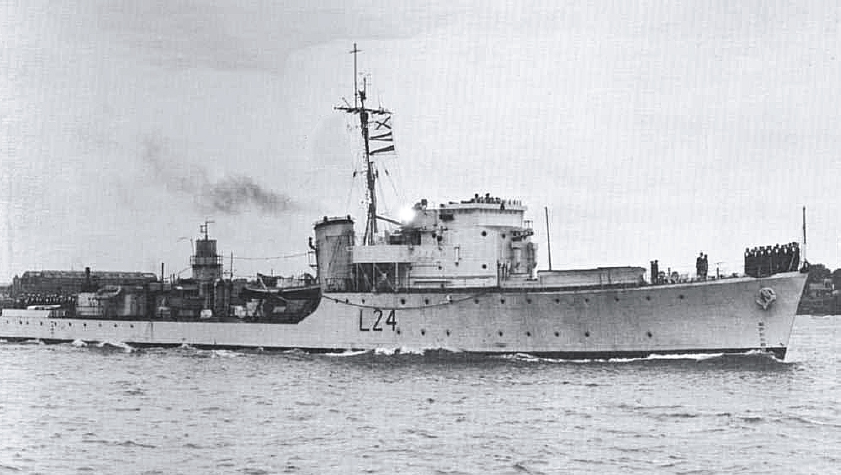

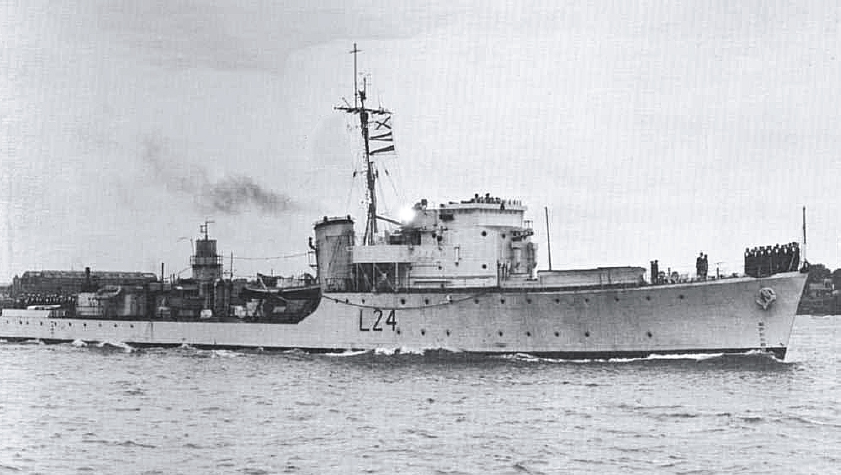

Flotilla Leader HMS Blencathra, a ‘Hunt’ class destroyer flying her pennant number, photographed without armaments late 1940.

The question in the title of this book will be familiar to many who have exchanged messages by signal lamp on shipping routes around the world. The starting point for the book was the author’s own instruction in marine signalling under Chief Petty Officer ‘Charlie’ Sewell – a boy signaller aboard HMS Neptune at the Battle of Jutland – at Pangbourne Nautical College, prior to joining P&O as a cadet. A later career as a graphic and exhibition designer, with a particular focus on our maritime heritage, has both sustained the interest and informed the research on which this book is based.

Flotilla Leader HMS Blencathra, a ‘Hunt’ class destroyer flying her pennant number, photographed without armaments late 1940.

The subject of visual communications at sea is huge, spanning, at least in written record, two and a half millennia. It is a story dominated by the development of flag signalling at sea with the early codification of signals inextricably linked with fleet manoeuvres and war fighting under sail. This is as it should be, for the imperative of commanders to communicate unambiguously with their fleets has been the driver of innovation and experiment explored here. Semaphore at sea came later and reliable signalling by light not until the end of the 19th century. All three methods are still in use and have left a legacy that has become part of our visual and cultural heritage.

From the turn of the 19th century the growing importance of the mercantile market gave rise to dozens of competing codes for communication at sea and between ships and signal stations ashore, employing flags, lights, shapes and sometimes combinations of all three. Few found wide acceptance and by mid-century the British Board of Trade, in publishing the first edition of The Commercial Code in 1857, paved the way for what would become the International Code of Signals still in use today. While not wanting to give priority here to one means of signalling over another, for each serve distinct purposes, the long history of flag signalling at sea inevitably dominates. Though reference is made to practice among other maritime nations, this book primarily reflects signalling practice in the Royal Navy and the British merchant service.

A new study of the subject must acknowledge earlier scholarship and here it is to W G Perrin and his 1922 work British Flags, their Early History and their Development at Sea that the greatest debt is owed, as it is to his 1908 study of Nelson’s famous signal at Trafalgar. Another landmark work is Signal! A History of Signalling in the Royal Navy by Captain Barrie Kent. On a lighter note, Captain Jack Broome’s 1956 Make a Signal and the later Make Another Signal celebrate the dry wit that often characterised naval signal exchanges. All are cited either in endnotes or in the bibliography. Also acknowledged at the end of the book are a number of copiously illustrated on-line resources that will fill in the gaps in this account and satisfy the most curious vexillologist.

All signalling methods had their limitations which gave rise to unintended consequences, some of which are explored here. Most signal exchanges followed the prescriptions of the Signal Book, but not all. In both Services there are anecdotal accounts of off-the-record exchanges, sometimes cryptic, nearly always good humored. A 1941 exchange of signals between a flotilla leader, Captain (D) Philip Ruck-Keene aboard HMS Blencathra (see left), and his old friend Rhoderick ‘Wee Mac’ McGrigor, Flag Captain aboard the battlecruiser HMS Renown (right) was typical of the signal sparring that relieved the tedium of routine patrols. Ruck-Keene was a man of considerable stature and his plain-language morse signal: ‘What a gigantic contraption for such a very small driver’ brought an immediate riposte from the rather shorter McGrigor: ‘While big apes cling to smaller branches’, a reference to the Royal Navy’s vital destroyer branch. McGrigor went on to become First Sea Lord.1

Radio and satellite communications have reduced the dependency on visual signalling but they are not always secure and, at close quarters, flag hoists, semaphore and light still have a role. Experimentation in the US Navy with text messaging using high-speed LED signal lamps is not something that Samuel Morse could have anticipated but, just as demands for more reliable communication in the eighteenth century drove flag design and coding methods, so do the same pressures drive experimentation in secure communication now.

As this book will show, the history of visual signalling, particularly with flags, has been a long process of iteration, with more than ten different sets of numeral flags in use between 1778 and 1900 alone. Though perhaps now more familiar on tea towels, mugs and cushion covers, many code flags still in use internationally today have their origins in the last decades of the eighteenth century. Some of the signals they have conveyed are embedded equally in our maritime heritage and popular culture, a rich legacy celebrated in these pages.

Café Press

Reinier Nooms, The Battle of Leghorn 1653 (detail). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam