent example of the contextual Modernism introduced by Leslie Martin in the 1950s when he transferred from the London County Council to Cambridge as architectural overseer—yellow brick, a very obvious Alvar Aalto influence, quadrangles and courts rather than houses and gardens. It’s totally devoid of amenities of any sort, but then nobody worries whether social atomization will ensue if a few hundred wealthy people are shoved together in an area without a grocery shop or a nursery school. There is a rhythm and strength to the buildings here which is extremely rare in speculative developments, but the language taken up from Leslie Martin rankles somewhat: this ‘post-war pretence of a proletarian humilitude’, as John Outram mockingly called it, hence his maniacally aristocratic riposte, the Judge Institute, of which more presently. Accordia, like its postwar forbears, is a modest council-house Brutalism for an area which is, if anything, upper class. There is (relatively) ‘affordable’ housing here, so diminutive it can be spotted a mile off, and unfinished flats whose cladding shines golden—finally owning up to how expensive the whole project actually is, a brief flash of unashamed bling before it weathers into the dun of the rest of Accordia. The essentially kitsch nature of the place is made clear in the property brochures, where each of the building types is given its own name—‘Accordia Dawn’, ‘Accordia Vista’, or for the more petite parts of the estate, ‘Accordia Light’. At one corner is the real utilitarianism of a 1960s fallout bunker, apparently converted to storage, though given Cambridge’s air of paranoia we suspect it was retained just in case. The affordable housing abuts it, and the roofs harmonize with the angles of the bunker in the most peculiar example of contextualism.

Accordia

Bling at Accordia

Accordia is for sale, so it encourages visitors. This in itself marks it off from the rest of Cambridge, which outside of the tiny centre is one of the most unwelcoming cities I’ve ever visited. Nonetheless, that centre is not without interest. Here you can find remnants of a quaint university town, the expected and frequently breathtaking tourist attractions (King’s College Chapel and so forth), and some pugnacious irruptions of modernity which are the result of either Baedeker Raids or the University’s ‘progressive’ reputation. This leads to some very surreal juxtapositions—Silicon Fen business parks slotted between Gothic churches and Span estates. In one passageway, you have in sequence J.T. Design Build’s Vegas-Palladian Crowne Plaza; the functionalist backside of Chapman Taylor’s desperately nondescript John Lewis store; and clambering over them all, Arup Associates’ 1971 Computer Laboratory, a lanky, fearful creature reminding the heritage city of the technocratic reason for its national prominence.

The tastefulness is broken up by Arup’s lab, but not as much as it is by the 1995 Judge Institute. Outram, easily the most original of British postmodernists, a one-time associate of Archigram who brought some of its garish extremism into this generally lumpen restoration style, was clearly unimpressed by the city. In a hilarious and slightly crazed attack on its humble modernism-lite, he wrote, accurately:

Bunker at Accordia

the Dons and Fellows disliked being exposed as being possessed of recherché cultural qualities; more especially as they had no secure means of judging whether this ‘difference’ was properly mediated by an Architectural Medium whose dominant, and spuriously ‘local’, qualities, since 1945, had been to deny itself capable of any rhetoric except that of the ‘honest, proletarian, woodworker and bricklayer’. This was the so-called ‘Cambridge Style’, as it was known from the 1960s onwards … more suited to the pedagogy of milking-cows than the most brilliant young minds of Britain.56

Indeed. We are unable to go into the Judge Institute, which I rather regret, and pause only at its puzzling, oblique gates, but it looks spectacularly bonkers in Outram’s own drawings and photographs: a garish, Piranesian, wilfully tasteless mock-aristocratic extremism in ‘blitzcrete’ that can clearly épater les bourgeois as much as a Tricorn Centre would. Visually, that is. Functionally, it’s one of the world’s most prestigious business schools, and the Judge of the title is Sir Paul Judge, a Tory grandee with links to everything from The City to Nuclear Power, who once lost a libel case against the Guardian over ‘financial irregularities’. Judge funded his own list for the 2010 general election, under the umbrella of the Alliance for Democracy, along with dubious rightists like the English Democrats and Christian Voice. Judge is the Alliance’s chairman. The Judge Institute can be seen as an expression of the old kind of buccaneering, wilfully malevolent Toryism as against the soft-left soft-modernism of 1960s (and 2000s) Cambridge, hence Outram’s quasi-Thatcherite blasts against the aesthetics of ‘welfare’, building a fitting home for the managerial ‘Olympians’—but at least here all Cambridge’s contradictions are displayed rather than effaced.

Door into the Judge Institute

Across the Cam you find modern Cambridge proper, as opposed to these little irruptions. This is a land of complex gated quadrangles with only one exit, 20ft hedges, security gates, dead ends and, as we’re out of season, it’s peopled mainly by the workers who are stopping the whole thing from falling down. This other Cambridge has as its landmark Giles Gilbert Scott’s sombre skyscraping library tower, a fine example of a supposed traditionalism that actually marks off divisions rather than continuities.

There is one semi-public area, the ‘Sidgwick Site’, and it’s a fascinating battleground, a series of architectural grudge matches. At its centre is James Stirling’s notorious History Faculty, slamming together two poles of the industrial aesthetic, Manchester circa 1827 and Moscow circa 1927, showing no compromise whatsoever with its genteel setting. This is a very powerful building, if one which looks even more impressive in photos, which give no clue as to how compact and cranky it actually is, far from the dynastic monolith familiar from the architecture history books. Around it some buildings try to compete; others are more introverted. Allies and Morrison’s Criminology and English Faculties are cowardly business-park buildings cowering from Stirling, perhaps taking their cue instead from the buttoned-up courtyards of Casson and Conder’s Arts Faculty, though lacking the latter’s subtle, flowing circulation. More prepared to put up a fight is Norman Foster’s Law Faculty, which is elegant from one angle, its faceted roof running along the impeccably manicured grass, evoking Foster’s one-time mentor Buckminster Fuller, but for the most part a mere premonition of the standard Silicon Fen PFI Modernism. Far more impressive is Edward Cullinan’s Divinity Faculty, which snakes around Stirling at one point, opens out to embrace him at another, and rises into a watchtower to give it a vertical counterpoint.

Librarian’s Gotham

Stirling and Cullinan at the Sidgwick Site

Undergrowth at the Criminology Faculty

The pleasing thing about the Sidgwick Site is that you can actually walk round it if you’re a mere plebeian without feeling like you’re about to get arrested. The History Faculty is famously functionally dysfunctional. An anonymous anecdote has it that the Law Faculty was amused by the way the historians had allowed themselves to be sold a fashionable glass pup in the sixties, and mocked them for decades. Then the lawyers moved into the Foster building, which soon proved to have all of the same problems, but with few of the architectural virtues. Maybe because of this, the later buildings here take no chances. A moment of minor interest can be found in the Criminology Faculty. As a building it is drab Modernism-lite, but in its courtyard are a series of glass saucers, sticking up out of scrubland, suggesting secret things occurring underground.

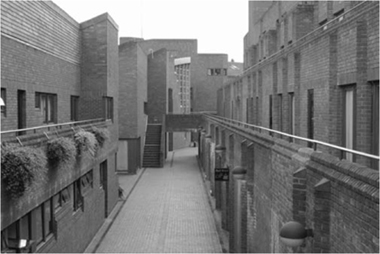

Nearby, Leslie Martin and Colin St John Wilson’s Harvey Court is the only place we actually get thrown out of, a few seconds after wandering in to catch a glimpse of its apparently ‘dynastic’ staircases—so a decision is made to sneak past the Porters’ Lodges from then on. North and west of here are the new colleges that emerged after the war, and hence more wonderful architecture and awful urbanism. The finest is surely Gillespie Kidd and Coia’s Robinson College, a wildly imaginative and spatially thrilling place that somehow manages to also be rather self-effacing. Totally nondescript when seen from the street, once inside you find something that effortlessly fuses ideas from Brutalism, the Amsterdam School, the amorphous seventies and eighties vernacular style and collegiate planning into something coherent. For all the austerity the omnipresent deep red is rich and intoxicating, as are the vistas of walkways, overhead bridges and angular extrusions. Walking round it, we can’t decide whether the red brick is, like Stirling’s, a mocking industrial challenge to Cambridge, or another example of the faux-proletarian—but here at least the effect is so powerful that objections fall by the wayside, even when we have to dodge back past the Porters’ Lodge, realizing there is no other exit. As if to inoculate against Robinson, Demetri Porphyrios’s new buildings for Selwyn College nearby are entirely Prince Charles-friendly.

Walkways at Robinson

Selwyn College, built in the twenty-first century

Meanwhile, the antipode to the tight cohesion of Robinson is Sheppard Robson’s airily expansive Churchill College, an engineering-based school, again in light-Brutalist idiom and similarly impeccably finished. It’s clearly very regularly renovated; would that the many council estates that resemble it were so well treated. At its centre is the Baroness Thatcher Archive. Fittingly, given her role in the destruction of industrial Britain, the workmanship here is poorer than in the surrounding sixties blocks, with fussy glass detailing. Like Accordia, it is wholly an estate in disguise, whose elegance, manicured lawns and regularly cleaned materials are evidence not of its superiority, but of changed priorities. When we were there, a group of Chinese teenagers, one of whom was wearing a cape, were being taught English on the green.

Learning English at Churchill College

Then there’s the New Hall, a women’s college designed as an odd mixture of boxes (some of which are new and vaguely ‘in keeping’) and domes, linked by walkways, paths and the usual utterly private courtyards. New Hall (now the Murray Edwards College, after a former student donated £30 million to it), with its curiously Islamic-looking centre, is an unexpected example of Louis Kahn-style Third Worldist modernism in a suburban corner, but it was becoming hard to enjoy the strangeness of the architecture. By this point we were sick of locked doors and getting lost in quadrangles, so Chamberlin Powell & Bon’s work here was mostly ignored by us as we tried to get out, though we noted the breeze block walls, akin to their Vanbrugh Estate for Greenwich Council, rather than to the obsessively sculpted, bristling concrete of their Barbican in the City of London.

Porte cochère at Churchill College

The watchtowers of the Mathematical Centre

The edges of Cambridge are devoted to science parks, executive housing and gated exurbia, but tasters for it exist in the city. Facing Churchill is The Crescent, neoclassical housing that, while at least more honest in its aristocratic affiliations, is hopelessly provincial, a preview for the New Town of Cambourne, which provides electronic cottages for IT professionals who can’t quite afford to live in the city itself. The blandness of these places is a reminder that the ‘two cultures’ divide works both ways, with scientists perfectly content to be utterly ignorant about architecture.

But at least one of these suburban enclaves is positively breathtaking—Edward Cullinan’s Centre for Mathematical Sciences. It’s mysterious how Cullinan and his firm managed to get a reputation as meek and mild organicists, given their propensity for obliqueness, terror and scale. The first glimpse of this Centre is of one of its sinister watchtowers peeping through the ubiquitous high hedges. Inside, we find a tangle of unnerving lookouts, walkways and roof terraces held together by obsessive symmetries, featuring a bench with the numbers ‘2000’ carved out on it, which seems futuristic for a split second until we remember the decade. We found it wholly by accident, by following the watchtowers. The eerie calm again suggests a film set rather than a place, a vision of paranoid, eccentric English technocracy which awaits its Alan J. Pakula. Here Cullinan has managed to produce some sort of summation of modern Cambridge. The gestures at vernacular, the concrete and yellow brick, are barely noticed in among its technocratic devices and an aesthetic of surveillance. It is admirable in its refusal to kowtow to the past, and dubious in the way that its many, varied and impressive spaces are only pseudo-public. More than anything else, it is an enclave—a place for the privileged to hide from the rest of the country. What exactly is Cambridge so afraid of?

The gates of English Heritage